Abstract

The bacterial envelope plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of infectious diseases. In this review, we summarize the current knowledge of the structure and molecular composition of the Legionella pneumophila cell envelope. We describe lipopolysaccharides biosynthesis and the biological activities of membrane and periplasmic proteins and discuss their decisive functions during the pathogen–host interaction. In addition to adherence, invasion, and intracellular survival of L. pneumophila, special emphasis is laid on iron acquisition, detoxification, key elicitors of the immune response and the diverse functions of outer membrane vesicles. The critical analysis of the literature reveals that the dynamics and phenotypic plasticity of the Legionella cell surface during the different metabolic stages require more attention in the future.

Keywords: Legionella pneumophila, bacterial envelope, phospholipids, membrane proteins, LPS, outer membrane vesicles

Bacterial cell envelopes fulfill several basic functions: They protect the bacterium from environmental hazards, they allow a selective passage of nutrients into and a specific export of waste products and secretion system substrates out of the cell. Additionally, they mediate the direct contact with other organisms. This holds particularly true for pathogenic bacteria, whose often highly specific interactions with host organisms depend largely on their surface structures. Accordingly, the ability of the Gram-negative facultative intracellular bacterium Legionella pneumophila to cause Legionnaires’ disease hinges predominantly on the components and characteristics of its cell envelope.

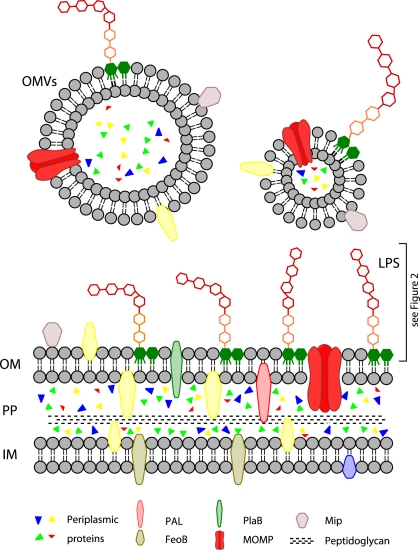

The cytoplasm of Gram-negative bacteria is bordered by the inner membrane. It consists of a bilayer of two phospholipid leaflets with integral and peripheral proteins and lipoproteins. It harbors metabolic enzymes, components of the respiratory chain and parts of the iron acquisition machinery (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of the L. pneumophila cell envelope. CP, cytoplasm; IM, inner membrane; PP, periplasm; OM, outer membrane; OMVs, outer membrane vesicles; LPS, lipopolysaccharides; PAL, peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein; FeoB, iron transporter; PlaB, phospholipase A/lysophospholipase A; MOMP, major outer membrane protein; Mip, macrophage infectivity potentiator.

The periplasm contains a relatively thin layer of peptidoglycan and different proteins. Legionella peptidoglycan is strongly crosslinked (Amano and Williams, 1983). The periplasm is the location of many detoxifying enzymes which degrade harmful substances from the environment. Secretion machineries which cross two membranes also go through the periplasmic space.

The outer membrane is asymmetric with an inner leaflet of mostly phospholipids and an outer leaflet of mostly lipopolysaccharides (LPS). It harbors proteins with diverse functions in virulence such as adhesion and uptake into host cells. Legionella LPS has a unique architecture, particularly concerning the hydrophobic O-antigen.

Certain types of surface appendages such as pili and flagella, which are required for bacterial motility and pathogenicity, are anchored in the inner membrane and protrude into the extracellular space (Liles et al., 1998; Stone and Abu Kwaik, 1998; Heuner and Steinert, 2003).

Virulence properties of outer membrane components are particularly important in regard to outer membrane vesicles (OMVs). Like most bacteria, L. pneumophila sheds these vesicles from its outer membrane. OMVs are spherical lipid bilayers and contain outer membrane components and periplasmic proteins.

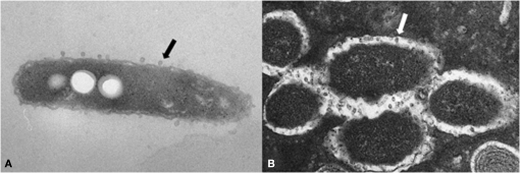

The actual structure of the L. pneumophila cell envelope was assessed in detail by electron microscopy shortly after the discovery of the bacterium (Rodgers and Davey, 1982). Both membranes and the peptidoglycan layer were visualized by different methods, resulting in vivid images of the components that are, nowadays, analyzed mostly biochemically. The authors are also the first to show the existence of OMVs of L. pneumophila, even though they are termed “blebs” and explained as “condensed pili-related proteins or random structural proteins of the outer membranes.” An extensive study of L. pneumophila morphology including envelope architecture was performed by Faulkner and Garduño (2002). They hypothesize the existence of several morphological variants, each corresponding to a certain growth phase or stage of the infection cycle. Interestingly, five different envelope structures are presented which vary in thickness, number of membrane layers, and electron density of individual components. As some of the morphological variants only occurred during intracellular growth, the authors propose that the development of these variants depends on host metabolites. This notion can explain the absence of these forms during extracellular growth in liquid media. The impact of processing artifacts arising during the preparation of the samples, however, remains to be clarified.

Many secretion systems and outer membrane proteins with roles in virulence have been excellently reviewed elsewhere and are not within the focus of this work. This includes T1SS and twin-arginine translocation (Tat) secretion (Lammertyn and Anne, 2004), T2SS (Cianciotto, 2009), T4SS as well as their respective translocated effectors (Ninio and Roy, 2007). Finally, secreted phospholipases connect Legionella virulence to host lipids (Banerji et al., 2008). Less attention was paid to other components of the Legionella cell envelope which are not part of the aforementioned complexes. This review concentrates on these envelope components and how they mediate Legionella virulence properties.

The Inner Membrane of L. Pneumophila

Starting from the inside and proceeding outward, the first layer is the inner membrane, also termed cytoplasmic or plasma membrane. It is a lipid bilayer with integrated components of various systems, including the iron uptake machinery, the respiratory chain, and the detoxification system (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inner membrane proteins of L. pneumophila associated with virulence and survival.

| Protein | Molecular function | Role in infection/required for | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| FeoB | GTP-dependent Fe(II) transporter | Macrophage killing, full virulence in mouse | Petermann et al. (2010), Robey and Cianciotto (2002) |

| IraA/IraB | Small-molecule methyl transferase/ peptide transporter | Iron uptake, infection of human macrophages, and guinea pigs | Viswanathan et al. (2000) |

| Multi-copper oxidase | Potential oxidation of ferrous iron | Extracellular replication | Huston et al. (2008) |

| LadC | Putative adenylate cyclase | Adhesion to macrophages, intracellular replication, putative modification of protein functions via cAMP | Newton et al. (2008) |

| TatB | T2S, additional function(s) | Intracellular replication in human macrophages, growth under iron-limiting conditions, cytochrome c-dependent respiration, export of PLC activity to supernatant | Rossier and Cianciotto (2005) |

The lipid composition of a crude inner membrane preparation of L. pneumophila was analyzed shortly after the discovery of the bacteria (Hindahl and Iglewski, 1984). They described it to contain mainly phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine with smaller amounts of cardiolipin and phosphatidylglycerol. Contamination with outer membrane components cannot be excluded due to methodical reasons. Thus, these data should be interpreted carefully.

An important function of the inner membrane of L. pneumophila is the regulation of iron acquisition, summarized elsewhere (Cianciotto, 2007). Iron uptake is a crucial process during all phases of L. pneumophila growth. It is mainly carried out by the GTP-dependent iron transporter FeoB, which mediates the uptake of Fe(II) (Robey and Cianciotto, 2002; Petermann et al., 2010). The protein is required for optimal growth under iron-limiting conditions in liquid media as well as in iron-restricted amoeba and macrophages. FeoB is required for efficient killing of macrophages and full virulence in a mouse model of Legionnaires’ disease.

Another iron acquisition mechanism involves the proteins IraA and IraB. IraA is described as a small-molecule methyltransferase. It mediates iron uptake and is required for the infection of human macrophages and guinea pigs. IraB is an integral protein of the inner membrane with homology to bacterial peptide transporters. It is suggested to mediate the uptake of iron ions into the cell, possibly chelated by small peptides. The potential significance of the iraAB locus for virulence is underlined by the fact that it is found almost exclusively in pathogenic Legionella, but not in avirulent species (Viswanathan et al., 2000).

The multi-copper oxidase MCO is tethered to the cytoplasmic membrane of L. pneumophila. Recently, this enzyme was suggested to oxidize ferrous iron, which could otherwise lead to the formation of hydroxyl radicals under aerobic conditions (Huston et al., 2008). An MCO-negative mutant displays normal intracellular replication within macrophages. Therefore the function of MCO seems to be limited to extracellular growth, during which the authors hypothesize it to be involved in the protection against iron-related oxidative stress.

