Abstract

Potassium channels regulate numerous aspects of neuronal excitability, and several voltage-gated K+ channel subunits have been identified in pyramidal neurons of rat neocortex. Previous studies have either considered the development of outward current as a whole or divided currents into transient, A-type and persistent, delayed rectifier components but did not differentiate between current components defined by α-subunit type. To facilitate comparisons of studies reporting K+ currents from animals of different ages and to understand the functional roles of specific current components, we characterized the postnatal development of identified Kv channel-mediated currents in pyramidal neurons from layers II/III from rat somatosensory cortex. Both the persistent/slowly inactivating and transient components of the total K+ current increased in density with postnatal age. We used specific pharmacological agents to test the relative contributions of putative Kv1- and Kv2-mediated currents (100 nM α-dendrotoxin and 600 nM stromatoxin, respectively). A combination of voltage protocol, pharmacology, and curve fitting was used to isolate the rapidly inactivating A-type current. We found that the density of all identified current components increased with postnatal age, approaching a plateau at 3–5 wk. We found no significant changes in the relative proportions or kinetics of any component between postnatal weeks 1 and 5, except that the activation time constant for A-type current was longer at 1 wk. The putative Kv2-mediated component was the largest at all ages. Immunocytochemistry indicated that protein expression for Kv4.2, Kv4.3, Kv1.4, and Kv2.1 increased between 1 wk and 4–5 wk of age.

Keywords: Kv channel, somatosensory cortex, voltage clamp, A current, delayed rectifier

at birth, the rodent somatosensory system is immature, and somatosensory cortex undergoes dramatic changes over the first postnatal month. Neocortical pyramidal cells are generated prenatally in an “inside-out” laminar pattern (Caviness 1982; Caviness et al. 2009; Takahashi et al. 1994), and pyramidal cell morphology and physiology mature after birth (Bahrey and Moody 2003; Beique et al. 2004; Blue and Parnevalas 1983; Christophe et al. 2005; Kasper et al. 1994a, 1994b; Kriegstein et al. 1987; Kristt 1978; Lorenzon and Foehring 1993; Maravall et al. 2004a, 2004b; McCormick and Prince 1987; Metherate and Aramkis 1999; Miller 1981; Miller and Peters 1981; Oswald and Reyes 2008; Wise and Jones 1976). Cortical circuits are tuned postnatally. For example, synaptogenesis peaks in the second postnatal week (Micheva and Beaulieu 1996) and synapse numbers increase until ∼P32 (De Felipe et al. 1997). Activity has been shown to affect these processes (Feldman et al. 1999; Hentsch 2005).

Neonatal neurons are notoriously sluggish in response to stimulation (Crain 1952; Purpura et al. 1965) because of immature excitatory synaptic input (Purpura et al. 1965) and immature expression of ion channels (Bahrey and Moody 2003; Huguenard et al. 1988). Pyramidal cell resting membrane potential (RMP) becomes more hyperpolarized with postnatal development and input resistance and membrane time constant decrease (Bahrey and Moody 2003; Beique et al. 2004; Christophe et al. 2005; Kasper et al. 1994a, 1994b; Lorenzon and Foehring 1993; Maravall et al. 2004a; McCormick and Prince 1987; Metherate and Aramkis 1999; Oswald and Reyes 2008; Tyzio et al. 2003). Repetitive firing behavior also changes with age (Bahrey and Moody 2003; Christophe et al. 2005; Kasper et al. 1994a, 1994b; Lorenzon and Foehring 1993; Maravall et al. 2004a, 2004b; McCormick and Prince 1987; Metherate and Aramkis 1999; Oswald and Reyes 2008; van Brederode et al. 2000; Zhang 2004). In mature pyramidal neurons, voltage-gated K+ channels contribute to the filtering and integration of synaptic inputs, as well as shaping firing rates and pattern (Guan et al. 2007a; Higgs and Spain 2009; Schwindt et al. 1988). Developmental changes in these channels should therefore play significant roles in the maturation of pyramidal cell function.

Previous electrophysiological studies of development have considered the outward current as a whole, divided currents into transient A-type and persistent delayed rectifier (DR) components (Bahrey and Moody 2003; Hammill et al. 1991; Zhou and Hablitz 1996a), or separated current components based upon inactivation kinetics (Foehring and Surmeier 1993; Locke and Nerbonne 1997a, 1997b). Much of the literature also concerns data from immature animals over limited age ranges that vary between laboratories. Little is known, however, about development of current components identified by molecular composition.

Several voltage-gated potassium channel (Kv) subunits and currents have been identified in the pyramidal neurons of juvenile rat cortex (Bekkers 2000a, 2000b; Guan et al. 2005, 2006, 2007b; Hamill et al. 1991; Korngreen and Sakmann 2000; Nerbonne et al. 2008; Norris and Nerbonne 2010; Yuan et al. 2005), and developmental changes in action potential (AP) and firing properties suggest that Kv channel subunits may be developmentally regulated. To help understand the functional roles of specific current components and to facilitate comparisons between studies reporting K+ currents from animals of different ages, we systematically characterized the expression of the total potassium current and the relative contributions of putative Kv1- and Kv2-mediated current and A-type current during the first 5 wk of postnatal development of pyramidal cells from rat somatosensory cortex.

METHODS

Tissue Preparation

These studies were performed on Sprague-Dawley rats aged P3–P38. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee, University of Tennessee Health Science Center. Briefly, the animal was placed into a sealed plastic container in which gauze soaked with isofluorane was placed under a fiberglass screen floor. The rats were anesthetized with isofluorane until they were areflexive. The animals were decapitated, and the brain was removed and held in ice-cold cutting solution. The cutting solution contained (in mM) 250 sucrose, 2.5 KCl, 1 NaH2PO4, 11 dextrose, 4 MgSO4, 0.1 CaCl2, 15 HEPES (pH = 7.3–7.4; 300 mosmol/kgH2O). Four hundred-micrometer coronal slices of the fronto-parietal regions were cut with a vibrating tissue slicer (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). The slices were then transferred to a mesh surface in a chamber containing artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF), which was continuously bubbled with a 95% O2-5% CO2 (carbogen) mixture at room temperature. The aCSF contained (mM) 125 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 20 dextrose (pH = 7.4; 310 mosmol/kgH2O).

Acute Isolation of Neurons

The supragranular layers (I–III) of primary somatosensory cortex were dissected from brain slices into 2- to 3-mm-wide pieces. Four to eight tissue pieces were then transferred to oxygenated aCSF (35°C) with added enzyme (Sigma protease type XIV, 1.2 mg/ml; Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO). After 10–30 min of incubation in enzyme, the tissue pieces were washed with sodium isethionate solution, which consisted of (in mM) 140 sodium isethionate, 2 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 23 dextrose, 15 HEPES (pH = 7.3; 300 mosmol/kgH2O). This solution and the enzyme-treated tissue pieces were triturated with three successively smaller fire-polished pipettes to release individual neuronal somata. The supernatant from each trituration step was collected, transferred to a fresh container, and plated onto a plastic petri dish (Nunc, Rochester, NY) on an inverted microscope stage. After 5–8 min of settling time, a uniform background flow (∼1 ml/min) of HEPES-buffered saline solution (HBSS) was established in the dish. HBSS consisted of (mM) 138 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 20 dextrose (pH = 7.3; 300 mosmol/kgH2O). Typical yields of healthy cells are greater in younger animals (1–2 wk vs. ≥4 wk).

Electrophysiology

Whole cell patch-clamp recordings were performed on acutely dissociated pyramidal neurons at room temperature (20–22°C). Pyramidal cells were identified by soma shape and the presence of a single apical dendrite (of <25 μm in length). A multibarrel array of glass capillaries (500-μm outer diameter) was used to apply external recording solutions. External solutions were changed by moving the active barrel (from which the solution flows) so as to center the flow upon the recorded cell. The external solution for isolating the outward K+ current contained (mM) 140 sodium isethionate, 3 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 12 dextrose, 10 HEPES, 1.9 CaCl2, 0.001 tetrodotoxin (TTX) for blocking Na+ channels, and in most experiments, 0.1 CdCl2 for blocking Ca2+ channels.

Voltage-clamp recordings were made with a DAGAN 8900 (Minneapolis, MN) amplifier. Corning 8250 capillary glass (Garner Glass, Claremont, CA) was used to create electrodes on a model P-87 Flaming/Brown micropipette puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). Electrodes were fire-polished and filled with an internal solution consisting of (mM) 85 potassium methylsulfate, 63 KOH, 2 MgCl2, 30 HEPES, 2 adenosine triphosphate disodium (ATP), 0.2 guanosine 5′-triphosphate sodium salt (GTP), 15 creatine phosphate, 0.1 leupeptin, 10 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA: pH = 7.2; 270 mosmol/kgH2O). Electrode resistances were 1.0–1.8 MΩ. Series resistance was usually compensated by 70–90%. Cells with calculated series resistance errors of >5 mV were discarded [series resistance error (mV) = series resistance after compensation (MΩ) multiplied by peak current (pA)]. Membrane potentials were corrected for the measured liquid junction potential (+8 mV). K+ currents were filtered at a cutoff frequency of 5 kHz and sampled at a rate of 20 kHz. Linear leak currents and capacitative artifacts were subtracted with an online P/4 or P/6 protocol. All measurements and recordings were conducted with pCLAMP 8 software (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) within ∼5 min after obtaining whole cell mode.

