Abstract

Day respiration (Rd) is an important parameter in leaf ecophysiology. It is difficult to measure directly and is indirectly estimated from gas exchange (GE) measurements of the net photosynthetic rate (A), commonly using the Laisk method or the Kok method. Recently a new method was proposed to estimate Rd indirectly from combined GE and chlorophyll fluorescence (CF) measurements across a range of low irradiances. Here this method is tested for estimating Rd in five C3 and one C4 crop species. Values estimated by this new method agreed with those by the Laisk method for the C3 species. The Laisk method, however, is only valid for C3 species and requires measurements at very low CO2 levels. In contrast, the new method can be applied to both C3 and C4 plants and at any CO2 level. The Rd estimates by the new method were consistently somewhat higher than those by the Kok method, because using CF data corrects for errors due to any non-linearity between A and irradiance of the used data range. Like the Kok and Laisk methods, the new method is based on the assumption that Rd varies little with light intensity, which is still subject to debate. Theoretically, the new method, like the Kok method, works best for non-photorespiratory conditions. As CF information is required, data for the new method are usually collected using a small leaf chamber, whereas the Kok and Laisk methods use only GE data, allowing the use of a larger chamber to reduce the noise-to-signal ratio of GE measurements.

Keywords: Kok effect, mitochondrial respiration in the light, photosynthesis models

Introduction

Non-photorespiratory CO2 release in the light, also known as ‘day respiration’ (Rd; Azcon-Bieto et al., 1981), is an important parameter in modelling net rate of leaf photosynthesis. Unlike the respiratory CO2 release in the dark (Rdk), Rd is difficult to measure directly in vivo because of the flux from simultaneous photosynthetic carbon fixation and photorespiration (Ribas-Carbo et al., 2010). Direct measurement of Rd requires sophisticated methodologies, exploiting the different time course of labelling by carbon isotopes of photosynthetic, photorespiratory, and respiratory pathways (e.g. Haupt-Herting et al., 2001; Loreto et al., 2001; Pinelli and Loreto, 2003; Pärnik and Keerberg, 2007). For leaf ecophysiological studies, usually Rd is indirectly estimated from gas exchange (GE) measurements for net photosynthetic rate (A) by extrapolating the linear relationship between A and light intensity (Kok, 1948) or by identifying the intersection of the linear relationships of A versus the intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) assessed at several levels of irradiance (Laisk, 1977). Other indirect methods based on GE data have also been described (e.g. Laisk and Loreto, 1996; Peisker and Apel, 2001).

The Kok method (Kok, 1948) utilizes the fact that the response of A to light is generally linear at low irradiances. However, in the vicinity of the light compensation point there might be a break in the linear relationship, with a markedly higher slope of the response curve below than above the break point—the so-called ‘Kok-effect’ (Kok, 1948; Sharp et al., 1984; Brooks and Farquhar, 1985; Kirschbaum and Farquhar, 1987; Villar et al., 1994). Sharp et al. (1984) explained that the higher slope below the break was attributable to the effect of the suppression of dark respiration by light (see also Ribas-Carbo et al., 2010). To avoid the influence of the Kok effect, data of the linear range above the break point are analysed, and the extrapolation of that particular linear section of the curve to the zero irradiance gives an estimate of Rd (Brooks and Farquhar, 1985; Villar et al., 1994; Wang et al., 2001; Shapiro et al., 2004). The method can be applied to any CO2 level, and might be used to examine whether or not Rd varies with a change of the CO2 levels. Obviously, the method assumes that Rd does not vary with light within the range of light levels used.

The second method, described by Laisk (1977), analyses the response curves of A to low Ci that are obtained at several light intensities. It aims to identify the intercellular CO2 level (Ci*) at which the rate of CO2 fixation by photosynthesis equals the rate of CO2 release from photorespiration. At this Ci* (i.e. Ci-based CO2 compensation point in the absence of Rd), all of the fixed CO2 is consumed in photorespiration, and the rate of CO2 release should represent Rd. The values of Ci* and Rd are identified as the coordinates of the common intersection point of A versus Ci at two or more light intensities (Fig. 1a). Obviously, the Laisk method also assumes that Rd does not vary with irradiance within the irradiance ranges used. However, by using a wide array of irradiances, the method can be used to explore any effect of light intensity on the value of Rd (Villar et al., 1994). The main disadvantage of the Laisk method is that the measurements must be performed at very low CO2 levels and are therefore under far from normal environmental conditions, especially given that a change in Rd with CO2 level has been reported (Villar et al., 1994). Nevertheless, the Laisk method has been widely used as a standard method to estimate Rd (e.g. Brooks and Farquhar, 1985; von Caemmerer et al., 1994; Atkin et al., 1997, 2000; Peisker and Apel, 2001; Priault et al., 2006; Flexas et al., 2007b).

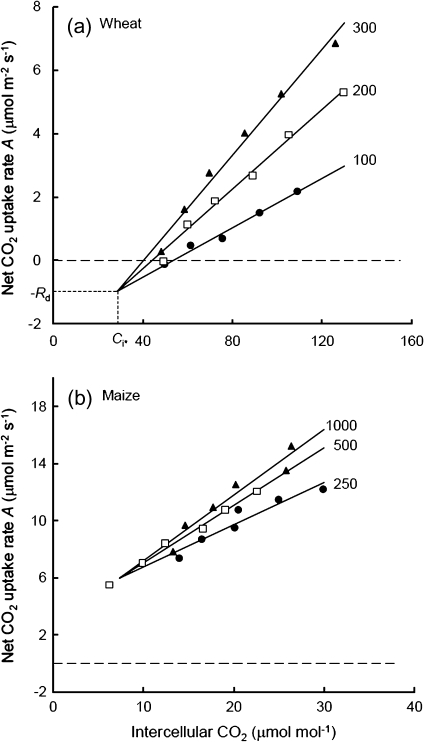

Fig. 1.

