Abstract

Background

Several studies have indicated that endotoxemia is the required co-factor for alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) that is seen in only about 30% of alcoholics. Recent studies have shown that gut leakiness that occurs in a subset of alcoholics is the primary cause of endotoxemia in ASH. The reasons for this differential susceptibility are not known. Since disruption of circadian rhythms occurs in some alcoholics and circadian genes control the expression of several genes that are involved in regulation of intestinal permeability, we hypothesized that alcohol induces intestinal hyperpermeability by stimulating expression of circadian clock gene proteins in the intestinal epithelial cells.

Methods

We used Caco-2 monolayers grown on culture inserts as an in vitro model of intestinal permeability and performed western blotting, permeability, and siRNA inhibition studies to examine the role of Clock and Per2 circadian genes in alcohol-induced hyperpermeability. We also measured PER2 protein levels in intestinal mucosa of alcohol fed rats with intestinal hyperpermeability.

Results

Alcohol, as low as 0.2%, induced time dependent increases in both Caco-2 cell monolayer permeability and in CLOCK and PER2 proteins. SiRNA specific inhibition of either Clock or Per2 significantly inhibited alcohol-induced monolayer hyperpermeability. Alcohol-fed rats with increased total gut permeability, assessed by urinary sucralose, also had significantly higher levels of PER2 protein in their duodenum and proximal colon than control rats.

Conclusions

Our studies: (1) demonstrate a novel mechanism for alcohol-induced intestinal hyperpermeability through stimulation of intestinal circadian clock gene expression, and (2) provide direct evidence for a central role of circadian genes in regulation of intestinal permeability.

Keywords: ethanol, intestinal permeability, Clock gene, Per2 gene, Circadian rhythm

Introduction

Several epidemiological studies have shown that alcoholism causes tissue injury such as alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) in only about 30% of alcoholics (Grant et al., 1988; Rao et al., 2004). These data indicate that chronic alcohol (EtOH) consumption is a required but not a sufficient factor for ASH. Although the reasons behind this differential susceptibility are not fully understood, multiple clinical and experimental studies have provided compelling evidence that gut derived endotoxin is directly involved in the initiation of sustained necroinflammatory cascades in the liver that are required for alcohol-induced tissue injury, including ASH (Rao et al., 2004; Purohit et al., 2008). A major challenge is to determine the factors that are responsible for the development of gut leakiness and endotoxemia in only a sub-set of alcoholics (or conversely, factors that may protect alcoholics from gut leakiness).

We wished to test the hypothesis that disrupted circadian rhythms may contribute to the differential susceptibility for alcohol-induced gut leakiness in a subset of alcoholics. Our rationale for this hypothesis and the key findings linking circadian rhythms, alcohol, and the gut, are: (1) The core circadian clock molecular machinery is within essentially all the tissues and organs of the body including the central circadian clock in the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), and intestinal epithelial cells (Hastings et al., 2003; Yoo et al., 2004; Bell-Pedersen et al., 2005; Hoogerwerf et al., 2007); (2) The SCN regulates and coordinates the expression and timing of multiple peripheral circadian molecular rhythms (Green et al., 2008; Laposky et al., 2008a), possibly including brain-gut interactions of the so called “brain-gut axis,” (BGA); (3) The BGA can regulate intestinal permeability, and disruption of this communication by pathological stimuli like physical and psychological stress that can affect circadian rhythms can also cause gut leakiness in both humans and rodents (Gareau et al., 2007; Stasi and Orlandelli, 2008); (4) The circadian modulation of the brain-gut communication could mediate normal and pathological states of intestinal permeability since circadian genes can regulate apical junctional complex (AJC) protein genes that are directly involved in regulation of intestinal permeability (Yamato et al., 2010); (5) Alcohol can disrupt the central SCN circadian rhythm in rodents and affect expression of clock genes in the brain and these effects may be different in a subset of alcoholics (Mistlberger and Nadeau, 1992; Chen et al., 2004; Rosenwasser et al., 2005b; Rosenwasser et al., 2005a; Spanagel et al., 2005a; McElroy et al., 2009; Seggio et al., 2009); (6) The Clock gene is important for the circadian regulation of macronutrient absorption by enterocytes in the gut (Pan and Hussain, 2009).

Although these data provide compelling evidence to suggest a role of disrupted circadian rhythms in the etiology of alcohol-induced gut leakiness, there is no direct evidence for a role of the circadian molecular machinery in alcohol-induced intestinal hyperpermeability. Therefore, we carried out studies in a validated in vitro model of intestinal permeability (Caco-2 cell monolayers) as well as on intestinal tissue from an in vivo rodent alcohol model of leaky gut to directly test the hypothesis that the circadian clock molecular machinery can directly impact alcohol-induced gut leakiness. Our overall objective was to determine whether alcohol can impact circadian clock gene expression in intestinal epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo and also to determine whether modulation of intestinal circadian genes in vitro can impact the effects of alcohol on intestinal permeability.

Materials and Methods

Intestinal epithelial cell monolayer barrier function

Barrier permeability was determined using Caco-2 cells grown to confluence on Type 1 collagen-coated 12 mm/0.4μm PET tissue culture plate inserts (Transwell, Corning, Corning, NY) as we previously described (Banan et al., 1999; Banan et al., 2000; Forsyth et al., 2007). Permeability of insert Caco-2 monolayers was measured as apical to basolateral flux of the fluorescent marker fluorescein-5-(and-6)-sulfonic acid trisodium salt (FSA, 478 d) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or as Transepithelial Electrical Resistance (TER). TER is determined using a dual electrode system designed for cell culture insert analysis (EVOM, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). Cell viability is routinely measured by live/dead assay (Invitrogen) or trypan blue staining. Cell viability for all assays was greater than 95%. We have also previously shown that alcohol in concentrations as high as 1% has no effect on Caco-2 viability in this assay for as long as 6h (Banan et al., 1999; Banan et al., 2000).