Inner membrane proteins often regulate cytoplasmic processes such as gene expression and the synthesis of signal transduction molecules. One example of this is LadC, a putative adenylate cyclase. L. pneumophila expresses the corresponding gene exclusively during intracellular infection. Its importance for virulence is underlined by the finding that a LadC-negative mutant adheres to macrophages less effectively and replicates less within mammalian cells and amoeba. In contrast to most other bacterial adenylate cyclases, LadC does not alter transcriptional profiles, so it is assumed that LadC produces cAMP which, in turn, modifies protein–protein interactions or regulates protein activities (Newton et al., 2008).

The inner membrane is crossed by the Tat complex which can be involved in type II secretion. One of the Tat components, TatB, was found to have additional, unexpected functions (Rossier and Cianciotto, 2005). Firstly, intracellular replication in human macrophages is impaired in the absence of TatB independently of type II secretion. Secondly, TatB-negative mutants are defective in growth under iron-limiting conditions, both extracellularly and within amoeba. Moreover, TatB of L. pneumophila is also required for cytochrome c-dependent respiration and finally for the export of a specific phospholipase C activity to the culture supernatant – possibly executed by PlcA.

The inner membrane is also the starting point of several secretion systems. The unique Dot/Icm system of Legionella has been reviewed very well elsewhere as has the type II secretion system (Cianciotto, 2009; Hubber and Roy, 2010).

In summary, the inner membrane of L. pneumophila influences virulence functions rather indirectly via the mediation of iron acquisition and other cellular processes such as protein secretion. The contribution of inner membrane components to virulence may emerge from enhanced survival under hostile conditions – and infection processes may just be an example for this. From this perspective, findings which relate survival factors to virulence may simply be due to the fact that host cells and tissues are examples of hostile environments to most bacteria.

Periplasm

The periplasmic space is a gel-like layer composed of soluble proteins and strongly crosslinked peptidoglycan located between the outer and inner membranes. It is enriched in proteases and nucleases and other degradative enzymes. Thus, the periplasm has been called an “evolutionary precursor of the lysosomes of eukaryotic cells” (Silhavy et al., 2010).

The presence of digestive enzymes was confirmed by recent L. pneumophila membrane proteome data. It has been shown that mainly enzymes were found in the periplasm, such as metalloproteases, phosphatases, isomerases, the periplasmic components of the Dot/Icm machinery and other proteins involved in L. pneumophila virulence that promote penetration of host cells (Cirillo et al., 2000; Khemiri et al., 2008).

Legionella pneumophila peptidoglycan was shown to contain muramic acid, glucosamine, glutamic acid, alanine, and meso-diaminopimelic acid (meso-DAP). Interestingly, extremely strong crosslinking was observed, with approximately 85% of meso-DAP and 90% of alanine residues contributing to these crosslinks. Peptidoglycan was found to be partially resistant to lysozyme treatment. The stable peptidoglycan layer is likely to promote survival in hostile environments (Amano and Williams, 1983). The important role of peptidoglycan in virulence is underlined by the finding that DAP-auxotroph L. pneumophila mutants display impaired survival within macrophages and amoeba (Amano and Williams, 1983).

Peptidoglycan fragments of many bacteria are recognized by members the NLR family of receptors (Nucleotide-binding domain, Leucine-Rich repeat-containing proteins) in the host cytosol. Their activation leads to inflammatory responses. Interestingly, L. pneumophila cell extracts and culture supernatants activate two members of this family, NOD1 and NOD2 (Nucleotide-binding, Oligomerization Domain-containing proteins 1 and 2), only to a very small extent (Hasegawa et al., 2006). Why L. pneumophila is only weakly detected by NLRs and the details of its recognition by the host has to be the subject of future investigations.

The periplasm harbors many enzymes which degrade harmful substances that enter the bacterial cell. One example is the L. pneumophila copper–zinc–superoxide dismutase (Cu–Zn–SOD). It was shown that this enzyme is essential for survival in the stationary growth phase. As Legionella has to survive for long periods when no host is available, the Cu–Zn–SOD may aid the bacteria to overcome oxidative stress encountered during this period. Interestingly, copper–zinc oxidases occur in many eukaryotes, but only in very few bacteria such as Haemophilus influenzae, Brucella abortus, and Escherichia coli. A general involvement of this enzyme class in microbial virulence is discussed (Schnell and Steinman, 1995; St John and Steinman, 1996).

The hydrogen peroxide which is produced by the Cu–Zn–SOD can be converted to H2O and O2 by the periplasmic katalase KatA. KatA and its cytoplasmic counterpart KatB are both required for optimal infection cycles in primary macrophages and amoeba (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2003). The authors propose a model in which KatA and KatB maintain a low intracellular H2O2 level, which is required for optimal function of the Dot/Icm apparatus and many other processes.

One of the Dot/Icm machinery components, IcmX, was localized to the L. pneumophila periplasm. This protein is required for the establishment of the Legionella-containing vacuole and pore formation in macrophage cell membranes, yet these effects are independent of an intact Dot/Icm apparatus. A truncated form of IcmX is secreted into culture supernatants, but not into the cytoplasm of host cells (Matthews and Roy, 2000). Intriguingly, a sequence near the C terminus of the IcmX gene is annotated to contain a DNA polymerase domain of the POLBc superfamily. If this holds true, the purpose of a periplasmic DNA polymerase remains to be clarified.

Many periplasmic components contribute to L. pneumophila virulence and some may be involved in bacterial protection against immune defense mechanisms (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Periplasmic proteins of L. pneumophila associated with virulence and survival.

| Protein | Molecular function | Role in infection/required for | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper–zinc–superoxide dismutase | Detoxification of superoxide radicals | Stationary growth survival | St John and Steinman (1996) |

| KatA | Degradation of H2O2 | Optimal infection of macrophages and amoeba (optimal function of the Dot/Icm apparatus) | Bandyopadhyay et al. (2003) |

| IcmX | Putative DNA polymerase (POLBc superfamily) | Establishment of the Legionella-containing vacuole, pore formation in macrophage cell membranes | Matthews and Roy (2000) |

The Outer Membrane

The OM is the distinguishing feature of all Gram-negative bacteria. It is a lipid bilayer composed of phospholipids, lipoproteins, LPS, and proteins. Phospholipids are located mainly in the inner leaflet of the outer membrane, as are the lipoproteins that connect the outer membrane to peptidoglycan. The outer membrane is the location of mature LPS molecules and the shedding of OMVs.

The phospholipids of L. pneumophila were analyzed shortly after the discovery of the bacteria (Finnerty et al., 1979). They are, in decreasing order of concentration, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, cardiolipin, monomethylphosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerol, and dimethylphosphatidylethanolamine. It remains unclear whether the lipid composition of the outer membrane differs significantly from that of the inner membrane (Hindahl and Iglewski, 1984; Gabay and Horwitz, 1985).

The discovery of phosphatidylcholine is striking as only about 10% of all known bacteria contain this lipid in their membranes – mostly those bacteria that are closely associated with eukaryotes. Examples include Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, and B. abortus. Nevertheless the exact function of this phospholipid in bacterial cell envelopes remains unknown (Sohlenkamp et al., 2003). Intriguingly, the loss of phosphatidylcholine from the L. pneumophila envelope causes reduced cytotoxicity and lower yields of bacteria within macrophages (Conover et al., 2008). Additionally the strains lacking this lipid bind to macrophages less effectively. Recently it was shown that Legionella bozemanae synthesizes phosphatidylcholine from exogenous choline (Palusinska-Szysz et al., 2011).

In addition to phospholipid species, the fatty acid composition of membranes also influences bacterial properties. In the stationary growth phase of L. pneumophila, the proportion of branched-chain fatty acids rises to over 60% and the average length of fatty acids in phospholipid molecules decreases compared to exponential growth. This change in fatty acid composition leads to an increased tolerance to the antimicrobial peptide warnericin RK (Verdon et al., 2011). The contribution of fatty acids to Legionella infection processes is still unknown. Future studies will shed more light on the influence of lipids on membrane protein structures, localization, and functions. In addition, the existence of distinct lipid domains in L. pneumophila membranes has not been described so far.

A bioinformatic approach proposed around 250 proteins in the L. pneumophila OM, however, most of their functions still need to be elucidated (Khemiri et al., 2008). With few exceptions, the proteins of the OM can be divided into two classes, lipoproteins and β-barrel proteins. Lipoproteins have lipid moieties attached to an amino-terminal cysteine residue (Sankaran and Wu, 1994). β-barrel proteins are nearly all integral membrane proteins of the outer membrane. Most outer membrane proteins are involved in either attachment or invasion of host cells. Both classes of proteins are in direct contact with the environment and host cells. They are therefore preferential targets for vaccine development as well as for diagnosis (Silhavy et al., 2010).

One such example is the 19-kDa peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein (PAL) which is a species-common immunodominant antigen for the diagnosis of Legionnaires’ disease (Kim et al., 2003; Shim et al., 2009). This protein activates murine macrophages via toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and induces the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α (Table 3).