Net CO2 assimilation rate (A) as a function of intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci). Numbers indicate the three incident irradiances (Iinc) under which measurements were carried out (in μmol m−2 s−1). Regression lines at these Iinc, fitted to data points that each represents the mean of measurements from four replicated plants, were forced to join at the common intersection point (Ci*, –Rd), where Rd is the estimated leaf respiration rate in the light (Laisk method) and Ci* is the Ci-based CO2 compensation point in the absence of Rd. The dashed horizontal line is the line of A=0. The estimated Rd is negative for maize (b), indicating that the Laisk method does not work for C4 species. Note that the scales in the two panels are different.

Like GE measurements, chlorophyll fluorescence (CF) measurements have increasingly been used as a non-invasive tool in leaf ecophysiological studies. In particular when the two types of measurements are combined to assess both A and photosystem II (PSII) electron (e–) transport efficiency (Φ2) simultaneously, a number of photosynthesis parameters underlying physiological responses to environmental variables can be estimated (e.g. Laisk and Loreto, 1996). For example, combined GE and CF measurements have been used to estimate mesophyll conductance gm (Harley et al., 1992; Yin and Struik, 2009), relative CO2/O2 specificity of Rubisco (Peterson, 1989), inter-photosystem excitation partitioning factor, and alternative e– transport (Makino et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2006). However, combined GE and CF measurements have hardly been used to estimate Rd. The only report is a recent integrated method of using these combined data to estimate photosynthesis parameters (including Rd) of a biochemical C3 photosynthesis model (Yin et al., 2009). Like the Kok method, this method utilizes the response of A to irradiance at low light intensities. However, this method also utilizes the CF information on the response of Φ2 to light. Preliminary results for wheat (Triticum aestivum) leaves have shown that the new CF-based method allows a better estimate of Rd than the Kok method does (Yin et al., 2009).

In the present work, this novel CF-based method is compared not only with the Kok method but also with the more widely used Laisk method, in estimating Rd of leaves in various crop species. The specific emphasis is placed on examining whether the CF-based method is generally applicable.

Materials and methods

Theoretical considerations

The method of Yin et al. (2009) to estimate Rd is based on the fact that at low values of irradiance A is limited by the light-dependent e– transport rate. Building upon the well-known model of Farquhar et al. (1980), Yin et al. (2004) described a generalized equation for A within the e– transport-limited range as:

| (1) |

where J2 is the total rate of e– transport passing PSII, fcyc and fpseudo represent fractions of the total e– flux passing PSI that follow cyclic and pseudocyclic pathways, respectively, Cc is the CO2 level at the carboxylation sites of Rubisco, and Γ* is the Cc-based CO2 compensation point in the absence of Rd. A special case of Equation (1) is the e– transport-limited equation of the Farquhar et al. (1980) model:

| (2) |

where J is the PSII e– transport rate that is used for CO2 fixation and photorespiration.

By definition, the variable J2 in Equation (1) can be replaced by ρ2βIincΦ2, where Iinc is the level of incident irradiance, β is the absorptance by leaf photosynthetic pigments, and ρ2 is the fraction of absorbed irradiance partitioned to PSII. Substituting this term into Equation (1) gives:

| (3) |

For non-photorespiratory conditions where Cc approaches infinity and/or Γ* approaches zero, Equation (3) becomes:

| (4) |

where the lumped parameter s=ρ2β[1–fpseudo/(1–fcyc)]. So, using data of the e– transport-limited range under non-photorespiratory conditions, a simple linear regression can be performed for the observed A against (IincΦ2/4), in which Φ2 is based on CF measurements. The slope of the regression will yield the estimate of a lumped parameter s, and the intercept will give an estimate of Rd (Yin et al., 2009). Clearly, this CF-based method is very similar to the Kok method; therefore, it should apply to the range of limiting irradiances, yet above the Kok break point if the Kok effect occurs. However, the Kok method has an additional assumption that Φ2 is constant within the range of limiting lights. As will be shown later, this assumption is not true.

Assuming the variation of the term (Cc–Γ*)/(Cc+2Γ*) in Equation (3) is negligible across an A–Iinc curve, Yin et al. (2009) showed that the simple regression procedure can also be used to estimate Rd for photorespiratory conditions, although it is then less certain that the relationship between A and IincΦ2/4 will be linear. This assumption is in fact also used implicitly in applying the Kok method to estimate Rd or quantum yield under photorespiratory conditions. To correct for small differences of CO2 level across an A–Iinc curve when estimating Rd, a procedure as proposed by Kirschbaum and Farquhar (1987) would need to be implemented. However, their correction procedure was based on an assumption of infinite gm, which is now known to be unlikely to be true (Harley et al., 1992; Flexas et al., 2007b; Yin and Struik, 2009). A full correction would require a pre- or simultaneous estimation of gm, in addition to the estimation of Γ*. No correction was therefore made in using the CF method for the purpose of simplicity.

