Abstract

Objectives

The study objective was to examine the relationship between number of emergency departments (EDs) per capita in California counties and measures of socioeconomic status, to determine whether individuals living in areas with lower socioeconomic levels have decreased access to emergency care.

Methods

The authors linked 2005 data from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey of Hospitals with the Area Resource Files from the United States Department of Health and Human Services and performed Poisson regression analyses of the association between EDs per capita in individual California counties using the Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) county codes and three measures of socioeconomic status: median household income, percentage uninsured, and years of education for individuals over 25 years of age. Multivariate analyses using Poisson regression were also performed to determine if any of these measures of socioeconomic status were independently associated with access to EDs.

Results

Median household income is inversely related to the number of EDs per capita (rate ratio = 0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.71 to 0.96). Controlling for income in the multivariate analysis demonstrates that there are more EDs per 100,000 population in FIPS codes with more insured residents when compared with areas having less insured residents with the same levels of household income. Similarly, FIPS codes whose residents have more education have more EDs per 100,000 compared with areas with the same income level whose residents have less education.

Conclusions

Counties whose residents are poorer have more EDs per 100,000 residents than those with higher median household incomes. However, for the same income level, counties with more insured and more highly educated residents have a greater number of EDs per capita than those with less insured and less educated residents. These findings warrant in-depth studies on disparities in access to care as they relate to socioeconomic status.

Keywords: health policy, access to care, access to emergency services, emergency departments per capita

A critical issue nationally in emergency medicine and health policy is the population’s access to emergency services. Factors that affect access across all national markets, including urban, suburban, and rural markets, are the rising demand for emergency services, shortages of hospital nurses and on-call specialists, availability of functioning emergency departments (EDs), number of beds, overcrowding, reduced inpatient capacity, and ambulance diversion.1,2 From 1990 to 1999, the number of EDs in California decreased 12%, whereas the number of total ED visits increased, from approximately 9.0 million to 10.0 million. During the same time period, visits per 100 population increased from 30.0 to 35.0.3,4 Nationally, from 1995 to 2005, the annual number of ED visits increased by 20%, from 96.5 million to 115.3 million. During that same time period, the number of EDs decreased from 4,176 to 3,795. Both nationally and in California, the landscape of emergency services is changing toward fewer EDs per capita despite an increase in visits per capita. The annual number of ED visits in the United States rose by 18% between 1994 and 2004, whereas the number of hospitals operating 24-hour EDs decreased by 12% during the same time frame. Fewer EDs with increasing overall volume led to average increases in the number of cases among operating EDs, up by 78% between 1995 and 2003.5 It is known that ED crowding is most severe in areas with lower household income.6

One basic component of access to emergency services is the presence of an ED in a particular region, as geographic proximity has been shown to play a significant role in patients’ ED use.7 Previous studies have shown that geographical distance not only affects ED utilization, but also reduces utilization in disadvantaged block group areas.8 To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has attempted to characterize the availability of EDs according to a region’s socioeconomic level. This study characterizes one dimension of the availability of emergency services by comparing the number of available EDs per capita across California according to several markers of low socioeconomic status: income, lack of insurance, and fewer years of education.

METHODS

Study Design

This study was a retrospective analysis using cross-sectional data. This project received approval from the institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco.

Study Setting and Population

The data were procured from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey of Hospitals, the AHA System, and Network Profile reports from 2005. We linked these data with the 2005 Area Resource Files from the United States Department of Health and Human Services by Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) county codes. FIPS county codes uniquely identify counties and county equivalents in the United States. We used FIPS county codes to delineate socioeconomic areas within the state of California.

Study Protocol

The AHA survey collects more than 700 fields of information on over 6,300 hospitals. Hospitals report data for a complete fiscal year, and the average response rate is 85%. Data are estimated for nonreporting hospitals, and incomplete responses were filled based on their most recent information, computed from statistical models, or derived from data supplied by similar hospitals. This particular study uses the data from hospitals in California only. There were 58 FIPS county codes in 2005 and 211 EDs in our data set.

