Abstract

Do narcissists have insight into the negative aspects of their personality and reputation? Using both clinical and subclinical measures of narcissism, we examined others’ perceptions, self-perceptions and meta-perceptions of narcissists across a wide range of traits for a new acquaintance and close other (Study 1), longitudinally with a group of new acquaintances (Study 2), and among coworkers (Study 3). Results bring us to three surprising conclusions about narcissists: 1) they understand that others see them less positively than they see themselves (i.e., their meta-perceptions are less biased than are their self-perceptions), 2) they have some insight into the fact that they make positive first impressions that deteriorate over time, and 3) they have insight into their narcissistic personality (e.g., they describe themselves as arrogant). These findings shed light on some of the psychological mechanisms underlying narcissism.

Keywords: narcissism, meta-perception, interpersonal perception, personality

“Early in life I had to choose between honest arrogance and hypocritical humility. I chose honest arrogance and have seen no occasion to change” Frank Lloyd Wright

(quoted in the Michigan Daily, 1998)

Do narcissists have insight into the negative aspects of their personality and reputation? Lack of self-insight is believed to be a hallmark of narcissism, which suggests that narcissists should not have insight into the negative aspects of their personality or their reputation (e.g., arrogant, disagreeable, entitled). Indeed, narcissists see themselves very positively (e.g., Clifton, Turkheimer, & Oltmanns, 2004) and are motivated to maintain their overly positive self-perceptions (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001) which has led researchers to conclude that narcissists “…have less insight into their own condition” (Emmons, 1984, p. 297) and “…probably misunderstand how they are perceived” (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001, p.183). The main goal of this paper is to test these conclusions by empirically examining whether narcissists have insight into their personality, especially their narcissistic characteristics, and their reputation. Throughout the paper we take a dimensional approach to narcissism and use the term ‘narcissist’ to refer to people who score high on measures of clinical or subclinical narcissism (Miller & Campbell, 2010).

To assess the extent to which narcissists have insight into their personality and reputation, we conduct a multiple-perspective examination of how narcissists are seen by others (i.e., others’ perceptions), how they see themselves (i.e., self-perceptions), and how they believe they are seen by others (i.e., meta-perceptions). We also examine these multiple perspectives across several social contexts including new acquaintances, acquaintances not selected by the target (e.g., coworkers), and close others (e.g., friends and family). Thus, we provide a novel, comprehensive look at the interpersonal dynamics of narcissism through the eyes of a narcissist and through the eyes of those who interact with a narcissist.

Previous work has examined self-perceptions and others’ perceptions as psychological mechanisms underlying narcissism (e.g., Back, Egloff, & Schmukle, 2010; Buffardi & Campbell, 2008; Campbell, Bosson, Goheen, Lakey, & Kernis, 2007; Campbell & Campbell, 2009; Campbell, Rudich, & Sedikides, 2002; Farwell & Wohlwend-Lloyd, 1998; Konrath, Bushman, & Grove, 2009; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001; Paulhus, 1998; Raskin, Novacek, & Hogan, 1991; Rhodewalt & Eddings, 2002). However, virtually no attention has been paid to the potential role narcissists’ meta-perceptions, or the beliefs they have about how others see them, might play in this process. Meta-perceptions affect our self-perceptions, behavior, relationships, and well-being (Anderson, Srivastava, Beer, & Spataro, 2006; Leary, Haupt, Strausser & Chokel, 1988; Lemay & Dudley, 2009; Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 2000; Schlenker, 2003; Tice &Wallace, 2003). Given the key role meta-perceptions play in how we see ourselves and how we interact with others, some of the defining features of narcissism (e.g., overly positive self-perceptions, interpersonal problems) may be driven by how narcissists believe they are seen by others. In fact, one popular theory of narcissism argues that narcissists use others, through their meta-perceptions, to maintain their overly positive self-perceptions (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). However, we know of no research to date that has examined whether narcissists’ meta-perceptions of their personality are as positive as their self-perceptions. Learning how narcissists believe others perceive them will shed light on whether narcissists do in fact use meta-perceptions to maintain their overly positive self-perceptions or whether they find other ways to maintain their positive self-perceptions (e.g., derogate others). Below we outline two competing views about narcissists’ awareness of how they are seen by others.

Narcissists’ Self-Insight: Two Competing Views

Do narcissists realize that others do not share the glowing view they have of themselves? Do they know that they are narcissistic? The goal of this paper is to test two competing views about these questions. The first view, which we are calling the Narcissistic Ignorance view, argues that narcissists lack insight into their personality and reputation. That is, they fail to understand that they have narcissistic characteristics, and they overestimate how positively others see them (i.e., their meta-perceptions are just as overly positive as their self-perceptions). The second view, which we are calling the Narcissistic Awareness view, argues that narcissists have insight into their personality and reputation. That is, they understand that they have narcissistic characteristics, and their meta-perceptions are closer to others’ perceptions (i.e., less positively biased) than are their self-perceptions. For reasons discussed below, we predict that the Narcissistic Awareness view is correct.

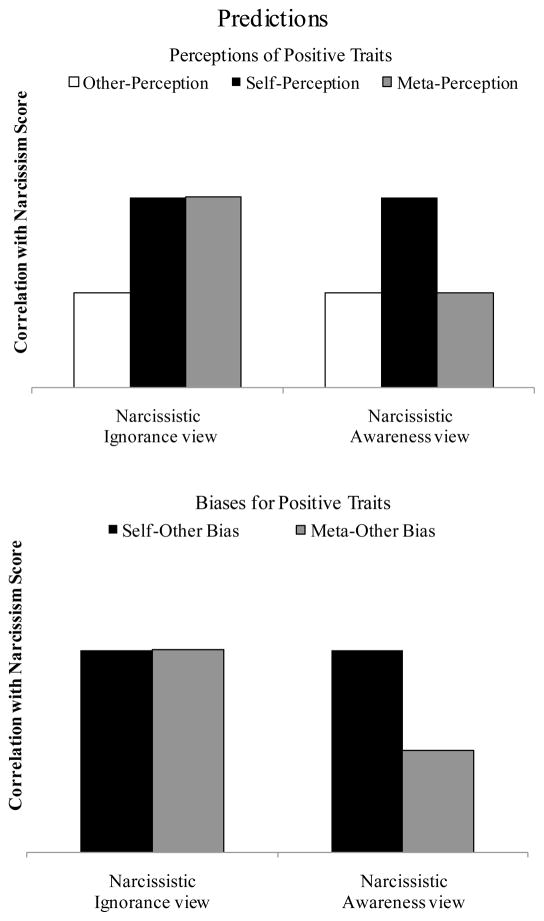

As shown in Figure 1, the two views make a few similar predictions. First, both views predict that narcissism will be strongly associated with positive self-perceptions. That is, we should observe a strong, positive correlation between narcissism scores and self-perceptions on positive traits (e.g., intelligence). Second, narcissists’ self-perceptions will be more positive than others’ perceptions. Specifically, narcissism should be positively associated with self-other bias (i.e., the difference score between self-perceptions and other-perceptions) for positive traits. Third, narcissism will be associated with having a narcissistic reputation. That is, we should observe a strong, positive correlation between narcissism scores and others’ perceptions of narcissistic traits. The critical difference between the two views is the predictions they make about narcissists’ meta-perceptions (i.e., their positivity and the degree to which they match up with others’ impressions) and whether they believe they are seen as narcissistic. Next, we outline four pairs of competing predictions that follow from the two views and provide our rationale for favoring the predictions made by the Narcissistic Awareness view.

Figure 1.

Two views about narcissists’ insight into their personality and reputation. The top panel reflects the predicted correlations between narcissism scores and perceptions (self-, meta-, and other-perceptions) of positive traits (e.g., intelligent). The middle panel reflects the predicted correlations between narcissism scores and self-other bias (positivity of self-perceptions relative to others’ perceptions) and meta-other bias (positivity of meta-perceptions relative to others’ perceptions) for positive traits. The bottom panel reflects the predicted correlations between narcissism scores and perceptions of narcissistic traits (e.g., arrogant).

Positivity of Self-Perceptions versus Meta-Perceptions

Narcissists are known for holding very positive self-views (e.g., Bleske-Rechek, Remiker, & Baker, 2008; Farwell & Wohlwend-Lloyd, 1998; Gabriel, Critelli, & Ee, 1994; Paulhus, 1998; Vazire & Funder, 2006). Morf and Rhodewalt’s (2001) dynamic self-regulatory processing model proposes that narcissists are motivated to maintain their positive self-perceptions and might do so by assuming that others see them in positive ways. For example, they might use self-presentational strategies to garner positive feedback or they may generally perceive feedback in positive ways. If narcissists’ positive self-perceptions are reinforced by their meta-perceptions, then narcissists should believe that they are seen just as positively by others as they see themselves. Narcissists do overestimate the desirability of their behavior suggesting that they probably also assume that others see them in positive ways (Gosling, John, Craik, & Robins, 1998). Thus, according to the Narcissistic Ignorance view, narcissists should believe that others see them just as positively as they see themselves and that narcissists use meta-perceptions to reinforce their positive self-perceptions.

