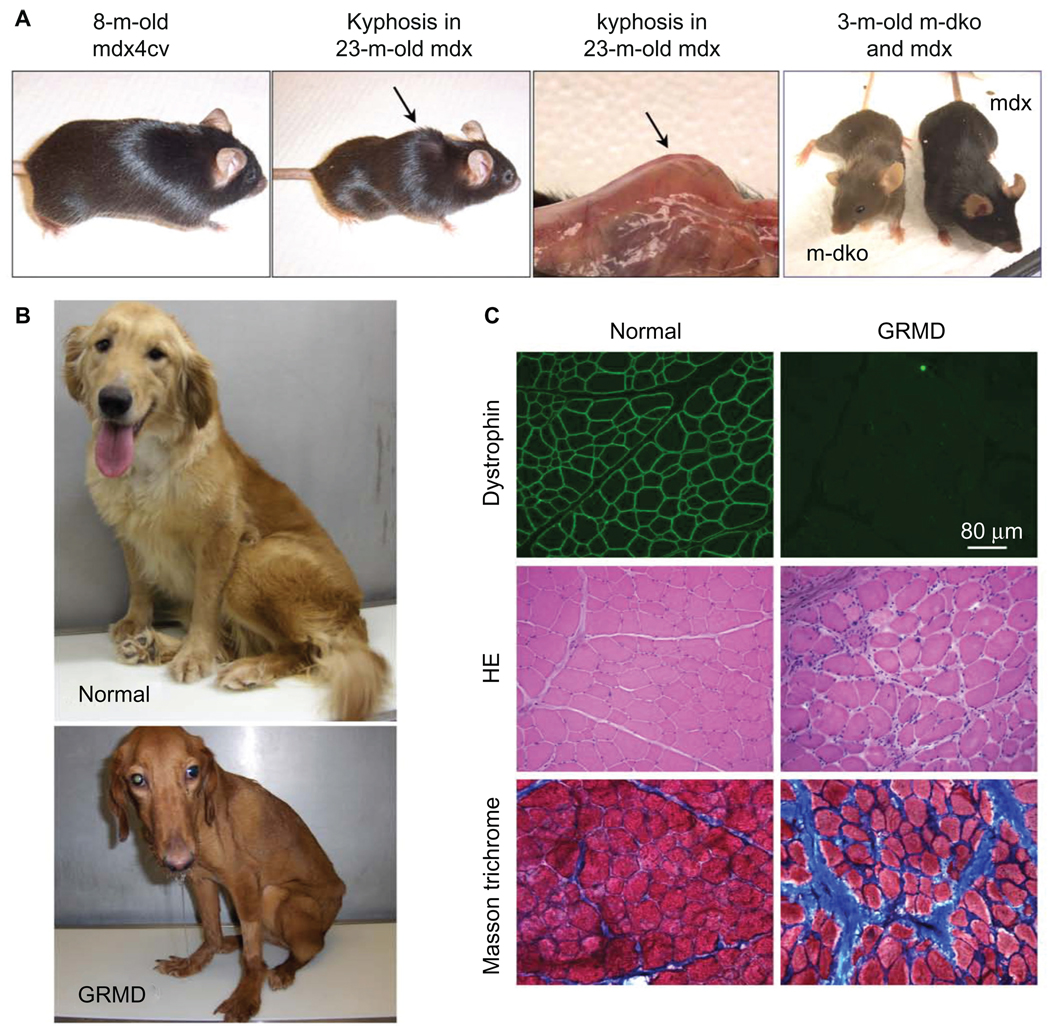

Figure 2.

Mouse and dog models of DMD. A) Representative pictures of an 8-month-old dystrophin-deficient mdx4cv mouse (left panel), a 23-month-old mdx mouse (middle two panels), and a 3-month-old myoD/dystrophin double knockout (m-dKO) mouse and a 3-month-old mdx mouse (right panel). Adult dystrophin-null mice do not display clinical symptoms (left panel). The middle two panels show body emaciation and mouse in aged dystrophin-null mouse. (Arrow points to kyphosis seen in aged mdx mice. The left panel is a full-body view. The right-side panel represents a close view of kyphosis after the skin is removed.) The difference in the genetic background results in different fur color in m-dKO (brown) and mdx (black) mice (right panel). Findings from dKO mice may be biased by their mixed genetic background. B) Representative pictures of a 2-year-old normal golden retriever (top) and an affected GRMD (bottom) dog. The affected dog shows body and limb muscle atrophy, drooling, and ulnocarpal joints (forelimbs) dropped to the ground level. C) Representative muscle immunofluorescence staining and histopathology staining in normal (left panels) and GRMD (right panels) dogs. Dystrophin is detected by an antibody (Dys-1) specific for spectrin-like repeats 6–8 (top row). Muscle pathology is revealed by hematoxylin–eosin (HE) staining (middle row) and Masson’s trichrome staining (bottom row). HE staining shows inflammatory cell infiltration, central nucleation, and variable myofiber size. Masson’s trichrome staining shows fibrosis. Blue color in Masson’s trichrome staining images represents fibrotic tissue.

Abbreviations: DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; GRMD, golden retriever muscular dystrophy.