Measurements

The outcome variable was the number of EDs per 100,000 for FIPS county codes in California. We measured three independent variables of socioeconomic status: median household income, percentage uninsured, and percentage of people of age ≥25 years with less than 9 years of education. Median household income per FIPS code was the primary predictor used to measure the relationship of socioeconomic status to number of EDs per capita.

Data Analysis

The first analysis focused on the univariate relationship between number of EDs per FIPS county code and each location-specific summary of socioeconomic data. Preliminary assessments of this relationship were based on separate Poisson regression models for the dependence of the number of EDs on income, education, and lack of insurance. The association of each of these variables and number of EDs is summarized by the results of a likelihood ratio test.

The second analysis used Poisson regression models to evaluate the multivariate relationship between number of EDs and income, education, and lack of insurance. All models adjusted for FIPS code-specific population sizes via inclusion of an offset term, allowing results to be expressed in terms of number of EDs per 100,000 individuals in the population. Models used categorical versions of median household income, percentage uninsured, and percentage of people age ≥25 years with less than 9 years of education. Median household income was divided into categories based on intervals increasing by $10,000. Categories for percentage uninsured and percent of people age ≥25 years with less than 9 years of education were constructed using tertiles of the respective distributions. The first, second, and third tertiles of percentage uninsured represent better insured, moderately insured, and poorly insured populations, respectively. The first, second, and third tertiles of percentage of people age ≥25 years with less than 9 years of education represent better educated, moderately educated, and poorly educated populations, respectively. To allow for the possibility that the effects of these socioeconomic indicators were inter-related, initial models included two-way interactions between income and education as well as income and lack of insurance. The two-way interaction terms between income and education, as well as income and percentage uninsured, were not found to be significant and, therefore, were not included in the final model. All analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Graphical display of results was based on additional regression models including income as a continuous variable. These models allowed for a nonlinear (quadratic) relationship between income level and number of EDs and had comparable fits to those including income as a categorical factor.

RESULTS

We analyzed all 58 FIPS county codes in California (Table 1). The median population is 175,352, with a range from 1,190 to 9,937,739 persons. The median number of EDs per capita (100,000) is 0.7, with a range from 0 to 11. The median household income is $40,521, with a range from $28,072 to $70,854. The median percentage without health insurance is 17.6%, with a range from 9.8% to 32.1%. The median percentage with poor education is 10.1%, with a range from 1.8% to 23.8%.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Population in FIPS code (n = 58), median (range) | 175,353 (1,190–9,937,739) |

| EDs per 100,000 population, median (range) | 0.73 (0–11) |

| Median household income in FIPS code, n (%) | |

| $20,001–$30,000 | 4 (6.9) |

| $30,001–$40,000 | 25 (43.1) |

| $40,001–$50,000 | 14 (24.14) |

| $50,001–$60,000 | 10 (17.24) |

| $60,001–$70,000 | 3 (5.17) |

| $70,001–$80,000 | 2 (3.45) |

| Percentage of population in FIPS code without health insurance, median (range) | |

| Low, <16.3% | 20 (9.8–16.3) |

| Medium, 16.3%–19.3% | 19 (16.5–19.3) |

| High, >19.3% | 19 (19.8–32.1) |

| Percentage of adults in FIPS code >25 years with less than 9 years of education, median (range) | |

| Low, <5.2% | 20 (1.8–5.2) |

| Medium, 5.2%–10.5% | 20 (5.9–10.5) |

| High, >10.5% | 18 (10.6–23.8) |

Low = lower one-third of sample; middle = middle one-third of sample; high = upper one-third of sample.

FIPS = Federal Information Processing Standard.