In contrast, the Narcissistic Awareness view predicts that narcissists do understand that others see them differently than they see themselves. Evidence for this prediction comes from studies showing that narcissists are sensitive to negative feedback and tend to criticize such feedback (e.g., Horton & Sedikides, 2009; Kernis & Sun, 1994; Zeigler-Hill, Myers, & Clark, 2010). That is, they are likely aware that others do not always see them in positive ways. The strongest evidence for this prediction comes from recent empirical research that shows narcissists are able to acknowledge that others do not see their performance as positively as they see their own performance (Robins & Beer, 2001). That is, narcissists’ meta-perceptions of their performance were less positive than were their self-perceptions. Based on this evidence, we predict that, consistent with the Narcissistic Awareness view, narcissists can and do understand that their reputation is less positive than their self-perceptions and they maintain their positive self-perceptions in ways other than through meta-perceptions. These competing hypotheses are illustrated in the top panel of Figure 1.

Bias Relative to Others’ Perceptions

As discussed above, narcissists’ self-perceptions are positive. In fact, they are often more positive than others’ perceptions of them (e.g., Paulhus, 1998; Paulhus & John, 1998). Are their meta-perceptions just as positively biased relative to others’ impressions of them? As discussed above, the Narcissistic Ignorance view predicts that narcissists’ meta-perceptions are just as positive as are their self-perceptions. Thus, the Narcissistic Ignorance view also predicts that, relative to others’ perceptions of them, narcissists’ meta-perceptions are just as positively biased as are their self-perceptions.

In contrast, the Narcissistic Awareness view predicts that narcissists’ meta-perceptions are not as positively biased as are their self-perceptions, relative to others’ perceptions. As discussed above, recent empirical research suggests that narcissists are able to acknowledge that others do not see them as positively as they see themselves. Given that others generally do hold more negative perceptions of narcissists than narcissists hold of themselves, this leads to the prediction that narcissists’ meta-perceptions will be closer to others’ perceptions than are their self-perceptions. In other words, we predict that, consistent with the Narcissistic Awareness view, narcissists’ meta-perceptions will be less positively biased relative to others’ perceptions than are their self-perceptions. The competing hypotheses are presented in the middle panel of Figure 1.

Awareness of Changes in Others’ Perceptions

One fascinating aspect of narcissists is their ability to make a very positive first impression. At first sight, narcissists have a reputation for being charming, likeable, extraverted, open to experience, and physically attractive (Back et al., 2010; Friedman, Oltmanns, Gleason, & Turkheimer, 2006; Friedman, Oltmanns, & Turkheimer, 2007; Holtzman & Strube, 2010; Oltmanns, Friedman, Fiedler, & Turkheimer, 2004; Vazire, Naumann, Rentfrow, & Gosling, 2008). Even short, in-person interactions can result in positive impressions. For example, Paulhus (1998) found that after meeting narcissists for the first time, new acquaintances perceived them as high on all of the positive dimensions of the Big Five, as performing well on a group task, and as well- adjusted.

Although narcissists make a positive first impression, their reputation becomes much more negative as people get to know them. Paulhus (1998) also found that, although individuals scoring high on narcissism were initially seen positively, over several weeks narcissists developed a reputation for being especially disagreeable and relatively low on conscientiousness, emotional stability, openness, and adjustment. In sum, the reputation of a narcissist seems to depend on timing - narcissists make flattering first impressions that sour over time.

To our knowledge, no study has examined meta-perceptions of narcissists over time or across social contexts (e.g., meta-perceptions in first impression situations versus meta-perceptions for acquaintances), so the degree to which narcissists are aware of their changing reputation is unknown. One possibility is that, consistent with the Narcissistic Ignorance view, narcissists believe that they are seen positively across all contexts, from new acquaintances to close others. However, Back and his colleagues (2010) have pointed out that narcissists’ failure to pursue long-term relationships and friendships may reflect their awareness that only new acquaintances see them in a positive light. Thus, consistent with the Narcissistic Awareness view, we predict that narcissists do recognize that their reputation deteriorates over time. This argument hinges on the idea that narcissists are aware that they are seen more positively by new acquaintances than by people who know them well.

Awareness of Narcissistic Traits

Interestingly, others are able to detect narcissistic traits at above chance levels from minimal information (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008; Friedman et al., 2007; Vazire et al., 2008). But is the narcissist herself aware of this aspect of her personality? We know of only two studies examining this question, and the results are mixed. One study suggests that people who score higher on a subclinical measure of narcissism do not describe themselves as narcissistic (e.g., as selfish, egotistical, or conceited; Emmons, 1984), while another study suggests that narcissism, controlling for self-esteem, is associated with self-reports of experiencing hubristic pride (e.g., feeling smug; Tracy & Robins, 2007). Thus, at least for subclinical narcissism, the current evidence as to whether narcissists have insight into their narcissistic personality is unclear.

As mentioned above, lack of self-insight is considered to be a hallmark of narcissism, and some models of narcissism assume that narcissists do not fully appreciate how their behavior comes across to others (e.g., Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). Thus, it would be difficult for them to know that their behavior qualifies as arrogant or narcissistic. This line of argument suggests that, consistent with the Narcissistic Ignorance view, narcissists’ self- and meta-perceptions should not reflect an awareness of their narcissistic traits.

It is possible, however, that narcissists do understand that they are arrogant and narcissistic. Perhaps, as the opening quote attributed to Frank Lloyd Wright suggests, narcissists feel like they have earned the right to be arrogant and denying their arrogance would be insincere. Furthermore, it is possible that narcissists do not view narcissistic traits as negative, at least when they are backed up with actual superior qualities (e.g., they may view bragging as acceptable or even appealing, as long as it is true). In line with this, we predict that, consistent with the Narcissistic Awareness view, narcissists’ self- and meta-perceptions will reflect an awareness of their narcissistic traits. These competing hypotheses are presented in the bottom panel of Figure 1.

Overview of Studies

In three studies we examined narcissists’ insight into their personality and reputation. In each study, we administered a measure of narcissism to a non-clinical population and explored the relationship between narcissism scores and other-, self-, and meta-perceptions of several personality characteristics. Across the three studies, these characteristics included narcissistic traits (e.g., arrogant), positive traits that seem to be important to a narcissist’s self-concept (e.g., intelligent), and the Big Five traits. We also took a multiple-context approach by examining perceptions of narcissists in first impression situations, over the first few months of acquaintanceship, among coworkers, and among close others.

In addition to taking a multiple-perspective and multiple-context approach, we also captured a wide range of the narcissism spectrum by including multiple measures of narcissism. Some work suggests that subclinical and clinical measures of narcissism tap into different constructs (Miller & Campbell, 2008). Thus, we administered commonly-used subclinical measures in Studies 1 and 2 (the 40-item and 16-item Narcissistic Personality Inventory, NPI; Ames, Rose, & Anderson, 2006; Raskin & Terry, 1988) and a well-known clinical measure of narcissism in Study 3 (SIDP-IV; Pfohl, Blum, & Zimmerman, 1997).

Study 1

Participants in Study 1 completed a subclinical narcissism measure, described their own personality, and estimated the impressions they made on a new acquaintance and on people they know well from their everyday lives. Both new acquaintances and well-acquainted others provided their actual impressions of the participants which allowed us to compare narcissists’ self-perceptions and the impressions narcissists thought they made to the impressions they actually made on people from different social contexts.1

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 201; 71 men, 130 women; Mage = 19.5 years) were undergraduates at a private, Midwestern university who were given course credit for their participation. Approximately 63.2% were Caucasian, 20.8% were Asian American, 10.8% were African American or Black, 2.6% were Latin American, less than 1% were Native American or Middle Eastern, and about 1.3% described themselves as ‘other.’

Procedure

Participants took part in a first impression activity and a well-acquainted activity. The sample size was smaller for the first impression results (n = 176) than for the well-acquainted results (n = 201) because some participants were already acquainted with one another or one of the first impression partners did not attend the scheduled session.

Unacquainted participants came to the lab in pairs and completed a self-perception measure and a narcissism measure in separate rooms. Next, participants were briefly introduced to one another and instructed to get acquainted by talking about whatever topics they wished for five minutes.2 After the interaction, participants were taken back to their separate rooms where they provided perceptions of their partner’s personality (i.e., other-perceptions) and perceptions about how they thought their partner perceived their personality (i.e., meta-perceptions).

Next, in the well-acquainted activity, targets nominated three informants who knew them well. They provided meta-perceptions and email addresses for each informant. Within a few days, potential informants received an email that explained that the participant nominated them as someone who could describe his or her personality. The email requested that informants describe the participant’s personality using an online personality measure. Participants nominated 693 potential informants. Responding informants (N = 469, 67.7% response rate) were mostly friends (41.8%) and parents (23.9%); however, roommates (11.9%), romantic partners (8.3%), siblings (7.9%), and other informants (6.2%; e.g., cousin) also responded. Informants were not compensated for their participation (Vazire, 2006).