Plant material and measurements

Five C3 crop species, wheat (cv. ‘Lavett’), rice (Oryza sativa, cv. ‘IR64’), potato (Solanum tuberosum, cv. ‘Bintje’), tomato (an inbred line from a cross between Solanum lycopersicum cv. ‘Moneyberg’ and Solanum chmielewskii), and rose (Rosa hybrida cv. ‘Akito’), and one C4 species (Zea mays, experimental hybrid ‘2-05R00061’) were chosen for this study. Plants were grown in a glasshouse complex, in pot soil (wheat, rice, potato, and maize) or on rock-wool hydroponics (tomato and rose), without water or nutrient stress. Climatic conditions in the glasshouses were semi-controlled. Extra SON-T light was switched on when solar radiation outside the glasshouses was <400 W m−2. The glasshouse [CO2] was ∼370 μmol mol−1, relative humidity was 60–80%, and temperature was 25±5 °C during measurements.

An open GE system (Li-Cor 6400; Li-Cor Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) and an integrated fluorescence chamber head (i.e. the 2 cm2 chamber) were used. While the Laisk and Kok methods require only GE measurements, data would be collected by using the larger 6 cm2 chamber to reduce GE measurement noises. However, for comparison of the three methods, all the data were collected using the 2 cm2 chamber. All measurements were carried out at a leaf temperature of 25 °C and a leaf-to-air vapour pressure difference of 1.0–1.6 kPa, using a flow rate of 400 μmol s−1. Each measurement was made on four full-grown leaves in replicated plants.

Two sets of measurements were conducted. The first set was to compare the three methods. For Ci response curves required by the Laisk method, ambient CO2 level (Ca) was increased step-wise from 50 μmol mol−1 up to a maximum of 150 μmol mol−1 in six steps while keeping Iinc at three levels depending on the species. The three light levels chosen for maize were higher than for the other species, following preliminary trials to obtain linear A–Ci relationships. For Iinc response curves as required by the Kok method and the new method, Iinc was in a serial 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 50, 70, 100, 150, and 200 μmol mol−1, while keeping Ca at 370 μmol mol−1 and O2 at 21% O2. For rice, potato, and maize, the light response of the same leaves was also measured at 2% O2. Leaf photosynthesis and respiration may acclimate to incident light conditions during measurement. To test whether the estimated Rd by the new method is affected by the direction of changing light levels, a second, separate set of measurements were undertaken for wheat, rice, and maize, in which both increasing and decreasing series of the above light levels were applied for each of the two O2 levels.

For the measurements at 2% O2, a gas cylinder containing a mixture of 2% O2 and 98% N2 was used. Gas from the cylinder was humidified and supplied to the Li-Cor 6400 where CO2 was blended with the gas. CO2 exchange data where the set Ca values were lower than the ambient air value (i.e. those measurements required for the Laisk method) were corrected for leakage of CO2 into the leaf cuvette, using measurements with heat-killed leaves (Flexas et al., 2007a).

The value of Rdk was measured 15–20 min after leaves had been placed in darkness. For measurements at each irradiance or CO2 step, A was allowed to reach steady state, after which Fs (the steady-state fluorescence) was recorded from the leaf, and then a saturating light pulse (>8500 μmol m−2 s−1 for 0.8 s) was applied to determine F'm (the maximum fluorescence during the saturating light pulse). The apparent PSII e– transport efficiency was calculated as: ΔF/F'm=(F'm–Fs)/F'm (Genty et al., 1989). This ΔF/F'm was treated in the present analysis as a true PSII e– transport efficiency Φ2, because the ratio ΔF/F'm:Φ2, if not equal to 1, has an impact on the value of parameter s but not on the estimated Rd (Yin et al., 2009).

Analysis methods

Regression was performed on the mean values of measurements across four replicated leaves. For all methods, data points at high ends that apparently deviated from the required linear pattern were dropped. For the Kok method and the new method, only data of the linear range at light levels above the Kok break point, if the Kok effect occurred significantly, were used to estimate Rd, by the simple linear regression procedure in MS-Excel. As actual values of irradiance may deviate slightly from the Iinc set values, the Iinc values incident on a leaf assessed by the in-chamber quantum sensor of Li-Cor 6400 were used for analysis. For the Laisk method, the three linear regression lines were forced to intersect at the same point to obtain a single estimate of Rd from each data set, although the lines might not have joined exactly at the same point if regression was carried out separately for the three light levels. Therefore, the PROC NLIN of SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used to fit data for the Laisk method. The SAS codes can be obtained upon request.

Results

Comparison of the estimates by the three methods

Data from the first set of measurements were analysed to compare Rd estimated by the three methods. The measured A–Ci curves at three light intensities for the five C3 species confirmed a general linear pattern with a common intersection as required by the Laisk method. An example of the curves is shown in Fig. 1a for wheat. This common intersection was found for all C3 species below the line A=0; therefore, the estimated Rd was positive for all these species. For the C4 species maize, however, the identified intersection point was well above the line A=0 (Fig. 1b), suggesting a negative Rd. C4 plants have a CO2-concentrating mechanism that allows a high CO2 concentration at Rubisco active sites in bundle sheath cells even if Ci is low, thereby requiring higher irradiances to obtain linear A–Ci relationships and yielding quite high values of A at low Ci commonly applied (Fig. 1b). Since the negative Rd is highly unlikely, the Laisk method cannot be applied to estimate Rd in leaves of C4 plants.

