Abstract

Cytochrophin-4 (cyt-4), a tetrapeptide with opioid-like activity, caused amnesia when injected into chick forebrain 5 hr after passive-avoidance training. Bilateral injections of cyt-4 directly into the lobus parolfactorius (LPO) resulted in the chicks being amnesic for the training task 24 hr later, whereas unilateral injections of cyt-4 were effective only when injected into the right LPO. Cyt-4-induced amnesia was reversed by the general opioid antagonist, naloxone, indicating that cyt-4 was acting via an opioid receptor. The μ- and δ-opioid receptors (but not κ-opioid or ORL1-receptors) have been shown to be involved in memory formation 5 hr after training (Freeman and Young 2000). Because an antagonist of the μ-opioid receptor inhibited memory, we attempted to reverse the effect of cyt-4 using μ-opioid receptor agonists. Met[enk] was unable to reverse the inhibition of memory formation by cyt-4 suggesting that the μ-opioid receptor is not involved in this effect. However endomorphin-2 (endo-2) reversed the effect of cyt-4. We further investigated the action of endo-2 using an irreversible antagonist of the μ-receptor, β-funaltrexamine (β-FAN), and found that endo-2 reversed β-FAN-induced amnesia indicating that endo-2 was not acting on the μ-opioid receptor in the chick. Because unilateral injections of β-FAN were not amnesic (bilateral injections were amnesic) this provided further evidence that the effect of cyt-4 was not mediated via the μ-opioid receptor. Coinjection of the δ-receptor agonist, (D-Pen2, L-Pen5)enkephalin (DPLPE), reversed the disruptive effect of cyt-4 on memory. However, memory modulation via the δ-opioid receptor was not lateralized to the right hemisphere suggesting that cyt-4 does not act via this receptor either. It was shown that an antagonist of the ε-opioid receptor inhibited memory at the 5 hr time point. We conclude that the ε-opioid receptor or an unidentified opioid receptor subtype could be involved in the action of cyt-4.

One-trial passive-avoidance training in the day-old chick is an attractive model to study long-term memory formation. This paradigm exploits the precocity of newly hatched chicks who explore their environment by pecking and rapidly learn to distinguish between edible and distasteful objects. If a chick is presented with a bead coated with a bitter-tasting substance such as methylanthranilate (MeA), it will peck once, show a characteristic disgust response, and subsequently avoid a similar but dry bead presented later (Cherkin 1969; Gibbs and Ng 1977). This paradigm has the advantage of requiring only a single, brief training trial, hence one can determine the time of memory induction thus allowing the sequence of events that occur during memory consolidation to be studied more easily. Using this paradigm, Freeman et al. (1995) have shown the existence of two distinct waves of protein synthesis which are involved in the laying down of long-term memory. The first occurs ⩽90 min posttraining and the other between 4 and 5 hr after training. Two phases of neuronal activity following training have also been demonstrated in the chick. Electrophysiological studies have shown a dramatic increase in spontaneous high frequency neuronal bursting in certain regions of the chick forebrain (Mason and Rose 1987). Initially, this bursting activity is distributed between left and right intermediate medial hyperstriatum ventrale (IMHV), but within 4 to 7 hr shifts to the right IMHV and to the lobus parolfactorius (LPO) (Gigg et al. 1993,1994). A series of lesion studies (Patterson et al. 1990; Gilbert et al. 1991; Patterson and Rose 1992) has shown that the IMHVs are involved in the acquisition of memory but not its retention, whereas the LPOs are involved in retention and recall but not the acquisition of memory for the passive-avoidance training. Studies using c-Fos and c-Jun as markers of neuronal activity have also demonstrated a biphasic pattern of activity, where first the IMHV is activated followed by the LPO (Freeman 1994; Freeman and Rose 1995). These findings fit in with the concept of two phases of neuronal activity with information being processed in one area of the brain (e.g., IMHV) before being redistributed to other brain regions (e.g., LPO).