Measures

Others’ perceptions, self-perceptions, and meta-perceptions were measured using the same questionnaire; however, instructions were adapted for each type of perception. The questionnaire included the 44-item Big Five Inventory (BFI: John & Srivastava, 1999), a four-item measure of well-being (I see myself as someone who… “Is happy, satisfied with life”, “Has high self-esteem”, “Is depressed”, and “Is lonely”, with the latter two items reversed scored), and several other items (see Table 1). All items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 strongly disagree to 7 strongly agree).

Table 1.

Study 1: Descriptive Statistics for a First Impression and Close Other

| Self-Perception

|

First Impression

|

Close Other

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other-Perception

|

Meta-Perception

|

Other-Perception

|

Meta-Perception

|

|||||||

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SE) | Mean | (SE) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | |

| Extraverted | 4.64 | (1.10) | 4.37 | (0.10) | 5.01 | (0.08) | 5.04 | (1.09) | 5.00 | (1.09) |

| Agreeable | 5.14 | (0.90) | 5.27 | (0.06) | 5.13 | (0.06) | 5.51 | (1.11) | 5.11 | (0.97) |

| Conscientious | 4.77 | (0.97) | 4.91 | (0.06) | 4.58 | (0.06) | 5.26 | (1.05) | 4.76 | (1.03) |

| Emotionally Stable | 4.24 | (1.13) | 4.64 | (0.06) | 4.76 | (0.07) | 4.50 | (1.16) | 4.12 | (1.19) |

| Open | 5.03 | (0.93) | 4.74 | (0.07) | 4.51 | (0.06) | 5.12 | (1.03) | 5.10 | (0.94) |

| Well-Being | 5.30 | (1.11) | 5.38 | (0.07) | 5.57 | (0.07) | 5.48 | (1.14) | 5.32 | (1.11) |

| Intelligent | 5.69 | (0.91) | 5.77 | (0.07) | 5.18 | (0.08) | 6.55 | (0.66) | 6.11 | (0.85) |

| Physically Attractive | 4.98 | (1.17) | 4.66 | (0.11) | 4.75 | (0.08) | 6.04 | (1.18) | 5.70 | (1.14) |

| Honest | 5.77 | (1.03) | 5.60 | (0.07) | 5.43 | (0.07) | 6.16 | (1.02) | 5.94 | (1.08) |

| Likeable | 5.68 | (0.87) | 5.63 | (0.08) | 5.41 | (0.07) | 6.42 | (0.75) | 6.29 | (0.79) |

| Funny | 5.16 | (1.08) | 4.60 | (0.10) | 4.36 | (0.10) | 5.91 | (1.01) | 5.78 | (0.99) |

| Impulsive | 4.21 | (1.55) | 3.39 | (0.11) | 3.92 | (0.09) | 3.81 | (1.70) | 4.18 | (1.74) |

| Exaggerates Abilities | 3.57 | (1.53) | 2.97 | (0.11) | 3.48 | (0.11) | 2.51 | (1.47) | 3.41 | (1.64) |

| Arrogant | 3.01 | (1.55) | 2.41 | (0.10) | 3.50 | (0.13) | 2.21 | (1.41) | 3.10 | (1.65) |

| Power-Oriented | 4.22 | (1.56) | 3.85 | (0.10) | 4.12 | (0.10) | 4.44 | (1.69) | 4.29 | (1.74) |

Note. N = 88 dyads (i.e., N = 176 participants) for first impression ratings; N = 201 for close other ratings. Close other means are based on one randomly selected informant.

Others’ perceptions

Participants rated their interaction partner’s personality after reading the following prompt: “How do you think your partner typically thinks, feels, and behaves in everyday life? Please use the following items to rate your partner’s personality. This may or may not be the same as how he/she behaved in the interaction.” The average α internal consistency reliability for participants’ perceptions of one another on the Big Five and well-being scales was .87 and ranged from .82 for emotional stability to .92 for extraversion. Reliabilities for the single item measures (e.g., funny) were not assessed but were likely lower than the scale score measures.

Informants provided personality descriptions of the participant (referred to as X) after reading the following instructions: “The following statements concern your impression of X’s personality. Here are a number of behavioral characteristics that may or may not apply to X. For example, do you agree that X is someone who likes to spend time with others? Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree that the statement reflects X’s personality.” The average α internal consistency reliability on the Big Five and well-being scales was .87 and ranged from .86 for openness to .88 for extraversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability. Reliabilities for the single item measures were likely lower.

Self-perceptions

Participants described their own personality after reading the following instructions: “Here are a number of characteristics that may or may not apply to you. For example, do you agree that you are someone who likes to spend time with others?” The average α internal consistency reliability on the Big Five and well-being scales for self-perceptions was .85 and ranged from .81 for agreeableness to .90 for extraversion.

Meta-perceptions

Participants estimated the impression they made on each other after the getting acquainted interaction by responding to the following prompt: “How do you think your partner perceives your personality? Specifically, how do you think your partner perceives the way you typically think, feel, and behave in everyday life?” Similar instructions were provided when participants estimated how each of their informants viewed their personality. The average α internal consistency reliability on the Big Five and well-being scales of meta-perceptions for a new acquaintance was .87 and ranged from .81 for agreeableness to .92 for extraversion. The average reliability of meta-perceptions for informants was .86 and ranged from .85 for agreeableness to .88 for extraversion.

Narcissism

Participants completed the 16-item Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI-16; Ames et al., 2006), which is based on the full 40-item NPI (Raskin & Terry, 1988). Both are designed to assess the degree to which people exhibit a grandiose sense of self, feelings of entitlement, lack of empathy for others, and an exploitative interpersonal style. The α internal consistency reliability was .64, and the mean score was .33 (SD = .18) which is consistent with past findings (Ames et al., 2006).

Analyses

In the first impression activity, participants rated, and were rated by, their interaction partner; thus, the data were not independent. To account for nonindependence, the data were analyzed at the level of the dyad using multilevel modeling (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Dyad members were not distinguishable on any meaningful characteristic, thus they were treated as interchangeable. In addition, intercepts were allowed to vary randomly, but slopes were held constant across dyads (Kenny et al.). In the well-acquainted activity, participants provided meta-perceptions for, and were rated by, up to three informants. For the close other analyses presented below, we randomly selected one informant for each participant. All correlations mentioned in the text are significant unless otherwise noted (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Study 1: Correlations between the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI) and Others’ Perceptions, Self-Perceptions, Meta-Perceptions, and Bias Scores

| Correlations between Narcissism and Perceptions of Traits

|

Correlations between Narcissism and Bias Scores

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Impression

|

Close Other

|

First Impression

|

Close Other

|

||||||

| Self-Perception | Other-Perception | Meta-Perception | Other-Perception | Meta-Perception | Self-Other Bias | Meta-Other Bias | Self-Other Bias | Meta-Other Bias | |

| r | β | β | r | r | β | β | r | r | |

| Big Five Traits | |||||||||

| Extraverted | .43*** | .13† | .22** | .27*** | .30*** | .35*** | .16* | .34*** | .16* |

| Agreeable | −.25*** | −.08 | −.10 | −.20** | −.18** | −.19* | −.11 | −.18* | −.10 |

| Conscientious | .19** | .01 | .12 | .01 | .17* | .20** | .11 | .21** | .19** |

| Emotionally Stable | .16* | .11 | .16* | .09 | .09 | .22** | .17* | .14† | .05 |

| Open | .17* | .04 | .04 | .00 | .11 | .22** | .03 | .19** | .13† |

| Positive Traits | |||||||||

| Well-Being | .22** | .06 | .21** | .10 | .15* | .24** | .22** | .20** | .11 |

| Intelligent | .31*** | .13† | .11 | .01 | .13† | .27*** | .10 | .31*** | .14† |

| Physically Attractive | .39*** | .15* | .29*** | −.02 | .20** | .33*** | .26** | .41*** | .23** |

| Honest | .08 | −.01 | .01 | −.11 | −.02 | .08 | .01 | .09 | .01 |

| Likeable | .29*** | .13† | .12 | −.12† | .04 | .24** | .10 | .32*** | .08 |

| Funny | .25*** | .26** | .16* | −.04 | .25*** | .31*** | .13 | .28*** | .28*** |

| Narcissistic Traits | |||||||||

| Impulsive | .15* | .14† | .10 | .15* | .15* | .08 | .08 | .11 | .11 |

| Exaggerates Abilities | .19** | −.02 | .17* | .15* | .22** | .15* | .17* | .18* | .21** |

| Arrogant | .26*** | .02 | .20* | .26*** | .24** | .32*** | .19* | .21** | .17* |

| Power-Oriented | .38*** | .05 | .23** | .27*** | .31*** | .37*** | .23** | .34*** | .26*** |

Note.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

βs can be interpreted as correlations.