Treatment of cells with siRNA

Caco-2 cells were treated with siRNA using a modification of our previously published methods (Forsyth et al., 2010). Briefly, 105 cells are combined with 11 picomoles of siRNA in 50μl Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) and 50μl Optimem (Invitrogen), mixed by gently shaking and then plated on Type 1 collagen coated Corning 12mm PET culture inserts (#3460) (Corning). Inserts are used for permeability studies 72-96h after plating, when cells are confluent. Clock and Per2 siRNA was On Target Smartpool from Dharmacon (Dharmacon Inc., Lafayette, CO). The siRNA sequences for Clock (cat.# L-012977-00) were: CAACUUGCACCUAUAAAUA; CGACAGGACUGGAAACCUA; GAACAACGGACACGCAUGA; CUAGAAAGAUGGACAAAUC; the siRNA sequences for Per2 (cat.# L-08212-00) were: GAAUGGAUACGCGGAAUUU; CUUCAGCGAUGCCAAGUUU; GCAGUGGAGCAGAUUCUUU; CGACCAGUCUUCGAAAGUG while control (non-targeting) siRNA was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and the sequence is proprietary (cat.# 37007). Figure 1 shows that as a further control for off target effects of siRNA treatment in addition to the use of nontargeting siRNA as a control, we performed western blot analysis for CLOCK protein expression in lysates from the Per2 knockdown experiments shown in Fig. 5. As seen in Fig. 1, Per2 siRNA did not significantly affect CLOCK protein levels compared to our average of 70% knockdown of PER2 protein with the Per2 siRNA (see Fig. 5), thus supporting that the specific effect of the Per2 siRNA on Caco-2 permeability was not due to effects on CLOCK protein expression but were in fact due specifically to Per2 expression knockdown with siRNA.

Fig. 1.

Densitometry data for western blot of CLOCK protein in Per2 siRNA knockdown experiment. As a further control for off target effects of siRNA treatment we performed western blot analysis for CLOCK protein expression in lysates from the Per2 knockdown experiments shown in Fig. 5. Per2 siRNA did not significantly affect CLOCK protein levels compared to our average of 70% knockdown of PER2 protein with the Per2 siRNA and supporting that the specific effect of the Per2 siRNA was not due to effects on CLOCK protein expression but were in fact due to Per2 knockdown.

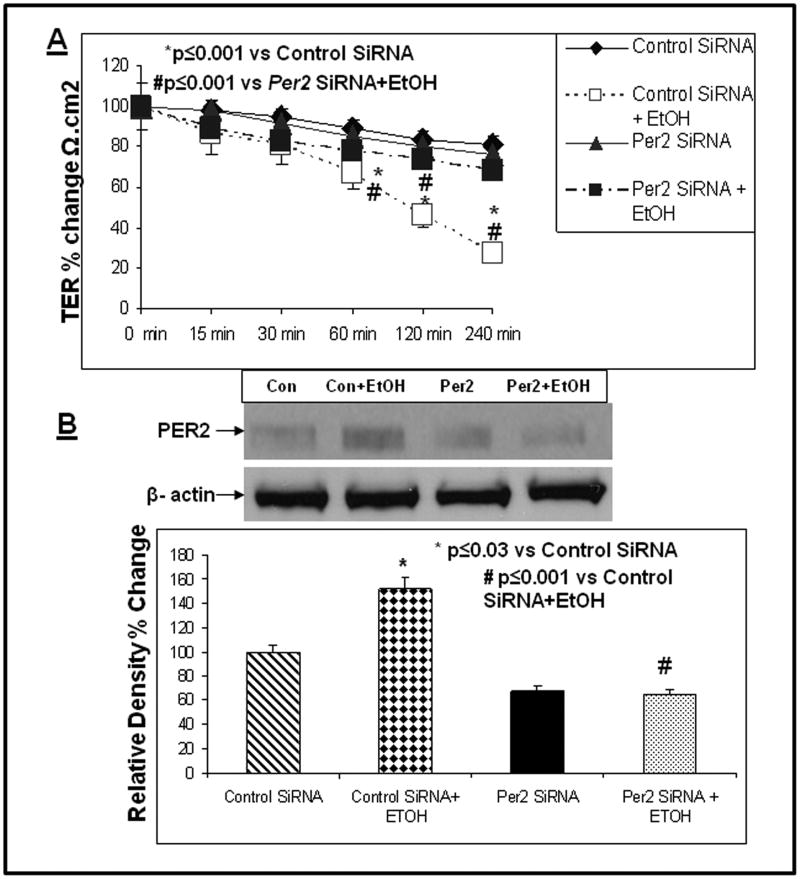

Fig. 5.

SiRNA inhibition of PER2 protein expression prevents alcohol-induced hyperpermeability of Caco-2 monolayers. To assess the role of alcohol-stimulation of PER2 protein expression in the alcohol-induced increased permeability of Caco-2 monolayers, we inhibited PER2 protein expression with siRNA specific for Per2 and compared the effects to cells also treated with alcohol but treated with control siRNA. Fig. 5A (upper panel) depicts permeability data which are presented as % Change TER (Ω/cm2). TER data are presented as % change versus the “0” time point control for each condition. Data are means from triplicate wells in 3 experiments (total N=9) for each time point ± SE. *p≤0.001 vs. Control siRNA; #p≤0.001 vs. Per2 siRNA+ EtOH Fig. 5B middle panel shows data from lysates from 4 representative inserts for each treatment group confirming that cells treated with Per2 siRNA expressed significantly lower levels of PER2 protein. Figure 5B lower histogram shows the summarized densitometry data for all western blots (N=9 inserts each group, each time point) confirming knockdown of PER2 protein by about 70% in Per2 siRNA and alcohol-treated cells compared to alcohol-treated control siRNA cells. Data are expressed as % Relative Density ± SE versus the control siRNA treated cells not treated with alcohol (set as 100%). * p≤0.03 vs. Control siRNA; # p≤0.001 vs. Control siRNA+ EtOH. Fig. 5C depicts FSA permeability data expressed as % change FSA flux vs. control siRNA treated cells for permeability of Caco-2 cells treated as in Fig. 5A above. All permeability data are means ± SE from triplicate wells in 3 experiments (9 data points). *p≤ .05 vs. control siRNA treated cells + EtOH.

Animal model of alcohol-induced gut leakiness

We have recently published a Rush IACUC animal use committee approved rat model of alcohol-induced gut leakiness (Keshavarzian et al., 2009). In brief, male Sprague-Dawley rats (250-300 g at intake) were obtained from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN). During experiments, each rat was given either alcohol or an isocaloric amount of dextrose in liquid rat chow intragastrically (by gavage; 2 cc) 2× daily. Intestinal permeability was measured twice: (i) just prior to alcohol administration; and (ii) just before sacrifice. Rats were sacrificed after 2, 4, 8, and 10 weeks of administration of 6 g/kg/day alcohol with N=6 or greater for each time point.

Intestinal permeability in rats

Sprague-Dawley rats (6-8wk, 250-300g) were maintained in a metabolic cage (for 6 hour urine collection) and gut permeability is measured for each rat after a sugar bolus by gavage as we previously described (Farhadi et al., 2006; Keshavarzian et al., 2009). Measurement of urinary sugars using GC is used to calculate intestinal permeability and is expressed as percent oral dose excreted in the urine. We have recently revised our method which briefly involves conversion of the relevant sugars to their alditol acetate form rather than our previous method of N-Trimethylsilylimidazole (TMSI) derivatization and find it is a more sensitive method to detect the sugars. This is thus a modification of our method that we previously published (Farhadi et al., 2006; Keshavarzian et al., 2009). The widely used urinary L/M (L = lactulose, M=mannitol) ratio represents only small bowel permeability, while the urinary sucralose excretion reported in this study represents total intestinal permeability [small bowel +colonic permeability].