Current Isolation

We assessed the amplitude of outward K+ currents by 500-ms steps to +10 mV from a holding potential (HP) of −70 mV. The test steps were repeated at intervals of 15 s. Unless otherwise noted, we included TTX (1 μM) and 100 μM Cd2+ in the extracellular solutions to block Na+ and Ca2+ currents, respectively. The internal solution included 10 mM BAPTA to prevent activation of Ca2+-dependent currents. Current components due to Kv1 or Kv2 subunits were isolated pharmacologically. All peptide toxins were obtained from Alomone Labs (Jerusalem, Israel). BSA (0.1%) was added to the external solutions to prevent peptides from binding to glass and plastic vessels. We previously determined dose-response relationships for the blockers, and we chose doses that were specific for the relevant subunits (Guan et al. 2006, 2007b). To study putative Kv1-mediated current (Guan et al. 2006), we applied 100 nM α-dendrotoxin (DTX, blocks current through channels containing Kv1.1, Kv1.2, or Kv1.6 subunits; Harvey and Robertson 2004) and 10–30 nM margatoxin (MTX, blocks Kv1.3-containing channels; Garcia-Calvo et al. 1993). The putative Kv1-mediated current was defined as the difference between currents recorded in control solution and currents in the presence of DTX plus MTX. The doses for DTX and MTX were highly selective for Kv1 subunits and saturating (Guan et al. 2006).

Putative Kv2-mediated current was defined as the current sensitive to 600 nM stromatoxin (ScTx; Escoubas et al. 2002). ScTx inhibits the Kv2 subunit-mediated current in pyramidal neurons with an IC50 of 160 nM (Guan et al. 2007b). At 600 nM ScTx blocks >70% of the ScTx-sensitive current (Guan et al. 2007b). ScTx doses higher than 600 nM would block more Kv2 channels but would increase experiment cost, and the subunit selectivity at high doses of ScTx is uncertain. At this dose, ScTx also blocks A-type current in most cells (see below). The ScTx block is voltage dependent, with unblocking occurring at potentials more depolarized than approximately +10 mV (Escoubas et al. 2002; Guan et al. 2007b).

Run-down of current can be an issue in K+ current recordings. We previously measured this run-down and noted that after a stable period of 3–5 min the current runs down. The current that runs down first has very slow activation kinetics compared with the putative Kv1 or Kv2 components (Guan et al. 2006, 2007a). All of our data for percent block were obtained within the initial stable period for current amplitude. In addition, we continually monitored series resistance (see above). Since recordings are typically <10 min, reported changes in cell input resistance after long recordings with K-methyl sulfate internals (Kaczorowski et al. 2007) are minimized.

For experiments designed to study the rapidly activating and inactivating A-type current, we used an external recording solution without Cd2+ present because Cd2+ shifts the voltage dependence of both activation and inactivation of Kv4 channels to more depolarized potentials and slows their kinetics (Guan et al. 2007b; Song et al. 1998; Wickenden et al. 1999). Our initial method for isolating the A-type current was via a voltage protocol. DTX and MTX were present in all recordings to block Kv1-mediated currents. A −40 mV HP was used to inactivate most of the outward current. After an initial period at −40 mV to allow the holding current to stabilize, a step is made to +10 mV for 500 ms. The cell is returned to −40 mV for 5 s, and then a prepulse to −70 mV (150-ms duration) is applied to allow preferential recovery of the A-type current. This prepulse duration is long enough to recover most of the A current (taurecovery = 61 ± 5 ms, n = 3) but is too short to recover the majority of the DR currents (Foehring and Surmeier 1993; Guan et al. 2006, 2007b). We compared all age groups, using a test potential to +10 mV for 500 ms, repeated every 15 s. A-type current was defined as the difference between current during the test potential after the prepulse and current during a test pulse without the prepulse. Curve fitting was used to further separate the A current from DR currents (see results). In an additional set of experiments, we studied steady-state activation and inactivation of A-type current at 1 wk and 4–5 wk of age. In those experiments, 30 mM TEA replaced equimolar NaCl in the external solution to further isolate the A current (together with biophysics and curve fitting).

Immunocytochemistry

Animals (n = 4 at P6–P9 and n = 4 at P26–P38) were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg ip). The anesthetized animals were transcardially perfused with 0.01 M sodium phosphate buffer plus 0.89% NaCl (PBS) followed by PBS-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% picric acid. (For Kv4.2, we also used 4% paraformaldehyde without picric acid, postfixed for ∼12 h, and washed overnight in 0.1 M PBS; Burkhalter et al. 2006). Brains were removed, postfixed for ∼12 h at 4°C, and then blocked and postfixed for ∼24 h. Sections through the cortex were taken at 50 μm on a vibrating microtome (Leica VT1000S), rinsed in PBS, and incubated in 5% normal goat serum with 3% H2O2 for 1–2 h to reduce background staining. For Kv4.2, we also tried treatment with 0.5% sodium borohydride, followed by 0.3% H2O2 and then 50% ethanol (Burkhalter et al. 2006). All antibodies used were monoclonal (NeuroMab, Univ. of California, Davis, CA) and purchased from Antibodies Incorporated (Davis, CA). These included the K13/31 clone (Kv1.4), K57/1 clone (Kv4.2), K75/41 clone (Kv4.3), and K89/34 clone (Kv2.1). Antibodies were first tested at various concentrations (1:100 to 1:1,000) in PBS and 0.5% Triton X-100 (PBS-TX). After this dilution screening, the same concentration for a particular antibody was then used to compare across ages.

After overnight incubation with the primary antibody (1:200 to 1:500), the sections were incubated overnight in a secondary antibody (1:200) consisting of goat anti-mouse (GAM)-Alexa Fluor 594 or rabbit anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 568 (for Kv4.2 only) conjugates, all at 4°C. The sections were rinsed in PBS-TX, mounted on gelatin-coated slides, and coverslipped with a solution of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA: 2.4 g), 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO: 0.625 g), glycerin (6 g), PBS (12 ml), and 6 ml of distilled water (recipe courtesy of Bioengineering Confocal and Multiphoton Imaging Core Facility, University of Pennsylvania; http://www.seas.upenn.edu/∼confocal/antifade.html#PVA-DABCO%20Mounting%20Media). These sections were viewed with a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope using either a DPSS (for Alexa Fluor 568; 561 nm peak excitation) or a HeNe (for Alexa 594; 594 nm peak excitation) laser. The optical section thickness was 1–2 μm. Most sections had full penetrance of primary antibody (∼50 μm). Sections were viewed singly or in stacks of 5–12 optical sections. For comparative purposes across age, laser settings (pinhole, power, gain, and pixel resolution) were made from just below saturation in the oldest animals, where fluorescence was brightest, and reused for other ages. Images were captured with Zen10 software and saved in native and tiff formats. The final confocal figures were made in Canvas 8, without alteration in dynamic range.

Statistics

Data are presented as means ± SD in the text and tables and as means ± SE in figures. Prism Software version 4 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used for statistical tests of significance. Student's t-test was used to compare means of two samples. One-way ANOVA was used to test differences for three or more groups. If the ANOVA was significant, we used the post hoc Tukey's test to determine which specific means were different. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Our isolation procedure restricted recordings to pyramidal cells from layers II–III (see methods) of rat primary somatosensory cortex. We used acutely dissociated neurons to allow normal in situ development before cell harvest and to facilitate spatial control of voltage (by removing cell processes) and rapid exchange of extracellular solutions. Because these cells have had the axon and dendrites removed, our conclusions are restricted to currents in the soma and proximal (<25 μm) apical dendrites. Total potassium current was studied in 140 neurons. The effects of combined Kv1 blockers (DTX + MTX) were studied in 109 cells. ScTx-sensitive current was studied in 56 cells. Some of the included Kv1 and Kv2 data from animals aged 4–5 wk were taken from our previous work (Guan et al. 2006, 2007a, 2007b). A-type currents were studied in the absence of extracellular Cd2+ in an additional group of 80 cells.

For analysis, we grouped the data according to animal age: 7 ± 3 days was considered week 1, 14 ± 3 days = week 2, 21 ± 3 days = week 3, 28 ± 3 days = week 4, and 35 ± 3 days = week 5. We used peak current and time to peak (TTP) to characterize the total potassium current and toxin-sensitive current at +10 mV and used the current at 500 ms to describe the “steady-state” amplitude of these currents.

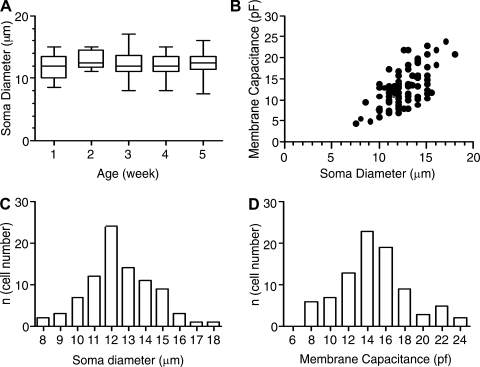

Figure 1 characterizes the population of neocortical pyramidal cells that we studied. Diameters of cell somata were measured with a graduated ocular scale under the microscope (n = 87). Whole cell capacitance was measured from the current in response to a 10-ms step from −70 mV to −80 mV as Q/10 mV (where Q is the total charge displaced by the step: the time integral of the current). For the recorded cells, there were no significant differences between age groups for soma diameters or whole cell capacitance (Kruskal-Wallis test; Fig. 1, A and B), suggesting that cells that survived the dissociation conditions and our selection process were of similar size at all ages. Membrane capacitance increased with soma diameter (Fig. 1B), and the histograms of soma diameters (P > 0.24) and membrane capacitance (P > 0.65) were normally distributed (D'Agostino and Pearson omnibus normality test; Fig. 1, C and D).