Results

Positivity of Self-Perceptions versus Meta-Perceptions

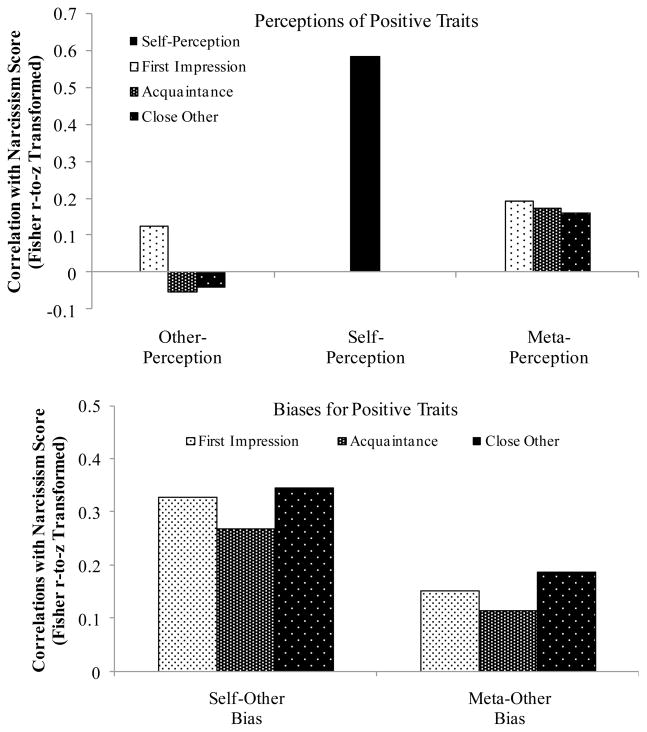

As predicted by both views, individuals scoring higher on narcissism saw themselves more positively (e.g., r = .25 for funny), especially on agentic traits such as extraversion (r = .43), intelligent (r = .31), and openness (r = .17) as well as physical attractiveness (r = .39). One critical test of our competing views was whether narcissism was also associated with positive meta-perceptions. In both contexts, narcissism was associated with positive meta-perceptions of extraversion (first impression β = .22; close other r = .30), physical attractiveness (first impression β = .29; close other r = .20), and funny (first impression β = .16; close other r = .25). However, consistent with our prediction and with the Narcissistic Awareness view, these effects were generally weaker than the associations between narcissism and positive self-perceptions. For example, for a new acquaintance, the correlation between narcissism and positive self-perceptions was stronger than the correlation between narcissism and positive meta-perceptions for the traits extraversion (t(85) = 1.71, p = .05), openness (t(85) = 2.08, p = .02), intelligence (t(85) = 1.47, p = .07), likeability (t(85) = 1.35, p = .09), and funny (t(85) = 1.62, p = .05).3 For close others, the correlation between narcissism and positive self-perceptions was stronger than the correlation between narcissism and positive meta-perceptions for the traits extraversion (t(198) = 3.48, p < .01), agreeableness (t(198) = −1.33, p = .09), emotional stability (t(198) = 1.47, p = .07), openness (t(198) = 4.74, p < .01), intelligence (t(198) = 2.18, p = .02), honesty (t(198) = 1.47, p = .07), likeability (t(198) = 3.46, p < .01), well-being (t(198) = 1.49, p = .07), and physical attractiveness (t(198) = 2.78, p < .01).

Bias Relative to Others’ Perceptions

To examine the extent to which narcissism is associated with bias, we used a procedure based on the self-criterion residual method (John & Robins, 1994; Paulhus & John, 1998). This procedure produces residual scores that reflect overestimation or underestimation of one perception relative to another. For example, when self-perceptions are regressed on others’ perceptions, the residuals reflect the degree to which self-perceptions are biased relative to others’ perceptions because all shared variance, or self-other agreement, has been removed. Thus, a positive residual reflects overly positive self-perceptions relative to others’ perceptions. These bias scores can be correlated with individual difference measures, such as narcissism scores, to examine whether narcissism is associated with reporting self-perceptions that are more positive or negative than others’ perceptions.

We examined two types of biases: 1) self-other bias, which is the degree to which people see themselves as higher or lower on a trait than others see them, and 2) meta-other bias, which is the degree to which people over- or under-estimate how others actually perceive them. These residuals or bias scores were correlated with participants’ NPI scores which allowed us to examine the degree to which narcissism was associated with biased self- and meta-perceptions relative to others’ perceptions. For example, a positive correlation between NPI scores and the self-other bias score for “likeable” would show that narcissism is associated with seeing the self as more likeable than others see the self, whereas a positive correlation between NPI scores and the meta-other bias score for “likeable” would show that narcissism is associated with believing that others see the self as more likeable than others actually do see the self.

As predicted by both views, narcissism was associated with reporting self-perceptions that were more positive than a new acquaintance’s and a close other’s perception, especially for agentic and positive traits such as extraversion (first impression r = .35, close other r = .34), intelligence (first impression r = .27, close other r = .31), and physical attractiveness (first impression r = .33, close other r = .41). In fact, narcissism was associated with self-other bias for every trait except for agreeableness, honesty, and impulsivity (see Table 2). Narcissism was also associated with meta-other bias for extraversion (new acquaintance r = .16, close other r = .16) and physical attractiveness (new acquaintance r = .26, close other r = .23).

Recall that the critical test of the two competing views is whether narcissism was as strongly associated with meta-other bias as it was with self-other bias. Consistent with the Narcissistic Awareness view, the overall correlation between narcissism and self-other bias was stronger than the correlation between narcissism and meta-other bias in a first impression (mean self-other bias r = .22; meta-other bias r = .12) and well-acquainted context (mean self-other bias r = .21; meta-other bias r = .14), although these overall differences did not reach statistical significance. The differences were significant for several positive and agentic traits. For a new acquaintance, the correlation between narcissism and self-other bias was significantly stronger than the correlation between narcissism and meta-other bias for the traits extraversion (t(85) = 1.84, p = .03), openness (t(85) = 2.02, p = .02), intelligence (t(85) = 1.45, p = .07), and funny (t(85) = 1.47, p = .07). Similarly, among close others, the correlation between narcissism and self-other bias was stronger than the correlation between narcissism and meta-other bias for the traits extraversion (t(198) = 3.38, p < .01), agreeableness (t(198) = −1.38, p < .08), emotional stability (t(198) = 1.50, p = .07), well-being (t(198) = 1.54, p = .06), intelligence (t(198) = 2.15, p = .02), physical attractiveness (t(198) = 2.54, p = .01), and likeability (t(198) = 3.16, p < .01). Consistent with our predictions, these results are most in line with the Narcissistic Awareness view which claims that narcissism should be strongly associated with a positive self-other bias, but not with a positive meta-other bias.

Awareness of Changes in Others’ Perceptions

Our results replicate previous findings that narcissists tend to make positive first impressions but are seen less positively by people who know them well. For instance, new acquaintances perceived individuals scoring higher on narcissism as more intelligent (β = .13), attractive (β = .15), and funny (β = .26), but close others did not see them as particularly intelligent (r = .01, n.s.), attractive (r = −.02, n.s.), or funny (r = −.04, n.s.). Moreover, new acquaintances perceived individuals scoring higher on narcissism as more likeable (β = .13), but close others perceived them as slightly less likeable (r = −.12) and less agreeable (r = −.20).

Were narcissists aware of their changing reputation? On one hand, narcissists correctly assumed that new acquaintances saw them positively (e.g., as more funny and attractive) and that close others saw them negatively (e.g., as narcissistic and less agreeable). On the other hand, they incorrectly assumed that close others perceived them in positive ways as well (e.g., as higher in well-being, as more conscientious, intelligent, funny and attractive; see Table 2). Thus, consistent with our predictions and with the Narcissistic Awareness view, narcissists were aware that close others saw them in more negative ways than new acquaintances. However, contrary to our predictions, narcissists seemed to have limited insight into the specific ways their reputation differed between new acquaintances and close others.

Awareness of Narcissistic Traits

As predicted by both views, narcissism was associated with having a narcissistic reputation. Specifically, close others perceived individuals scoring higher on narcissism as people who exaggerate their skills (r = .15) and value power more (r = .27) and as more arrogant (r = .26). However, consistent with our predictions and with the Narcissistic Awareness view, people who scored higher on narcissism also saw themselves as having more narcissistic qualities, specifically rating themselves as more arrogant (r = .26) and impulsive (r = .15) as well as someone who exaggerates skills more (r = .19) and values power in the self and others more (r = .38). Also consistent with the Narcissistic Awareness view, narcissism was positively associated with meta-perceptions for narcissistic traits in both contexts. That is, individuals scoring higher in narcissism believed that they were seen by others as more arrogant (first impression β = .20; close other r = .24), as someone who exaggerates abilities more (first impression β = .17; close other r = .22) and as someone who values power more (first impression β = .23; close other r = .31).

Discussion

As predicted by both views, narcissism was associated with holding positive self-perceptions and with being seen more positively by new acquaintances than by well-acquainted others. However, consistent with our predictions, the findings were closer to the Narcissistic Awareness view than to the Narcissistic Ignorance view. First, narcissists’ meta-perceptions for positive traits appeared to be less positive than their self-perceptions of those traits. Second, narcissism was more strongly associated with self-other bias than with meta-other bias for positive traits. Third, narcissists were somewhat aware that close others saw them in more negative ways than did new acquaintances. Fourth, narcissism was positively associated with self-perceptions and meta-perceptions of narcissistic traits, suggesting some insight into their narcissistic characteristics.