Opioid peptides modulate neurotransmission by interacting with their cognate membrane receptors. There are three groups of well studied opioid receptors designated μ, δ, and κ (Kieffer 1995). In addition to the endogenous opioid peptides, a number of exogenous nonpeptide molecules known as alkaloids (or opiates) also interact with the opioid receptors and can modulate a number of biological responses. Opiates can modulate pain, analgesia, behavior and locomotor activity and affect the neuroendocrine system (Mansour et al. 1995). All three receptor classes are G protein-coupled receptors that have been shown to inhibit adenyl cyclase, decrease the conductance of voltage gated Ca2+ channels or activate K+ channel current (Childers 1991) thereby reducing membrane excitability and hence transmitter release. A number of studies suggest that there are also other classes of opioid receptors, such as the opioid-receptor-like- (ORL1), ε- and ζ-opioid receptors (Nock et al. 1990; Zagon et al. 1993). The ε-opioid receptor is a G protein-coupled receptor that acts as a neuromodulator, whereas the ζ-opioid receptor appears to affect growth but has yet to be identified in an adult brain of any species (Nock et al. 1993; Zagon et al. 1993).

Cytochrophin-4 (cyt-4) is a breakdown product of human mitochondrial cytochrome-b which has opioid-like activity (Brantl et al. 1985). As we have demonstrated previously that memory formation at 5 hr posttraining is blocked by chloramphenicol, an inhibitor of mitochondrial protein synthesis (Freeman and Young 1999), we were interested to determine whether this peptide could affect memory for passive-avoidance training at this 5 hr time point. Cyt-4 was found to inhibit passive-avoidance learning 5 hr posttraining and coinjection of naloxone, a general opioid receptor antagonist (Ward et al. 1982), showed that the effect of cyt-4 was probably opioid in character. Opioids have been shown to affect memory processing in the chick after passive-avoidance learning during both the first and second wave of neuronal activity (Patterson et al. 1989; Colombo et al. 1992,1993,1997; Freeman and Young 2000). We have attempted to identify the class of opioid receptor being targeted by cyt-4 using specific opioid receptor agonists and antagonists. As we had already shown that neither κ- nor ORL1-opioid receptors are involved in passive-avoidance learning at the 5 hr time point (Freeman and Young 2000), we have excluded these receptors as possible targets of cyt-4 and hence our investigations.

RESULTS

None of the drugs tested produced any effect on the ability of the chicks to discriminate between an aversive (chrome bead) and a nonaversive (white bead) stimulus, indicating a lack of effect on normal neuronal functioning (data not shown).

Effect of cyt-4 on Memory

Bilateral injections of 100 μm cyt-4 directly into the LPO 5 hr after training blocked long-term memory formation (Fig. 1A) (P<0.01), but when 100 μm or 300 μm cyt-4 was injected at 5 min posttraining there was no effect (Fig. 1A). The action of cyt-4 at 5 hr was shown to be lateralized to the right hemisphere, because injection of 100 μm cyt-4 only caused amnesia when injected into the right hemisphere (P<0.05) (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Effect of bilateral intracranial injections at 5 min or 5 hr after passive-avoidance training of 100 or 300 μm Cytochrophin-4. (B) Effect of unilateral intracranial injections of cyt-4 at 5 hr posttraining. Injections were 10 μl per hemisphere and made directly into the LPO. Numbers as described in text. Recall was tested at 24 hr. (*) P<0.05; (**) P<0.01.

Effect of Naloxone on cyt-4 Induced Amnesia

Amnesia due to cyt-4 (P<0.01) was reversed by the general opioid receptor antagonist naloxone (Fig. 2), indicating that the effect of cyt-4 is mediated via an opioid receptor.

Figure 2.

Effect of coinjection (10 μl per hemisphere) of cyt-4 (100 μm) and the general opioid receptor antagonist, naloxone (4 mm) into the LPO 5 hr posttraining. Numbers as described in text. Recall was tested at 24 hr. (**) P<0.01.