Measurement of clock genes protein expression

Circadian clock genes (Per2, Clock) protein levels were assayed by western blot. Western blotting and densitometry analysis with Image J software (NIH) was performed with cell or tissue lysates equalized for total protein and cell number as previously described (Forsyth et al., 2002; Forsyth et al., 2007). CLOCK Ab was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and PER2 Ab was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) while anti-actin Ab was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Data Analysis and Statistics

The data are presented as means ± SE. For circadian genes protein levels, group means were compared by ANOVA and post-hoc tests since the data were normally distributed. For permeability data in rats, group means were compared using the nonparametric analyses, Kruskal-Wallis test, because data were not normally distributed. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were done using SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Alcohol at Physiological Concentrations Increases Permeability of Caco-2 Intestinal Epithelial Cell Monolayers

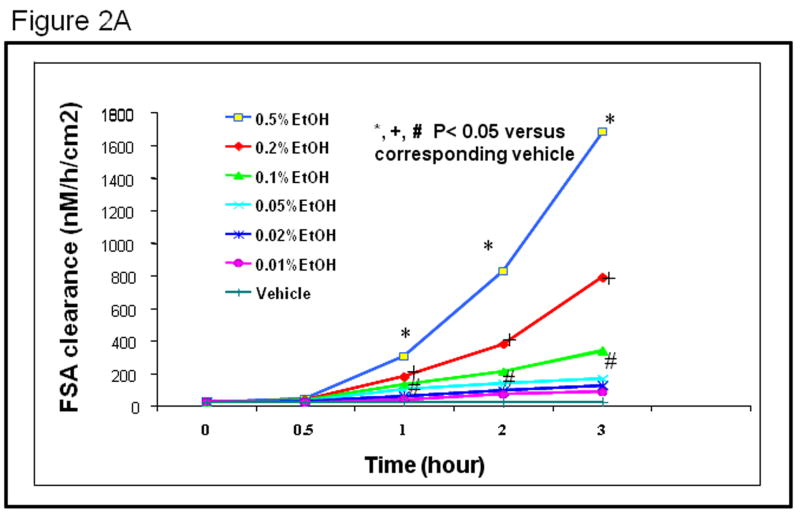

We have previously shown that alcohol at concentrations of 1-15% increases permeability of Caco-2 cell monolayers, the most widely used in vitro model of intestinal permeability(Banan et al., 1999; Banan et al., 2000). We now wished to test alcohol concentrations more relevant to those found in the mucosal layers of the distal intestine and colon. To do this, we first performed a dose and time course study of alcohol-stimulated hyperpermeability of Caco-2 monolayers using the fluorescent dye FSA as a marker of permeability (Sanders et al., 1995). As seen in Figure 2A we tested concentrations of alcohol ranging from 0.05% to 0.5% over a period of 3 hours and found that these physiological concentrations of alcohol dose and time-dependently increased permeability of the intestinal epithelial cell monolayers to FSA probe. Caco-2 monolayer permeability was significantly (p< .05 vs. media control) increased by alcohol by 1 hour and further increased at 2 hr and 3 hr for alcohol concentrations as low as 0.1% (22mM, 1-3 drinks). We chose to use a 0.2% alcohol concentration (43mM, 2-4 drinks) for the remainder of the studies because it resulted in a significant increase in permeability at 2 hr and is approximately the average Blood Alcohol Level (BAL) found in our rat alcohol treatment model of alcoholic leaky gut and steatohepatitis (Keshavarzian et al., 2001; Keshavarzian et al., 2009).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2A. Alcohol (EtOH) treatment resulted in a dose and time dependent increased permeability to FSA in Caco-2 monolayers. Caco-2 cell monolayers were grown on collagen coated culture inserts and assessed for apical to basal flux of the fluorescent marker FSA as an in vitro model for intestinal permeability. The effects of alcohol (0.01%-0.5%; 2 mM-100 mM) on Caco-2 cell permeability to FSA probe were tested over time from 0.5-3 hours as described in Methods. Data shown are means for N=3 experiments using triplicate wells (N = 9 each point) and are presented as FSA clearance from the apical to basal chamber as nM/h/cm2 (SE bars of approx. ± 10% have been omitted for graphical clarity).*,+,# p<.05 vs. control for noted concentrations of 0.1%, 0.2%, and 0.5% EtOH respectively.

Fig. 2B. Alcohol time dependently increased Caco-2 permeability as measured by a decrease in TER. As a second measure of alcohol effects on Caco-2 permeability, we assessed the effects of alcohol (0.2%) over time (.25 hr-4 hr) on Transepithelial Resistance (TER) of Caco-2 cells grown on culture inserts as described in Methods. Data are means of triplicate wells from three experiments (N=9 each time point) and are presented as TER (Ωxcm2) % change from the original baseline TER at time “0”.“*” denotes alcohol treated cells had a significantly different TER than control cells (p≤.001).

As a second measure of Caco-2 permeability, we assessed the effects of alcohol treatment (0.2%) on Transepithelial Resistance (TER) measured as % change in Ωxcm2 (Figure 2B). This is another reliable measure of intestinal monolayer permeability (Shen et al., 2008; Rodriguez-Lagunas et al., 2010). Similar to data for FSA, alcohol significantly and in a time dependent manner led to a disruption in the monolayer barrier. Alcohol-induced decrease in TER was significant (P≤ .001) by 30 min and further dropped to 50% of the original TER level by 240 min (Figure 2B).

