Abstract

Gastrostomy (G) and gastrojejunostomy (GJ) tubes are commonly used to enhance nutrition and hydration, and facilitate the administration of medications to children with medically complex conditions. They are considered to be safe and effective interventions for the medical management of these patients; however, they are not without risks. There are common complications associated with G and GJ tubes. Health care providers play an active role in preventing, managing and supporting the patient and parents/caregivers in dealing with these complications. The present article reviews G and GJ tube devices, basic care principles, and how to prevent and manage common complications. Recommendations for how to support and share information with parents/caregivers is provided.

Keywords: Complications, Enterostomy tube, Gastrojejunostomy, Gastrostomy, Management

Abstract

Les sondes de gastrostomie (G) et de gastrojéjunostomie (GJ) sont utilisées couramment pour améliorer l’alimentation et l’hydratation et pour faciliter l’administration de médicaments aux enfants ayant des pathologies complexes. Elles sont considérées comme sécuritaires et efficaces pour la prise en charge médicale de ces patients, mais elles ne sont pas sans conséquences. Des complications fréquentes s’associent aux sondes de G et de GJ. Les dispensateurs de soins jouent un rôle actif dans la prévention, la prise en charge et le soutien du patient et des parents ou des personnes qui s’occupent de l’enfant qui affrontent ces complications. Le présent article contient une analyse des sondes de G et de GJ, des principes de soins fondamentaux et du mode de prévention et de prise en charge des complications courantes. Des recommandations sont proposées pour soutenir les parents et les personnes qui s’occupent de l’enfant et pour leur transmettre l’information.

Gastrostomy (G) and gastrojejunostomy (GJ) tube placement has become a common intervention to enhance nutrition and hydration, and facilitate the administration of medications to children with many different underlying problems (1–4). Supplementation can be complete or partial depending on the child’s ability to feed safely by mouth. Common types of diseases in children requiring long-term feeding tubes include neurological (29%) and non-neurological syndromes (18%), cancer (15%), and gastrointestinal (13%), cardiac (10%) and metabolic diseases (6%) (5). GJ tubes, which are not the preferred tubes, can be considered in certain circumstances such as when medical management for gastroesophageal reflux disease has failed and/or when the risk of aspiration of stomach contents needs to be decreased. Although feeding tubes are considered to be safe and effective, they are not without problems (1,2,4). As an example, in 2008/2009, 296 G tubes and 21 GJ tubes were inserted in the image-guided therapy (IGT) department of our hospital using the percutaneous retrograde gastrostomy (PRG) technique. During that time period, there were 932 return visits for G tube-related and 793 visits for GJ tube-related complications or maintenance issues in children who had their tube placed at our hospital at some point in the past. These very large numbers do not even include visits to primary care providers, the emergency department or the enterostomy nurse specialist. In 2004, a study published by Friedman et al (2) reported an incidence of 5% for major complications and 73% for minor complications associated with G and GJ tubes. Major complications were those that required a significant medical intervention. These included peritonitis, subcutaneous abscess, septicemia, gastrointestinal bleed and death. Minor complications were classified as those that required minimal or no intervention. These included tube dislodgement/migration, tube leakage, site infection, tube obstruction, intussusceptions and other symptoms (eg, abdominal pain or vomiting).

Our experience is primarily with enterostomy tubes placed percutaneously under fluoroscopy (PRG) (2–10); however, there is significant overlap with the complications associated with tubes placed via the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy or surgical techniques. While all techniques have a high rate of successful placement, the PRG technique is likely to have the least major complications, and the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy technique is reported to have fewer minor complications (11,12). Each technique has pros and cons, and often, decisions regarding the technique used are dictated by the experience and resources available locally. The techniques have been well described in the literature (7,13), and further detail is beyond the scope of the present article.

Primary health care providers caring for children with G and GJ tubes can play a very important role in preventing and managing complications from these tubes. The present article reviews G and GJ tube devices, basic care principles, and how to prevent and manage common complications. Recommendations on how to support and share information with parents/caregivers will be provided.