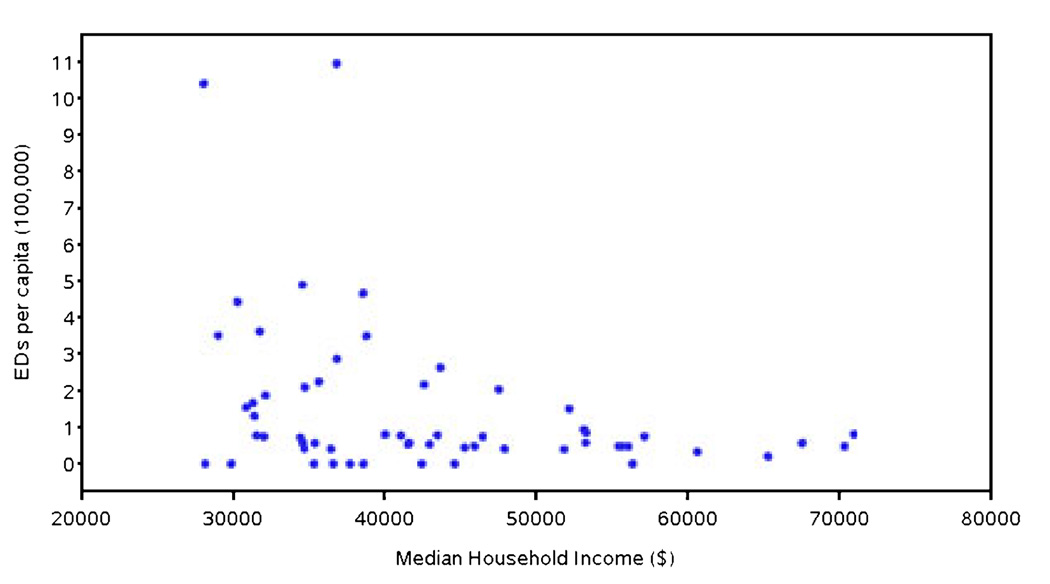

The number of EDs per capita in California was inversely related to the primary predictor of median household income (Figure 1). The estimated relative decrease in the number of EDs associated with each unit increase in income was 0.83 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.71 to 0.96). The likelihood ratio test from the corresponding Poisson regression model was significant for income modeled either as a continuous or as a categorical factor (p = 0.01). No significant association was found between the number of EDs and either percentage of uninsured (p = 0.97) or percentage of individuals with less than 9 years of education (p = 0.33; Table 2).

Figure 1.

Relationship between income and EDs per 100,000 population.

Table 2.

Poisson Regression Model Relating Number of EDs per 100,000 Population With Income, Percentage With Poor Education, and With No Insurance

| Variable | Value | Relative Rate (95% CI) | p-value for trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Income | $20,001–$30,000 | 1.00 | 0.003 |

| Income | $30,001–$40,000 | 0.60 (0.14–2.50) | |

| Income | $40,001–$50,000 | 0.33 (0.08–1.38) | |

| Income | $50,001–$60,000 | 0.33 (0.08–1.39) | |

| Income | $60,001–$70,000 | 0.13 (0.02–0.65) | |

| Income | $70,001–$80,000 | 0.24 (0.05–1.18) | |

| No insurance | T1: [0–16.3%] | 1.00 | 0.63 |

| No insurance | T2: [16.3%–19.3%] | 0.81 (0.52–1.25) | |

| No insurance | T3: >19.3 | 0.83 (0.46–1.52) | |

| Education < 9 yr | T1: [0–5.2%] | 1.00 | 0.23 |

| Education < 9 yr | T2: [5.2%–10.5%] | 0.63 (0.36–1.09) | |

| Education < 9 yr | T3: >10.5% | 0.58 (0.30–1.13) |

T = tertile.