Fig. 1.

Dimensions of recorded cells. A: soma diameter did not change significantly with age for the recorded cells. B: whole cell capacitance (Cm) vs. soma diameter for the recorded cells (all ages pooled). C: histogram for cell diameter (all ages pooled) suggests a single, normally distributed sample. D: histogram for whole cell capacitance (all ages pooled) suggests a single, normally distributed sample.

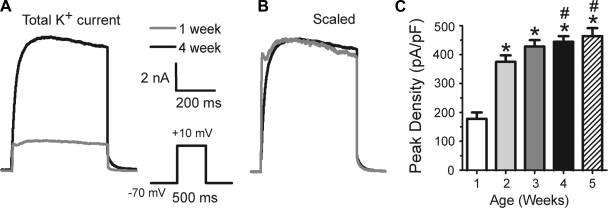

For comparison with earlier studies, we first studied the total outward potassium current as a function of postnatal age (Fig. 2). Currents were small at 1 wk (Fig. 2A) and increased with age. Peak current (and current density: current/whole cell capacitance) increased significantly with age (Fig. 2, A and C). The biggest increase was seen from week 1 to week 2, and a plateau was approached by 3–5 wk. When currents were scaled to the same peak amplitude, the currents generally superimposed (Fig. 2B). With this protocol, a fast, transient component was evident in many cells at all ages (virtually all cells have an A-type current that is revealed with a recovery from inactivation protocol as in Fig. 5). The ratio of the transient current (peak current − current at 500 ms) to the persistent current (current at 500 ms) was unchanged with age (0.12 ± 0.08 at week 1, 0.13 ± 0.09 at week 2, 0.09 ± 0.06 at week 3, 0.11 ± 0.08 at week 4, and 0.11 ± 0.05 at 5 wk).

Fig. 2.

Changes in total outward current during postnatal development. A: examples of current recorded from a 1-wk-old animal and a 5-wk-old animal. Currents are shown at the same scale (inset on right). Note the A-type current in the 1-wk-old animal. B: same traces as in A, except scaled to the same peak amplitude. Except for the more rapid initial rise and early peak in the younger animal, the currents superimpose (suggesting no changes in kinetics of the persistent component). C: histogram for peak current density (current/Cm). *Significant difference from 1 wk; #significant difference from week 2. Number of cells: 1 wk, 20; 2 wk, 24; 3 wk, 32; 4 wk, 46; 5 wk, 21.

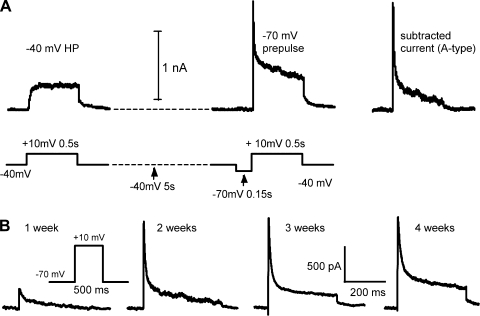

Fig. 5.

Changes in A-type current during postnatal development. A: A-type current was isolated by subtracting current from a holding potential (HP) of −40 mV from current elicited after a brief (150 ms) prepulse to −70 mV to remove inactivation of A-type current. The protocol (bottom trace) and resulting currents (top trace) are shown. Trace at right is the subtracted trace for this example. B: examples of subtracted currents recorded from animals at 1 wk, 2 wk, 3 wk, and 4 wk of age. Biophysical separation was incomplete, especially at the later ages (see text).

Development of Specific Current Components

Slowly inactivating currents.

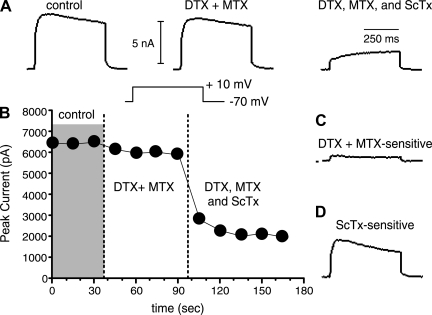

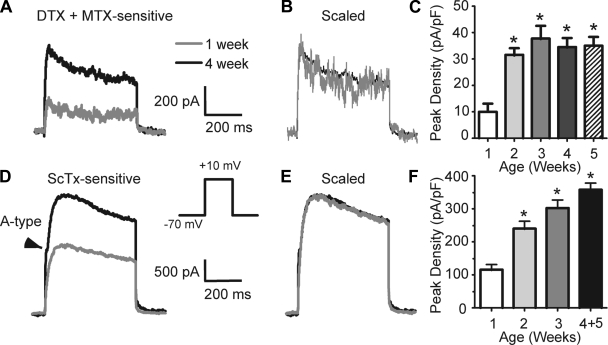

Previously, we demonstrated isolation of putative Kv1- and Kv2-mediated currents from 4- to 5-wk-old rats with specific toxins (Guan et al. 2006, 2007a, 2007b). We assume here that the sensitivities of specific potassium channels to the toxins do not change over the age range tested. Test steps to +10 mV (500 ms) from a HP of −70 mV were repeated every 15 s, and toxin-sensitive currents were determined as subtracted currents. We used DTX (100 nM) together with 10–30 nM MTX to block putative Kv1 channel currents and 600 nM ScTx to block the putative Kv2 channel currents (methods; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Pharmacological separation of slowly inactivating currents. A: representative traces (from a P23 animal) taken in control solution (left), after application of the Kv1 blockers 100 nM α-dendrotoxin (DTX) + 30 nM margatoxin (MTX) (center), and after subsequent application of the Kv2 blocker 600 nM Stromatoxin (ScTx) + DTX and MTX (right). Note that after the toxins a very slowly activating current remains. B: plot of peak current vs. time for the cell in A. Data were obtained from a holding potential of −70 mV. Voltage steps were to +10 mV. Currents were stable in control solution. DTX + MTX caused a small reduction in current. ScTx application blocked most of the remaining current. C: DTX+MTX-sensitive current (putative Kv1 mediated) obtained by subtraction of DTX+MTX trace in A from Control. In this cell there was a small transient and a larger persistent component to the putative Kv1-mediated current. D: ScTx-sensitive current (putative Kv2 mediated). This was the largest component in all cells.

Kv1 mediated.

Almost all cells at all ages expressed putative Kv1-mediated current (Fig. 4, Table 1). This current was very small at 1 wk and increased in amplitude with age (Fig. 4, A and C). This current made up 5–8% of the whole current at +10 mV, with no significant changes in this percentage with age (Table 1). Peak current and current density significantly increased during postnatal development (Fig. 4C; Table 1). Again, a large increase in amplitude occurred between weeks 1 and 2, with little change between weeks 3 and 5. At all ages, some cells expressed both transient and persistent components to the putative Kv1-mediated current. χ2-Analysis indicates that the percentage of cells with a transient component did not change with age (P = 0.71; week 1: 3/13 cells, week 2: 4/13 cells, week 3: 7/20 cells, week 4: 16/48 cells, week 5: 9/15 cells). When scaled to the same peak amplitude, currents from 1-wk and 5-wk cells superimposed (Fig. 4B), suggesting no changes in kinetics with age. Accordingly, we found no significant changes in the ratio of transient to persistent current, TTP, or activation time constant as a function of age (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Changes in putative Kv1- and Kv2-mediated current during postnatal development. A: examples of current sensitive to 100 nM DTX + 30 nM MTX from a 1-wk-old animal and a 4-wk-old animal. Currents are shown at the same scale (indicated on right). Note transient and persistent components at both ages. B: same traces as in A, except scaled to the same peak amplitude. The currents superimpose, suggesting similar kinetics at both ages. C: histogram for peak DTX- and MTX- sensitive current density (current/Cm) as a function of age. *Significant difference from 1 wk. Number of cells: 1 wk, 13; 2 wk, 13; 3 wk, 20; 4 wk, 38; 5 wk, 15. D–F: changes in putative Kv2-mediated outward current during postnatal development. D: examples of current sensitive to 600 nM ScTx recorded from a 1-wk-old animal (gray trace) and a 5-wk-old animal (black trace). Note A-type current sensitive to ScTx in this cell (arrowhead). Currents are shown at the same scale (indicated on right). E: same traces as in D, except scaled to the same peak amplitude. The currents superimpose, suggesting similar kinetics. F: histogram for peak density (current/Cm) of ScTx-sensitive current as a function of age. *Significant difference from 1 wk. Number of cells: 1 wk, 11; 2 wk, 13; 3 wk, 16; 4+5 wk combined, 16.

Table 1.