Table 3.

Outer membrane proteins of L. pneumophila associated with virulence and survival.

| Protein | Molecular function | Role in infection/required for | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAL | Activation of murine macrophages via TLR2, induction of the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α | Kim et al. (2003), Shim et al. (2009) | |

| DotD, DotC, IcmN | Intracellular survival | Nakano et al. (2010), Yerushalmi et al. (2005) | |

| PlaB | Phospholipase A/lysophospholipase A | Contact-dependent hemolytic activity and plays an important role in guinea pig infection | Schunder et al. (2010) |

| MOMP | Porin | attachment to host cells | Bellinger-Kawahara and Horwitz (1990), Krinos et al. (1999) |

| Hsp60 | Attachment to and invasion of a HeLa cell | Garduño et al. (1998), Hoffman and Garduño (1999) | |

| Mip | Peptidyl–prolyl cis/trans isomerase | Efficient replication within host cells and transmigration across an in vitro model of the lung epithelial barrier | Wagner et al. (2007), Debroy et al. (2006) |

| Lcl | Collagen-like protein | Adherence to and invasion of host cells | Vandersmissen et al. (2010) |

Three of the T4SS components (DotD, DotC, IcmN) contain a lipobox motif at their N terminus and are predicted to be lipoproteins. DotD and DotC are essential for bacterial intracellular survival (Yerushalmi et al., 2005; Nakano et al., 2010).

For L. pneumophila, several outer membrane proteins are characterized as important virulence factors. An example of an outer membrane-associated and at least partially surface-exposed protein with virulence functions is PlaB (major cell-associated phospholipase A/lysophospholipase A). It displays contact-dependent hemolytic activity and plays an important role in guinea pig infection (Schunder et al., 2010).

The L. pneumophila major outer membrane protein (MOMP) is involved in the attachment to host cells (Gabay et al., 1985; Bellinger-Kawahara and Horwitz, 1990; Mintz et al., 1995; Krinos et al., 1999). The heat shock protein Hsp60 is also important for attachment to and invasion of a HeLa cell model (Garduño et al., 1998; Hoffman and Garduño, 1999).

Mip, the macrophage infectivity potentiator, is a membrane-associated homodimeric protein that is mainly found on the bacterial surface (Riboldi-Tunnicliffe et al., 2001). The C-terminal domain of Mip displays peptidyl–prolyl cis/trans isomerase (PPIase) activity. It is related to the human FK506-binding protein and binds to collagen of types I, II, III, IV, V, and VI. The protein is necessary for efficient replication within host cells. Interestingly, it is also required for the transmigration of L. pneumophila across an in vitro model of the lung epithelial barrier (Wagner et al., 2007).

The substrate of Mip and its exact function in virulence have not been identified yet. A step toward this goal was the finding that Mip is required for the extracellular release of an phospholipase C-like activity. Mip may mediate this by activating the secreted enzyme – and potentially other proteins – directly after secretion of one of the secretion machinery components by its PPIase activity (Debroy et al., 2006).

The Legionella collagen-like protein Lcl contains an outer membrane motif and was shown to contribute to the adherence and invasion of host cells. Interestingly, the number of repeat units present in the lcl gene has an influence on these adhesion characteristics (Vandersmissen et al., 2010).

In summary, the outer membrane is the direct interface between L. pneumophila and its host organisms. Some of its proteinaceous components are directly involved in adhesion and invasion processes (Table 3). The influence of lipid composition on the functions of OM virulence factors remains to be elucidated.

L. pneumophila LPS

Lipopolysaccharides are located in the outer leaflet of the outer membrane and they are a major immunodominant antigen of Legionella. Based on O-antigen architecture, the species L. pneumophila can be divided into at least 15 serogroups (Helbig and Amemura-Maekawa, 2009). Within each serogroup, so-called monoclonal subgroups can be defined. For example, serogroup 1 can be divided into 10 subgroups (Ciesielski et al., 1986). The species L. pneumophila accounts for about 90% of the cases of legionellosis, and about 85% of these are caused by members of serogroup 1 (Helbig et al., 2002; Doleans et al., 2004; Gosselin et al., 2010; Napoli et al., 2010). For this reason, most researchers focus on serogroup 1, and this chapter, too, describes the chemical structure and functions of L. pneumophila serogroup 1 LPS.

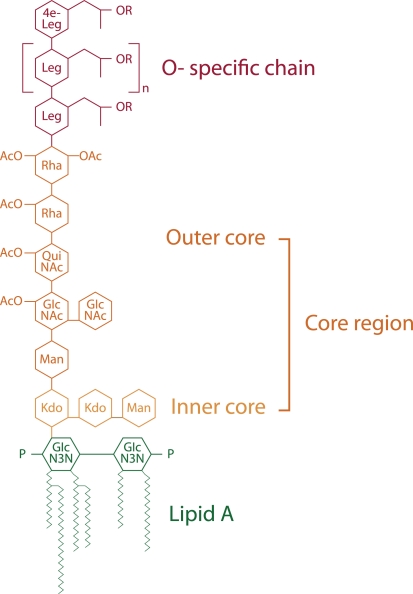

In comparison to the LPS of other Gram-negative bacteria, the L. pneumophila LPS has a unique structure. Due to high levels of long, branched fatty acids, and elevated levels of O- and N-acetyl groups, this LPS is highly hydrophobic (Figure 2). LPS molecules consist of the O-specific chain, the core region, and the lipid A component, which is also called endotoxin. The O-chain and the core constitute the polysaccharide region of the LPS, whereas lipid A represents the part of the molecule which anchors the LPS in the outer membrane.

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of L. pneumophila LPS (modified from Kooistra et al., 2002b). Structure indicates its various regions: O-specific chain, core region consisting of the outer core and inner core and lipid A. Leg, derivatives of legionaminic acid; 4e-Leg, derivatives of 4-epilegionaminic acid; Rha, rhamnose; Man, mannose; QuiNAc, acetylquinovosamine; GlcNAc, acetylglucosamine; Kdo, 3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid; P, phosphate; OAc, O-acetyl.

The O-chain of L. pneumophila LPS is a homopolymer of the unusual sugar 5-acetamidino-7-acetamido-8-O-acetyl-3,5,7,9-tetradeoxy-L-glycero-D-galacto-nonulosonic acid, termed legionaminic acid (Palusinska-Szysz and Russa, 2009). This sugar molecule completely lacks free hydroxyl groups and is therefore very hydrophobic (Knirel et al., 1994; Helbig et al., 1995; Zähringer et al., 1995; Kooistra et al., 2002a). The core region consists of the outer core and the inner core. The outer core of L. pneumophila is a oligosaccharide composed of rhamnose (Rha), mannose (Man), acetylquinovosamine (QuiNAc), and acetylglucosamine GlcNAc (Knirel et al., 1996, 1997). Like the O-chain it also exhibits hydrophobic properties, in contrast to the inner core, which is hydrophilic. The inner core oligosaccharide of L. pneumophila LPS is characterized by a 3-deoxy-D-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid (Kdo) disaccharide [α-Kdo-(2α4)-α-Kdo-(2α6)] linked to lipid A which is conserved within many Gram-negative bacteria and is essential for microbial growth (Moll et al., 1997).

Lipid A of L. pneumophila serogroup 1 contains unusual long-chain and branched fatty acids, which may be responsible for its low endotoxic potential (Moll et al., 1992; Neumeister et al., 1998). The structural function of lipid A is anchoring the LPS in the bacterial membrane. Unlike in other Gram-negative bacteria, L. pneumophila lipid A does not function as a classical endotoxin. It was demonstrated that L. pneumophila LPS is about 1000 times less potent in its ability to induce the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines from human monocytic cells than LPS of members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (Neumeister et al., 1998).

LPS biosynthesis and transport

The biosynthesis of LPS is a complex process involving various steps that occur at the inner membrane, following by assembly in the periplasm and translocation of LPS molecules to the bacterial cell surface.

The genes involved in core oligosaccharide and O-chain biosynthesis are mainly localized on a 30-kb gene locus (Lüneberg et al., 2000). The excision of this region from the chromosome leads to an alteration of the LPS epitope and a loss of virulence (Lüneberg et al., 1998, 2001). The L. pneumophila LPS gene locus includes genes with products which are likely to be involved in LPS core oligosaccharide biosynthesis (rmlA-D, glycosyltransferases, acetyltransferase) as well as O-chain biosynthesis and translocation (mnaA, neuB, neuA, wecA, wzt, wzm). The genes involved in LPS biosynthesis and translocation and its distribution among five sequenced and annotated L. pneumophila genomes are summarized in Table 4. Interestingly, the gene cluster coding for the determinants of serogroup 1 LPS is present in diverse serogroups, suggesting that it is mobile and can be exchanged by horizontal gene transfer (Cazalet et al., 2008). The region encoding proteins involved in LPS biosynthesis can be subdivided in two blocks of 13 and 20 kb. Most of the genes in the 13-kb block are present in all L. pneumophila strains, whereas the majority of genes in the 20-kb block are specific for serogroup 1. Three genes, coding for two O-antigen transporters (wzt and wzm) and one hypothetical protein, might be used as markers for Legionella serogroup 1 (Cazalet et al., 2008; Merault et al., 2010).