Alcohol Stimulates Expression of Circadian CLOCK and PER2 Proteins in Caco-2 Intestinal Epithelial Cells

We measured protein levels of two key canonical clock genes, Clock and Per2, in the Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells after alcohol treatment using western blots on lysates from the same inserts that were tested for permeability with TER measurements including time point-matched control well lysates for each time point. CLOCK protein binds to and upregulates transcription from the Per2 promoter to regulate 24h circadian rhythms (Reppert and Weaver, 2002). The total PER2 protein levels in the Caco-2 cells (mean relative density 2611+/- 183SE) is more than CLOCK (mean relative density 1674+/- 117SE) at baseline in non-alcohol treated cells (Figure 3, western blot gel, representative of 9 wells). We found that both PER2 and CLOCK gene proteins remained virtually unchanged in control wells through 240 minutes of the experiment. In contrast, both PER2 and CLOCK gene proteins in alcohol treated cells increased after 30 minutes of alcohol treatment and significantly increased after 60 and 240 minutes exposure to 0.2% alcohol (Figure 3). Compared to time point-matched controls for each protein (set as 100%), alcohol treatment resulted in mean increases of 225% for CLOCK protein (p=.024) and 240% for PER2 protein (p=.013) in Caco-2 cells after only 60 min of exposure. At the 240 min time point, alcohol treatment resulted in a mean increase of 237% for CLOCK (p=.036) and 315% for PER2 (p=.039). This alcohol-induced increase in PER2 and CLOCK proteins was associated with an alcohol-induced increase in FSA permeability across the monolayer and a drop in TER (Figure 2). The time course of increase in circadian gene proteins and disruption of monolayer barrier function was identical.

Fig. 3.

Alcohol stimulates increased expression of CLOCK and PER2 circadian proteins. To assess the effects of alcohol on circadian CLOCK and PER2 proteins, we assessed cell lysates from time point-paired control and alcohol treated (0.2%) cells tested in Fig. 2B for TER for CLOCK and PER2 proteins by western blotting with β-actin as a loading control. Western blot data shown (lower panels) are from single wells from a representative of 3 experiments in triplicate. The western blot gels demonstrate that total relative density of PER2 in the Caco-2 cells is more than CLOCK at baseline. The upper graphical data summarizes the densitometry results (as % change in Relative Density versus corresponding time-matched control ×100) from western blots from all 3 experiments ± SE (N=9 each data point). The baseline relative density in CLOCK and PER2 in control cells were arbitrarily set for each time point at 100. Then, % change in relative density of PER2 or CLOCK protein compared to their respective time point matched control were calculated. The bar graph represents percent change ×100 relative to the respective time point matched control. “*” denotes CLOCK protein was significantly increased vs. time point matched controls at 60 min (p≤.024) and 240 min (p≤.036); “+” denotes PER2 protein was significantly increased vs. time point matched controls at 60 min (p≤.013) and 240 min (p≤.039)..

Thus, alcohol disrupts intestinal monolayer barrier integrity. This disrupting effect of alcohol included both the “leak pathway” (increased FSA permeability) and “pore pathway” (drop in TER) (Turner, 2009). This disrupting effect of alcohol on barrier function correlated with an increase in CLOCK and PER2 proteins in the intestinal epithelial cells.

SiRNA knockdown of Clock or Per2 Circadian Genes Prevents Alcohol-induced Intestinal Epithelial Caco-2 Monolayer Hyperpermeability

We next tested the hypothesis that alcohol-induced stimulation of CLOCK and/or PER2 proteins is directly involved in the regulation of intestinal monolayer hyperpermeability in response to alcohol by using siRNA specific for either Clock or Per2. The Caco-2 cells were treated with siRNA for 72-96h prior to treatment with alcohol (N= 3 experiments for each, Clock and Per2 siRNA).

Figure 4 depicts TER and FSA permeability data and representative blots and the summarized histogram data for CLOCK protein (N=9 data points for each condition), As seen in Figure 4A and 4C, when compared to control siRNA treated Caco-2 cells to control for off target siRNA effects, siRNA specific inhibition of Clock significantly prevented alcohol-induced hyperpermeability (decreased TER and increased FSA) of Caco-2 cell monolayers at 60 min, 120 min, and 240 min after treatment (p≤ .001 TER, p≤ .05 FSA). To assess the levels of siRNA-mediated knockdown of Clock in our cells, we performed western blot analysis of lysates prepared from actual wells that were tested for permeability TER measurements and confirmed that we were able to knockdown CLOCK protein levels by about 70% in Clock siRNA and alcohol-treated cells compared to alcohol-treated control siRNA cells (Figure 4B).

Fig. 4.

SiRNA inhibition of CLOCK protein expression prevents alcohol-induced hyperpermeability of Caco-2 monolayers. To assess the role of alcohol-stimulation of CLOCK protein expression in the alcohol-induced increased permeability of Caco-2 monolayers, we inhibited CLOCK protein expression with siRNA specific for Clock and compared the effects to cells also treated with alcohol but treated with control nontargeting siRNA. Fig. 4A (upper panel) depicts permeability data which are presented as % Change TER (Ωxcm2) versus the “0” time point control for each condition. Data are means from triplicate wells in 3 experiments (total N=9) for each time point ± SE. Thus knock down of Clock gene by Clock specific siRNA prevented alcohol-induced monolayer hyperpermeability (drop in TER). * p≤.0001 vs. control siRNA; +p≤.001 vs. Clock siRNA+ EtOH. Fig. 4B middle panel shows western blot data from lysates from 4 representative inserts for each treatment group confirming that cells treated with Clock siRNA expressed significantly lower levels of CLOCK protein. Figure 4B lower histogram shows the summarized densitometry data for all western blots (N=9 inserts each group, each time point) confirming knockdown of CLOCK protein by about 70% in Clock siRNA and alcohol-treated cells compared to alcohol-treated control siRNA cells. Histogram data are expressed as % Relative Density ± SE versus the control siRNA treated cells not treated with alcohol (set as 100%). *p≤ .05 vs. control siRNA; #p≤.001vs. control siRNA + EtOH. Fig. 4C shows Caco-2 monolayer permeability data for FSA permeability for cells treated with alcohol ± siRNA for CLOCK as in Fig. 4A above shown as % change in FSA vs. control (control siRNA treated) cells for each data point.*p≤.05 vs. control siRNA + EtOH. Data are means ± SE for 3 experiments in triplicate (9 data points each).

Figure 5 depicts TER and FSA permeability data and representative blots and the summarized histogram data for PER2 protein (N=9 data points for each condition), As seen in Figure 5A and 5C, siRNA inhibition of Per2 also significantly inhibited alcohol-induced hyperpermeability (decreased TER and increased FSA respectively) in our intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cell model at 60 min, 120 min, and 240 min (p≤ .001 TER, p≤ .05 FSA). As shown in Figure 5B we were able to knockdown PER2 protein levels by about 70% in Per2 siRNA and alcohol-treated cells compared to alcohol-treated control siRNA cells. These data together with the data shown in Fig. 1 further confirm that this effect was specific for PER2 protein knockdown with siRNA. Thus, gene specific knockdown of CLOCK or PER2 circadian proteins significantly inhibits alcohol-induced disruption of the intestinal epithelial cell monolayer barrier function. This finding supports our hypothesis that intestinal circadian genes are involved in alcohol-induced gut leakiness and that alcohol stimulation of increased CLOCK and PER2 protein expression is required for alcohol-induced intestinal disruption of barrier function.