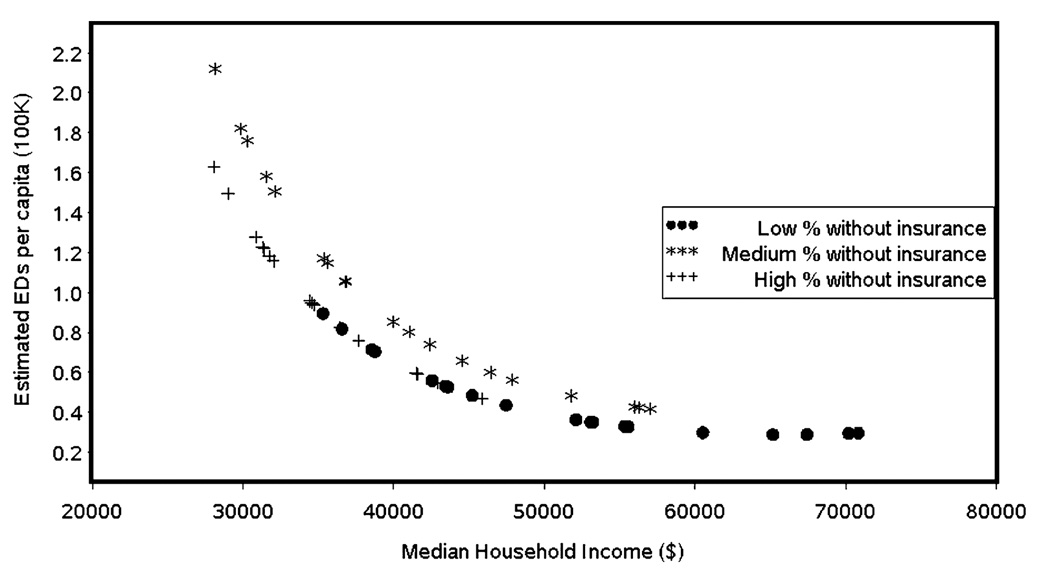

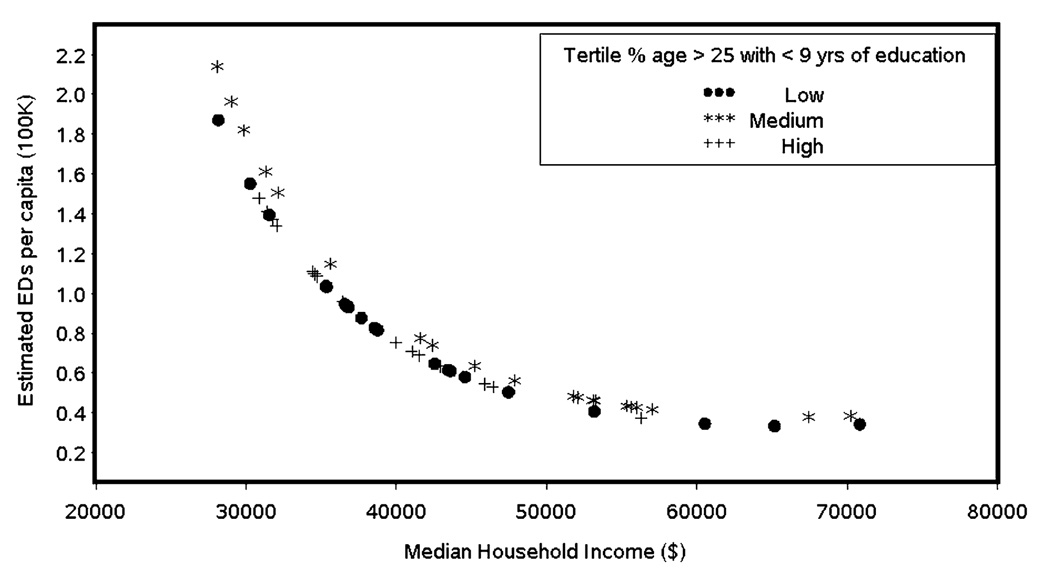

We further examined the relationship of income and percentage uninsured to the number of EDs using a multivariate Poisson regression model, adjusting for median household income and education level. Results indicate that better insured FIPS areas have 1.93 times as many EDs as FIPS areas with a greater number of uninsured (95% CI = 1.34 to 3.01). This relationship of areas with more insured residents having a greater number of EDs is constant across tertiles; when adjusted for median household income, moderately insured FIPS areas (i.e., in the middle tertile of the uninsured), for example, have 1.41 times as many EDs as poorly insured FIPS areas (95% CI = 0.99 to 2.00). When controlling for insurance, areas with higher income have fewer EDs. For each $10,000 increase in median household income, the rate of EDs decreases by 33% (95% CI = 18% to 45%; p = 0.0001; Table 3 and Figure 2). For the same income level, FIPS areas whose residents are better educated have about twice as many EDs as FIPS areas with a high percentage of less educated people, with a rate ratio of 1.99 (95% CI = 1.22 to 3.25; Table 4 and Figure 3).

Table 3.

Number of EDs per 100,000 Population (95% CI) by Income According to Percentage With No Insurance in FIPS Code

| Median Household Income, US$ |

Low Percentage With No Insurance (≤16.3%) |

Medium Percentage With No Insurance (16.3%–19.3%) |

High Percentage With No Insurance (>19.3%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| $20,001–$30,000 | 2.60 (0.61–11.03) | 2.06 (0.51–8.41) | 2.28 (0.52–10.06) |

| $30,001–$40,000 | 1.72 (0.99–3.00) | 1.37 (0.82–2.30) | 1.52 (0.75–3.05) |

| $40,001–$50,000 | 0.91 (0.56–1.48) | 0.72 (0.45–1.16) | 0.80 (0.41–1.55) |

| $50,001–$60,000 | 0.84 (0.53–1.33) | 0.67 (0.40–1.13) | 0.74 (0.34–1.64) |

| $60,001–$70,000 | 0.38 (0.18–0.79) | 0.30 (0.12–0.71) | 0.33 (0.12–0.88) |