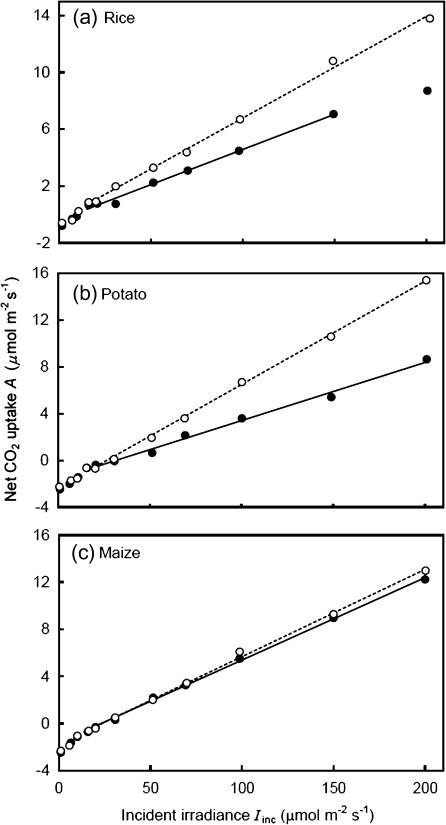

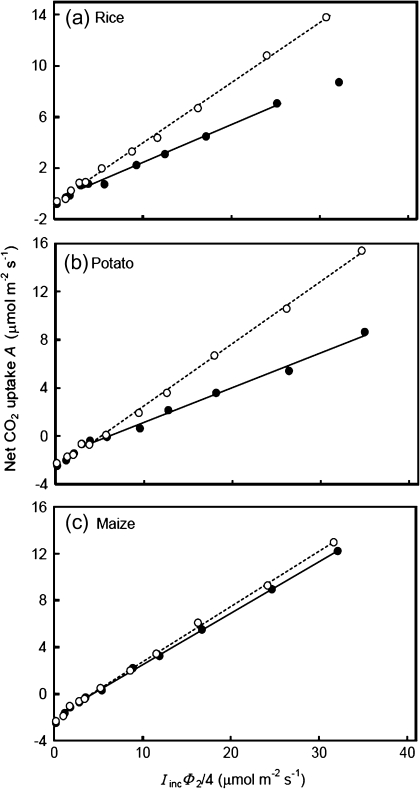

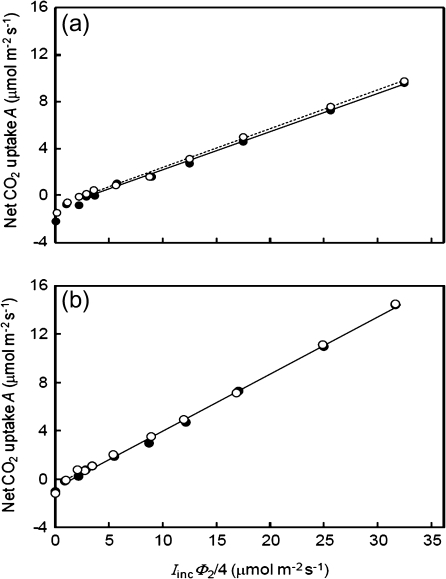

In contrast to the Laisk method, both the Kok method and the new CF method can be applied to estimate Rd of both C3 and C4 leaves, utilizing the linear part beyond the Kok break point of the A–Iinc and A–IincΦ2/4 relationships, respectively (Figs 2, 3). There were apparent deviations from linearity at the high end of the A–Iinc relationship in some plants, for example tomato (result not shown), and this deviation was only partially corrected when the A–IincΦ2/4 relationship was applied. These deviated points, therefore, were excluded in linear regression to estimate Rd for the two methods. At 21% O2, the slope of the A–Iinc relationships at the lower end when Iinc was around the light compensation point or lower was clearly higher, although for wheat and maize the change of the slope value was small, suggesting the occurrence of a significant Kok effect in most C3 species. Similar changes in the slope, albeit smaller, were also identified at 2% O2 and in maize. This abrupt change of the slope value was clearly shown in the A–IincΦ2/4 relationship as well (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Net CO2 assimilation rate (A) as a function of limiting incident irradiances (Iinc) at ambient air CO2 with 21% (filled circles) and 2% (open circles) O2 levels. Each data point represents the mean of measurements from four replicated plants. Solid and dotted lines represent regressions for data within the linear range from irradiance levels higher than the Kok break point at 21% and 2% O2, respectively. The extrapolation of these regression lines to the zero light level gives an estimation of -Rd, where Rd is the estimated respiration rate in the light (Kok method). The regression lines below the break point are not shown.

Fig. 3.

Net CO2 assimilation rate (A) as a function of the variable IincΦ2/4 (where Iinc is the incident irradiance and Φ2 is the quantum efficiency of PSII electron transport) at ambient air CO2 with 21% (filled circles) and 2% (open circles) O2 levels. Each data point represents the mean of measurements from four replicated plants. Solid and dotted lines represent regressions for data within the linear range from irradiance levels higher than the break point at 21% and 2% O2, respectively. The extrapolation of these regression lines to the zero IincΦ2/4 level gives an estimation of -Rd, where Rd is the estimated respiration rate in the light (new CF method). The regression lines below the break point are not shown.