Table 4.

Paralogs of LPS biosynthesis and translocation proteins in L. pneumophila strains.

| Enzyme | Molecular function | L. pneumophila strains | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corby | Philadelphia-1 | Lens | Paris | 2300/99 Alcoy | ||

| Lipid a biosynthesis | ||||||

| LpxA | UDP–N-acetylglucosamine acyltransferase | LPC_2835 | Lpg0511 | Lpl0549 | Lpp0573 | Lpa_00769 |

| LPC_3254 | Lpg2943 | Lpl2874 | Lpp3016 | Lpa_04308 | ||

| LpxC | UDP–3-O-[3-hydroxymyristoyl] N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase | LPC_0533 | Lpg2608 | Lpl2531 | Lpp2661 | Lpa_03814 |

| LpxD | UDP–3-O-[3-hydroxymyristoyl] glucosamine N-acyltransferase | LPC_0119 | Lpg0100 | Lpl0100 | Lpp0114 | Lpa_00149 |

| LPC_2837 | Lpg0508 | Lpl0547 | Lpp0571 | Lpa_00766 | ||

| LPC_3255 | Lpg2944 | Lpl2873 | Lpp3015 | Lpa_04309 | ||

| LpxH | UDP–2,3-diacylglucosamine hydrolase | LPC_0973 | Lpg1552 | Lpl1474 | Lpp1509 | Lpa_02254 |

| LpxB | Lipid A disaccharide synthase | LPC_0787 | Lpg1371 | Lpl1322 | Lpp1325 | Lpa_02021 |

| LPC_3256 | Lpg2945 | Lpl2872 | Lpp3014 | Lpa_04311 | ||

| LpxK | Tetraacyldisaccharide 4′-kinase | LPC_1262* | Lpg1818* | Lpl1782* | Lpp1781* | Lpa_02629* |

| Tetraacyldisaccharide-1-P-4′-kinase | LPC_1374 | Lpg1920 | Lpl1884 | Lpp1895 | Lpa_02777 | |

| KdtA (WaaA) | 3-Deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid transferase | LPC_1808 | Lpg2340 | Lpl2261 | Lpp2288 | Lpa_03350 |

| LpxL (WaaM) | Lipid A acyltransferase | LPC_2981 | Lpg0363 | Lpl0404 | Lpp0428 | Lpa_00577 |

| LPC_3251# | Lpg2940# | Lpl2870# | Lpp3012# | Lpa_04304# | ||

| LPC_3252# | Lpg2941# | Lpl2871# | Lpp3013# | Lpa_04305# | ||

| Core region biosynthesis | ||||||

| WaaQ | Heptosyl transferase | LPC_0441 | lpg2695 | Lpl2622 | Lpp2749 | Lpa_03933 |

| RmlA (RfbA) | Glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase | LPC_2532 | Lpg0760 | Lpl0797 | Lpp0826 | Lpa_01168 |

| RmlB (RfbB) | dTDP–glucose 4,6-dehydratase RmlB | LPC_2534 | Lpg0758 | Lpl0795 | Lpp0824 | Lpa_01166 |

| RmlC | dTDP–4-dehydrorhamnose 3,5-epimerase | LPC_2536 | Lpg0756 | Lpl0793 | Lpp0822 | Lpa_01164 |

| RmlD | dTDP–6-deoxy-l-mannose dehydrogenase | LPC_2535 | Lpg0757 | Lpl0793 | Lpp0823 | Lpa_01165 |

| Glycosyltransferase | LPC_2515 | Lpg0779 | Lpl0818 | Lpp0843 | Lpa_01190 | |

| Glycosyltransferase | LPC_2516 | Lpg0778 | Lpl0817 | Lpp0842 | Lpa_01189 | |

| O-Chain biosynthesis | ||||||

| KdsA (NeuB) | 3-Deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid (KDO) 8-phosphate synthase | LPC_0649 | Lpg1182 | Lpl1191 | Lpp1185 | Lpa_01838 |

| HAD superfamily transporter hydrolase | LPC_2456 | Lpg0839 | Lpl0870 | Lpp0901 | Lpa_01272 | |

| KdsB | 3-Deoxy-manno-octulosonate | LPC_1373 | Lpg1919 | Lpl1883 | Lpp1894 | Lpa_02777 |

| GmhA | Phosphoheptose isomerase | LPC_3308 | Lpg2993 | Lpl2921 | Lpp3064 | Lpa_04384 |

| HisB | d,d-heptose 1,7-bisphosphate phosphatase | LPC_1283 | Lpg1838 | Lpl1803 | Lpp1802 | Lpa_02656 |

| WecE | Aminotransferase, predicted pyridoxal phosphate-dependent enzyme | LPC_0840 | Lpg1424 | Lpl1375 | Lpp1379 | Lpa_02088 |

| Lag-1 | O-Acetyltransferase, acetylation of the O-polysaccharide | LPC_2517 | Lpg0777 | Lpl0816 | Lpp0841 | Lpa_01188 |

| NeuC (NnaA) | N-Acylglucosamine 2-epimerase | LPC_2539 | Lpg0753 | Lpl0790 | Lpp0819 | Lpa_01161 |

| NeuB | N-Acetylneuraminic acid synthetase | LPC_2540 | Lpg0752 | Lpl0789 | Lpp0818 | Lpa_01160 |

| LPC_2524 | Lpg0768 | Lpg0809 | Lpp0833 | Lpa_01177 | ||

| NeuA | CMP–N-acetylneuraminic acid synthetase | LPC_2541 | Lpg0751 | Lpl0788 | Lpp0817 | Lpa_01159 |

| WecA | O-Antigen initiating glycosyl transferase | LPC_2530 | Lpg0762 | Lpl0799 | Lpp0828 | Lpa_01171 |

| LPS translocation | ||||||

| MsbA | Lipid A export ATP-binding/permease protein MsbA | LPC_1263* | Lpg1819* | Lpl1783* | Lpp1782* | Lpa_02631* |

| Wzt** | LPS O-antigen ABC transporter Wzt | LPC_2519 | Lpg0773 | Lpl0814 | Lpp0838 | Lpa_01186 |

| Wzm** | LPS O-antigen ABC transporter Wzm | LPC_2520 | Lpg0772 | Lpl0813 | Lpp0837 | Lpa_01184 |

The protein paralogs share a high level of homology. In general they have 96–100% of identity and 97–100% of positivity.

#Indicates the proteins with lower homology (73–90%).

*The lpxK–msbA cluster exists in many Gram-negative bacteria. MsbA is known as a specific transporter, which exports core–lipid A from the cytoplasmic to the periplasmic face of the inner membrane, while LpxK phosphorylates the 4′-position of lipid A.

**The genes wzm and wzt are specific for the Sg1 LPS gene cluster and can be used for rapid detection of L. pneumophila Sg1 in clinical and environmental isolates (Cazalet et al., 2008).

Lipid A can be modified, a process which alters the physical properties of the outer membrane (Albers et al., 2007). Some of these modifications are known to be under the control of the PmrA/PmrB and/or the PhoP/PhoQ two-component systems in other Gram-negative organisms (Miller et al., 1989; Guo et al., 1997, 1998; Gunn et al., 1998). Despite the detailed characterization of the PmrA/PmrB two-component system of L. pneumophila and its influence on gene expression of most of virulence determinants, the role of the this system in lipid A modification in Legionella has not yet been analyzed (Al-Khodor et al., 2009; Hovel-Miner et al., 2009; Rasis and Segal, 2009).

PhoP/PhoQ is a two-component system which regulates a number of lipid A-modifying enzymes in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. It was not detected in genomes of the genus Legionella (Gibbons et al., 2005). Nevertheless, it is conceivable that analogs with low protein homology or other two-component systems regulate lipid A-modifying enzymes. One of the genes which is transcriptionally activated by the PhoP/PhoQ system in Salmonella is pagP (Kawasaki et al., 2004). The inactivation of this gene leads to a decreased resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs). The Legionella homolog of pagP is called resistance to CAMPs (rcp) and functions as a palmitoyl transferase, which transfers palmitate to lipid A molecules. The increased palmitoylation is believed to promote resistance to CAMPs by decreasing membrane fluidity and preventing insertion of the peptides (Guo et al., 1998; Bishop et al., 2000; Robey et al., 2001; Soderberg and Cianciotto, 2010). The structural modification of lipid A might help the bacteria to resist CAMPs released by the host immune system, or to evade recognition by TLR4, the innate immune receptor. L. pneumophila rcp influences virulence and the adaptation to Mg2+-limiting conditions (Wang and Quinn, 2010).