| $70,001–$80,000 | 0.64 (0.32–1.26) | 0.51 (0.22–1.17) | 0.56 (0.21–1.53) |

FIPS = Federal Information Processing Standard.

Figure 2.

EDs per 100,000 population by income according to percentage with no insurance in FIPS code. FIPS = Federal Information Processing Standard.

Table 4.

Number of EDs per 100,000 Population (95% CI) by Income According to Percentage With Poor Education in FIPS Code

| Median Household Income, US$ |

Low Percentage With Poor Education (0%–5.2%) |

Medium Percentage With Poor Education (5.2%–10.5%) |

High Percentage With Poor Education (>10.5%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| $20,001–$30,000 | 2.54 (0.59–10.95) | 1.59 (0.39–6.45) | 1.47 (0.33–6.60) |

| $30,001–$40,000 | 1.52 (0.88–2.62) | 0.95 (0.60–1.50) | 0.88 (0.53–1.47) |

| $40,001–$50,000 | 0.85 (0.48–1.49) | 0.53 (0.37–0.76) | 0.49 (0.30–0.81) |

| $50,001–$60,000 | 0.83 (0.42–1.65) | 0.52 (0.36–0.76) | 0.48 (0.27–0.86) |

| $60,001–$70,000 | 0.32 (0.13–0.78) | 0.20 (0.08–0.50) | 0.19 (0.07–0.50) |

| $70,001–$80,000 | 0.62 (0.25–1.56) | 0.39 (0.18–0.82) | 0.36 (0.15–0.84) |

“Poor education” refers to percentage of people age 25 or older with less than 9 years of education.

FIPS = Federal Information Processing Standard.

Figure 3.

EDs per 100,000 population by income according to percentage with poor education in FIPS code. FIPS = Federal Information Processing Standard.

DISCUSSION

We find, contrary to our original hypothesis, that the number of EDs per capita in California is inversely associated with median household income. A closer look beyond these averages in our multivariate analyses, however, shows that across areas with varying insurance and education, there are clear disparities in availability of EDs. When median household income is held constant, areas with more insured residents have more EDs than those with more uninsured residents, and areas with better-educated residents have more EDs than areas whose residents are less educated.