G AND GJ TUBE DEVICES

A wide variety of G and GJ tubes exist. Table 1 provides an overview of some of the most common devices used in paediatric settings, and their indications, advantages and disadvantages.

TABLE 1.

Common paediatric gastrostomy (G) and gastrojejunostomy (GJ) tube devices

| Tube | Indication | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Pigtail G tube eg, Dawson-Mueller Mac-loc pigtail (COOK Medical Inc, USA)

|

Initial G tube used in the PRG technique | Available in a variety of sizes: 8.5–14 Fr Looped (pigtail) versus balloon distal end secures tube in stomach. Balloon devices can deflate, resulting in migration |

No external anchoring device – tube must be taped to skin to prevent migration Taping of tube can cause skin breakdown and/or allergic dermatitis Smaller bore tubes can easily become blocked Tube must be replaced under fluoroscopy |

|

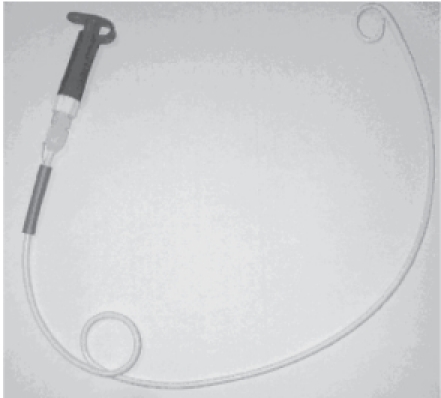

GJ tube eg, COOK GJ tube (COOK Medical Inc, USA)

|

Initial and replacement GJ tube used in the PRG technique | Gastric coil secures tube in stomach and looped (pigtail) distal end secures tube in jejunum Nonsurgical option for management of severe gastroesophageal reflux disease in children at high risk for aspiration |

No external anchoring device – tube must be taped to skin to prevent migration Distal end of tube can migrate from jejunum into stomach Taping tube to skin can cause skin breakdown and/or allergic dermatitis Smaller bore tubes can easily become blocked Tube must be replaced under fluoroscopy Looped distal end and tubes with a large bore size can increase the risk of intussusception Not available in a low-profile device |

|

PEG tube eg, MIC-PEG Feeding Tube (Kimberly-Clark Worldwide Inc, USA)

|

Initial G tube used in the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy procedure | Bulb tip secures tube in stomach and external retention ring anchors tube Bulb tip does not deflate |

Not available under 14 Fr Device can be too big and heavy for small paediatric patients External retention ring moves and loosens over time, increasing risk of migration External retention ring can make cleaning of the stoma difficult, increase moisture around stoma and result in skin breakdown, infections, enlarged stomas and granulation tissue Taping tube to skin can cause skin breakdown and/or allergic dermatitis |

|

Balloon G tube eg, MIC G tube (Kimberly-Clark Worldwide Inc, USA)

|

Replacement G tube device | Water-inflated balloon secures tube in stomach and external retention ring anchors tube Tube can be replaced by most trained health care providers and caregivers without the need for fluoroscopy or sedation |

Not available in sizes smaller than 12 Fr Device can be too big and heavy for small paediatric patients External anchoring device moves and loosens over time, increasing risk of migration External retention ring can make cleaning of the stoma difficult, increase moisture around stoma and result in skin breakdown, infections, enlarged stomas and granulation tissue Balloon device can deflate, resulting in migration and/or need for replacement Taping tube to skin can cause skin breakdown and/or allergic dermatitis |

|

Low-profile balloon G tube eg, MIC-KEY Low-Profile G tube (Kimberly-Clark Worldwide Inc, USA)

|

Replacement G tube device A measuring device determines tube length |

Water-inflated balloon secures tube in stomach Low-profile device that does not migrate easily Does not require taping to skin for anchoring Proper stoma care is easy to provide Tube can be replaced by most trained health care providers and caregivers without the need for fluoroscopy or sedation Tubes start at 12 Fr and are less likely to become blocked |