Alcohol Increases Intestinal Permeability in a Rat Alcohol Model of Leaky Gut

We have previously shown that daily alcohol gavage at a dose of 6g/kg/day of alcohol resulted in increased intestinal permeability after 4 weeks of daily alcohol consumption with histological evidence of steatohepatitis after 8 weeks of treatment in rats (Keshavarzian et al., 2001; Keshavarzian et al., 2009). In those studies, intestinal permeability was determined by measurement of urinary sugar excretion after an oral dose of sugars mixture (Farhadi et al., 2006). In the present study we used a newer modification of those gas chromatography-based methods of analysis (see Methods section) to re-analyze the urinary concentration of sucralose (a marker of total gut permeability) in urine samples from a subgroup of randomly selected control (N=9) and alcohol-fed (10wk, N=9) rats. We again found that chronic alcohol consumption caused gut leakiness. As seen in Figure 6A, daily alcohol gavage for 10 weeks resulted in significantly increased sucralose urinary excretion (p ≤ .003). We have previously determined (Keshavarzian et al.2001) that Blood Alcohol Levels (BAL) of these alcohol fed rats are in the range of .185-.249%, very comparable to our in vitro testing concentration of 0.2% alcohol indicating that these data are therefore physiologically relevant and comparable in terms of alcohol dose.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6A. Intestinal permeability measured by sucralose urinary excretion of an oral bolus is significantly increased in alcohol treated rats. Sprague-Dawley rats were gavaged twice daily with a control-chow or an alcohol-chow slurry for a total daily dose of 6g/kg/day alcohol for 10 weeks. Intestinal permeability was assessed at baseline and at 10 weeks by GC measurement of 6h urinary excretion of sucralose (a measure of whole gut permeability) after an oral dose of sucralose sugar mixture as described in Methods. Data are for N=9 rats for both control and alcohol treated groups and are presented as mean % urinary excretion of oral dose of sucralose ± SE. Chronic alcohol consumption resulted in significantly (*p≤.003) increased sucralose urinary excretion.

Fig. 6B. PER2 protein levels are significantly increased in the duodenum and proximal colon of alcohol fed rats. Rats were gavaged daily for 10 weeks with either control-chow or alcohol-chow slurry for a dose of 6g/kg/day alcohol and assessed for intestinal permeability as shown in Fig. 6A. After 10 weeks these same rats were sacrificed and lysates of intestinal tissue from either duodenum (left) or proximal colon (right) were prepared for western blotting with PER2 Ab or reprobed with anti-actin Ab as a control for equal loading. The upper panels in Figure 6B show representative western blots for PER2 protein (and actin control) of tissue lysates from individual representative rats from either the control (Con) or alcohol-fed group. As seen in the summarized densitometry data for all rats (N=9 each group) shown in lower Fig. 6B, PER2 protein was significantly increased in the intestinal tissue of alcohol fed rats compared to controls for both the duodenum (*p≤.008) and the proximal colon (*p≤.012) tissue.

Alcohol Stimulates Increased Expression of the Circadian Clock Gene Protein PER2 in the Intestinal Mucosa of Alcohol Fed Rats

Finally, we sought to determine if chronic alcohol feeding and increased intestinal permeability coincided in vivo with increased protein levels of the circadian PER2 protein as we had found in our in vitro alcohol treated Caco-2 cell model. We used western blotting of rat intestinal tissue from either the duodenum or the proximal colon from the same group of rats whose permeability data are presented in Fig. 6A. As seen in Figure 6B, alcohol fed rats with gut leakiness had significantly higher levels of PER2 protein levels in their duodenal (p≤ .008) and colonic (p≤ .012) mucosa compared to dextrose fed rats. Thus chronic alcohol consumption increased levels of the intestinal mucosa circadian PER2 protein levels in rats and this increase is associated with an increase in total gut permeability.

Discussion

The finding that a mutation of a canonical circadian clock gene, Clock, leads to obesity and characteristics of the metabolic syndrome in mice, opened up a new era for linking central and peripheral clocks, as well as linking the circadian molecular machinery to metabolism and energy balance (Turek et al., 2005). This salient finding has touched off an explosion of interest in both the circadian and metabolic fields as to the intersections at the behavioral, tissue, and molecular levels of the circadian clock and metabolic systems, and has led to major mechanistic discoveries of these interactions (Green et al., 2008; Laposky et al., 2008b; Nakahata et al., 2008; Ramsey et al., 2009). In contrast, few attempts have been made to examine the importance of circadian dysregulation of the brain-gut axis or intestine at the behavioral, physiological, or molecular levels despite considerable evidence that circadian rhythmicity is an important component of normal gut function (Scheving, 2000; Hoogerwerf et al., 2007). Indeed, our recent study (Preuss et al., 2008) demonstrating that chronic disruption of the central circadian clock in mice can lead to an increased vulnerability of the intestine to chemically (DSS)-induced colitis (a model where intestinal hyperpermeability is the primary pathogenic mechanism) strongly suggests that circadian clock machinery at the level of the brain-gut axis and/or in the intestine plays a pivotal role in the regulation of intestinal permeability in physiological and pathological states. As recently noted in a review on circadian rhythms and the GI tract, while there are clues suggestive of links between gastrointestinal disorders and peripheral circadian rhythms, “…understanding these links is still in its infancy”(Bron and Furness, 2009). The present findings support such linkages and strongly suggest a key role of intestinal circadian genes in the pathogenesis of alcohol-induced gut leakiness.

In the present study, we found that alcohol treatment of intestinal Caco-2 cells at the physiological concentration of 0.2% increased monolayer permeability measured by TER or FSA. Our findings are similar to our prior findings (Banan et al., 1999; Banan et al., 2000) that showed alcohol can disrupt intestinal monolayer integrity and thus the Caco-2 cell monolayer is an appropriate in vitro model for studying the mechanisms of alcohol-induced gut leakiness. Here we demonstrate for the first time that alcohol not only disrupts monolayer permeability, it also stimulates protein levels of the canonical circadian clock genes, Per2 and Clock. Most importantly, we found that the knock down of Clock or Per2 gene expression by siRNA prevents this alcohol-induced intestinal epithelial cell monolayer hyperpermeability and that PER2 protein is increased in the intestinal mucosa of alcohol fed rats with gut leakiness.

