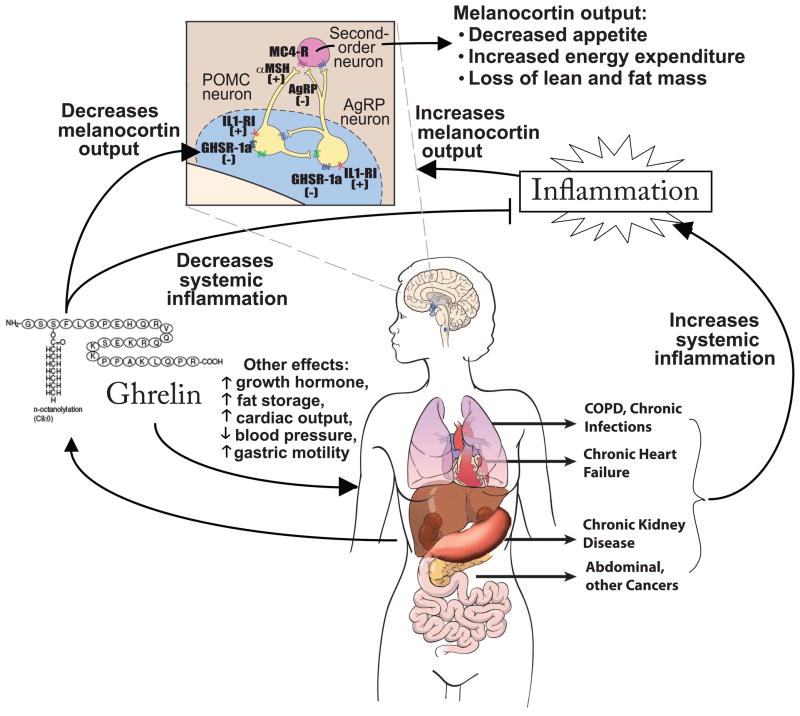

Figure 1. A model of ghrelin’s mechanisms of action in cachexia.

Cachexia in the setting of multiple different underlying etiologies appears to have in common an increase in inflammatory cytokines. This results in—among other things—effects on the central melanocortin system of the hypothalamus, a key site of ghrelin’s appetite-stimulating actions. Inflammatory cytokines act on receptors such as IL-1 receptor I (IL1-RI) to increase activity of neurons expressing pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC), increasing release of α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (αMSH), which activates the melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4-R) on downstream neurons. Inflammatory cytokines also decrease activity of neurons expressing agouti-related peptide (AgRP), a natural antagonist of the MC4-R. The net result of these processes is a decrease in appetite and increase in degradation of lean mass. Conversely, ghrelin acts on GHSR-1a to increase expression and release of AgRP and Neuropeptide Y. In addition to counter-acting the effects of inflammatory cytokines in the melanocortin system, ghrelin treatment also decreases systemic inflammation in some settings and has other potentially-important systemic effects. Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. (Adapted from DeBoer Nature Clinical Practice: Endocrinology and Metabolism 2(8):459–466 and DeBoer Nutrition 26:146–151.