Tube length must be appropriately sized for each patient to prevent migration and skin breakdown Balloon device can deflate or break, resulting in migration and/or the need for replacement Tube bore size starts at 12 Fr and may not be an option for small paediatric patients Tube and extension sets are costly |

|

Low-profile bulb G tube eg, BARD button (BARD Inc, USA)

|

Replacement G tube device A measuring device determines tube length |

Internal bulb secures tube in stomach versus balloon Durable (1–2 years) Low-profile device that does not migrate easily Does not require taping to skin for anchoring Proper stoma care is easy to provide |

Tube must be inserted with an introducer, which is painful and increases the risk of perforation Patient may require sedation and/or fluoroscopy for the procedure, which must be performed by trained health care providers Leakage through external valve is common Tube bore size starts at 16 Fr and may not be an option for small paediatric patients Tube and extension sets are costly Tube should be replaced at 18–24 months to avoid tube breaking at the time of removal. If the internal bulb remains in the stomach, it can cause intestinal obstruction Tube is removed by direct traction, which can be painful and cause trauma to the stoma |

|

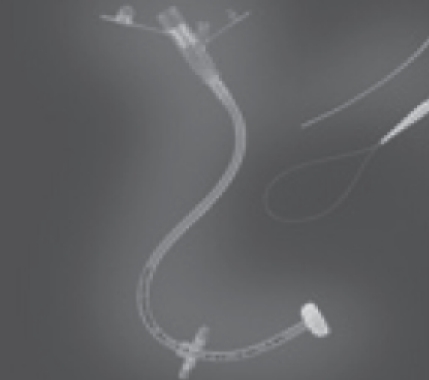

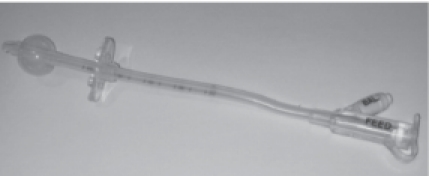

Low-profile balloon transgastric-jejunal tube eg, MIC-KEY Low Profile Transgastric-jejunal feeding tube (Kimberly-Clark Worldwide Inc, USA)

|

Replacement GJ tube with gastric outlet for venting | Nonsurgical option for management of severe gastroesophageal reflux disease Low-profile device Large bore size reduces the risk of blockage |

Tube bore size starts at 16 Fr and may not be an option for small paediatric patients Bore size can increase the risk of intussusceptions Leakage through external valve is common Tube must be replaced under fluoroscopy Tube and extension sets are costly |

PRG Percutaneous retrograde gastrostomy

PRE-TUBE INSERTION CONSIDERATIONS

There are high information needs when the option of G and GJ feeding is initially presented to parents (14). Parents need adequate and accurate information regarding the indications for long-term tube feeding, how the tube is inserted and what to expect after the tube is placed so that they can make an informed decision. For example, frequency of tube maintenance and the possible effect on quality of life may be discussed based on recent published findings (2,8). Parents need to be given the opportunity to actively engage in the decision-making process and express their opinions and concerns as information is shared with them. Other options, such as nasogastric (NG) tube feeding, may need to be considered to provide time for the parents to make their decision.

Parents are primarily responsible for the care of their children’s G or GJ tubes. Community support may be available, but can be limited and inconsistent. Education of parents is a continuous process that begins at the time of decision making and continues through to the time of discharge from hospital and while at home with their child. Preparing parents for potential complications and tube maintenance problems can help. Recognition of problems will allow for appropriate treatment options to be provided in a timely manner (13). Table 2 provides a detailed list outlining timing of information and training that should be provided to parents.

TABLE 2.

Information and training that should be provided to parents at specific times

| Decision-making period | Pre-tube insertion | Post-tube insertion |

|---|---|---|

| Describe indications for gastrostomy versus gastrojejunostomy tube insertion Describe complete versus supplemental nutrition support Describe benefits and limitations of tube feeding Provide information on nasogastric tube feeding as a short-term option while decision is being made or while waiting for tube to be inserted Describe procedure for tube insertion, its complications and expected course in hospital Identify that a patient with underlying anatomical issues, such as scoliosis or hepatosplenomegaly, may present with technical challenges during the time of insertion Identify patients at risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease and aspiration |