Effect of μ-Opioid Receptor Ligands on cyt-4-Induced Amnesia

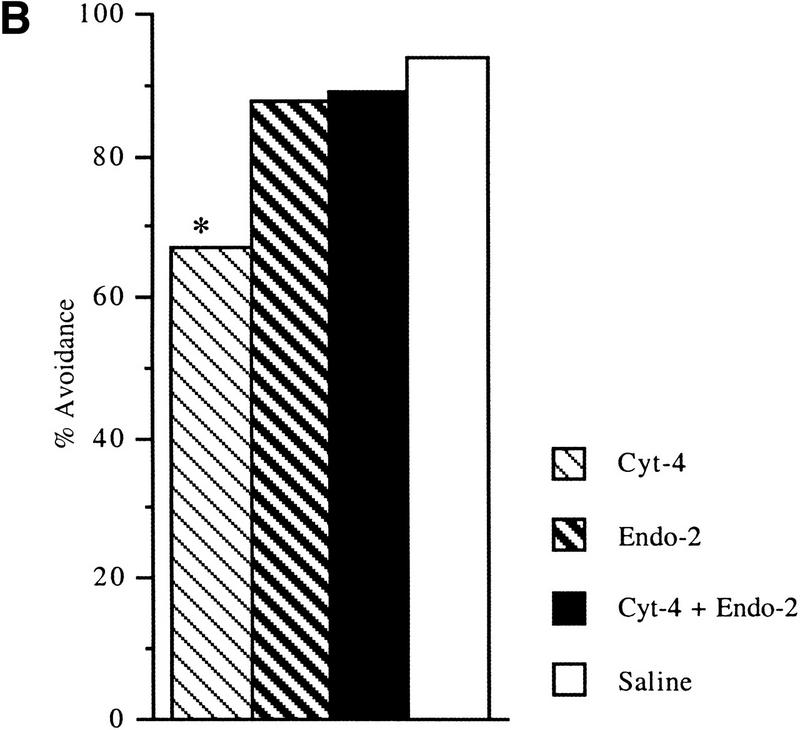

We have shown previously that inhibition of the μ-opioid receptor by β-FAN disrupted passive-avoidance learning when injected at 5 hr posttraining (Freeman and Young 2000). We therefore tested agonists of the μ-opioid receptor to see if they could reverse the effect of cyt-4. The μ-opioid receptor agonist Met[enk] did not reverse cyt-4 mediated amnesia (P<0.01) (Fig. 3A) when used at concentrations which have been shown to be effective in the chick (Columbo et al. 1997). This suggests that cyt-4 is not acting via the μ-opioid receptor. However, another putative μ-opioid receptor antagonist, endo-2, was shown to reverse the effect of cyt-4 (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Effect of coinjection of μ-opioid receptor agonists and cyt-4. (A) Cyt-4 (100 μm) and Met[Enk] (150 μm). (B) cyt-4 (100 μm) and endo-2 (100 μm). (C) Effect of coinjection of endo-2 (100 μm) and β-FAN (100 μm), μ-opioid receptor agonist and antagonist, respectively. (D) Effect of unilateral intracranial injections of β-FAN (100 μm). Injections were 10 μl per hemisphere and made directly into the LPO at 5 hr posttraining. Numbers as described in text. Recall was tested at 24 hr. (*) P<0.05; (**) P<0.01.

We were suspicious from these results that endo-2 may not be acting at the μ-opioid receptor. β-FAN is an irreversible μ-opioid receptor antagonist (Takemori et al. 1981; Ward et al. 1982) that we have shown previously to inhibit memory formation when injected at this 5 hr time point (Freeman and Young 2000). If endo-2 were acting at the μ-opioid receptor then it would be unable to reverse the memory loss due to β-FAN (or cyt-4). As Figure 3C shows, the inhibition of memory due to β-FAN was reversed by endo-2 (P<0.01), confirming our suspicions that endo-2 was not acting via the μ-opioid receptor.

Further evidence suggesting that cyt-4 is not acting via the μ-opioid receptor was obtained when unilateral injections of β-FAN are made. Unilateral injections of β-FAN did not disrupt memory formation whereas bilateral injections of β-FAN were effective in disrupting memory (P<0.01) (Fig. 3D). This is in contrast to the action of cyt-4, which was localized to the right hemisphere (Fig. 1B).