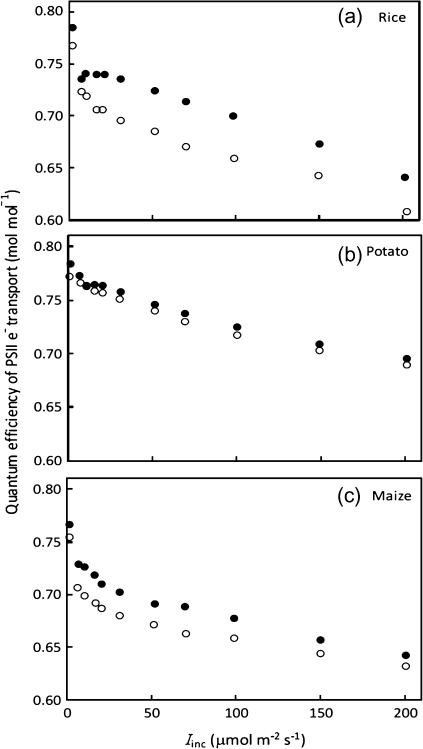

The Kok method requires a linear A–Iinc relationship beyond the Kok break point (Fig. 2). Such a linear relationship assumes that Φ2 is constant within the range of Iinc used. However, CF measurements showed that the apparent quantum efficiency of PSII e– transport (ΔF/F'm) decreased continuously with increasing Iinc, even within the limiting irradiance range (Fig. 4). The new CF method for Rd estimation accounts for such a decline of Φ2 by analysing the A–IincΦ2/4 relationships (Fig. 3). For this reason, the Rd values estimated by the CF method were consistently higher than those estimated by the Kok method (Table 1), on average, by 20%.

Fig. 4.

Quantum efficiency of PSII electron transport (as indicated by chlorophyll fluorescence data for the apparent PSII quantum efficiency ΔF/F'm) as a function of incident irradiance Iinc at ambient air CO2 with 21% (filled circles) and 2% (open circles) O2 levels for rice, potato, and maize. Each data point represents the mean of measurements from four replicated plants.

Table 1.

Value of the day respiration Rd (SE of the estimate in parentheses) estimated by three methods (i.e. Laisk, Kok, and CF), the intercept value at the A-axis by extrapolating the linear relationship below the break point (see Figs 2 and 3), and the mean value of the respiration rate in darkness Rdk across four replications (SE of the mean in parentheses), for leaves in six crop species

| Crop | O2 (%) |

Rd |

Intercept at A-axis |

Rdk | ||||

| Laisk | Kok | CF | Kok | CF | ||||

| C3 | Wheat | 21 | 0.972 (0.516) | 0.631 (0.151) | 1.043 (0.140) | 1.436 (0.129) | 1.474 (0.142) | 1.358 (0.048) |

| Rice | 21 | 0.628 (0.511) | 0.368 (0.146) | 0.522 (0.172) | 0.903 (0.218) | 0.901 (0.218) | 0.806 (0.122) | |

| 2 | – | 0.369 (0.155) | 0.744 (0.149) | 0.984 (0.327) | 1.015 (0.336) | 0.608 (0.120) | ||

| Potato | 21 | 1.522 (0.612) | 1.563 (0.209) | 1.751 (0.229) | 2.725 (0.218) | 2.735 (0.220) | 2.468 (0.150) | |

| 2 | – | 2.555 (0.105) | 2.890 (0.123) | 2.327 (0.384) | 2.339 (0.389) | 2.250 (0.263) | ||

| Tomato | 21 | 1.310 (0.729) | 0.962 (0.081) | 1.024 (0.084) | 1.790 (0.198) | 1.793 (0.201) | 1.675 (0.150) | |

| Rose | 21 | 1.320 (0.976) | 1.286 (0.069) | 1.503 (0.096) | 1.929 (0.340) | 1.938 (0.343) | 1.930 (0.188) | |

| C4 | Maize | 21 | NA | 1.614 (0.126) | 1.911 (0.084) | 2.213 (0.212) | 2.234 (0.209) | 2.473 (0.398) |

| 2 | NA | 1.740 (0.169) | 1.985 (0.133) | 2.417 (0.415) | 2.441 (0.418) | 2.325 (0.368) | ||

Data were from the first set of measurements. The unit of all parameters is μmol m−2 s−1.

NA, not applicable, as the Laisk method does not work for C4 species (see text); –, not measured, as the Laisk method is usually applied under the ambient O2 conditions.

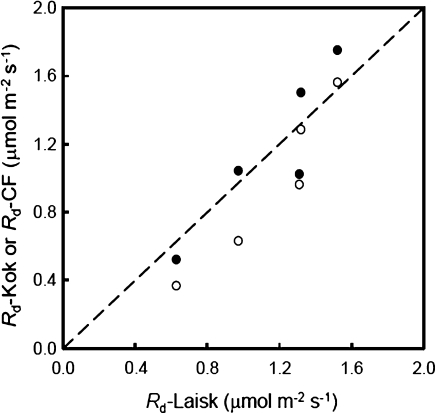

The values of Rd estimated by the Laisk method, which as usual was applied to ambient O2 condition (21%) for the measurements, varied from 0.63 μmol m−2 s−1 for rice to 1.52 μmol m−2 s−1 for potato (Table 1). For the common 21% O2, the overall trend for the variation of Rd among the C3 crops provided by the three methods was consistent. The difference in the Rd estimates may be due to differences in crop type and/or leaf ages. Generally, Rd estimated by the new CF method agreed well with those estimated by the Laisk method (Fig. 5). However, Rd estimated by the Kok method was mostly lower (Fig. 5) and, on average, was ∼87% of Rd obtained from the Laisk method.