One limitation of Study 1 is that it provided a snapshot view of the acquaintanceship process by examining perceptions with a new acquaintance and with well-acquainted others. However, the differences between new acquaintances and close others might not accurately reflect the acquaintanceship process that occurs longitudinally. Moreover, close others were selected by the participants which might explain why narcissists’ meta-perceptions were fairly similar for a new acquaintance and a close other. Narcissists might understand that, in general, they make better impressions on new acquaintances than on people who know them well, but they may have selected their three informants specifically because they thought these close others, unlike most people who know them well, would provide positive ratings. The goal of Study 2 was to address these limitations by examining interpersonal perceptions among new acquaintances that were not selected by the target over the first few months of acquaintance.

Study 2

Study 2 was designed to assess whether narcissists understand that their reputation changes over time by examining the acquaintanceship process from the very first impression. Participants were undergraduates in a large personality class who were assigned to small groups at the beginning of the semester. Over the course of the semester, participants had brief discussions with their group members once a week, and during the first and last week, participants rated and were rated by their group members on several personality traits.

Method

Participants

Undergraduates (N = 110, 41 men, 69 women; Mage = 19.7 years) were students in a personality course at a private Midwestern university and participated in the current study as part of a class activity. Approximately 72% were Caucasian, 16% were Asian, 5% were African American, 5% were Latin American, and the rest of the students described their ethnicity as ‘other.’

Measures

Others’ perceptions, self-perceptions, and meta-perceptions were measured with the Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI; Gosling, Rentfrow, & Swann, 2003) and six additional traits (see Table 3). Instructions for each type of perception were: “How do you see Person X?” (other-perception), “How do you see yourself?” (self-perception), and “How does Person X see you?” (meta-perception). All perceptions were rated on a Likert-type scale from 1 (disagree strongly) to 15 (agree strongly). Although self-perception instructions were intended to measure general self-views, it is possible that participants rated themselves in the context of the group. Thus, we included self-perceptions from both time points. The average internal consistency reliabilities (i.e., αs) for the TIPI scale scores at Time 1 were .72 for other-perceptions, .59 for self-perceptions, and .53 for meta-perceptions. At Time 2, α reliabilities were .67 for other-perceptions, .69 for self-perceptions, and .52 for meta-perceptions. The TIPI scale scores tend to be relatively less reliable than longer measures of the Big Five (e.g., BFI) because the two- item scales reflect a wide range of the traits. That is, the scales were designed to demonstrate greater construct validity than reliability (Gosling et al.).

Table 3.

Study 2: Means for Others’ Perceptions, Self-Perceptions, and Meta-Perceptions at Time 1 and Time 2

| Time 1

|

Time 2

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other-Perception | Self-Perception | Meta-Perception | Other-Perception | Self-Perception | Meta-Perception | |

| Extraversion | 10.08 | 9.64 | 10.09 | 9.67 | 9.94 | 9.68 |

| Extraverted, enthusiastic | 10.65 | 10.54 | 10.46 | 10.58 | 10.72 | 9.42 |

| Reserved, quiet (r) | 9.50 | 8.74 | 9.72 | 9.35 | 9.15 | 9.94 |

| Agreeableness | 10.44 | 11.14 | 10.07 | 10.49 | 10.87 | 9.19 |

| Critical, quarrelsome (r) | 10.70 | 10.76 | 10.79 | 11.58 | 10.40 | 8.64 |

| Sympathetic, warm | 10.18 | 11.51 | 9.35 | 10.31 | 11.33 | 9.73 |

| Conscientiousness | 10.78 | 11.24 | 9.97 | 10.65 | 10.26 | 10.02 |

| Dependable, self-disciplined | 11.15 | 11.99 | 9.83 | 10.98 | 10.89 | 10.36 |

| Disorganized, careless (r) | 10.40 | 10.47 | 10.12 | 10.32 | 10.63 | 9.68 |

| Emotional Stability | 10.07 | 10.02 | 10.08 | 10.26 | 9.64 | 10.36 |

| Anxious, easily upset (r) | 9.72 | 9.50 | 10.05 | 10.88 | 8.97 | 10.46 |

| Calm, emotionally stable | 10.43 | 10.54 | 10.12 | 10.65 | 10.31 | 10.25 |

| Openness | 9.58 | 10.92 | 9.35 | 9.48 | 10.54 | 9.62 |

| Open to new experiences, complex | 10.09 | 11.58 | 9.72 | 10.02 | 11.04 | 9.75 |

| Conventional, uncreative (r) | 9.06 | 10.25 | 8.98 | 8.93 | 10.04 | 9.48 |

| Intelligent | 11.80 | 12.36 | 11.67 | 11.95 | 12.04 | 11.17 |

| Physically Attractive | 10.09 | 10.69 | 10.75 | 10.02 | 10.88 | 11.00 |

| Likeable | 11.56 | 11.76 | 10.58 | 11.45 | 11.92 | 11.75 |

| Funny | 8.64 | 10.50 | 6.42 | 8.88 | 10.58 | 8.42 |

| Exaggerates Abilities | 6.39 | 6.15 | 6.83 | 5.81 | 6.18 | 6.42 |

| Arrogant | 5.42 | 5.24 | 5.92 | 5.52 | 5.82 | 4.83 |

Note. Means are based on 19 groups. The TIPI Big Five scale scores as well as individual items within the scales are listed. (r) = reversed scored item.

Narcissism was measured with the 40-item NPI (Raskin & Terry, 1988). The α internal consistency reliability was .83 and the mean score was 16.20 (SD = 6.83).

Procedure

During the first week of class students were asked to find three or four students in the class they did not already know. These instructions generated 19 groups of three to five unacquainted students (Mgroup size = 3.7). Group members became acquainted over the course of the semester by taking part in brief discussions each week. For example, before the first rating activity, participants took part in the popular getting acquainted exercise where each person tells two truths and one lie, and everyone else attempts to detect the lie. After their discussion on the first and last week of class, students were asked to rate their own personality as well as each of their group members’ personalities and to provide meta-perceptions about each group member. Students also completed the NPI during the middle of the semester, along with other measures that are not relevant to the current study.4

Analyses

Each person rated, and was rated by, each group member, a procedure commonly referred to as a round robin design. To account for the interdependence among group members’ ratings, perceptions were analyzed using SOREMO (Kenny, 1992), a program designed for the analysis of round robin data based on the social relations model (Kenny, 1994). The analysis estimates the percentage of variance attributable to perceiver, target, and relationship effects and provides correlations among these effects and individual difference measures, such as narcissism. Similar to Study 1, we used NPI scores as the criterion for narcissism.

Results

Variance Partitioning

Perceiver (i.e., actor) and target (i.e., partner) variance for others’ perceptions was relatively equal across time points (mean perceiver variance at Time 1 = .28 and Time 2 = .27; mean target variance at Time 1 = .22 and Time 2 = .20). The strong target variance at Time 1 suggests that people reached consensus about their group members early on in the acquaintanceship process. Similar to past work (e.g., Kenny & DePaulo, 1993), meta-perceptions were characterized almost exclusively by perceiver variance (mean Time 1 = .81 and Time 2 = .51) and relationship variance (mean Time 1 = .16 and Time 2 = .41). The strong meta-perception perceiver variance suggests that there were strong individual differences in people’s beliefs about the impressions they made, and the strong relationship variance suggests that people believed that they made different impressions on each of their group members. For the most part, meta-perception target variance was weak (mean Time 1 = .02 and Time 2 = .09), suggesting that participants did not agree about how specific others formed impressions (i.e., they did not agree about which people were particularly harsh or lenient in their personality perceptions of others).

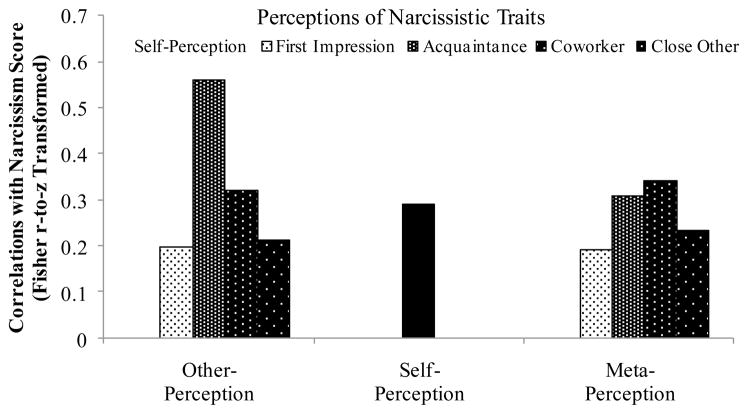

Positivity of Self-Perceptions versus Meta-Perceptions

As predicted by both views, individuals scoring higher on narcissism saw themselves positively (Table 4). Similar to Study 1, they perceived themselves as more agentic (i.e., extraverted r = .30 and open r = .31), intelligent (r = .31), likeable (r = .22), and physically attractive (r = .35). Narcissism was also associated with positive meta-perceptions (e.g., more extraverted r = .34, conscientious r = .21, and physically attractive r = .40). However, consistent with our prediction and with the Narcissistic Awareness view, the associations between narcissism and positive meta-perceptions were generally weaker than the associations between narcissism and positive self-perceptions. For example, at Time 1, narcissism was more strongly associated with positive self-perceptions than positive meta-perceptions for facets of extraversion (extraverted t(68) = 2.79, p < .01; reserved t(68) = 1.74, p = .04), agreeableness (sympathetic t(68) = 1.48, p = .07), openness (conventional t(68) = 1.43, p = .08), and funny (t(68) = 1.88, p = .03). At Time 2, narcissism was again more strongly associated with positive self-perceptions than with positive meta-perceptions for facets of agreeableness (critical t(68) = 3.74, p < .01) and openness (conventional t(68) = 1.31, p = .10) as well as funny (t(68) = 2.09, p = .02). The difference between the correlations was also significant for facets of emotional stability (anxious t(68) = 1.60, p = .06) and for intelligence (t(68) = 1.41, p = .08) and physical attractiveness (t(68) = 1.83, p = .04). Only facets of conscientiousness showed the opposite pattern where narcissism was more strongly associated with positive meta-perceptions than with positive self-perceptions (dependable Time 1 t(68) = −1.77, p = .04; Time 2 t(68) = −2.53, p < .01; Time 2 disorganized t(68) = −3.37, p < .01).