Effect of δ-Opioid Ligands on cyt-4-Induced Amnesia

There was a possible connection between cyt-4 action and the δ-opioid receptor. The δ-receptor agonist, DPLPE, was found to reverse amnesia caused by cyt-4 (P<0.01) (Fig. 4). We have shown previously(Freeman and Young 2000) that inhibition of the δ-opioid receptor by ICI-174,864 disrupted memory formation at the 5 hr time point and that this effect was reversed by DPLPE. To determine whether cyt-4 was in fact acting on the δ-opioid receptor, we unilaterally injected ICI-174,864 and found that only bilateral injections were capable of causing amnesia (P<0.01) (data not shown). Because the cyt-4 effect was localized to the right hemisphere (Fig. 1B), we believe it is unlikely that cyt-4 is acting via the δ-opioid receptor.

Figure 4.

Effect of coinjection of cyt-4 (100 μm) and DPLPE (30 μm), a δ-opioid receptor agonist. Injections were 10 μl per hemisphere and made directly into the LPO at 5 hr posttraining. Numbers as described in text. Recall was tested at 24 hr. (**) P<0.01.

Effect of ε-Opioid Receptor Ligands on Memory

As an extension of our previous research on the opioid receptors involved in memory formation at the 5 hr time point, we investigated whether the ε-opioid receptor could also modulate memory formation. Figure 5 shows that inhibition of the ε-opioid receptor by β-endorphin(1–27) disrupted memory formation when injected at 1 μm (P<0.01), demonstrating that the ε-opioid receptor is active at this time point. Higher concentrations of this antagonist were not active and the agonist β-endorphin had no effect on recall at the concentrations used. Thus it is possible that the ε-opioid receptor is involved in the action of cyt-4.

Figure 5.

Effect of bilateral intracranial injections (10 μl per hemisphere) directly into the LPO at 5 hr after training of 100, 10, and 1 μm β-endorphin(1–27) or 100, 10, and 1 μm β-endorphin. Numbers as described in text. Recall was tested at 24 hr. (**) P<0.01.

DISCUSSION

Effect of cyt-4 on Passive-Avoidance Memory

The results demonstrate that 100 μm cyt-4 inhibits memory for passive-avoidance learning when injected into the LPO at 5 hr, but not at 5 min posttraining (Fig. 1A). Unilateral injections showed that the effect of cyt-4 on memory formation at the 5 hr time point was limited to the right hemisphere (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the disruption of memory caused by cyt-4 appears to be opioid receptor-mediated as it can be reversed by coinjection of the general opioid receptor antagonist, naloxone (Ward et al. 1982; Fig. 2). Other work in this laboratory (Freeman and Young 2000) has shown that the μ- and δ-opioid receptors, but not the κ-opioid or ORL1-receptors, are involved in passive-avoidance learning at this 5 hr time point. Here we have attempted to show if cyt-4 is acting via one of the known opioid receptors.

Is cyt-4 Acting at the μ-Opioid Receptor?

Injection of β-FAN, a μ-opioid receptor antagonist, directly into the LPO was shown previously to be amnesic at 5 hr posttraining (Freeman and Young 2000). Hence it was possible that cyt-4 was acting at the μ-opioid receptor. To test this we coinjected a μ-opioid receptor agonist. The μ-opioid receptor agonist Met[enk] (Akil et al. 1984) was unable to reverse the sensitivity to cyt-4 (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the μ-opioid receptor is not involved. This inability of Met[enk] to prevent amnesia is unlikely to be caused by the use of an inappropriate concentration as Colombo et al. (1997) showed that Met[enk], at the concentration employed here, inhibited passive-avoidance memory formation when injected into the LPO around the time of training. Conversely, the putative endogenous μ-opioid receptor agonist, endo-2 (Zadina et al. 1997), did reverse cyt-4 induced amnesia (Fig. 3B). Recent studies into the action of endo-2 indicate that it may not be targeting the μ-opioid receptor in some animal species (Fischer and Undem 1999) and three observations here suggest that the effect of endo-2 may not be via the μ-opioid receptor: first, the contradictory results observed with met[enk] and endo-2;. second, the effect of β-FAN, which is an irreversible inhibitor of the μ-opioid receptor (Jiang et al. 1989), was reversed by coinjection of endo-2 (Fig. 3C); third, only bilateral injections of β-FAN were capable of causing amnesia (Fig. 3D), whereas the effect of cyt-4 was confined to the right hemisphere. We therefore conclude that cyt-4 is not mediating its action via the μ-opioid receptor.