Putative Kv1 current as a function of age

| Age | Cm | Peak Amp | Density | SS Amp | SS Density | Peak % | SS % | TTP | τact | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | 13.9 ± 3.7 | 143 ± 170 | 10.1 ± 10.0 | 101 ± 116 | 7.2 ± 7.0 | 5.8 ± 5.2 | 4.8 ± 4.7 | 16.8 ± 8.2 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | 13 |

| Week 2 | 13.8 ± 3.0 | 423 ± 115* | 31.5 ± 8.6* | 293 ± 59* | 22.1 ± 6.1* | 8.8 ± 2.9 | 7.0 ± 2.4 | 29.4 ± 10.6 | 4.0 ± 2.1 | 13 |

| Week 3 | 13.4 ± 3.9 | 490 ± 275* | 37.0 ± 21.0* | 381 ± 237* | 28.6 ± 17.3* | 8.4 ± 3.8 | 6.8 ± 3.2 | 24.0 ± 16.0 | 3.9 ± 1.6 | 20 |

| Week 4 | 14.1 ± 3.5 | 460 ± 286* | 34.5 ± 22.6* | 368 ± 257* | 27.8 ± 20.1* | 8.3 ± 4.5 | 6.9 ± 4.3 | 23.1 ± 10.8 | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 38 |

| Week 5 | 13.9 ± 5.2 | 499 ± 286* | 35.1 ± 12.7* | 393 ± 282* | 28.4 ± 14.9* | 7.8 ± 2.9 | 6.2 ± 3.3 | 18.6 ± 4.1 | 4.3 ± 1.0 | 15 |

Values are means ± SD for n cells. Week 1 = 7 ± 3 days; week 2 = 14 ± 3 days; week 3 = 21 ± 3 days; week 4 = 28 ± 3 days; week 5 = 35 ± 3 days. α-Dendrotoxin (DTX, 100 nM)- and margatoxin (MTX, 20 nM)-sensitive current. Holding potential (HP) = −70 mV. Step to +10 mV. Cm, whole cell capacitance (pF); peak amp, peak amplitude of current (pA); density, peak amplitude of current/whole cell capacitance (pA/pF); SS amp, current at 500 ms after step onset (pA); SS density, current density at 500 ms after step onset/whole cell capacitance (pA/pF); peak %, (peak amplitude of DTX-sensitive/whole cell peak current) × 100; SS %, (amplitude of DTX-sensitive current at 500 ms/whole cell current at 500 ms) × 100; TTP, time to peak (ms); τact, activation time constant (ms). Fitting function = A[1 − exp(−t/τact)]2.

Significant difference from week 1.

Kv2 mediated.

All cells at all ages expressed a putative Kv2-mediated (ScTx sensitive) current (Fig. 4D; Table 2). This was the largest current component at all ages (Table 2). Similar to the putative Kv1-mediated component, putative Kv2-mediated current amplitude and density increased significantly from week 1 to week 2 and approached a plateau by 3–5 wk of age (Fig. 4F; Table 2). There were no changes in kinetics with age (Fig. 4E, Table 2). A transient A-type component was also observed in the ScTx-sensitive current (see below).

Table 2.

Putative Kv2 current as a function of age

| Age | Cm | Peak Amp | Density | SS Amp | SS Density | Peak % | SS % | TTP | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | 14.3 ± 3.8 | 1,633 ± 760† | 115 ± 54† | 1,408 ± 729† | 99 ± 54† | 59.1 ± 18.4 | 57.5 ± 18.9 | 166 ± 70 | 11 |

| Week 2 | 13.7 ± 3.7 | 3,224 ± 1,138* | 239 ± 82* | 2,579 ± 830* | 194 ± 73* | 60.7 ± 10.1 | 54.6 ± 10.4 | 142 ± 69 | 13 |

| Week 3 | 14.2 ± 3.7 | 4,090 ± 909* | 303 ± 93* | 3,242 ± 804* | 245 ± 88* | 61.1 ± 9.7 | 52.3 ± 12.1 | 156 ± 75 | 16 |

| Weeks 4–5 | 11.1 ± 2.2 | 3,989 ± 1,299* | 357 ± 82*† | 3,491 ± 1,136*† | 322 ± 84*† | 65.6 ± 5.9 | 58.7 ± 6.6 | 182 ± 43 | 16 |

Values are means ± SD for n cells. Week 1 = 7 ± 3 days; week 2 = 14 ± 3 days; week 3 = 21 ± 3 days; weeks 4–5 = 25–38 days combined. Stromatoxin (ScTx, 600 nM)-sensitive current. HP = −70 mV. Step to +10 mV. Cm, whole cell capacitance (pF); peak amp, peak amplitude of ScTx-sensitive current (pA); density, peak amplitude of ScTx-sensitive current/whole cell capacitance (pA/pF); SS amp, ScTx-sensitive current at 500 ms after step onset (pA); SS density, ScTx-sensitive current at 500 ms after step onset/whole cell capacitance (pA/pF); peak %, (peak amplitude of ScTx-sensitive current/whole peak current) × 100; SS %, (amplitude of ScTx-sensitive current at 500 ms/whole current at 500 ms) × 100; TTP, time to peak (ms).

Significant difference from week 1;

significant difference from week 2.

A-type current.

All of the data thus far were obtained in the presence of 100 μM Cd2+ to block Ca2+ currents and Ca2+-dependent currents. We previously reported negligible effects of 0.1 Cd2+ on the persistent components of the K+ current in these cells (Guan et al. 2007b); however, Cd2+ has been shown to shift the voltage dependence and kinetics of Kv currents (especially Kv4 mediated; Davidson and Kehl 1995; Follmer et al. 1992; Guan et al. 2007b; Wickenden et al. 1999). We tested the effects of 100 μM Cd2+ on A-type currents in five cells with a recovery from inactivation protocol (see below) and found that Cd2+ significantly reduced the peak A-type current at +10 mV (1,589 ± 371 vs. 467 ± 86 pA) and slowed the TTP (3.2 ± 0.3 vs. 7.8 ± 0.5 ms). Therefore, we performed a separate set of experiments, in the absence of Cd2+, to specifically study the development of A-type currents.

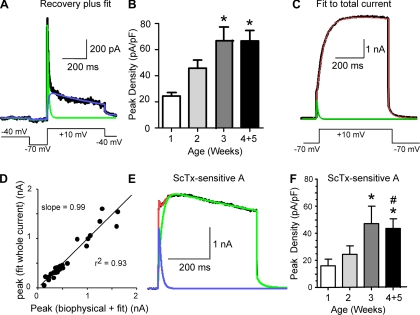

A-type current was first isolated with a biophysical approach that took advantage of differential kinetics of recovery from inactivation for A-type and persistent current components (Foehring and Surmeier 1993; Locke and Nerbonne 1997a, 1997b). The cells were held at −40 mV to inactivate most of the potassium currents. After an initial period at −40 mV to allow the holding current to stabilize, a two-pulse protocol was used to compare the currents in response to a step to +10 mV, with or without a 150-ms prepulse to −70 mV (to allow partial recovery of A-type current; see methods). This prepulse was well tolerated by all cells and is near the physiological resting potential. While only approximately half of the A-type current is recovered from inactivation at −70 mV (see below), this allowed us to compare many cells from animals of different ages using the same protocol. A-type current was defined by subtracting currents obtained without the prepulse from those obtained with the prepulse. This protocol was less effective at separating current in older animals, as evidenced by the persistent component in subtracted currents at 3–5 wk (Fig. 5B; see also Norris and Nerbonne 2010). The amplitude of A-type current isolated by recovery from inactivation increased with postnatal age (Fig. 5).

Because of the incomplete separation, we further isolated the A-type current by fitting the subtracted K+ currents using Eq. 1:

| (1) |

where IDR is the residual delayed rectifier component and IA is the A-type current. Kv1-mediated DR current was previously blocked by the presence of DTX and MTX. T1 and T2 are the activation and inactivation time constants of the DR component. T3 and T4 are the activation and inactivation time constants of the A-type current. An example of such a fit is seen in Fig. 6A. The data for biophysical isolation alone and biophysics plus subsequent fit are both included in Table 3. By either measurement, the amplitude of A-type current increased with postnatal age, with no significant changes in kinetics (TTP, activation tau, inactivation tau; Fig. 6B, Table 3). Currents were significantly smaller in the first week versus weeks 3–5 (Table 3). A plateau for current amplitude and density was observed at 3–5 wk (Fig. 6B; Table 3).

Fig. 6.

Separation of A-type current by biophysics (recovery from inactivation) + curve fitting or ScTx + curve fitting. A: traces from a pyramidal cell from a P28 animal. We isolated A-type current by a voltage protocol (inset, bottom), followed by further separation by fit to Eq. 1: I(t) = IDR(1 − e−t/T1)e−t/T2 + IA(1 − e−t/T3)4e−t/T4. The black trace is the original current trace, the green trace is the fitted A-type component, and the blue trace is the DR component. B: histogram for peak current density for the isolated A-type current as a function of age (current/Cm). *Significant difference from 1 wk. Number of cells: week 1, 10; week 2, 20; week 3, 12; weeks 4+5, 21. C: fit to whole current in response to step to +10 mV from −70 mV for the same cell as in A. The black trace is the whole current, the green trace is the fitted A-type component, and the red trace is the combined fit to the A-type and DR components. D: there was a significant correlation between the amplitude of A-type current isolated by curve fit from the whole current compared with biophysical separation (+ curve fit to remove residual DR). E: example of current sensitive to 600 nM ScTx in a pyramidal cell recorded from a p11 animal (black trace). The red trace represents the fit to the whole current using Eq. 1, the blue trace is the fit to the A-type component, and the green trace is the fit to the putative Kv2-mediated component (all data were obtained in the presence of DTX and MTX). F: histogram for density (peak I/Cm) of ScTx-sensitive A-type current (separated by fit to Eq. 1) as a function of age. *Significant difference from week 1; #significant difference from week 2. Number of cells: week 1, 9; week 2, 12; week 3, 11; weeks 4+5, 15.

Table 3.