Fig. 5.

Values of leaf respiration rate in the light (Rd) for five C3 species at 21% O2, estimated by the Kok method (open circles) or by the new CF method (filled circles), compared with the estimates for Rd by the Laisk method. The dashed line represents the 1:1 relationship.

Effect of the direction of changing irradiances on Rd estimated by the CF method

For a second set of measurements, the same levels of irradiances but two contrasting directions (increasing versus decreasing) of changing the irradiances were used for wheat, rice, and maize, to test whether the value of Rd estimated by the new CF method is sensitive to the direction of the change. An example of these measurements is given in Fig. 6 for wheat.

Fig. 6.

Net CO2 assimilation rate (A) of wheat leaves as a function of the variable IincΦ2/4 (where Iinc is the incident irradiance and Φ2 is the quantum efficiency of PSII electron transport) at ambient air CO2 with 21% (a) and 2% (b) O2 levels. Each data point represents the mean of measurements from four replicated plants. Solid and dotted lines represent regressions for data within the linear range from irradiance levels higher than the break point for increasing (filled circles) and decreasing (open circles) light series, respectively. The dotted regression line is invisible in (b) because it virtually overlaps with the solid line. The extrapolation of these regression lines to the zero IincΦ2/4 level gives an estimation of -Rd, where Rd is the estimated leaf respiration rate in the light (new CF method). The regression lines below the break point are not shown.

Using data points above the Kok break points, values of Rd estimated from measurements of increasing Iinc differed slightly from those estimated from measurements of decreasing Iinc (Table 2). In most cases, Rd values from increasing Iinc were slightly higher than those from decreasing Iinc, whereas in other cases the opposite was true. However, in no case was the difference statistically significant (P >0.10). Therefore, values of Rd estimated from the pooled data of the two changing series are also shown in Table 2. The differences in Rd among the three crops from this set of measurements agreed generally with those obtained from the first set of measurements (Table 1)—Rd,maize >Rd,wheat >Rd,rice.

Table 2.

Value of the day respiration Rd (SE of the estimate in parentheses) estimated by the CF method, and the mean value of the respiration rate in darkness Rdk across four replications (SE of the mean in parentheses), for leaves in three crop species

| Crop | O2 (%) |

Rd |

Rdk | |||

| Increasing | Decreasing | Pooled | ||||

| C3 | Wheat | 21 | 1.054 (0.113)a | 0.820 (0.112)a | 0.936 (0.083) | 1.782 (0.173) |

| 2 | 0.687 (0.093)a | 0.502 (0.093)a | 0.594 (0.068) | 1.076 (0.055) | ||

| Rice | 21 | 0.628 (0.190)a | 0.734 (0.188)a | 0.681 (0.130) | 0.975 (0.161) | |

| 2 | 0.552 (0.136)a | 0.402 (0.136)a | 0.477 (0.095) | 0.644 (0.061) | ||

| C4 | Maize | 21 | 2.629 (0.263)a | 2.086 (0.270)a | 2.365 (0.199) | 2.094 (0.273) |

| 2 | 1.284 (0.226)a | 1.928 (0.260)a | 1.562 (0.192) | 1.794 (0.202) | ||

Data were from the second set of measurements, where irradiances were changed in either increasing or decreasing order. The unit of Rd and Rdk is μmol m−2 s−1.

The same letter in a row means that the estimated Rd did not differ significantly (P >0.10) between increasing and decreasing irradiance series.

Effect of O2, and comparison between Rd and Rdk

For the Kok method and the new CF method, both 21% and 2% O2 levels were implemented for some crops; so for these crops, Rd was estimated by the methods for the two O2 levels (Tables 1, 2). For measurements at the 2% O2 level, a change of the slope for the Kok effect was relatively less apparent (Figs 2, 3, 6). As expected, 2% O2 (compared with 21% O2) suppressed photorespiration and thus increased the slope of the relationship above the Kok break point in the C3 crops wheat, rice, and potato, whereas the difference in the slope between the two O2 levels was very small in the C4 crop maize (Figs 2, 3). Below the Kok break point, there was no apparent difference between the two O2 levels in any species. As a result, the estimated Rd did not differ between the two O2 levels in the C4 species maize, but the CF method showed that it was higher at low than at high O2 levels for the C3 species rice and potato (Table 1). In contrast, from the second set of measurements, the estimated Rd was lower at low than at high O2 levels (Table 2), as the low O2 increased A somewhat already at very low irradiances (results not shown). However, this difference in Rd between the O2 levels was not significant in most cases, suggesting that the effect of O2 on Rd, if any, was not consistent.

Except for a few cases, the measured Rdk was higher than the Rd estimated by any of the three methods (Tables 1, 2). However, Rdk did not differ significantly (P >0.05) from the intercept at the A-axis by extrapolating the linear relationship below the Kok break point of the light response (Figs 2, 3, 6; Table 1).