Is cyt-4 Acting on the δ-Opioid Receptor?

Previously we have shown that the δ-opioid receptor antagonist, ICI-174,864 inhibits passive-avoidance learning when administered at this 5 hr time point and that memory disruption is prevented by coinjection of the agonist DPLPE (Freeman and Young 2000). Here we have shown that DPLPE can reverse the action of cyt-4 (Fig. 4), suggesting an involvement of the δ-opioid receptor. However, it is doubtful that the δ-receptor is the target of cyt-4 because unilateral injections of the δ-receptor antagonist, ICI-174,864 did not show any lateralization to the right hemisphere (data not shown).

Other Possible Targets of cyt-4

Nock et al. (1993) showed the existence of the ε-opioid receptor in the chick brain. They also demonstrated that it was more abundant than the μ–, δ–, or κ– opioid receptors. Studies into the ε–receptor have identified the endogenous peptide, β–endorphin as an agonist and its synthetic analog, β–endorphin(1–27) as and antagonist of the ε–opioid receptor (Tseng and Li 1986). In the chick, Patterson et al. (1989) reported that unilateral injections into the right IMHV of β-endorphin around the time of training caused amnesia. This indicates that the ε-receptor is also involved in the early stages of passive-avoidance learning. We found that inhibition of the ε-opioid receptor by β-endorphin(1–27) disrupted memory formation for passive-avoidance learning when injected into the LPO 5 hr posttraining (Fig. 5), demonstrating that the ε-opioid receptor is also active at this time point. Whether cyt-4 is targeting this receptor remains to be determined. Because we have excluded all the other classical opioid receptors at this 5 hr time point, we believe that cyt-4 is either exerting its effect via the ε-opioid receptor or via an unidentified opioid receptor subtype.

General Discussion

Our original interest in cyt-4 was as an example of an opioid-like activity that could potentially be derived from mitochondrial cytochrome-b and related to our previous observation of the specific inhibition of memory formation at the 5 hr time point by the inhibitor of mitochondrial protein synthesis, chloramphenicol. However, there appears to be no evidence at present that the generation of opioid-like peptides actually occur from mitochondrial proteins in vivo, and the relationship of such peptides to the effect of chloramphenicol on memory remains an interesting possibility.

It is interesting that the peptide sequences for cyt-4 (YPFT) and endo-2 (YPFF) differ by only one amino-acid and yet their biological effects on passive-avoidance learning appear to be opposite. However, it is not unusual for significant changes in the activity of an opiate to occur following the substitution of a single amino acid. For example, substitution of a single Leu with Met in enkephalin not only alters the peptide's affinity for δ-receptors and μ-receptors but also changes its effect on passive-avoidance memory in the chick (Columbo et al. 1997). Amnesia was only observed when leu[enk] was injected into the LPO and met[enk] into the IMHV around the time of training.

Little is known about the cascade of events that occurs during the second phase of neuronal activity, including which receptors are involved. It is therefore difficult to speculate on the possible role of opioid receptors in this process. However, at around 4 hr posttraining, the second wave of neuronal activity starts which includes protein synthesis (Freeman et al. 1995) and increased spontaneous high-frequency bursting (Gigg et al. 1994). The increase in electrical bursting in the LPO could be modulated by opioid receptors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation and Injection of Drugs

All drugs/peptides were dissolved initially in water and their salinity adjusted to 0.9% with 2 × saline. Intracranial injections of 10 μl per hemisphere were made directly into the LPO. The site and depth of delivery were controlled by the use of a specially designed stereotaxic head holder and sleeved Hamilton syringe (Davis et al. 1982). The accuracy of the injection apparatus was verified by injection of dye and subsequent microscopic analysis of tissue. β-FAN and endo-2 were purchased from Tocris; cyt-4 from Calbiochem/Nova; Naloxone, met[enk], β-endorphin(1–27), β-endorphin, and DPLPE were obtained from Sigma.