A-type current as a function of age: comparison of A-type current isolated by subtraction (recovery from inactivation) or fit to whole current in the same cells

| Age | Cm | Peak Amp | Density | TTP | Fit Peak | TTP Fit | τact | τinact | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | 12.7 ± 2.0 | 322 ± 93 | 25.9 ± 8.0 | 3.2 ± 1.3 | 301 ± 86 | 3.0 ± 1.1 | 0.68 ± 0.32 | 18.6 ± 11.7 | 10 |

| Week 2 | 13.2 ± 3.2 | 637 ± 346 | 50.3 ± 29.4 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 568 ± 344 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 0.65 ± 0.18 | 10.0 ± 5.3 | 20 |

| Week 3 | 13.1 ± 5.8 | 1,020 ± 763* | 74.0 ± 34.7* | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 926 ± 711* | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 0.67 ± 0.11 | 15.6 ± 15.1 | 12 |

| Weeks 4–5 | 13.0 ± 3.6 | 971 ± 570* | 74.9 ± 40.4* | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 867 ± 535* | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 0.64 ± 0.12 | 15.1 ± 8.5 | 21 |

Values are means ± SD for n cells. Week 1 = 7 ± 3 days; week 2 = 14 ± 3 days; week 3 = 21 ± 3 days; weeks 4–5 = 25–38 days combined. Recordings were made in the absence of extracellular Cd2+. Step to +10 mV (recovery from inactivation protocol; see text). Cm, whole cell capacitance (pF); Peak Amp, peak amplitude of the subtracted A current (pA); density, peak amplitude of the A current/whole cell capacitance (pA/pF); TTP, time to peak for subtracted current (ms); Fit Peak, peak current determined by fit of Eq. 1 (pA); TTP fit, = TTP determined by fit of Eq. 1 (ms); τact, activation time constant (ms); τinact, inactivation time constant (ms). Data were obtained in the presence of 100 nM DTX and 30 nM MTX. This procedure removes residual DR current (after biophysical separation).

Significant difference from week 1.

As a further test of our fitting procedure, we used Eq. 1 to fit the total K+ current (unsubtracted; 20 cells) and compared estimates of A-type current determined from the fit to the total current (Fig. 6C) to that obtained by the combination of biophysical isolation and subsequent fit with Eq. 1 (Fig. 6A) in the same cells. The peak amplitudes were highly correlated (Fig. 6D; slope = 0.99, r2 = 0.93, P < 0.05, n = 28), as were the TTPs (r2 = 0.93, P < 0.05, n = 28), suggesting that both methods isolate the same A-type current component (Fig. 6D).

Isolation of A-Type Current by Fit to ScTx-Sensitive Current

ScTx has similar affinity for Kv2 subunits and Kv4 subunits (Escoubas et al. 2002). Thus in most cells the rising phase of the ScTx-sensitive outward current (tested in the presence of DTX, MTX, and 100 μM CdCl2) was steeper than expected for Kv2-mediated current alone (e.g., Fig. 6E). We therefore also examined A-type current separated by fitting Eq. 1 to the ScTx-sensitive current (Fig. 6E). In these cells, the activation-inactivation of ScTx-sensitive current was well fit with Eq. 1, where IDR is the Kv2-mediated persistent component and IA is the A-type current. These data are consistent with a significant fraction of the A-type current being due to Kv4 subunits in these cells (cf. Norris and Nerbonne 2010).

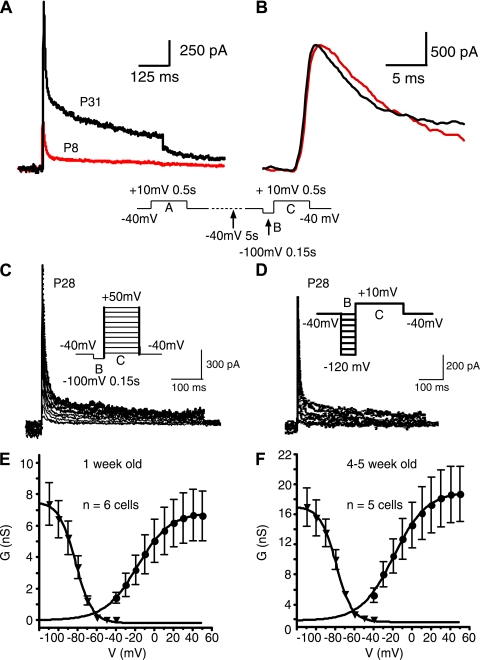

Kinetics and Voltage Dependence of A Current

To study the kinetics and voltage dependence of A-type current in more detail, we studied additional cells at 1 wk and 4–5 wk, using modifications to the recovery from inactivation protocol used in Figs. 5 and 6. These cells were examined in the absence of extracellular Cd2+ and in the presence of 30 mM TEA to block DR current. The cells were held at −40 mV to inactivate most of the potassium currents. We first used a two-pulse protocol to compare the currents in response to a step to +10 mV, with or without a 150 ms prepulse to −100 mV (to allow complete recovery of A-type current), followed by a 500-ms step to +10 mV (Fig. 7A, Table 4). At −100 mV, the recovery time constant was 36 ± 9 ms (n = 3). Compared with experiments with recovery at −70 mV, currents were significantly larger after a step to −100 mV (Tables 3 vs. 4). In these cells, there was a small but significant difference in the time constant for activation with age: younger cells had a longer τ (Fig. 7B, Table 4).

Fig. 7.

Activation and inactivation of A-type current at 1 wk and 4–5 wk of age. A: subtracted A-type current traces in the presence of 30 mM TEA (voltage protocol shown below traces). Black, cell from P31 animal; red, trace from P8 animal. B: expanded view of traces in A after normalization of peak current. Note slightly slower activation in P8 cell. C: steady-state activation. A family of subtracted traces is shown (obtained in 30 mM TEA). Protocol is identical to that in A and B except that the voltage was varied in 10-mV increments for the test pulse (step C in protocol). D: steady-state inactivation. A family of subtracted traces is shown (obtained in 30 mM TEA). Protocol is identical to that in A and B except that the recovery voltage was varied in 10 mV increments (step B in protocol). E: summary graphs for steady-state activation and inactivation for 1 wk-old animals (n = 6 cells for activation and 5 cells for inactivation). F: summary graphs for steady-state activation and inactivation for 4- to 5-wk-old animals (n = 5 cells). G, conductance; V, voltage.

Table 4.

A-type current as a function of age: isolation with TEA and recovery from inactivation at −100 mV

| Age, days | Cm | Peak Amp | Density | TTP | Fit Peak | TTP Fit | τact | τinact | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.4 ± 1.3 | 13.0 ± 4.4 | 929 ± 452 | 55.9 ± 17.1 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 649 ± 301 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 0.68 ± 0.13 | 8.9 ± 1.3 | 8 |

| 29.5 ± 2.2 | 11.9 ± 5.7 | 1,662 ± 813 | 146.9 ± 77.0 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 1,248 ± 504 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 0.57 ± 0.08* | 11.3 ± 0.4 | 7 |

Values are means ± SD for n cells. Week 1 = 7 ± 3 days; weeks 4–5 = 25–38 days combined. A-type current isolated by subtraction (recovery from inactivation). Recordings were made in the absence of extracellular Cd2+ and in the presence of 100 nM DTX, 30 nM MTX, and 30 mM TEA. Currents were elicited with a voltage step to +10 mV (recovery from inactivation protocol; see text). Cm, whole cell capacitance (pF); peak amp, peak amplitude of the A current (pA); density, peak amplitude of the A current/whole cell capacitance (pA/pF); TTP, time to peak (ms); fit peak, peak current determined by fit of Eq. 1 (pA) [this procedure removes residual DR current (after biophysical separation)]; TTP fit, TTP determined by fit of Eq. 1 (ms); τact, activation time constant (ms); τinact, inactivation time constant (ms)

Significant difference from week 1 (P < 0.05).

Steady-state activation was studied by varying the step after recovery (indicated by step C in protocol) at −100 mV to potentials between −40 mV and +50 mV (in 10-mV increments, Fig. 7C). Steady-state inactivation was studied by varying the recovery potential (indicated by step B in protocol) in 10-mV intervals between −110 mV and −40 mV (Fig. 7D). The resulting activation and inactivation curves are shown in Fig. 7E (1 wk) and Fig. 7F (4–5 wk). Half-activation voltages were −18 ± 1.0 mV at 1 wk and −19 ± 0.7 mV at 4 wk (corresponding slopes were 17 ± 0.3 and 17 ± 0.8 mV). The half-inactivation voltage was −82 ± 4.9 mV at 1 wk and −79 ± 2.5 mV at 4–5 wk (corresponding slopes were −8 ± 1.0 mV and −7.7 ± 0.8 mV). None of these values for half-activation or inactivation or slope differed significantly with age.

Immunocytochemistry

We compared cortex at 1 wk and 4–5 wk of age to test whether the developmental changes we observed for current components were accompanied by increased subunit protein expression. We found that Kv4.3 staining was found in the neuropil as well as somas and dendrites of pyramidal cells in all layers and that staining intensity was greater at 4–5 wk than in 1-wk-old postnatal animals (Fig. 8, A and B). In our hands, staining for Kv4.2 was not detectable at 1 wk and was weak but evident as diffuse staining throughout cortex at 4–5 wk (data not shown). These data suggest an increase in Kv4.3 (and Kv4.2) protein with postnatal age, consistent with our electrical data. A similar increase in staining was observed with Kv1.4 (Fig. 8C), which has also been shown to contribute to A-type current in neocortical pyramidal cells (Norris and Nerbonne 2010). We also saw increased Kv2.1 staining intensity with age, although the pattern of clustered channels on soma/proximal dendrite was evident by 1 wk (Fig. 8D).