Prepare patient for procedure and admission to hospital (detailed description of procedure, pre- and postinsertion preparation and expected outcomes) Obtain consent for procedure Describe care of patient with tube in situ: stoma, tube and equipment Identify potential complications, how to prevent and treat Identify enterostomy resources in hospital and community. Contact community nursing agency (if already involved) Develop feeding plan: oral and/or tube feeding schedule: what formula, how much and when Identify medications patient is taking and how to administer through tube Contact insurance provider and government support programs to determine options for payment of equipment, supplies and formula |

Teach monitoring for immediate and long-term complications Practice:

Review plan of care with the following:

|

POST-TUBE INSERTION CONSIDERATIONS

In hospital

Monitor the patient closely for signs and symptoms of postprocedural complications and discomfort (eg, abnormal vital signs, irritability, bleeding from the stoma, emesis and signs of peritonitis). Maintaining good analgesia immediately following tube insertion (eg, morphine) and up to four days after insertion (eg, acetaminophen) is important. The use of local Xylocaine (AstraZeneca Canada Inc, Canada) at the time of the procedure can help with immediate postprocedural pain. Feeding through the new tube is initiated when bowel sounds return – usually approximately 12 h following tube insertion. An NG tube is placed to ensure drainage of the stomach until gastric motility has returned. An electrolyte solution is initially given and then, depending on the patient’s tolerance, is advanced to formula. Patients are advised not to eat by mouth until they have reached their full tube feeding requirements because of concerns regarding overfilling the stomach, which could cause retching, vomiting, dislodgement of the new tube and/or peritonitis. It is important to ensure that the patient’s essential medications (eg, anticonvulsant therapy) are continued either through the intravenous, NG or new enterostomy tube.

Skin care

Our particular protocol includes leaving the initial procedure dressing in place for 24 h. The tube must be well anchored to the skin. The dressing is then changed twice daily for three days and then once a day for 14 days after the initial date of tube insertion. The stoma is cleaned with a mild soap and water. The dressing is clean but not sterile. It consists of a piece of 2×2 gauze, with a Y cut into the centre to allow the gauze to sit around the tube. The tube must then be anchored to the skin to prevent migration and damage to the tube. Figure 1 demonstrates proper anchoring of the tube. We suggest that the tube be rotated and anchored in a different location daily (1). Moving clockwise in one-quarter increments is a helpful guideline.

Figure 1).

Image of proper anchoring of a tube

After 14 days, the dressing is no longer required. The retention suture (which is used in the PRG technique to secure the stomach to the anterior abdominal wall) is removed by cutting the suture (thread) from the point it exits the stoma, at which point, the patient can bathe again. The stoma continues to be cleaned with soap and water daily. The use of alcohol or hydrogen peroxide-based products is not recommended because they may cause skin irritation. Keeping the stoma dry helps prevent infection and skin breakdown; therefore, antimicrobial creams, ointments and dressings are not recommended (1). Figure 2 illustrates an ideal stoma.

Figure 2).

Image of a normal stoma

Activities of daily living

Children with G or GJ tubes should not be limited in their activities of daily living by their feeding tube. Feeding schedules should fit the child and family’s life at home and in the community. The feeding tube should not interfere with participation in daily activities (eg, physiotherapy, sports, school and recreational activities). Children can swim with the tube. Children who can safely eat by mouth should be encouraged to do so. They should be included in mealtimes at home and at school. Nutritional supplementation should be provided after oral feeding. Children who cannot safely eat by mouth or who have an oral aversion will need ongoing therapy. These assessments can be performed by a feeding team, occupational therapist or speech-language pathologist, either clinically or radiologically, as indicated.