Animals and Training Procedures

White leghorn-black Australorp chicks (Gallus domesticus) of both sexes were obtained on the day of hatching. The chicks were placed in pairs in 20 × 25 × 25 cm aluminium pens, each illuminated with a 25 watt red light, and left undisturbed for 2 hr at 28–30°C before being trained on the one-trial passive-avoidance paradigm described by Lossner and Rose (1983). Briefly, birds were pretrained with three 10-sec presentations of a small (2.5 mm diameter) white bead. Chicks that pecked at least twice out of the three pretraining trials (⋝ 80%) were then trained by a 10-sec presentation of a chrome bead (4 mm diameter) dipped in MeA. Drugs or saline control were either injected at 5 min or 5 hr posttraining. The chicks were then left overnight with food and water ad libitum until 24 hr posttraining when they were tested for recall by a 20-sec presentation of a dry chrome bead and scored as Peck or Avoid. Each experiment was repeated on different days and the data pooled to remove batch-specific effects. After each test, birds were presented with a white bead similar to that used for pretraining, to test the chicks' ability to discriminate between an aversive (chrome bead) and a nonaversive (white bead) stimulus. Over 90% of the test and control chicks were able to discriminate.

Effects of cyt-4 on Passive-Avoidance Learning

To determine whether the peptide cyt-4 caused amnesia, bilateral intracranial injections of cyt-4 (10 μl per hemisphere) were made directly into the LPO at 5 min or 5 hr posttraining using concentrations of 300 μm or 100 μm with saline as control (n = 10–12). Further studies were made to see if the effect due to cyt-4 at 5 hr posttraining was lateralized by injecting 100 μm cyt-4 into either the left or right LPO, with saline injected into the contralateral LPO. Control birds received 10 μl per hemisphere of either cyt-4 or saline in both hemispheres (n = 12–14). Recall was tested at 24 hr in both experiments.

Effect of Naloxone on cyt-4-Induced Amnesia

The general opioid antagonist, naloxone, was coinjected with cyt-4 to determine whether cyt-4 was acting via an opioid receptor. Bilateral intracranial injections (10 μl per hemisphere) of 100 μm cyt-4, 4 mm naloxone (a concentration shown previously to be effective in the chick; Flood et al. 1987), cyt-4 and naloxone, or saline control were made 5 hr posttraining (n = 17–18).

Effect of μ-Opioid Receptor Ligands on cyt-4-Induced Amnesia

β-FAN, a μ-opioid receptor antagonist, has been shown previously to inhibit memory formation at this 5 hr time point (Freeman and Young 2000). If this cyt-4 sensitivity were behaving in a similar fashion, then its effects theoretically should be reversed by μ-opioid receptor agonists. Therefore, the agonist Met[enk] was coinjected with cyt-4. Bilateral intracranial injections (10 μl per hemisphere) of 100 μm cyt-4, 150 μm Met[enk], 100 μm cyt-4, and 150 μm Met[enk] or saline were made at 5 hr posttraining (n = 10).

Another putative μ-opioid receptor agonist, endo-2 was also tested to see if it could reverse cyt-4-induced amnesia. Bilateral intracranial (10 μl per hemisphere) injections of 100 μm cyt-4, 100 μm endo-2, 100 μm cyt-4 and 100 μm endo-2, or saline control were made at 5 hr posttraining (n = 16–18).

Because we were suspicious about the specificity of endo-2 towards the μ-opioid receptor, we injected chicks with 10 μl per hemisphere of 100 μm of the antagonist β-FAN, 100 μm endo-2, a solution containing both β-FAN and endo-2, or saline control (n = 17–19). If endo-2 was acting at the μ-opioid receptor it would be unable to reverse the effect of the irreversible inhibitor β-FAN.