Fig. 8.

Immunocytochemistry for Kv channels in rat somatosensory cortex during postnatal development. Higher-power images (B–D) were maximum-intensity projections from z-stacks containing the same number and thickness of optical sections for a given antibody. A: Kv4.3. A1: low-power view of stain for Kv4.3 at P9. A2: low-power view of Kv4.3 at P32. Note layer IV barrels (asterisks) and generally brighter staining in the older animal. Scale bar in A is 120 μm. B: Kv4.3: projections of 10 optical slices. B1: high-power view of layer III for Kv4.3 at P9. B2: Kv4.3 staining of layer III in a P32 animal. Note greater staining in the older animal. C: Kv1.4: projections of 13 optical slices. C1: high-power view (layer III) of Kv1.4 staining at P9. C2: Kv1.4 staining in a P32 animal. Note greater staining in the older animal. D: Kv2.1: projections of 12 optical slices. D1: high-power layer III staining in a P9 animal. D2: layer III staining in a P32 animal. The pattern of staining is similar at both ages. Staining intensity is greater in the older animal. Because the cellular detail in the 1 wk data was low, the brightness of the images for both ages in B1 and B2 were digitally brightened by 22%, images in C1 and C2 by 28%, and images in D1 and D2 by 22%. Scale bars for B–D are 20 μm.

DISCUSSION

Voltage-gated K+ currents increase in amplitude with age in neocortical pyramidal neurons (Bahrey and Moody 2003; Hamill et al. 1991; Picken Bahrey and Moody 2003; Zhou and Hablitz 1996a, 1996b); however, little is known about development of specific K+ current subtypes (defined by α-subunit family) or the biophysics of defined components during ontogeny. We characterized the expression of A-type current and specific Kv channel-mediated currents during postnatal development of acutely dissociated supragranular pyramidal neurons from rat somatosensory cortex.

Our data confirm that the total outward K+ current increases in amplitude and density over postnatal weeks 1–5. This increase was expressed to a similar degree by both transient A-type and persistent DR currents. Pharmacological analysis revealed that putative Kv1- and Kv2-mediated components increased in amplitude and density without major changes in kinetics. Most of the increase occurred between weeks 1 and 2, with a plateau at 3–5 wk of age. The A-type current was highly Cd2+ sensitive and ScTx sensitive, consistent with this component being primarily due to Kv4 α-subunits (Norris and Nerbonne 2010). As with the putative Kv1- and Kv2-mediated currents, the A-type current increased in amplitude with development. There was no significant change in inactivation kinetics with age, although we found a significantly longer activation time constant at 1 wk vs. 4–5 wk. Our qualitative immunochemical data were consistent with an increase in protein levels for Kv1.4, Kv2.1, Kv4.2, and Kv4.3 subunits between 1 wk and 4–5 wk of age. There were no significant changes in the relative proportions of any current component tested, suggesting a mature pattern by the end of week 1.

Our electrical data were obtained from acutely dissociated pyramidal cells from superficial layers of somatosensory cortex. The truncated processes of these cells facilitated spatial control of voltage but limit our conclusions to somatic and proximal dendritic membrane. Whole cell recordings are subject to washout of cellular constituents and run-down of currents during prolonged recordings, but our recordings were largely restricted to <10 min after break-in. Our findings are also dependent on the specificity of the pharmacological agents and antibodies used. We previously tested these pharmacological agents and found them to be selective at the doses used (Guan et al. 2006, 2007); however, this remains a concern. The monoclonal antibodies used were all reported not to stain cortex of knockout animals, suggesting their specificity (Burkhalter et al. 2006). Our voltage protocols for isolating A-type current are biased toward channel types with relatively rapid recovery from inactivation; thus our findings are likely biased toward detection of Kv4-mediated versus Kv1-mediated A-type current (which recovers much more slowly from inactivation; Bett and Rasmusson 2004).

Previous work showed that a persistent, DR current is present in neocortical neurons during early embryonic development and A-type current before E21 (Bahrey and Moody 2003; Mienville and Barker 1997). There is a subsequent postnatal increase in DR and A-type currents in pyramidal cells (Bahrey and Moody 2003; Hamill et al. 1991). In the first few postnatal days, the A-type current and the combined DR current increase with different developmental schedules (Bahrey and Moody 2003). Consistent with our electrophysiological and immunochemical data, Kv1.1 protein expression is present early in embryonic development, is low at birth, and rises dramatically at the end of the second postnatal week (P12–P15; Hallows and Tempel 1998). Similarly, Kv2.1 protein expression in cortex is present early in embryogenesis and gradually increases from birth until ∼P30 (Trimmer 1993). In layer V pyramidal neurons, Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 mRNA expression increases from P5–P7 to P28–P30 (Christophe et al. 2005).

The general pattern of increased K+ current density with development is also observed in other neuron types, for example, motoneurons (Martin-Caraballo and Greer 2000), CA1 pyramidal neurons (Falk et al. 2003; Spiegelman et al. 1992), Xenopus spinal neurons (Harris et al. 1988), cochlear nucleus pyramidal neurons (Bortone et al. 2006), and striatal medium spiny neurons (Surmeier et al. 1991). Unlike neocortical pyramidal cells, CA1 pyramidal cells and medium spiny cells exhibited a reduction in the ratio of A-type current to the persistent current with age (Spiegelman et al. 1992; Surmeier et al. 1991) that was associated with expression of a novel slowly inactivating current component after the first postnatal week (Surmeier et al. 1991). Our data indicate that any changes in relative expression of A-type versus DR current in neocortical pyramidal cells occur before the end of week 1.

In CA1 neurons (Spigelman et al. 1992) and motoneurons (Martin-Caraballo and Greer 2000) there were changes in voltage dependence and kinetics of the DR (and a Kv1-mediated component of A-type current in CA1 pyramids; Falk et al. 2003). In motoneurons, the A current has been reported to be large early and not increase with age (Gao and Ziskind-Conhaim, 1998) or to not increase with age (McCobb et al. 1990; Martin-Caraballo and Greer 2000).

Development of Excitability and Firing Patterns

It is difficult to evoke action potentials in embryonic cortical neurons, and little spontaneous activity is observed (Bahrey and Moody 2003; Crain 1952). With postnatal age, there is increased ability to spike, decreased AP threshold, increased AP amplitude, and decreased spike width (Bahrey and Moody 2003; Christophe et al. 2005; Kasper et al. 1994b; Kriegstein et al. 1987; Lorenzon and Foehring 1993; Maravall et al. 2004b; McCormick and Prince 1987; Metherate and Aramakis 1999; Oswald and Reyes 2008). Spontaneous firing also increases with development (Bahrey and Moody 2003). In neocortical pyramidal neurons, voltage-gated Na+ currents (Bahrey and Moody 2003; Huguenard et al. 1988), Ca2+ currents (Lorenzon and Foehring 1995), and IH (Bahrey and Moody 2003) also increase in density with development. Presumably, mature computational abilities of these cells require the postnatal increase of these inward currents, as well as Kv channels.

Consistent with our findings for Kv-mediated currents, the most dramatic changes in AP parameters occur between weeks 1 and 3, approaching adult values by weeks 3–5 (Lorenzon and Foehring 1993; McCormick and Prince 1987; Zhang 2004). Because of its relatively hyperpolarized activation range and fast kinetics (Foehring and Surmeier 1993; Yuan et al. 2005), the maturation of A-type current would be expected to lead to more rapid spike repolarization and narrower spikes. Lesser effects on spike parameters are expected for Kv1-mediated current (due to its small amplitude and slower kinetics; Bekkers and Delaney 2001; Guan et al. 2006, 2007a) or Kv2-mediated currents (depolarized activation range and slow kinetics; Guan et al. 2007b). However, Kv1-mediated currents contribute to spike threshold in mature pyramidal cells (Bekkers and Delaney 2001; Guan et al. 2007a).

Repetitive firing behavior also changes with age (Christophe et al. 2005; Kasper et al. 1994b; Lorenzon and Foehring 1993; Maravall et al. 2004b; McCormick and Prince 1987; Oswald and Reyes 2008). The greatest changes occur between weeks 1 and 3 (Bahrey and Moody 2003; Lorenzon and Foehring 1993; Locke and Nerbonne 1997a; Maravall et al. 2004b; Metherate and Aramakis 1999). Both Kv1 (Guan et al. 2006b)- and Kv2 (Foehring et al. 2009)-mediated currents regulate interspike intervals in these cells. McCormick and Prince (1987) proposed that conservation of the ratios between different types of K+ (and other) channel types allows for rhythmic, regular spiking in most pyramidal cells at all but the earliest postnatal ages. Consistent with this proposal, we found that the percentage of the current due to each Kv current remained stable with age.