After synthesis on the cytoplasmic face, both core-lipid A and O-antigen need to be transported to the periplasmic face of the inner membrane. Little is known about the mechanisms of LPS polymerization and translocation in Legionella. After attachment of the core, nascent core-lipid A is most probably flipped to the periplasmic face of the inner membrane by the ABC transporter MsbA, where the O-antigen polymer is attached (Doerrler et al., 2004). Transport of the O-antigen may occur through an Wzt/Wzm ABC transporter. In all analyzed L. pneumophila genomes, we have found Wzt and Wzm genes (Table 4). Wzm forms a channel in the inner membrane for the passage of the lipid-linked O-antigen, and Wzt provides energy through its ATPase activity (Lüneberg et al., 2000).

It is not known how Legionella LPS is transported from the periplasm to the outer leaflet of the OM. Recently it was shown that in E. coli the LptD/LptE complex performs this function (Ma et al., 2008). The homolog of LptD/LptE was found in L. pneumophila, therefore it can be speculated that the transport of LPS occurs by a related mechanism.

Functions of the Legionella LPS

Members of the TLR family in cells of the innate immune system recognize specific conserved components of microbes, including LPS. This initiates the cascade of the inflammatory response and activates adaptive immunity through the induction of cytokine production and synthesis of co-stimulatory molecules. LPS can be recognized by TLR4, a receptor found on the surface of different immune cells such as macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells (Mintz et al., 1992; Akira et al., 2001). The correlation between a TLR4 polymorphism and its influence on susceptibility to Legionnaires’ disease was reported (Hawn et al., 2005). It is interesting to note that L. pneumophila requires TLR2 rather than TLR4 to elicit the expression of CD14, which acts as a co-receptor for the detection of bacterial LPS. It is hypothesized that long-chain fatty acids and the high hydrophobicity of L. pneumophila lipid A can abolish the interaction with the soluble LPS receptor CD14 and the ability of LPS molecules to activate bone marrow cells (Neumeister et al., 1998; Girard et al., 2003). Remarkably, L. pneumophila is known to up-regulate both, TLR2 and TLR4, and to activate CD40, CD86, and MHC class I/II molecules on dendritic cells (Rogers et al., 2007).

Recently it was demonstrated that LPS of L. pneumophila shed in liquid culture is able to arrest phagosome maturation in amoeba and human macrophages. In particular, the presence of high-molecular-weight LPS correlates with the inhibition of phagosome–lysosome fusion (Seeger et al., 2010). Another group has shown that L. pneumophila LPS specifically interacts with pulmonary collectins and surfactant proteins A and D, which play important roles in innate immunity in the lung. The authors also propose that this interaction promotes the localization of L. pneumophila to an acidic compartment, i.e., lysosomes, and intracellular growth of the bacteria is subsequently inhibited (Sawada et al., 2010).

Interestingly, the LPS pattern of L. pneumophila grown in broth has been found to be different from the pattern of bacteria grown intracellulary in Acanthamoeba polyphaga (Barker et al., 1993). Moreover, during exponential growth, L. pneumophila LPS is much more hydrophobic than in post-exponential cultures (Seeger et al., 2010).

In general, L. pneumophila LPS plays a crucial role in interaction with host cells and modulation of intracellular trafficking, independently of the Dot/Icm secretion system. The unusual structure of lipid A might help the bacteria to avoid recognition by the innate immune system.

Flagella and pili

The first evidence of the presence of flagella and pili structures on the L. pneumophila surface was provided by Rodgers et al. (1980). The authors were also the first to observe that pili of L. pneumophila vary in length. Later the pili were divided into long (0.8–1.5 μm) and short (0.1–0.6 μm) forms (Stone and Abu Kwaik, 1998). The PilE protein is the constituent of long type IV pili. It is involved in attachment and adherence to host cells as well as natural competence of L. pneumophila. At the same time a mutation in the pilE gene does not affect the intracellular survival and replication of bacteria (Stone and Abu Kwaik, 1998; Stone and Kwaik, 1999).

Another protein responsible for type IV pili production is the prepilin peptidase PilD. Unlike PilE, PilD is important for successful intracellular proliferation. This protein is also involved in type II secretion activity (Aragon et al., 2000). Both mentioned pili proteins facilitate the formation of biofilms of L. pneumophila (Lucas et al., 2006). Interestingly, despite microscopic evidence for the presence of the pili in liquid culture, some fimbrial synthesis genes are induced only in host cells (Bruggemann et al., 2006).

Additionally to pili, L. pneumophila exhibits a single monopolar flagellum, which is anchored within both membranes (OM, IM) and peptidoglycan by the basal body. This organelle plays an important role in cell motility, adhesion, and host invasion. It has also been described to be involved in biofilm formation (Heuner and Albert-Weissenberger, 2008). The expression of flagella is influenced by many environmental factors and is controlled by a hierarchical cascade of regulators (Albert-Weissenberger et al., 2010). The transition of the bacteria to the transmissive phase is co-regulated with the expression of flagella. Regulators that control flagellation also control important virulence traits such as lysosome avoidance and cytotoxicity (Gabay et al., 1986; Byrne and Swanson, 1998; Molofsky et al., 2005). On the other hand cytosolic flagellin is described to trigger the macrophage response to a L. pneumophila infection. This mechanism is mediated by Naip5/Birc1e, a member of the NLR family. It activates the caspase-1-dependent cell-death pathway that restricts bacterial growth (Molofsky et al., 2006; Ren et al., 2006). Information on the L. pneumophila flagellum is excellently reviewed in a recent publication (Heuner and Albert-Weissenberger, 2008).

Outer membrane vesicles

Outer membrane vesicles are shed from the outer membrane by L. pneumophila and most other Gram-negative bacteria. They are between 100 and 250 nm in diameter and consist of components from the outer membrane, including LPS, and the periplasm (Figure 3). L. pneumophila OMVs contain a disproportionately high number of virulence-associated proteins and display lipolytic and proteolytic activities (Galka et al., 2008).

Figure 3.

Electron micrographs of L. pneumophila and outer membrane vesicles. L. pneumophila sheds OMVs (arrows) from its surface during growth in liquid media (A) and within phagosomes of Dictyostelium discoideum (B).

In general, OMVs from other bacteria can mediate interbacterial contact and also the contact to eukaryotic cells. They can kill other bacteria by the delivery of harmful factors. Macromolecule-degrading enzymes in association with OMVs can promote nutrient acquisition, i.e., by cleaving proteins into amino acids which are then taken up by the bacterium. Modulations of biofilm formation and quorum sensing functions have also been assigned to OMVs. In the interaction with eukaryotic host cells, OMVs can deliver toxins and other virulence factors and have been shown to adhere to cell surfaces. In addition, the immune response – cytokine profiles, inflammation, innate immunity – is modified by contact to bacterial OMVs (Ellis and Kuehn, 2010).

So far, OMVs of L. pneumophila have been studied to a lower extent. A proteomic analysis revealed 74 different proteins. The export of 33 of these proteins occurs only via OMVs, but not individually via type II, III, or IV secretion systems. Of these OMV-specific proteins, 18 are reported or predicted to contribute to pathogenesis and virulence (Galka et al., 2008). This finding led to the conclusion that L. pneumophila employs OMVs as vehicles for the transport of virulence factors toward the environment.

The exact mode of interaction of L. pneumophila OMVs and host cell surfaces remains to be elucidated. However, an association of OMVs to the cytoplasmic membrane of human alveolar epithelial cells has been shown. The contact between OMVs and the cells resulted in a change in cell morphology, leading to round cells (Galka et al., 2008).

Outer membrane vesicles can also elicit a specific cytokine response from alveolar epithelial cells, resulting in the release of interleukins-6, -7, -8, and -13 as well as G-CSF, IFN-γ, and MCP-1. IL-7 and IL-8 are secreted only after stimulation with OMVs, but not after stimulation with individually secreted proteins.

Legionella pneumophila OMVs increase the growth of Acanthamoeba castellanii over the course of 72 h, rather than damaging the host cells (Galka et al., 2008). As A. castellanii usually feeds on bacteria, membrane vesicles are thought to serve as a source of nutrients, possibly to attract amoeba toward bacteria, which then infect them.

Latex beads which have been coated with L. pneumophila OMVs can inhibit the fusion of Legionella-containing phagosomes to lysosomes, thereby preventing death of the bacteria (Fernandez-Moreira et al., 2006). This key feature of Legionella infections seems to be mediated by OMVs, at least to a certain degree. The LPS on the surface of OMVs is regulated similarly to LPS on the outer membrane. The phagolysosomal arrest is evoked more strongly by soluble LPS shed into the bacterial surrounding. The arrest efficiency seems to decrease over time (Seeger et al., 2010).