Also if cyt-4 were acting at the same site as β-FAN (the μ-opioid receptor) then a similar pattern of lateralization for both drugs would be evident. Unilateral intracranial injections (10 μl per hemisphere) at 5 hr posttraining of 100 μm β-FAN were made into either the right or left LPO, with saline into the contralateral LPO. Control animals received either β-FAN or saline into both left and right LPO (n = 40–41).

Effect of δ-Opioid Receptor Ligands on cyt-4-Induced Amnesia

The δ-opioid receptor has been shown to be involved in passive-avoidance memory formation at 5 hr posttraining so the δ-opioid receptor agonist, (DPLPE) was coinjected with cyt-4 to see if it could reverse cyt-4-induced memory loss. Bilateral intracranial injections (10 μl per hemisphere) of 100 μm cyt-4, 30 μm DPLPE, 100 μm cyt-4 and 30 μm DPLPE, or saline were made at 5 hr posttraining (n = 20–22).

If cyt-4 were acting at the same site as DPLPE, then a similar pattern of lateralization for both drugs would be evident. To test for lateralization by the δ-opioid receptor, intracranial injections (10 μl per hemisphere) of the specific antagonist ICI-174,864 at 1 μm were made into the left or right LPO at 5 hr posttraining (n = 12).

Effect of ε-Opioid Receptor Ligands on Memory

The possible involvement of the ε-opioid receptor in passive-avoidance learning at 5 hr after training was also studied using the specific ε-opioid receptor antagonist, β-endorphin(1–27) or the agonist β-endorphin. Chicks received bilateral injections (10 μl per hemisphere) of either 100, 10, or 1 μm β-endorphin(1–27) or 100, 10, or 1 μm β-endorphin or saline as a control at 5 hr posttraining (n = 19–22).

Analysis of Data

Chicks that avoided the bead during testing were regarded as remembering the avoidance response, while those that pecked were regarded as showing amnesia. Results were expressed as the percentage of birds that exhibited recall (% avoidance) for the training task when tested at 24 hr. Comparisons of retention between drug- and vehicle-injected birds were made using χ2.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Professor S. Redman for encouragement and support.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL Ian.Young@anu.edu.au; FAX 612 6249 0415.

REFERENCES

- Akil H, Watson SJ, Young E, Lewis ME, Khachaturian H, Walker JM. Endogenous opioids: Biology and function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1984;7:223–255. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.07.030184.001255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantl V, Gramsch C, Lottspeich F, Henschen A, Jaeger KH, Herz A. Novel opioid peptides derived from mitochondrial cytochrome b: Cytochrophins. Eur J Pharmacol. 1985;111:293–294. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90773-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherkin A. Kinetics of memory consolidation. Role of amnestic treatment parameters. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1969;63:1094–1101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.63.4.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childers SR. Opioid receptor-coupled second messenger systems. Life Sci. 1991;48:1991–2003. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo PJ, Martinez JL, Bennett EL, Rosenzweig MR. Kappa opioid receptor activity modulates memory for peck-avoidance training in the 2-day-old chick. Psychopharmacol (Berl) 1992;108:235–240. doi: 10.1007/BF02245314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo PJ, Thompson KR, Martinez JL, Bennett EL, Rosenzweig MR. Dynorphin(1–13) impairs memory formation for adversive and appetitive learning in chicks. Peptides. 1993;14:1165–1170. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(93)90171-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo PJ, Rivera DT, Martinez JL, Bennett EL, Rosenzweig MR. Evidence for localized and discrete roles for enkephalins during memory formation in the chick. Behav Neurosci. 1997;11:114–122. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JL, Pico KM, Cherkin A. Memory enhancement induced in chicks by L-prolyl-L-leucine-glycineamide. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1982;17:893–896. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90467-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A, Undem BJ. Naloxone blocks endomorphin-1 but not endomorphin-2 induced inhibition of tachykinergic contractions of guinea-pig isolated bronchus. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:605–608. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood JF, Chjerkin A, Morley JE. Antagonism of endogenous opioids modulates memory processing. Brain Res. 1987;422:218–234. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman FM. Milton Keynes, UK: The Open University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman FM, Rose SPR. MK-801 blockade of Fos and Jun expression following passive avoidance training in the chick. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7:563–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman FM, Young IG. Chloramphenicol-induced amnesia for passive-avoidance training in the day-old chick. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1999;71:80–93. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1998.3867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Identification of the opioid receptors involved in passive-avoidance learning in the day-old chick during the second wave of neuronal activity. Brain Res. 2000;864:230–239. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman FM, Rose SPR, Scholey AB. Two time windows of anisomycin-induced amnesia for passive avoidance training in the day-old chick. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1995;63:291–295. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1995.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs ME, Ng KT. Psychobiology of memory: Towards a model of memory formation. Behav Rev. 1977;1:113–136. [Google Scholar]