Postnatal Development of Somatosensory Cortex

During the time when voltage-gated currents are increasing most rapidly (weeks 1–3), the rodent somatosensory system undergoes dramatic changes that fine-tune pyramidal cell intrinsic properties and connectivity. Active whisker exploration begins during postnatal week 2 (P11–P13; Landers and Ziegler 2006; Woolsey and Wann 1976) and is mature at the end of the third week. Synaptogenesis also peaks in the second postnatal week (Micheva and Beaulieu 1996), although the number of excitatory and inhibitory synapses increases until P32 (after which it declines; De Felipe et al. 1997). An adult-like EEG is first observed at ∼P10–P12 (Crain 1952; Snead and Stephens 1983). The reduced excitability of pyramidal cells in the first two postnatal weeks is correlated with immature K+ currents (present study; Lorenzon and Foehring 1993) and inward currents (Bahrey and Moody 2003; Huguenard et al. 1988; Lorenzon and Foehring 1995). These properties may limit pyramidal cell activity at ages prior to the mature expression of GABA-mediated synaptic inhibition, which begins at ∼P8 (Agmon and O'Dowd 1992). Interestingly, in Kv1.1 knockout mice, seizure susceptibility manifests at ∼2 wk of age (Rho et al. 1999). Several aspects of somatosensory cortical function exhibit plasticity and are sensitive to activity during critical periods of development (Feldman et al. 1999; Hentsch 2005). In particular, receptive field plasticity for L2/3 pyramidal cells is present until P10–P14 (Maravall et al. 2004a) and pyramidal cells undergo dendritic rearrangement in weeks 2–3 (Kasper et al. 1994a; Maravall et al. 2004a), becoming largely mature by about P21 (Blue and Parnevalas 1983; Kristt 1978; Miller 1981; Miller and Peters 1981; Wise and Jones 1976). These dendritic changes (Maravall et al. 2004a) and experience-dependent plasticity (Feldman et al. 1999; Hentsch 2005) are sensitive to levels and patterns of activity, which should in turn be affected by postsynaptic changes in somatic K+ currents.