Our knock down experiments could support the hypothesis that upregulation of circadian genes by alcohol is a key mechanism of alcohol-induced intestinal hyperpermeability only if our knock down method is specific and we can rule out the off-target effects of siRNAs. In fact, siRNA transfection is widely acknowledged to have nonspecific off target effects and thus the accepted control is to base comparison not on untransfected cells but on cells transfected with a non-targeting ‘control’ siRNA. Thus, we have carefully controlled for off target effects of siRNA by what we believe is the most widely accepted approach. First, the gene specific siRNA we used is On Target Smartpool siRNA for Clock and Per2. Second, we controlled for general off target effects of siRNA transfection by using a non-targeting siRNA control (the principal control for off target effects). Third, we show in Fig. 1 that Per2 knockdown with siRNA resulting in 70% decreased PER2 protein had no significant effect on CLOCK protein levels. Figures 4 and 5 depict the data for cells treated with this control siRNA as well as cells treated with siRNA specific for either Clock or Per2 demonstrating that the control siRNA had no significant off target effect on CLOCK or PER2 protein expression while siRNA specific for Clock and Per2 significantly knocked down CLOCK and PER2 protein expression respectively. Together with data in Fig. 1, this supports that our siRNA inhibition of Clock and Per2 is specific and not due to general siRNA off target effects. Lastly, to control for off target effects of the specific Clock or Per2 siRNA on other proteins expression and for equal loading we also show protein data for β-actin in the representative blot. As shown in Figures 4 &5, β-actin protein level was not affected differentially by either the control or Clock or Per2 specific siRNA. Taken together these data and controls support the assertion that our siRNA data is specific for knockdown of Clock and Per2 expression and not due to nonspecific off target effects of siRNA.

It is noteworthy that we also found that knock down of Clock or Per2 genes in the non-alcohol exposed control Caco-2 cells did not affect intestinal monolayer permeability. This is not surprising because we hypothesized that alcohol stimulation of increased CLOCK and PER2 protein expression is required for alcohol-induced increase in intestinal permeability. Indeed, our data supported this hypothesis. In contrast, we did not propose that decreased expression of CLOCK or PER2 protein below baseline values results in a change in permeability in the normal state. Indeed, our data indicate that normal levels of either CLOCK or PER2 in the intestinal cells are not required for normal intestinal epithelial cell barrier function.

The finding that knockdown of both Clock and Per2 should have similar effects on permeability is consistent with what is known about the circadian clock gene circuit. The molecular interactions among clock genes have been partly identified. The CLOCK protein dimerizes with another circadian transcription factor protein BMAL1. This CLOCK-BMAL1dimer binds to sequences called E-box elements in the promoters of the circadian regulatory genes Per1-3, and Cry 1-2. The PER and CRY proteins then accumulate in the cytosol and are phosphorylated and then translocated back to the nucleus where they promote the degradation/inhibition of the CLOCK and BMAL1 proteins to end the cycle (Ukai and Ueda, 2010). Then the cycle begins again with this feedback transcriptional mechanism representing the core circadian oscillator. Other clock-controlled genes have been added to this network including NPAS2 and BMAL2 transcription factors and DEC1-2 proteins as well as kinases regulating phosphorylation of PER and CRY proteins and orphan receptors such as RevErb-α and ROR (Green et al., 2008; Ukai and Ueda, 2010). In addition to understanding regulation of the circadian timing mechanism itself, much recent attention has also been directed at identifying non-circadian targets of clock genes. In the present study, we only measured CLOCK and PER2 circadian proteins because they are products of key genes in the circadian clock gene circuit. Further studies are needed to assess the effects of alcohol on other circadian clock genes and circadian clock-controlled genes.

Our findings suggest that disruption of circadian rhythms in the brain-gut axis and/or intestinal circadian clock genes by alcohol might be central for promoting intestinal dysfunction and thus explain differential susceptibility to gut leakiness in alcoholics. This is a particularly attractive hypothesis in view of the finding that circadian genes directly control the expression of about 10%-20% of the genes in multiple tissues and organs, including those organs strongly affected by alcohol (e.g. brain, intestine, liver) (Duffield et al., 2002; Panda et al., 2002; Turek, 2008; Bozek et al., 2009). Furthermore, EtOH can induce changes in the central circadian clock in the brain that regulate the periods of behavioral and physiological rhythms, as well as at the molecular level where alcohol has been found to induce changes in the expression of canonical circadian clock genes(Chen et al., 2004; Rosenwasser et al., 2005b; Spanagel et al., 2005a; Seggio et al., 2009). Thus, such an alcohol-induced change in circadian clock gene expression at the intestinal epithelial cell level could have profound implications for alcohol-induced gut leakiness because the molecular clock in many central and peripheral tissues regulates the diurnal transcription of: (1) key genes in core pathways (Panda et al., 2002; Yoo et al., 2004; Laposky et al., 2008a), including genes such as NF-kB and iNOS that are involved in regulating the redox state of the tissue that is key in alcohol-induced gut leakiness(Banan et al., 2000; Banan et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2009); and (2) genes like tight junctional (TJ) proteins (Occludin, Claudins) and adherens junctional (AJ) proteins (E-cadherin) that make up the apical junctional complex (AJC). These proteins are essential in the regulation of intestinal permeability(Hoogerwerf et al., 2007; Bozek et al., 2009; Hughes et al., 2009; Polidarova et al., 2009; Turner, 2009; Yamato et al., 2010) and their function is regulated by circadian genes.

Particularly intriguing are the recent observations showing extensive polymorphisms in the circadian clock genes in humans including Period (Per) genes that have been shown to be involved in alcohol-induced changes in circadian rhythms in rodents (Spanagel et al., 2005b; Spanagel et al., 2005a; Perreau-Lenz et al., 2009). This observation raises the possibility that such polymorphisms could underlie the differential response of alcoholics to alcohol induced gut leakage, endotoxemia, and subsequent tissue injury like liver damage. However, in order to substantiate circadian genes as susceptibility factors for gut leakiness, further studies are needed to determine whether the expression of intestinal circadian genes is altered in alcoholic patients and whether the change in circadian gene levels or function can differentiate those alcoholics with gut leakiness and endotoxemia from those with normal intestinal permeability.

The discovery that the chronic disruption of the normal diurnal temporal environment can lead to an increased responsiveness of the intestines to alcohol induced gut leakage to endotoxins and associated ALD would have profound implications for addressing why only a sub-group of alcoholics develops ALD. Such a finding would immediately suggest new approaches for examining the temporal life style of alcoholics as well as possible therapeutic and preventive strategies for improving the overall temporal organization of alcoholics in order to prevent gut leakiness, endotoxemia and endotoxin-mediated disorders in alcoholics like cirrhosis (Adachi et al., 1995; Thurman, 1998; Keshavarzian et al., 1999; Rao et al., 2004) and neuronal damage (Diamond and Messing, 1994; Fadda and Rossetti, 1998; Brust, 2010). Furthermore, it would provide an opportunity for optimal risk stratification of organ dysfunction in alcoholics. While humans engaged in shift-work represent the obvious population that would be vulnerable to alcohol-induced gut leakage and associated ALD, they may only represent the “tip of the iceberg”(Turek, 2008). That is, temporal disorganization is a hallmark of the life-style of many alcoholics who have disturbances in their sleep-wake rhythm/cycle. The degree of such disruption of the diurnal sleep-wake rhythms, and undoubtedly other rhythms associated with the sleep-wake cycle (e.g. feeding rhythm), may be a causative factor for pre-disposing an alcoholic to alcohol-induced gut leakage to endotoxins (Laposky et al., 2008a).