- Gigg J, Patterson TA, Rose SPR. Training-induced increases in neuronal activity recorded from the forebrain of the day-old chick are time dependent. Neurosci. 1993;56:771–776. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90373-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Increases in neuronal bursting recorded from the chick lobus parolfactorius after training are both time-dependent and memory-specific. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:313–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DB, Patterson TA, Rose SPR. Dissociation of brain sites necessary for registration and storage of memory for a one-trial passive avoidance task in the chick. Behav Neurosci. 1991;105:553–561. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.105.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Heyman JS, Porreca F. Mu antagonist and kappa agonist properties of β-funaltrexamine (β-FAN): Long lasting spinal antinociception. NIDA Res Monogr. 1989;95:199–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer BL. Recent advances in molecular recognition and signal transduction of active peptides: Receptors for opioid peptides. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1995;15:615–635. doi: 10.1007/BF02071128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lossner B, Rose SPR. Passive avoidance training increases fucokinase activity in right forebrain tissue of day-old chicks. J Neurochem. 1983;42:1357–1363. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour A, Fox CA, Akil H, Watson SJ. Opioid-receptor mRNA expression in the rat CNS: Anatomical and functional implications. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:22–29. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93946-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason RJ, Rose SPR. Lasting changes in spontaneous multi-unit activity in the chick brain following passive avoidance training. Neurosci. 1987;21:931–944. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock B, Giordano AL, Cicero TJ, O'Connor LH. Affinity of drugs and peptides for the U-69,593-sensitive and -insensitive kappa opiate binding sites: The U-69,593-insensitive site appears to be the β-endorphin-specific epsilon receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;254:412–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock B, Giordano AL, Moore BW, Cicero TJ. Properties of the putative epsilon opioid receptor: Identification in rat, guinea pig, cow, pig, and chicken brain. J Pharmacol Expt Ther. 1993;264:349–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TA, Rose SPR. Memories in the chick: Multiple cues, distinct brain locations. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:465–470. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TA, Schulteis G, Alvarado MC, Martinez JL, Bennett EL, Rosenzweig MR, Hruby VJ. Influence of opioid peptides on learning and memory processes in the chick. Behav Neurosci. 1989;103:429–437. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.103.2.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TA, Gilbert DB, Rose SPR. Pre- and post-training lesions of the intermediate hyperstriatum ventrale and passive avoidance learning in the chick. Exp Brain Res. 1990;80:189–195. doi: 10.1007/BF00228860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemori AE, Larson DL, Portoghese PS. The irreversible narcotic antagonistic and reversible agonistic properties of the fumaramate methyl ester derivative of naltrexone. Eur J Pharmacol. 1981;70:445–451. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(81)90355-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng LF, Li CH. β-endorphin-(1–27) inhibits the spinal beta-endorphin-induced release of met-enkephalin. Int. J Pept Protein Res. 1986;27:394–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1986.tb01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SJ, Portoghese PS, Takemori AE. Pharmacological characterization in vivo of the novel opiate, β-funaltrexamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1982;220:494–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagon IS, Goodman SR, McLaughlin PJ. Zeta (zeta), the opioid growth factor receptor: Identification and characterization of binding subunits. Brain Res. 1993;605:50–56. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91355-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadina JE, Hackler L, Ge LJ, Kastin AJ. A potent and selective endogenous agonist for the μ-opiate receptor. Nature. 1997;386:499–502. doi: 10.1038/386499a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]