Tube replacement

G and GJ tubes should not be replaced until the gastrocutaneous tract has been well established (1). At The Hospital for Sick Children, we do not replace them until at least eight weeks after the initial tube insertion. Risks associated with early tube replacement include tube migration and perforation through the tract into the peritoneal cavity, and gastric leakage into the peritoneal cavity during the process of tube replacement, resulting in peritonitis. Once the tract is mature, elective tube changes should be safe (1). Parents should still be informed of the risk of perforation, and the signs and symptoms of peritonitis. Parents and children should be given the option of having the initial G or GJ tube changed to a low-profile device (Table 1). Low-profile GJ tubes may not be an option in most paediatric patients because they are not available in small bore sizes (ie, smaller than 16 Fr). These devices have numerous advantages compared with pigtail and other high-profile devices. If properly fitted, they reduce migration, promote proper cleaning of the stoma and eliminate the need for taping the tube to the skin. Many health care providers, parents and children themselves can be trained to replace most balloon-filled G tubes. Certain tubes, such as the COOK G and GJ tubes (COOK Medical Inc, USA), must be replaced using fluoroscopy. The common practice is to replace tubes routinely at eight to 12 months or with any signs of tube breakdown to avoid emergent tube changes.

COMPLICATIONS

Table 3 provides an overview of common complications, their causes and suggested management strategies.

TABLE 3.

Common complications associated with gastrostomy (G) and gastrojejunostomy (GJ) tubes

| Complication/presentation | Possible causes | Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Tube migration | ||

| G tube has moved past pyloric sphincter, patient may not tolerate feeds, there may be retching or vomiting with or without feeding. It can cause dumping syndrome or hypoglycemia The GJ tube tip can flip back into stomach – patient usually presents with vomiting of formula/feeding intolerance |

Tube is not adequately secured to skin Gastrointestinal peristalsis |

For G tube:

For GJ tube:

|

| Site infection (Figure 3) or subcutaneous abscess | ||

| Common signs/symptoms: Tenderness (often is the first sign; sometimes is not recognized, particularly in the neurologically impaired patient) Redness Swelling Increased purulent and/or foul-smelling discharge Fever Pustule formation adjacent to stoma Pinpoint rash, may indicate fungal infection Note: a small amount of crusty yellow/green discharge from stoma is normal (15) |

Poor site care, and dressing in place for prolonged periods of time Bacterial infections often caused by Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas species, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter cloacae, Streptococcus, Lactobacillus and Bacteroides species (15) Fungal infections are common, particularly if area is moist and/or the patient has oral thrush or candidal diaper dermatitis Low-profile tubes that are too small/tight can cause stoma/skin breakdown and infection |

Clean site daily with soap and water or during bathing Warm saline compresses. Take a piece of 2×2 gauze with a Y-shaped cut. Soak gauze with warm (not hot) normal saline. Place gauze around site and compress for 3–5 min. Repeat 2–3 times. Dry site well with gauze, a clean washcloth or let it air dry. Repeat 3–4 times daily. Topical antibiotic creams (such as Polysporin [Johnson & Johnson Inc, Canada], Bactroban [GlaxoSmithKline Inc, Canada] or Fucidin [Leo Pharma Inc, Canada]) applied to site (not recommended for more than 5–7 days) If redness continues to spread beyond site, or there are signs of systemic toxicity (eg, fever), an oral antibiotic, such as Keflex (MM Therapeutics Inc, Canada) or clindamycin, may need to be considered For fungal infections, treat with mixture of hydrocortisone/nystatin cream Remove all dressings Treat any granulation tissue Ultrasound may be necessary to diagnose a subcutaneous abscess Consider sending a culture of any purulent discharge |

| Granulation tissue (Figure 4) | ||

| Overgrowth of tissue around the stoma Often pink, ‘cauliflower-like’ appearance, moist and bleeds easily |

Excessive movement of tube, or trauma to site Dressing over stoma Low-profile tube is inappropriately sized (too long or short) |

Ensure tube is secured to skin Remove dressing Apply warm saline compresses 3–4 times daily If saline compresses are not effective and tissue is large, moist and friable, consider applying silver nitrate every 2–3 days until it resolves. Protect surrounding skin with a barrier cream before applying silver nitrate to avoid burning normal skin (1,15) For balloon devices, ensure balloon is intact and appropriately inflated |

| Leakage and enlarged stoma (Figure 5) | ||

| Excessive leakage of acidic gastric contents from stoma causing skin breakdown and enlargement of stoma Gastric leakage can cause contact dermatitis (Figure 6) |