The inhibition of the fusion between phagosomes and lysosomes is only one of the functions of L. pneumophila OMVs. They also display proteolytic and lipolytic activities, though the fraction of individually secreted proteins features stronger degradative enzyme activities (Galka et al., 2008). In this way, OMVs might contribute to the dissemination of the infection across tissue barriers such as the alveolar epithelium.

In conclusion, OMVs are believed to be a vehicle for the transport of virulence factors to distant cells or host tissues. Their precise contribution to L. pneumophila infections has not been determined yet, but is under investigation.

Conclusion

Legionella pneumophila inhabits fresh waters and biofilms. Moreover, this pathogen parasitizes phylogenetically distant hosts such as protozoa and human cells, a process which requires adhesion, invasion, and interactions within the phagosome. Under all these conditions the bacterial cell envelope is the prime structure through which L. pneumophila interacts with these fundamentally different environments. Although the potential properties of the cell envelope are ultimately determined by the information stored within the genome, it becomes increasingly evident that molecular identities, spatial distributions, and biochemical activities of many envelope constituents are highly dynamic and vary with L. pneumophila growth phases, developmental differentiation processes as well as during the pathogen–host interaction. Therefore, the investigation of phenotypic changes, which take place as the bacteria adapt to different conditions, holds great promise for the understanding of this pathogen. Proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids in the bacterial cell envelope serve both structural and signaling roles, but until recently the main focus of biomedical research was on identification and analysis of proteins. Hereby we have learned that already characterized proteins can have unexpected functions, suggesting the need for more thorough investigations. Based on the current body of information there is also increased awareness that lipids, both of host and bacterial origin, choreograph pathogen stability and host susceptibility to infection. The renewed interest in these historically neglected effector molecules is currently fueled by the advances in lipidomics and glycomics technologies. Thus, identification of unique lipid entities and their biological activities represent an enormously promising new frontier in the infection biology of L. pneumophila.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). Jens Jäger is supported by the Foundation of German Business (Stiftung der Deutschen Wirtschaft). The authors would like to thank Simon Döhrmann for help with the images.

References

- Akira S., Takeda K., Kaisho T. (2001). Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2, 675–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albers U., Tiaden A., Spirig T., Al Alam D., Goyert S. M., Gangloff S. C., Hilbi H. (2007). Expression of Legionella pneumophila paralogous lipid A biosynthesis genes under different growth conditions. Microbiology 153, 3817–3829 10.1099/mic.0.2007/009829-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert-Weissenberger C., Sahr T., Sismeiro O., Hacker J., Heuner K., Buchrieser C. (2010). Control of flagellar gene regulation in Legionella pneumophila and its relation to growth phase. J. Bacteriol. 192, 446–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khodor S., Kalachikov S., Morozova I., Price C. T., Abu Kwaik Y. (2009). The PmrA/PmrB two-component system of Legionella pneumophila is a global regulator required for intracellular replication within macrophages and protozoa. Infect. Immun. 77, 374–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano K., Williams J. C. (1983). Peptidoglycan of Legionella pneumophila: apparent resistance to lysozyme hydrolysis correlates with a high degree of peptide cross-linking. J. Bacteriol. 153, 520–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragon V., Kurtz S., Flieger A., Neumeister B., Cianciotto N. P. (2000). Secreted enzymatic activities of wild-type and pilD-deficient Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 68, 1855–1863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay P., Byrne B., Chan Y., Swanson M. S., Steinman H. M. (2003). Legionella pneumophila catalase-peroxidases are required for proper trafficking and growth in primary macrophages. Infect. Immun. 71, 4526–4535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerji S., Aurass P., Flieger A. (2008). The manifold phospholipases A of Legionella pneumophila – identification, export, regulation, and their link to bacterial virulence. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 298, 169–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker J., Lambert P. A., Brown M. R. (1993). Influence of intra- amoebic and other growth conditions on the surface properties of Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 61, 3503–3510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger-Kawahara C., Horwitz M. A. (1990). Complement component C3 fixes selectively to the major outer membrane protein (MOMP) of Legionella pneumophila and mediates phagocytosis of liposome-MOMP complexes by human monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 172, 1201–1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop R. E., Gibbons H. S., Guina T., Trent M. S., Miller S. I., Raetz C. R. (2000). Transfer of palmitate from phospholipids to lipid A in outer membranes of Gram-negative bacteria. EMBO J. 19, 5071–5080 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruggemann H., Hagman A., Jules M., Sismeiro O., Dillies M. A., Gouyette C., Kunst F., Steinert M., Heuner K., Coppee J. Y., Buchrieser C. (2006). Virulence strategies for infecting phagocytes deduced from the in vivo transcriptional program of Legionella pneumophila. Cell. Microbiol. 8, 1228–1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne B., Swanson M. S. (1998). Expression of Legionella pneumophila virulence traits in response to growth conditions. Infect. Immun. 66, 3029–3034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazalet C., Jarraud S., Ghavi-Helm Y., Kunst F., Glaser P., Etienne J., Buchrieser C. (2008). Multigenome analysis identifies a worldwide distributed epidemic Legionella pneumophila clone that emerged within a highly diverse species. Genome Res. 18, 431–441 10.1101/gr.7229808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianciotto N. P. (2007). Iron acquisition by Legionella pneumophila. Biometals 20, 323–331 10.1007/s10534-006-9057-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianciotto N. P. (2009). Many substrates and functions of type II secretion: lessons learned from Legionella pneumophila. Future Microbiol. 4, 797–805 10.2217/fmb.09.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielski C. A., Blaser M. J., Wang W. L. (1986). Serogroup specificity of Legionella pneumophila is related to lipopolysaccharide characteristics. Infect Immun. 51, 397–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirillo S. L., Lum J., Cirillo J. D. (2000). Identification of novel loci involved in entry by Legionella pneumophila. Microbiology 146(Pt 6), 1345–1359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conover G. M., Martinez-Morales F., Heidtman M. I., Luo Z. Q., Tang M., Chen C., Geiger O., Isberg R. R. (2008). Phosphatidylcholine synthesis is required for optimal function of Legionella pneumophila virulence determinants. Cell. Microbiol. 10, 514–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debroy S., Aragon V., Kurtz S., Cianciotto N. P. (2006). Legionella pneumophila Mip, a surface-exposed peptidylproline cis-trans-isomerase, promotes the presence of phospholipase C-like activity in culture supernatants. Infect. Immun. 74, 5152–5160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerrler W. T., Gibbons H. S., Raetz C. R. (2004). MsbA-dependent translocation of lipids across the inner membrane of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45102–45109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doleans A., Aurell H., Reyrolle M., Lina G., Freney J., Vandenesch F., Etienne J., Jarraud S. (2004). Clinical and environmental distributions of Legionella strains in France are different. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 458–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis T. N., Kuehn M. J. (2010). Virulence and immunomodulatory roles of bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74, 81–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner G., Garduño R. A. (2002). Ultrastructural analysis of differentiation in Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 184, 7025–7041 10.1128/JB.184.24.7025-7041.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Moreira E., Helbig J. H., Swanson M. S. (2006). Membrane vesicles shed by Legionella pneumophila inhibit fusion of phagosomes with lysosomes. Infect. Immun. 74, 3285–3295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerty W. R., Makula R. A., Feeley J. C. (1979). Cellular lipids of the Legionnaires’ disease bacterium. Ann. Intern. Med. 90, 631–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay J. E., Blake M., Niles W. D., Horwitz M. A. (1985). Purification of Legionella pneumophila major outer membrane protein and demonstration that it is a porin. J. Bacteriol. 162, 85–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay J. E., Horwitz M. A. (1985). Isolation and characterization of the cytoplasmic and outer membranes of the Legionnaires’ disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila). J. Exp. Med. 161, 409–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay J. E., Horwitz M. A., Cohn Z. A. (1986). Phagosome-lysosome fusion. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 14, 256–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galka F., Wai S. N., Kusch H., Engelmann S., Hecker M., Schmeck B., Hippenstiel S., Uhlin B. E., Steinert M. (2008). Proteomic characterization of the whole secretome of Legionella pneumophila and functional analysis of outer membrane vesicles. Infect. Immun. 76, 1825–1836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garduño R. A., Garduño E., Hoffman P. S. (1998). Surface-associated hsp60 chaperonin of Legionella pneumophila mediates invasion in a HeLa cell model. Infect. Immun. 66, 4602–4610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons H. S., Kalb S. R., Cotter R. J., Raetz C. R. (2005). Role of Mg2 + and pH in the modification of Salmonella lipid A after endocytosis by macrophage tumour cells. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 425–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard R., Pedron T., Uematsu S., Balloy V., Chignard M., Akira S., Chaby R. (2003). Lipopolysaccharides from Legionella and Rhizobium stimulate mouse bone marrow granulocytes via Toll-like receptor 2. J. Cell. Sci. 116, 293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin F., Duval J. F., Simonet J., Ginevra C., Gaboriaud F., Jarraud S., Mathieu L. (2010). Impact of the virulence-associated MAb3/1 epitope on the physicochemical surface properties of Legionella pneumophila sg1: an issue to explain infection potential? Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 82, 283–290 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.08.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn J. S., Lim K. B., Krueger J., Kim K., Guo L., Hackett M., Miller S. I. (1998). PmrA-PmrB-regulated genes necessary for 4-aminoarabinose lipid A modification and polymyxin resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 27, 1171–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Lim K. B., Gunn J. S., Bainbridge B., Darveau R. P., Hackett M., Miller S. I. (1997). Regulation of lipid A modifications by Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes phoP-phoQ. Science 276, 250–253 10.1126/science.276.5310.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Lim K. B., Poduje C. M., Daniel M., Gunn J. S., Hackett M., Miller S. I. (1998). Lipid A acylation and bacterial resistance against vertebrate antimicrobial peptides. Cell 95, 189–198 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81750-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M., Yang K., Hashimoto M., Park J. H., Kim Y. G., Fujimoto Y., Nunez G., Fukase K., Inohara N. (2006). Differential release and distribution of Nod1 and Nod2 immunostimulatory molecules among bacterial species and environments. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 29054–29063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawn T. R., Verbon A., Janer M., Zhao L. P., Beutler B., Aderem A. (2005). Toll-like receptor 4 polymorphisms are associated with resistance to Legionnaires’ disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 2487–2489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helbig J. H., Amemura-Maekawa J. (2009). Serotyping of Legionella pneumophila and epidemiological investigations. Nowa Medycyna 16, 69–75 [Google Scholar]