Discussion

Comparison of the three methods

The Laisk (1977) method has been widely considered as a standard method to estimate leaf Rd indirectly in ecophysiological studies for C3 plants (e.g. Brooks and Farquhar, 1985; von Caemmerer et al., 1994; Peisker and Apel, 2001; Priault et al., 2006; Flexas et al., 2007b), probably also because it generates an estimate of another important parameter Ci*. Its applicability is confirmed by the present results (e.g. Fig. 1a) for five C3 species. However, the results for maize (Fig. 1b) suggest that the Laisk method yielded a negative Rd, which is physiologically impossible. Measurements show that there are no obvious differences in respiratory costs between C3 and C4 plants of similar habitats (Byrd et al., 1992). The present results are in line with the literature, in which the Laisk method has been used only for C3 plants. In fact, the theoretical basis of the Laisk method is Equation (1) or (2), which predicts that A has a common value (i.e. –Rd) at various light intensities when Cc=Γ* (equivalently when Ci=Ci*). So, strictly speaking, one must use Γ*, instead of Ci*, in the Laisk method, although few have done so because Γ* and Ci* differ by Rd/gm, and gm is difficult to measure (Harley et al., 1992; Flexas et al., 2007b; Yin and Struik, 2009). Since the CO2-concentrating mechanism plays such an important role in determining the C4 photosynthetic rate at low CO2 levels, the simple Equation (1) or (2), valid for C3 photosynthesis, does not suit for C4 photosynthesis. It is not surprising, therefore, that the Laisk method does not work for C4 plants.

Another disadvantage of the Laisk method is that the experiments must be performed at very low CO2 concentrations, far below normal ambient CO2 levels (Villar et al., 1994, 1995). When a large gradient exists between the set CO2 concentration and that in the ambient air, it is hard to avoid CO2 exchange or leakage between IRGA's leaf chamber of the open GE system and the surrounding air, leading to erroneous measurements of A and Ci (Flexas et al., 2007a). Therefore, a correction of A and Ci for this leakage is necessary (Flexas et al., 2007a; Rodeghiero et al., 2007). If no correction was made, the estimated Rd by the Laisk method would have become, on average, ∼50% higher than the values given in Table 1. The reported increase of leaf respiration with a short-term decrease in CO2 concentration (e.g. Villar et al., 1994; Atkin et al., 2000), seemingly explained by CO2 acting as an inhibitor of certain enzymes, means a further uncertainty in the estimated Rd by the Laisk method, although such an impact of CO2 on leaf respiration was not always evident (Brooks and Farquhar, 1985; Kirschbaum and Farquhar, 1987; Tjoelker et al., 2001). Amthor et al. (2001) suggested that earlier reported changes of leaf respiration with the CO2 level may have been due to small leaks in the GE measurement systems.

The above major disadvantages of the Laisk method can be overcome by the Kok method and the new CF method, which can be implemented under ambient CO2 conditions and are applicable to both C3 and C4 species. For example, the Kok method was used to assess the quantum yield of CO2 assimilation (ΦCO2) as well as Rd in a large number of C3, C4, and intermediate species (Björkman and Demmig, 1987). This is because the Kok and the CF methods use data measured under limiting irradiance, which is the predominant factor determining photosynthesis, so Equation (1) or (2) applies even for C4 photosynthesis. Furthermore, the present measurements showed that data in the low Ci portions of A–Ci curves required by the Laisk method generally had more noise (were more scattered) than those in the low portions of light response curves required by the Kok method and the new CF method, probably because the former involves use of additional data for transpiration (to calculate Ci), whose measurements are sensitive to uncontrolled environmental perturbations. This uncertainty is also reflected by the standard errors of Rd estimates which were higher for the Laisk method than for the other two methods (Table 1). In line with the results of Villar et al. (1994), the present values of Rd estimated by the Kok method were generally lower than those by the Laisk method (Fig. 5; Table 1). However, values estimated by the new CF method were in better agreement with those estimated by the Laisk method (Fig. 5; Table 1).

The difference between the Kok method and the new method is that not only data from GE measurements on A but also those from CF measurements on ΔF/F'm are used in the new method. According to Equation (3), the Kok method implicitly assumes that like coefficients β and ρ2, Φ2 does not vary with Iinc within the used data range. However, data from CF measurements reveal that the loss of Φ2, as indicated by ΔF/F'm, develops as the irradiance increases even within low light ranges (Fig. 4; see also Genty and Harbinson, 1996), implying a non-linear A–Iinc relationship. Thus, the new method using the information of CF (in addition to GE information) corrects the error of the Kok method of the constant Φ2 over low irradiances, thereby accounting for any pitfall caused by possible non-linearity, undetectable by visual or statistical inspection (Fig. 2), between A and Iinc of the used data range (Yin et al., 2009). Use of the combined GE and CF data in the new method is justified by a generally observed linear relationship between ΔF/F'm and ΦCO2 over a wide range of conditions for C3 (e.g. Genty et al., 1989) and C4 (Edwards and Baker, 1993) species. The sometimes reported break of the linearity between ΔF/F'm and ΦCO2 at low light levels (e.g. Seaton and Walker, 1990) may be, at least partly, due to uncertainty in estimating Rd (Edwards and Baker, 1993) since Rd accounts for a large portion of the variation in ΦCO2 under low light conditions. It is worth noting that data for the new method have to be obtained from a small (e.g. 2 cm2) leaf chamber because errors with CF measurements for ΔF/F'm are inversely proportional to leaf area, although this limitation does not apply for fluorescence systems based on area-imaging cameras rather than spot measurements. However, the Kok method, like the Laisk method, uses only GE data; therefore, data would be collected with the large chamber (e.g. 6 cm2) to reduce the noise-to-signal ratio and to represent the whole leaf better.

