Abstract

Etomidate is a widely used intravenous induction agent that is especially useful for patients at risk for hypotension during anesthesia induction. Side effects limiting its use include adrenocortical suppression, acidosis, myoclonus, venous irritation, and phlebitis. The osmolality of etomidate prepared in propylene glycol appears to play a crucial role in causing phlebitis. The increased use of etomidate during the recent propofol shortage correlated with an increase in reported incidences of postoperative phlebitis and thrombophlebitis at Ochsner Clinic Foundation from October 2009 through April 2010. Several methods aim to prevent such occurrences, including pretreatment with lidocaine (and possibly esmolol), lower doses of etomidate, and injection into larger veins. The most compelling evidence suggests that using a lipid formulation of etomidate instead of the traditional propylene glycol preparation may dramatically decrease venous sequelae.

Keywords: Etomidate, phlebitis, propofol shortage, thrombophlebitis

INTRODUCTION

Etomidate is an intravenous hypnotic agent developed to induce anesthesia. First used clinically in 1972,1 it has a rapid onset of action, exerts its action on the central nervous system primarily through gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors, and is associated with fast recovery based on rapid redistribution from the central compartment. A major advantage is etomidate's hemodynamic stability after an induction dose, making this induction drug particularly useful in patients with depressed cardiac function. Enthusiasm for its use has been limited because of side effects, including postoperative nausea and vomiting, myoclonus-associated myalgia,2 phlebitis, and, especially with continuous infusion, suppression of the pituitary-adrenocorticoid axis. Etomidate suppresses 11B-hydroxylase (an enzyme involved in the formation of cortisol).

The incidence of pain on injection of etomidate is reportedly as high as 81%.3 Etomidate is poorly water soluble and therefore formulated as a solution in 35% propylene glycol. This preparation of propylene glycol is analogous to an extremely hyperosmolar solution (4,900 mOsm/L)4,5 compared to normal serum osmolality (279-300 mOsm/L). Hyperosmolarity is thought to be the major contributing factor in pain on injection and venous irritation.4-6 There are reports of phlebitis and thrombophlebitis after injection with propylene glycol preparations of etomidate up to 7 days after surgery.4 Propylene glycol also limits etomidate's use as a continuous infusion because propylene glycol has been implicated in the development of acute renal failure and acidosis.7,8

CASE REPORTS

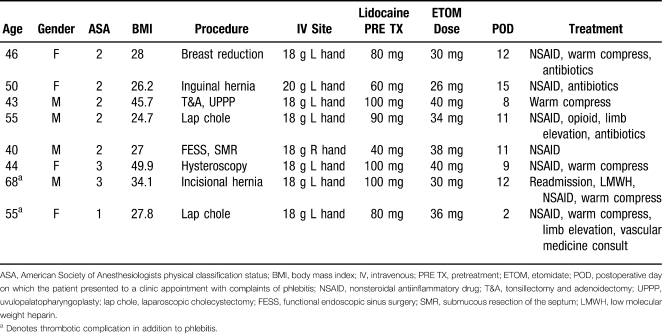

The use of etomidate increased significantly in our institution as a consequence of a national propofol shortage that lasted from October 2009 through April 2010. As a result, cases of postoperative phlebitis reported to our Department of Anesthesiology from individual surgery clinics increased. The cases were reported via our recently implemented electronic reporting system: Safety on Site. During the previous 12 months, no one reported a case of phlebitis or thrombophlebitis. Presented here are 8 cases of phlebitis after etomidate use as relayed by patients during postoperative follow-up appointments (Table 1). The phlebitis in all reported cases was close to the intravenous (IV) site.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 8 Patients With Phlebitis Following Etomidate

Only 4 surgery clinics reported these 8 cases (one surgeon's clinic reported 4 of them). This suggests that only certain clinics were reporting phlebitis to the Department of Anesthesiology. A more extensive chart review might reveal many more cases of phlebitis that had been treated but not reported.