These results suggest that, at least in California, low income is not necessarily associated with decreased availability of emergency care as measured by number of EDs in a FIPS county code region, but that there are relationships between availability of EDs and a combination of the socioeconomic factors of insurance and education. It is possible that, when controlling for income, areas with better educated and more insured populations have more working-class people and have more EDs per capita because their population’s ED visits are compensated by insurance. Conversely, it is possible that, when controlling for income, areas with less educated and more uninsured populations have fewer EDs per capita because the EDs in those areas have more financial difficulty remaining open or opening in the first place.

Characterizing the availability of EDs as they relate to socioeconomic status is also important in informing the current debate about regionalization of ED services. Studies show that directing patients to facilities with optimal capabilities for any given type of illness or injury can improve outcomes and reduce costs. By assessing the availability of emergency services and the capabilities of these services, services can be better organized to provide optimal care based on the patient’s location and condition.9

Our findings substantiate concerns of some practitioners and policy-makers, that emergency services may not be as accessible to populations with lower insurance and education levels, which may relate to varying demand for emergency services based on certain population characteristics. For example, EDs classified as having a high safety-net burden, in terms of serving vulnerable populations, are also shown to have a higher percentage of patients who leave without being seen by a physician.10

An example of some concerns regarding usage of emergency services by vulnerable populations is demonstrated in the literature. Previous studies have shown that two factors associated with low socioeconomic status, a lack of health insurance coverage and a lack of a regular source of care, were positively associated with two or more ED visits over the course of 3 months.11 Other data show that Medicaid patients account for the largest percentage of ED visits when compared with uninsured or privately insured patients. Medicaid patients also make up the largest proportion of patients seeking nonemergent care in EDs.2 Little or no education, another variable associated with low socioeconomic status, has also been associated with routine ED use.12 These concerns, along with the findings of our study, illustrate the problems that factor into taking socioeconomic status into account when making emergency services available to diverse populations.

Despite the evidence that vulnerable populations utilize emergency services more frequently, hospitals are mainly adding capacity in suburban markets with higher household income.6 While previous studies show that overall ED bed capacity per capita may be increasing,4 there have been no studies that look at the distribution of this increased bed capacity. We show that the number of EDs in FIPS codes varies by insurance coverage and education across income levels in predictable ways, so that areas whose residents are insured and who are better educated are consistently associated with a greater number of available EDs. Viewed in the context of existing literature, our results suggest that despite an increased number of EDs in low-income areas, a more useful method to determine the need for future emergency services may be according to the percentage of uninsured and less educated residents in a given region, as these factors may influence need more accurately. Uninsured and less educated residents may require increased utilization of emergency services due to factors that cannot be explained by income alone.

While we find a significant negative relationship between number of EDs per capita and income, our results show that when insurance and education are considered, there are clear disparities in communities that have more: those with “more” insurance and “more” education also have “more” availability to EDs (as defined in our study by number of EDs per capita).

LIMITATIONS

This study was based on cross-sectional data for the year 2005 and therefore is not able to capture recent changes in the dynamic market of health services. It is indeed possible that since 2005, the number of EDs in both low- and high-income FIPS counties has changed, altering our results. Our hypothesis, based on historical data regarding the more market-driven influences of hospital and ED openings and closures, would suggest that the univariate inverse relationship between EDs and income might, at this point in time, be weaker, which would make our findings conservative.

Second, the results could be skewed due to a wide range of population in FIPS county codes in California. Counties with large populations have a wide range of socioeconomic levels, and using the median household income may not be an accurate representation of socioeconomic status. Even though we controlled for population by looking at EDs per capita (or 100,000 population), outliers with very small and very large populations could skew the correlation results for EDs per capita versus income.

Third, while our focus is on the availability of emergency services that can provide a broad range of services, our study does not take into account the presence of minute clinics or urgent care clinics as a potential alternative source of providing care for certain conditions. These facilities could potentially be related to access issues, but we would believe them to be more prevalent in higher income areas, thus making our estimates conservative.