GRANTS

The project described was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS-044163 (to R. C. Foehring).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Drs. Fu Ming Zhou and Matt Ennis for valuable comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Agmon and O'Dowd, 1992. Agmon A, O'Dowd DK. NMDA receptor-mediated currents are prominent in the thalamocortical synaptic response before maturation of inhibition. J Neurophysiol 68: 345–349, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahrey and Moody, 2003. Bahrey HL, Moody WJ. Voltage-gated currents, dye and electrical coupling in the embryonic mouse neocortex. Cereb Cortex 13: 239–251, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beique et al., 2004. Beique JC, Campbell B, Perring P, Hamblin MW, Walker P, Mladenovic L, Andrade R. Serotonergic regulation of membrane potential in developing rat prefrontal cortex: coordinated expression of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)1A, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT7 receptors. J Neurosci 24: 4807–4817, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers, 2000a. Bekkers JM. Properties of voltage-gated potassium currents in nucleated patches from large layer 5 cortical pyramidal neurons of the rat. J Physiol 525: 593–609, 2000a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers, 2000b. Bekkers JM. Distribution and activation of voltage-gated potassium channels in cell-attached and outside-out patches from large layer 5 cortical pyramidal neurons of the rat. J Physiol 525: 611–620, 2000b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers and Delaney, 2001. Bekkers JM, Delaney AJ. Modulation of excitability by alpha-dendrotoxin-sensitive potassium channels in neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 21: 6553–6560, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bett and Rasmusson, 2004. Bett GC, Rasmusson RL. Inactivation and recovery in Kv1.4 K+ channels: lipophilic interactions at the intracellular mouth of the pore. J Physiol 556: 109–120, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blue and Parnevalas, 1983. Blue ME, Parnevalas JG. The formation and maturation of synapses in the visual cortex of the rat. I. Qualitative analysis. J Neurocytol 12: 599–616, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortone et al., 2006. Bortone DS, Mitchell K, Manis PB. Developmental time course of potassium channel expression in the rat cochlear nucleus. Hear Res 211: 114–125, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhalter et al., 2006. Burkhalter A, Gonchar Y, Mellor RL, Nerbonne JM. Differential expression of IA channel subunits Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 in mouse visual cortical neurons and synapses. J Neurosci 26: 12274–12282, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caviness, 1982. Caviness VS., Jr Neocortical histogenesis in normal and reeler mice: a developmental study based upon [3H]thymidine autoradiography. Brain Res 256: 293–302, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caviness et al., 2009. Caviness VS, Jr, Nowakowski RS, Bhide PG. Neocortical electrogenesis: morphogenetic gradients and beyond. Trends Neurosci 32: 443–450, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophe et al., 2005. Christophe E, Doerflinger N, Lavery DJ, Molnár Z, Charpak S, Audinat E. Two populations of layer V pyramidal cells of the mouse neocortex: development and sensitivity to anesthetics. J Neurophysiol 94: 3357–3367, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain, 1952. Crain SM. Development of electrical activity in the cerebral cortex of the albino rat. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 81: 49–51, 1952 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crair and Malenka, 1995. Crair MC, Malenka RC. A critical period for long-term potentiation at thalamocortical synapses. Nature 375: 325–328, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson and Kehl, 1995. Davidson JL, Kehl SJ. Changes of activation and inactivation gating of the transient potassium current of rat pituitary melanotrophs caused by micromolar Cd2+ and Zn2+. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 73: 36–42, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felipe et al., 1997. De Felipe J, Marco P, Fairen A, Jones EG. Inhibitory synaptogenesis in mouse somatosensory cortex. Cereb Cortex 7: 619–634, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoubas et al., 2002. Escoubas P, Diochot S, Celerier ML, Nakajima T, Lazdunski M. Novel tarantula toxins for subtypes of voltage-dependent potassium channels in the Kv2 and Kv4 subfamilies. Mol Pharmacol 62: 48–57, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk et al., 2003. Falk T, Kilani RK, Strazdas LA, Borders RS, Steidl JV, Yool AJ, Sherman SJ. Developmental regulation of the A-type potassium-channel current in hippocampal neurons: role of the Kvbeta 1.1 subunit. Neuroscience 120: 387–404, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman et al., 1999. Feldman DE, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Synaptic plasticity at thalamocortical synapses in developing rat somatosensory cortex: LTP, LTD, and silent synapses. J Neurobiol 41: 92–101, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foehring and Surmeier, 1993. Foehring RC, Surmeier DJ. Voltage-gated potassium currents in acutely dissociated rat cortical neurons. J Neurophysiol 70: 51–63, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foehring et al., 2009. Foehring RC, Toleman T, Higgs M, Guan D, Spain WJ. Actions of Kv2.1 channels in rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. Soc Neurosci Abstr 34, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Follmer et al., 1992. Follmer CH, Lodge NJ, Cullinan CA, Colatsky TJ. Modulation of the delayed rectifier, IK, by cadmium in cat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 262: C75–C83, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, 1992. Fox K. A critical period for experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in rat barrel cortex. J Neurosci 12: 1826–1838, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, 1995. Fox K. The critical period for long-term potentiation in primary sensory cortex. Neuron 15: 485–488, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao and Ziskind-Conhaim, 1998. Gao BX, Ziskind-Conhaim Development of ionic currents underlying changes in action potential waveforms in rat spinal motoneurons. J Neurophysiol 80: 3047–3061, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Calvo et al., 1993. Garcia-Calvo M, Leonard RJ, Novick J, Stevens SP, Schmalhofer W, Kaczorowski GJ, Garcia ML. Purification, characterization, and biosynthesis of margatoxin, a component of Centuroides margaritus venom that selectively inhibits voltage-dependent potassium channels. J Biol Chem 268: 18866–18874, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan et al., 2005. Guan D, Armstrong WE, Tkatch T, Surmeier DJ, Foehring RC. Kv2 and Kv7 channels and the delayed rectifier current in neocortical pyramidal neurons. Soc Neurosci Abstr 31, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Guan et al., 2006. Guan D, Lee JC, Tkatch T, Surmeier DJ, Armstrong WE, Foehring RC. Expression and biophysical properties of Kv1 channels in supragranular neocortical pyramidal neurones. J Physiol 571: 371–389, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan et al., 2007a. Guan D, Lee JCF, Higgs M, Spain WJ, Armstrong WE, Foehring RC. Functional roles of Kv1 containing channels in neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol 97: 1931–1940, 2007a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan et al., 2007b. Guan D, Tkatch T, Surmeier DJ, Armstrong WE, Foehring RC. Kv2 subunits underlie slowly inactivating potassium current in rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Physiol 581: 941–60, 2007b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallows and Tempel, 1998. Hallows JL, Tempel BL. Expression of Kv1.1, a Shaker-like potassium channel, is temporally regulated in embryonic neurons and glia. J Neurosci 18: 5682–5691, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill et al., 1991. Hamill OP, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Patch-clamp studies of voltage-gated currents in identified neurons of the rat cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex 1: 48–61, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris et al., 1988. Harris GL, Henderson LP, Spitzer NC. Changes in densities and kinetics of delayed rectifier potassium channels during neuronal differentiation. Neuron 1: 739–750, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey and Robertson, 2004. Harvey AL, Robertson B. Dendrotoxins: structure-activity relationships and effects on potassium ion channels. Curr Med Chem 11: 3065–3077, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentsch, 2005. Hentsch TK. Critical period plasticity in local cortical circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci 6: 877–888, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs and Spain, 2009. Higgs MH, Spain WJ. Conditional bursting enhances resonant firing in neocortical layer 2–3 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 29: 1285–1299, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huguenard et al., 1988. Huguenard JR, Hamill OP, Prince DA. Developmental changes in Na+ conductances in rat neocortical neurons: appearance of a slowly inactivating component. J Neurophysiol 59: 778–795, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczorowski et al., 2007. Kaczorowski CC, Disterhoft J, Spruston N. Stability and plasticity of intrinsic membrane properties in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons: effects of internal anions. J Physiol 578: 799–818, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper et al., 1994a. Kasper EM, Lübke J, Larkman AU, Blakemore C. Pyramidal neurons in layer 5 of the rat visual cortex. III. Differential maturation of axon targeting, dendritic morphology, and electrophysiological properties. J Comp Neurol 339: 495–518, 1994a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper et al., 1994b. Kasper EM, Larkman AU, Lübke J, Blakemore C. Pyramidal neurons in layer 5 of the rat visual cortex. II. Development of electrophysiological properties. J Comp Neurol 339: 475–494, 1994b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korngreen and Sakmann, 2000. Korngreen A, Sakmann B. Voltage-gated K+ channels in layer 5 neocortical pyramidal neurones from young rats: subtypes and gradients. J Physiol 525: 621–639, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegstein et al., 1987. Kriegstein AR, Suppes T, Prince DA. Cellular and synaptic physiology and epileptogenesis of developing rat neocortical neurons in vitro. Brain Res 431: 161–171, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristt, 1978. Kristt DA. Neuronal differentiation in somatosensory cortex of the rat. I. Relationship to synaptogenesis in the first postnatal week. Brain Res 150: 467–486, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landers and Zeigler, 2006. Landers M, Zeigler PH. Development of rodent whisking: trigeminal input and central pattern generation. Somatosens Mot Res 23: 1–10, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke and Nerbonne, 1997a. Locke RE, Nerbonne JM. Role of voltage-gated K+ currents in mediating the regular-spiking phenotype of callosal-projecting rat visual cortical neurons. J Neurophysiol 78: 2321–2335, 1997a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke and Nerbonne, 1997b. Locke RE, Nerbonne JM. Three kinetically distinct Ca2+-independent depolarization-activated K+ currents in callosal-projecting rat visual cortical neurons. J Neurophysiol 78: 2309–2320, 1997b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzon and Foehring, 1993. Lorenzon NM, Foehring RC. The ontogeny of repetitive firing and its modulation by norepinephrine in rat neocortical neurons. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 73: 213–223, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzon and Foehring, 1995. Lorenzon NM, Foehring RC. Characterization of pharmacologically identified voltage-gated calcium channel currents in acutely isolated rat neocortical neurons. II. Postnatal development. J Neurophysiol 73: 1443–1451, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maravall et al., 2004a. Maravall M, Koh IY, Lindquist WB, Svoboda K. Experience-dependent changes in basal dendritic branching of layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons during a critical period for developmental plasticity in rat barrel cortex. Cereb Cortex 14: 655–664, 2004a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maravall et al., 2004b. Maravall M, Stern EA, Svoboda K. Development of intrinsic properties and excitability of layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons during a critical period for sensory maps in rat barrel cortex. J Neurophysiol 92: 144–156, 2004b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Caraballo and Greer, 2000. Martin-Caraballo M, Greer JJ. Development of potassium conductances in perinatal rat phrenic motoneurons. J Neurophysiol 83: 3497–3508, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Caraballo and Greer, 1999. Martin-Caraballo M, Greer JJ. Electrophysiological properties of rat phrenic motoneurons during perinatal development. J Neurophysiol 81: 1365–1378, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCobb et al., 1989. McCobb DP, Best PM, Beam KG. Development alters the expression of calcium currents in chick limb motoneurons. Neuron 2: 1633–1643, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCobb et al., 1990. McCobb DP, Best PM, Beam KG. The differentiation of excitability in embryonic chick limb motoneurons. J Neurosci 10: 2974–2984, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick and Prince, 1987. McCormick D, Prince DA. Post-natal development of electrophysiological properties of rat cerebral cortical pyramidal neurones. J Physiol 393: 743–762, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metherate and Aramakis, 1999. Metherate R, Aramakis VB. Intrinsic electrophysiology of neurons in thalamorecipient layers of developing rat auditory cortex. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 115: 131–144, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheva and Beaulieu, 1996. Micheva KD, Beaulieu C. Quantitative aspects of synaptogenesis in the rat barrel field cortex with special reference to GABA circuitry. J Comp Neurol 373: 340–354, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mienville and Barker, 1997. Mienville JM, Barker JL. Potassium current expression during prenatal corticogenesis in the rat. Neuroscience 81: 163–172, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, 1981. Miller M. Maturation of rat visual cortex. I. A quantitative study of Golgi-impregnated pyramidal neurons. J Neurocytol 10: 859–878, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller and Peters, 1981. Miller M, Peters A. Maturation of rat visual cortex. II. A combined Golgi-electron microscope study of pyramidal neurons. J Comp Neurol 203: 555–573, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerbonne et al., 2008. Nerbonne JM, Gerber BR, Norris A, Burkhalter A. Electrical remodelling maintains firing properties in cortical pyramidal neurons lacking KCND2-encoded A-type K+ currents. J Physiol 586: 1565–1579, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris and Nerbonne, 2010. Norris AJ, Nerbonne JM. Molecular dissection of IA in cortical pyramidal neurons reveals three distinct components encoded by Kv4.2, Kv4.3, and Kv1.4 alpha-subunits. J Neurosci 30: 5092–5101, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald and Reyes, 2008. Oswald AMM, Reyes AD. Maturation of intrinsic and synaptic properties of layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons in mouse auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol 99: 2998–3008, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picken Bahrey and Moody, 2003. Picken Bahrey HL, Moody WJ. Early development of voltage-gated ion currents and firing properties in neurons of the mouse cerebral cortex. J Neurophysiol 89: 1761–1773, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purpura et al., 1965. Purpura DP, Shofer RJ, Scarff T. Properties of synaptic activities and spike potentials of neurons in immature neocortex. J Neurophysiol 28: 925–942, 1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rho et al., 1999. Rho JM, Szot P, Tempel BL, Schwartzkroin PA. Developmental seizure susceptibility of Kv1.1 potassium channel knockout mice. Dev Neurosci 21: 320–327, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwindt et al., 1988. Schwindt PC, Spain WJ, Foehring RC, Stafstrom CE, Chubb MC, Crill WE. Multiple potassium conductances and their functions in neurons from cat sensorimotor cortex in vitro. J Neurophysiol 424–449, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd et al., 2003. Shepherd GMG, Pologruto TA, Svoboda K. Circuit analysis of experience-dependent plasticity in the developing rat barrel cortex. Neuron 38: 277–289, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snead and Stephens, 1983. Snead OC, 3rd, Stephens HI. Ontogeny of cortical and subcortical electroencephalographic events in unrestrained neonatal and infant rats. Exp Neurol 82: 249–269, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song et al., 1998. Song WJ, Tkatch T, Baranauskas G, Ichinohe N, Kitai ST, Surmeier DJ. Somatodendritic depolarization-activated potassium currents in rat neostriatal cholinergic interneurons are predominantly of the A type and attributable to coexpression of Kv4.2 and Kv4.1 subunits. J Neurosci 18: 3124–3137, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spigelman et al., 1992. Spigelman I, Zhang L, Carlen PL. Patch-clamp study of postnatal development of CA1 neurons in rat hippocampal slices: membrane excitability and K+ currents. J Neurophysiol 68: 55–69, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmeier et al., 1991. Surmeier DJ, Stefani A, Foehring RC, Kitai ST. Developmental regulation of a slowly-inactivating potassium conductance in rat neostriatal neurons. Neurosci Lett 122: 41–46, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern et al., 2001. Stern EA, Maravall M, Svoboda K. Rapid development and plasticity of layer 2/3 maps in rat barrel cortex in vivo. Neuron 31: 305–315, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi et al., 1994. Takahashi T, Nowakowski RS, Caviness VS., Jr Mode of cell proliferation in the developing mouse neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 375–379, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimmer, 1993. Trimmer JS. Expression of Kv2.1 delayed rectifier K+ channel isoforms in the developing rat brain. FEBS Lett 324: 205–210, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyzio et al., 2003. Tyzio R, Ivanov A, Bernard C, Holmes GL, Ben-Ari Y, Khazipov R. Membrane potential of CA3 hippocampal pyramidal cells during postnatal development. J Neurophysiol 90: 2964–2972, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Brederode et al., 2000. van Brederode JF, Foehring RC, Spain WJ. Morphological and electrophysiological properties of atypically oriented layer 2 pyramidal cells of the juvenile rat neocortex. Neuroscience 101: 851–861, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickenden et al., 1999. Wickenden AD, Tsushima RG, Losito VA, Kaprielian R, Backx PH. Effect of Cd2+ on Kv4.2 and Kv1.4 expressed in Xenopus oocytes and on the transient outward currents in rat and rabbit ventricular myocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem 9: 11–28, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise and Jones, 1976. Wise SP, Jones EG. The organization and postnatal development of the commissural projection of the rat somatic sensory cortex. J Comp Neurol 168: 313–343, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolsey and Wann, 1976. Woolsey TA, Wann JR. Areal changes in mouse cortical barrels following vibrissal damage at different postnatal ages. J Comp Neurol 170: 53–66, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan et al., 2005. Yuan W, Burkhalter A, Nerbonne JM. Functional role of the fast transient outward K+ current IA in pyramidal neurons in (rat) primary visual cortex. J Neurosci 25: 9185–9194, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, 2004. Zhang Z. Maturation of layer V pyramidal neurons in the rat prefrontal cortex: intrinsic properties and synaptic function. J Neurophysiol 91: 1171–1182, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou and Hablitz, 1996a. Zhou FM, Hablitz JJ. Postnatal development of membrane properties of layer I neurons in rat neocortex. J Neurosci 16: 1131–1139, 1996a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou and Hablitz, 1996b. Zhou FM, Hablitz JJ. Layer I neurons of the rat neocortex. II. Voltage-dependent outward currents. J Neurophysiol 76: 668–682, 1996b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]