DISCUSSION

Many patients experience pain on injection of etomidate during the induction of anesthesia, with an incidence of up to 81%.3 Postoperative phlebitis, especially thrombophlebitis, related to etomidate use is a substantive anesthetic complication that contributes to patient discomfort and cost of care if treatment is needed. The term phlebitis refers to the presence of inflammation within a vein, whereas thrombosis indicates the presence of clot. Treatment options for phlebitis and thrombophlebitis are limited and controversial.9 Traditionally, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and elastic stockings have been the primary treatments10; however, controlled clinical trials have not assessed the efficacy of these treatment modalities.9

In severe cases of thrombophlebitis, local thrombectomy can be performed. Other treatments available for superficial vein thrombosis include vein stripping and sclerotherapy, although these therapies are neither widely accepted nor without substantial risk.9 If a patient is known to be at risk for significant vein thrombosis (eg, hypercoagulable states, varicose veins), systemic anticoagulation may be warranted. Thrombophlebitis related to etomidate rarely requires such measures; however, anticoagulation may play an inadvertent role in prevention. Cardiovascular surgical procedures frequently necessitate heparin therapy as well as etomidate induction. This relationship may explain why, although etomidate is routinely used for these cases, we have not noted etomidate-related thrombophlebitis in this population at our institution. An informal survey of our cardiovascular anesthesiologists confirmed this perception. This discrepancy may be caused by differences in self-reporting in the general surgical and cardiovascular surgical populations. Substantiation of this hypothesis will require further study involving prospective data or a query of a large retrospective multicenter database such as the Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group (MPOG), both of which are beyond the scope of this article. More focused investigation may help delineate the mechanisms that cause phlebitis and the clinical scenarios most appropriate for etomidate use.

A more widely applicable method of prevention may be the use of an etomidate solution that does not contain propylene glycol. One such formulation mixes etomidate in a lipid emulsion of medium-chain and long-chain triglycerides. In at least 2 studies, the lipid emulsion formula was associated with significantly less pain on injection and significantly less phlebitis and thrombosis compared with etomidate in propylene glycol.6,11 Pain on injection associated with the lipid emulsion formula of etomidate was also studied in children.12 This study found that even propofol with added lidocaine had a significantly higher incidence of pain on injection compared to etomidate in lipid emulsion (47.5% compared to 5%, respectively). Unfortunately, no lipid emulsion formulation of etomidate is available for use in the United States, although it is readily available in some European countries.

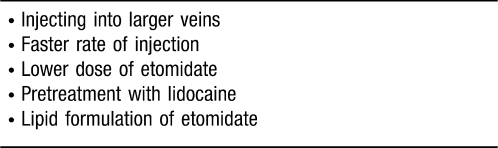

Although the availability of particular etomidate formulations may be limited, physicians have several other options for preventing pain on injection and phlebitis (Table 2). In one prospective study involving 161 patients, pretreatment with 20 mg of lidocaine reduced the incidence of painful injection by almost half.13 In the same study, patients who received lidocaine also had significantly less phlebitis than those who did not (7.4% vs 18%, respectively). All 8 patients in our case report received a pretreatment dose of lidocaine. A less traditional option for preventing pain on injection is the short-acting beta-antagonist esmolol. Compared to lidocaine, esmolol had a similar effect when given to prevent pain associated with rocuronium injection.14

Table 2.

Methods for Prevention of Painful Injection and Phlebitis

Another technique to prevent pain on injection and phlebitis is injecting into larger veins, typically in the antecubital fossa, in preference to veins in the dorsum of the hand.15 The rate of injection also influences the likelihood of pain on injection. In one study, reducing the injection time from 30 seconds to 15 seconds decreased the pain on injection from 27% to 14%, respectively.15 The dose of etomidate may also play a role in pain on injection, as larger doses are associated with a higher incidence of venous sequelae such as phlebitis and thrombophlebitis.15

Our study has several important limitations, the most significant of which is the variable nature of self-reporting by patients and surgical clinics via our hospital's quality surveillance system. Also significant is the retrospective nature of this study. Both of these aforementioned factors decreased the number of cases for analysis. Because of these limitations, meaningful conclusions would require multicenter participation such as the MPOG mentioned previously.