Finally, our study does not account for geographical considerations such as proximity to an ED outside of the county. Specifically, people may not necessarily seek emergency care at an ED within their FIPS county code, particularly if an ED outside of their FIPS code is closer or more accessible (which could be defined not simply by proximity, but by insurance networks, language, or culture). The presence of an ED may not be an exact indicator of access.

We chose not to look at the number of ED beds, as our intent was to identify availability of EDs (as a hospital service line), because ED bed density is a limited dimension of access and cannot apply to those living in areas where an actual ED does not exist. However, size of an ED in terms of bed capacity does factor into access; it may be helpful to perform this type of analysis in the future. It may also be helpful to analyze the relationship between outcomes and proximity to an ED.

CONCLUSIONS

California counties whose residents are poorer have more EDs per 100,000 residents than those with higher median household incomes. However, for the same income level, counties with more insured and more highly educated residents have a greater number of EDs per capita than those with less insured and less educated residents. This study has important policy implications for ED patients as well as the delivery of emergency services in California. These findings shed some light on the phenomenon of overcrowding in low socioeconomic areas—despite a greater number of EDs in poorer areas, other factors may determine availability of services. Even though our chosen measure of number of EDs per population may not be an exact indicator of access and capacity, the combination of such measures can provide additional data to policy-makers. These data suggest that reexamining and possibly reshaping current policy to address the distinctive need for emergency services in areas whose residents are at a low socioeconomic level may be warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yu-Chu Shen, PhD, for providing hospital data, and Barbara Grimes, PhD, and Stephen Shibowski, PhD, for statistical oversight of this project. We are extremely grateful to Ellen Weber, MD, for helpful comments in the revision of this draft, as well as Amy Markowitz, JD, for editorial assistance.

This publication was supported by a grant under The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Physician Faculty Scholars Program and NIH/NCRR/OD UCSF-CTSI Grant KL2 RR024130. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Presented at the American College of Emergency Physicians Scientific Assembly, October 2009, Boston, MA.

References

- 1.Siegel B. Health tracking from the field: the emergency department: rethinking the safety net for the safety net. Health Affairs. 2004 March 24;W4:146–148. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.146. Web Exclusive http://content.healthaffairs.org/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.O’Shea JS. The Crisis in America’s Emergency Rooms and What Can Be Done. The Heritage Foundation. Executive Summary Backgrounder #2092. [Accessed Feb 20, 2010];2007 December 28; Available at: http://www.heritage.org/Research/Healthcare/bg2092.cfm.

- 3.Lambe S, Washington DL, Fink A, et al. Trends in the use and capacity of California’s emergency departments, 1990–1999. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:389–396. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.122433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melnick GA, Nawathe AC, Bamezai A, Green L. Emergency department capacity and access in California, 1990–2001: an economic analysis. Health Affairs. [Accessed Feb 20, 2010]; doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.136. Web Exclusive Available at: http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/abstract/hlthaff.w4.136. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Burt CW, McCaig LF. Staffing, capacity, and ambulance diversion in emergency departments: United States, 2003–04. Adv Data. 2006;376:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fields WW. From the field: emergency care in California: robust capacity or busted access? Health Aff. [Accessed Feb 20, 2010]; doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.143. Web Exclusive. Available at: http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/abstract/hlthaff.w4.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ludwick A, Fu R, Warden C. Distances to emergency department and to primary care provider’s office affect emergency department use in children. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:411–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JE, Sung JH, Ward WB, Fos PJ, Lee WJ, Kim JC. Utilization of the emergency room: impact of geographic distance. Geospat Health. 2007;1:243–253. doi: 10.4081/gh.2007.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine. At the Breaking Point. The Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Characteristics of emergency departments serving high volumes of safety-net patients: United States, 2000. Vital Health Stat. 2004;13:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker D, Stevens C, Brook R. Determinants of emergency department use: are race and ethnicity important? Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:677–682. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong R, Baumann BM, Boudreaux ED. The emergency department for routine healthcare: race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and perceptual factors. J Emerg Med. 2007;32:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2006.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]