Excessive movement of tube Accumulation of granulation tissue Poor motility, constipation, chronic cough or vomiting Cracked tube |

Tape tube securely to abdomen Do not insert a tube with a larger bore size (it will further enlarge the stoma) If child has poor motility, may benefit from motility agent, laxative Consider high-dose proton pump inhibitors to decrease acidity of leaking contents Check balloon regularly (every week) for recommended amount of water, and fill as required Pull back on tube gently until resistance is felt to ensure internal securing device is flush to stomach wall. Do not pull tube too tight If there is skin breakdown from leakage, use a barrier cream (eg, Proshield [Healthpoint Canada ULC, Canada], petroleum jelly or zinc oxide) For contact dermatitis, consider spraying affected area with Flonase (GlaxoSmithKline Inc, Canada) Foam dressings such as Allevyn (Smith & Nephew, United Kingdom) adhesive dressing can be considered but must be replaced frequently Consider removing tube for a short period of time to promote constriction of tract. A small bore Foley catheter can be inserted to ensure tract does not close (15). Patient may need to be fed by GJ tube or fed nothing by mouth (admission to hospital for total parenteral nutrition) to decrease gastric leakage and promote healing of enlarged stoma |

| Obstructed tube | ||

| Cannot instill formula or medications through tube | Inadequate flushing Inadequate dissolving of medications Administering medication that is known to block the tube such as the following:

|

Flush tube with warm tap water before and after administering formula and medications (volume of the flush will depend on size of child and any fluid restriction) For children receiving a continuous feed, tube should be flushed every 4–6 h Use liquid form of medications when possible Do not crush medications that are sustained released, enteric coated or microencapsulated (16) Dissolve any tablet medications completely, administer immediately followed by a water flush Caution and extra flushes should be used when administering medications that can be given by tube but are known to block easily such as the following:

Blocked tubes: flush with carbonated water using a 1–3 mL syringe. Gently push or pull on the syringe to attempt to clear the blockage Pancreatic enzymes are used in some institutions Tube may need replacement (1,15,16). When waiting for GJ tubes to be replaced under fluoroscopy, consider alternate methods for providing hydration and medications (could include intravenous, nasogastric or removal of GJ tube and replacement with Foley catheter). Administration through a nasogastric tube or Foley catheter should only be considered in patients with a history of tolerating small volumes of fluids in the stomach Pressure from trying to unblock tube can cause tube breakdown and will need replacement |

| Tube dislodgement | ||

| Tube is out of tract | Tube is not anchored in place Balloon has deflated Tube is damaged or defective |

Secure tube to abdominal wall at all times, not on diaper or clothing Consider dressing patients with undershirts, put sleepers on back to front or overalls to make it difficult to grab tube G and GJ tubes that have been in place for 8 weeks or less from initial date of insertion are considered to have immature tracts and should have a Foley catheter inserted into the tract to prevent closure of the stoma. The Foley catheter should be one size smaller than the patient’s initial tube. The balloon should not be inflated with water and the Foley catheter should not be used for feeding. The permanent tube should be replaced by the health care provider and placement must be confirmed G tubes that have been in place for more than 8 weeks can be replaced with a balloon device or Foley catheter that is the same size as the initial tube. The balloon can be inflated and the tube can be used after placement is confirmed by aspirating gastric contents from the new tube. Consider checking tube placement under fluoroscopy if replacement was difficult or if positioning is questionable GJ tubes should always be replaced under fluoroscopy, but a Foley catheter can be inserted to prevent the tract from closing |

| Intussusception | ||

| Intestinal obstruction at the site of the GJ tip (9,17–19) | Small size of patient Large bore size of tube Pigtail end of tube Intestinal motility |

Insert a smaller bore GJ tube Radiologist can cut off pigtail Shorten length of GJ tube Consider returning to gastric feeding Consider surgical option (ie, Nissen fundoplication) |

References are provided in parentheses where applicable

CONCLUSION

Feeding tubes in paediatric patients can be very helpful in allowing the child to achieve an appropriate nutritional status, which in turn, can have a positive effect on their disease management and control. Nevertheless, health care providers must be very aware of the many potential tube maintenance issues and complications so they can attempt to prevent and treat them appropriately when they inevitably occur.