- Helbig J. H., Bernander S., Castellani Pastoris M., Etienne J., Gaia V., Lauwers S., Lindsay D., Lück P. C., Marques T., Mentula S., Peeters M. F., Pelaz C., Struelens M., Uldum S. A., Wewalka G., Harrison T. G. (2002). Pan-European study on culture-proven Legionnaires’ disease: distribution of Legionella pneumophila serogroups and monoclonal subgroups. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 21, 710–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helbig J. H., Lück P. C., Knirel Y. A., Witzleb W., Zähringer U. (1995). Molecular characterization of a virulence-associated epitope on the lipopolysaccharide of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1. Epidemiol. Infect. 115, 71–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuner K., Albert-Weissenberger C. (2008). Legionella Molecular Biology. Norfolk: Caister Academic Press; 17888731 [Google Scholar]

- Heuner K., Steinert M. (2003). The flagellum of Legionella pneumophila and its link to the expression of the virulent phenotype. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 293, 133–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindahl M. S., Iglewski B. H. (1984). Isolation and characterization of the Legionella pneumophila outer membrane. J. Bacteriol. 159, 107–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman P. S., Garduño R. A. (1999). Surface-associated heat shock proteins of Legionella pneumophila and Helicobacter pylori: roles in pathogenesis and immunity. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 7, 58–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovel-Miner G., Pampou S., Faucher S. P., Clarke M., Morozova I., Morozov P., Russo J. J., Shuman H. A., Kalachikov S. (2009). SigmaS controls multiple pathways associated with intracellular multiplication of Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 191, 2461–2473 10.1128/JB.01578-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubber A., Roy C. R. (2010). Modulation of host cell function by Legionella pneumophila type IV effectors. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 26, 261–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston W. M., Naylor J., Cianciotto N. P., Jennings M. P., McEwan A. G. (2008). Functional analysis of the multi-copper oxidase from Legionella pneumophila. Microbes Infect. 10, 497–503 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki K., Ernst R. K., Miller S. I. (2004). 3-O-deacylation of lipid A by PagL, a PhoP/PhoQ-regulated deacylase of Salmonella typhimurium, modulates signaling through Toll-like receptor 4. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 20044–20048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khemiri A., Galland A., Vaudry D., Chan Tchi Song P., Vaudry H., Jouenne T., Cosette P. (2008). Outer-membrane proteomic maps and surface-exposed proteins of Legionella pneumophila using cellular fractionation and fluorescent labelling. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 390, 1861–1871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. J., Sohn J. W., Park D. W., Park S. C., Chun B. C. (2003). Characterization of a lipoprotein common to Legionella species as a urinary broad-spectrum antigen for diagnosis of Legionnaires’ disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 2974–2979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knirel Y. A., Moll H., Helbig J. H., Zähringer U. (1997). Chemical characterization of a new 5,7-diamino-3,5,7,9-tetradeoxynonulosonic acid released by mild acid hydrolysis of the Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 lipopolysaccharide. Carbohydr. Res. 304, 77–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knirel Y. A., Moll H., Zähringer U. (1996). Structural study of a highly O-acetylated core of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 lipopolysaccharide. Carbohydr. Res. 293, 223–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knirel Y. A., Rietschel E. T., Marre R., Zähringer U. (1994). The structure of the O-specific chain of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 lipopolysaccharide. Eur. J. Biochem. 221, 239–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooistra O., Herfurth L., Lüneberg E., Frosch M., Peters T., Zähringer U. (2002a). Epitope mapping of the O-chain polysaccharide of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 lipopolysaccharide by saturation-transfer-difference NMR spectroscopy. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 573–582 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02684.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooistra O., Lüneberg E., Knirel Y. A., Frosch M., Zähringer U. (2002b). N-methylation in polylegionaminic acid is associated with the phase-variable epitope of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 lipopolysaccharide. Identification of 5-(N,N-dimethylacetimidoyl)amino and 5-acetimidoyl(N-methyl)amino-7-acetamido-3,5,7,9-tetradeoxynon-2-ulosonic acid in the O-chain polysaccharide. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 560–572 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02683.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krinos C., High A. S., Rodgers F. G. (1999). Role of the 25 kDa major outer membrane protein of Legionella pneumophila in attachment to U-937 cells and its potential as a virulence factor for chick embryos. J. Appl. Microbiol. 86, 237–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammertyn E., Anne J. (2004). Protein secretion in Legionella pneumophila and its relation to virulence. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 238, 273–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liles M. R., Viswanathan V. K., Cianciotto N. P. (1998). Identification and temperature regulation of Legionella pneumophila genes involved in type IV pilus biogenesis and type II protein secretion. Infect. Immun. 66, 1776–1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas C. E., Brown E., Fields B. S. (2006). Type IV pili and type II secretion play a limited role in Legionella pneumophila biofilm colonization and retention. Microbiology 152, 3569–3573 10.1099/mic.0.2006/000497-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüneberg E., Mayer B., Daryab N., Kooistra O., Zähringer U., Rohde M., Swanson J., Frosch M. (2001). Chromosomal insertion and excision of a 30 kb unstable genetic element is responsible for phase variation of lipopolysaccharide and other virulence determinants in Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 39, 1259–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüneberg E., Zähringer U., Knirel Y. A., Steinmann D., Hartmann M., Steinmetz I., Rohde M., Köhl J., Frosch M. (1998). Phase-variable expression of lipopolysaccharide contributes to the virulence of Legionella pneumophila. J. Exp. Med. 188, 49–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüneberg E., Zetzmann N., Alber D., Knirel Y. A., Kooistra O., Zähringer U., Frosch M. (2000). Cloning and functional characterization of a 30 kb gene locus required for lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Legionella pneumophila. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 290, 37–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma B., Reynolds C. M., Raetz C. R. (2008). Periplasmic orientation of nascent lipid A in the inner membrane of an Escherichia coli LptA mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 13823–13828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews M., Roy C. R. (2000). Identification and subcellular localization of the Legionella pneumophila IcmX protein: a factor essential for establishment of a replicative organelle in eukaryotic host cells. Infect. Immun. 68, 3971–3982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merault N., Rusniok C., Jarraud S., Gomez-Valero L., Cazalet C., Marin M., Brachet E., Aegerter P., Gaillard J. L., Etienne J., Herrmann J. L., DELPH-I Study Group. Lawrence C., Buchrieser C. (2010). A specific real-time PCR for simultaneous detection and identification of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 in water and clinical samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 1708–1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. I., Kukral A. M., Mekalanos J. J. (1989). A two-component regulatory system (phoP phoQ) controls Salmonella typhimurium virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 5054–5058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz C. S., Arnold P. I., Johnson W., Schultz D. R. (1995). Antibody-independent binding of complement component C1q by Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 63, 4939–4943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz C. S., Schultz D. R., Arnold P. I., Johnson W. (1992). Legionella pneumophila lipopolysaccharide activates the classical complement pathway. Infect. Immun. 60, 2769–2776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll H., Knirel Y. A., Helbig J. H., Zähringer U. (1997). Identification of an alpha-D-Manp-(1 → 8)-Kdo disaccharide in the inner core region and the structure of the complete core region of the Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 lipopolysaccharide. Carbohydr. Res. 304, 91–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll H., Sonesson A., Jantzen E., Marre R., Zähringer U. (1992). Identification of 27-oxo-octacosanoic acid and heptacosane-1,27-dioic acid in Legionella pneumophila. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 76, 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molofsky A. B., Byrne B. G., Whitfield N. N., Madigan C. A., Fuse E. T., Tateda K., Swanson M. S. (2006). Cytosolic recognition of flagellin by mouse macrophages restricts Legionella pneumophila infection. J. Exp. Med. 203, 1093–1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molofsky A. B., Shetron-Rama L. M., Swanson M. S. (2005). Components of the Legionella pneumophila flagellar regulon contribute to multiple virulence traits, including lysosome avoidance and macrophage death. Infect. Immun. 