Table 4.

Study 2: Correlations between the NPI and Others’ Perceptions, Self-Perceptions, Meta-Perceptions and Bias Scores at Time 1 and Time 2

| Correlations between Narcissism and Perceptions of Traits

|

Correlations between Narcissism and Bias Scores

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 Perceptions

|

Time 2 Perceptions

|

Time 1 Biases

|

Time 2 Biases

|

|||||||

| Other-Perception | Self-Perception | Meta-Perception | Other-Perception | Self-Perception | Meta-Perception | Self-Other | Meta-Other | Self-Other | Meta-Other | |

| Big Five Traits | ||||||||||

| Extraversion | ||||||||||

| Extraverted, enthusiastic | .50* | .30* | .34* | .46* | .41* | .49* | .27 | −.01 | .25* | .12 |

| Reserved, quiet (r) | .65* | .40* | .29* | .52* | .51* | .69* | .16 | .02 | .31* | −.04 |

| Agreeableness | ||||||||||

| Critical, quarrelsome (r) | −.18 | −.01 | −.08 | −.44* | −.08 | −.91* | −.13 | −.13 | −.11 | −.53* |

| Sympathetic, warm | .01 | .03 | −.14 | −.17 | .19 | .27 | −.04 | −.19 | .11 | .24* |

| Conscientiousness | ||||||||||

| Dependable, self-disciplined | .12 | .17 | .21* | −1.0* | .06 | .54 | .08 | .11 | .03 | .15 |

| Disorganized, careless (r) | −.06 | −.09 | .04 | −.43* | −.04 | .34* | .04 | −.03 | −.08 | .19 |

| Emotional Stability | ||||||||||

| Anxious, easily upset (r) | .11 | −.17 | −.12 | −.13 | .21† | −.18 | .06 | −.16 | .14 | −.21† |

| Calm, emotionally stable | .01 | .06 | −.07 | −1.0 | .17 | −.17 | −.03 | −.05 | .11 | −.10 |

| Openness | ||||||||||

| Open to new experiences, complex | .63* | .31* | .19 | .06 | .23† | .13 | .31** | .01 | .21 | .01 |

| Conventional, uncreative (r) | .39 | .01 | .28 | .17 | .34* | .36* | .30** | .21† | .34** | .24* |

| Positive Traits | ||||||||||

| Intelligent | −.18 | .31* | .19 | −.65* | .28* | .06 | .29* | .15 | .09 | .05 |

| Physically Attractive | −.01 | .35* | .40* | .03 | .34* | .27* | .55* | .33* | .51* | .21† |

| Likeable | .19 | .22† | .16 | .07 | .31* | .18 | .34* | .04 | .27* | .11 |

| Funny | .32* | .09 | .05 | .43* | .30* | .17 | .14 | .07 | .14 | .08 |

| Narcissistic Traits | ||||||||||

| Exaggerates abilities | .61* | .29* | .19 | .63* | .40* | .31* | .25* | .05 | .34* | .24* |

| Arrogant | .35* | .34* | .27 | .36* | .37* | .29* | .36** | .21† | .38* | .29* |

Note.

p < .10;

p < .05.

N = 71. Individual TIPI items listed, (r) = reversed scored item.

Bias Relative to Others’ Perceptions

Similar to Study 1, we used the self-criterion residual method to compute self-other and meta-other bias scores. As predicted by both views, narcissism was associated with reporting self-perceptions that were more positive than others’ perceptions. Specifically, individuals scoring higher on narcissism perceived themselves as more agentic (i.e., extraverted Time 1 r = .27, open Time 2 r = .31), intelligent (Time 1 r = .29), attractive (Time 1 r = .55, Time 2 r = .51), and likeable (Time 1 r = .34, Time 2 r = .27) than peers perceived them, both initially and at the end of the semester (see Table 4). Narcissism was also associated with overestimating the positivity of one’s reputation (e.g., a strong correlation between meta-other bias for the trait physically attractive and facets of openness at both time points). However, consistent with our predictions and with the Narcissistic Awareness view, the correlations between narcissism and self-other bias were generally stronger than the correlations between narcissism and meta-other bias. Specifically, the association between narcissism and self-other bias was stronger at both times points (mean self-other bias at Time 1 r = .19; Time 2 r = .20) than the association between narcissism and meta-other bias (mean meta-other bias Time 1 r = .04; Time 2 r = .06), although this difference was not statistically significant. The correlation between narcissism scores and self-other bias was significantly stronger than the correlation between narcissism and meta-other bias for several positive traits such as likeability (Time 1 t(68) = 2.60, p = .01; Time 2 t(68) = 2.25, p = .01), physical attractiveness (Time 1 t(68) = 2.94, p < .01; Time 2 t(68) = 2.87, p < .01), intelligence (Time 1 t(68) = 1.29, p = .10), as well as facets of extraversion (reserved Time 2 t(68) = 2.51, p < .01), agreeableness (critical Time 2 t(68) = 4.53, p < .01), emotional stability (anxious Time 1 t(68) = 2.17, p = .02; Time 2 t(68) = 2.17, p = .02; calm Time 2 t(68) = 1.67, p = .05), and openness (open Time 1 t(68) = 2.10, p = .02;Time 2 t(68) = 1.43, p = .08). Only one trait showed a difference in the opposite direction where the correlation between narcissism and meta-other bias was stronger than the correlation between narcissism and self-other bias (disorganized Time 2 t(68) = −1.81, p = .04).

Awareness of Changes in Others’ Perceptions

As predicted by both views, individuals scoring higher in narcissism were perceived less positively over time. Table 4 shows that group members initially perceived people who scored higher on narcissism relatively positively (e.g., extraverted r = .50, open r =.63, and funny r = .32), but by the end of the semester, these people were seen as lower in agreeableness (r = −.44), conscientiousness (r = −.43), and intelligence (r = −.65).

Did individuals scoring higher in narcissism realize that their reputation became more negative over time? Initially, people scoring higher on narcissism believed they made positive first impressions and by the end of the semester, they still believed that they were seen more positively (i.e., as extraverted, conscientious, and physically attractive). However, they also believed that their group members perceived them as more arrogant (r = .29), as someone who exaggerates abilities more (r = .31), and as someone who is less agreeable (r = −.91). Thus, consistent with our predictions and with the Narcissistic Awareness view, individuals scoring higher on narcissism realized that their peers perceived them in more negative ways over time.

Awareness of Narcissistic Traits

People scoring higher on narcissism perceived themselves as more arrogant (r = .34) and as someone who exaggerates his or her abilities more (r = .29) and at Time 2 believed that their group members perceived them as more arrogant (r = .29) and as someone who exaggerates abilities more (r = .31). Thus, as we predicted and consistent with the Narcissistic Awareness view, individuals scoring higher on narcissism viewed themselves as narcissistic and realized that their peers perceived them as narcissistic as well.

Discussion

The current study replicated previous work showing that narcissists see themselves positively and make positive first impressions that become more negative over time (Paulhus, 1998). Moreover, these results replicate findings from Study 1 and provided more support for the Narcissistic Awareness view. First, narcissists’ meta-perceptions for positive traits appeared to be less positive than their self-perceptions. Second, narcissism was often more strongly associated with self-other bias than with meta-other bias, suggesting that when asked to guess how they are seen, narcissists’ meta-perceptions were closer to social reality than were their self-perceptions. Third, narcissists had some awareness that their reputation soured over time. That is, from Time 1 to Time 2, the associations between narcissism and meta-perceptions for positive traits became weaker while the associations between narcissism and meta-perceptions for narcissistic traits became stronger. Fourth, narcissism was positively associated with self-perceptions and meta-perceptions of narcissistic traits, suggesting that narcissists have some insight into their narcissistic characteristics. Taken together, these findings suggest that narcissists are aware that others do not see them as positively as they see themselves and that they have narcissistic qualities. Study 3 was designed to assess whether our findings extend to more pathological features of narcissism.