Acknowledgments

Financial support. The study was supported by NIH grant AA13745 (to AK) and an unrestricted research gift from Mrs. and Mr. Larry Field (to AK).

Abbreviations

- ASH

alcoholic steatohepatitis

- BAL

blood alcohol level

- BGA

Brain-Gut axis

- EtOH

ethanol

- FSA

fluorescein-5-(and-6)-sulfonic acid trisodium salt

- SCN

suprachiasmatic nucleus

- TMSI

N-Trimethylsilylimidazole

Footnotes

Disclosers: the authors have no potential competing interests to declare.

Authors contributions: GS participated in developing experimental design, helped in data analysis, experiments and manuscript writing; CBF participated in developing experimental design, helped with data analysis, and writing the manuscript and submitting the manuscript; YT helped with experimental design and data analysis and manuscript writing; MS carried out experiments and made the figures and performed data analysis; LZ carried out experiments and performed data analysis; FWT participated in developing the experimental design, provided the expertise in the field of circadian research, helped with data analysis, and manuscript writing; AK conceived the hypothesis, participated in developing experimental design, and helped with data analysis and manuscript writing.

References

- Adachi Y, Moore LE, Bradford BU, Gao W, Thurman RG. Antibiotics prevent liver injury in rats following long-term exposure to ethanol. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:218–224. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banan A, Choudhary S, Zhang Y, Fields JZ, Keshavarzian A. Ethanol-induced barrier dysfunction and its prevention by growth factors in human intestinal monolayers: evidence for oxidative and cytoskeletal mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:1075–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banan A, Fields JZ, Decker H, Zhang Y, Keshavarzian A. Nitric oxide and its metabolites mediate ethanol-induced microtubule disruption and intestinal barrier dysfunction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:997–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banan A, Keshavarzian A, Zhang L, Shaikh M, Forsyth CB, Tang Y, Fields JZ. NF-kappaB activation as a key mechanism in ethanol-induced disruption of the F-actin cytoskeleton and monolayer barrier integrity in intestinal epithelium. Alcohol. 2007;41:447–460. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell-Pedersen D, Cassone VM, Earnest DJ, Golden SS, Hardin PE, Thomas TL, Zoran MJ. Circadian rhythms from multiple oscillators: lessons from diverse organisms. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:544–556. doi: 10.1038/nrg1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozek K, Relogio A, Kielbasa SM, Heine M, Dame C, Kramer A, Herzel H. Regulation of clock-controlled genes in mammals. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bron R, Furness JB. Rhythm of digestion: keeping time in the gastrointestinal tract. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2009;36:1041–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2009.05254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brust JC. Ethanol and cognition: indirect effects, neurotoxicity and neuroprotection: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7:1540–1557. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7041540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CP, Kuhn P, Advis JP, Sarkar DK. Chronic ethanol consumption impairs the circadian rhythm of pro-opiomelanocortin and period genes mRNA expression in the hypothalamus of the male rat. J Neurochem. 2004;88:1547–1554. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond I, Messing RO. Neurologic effects of alcoholism. West J Med. 1994;161:279–287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffield GE, Best JD, Meurers BH, Bittner A, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC. Circadian programs of transcriptional activation, signaling, and protein turnover revealed by microarray analysis of mammalian cells. Curr Biol. 2002;12:551–557. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00765-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadda F, Rossetti ZL. Chronic ethanol consumption: from neuroadaptation to neurodegeneration. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;56:385–431. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhadi A, Keshavarzian A, Fields JZ, Sheikh M, Banan A. Resolution of common dietary sugars from probe sugars for test of intestinal permeability using capillary column gas chromatography. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2006;836:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth CB, Pulai J, Loeser RF. Fibronectin fragments and blocking antibodies to alpha2beta1 and alpha5beta1 integrins stimulate mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling and increase collagenase 3 (matrix metalloproteinase 13) production by human articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2368–2376. doi: 10.1002/art.10502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth CB, Tang Y, Shaikh M, Zhang L, Keshavarzian A. Alcohol Stimulates Activation of Snail, Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Signaling, and Biomarkers of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Colon and Breast Cancer Cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:19–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01061.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth CB, Banan A, Farhadi A, Fields JZ, Tang Y, Shaikh M, Zhang LJ, Engen PA, Keshavarzian A. Regulation of oxidant-induced intestinal permeability by metalloprotease-dependent epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:84–97. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.113019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gareau MG, Jury J, Perdue MH. Neonatal maternal separation of rat pups results in abnormal cholinergic regulation of epithelial permeability. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G198–203. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00392.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dufour MC, Harford TC. Epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 1988;8:12–25. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CB, Takahashi JS, Bass J. The meter of metabolism. Cell. 2008;134:728–742. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings MH, Reddy AB, Maywood ES. A clockwork web: circadian timing in brain and periphery, in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:649–661. doi: 10.1038/nrn1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogerwerf WA, Hellmich HL, Cornelissen G, Halberg F, Shahinian VB, Bostwick J, Savidge TC, Cassone VM. Clock gene expression in the murine gastrointestinal tract: endogenous rhythmicity and effects of a feeding regimen. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1250–1260. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, DiTacchio L, Hayes KR, Vollmers C, Pulivarthy S, Baggs JE, Panda S, Hogenesch JB. Harmonics of circadian gene transcription in mammals. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarzian A, Holmes EW, Patel M, Iber F, Fields JZ, Pethkar S. Leaky gut in alcoholic cirrhosis: a possible mechanism for alcohol-induced liver damage. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:200–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarzian A, Choudhary S, Holmes EW, Yong S, Banan A, Jakate S, Fields JZ. Preventing gut leakiness by oats supplementation ameliorates alcohol-induced liver damage in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:442–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarzian A, Farhadi A, Forsyth CB, Rangan J, Jakate S, Shaikh M, Banan A, Fields JZ. Evidence that chronic alcohol exposure promotes intestinal oxidative stress, intestinal hyperpermeability and endotoxemia prior to development of alcoholic steatohepatitis in rats. J Hepatol. 2009;50:538–547. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laposky AD, Bass J, Kohsaka A, Turek FW. Sleep and circadian rhythms: key components in the regulation of energy metabolism. FEBS Lett. 2008a;582:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laposky AD, Bradley MA, Williams DL, Bass J, Turek FW. Sleep-wake regulation is altered in leptin-resistant (db/db) genetically obese and diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008b;295:R2059–2066. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00026.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy B, Zakaria A, Glass JD, Prosser RA. Ethanol Modulates Mammalian Circadian Clock Phase Resetting Through Extrasynaptic Gaba Receptor Activation. Neuroscience. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistlberger RE, Nadeau J. Ethanol and circadian rhythms in the Syrian hamster: effects on entrained phase, reentrainment rate, and period. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1992;43:159–165. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90652-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahata Y, Yoshida M, Takano A, Soma H, Yamamoto T, Yasuda A, Nakatsu T, Takumi T. A direct repeat of E-box-like elements is required for cell-autonomous circadian rhythm of clock genes. BMC Mol Biol. 2008;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X, Hussain MM. Clock is important for food and circadian regulation of macronutrient absorption in mice. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1800–1813. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M900085-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda S, Antoch MP, Miller BH, Su AI, Schook AB, Straume M, Schultz PG, Kay SA, Takahashi JS, Hogenesch JB. Coordinated transcription of key pathways in the mouse by the circadian clock. Cell. 2002;109:307–320. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00722-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreau-Lenz S, Zghoul T, de Fonseca FR, Spanagel R, Bilbao A. Circadian regulation of central ethanol sensitivity by the mPer2 gene. Addict Biol. 2009;14:253–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polidarova L, Sotak M, Sladek M, Pacha J, Sumova A. Temporal gradient in the clock gene and cell-cycle checkpoint kinase Wee1 expression along the gut. Chronobiol Int. 2009;26:607–620. doi: 10.1080/07420520902924889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss F, Tang Y, Laposky AD, Arble D, Keshavarzian A, Turek FW. Adverse effects of chronic circadian desynchronization in animals in a “challenging” environment. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R2034–2040. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00118.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit V, Bode JC, Bode C, Brenner DA, Choudhry MA, Hamilton F, Kang YJ, Keshavarzian A, Rao R, Sartor RB, Swanson C, Turner JR. Alcohol, intestinal bacterial growth, intestinal permeability to endotoxin, and medical consequences: summary of a symposium. Alcohol. 2008;42:349–361. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.03.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey KM, Yoshino J, Brace CS, Abrassart D, Kobayashi Y, Marcheva B, Hong HK, Chong JL, Buhr ED, Lee C, Takahashi JS, Imai S, Bass J. Circadian clock feedback cycle through NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis. Science. 2009;324:651–654. doi: 10.1126/science.1171641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao RK, Seth A, Sheth P. Recent Advances in Alcoholic Liver Disease I. Role of intestinal permeability and endotoxemia in alcoholic liver disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G881–884. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00006.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature. 2002;418:935–941. doi: 10.1038/nature00965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Lagunas MJ, Martin-Venegas R, Moreno JJ, Ferrer R. PGE2 promotes Ca2+-mediated epithelial barrier disruption through EP1 and EP4 receptors in Caco-2 cell monolayers. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C324–334. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00397.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwasser AM, Logan RW, Fecteau ME. Chronic ethanol intake alters circadian period-responses to brief light pulses in rats. Chronobiol Int. 2005a;22:227–236. doi: 10.1081/cbi-200053496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwasser AM, Fecteau ME, Logan RW. Effects of ethanol intake and ethanol withdrawal on free-running circadian activity rhythms in rats. Physiol Behav. 2005b;84:537–542. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders SE, Madara JL, McGuirk DK, Gelman DS, Colgan SP. Assessment of inflammatory events in epithelial permeability: a rapid screening method using fluorescein dextrans. Epithelial Cell Biol. 1995;4:25–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheving LA. Biological clocks and the digestive system. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:536–549. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.9305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seggio JA, Fixaris MC, Reed JD, Logan RW, Rosenwasser AM. Chronic ethanol intake alters circadian phase shifting and free-running period in mice. J Biol Rhythms. 2009;24:304–312. doi: 10.1177/0748730409338449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Weber CR, Turner JR. The tight junction protein complex undergoes rapid and continuous molecular remodeling at steady state. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:683–695. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200711165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Rosenwasser AM, Schumann G, Sarkar DK. Alcohol consumption and the body's biological clock. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005a;29:1550–1557. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000175074.70807.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Pendyala G, Abarca C, Zghoul T, Sanchis-Segura C, Magnone MC, Lascorz J, Depner M, Holzberg D, Soyka M, Schreiber S, Matsuda F, Lathrop M, Schumann G, Albrecht U. The clock gene Per2 influences the glutamatergic system and modulates alcohol consumption. Nat Med. 2005b;11:35–42. doi: 10.1038/nm1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasi C, Orlandelli E. Role of the brain-gut axis in the pathophysiology of Crohn's disease. Dig Dis. 2008;26:156–166. doi: 10.1159/000116774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Forsyth CB, Farhadi A, Rangan J, Jakate S, Shaikh M, Banan A, Fields JZ, Keshavarzian A. Nitric oxide-mediated intestinal injury is required for alcohol-induced gut leakiness and liver damage. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1220–1230. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00946.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurman RG. II. Alcoholic liver injury involves activation of Kupffer cells by endotoxin. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G605–611. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.4.G605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turek FW. Circadian clocks: tips from the tip of the iceberg. Nature. 2008;456:881–883. doi: 10.1038/456881a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turek FW, Joshu C, Kohsaka A, Lin E, Ivanova G, McDearmon E, Laposky A, Losee-Olson S, Easton A, Jensen DR, Eckel RH, Takahashi JS, Bass J. Obesity and metabolic syndrome in circadian Clock mutant mice. Science. 2005;308:1043–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.1108750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JR. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:799–809. doi: 10.1038/nri2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukai H, Ueda HR. Systems biology of mammalian circadian clocks. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:579–603. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-073109-130051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamato M, Ito T, Iwatani H, Yamato M, Imai E, Rakugi H. E-cadherin and claudin-4 expression has circadian rhythm in adult rat kidney. J Nephrol. 2010;23:102–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Yamazaki S, Lowrey PL, Shimomura K, Ko CH, Buhr ED, Siepka SM, Hong HK, Oh WJ, Yoo OJ, Menaker M, Takahashi JS. PERIOD2:LUCIFERASE real-time reporting of circadian dynamics reveals persistent circadian oscillations in mouse peripheral tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5339–5346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308709101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]