73, 5720–5734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano N., Kubori T., Kinoshita M., Imada K., Nagai H. (2010). Crystal structure of Legionella DotD: insights into the relationship between type IVB and type II/III secretion systems. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001129. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoli C., Fasano F., Iatta R., Barbuti G., Cuna T., Montagna M. T. (2010). Legionella spp. and legionellosis in southeastern Italy: disease epidemiology and environmental surveillance in community and health care facilities. BMC Public Health 10, 660. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumeister B., Faigle M., Sommer M., Zähringer U., Stelter F., Menzel R., Schütt C., Northoff H. (1998). Low endotoxic potential of Legionella pneumophila lipopolysaccharide due to failure of interaction with the monocyte lipopolysaccharide receptor CD14. Infect. Immun. 66, 4151–4157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton H. J., Sansom F. M., Dao J., Cazalet C., Bruggemann H., Albert-Weissenberger C., Buchrieser C., Cianciotto N. P., Hartland E. L. (2008). Significant role for ladC in initiation of Legionella pneumophila infection. Infect. Immun. 76, 3075–3085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninio S., Roy C. R. (2007). Effector proteins translocated by Legionella pneumophila: strength in numbers. Trends Microbiol. 15, 372–380 10.1016/j.tim.2007.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palusinska-Szysz M., Janczarek M., Kalitynski R., Dawidowicz A. L., Russa R. (2011). Legionella bozemanae synthesizes phosphatidylcholine from exogenous choline. Microbiol. Res. 166, 87–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palusinska-Szysz M., Russa R. (2009). Chemical structure and biological significance of lipopolysaccharide from Legionella. Recent Pat. Antiinfect. Drug. Discov. 4, 96–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petermann N., Hansen G., Schmidt C. L., Hilgenfeld R. (2010). Structure of the GTPase and GDI domains of FeoB, the ferrous iron transporter of Legionella pneumophila. FEBS Lett. 584, 733–738 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasis M., Segal G. (2009). The LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade, together with RpoS and PmrA, post-transcriptionally regulates stationary phase activation of Legionella pneumophila Icm/Dot effectors. Mol. Microbiol. 72, 995–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren T., Zamboni D. S., Roy C. R., Dietrich W. F., Vance R. E. (2006). Flagellin-deficient Legionella mutants evade caspase-1- and Naip5-mediated macrophage immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2, e18. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riboldi-Tunnicliffe A., Konig B., Jessen S., Weiss M. S., Rahfeld J., Hacker J., Fischer G., Hilgenfeld R. (2001). Crystal structure of Mip, a prolylisomerase from Legionella pneumophila. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 779–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robey M., Cianciotto N. P. (2002). Legionella pneumophila feoAB promotes ferrous iron uptake and intracellular infection. Infect. Immun. 70, 5659–5669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robey M., O'Connell W., Cianciotto N. P. (2001). Identification of Legionella pneumophila rcp, a pagP-like gene that confers resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides and promotes intracellular infection. Infect. Immun. 69, 4276–4286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers F. G., Davey M. R. (1982). Ultrastructure of the cell envelope layers and surface details of Legionella pneumophila. J. Gen. Microbiol. 128, 1547–1557 10.1099/00221287-128-7-1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers F. G., Greaves P. W., Macrae A. D., Lewis M. J. (1980). Electron microscopic evidence of flagella and pili on Legionella pneumophila. J. Clin. Pathol. 33, 1184–1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J., Hakki A., Perkins I., Newton C., Widen R., Burdash N., Klein T., Friedman H. (2007). Legionella pneumophila infection up-regulates dendritic cell Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2)/TLR4 expression and key maturation markers. Infect. Immun. 75, 3205–3208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossier O., Cianciotto N. P. (2005). The Legionella pneumophila tatB gene facilitates secretion of phospholipase C, growth under iron-limiting conditions, and intracellular infection. Infect. Immun. 73, 2020–2032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaran K., Wu H. C. (1994). Lipid modification of bacterial prolipoprotein. Transfer of diacylglyceryl moiety from phosphatidylglycerol. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 19701–19706 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada K., Ariki S., Kojima T., Saito A., Yamazoe M., Nishitani C., Shimizu T., Takahashi M., Mitsuzawa H., Yokota S., Sawada N., Fujii N., Takahashi H., Kuroki Y. (2010). Pulmonary collectins protect macrophages against pore-forming activity of Legionella pneumophila and suppress its intracellular growth. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 8434–8443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell S., Steinman H. M. (1995). Function and stationary-phase induction of periplasmic copper-zinc superoxide dismutase and catalase/peroxidase in Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 177, 5924–5929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schunder E., Adam P., Higa F., Remer K. A., Lorenz U., Bender J., Schulz T., Flieger A., Steinert M., Heuner K. (2010). Phospholipase PlaB is a new virulence factor of Legionella pneumophila. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 300, 313–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger E. M., Thuma M., Fernandez-Moreira E., Jacobs E., Schmitz M., Helbig J. H. (2010). Lipopolysaccharide of Legionella pneumophila shed in a liquid culture as a nonvesicular fraction arrests phagosome maturation in amoeba and monocytic host cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 307, 113–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim H. K., Kim J. Y., Kim M. J., Sim H. S., Park D. W., Sohn J. W., Kim M. J. (2009). Legionella lipoprotein activates toll-like receptor 2 and induces cytokine production and expression of costimulatory molecules in peritoneal macrophages. Exp. Mol. Med. 41, 687–694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silhavy T. J., Kahne D., Walker S. (2010). The bacterial cell envelope. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderberg M. A., Cianciotto N. P. (2010). Mediators of lipid A modification, RNA degradation, and central intermediary metabolism facilitate the growth of Legionella pneumophila at low temperatures. Curr. Microbiol. 60, 59–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohlenkamp C., Lopez-Lara I. M., Geiger O. (2003). Biosynthesis of phosphatidylcholine in bacteria. Prog. Lipid Res. 42, 115–162 10.1016/S0163-7827(02)00050-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St John G., Steinman H. M. (1996). Periplasmic copper-zinc superoxide dismutase of Legionella pneumophila: role in stationary-phase survival. J. Bacteriol. 178, 1578–1584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone B. J., Abu Kwaik Y. (1998). Expression of multiple pili by Legionella pneumophila: identification and characterization of a type IV pilin gene and its role in adherence to mammalian and protozoan cells. Infect. Immun. 66, 1768–1775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone B. J., Kwaik Y. A. (1999). Natural competence for DNA transformation by Legionella pneumophila and its association with expression of type IV pili. J. Bacteriol. 181, 1395–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandersmissen L., De Buck E., Saels V., Coil D. A., Anne J. (2010). A Legionella pneumophila collagen-like protein encoded by a gene with a variable number of tandem repeats is involved in the adherence and invasion of host cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 306, 168–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdon J., Labanowski J., Sahr T., Ferreira T., Lacombe C., Buchrieser C., Berjeaud J. M., Héchard Y. (2011). Fatty acid composition modulates sensitivity of Legionella pneumophila to warnericin RK, an antimicrobial peptide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1808, 1146–1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan V. K., Edelstein P. H., Pope C. D., Cianciotto N. P. (2000). The Legionella pneumophila iraAB locus is required for iron assimilation, intracellular infection, and virulence. Infect. Immun. 68, 1069–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner C., Khan A. S., Kamphausen T., Schmausser B., ünal C., Lorenz U., Fischer G., Hacker J., Steinert M. (2007). Collagen binding protein Mip enables Legionella pneumophila to transmigrate through a barrier of NCI-H292 lung epithelial cells and extracellular matrix. Cell. Microbiol. 9, 450–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Quinn P. J. (2010). Lipopolysaccharide: biosynthetic pathway and structure modification. Prog. Lipid Res. 49, 97–107 10.1016/j.plipres.2009.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yerushalmi G., Zusman T., Segal G. (2005). Additive effect on intracellular growth by Legionella pneumophila Icm/Dot proteins containing a lipobox motif. Infect. Immun. 73, 7578–7587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zähringer U., Knirel Y. A., Lindner B., Helbig J. H., Sonesson A., Marre R., Rietschel E. T. (1995). The lipopolysaccharide of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 (strain Philadelphia 1): chemical structure and biological significance. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 392, 113–139 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]