Study 3

Although people scoring higher on a subclinical measure of narcissism described themselves and their reputation as being narcissistic (Studies 1 and 2), people scoring higher on a clinical measure of narcissism arguably might not understand that others see them in negative ways or perceive themselves as having narcissistic traits. In Study 3, we administered a clinical measure of narcissism and examined others’ perceptions, self-perceptions, and meta-perceptions for narcissistic characteristics among well-acquainted peers (i.e., coworkers). Thus, the results obtained in the current study likely reflect tendencies of narcissists who exhibit the more pathological symptoms of narcissism.

Method

Participants

Participants in the current study were a subset (N = 274; 154 men, 120 women) of a larger sample (N = 2026) of Air Force recruits at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas described in previous reports (Oltmanns, Gleason, Klonsky, & Turkheimer, 2005). Participants were tested one day before the end of basic military training. Basic training lasted six weeks during which recruits lived and trained together in flights (groups) of 27–55 individuals (Mgroup size = 41.3). Most of the 49 flights that participated were mixed gender flights.

Procedure

Using a computer-based measure, participants were first asked to describe fellow flight members’ level of personality pathology by nominating specific flight members for each trait (see Oltmanns et al., 2005 for a detailed description of the nomination procedure). For each nomination, the judge was asked to indicate how much the target person exhibited that trait using a 0 to 3 scale (0 = never like this, 1 = sometimes like this, 2 = usually like this, and 3 = always like this). Other perception scores reflect the average number of nominations for a participant.

After participants completed the nomination procedure, they were asked to provide self- and meta-perceptions for the entire set of items by answering the following two questions using the same 0 to 3 response scale: (1) “How do you think most other people in your group rated you on this characteristic?” and (2) “What do you think you are really like on this characteristic? ”

Participants completed the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV; Pfohl et al., 1997), which investigates behaviors and experiences that correspond to diagnostic criteria for the 10 PDs listed in DSM-IV. The interview includes 101 questions and takes 45–90 minutes to administer. Each interview was scored by the interviewer and also subsequently watched and rated by another master’s level clinical psychologist to determine reliability. For each question, the interviewer assigned a score ranging from 0 (not present or limited to rare isolated examples) to 3 (strongly present – criterion is associated with subjective distress or some impairment in social or occupational functioning or intimate relationships). The mean reliability (i.e., intraclass correlations) for the continuous SIDP-IV PD scores was .80. The mean score on the narcissism subscale (i.e., mean of nine criteria) was 1.90 (SD = 2.56). Analyses are based on a continuous scoring of the SIDP narcissism subscale rather than a categorical measure of Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD). Moreover, our assessment of NPD was administered among a normal population, and results might not generalize to people who are above the clinical threshold for NPD.

Measures

Others’ perceptions, self-perceptions, and meta-perceptions were provided using the Multi-source Assessment of Personality Pathology (MAPP). The MAPP consists of 79 items based on the features of the 10 personality disorders identified in Diagnostic Statistical Manual (American Psychiatric Association, 2004) and 24 additional positively toned supplemental items. Each of the 78 criteria for personality disorders listed in DSM-IV was translated into a single question except for NPD criterion 8 which was split into two questions.

The α reliabilities for the narcissism MAPP subscales were .96 for the other-perception scale, .79 for the self-perception scale, and .86 for the meta-perception scale. The mean other perception score for the MAPP narcissism scale was .23 (mean number of nomination from peers; SD = .25), the mean self-perception score was 3.84 (SD = 4.49), and the mean meta-perception score was 4.84 (SD = 5.10).

Results

Participants’ SIDP narcissism scores were correlated with others’ perceptions, self-perceptions, and meta-perceptions for the MAPP narcissism scale and for each of the 78 MAPP items. The distribution of scores on the SIDP narcissism subscale was markedly, positively skewed, with many scores at the zero point. Thus, we used Spearman Rho correlations, which are similar to Pearson correlations in that they reflect the magnitude and direction of the association between the SIDP narcissism score and the perceptions of pathology.5

Awareness of Narcissistic Traits

The data from this study only allow us to test one of our predictions – narcissists’ awareness of their narcissistic traits. As predicted by both views, people scoring higher on the narcissism subscale of the SIPD were perceived as more narcissistic by their peers (r = .31). However, as we predicted and consistent with the Narcissistic Awareness view, people who scored higher on the SIDP narcissism subscale also perceived themselves as being more narcissistic (r = .29) and believed that others viewed them as more narcissistic (r = .33).

We also explored the relationship between the SIDP narcissism scores and others’ perceptions, self-perceptions, and meta-perceptions for each of the 78 MAPP items. Table 5 shows the ten strongest correlations between narcissism scores and others’ perceptions, self-perceptions, and meta-perceptions. These results revealed that some of the strongest correlations between narcissism scores and others’ perceptions were also the strongest correlations between narcissism scores and meta-perceptions (e.g., feels he or she deserves special favors or treatment). Thus, individuals higher in narcissism tended to agree with peers about the specific negative aspects of their personality.

Table 5.

Study 3: Strongest Ten Correlations between the SIDP Narcissism Scale and MAPP Items

| Other-Perceptions | Self-Perceptions | Meta-Perceptions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS1: Repeatedly gets in trouble with the police. | .31 | NA5: Feels he or she deserves special favors or treatment. | .31 | HS8: Considers his/her relationship with other people to be closer (more intimate) than they really are. | .30 |

| NA5: Feels he or she deserves special favors or treatment. | .31 | OC2: Needs to do such a perfect job that nothing ever gets finished. | .28 | ST7: Is odd or peculiar in behavior or appearance. | .28 |

| NA9: Is stuck up or “high and mighty.” | .31 | HS8: Considers his/her relationships with other people to be close (more intimate) than they really are. | .26 | OC2: Needs to do such a perfect job that nothing ever gets finished. | .27 |

| OC2: Needs to do such a perfect job that nothing ever gets finished. | .30 | NA7: Is not concerned about other people’s feelings or needs. | .25 | NA5: Feels he or she deserves special favors or treatment. | .26 |

| HS3: Has shallow emotions that change rapidly. | .30 | ST7: Is odd or peculiar in behavior or appearance. | .23 | NA6: Takes advantage of other people with no intention of paying them back. | .26 |

| NA6: Takes advantage of other people with no intention of paying them back. | .29 | ST2: Is superstitious or believes in mind-reading. | .23 | NA3: Thinks that he/she is special, so he/she should only hang out with other special people. | .25 |

| NA7: Is not concerned about other people’s feelings or needs. | .29 | NA3: Thinks that he/she is special, so he/she should only hang out with other special people. | .23 | NA7: Is not concerned about other people’s feelings or needs. | .24 |

| NA3: Thinks that he/she is special, so he/she should only hang out with other special people. | .28 | NA6: Takes advantage of other people with no intention of paying them back. | .22 | ST8: Has no close friends. | .23 |

| NA2: Spends too much time thinking about gaining unlimited success, power, or love. | .28 | BD3: Lacks fundamental sense of who he/she is. | .21 | BD3: Lacks fundamental sense of who he/she is. | .23 |

| NA1: Thinks he/she is much better than other people (without good reason). | .28 | NA4: Needs other people to admire him/her. | .21 | SZ6: Doesn’t care whether other people praise or criticize him/her. | .23 |

Note. All correlations are significant at p < .05. Bold items = narcissism was correlated with all three perceptions. Item codes: AS = Antisocial, BD = Borderline, HS = Histrionic, NA = Narcissism, OC = Obsessive Compulsive, ST = Schizotypal, SZ = Schizoid.

Discussion

As we predicted and consistent with the Narcissistic Awareness view, Study 3 showed that people who scored higher on a clinical measure of narcissism were more likely to describe themselves as narcissistic and to believe that peers perceived them as narcissistic as well. Moreover, people who scored higher on narcissism were more likely to describe themselves with some of the same specific features of narcissism that their peers used to describe them. Considering these findings with those from Studies 1 and 2, it appears that people high in subclinical narcissism and people high in clinical narcissism both understand that they have narcissistic traits and a narcissistic reputation.

General Discussion

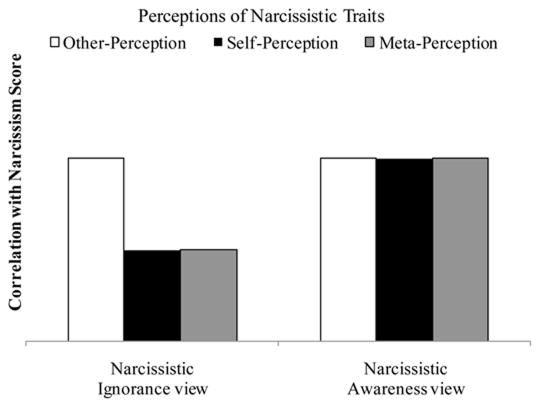

In three studies, we empirically examined whether narcissists have insight into their personality and reputation. Figure 2 depicts a meta-analytic summary of our findings across the three studies. Using Hedges’ fixed-effects model procedure (Field & Gillett, 2010), we computed the average correlations across our studies between narcissism scores and a) self-, meta-, and other-perceptions of positive traits, b) self-other and meta-other bias for positive traits, and c) self-, meta-, and other-perceptions of narcissistic traits (e.g., arrogance). Narcissism scores included subclinical (NPI-16 and the full NPI) and clinical (SIDP-IV narcissism subscale) measures of narcissism. Perceptions and biases of positive traits included the traits intelligent, physically attractive, likeable, and funny, and perceptions of narcissistic traits included the traits power-oriented, impulsive, arrogant, exaggerates abilities, and the MAPP narcissism scale.