Figure 3).

Image of an infected stoma

Figure 4).

Image of granulation tissue

Figure 5).

Image of an enlarged stoma

Figure 6).

Image of contact dermatitis

REFERENCES

- 1.Burd A, Burd RS. The who, what, why, and how-to guide for gastrostomy tube placement in infants. Adv Neonatal Care. 2003;3:197–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman JN, Ahmed S, Connolly S, Chait P, Mahant S. Complications associated with image guided gastrostomy and gastrojejunostomy tubes in Children. Pediatrics. 2004;114:458–61. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korczak DJ, Connolly B, Baron T, Katzman DK, Bernstein S. Experience with image-guided gastrostomy and gastrojejunostomy tubes in children and adolescents with primary psychiatric illnesses. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:645–51. doi: 10.1002/eat.20404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis EC, Connolly B, Temple M, et al. Growth outcomes and complications after radiologic gastrostomy in 120 children. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:963–70. doi: 10.1007/s00247-008-0925-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearce CB, Duncan HD. Enteral feeding. Nasogastric, nasojejunal, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, or jejunostomy: Its indications and limitations. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:198–204. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.918.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aziz D, Chait P, Kreichman F, Langer JC. Image-guided percutaneous gastrostomy in neonates with esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1648–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chait PG, Weinberg J, Connolly BL, et al. Retrograde percutaneous gastrostomy and gastrojejunostomy in 505 children: A 4 1/2-year experience. Radiology. 1996;201:691–5. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.3.8939217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahant S, Friedman JN, Connolly B, Goia C, Macarthur C. Tube feeding and quality of life in children with severe neurological impairment. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:668–73. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.149542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg J, Amaral JG, Sklar CM, et al. Gastrostomy and gastrojejunostomy placements: Outcomes in children with gastroschisis, omphalocele, and congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Radiology. 2008;248:247–53. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2481061193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sy K, Dipchand A, Atenafu E, et al. Safety and effectiveness of radiological percutaneous gastrostomy and gastrojejunostomy in children with cardiac disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:1169–74. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maclean AA, Alvarez NR, Davies JD, Lopez PP, Pizano LR. Complications of percutaneous endoscopic and fluoroscopic gastrostomy tubes insertion procedures in 378 patients. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2007;30:337–41. doi: 10.1097/01.SGA.0000296252.70834.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neeff M, Crowder VL, McIvor NP, Chaplin JM, Morton RP. Comparison of the use of endoscopic and radiologic gastrostomy in a single head and neck cancer unit. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:590–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.t01-1-02695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glader L, Palfrey JS. Care of the child assisted by technology. Pediatr Rev. 2009;30:439–44. doi: 10.1542/pir.30-11-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerriere DN, McKeever P, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Berall G. Mothers’ decisions about gastrostomy tube insertion in children: Factors contributing to uncertainty. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45:470–6. doi: 10.1017/s0012162203000872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg E, Kaye R, Yaworski J, Liacouras C. Gastrostomy tubes. Facts, fallacies, fistulas, and false tracts. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2005;28:485–93. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200511000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beckwith MF, Feddema SS, Barton RG, Graves C. A guide to drug therapy in patients with enteral feeding tubes: Dosage form selection and administration methods. Hosp Pharm. 2004;39:225–37. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Connolly BL, Chait PG, Siva-Nandan R, Duncan D, Peer M. Recognition of intussusception around gastrojejunostomy tubes in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;17:467–70. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.2.9456966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes UM, Connolly BL, Chait PG, Muraca S. Futher report of small bowel intussusceptions related to gastrojejunostomy tubes. Pediatr Radiol. 2000;30:614–7. doi: 10.1007/s002470000260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hui GC, Gerstle JT, Weinstein M, Connolly B. Small bowel intussusception around a gastrojejunostomy tube resulting in ischemic necrosis of the intestine. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:916–8. doi: 10.1007/s00247-004-1230-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]