CONCLUSION

During the recent national propofol shortage, etomidate became a popular substitute for induction of anesthesia. As a result of this increase in etomidate usage, its venous sequelae were increasingly detected through the hospital's quality reporting system. A centralized database for adverse event reporting allowed practitioners to estimate the incidence of these side effects and helped them determine optimal substitutes during medication shortages. Of particular concern was the increase in reported incidence of postoperative phlebitis and thrombophlebitis. The mechanism of this venous irritation is closely associated with the hyperosmolar propylene glycol formulations of etomidate. Most cases of phlebitis are easily treated with a conservative approach (NSAIDs, warm compresses, etc). Treatment for more severe cases is not well studied. At least one of our reported cases required consultation of a vascular specialist, and another required readmission for anticoagulation therapy. Strategies for prevention include consideration for the site and technique of injection, pretreatment with lidocaine, using lower doses of etomidate, and using a lipid formulation of etomidate when available. Systemic anticoagulation during surgery following etomidate usage may attenuate the incidence of phlebitis.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial or proprietary interest in the subject matter of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Doenicke A. Clinical experimental studies and first report on clinical experience with a new IV hypnotic. 1973. pp. 22–25. Proceedings of the 6th International Refresher Course on Clinical Anesthesiology. Vienna, May 21-25.

- 2.Doenicke A. W., Roizen M. F., Kugler J., Kroll H., Foss J., Ostwald P. Reducing myoclonus after etomidate. Anesthesiology. 1999;90(1):113–119. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199901000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holdcroft A., Morgan M., Whitwam J. G., Lumley J. Effect of dose and premedication on induction complications with etomidate. Br J Anaesth. 1976;48(3):199–205. doi: 10.1093/bja/48.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doenicke A., Roizen M. F., Nebauer A. E., Kugler A., Hoernecke R., Beger-Hintzen H. A comparison of two formulations for etomidate, 2-hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin (HPCD) and propylene glycol. Anesth Analg. 1994;79(5):933–939. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199411000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doenicke A. W., Roizen M. F., Hoernecke R., Lorenz W., Ostwald P. Solvent for etomidate may cause pain and adverse effects. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83(3):464–466. doi: 10.1093/bja/83.3.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zacharias M., Clarke R. S., Dundee J. W., Johnston S. B. Venous sequelae following etomidate. Br J Anaesth. 1979;51(8):779–783. doi: 10.1093/bja/51.8.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedichek E., Kirschbaum B. A case of propylene glycol toxic reaction associated with etomidate infusion. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151(11):2297–2298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demey H. E., Daelemans R. A., Verpooten G. A., et al. Propylene glycol-induced side effects during intravenous nitroglycerin therapy. Intensive Care Med. 1988;14(3):221–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00717993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Decousus H., Epinat M., Guillot K., Quenet S., Boissier C., Tardy B. Superficial vein thrombosis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2003;9(5):393–397. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200309000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyers T. M., Agnelli G., Hull R. D., et al. Antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease. Chest. 2001;119((1 Suppl)):176S–193S. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.1_suppl.176s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doenicke A., Kugler A., Vollmann N., Suttmann H., Taeger K. [Etomidate using a new solubilizer. Experimental clinical studies on venous tolerance and bioavailability] Anaesthesist. 1990;39(10):475–480. German. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nyman Y., Von Hofsten K., Palm C., Eksborg S., Lönnqvist P. A. Etomidate-Lipuro is associated with considerably less injection pain in children compared with propofol with added lidocaine. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97(4):536–539. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rühmann I., Maier C. [The modification of injection pain and the incidence of thrombophlebitis following etomidate] Anasth Intensivther Notfallmed. 1990;25((Suppl 1)):31–33. German. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yavascaoglu B., Kaya F. N., Ozcan B. Esmolol pretreatment reduces the frequency and severity of pain on injection of rocuronium. J Clin Anesth. 2007;19(6):413–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganta R., Verma R. Pain on injection and venous sequelae following two formulations of etomidate. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1989;6(6):431–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]