Figure 2.

A mini meta-analysis of results across three studies. The top panel reflects the average correlations between narcissism scores and perceptions (self-, meta-, and other-perceptions) of positive traits (e.g., intelligent). The middle panel reflects the average correlations between narcissism scores and self-other bias (positivity of self-perceptions relative to others’ perceptions) and meta-other bias (positivity of meta-perceptions relative to others’ perceptions) for positive traits. The bottom panel reflects the average correlations between narcissism scores and perceptions of narcissistic traits (e.g., arrogant).

The Narcissistic Ignorance View and the Narcissistic Awareness view make three similar predictions. As shown in Figure 2, each prediction was borne out by the data: a) there was a strong positive correlation between narcissism and self-perceptions for positive traits but a weak negative correlation between narcissism and others’ perceptions for positive traits, b) there was a strong positive correlation between narcissism and self-other bias, and c) there was a strong positive correlation between narcissism and having a reputation for narcissism.

The key differences between the two views are the predictions they make about the positivity and bias of narcissists’ meta-perceptions and about narcissists’ perceptions of their narcissistic characteristics. Recall that we predicted that there would be more support for the Narcissistic Awareness view than the Narcissistic Ignorance view. As shown in Figure 2, results from the three studies did in fact provide the most support for the predictions outlined by the Narcissistic Awareness view. First, the association between narcissism and self-perceptions of positive traits was stronger than the association between narcissism and meta-perceptions of positive traits. Thus, even on traits that are important to a narcissist’s self-concept, such as intelligence, narcissists did not assume that others saw them as positively as they saw themselves. Second, narcissists’ meta-perceptions of positive traits were generally closer to how they were actually seen by others than were their self-perceptions (i.e., the correlation between narcissism and self-other bias was stronger than the correlation between narcissism and meta-other bias). Third, the correlation between narcissism scores and self- and meta-perceptions of narcissistic traits were strong and close to the correlation between narcissism scores and others’ perceptions of narcissistic traits. Thus, narcissists seem to be aware that they have a narcissistic personality and reputation.

In sum, our findings suggest three general conclusions about narcissism. First, narcissists understand that others do not see them as positively as they see themselves. Second, they understand that their reputation is more positive in a first impression context than among people who know them well. Third, narcissists describe themselves and their reputation as narcissistic.

Implications of the Narcissistic Awareness View

Our findings have implications for the psychological mechanisms underlying narcissism. Specifically, the fact that narcissists seem to be aware that they have a narcissistic personality and that others see them less positively than they see themselves might shed light on how they maintain their overly positive self-perceptions, why they tend to engage in maladaptive behaviors (e.g., bragging) and relationship patterns, and why they experience psychological distress in interpersonal domains.

Overly positive self-perceptions

Narcissists’ meta-perceptions are less positive than their self-perceptions, suggesting that they maintain overly positive self-perceptions by means other than meta-perception. Narcissists tend to derogate any source of negative feedback, and they can be especially harsh judges of others’ personalities (Horton & Sedikides, 2009; Kernis & Sun, 1994; Wood, Harms, & Vazire, 2010). Thus, one way narcissists might maintain their overly positive self-perceptions is by assuming that others are too dim to recognize their brilliance. Similarly, narcissists might even boost their self-perceptions from negative meta-perceptions by assuming that others see them less positively because they are jealous of them.

Narcissists also describe themselves and their reputation as narcissistic. How can they maintain their overly positive self-perceptions on positive traits while also perceiving themselves as narcissistic? On one hand, narcissists might endorse narcissistic items such as “arrogant” because they do not understand that these traits reflect negative characteristics. For example, when the typical person reads the item “arrogant,” he probably thinks of someone who is confident without merit. In contrast, when a narcissist reads the same item, she might believe that the trait refers to someone who is criticized by others for being, like Frank Lloyd Wright, rightfully confident. Similarly, narcissists might perceive narcissistic traits as being desirable. For example, they may associate narcissism with respect or status. One consistent finding in the narcissism literature is that narcissists see themselves as being intelligent, extraverted, and open to experience, but not necessarily as agreeable or moral (Campbell et al., 2002). That is, narcissists seem to see themselves more positively on agentic traits than on communal traits (Bradlee & Emmons, 1992), which is consistent with the theory that narcissists would rather be admired than liked (Raskin et al., 1991). Some of our findings are consistent with the possibility that narcissists believe that narcissistic traits are positive. In Study 1, the only traits that did not show a correlation between narcissism and self-other bias were communal traits such as agreeableness and honesty. However, narcissism was strongly associated with self-other bias for agentic and narcissistic traits, suggesting that perhaps narcissists view narcissistic traits as agentic instead of negative.

On the other hand, narcissists might fully understand the meaning of narcissistic traits and understand the negative impact these traits have on others. This might explain why narcissists suffer from psychological distress (i.e., anxiety and depression), particularly in interpersonal domains (Miller, Campbell, & Pilkonis, 2007). Hopefully, future research will disentangle the meaning narcissists assign to narcissistic traits. Such an investigation would help determine whether narcissists’ agreement with others about their narcissistic characteristics reflects a genuine understanding of the effect they have on others or whether their agreement is due to their misunderstanding (or idiosyncratic understanding) of narcissistic traits.

Interpersonal Style

It appears that narcissists believe that others do not see them as positively as they see themselves. For example, from the perspective of narcissists, others fail to perceive the full magnitude of their likeability, intelligence, and attractiveness. The discrepancy between their self-perceptions and their meta-perceptions might explain why narcissists behave in arrogant ways (e.g., brag). Specifically, they may be seeking the recognition they believe they deserve. This would be consistent with self-verification theory (North & Swann, 2009), which argues that people are uncomfortable when they believe that others do not see them as they see themselves and try to bring others to see them as they see themselves. Unlike people with more realistic self-perceptions, narcissists’ self-perceptions are so unrealistically positive that others rarely do see them as they see themselves. Thus, narcissists believe that they are exceptional people and may behave in arrogant ways because they are attempting to bridge the gap between their self-perceptions and their meta-perceptions.

Relationship Patterns

Narcissists seem to have considerable difficulty in forging long-term relationships (Back et al., 2010; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). One explanation might be that narcissists believe they are ‘too good’ for most people and discontinue relationships to seek out better friends or relationship partners (Campbell, 1999; Campbell & Foster, 2002). However, others have argued that the positive impressions narcissists make on new acquaintances likely make first impression contexts more rewarding for narcissists than well-acquainted contexts (Back et al., 2010). Our findings suggest that new acquaintances view narcissists more positively than well-acquainted others and that narcissists recognize that they are seen more positively by new acquaintances than by close others. Consistent with self-verification theory and with Back and colleagues’ hypothesis, it is possible that narcissists discontinue relationships early on because they cannot bridge the gap between their positive self-perceptions and relatively negative meta-perceptions. We hope that future research will identify which factors are responsible for changes in perceptions across the acquaintanceship process. Do narcissists behave in more narcissistic ways over time or do others simply notice (too late) that a narcissist was not a good friend all along?

Additional Implications

Our findings also have treatment, assessment, and methodological implications. Researchers have suggested that “…lack of insight is one of the major obstacles standing in the way of successful treatment of the narcissistic personality disorder” (Emmons, 1984, p. 299). Yet, performance-based feedback does not improve narcissists’ self-knowledge because they find ways to undermine the feedback or interpret relatively objective feedback in positive ways (Horton & Sedikides, 2009; Robins & John, 1997; Smalley & Stake, 1996). Our findings suggest that feedback will not improve narcissists’ self-knowledge for a different reason: narcissists already realize that they are narcissistic and have a narcissistic reputation. Perhaps a better intervention strategy will be to emphasize the interpersonal and intrapsychic costs of being seen as narcissistic by others (e.g., Anderson et al., 2006). For example, having a narcissistic reputation might actually result in losing respect and status.

Our multiple-perspectives approach also has implications for personality assessment. Several other studies suggest that others’ perceptions are good indicators of narcissism (e.g., Back et al., 2010; Oltmanns et al., 2004). However, our findings imply that self-perceptions and meta-perceptions are also good indicators of narcissism. Previous work has shown that other-, self-, and meta-perceptions each provide unique information about personality (Oltmanns et al., 2005; Vazire & Carlson, 2010; Vazire & Mehl, 2008). Thus, all three perspectives, other-, self-, and meta-perceptions, might also provide unique information about narcissism. Future research should aim to disentangle when each type of perception is more or less valid and in which contexts.