In short, each method has its own advantages and disadvantages, which are summarized in Table 3. It would be useful to compare the results of these indirect methods with those obtained by one of the methods that directly measure Rd (e.g. those of Haupt-Herting et al., 2001; Loreto et al., 2001; Pärnik and Keerberg, 2007).

Table 3.

Evaluation of the three methods to estimate leaf respiration rate in the light Rd

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

| The Laisk method | 1. Data used could be obtained from a large (e.g. 6 cm2) leaf chamber. | 1. Low Ci levels have to be used, which are far from the level for normal plant growth. |

| 2. The method provides additional estimates on carboxylation efficiencies at various irradiances and on the very useful parameter Ci*. | 2. It is required to correct for the CO2 leakage during the gas exchange measurement. | |

| 3. The method could be used to check roughly if Rd varies with irradiance levels. | 3. The method is applicable only for C3, not for C4 plants. | |

| 4. The method is sensitive to errors of the system in measuring transpiration that affects Ci. | ||

| The Kok method | 1. Data used could be obtained from a large (e.g. 6 cm2) leaf chamber. | 1. The method is based on the assumption that Φ2 is constant within used irradiances, which is highly unlikely; as a result, it may underestimate Rd. |

| 2. The method is applicable for both C3 and C4 plants. | 2. Low irradiance levels have to be used, which may not represent the light level for normal plant growth | |

| 3. The method could potentially be applied to the CO2 levels for normal plant growth; so it is possible that no correction for CO2 leakage during measurement is required. | 3. Theoretically, the method works best for the non-photorespiratory condition. | |

| 4. The method provides additional estimate for ΦCO2. | ||

| 5. The method is insensitive to errors in measuring transpiration. | ||

| 6. The method could be used to check if Rd varies with CO2 levels. | ||

| The new CF method | 1. Using CF information, the method corrects for the error of the Kok method assuming a constant Φ2 with low irradiances; as a result, data of a wider range of irradiance could be useable, relative to the Kok method. | 1. Data used have to be obtained from a small (e.g. 2 cm2) leaf chamber because errors with CF measurements are inversely proportional to leaf area (but note that this limitation does not apply for fluorescence systems based on area-imaging cameras). |

| 2. The method is applicable for both C3 and C4 plants. | 2. Generally low irradiance levels are used, which may not represent the light level for normal plant growth. | |

| 3. The method could potentially be applied to the CO2 levels for normal plant growth; so it is possible that no correction for CO2 leakage during measurement is required. | 3. Theoretically, the method works best for the non-photorespiratory condition. | |

| 4. The method provides additional estimate for parameter s, that lumps a number of useful physiological parameters (see text). | ||

| 5. The method is insensitive to errors in measuring transpiration. | ||

| 6. The method could be used to check if Rd varies with CO2 levels. |

Little evidence for dependence of Rd on the direction of changing irradiance

One relevant issue for using the new method is whether or not the direction of changing irradiances has an impact on the estimated Rd, since the CF method, like the Kok method, requires a series of data points across the low light range. As discussed in the section ‘Theoretical considerations’, both methods are theoretically valid under non-photorespiratory conditions (Table 3). For normal photorespiratory conditions, the methods rely on the assumption that variation of Cc, and therefore Ci, with irradiance is negligible. This assumption is questionable given that at a given Ca, the variation of Ci with irradiance is most apparent in the low Iinc range, within which data are collected to estimate Rd by the Kok and CF methods. High irradiances induce stomatal opening, which may have a consequence on GE and Ci at subsequent light levels and, therefore, on the estimated Rd, especially under photorespiratory condition. For this reason, the second set of measurements were conducted using the same light levels but contrasting (increasing versus decreasing) directions of changing irradiances.

The estimated Rd values by the CF method from measurements of increasing and decreasing irradiances were not identical (Table 2). However, the difference was not significant, nor was it consistent or systematic. As discussed above, the effect of the direction of changing irradiance on Rd, if any, is expected to occur under photorespiratory conditions. However, any difference in Rd between the two light series was not higher at 21% than at 2% O2 levels in two C3 crops, and not higher in C3 than in C4 species (Table 2). Moreover, a ‘drifting’ in the actual values of Rd may occur with increasing or decreasing light since it is hard to complete low-light series measurements quickly enough to preclude the drifting. Therefore, it is believed that the difference in the estimated Rd between the light series was possibly due to measurement noise or ‘drifting’, rather than to biological mechanisms.

Effect of light on mitochondrial respiration, and the Kok effect

Values of Rd estimated by all three methods were generally lower than those of Rdk (Tables 1, 2), supporting the assertion that leaf respiration can be inhibited by light (Sharp et al., 1984; Brooks and Farquhar, 1985; Villar et al., 1994, 1995; Laisk and Loreto, 1996; Atkin et al., 1997, 2000; Wang et al., 2001; Shapiro et al., 2004). An in vivo metabolic study (Tcherkez et al., 2005) indicated that the main inhibited steps were the entrance of hexose molecules into the glycolytic pathway and the Krebs cycle. However, whether this difference between Rd and Rdk is due to real inhibition has been challenged (e.g. Loreto et al., 2001) because CO2 released from respiration during illumination is possibly re-fixed by photosynthesis.

Another uncertainty is the assumption used in all three methods (Laisk, Kok, and CF) that Rd is independent of light intensity, and the assumption seems to be supported by some experimental studies (e.g. Haupt-Herting et al., 2001). Furthermore, both Kok and CF methods implicitly assume that Rd is maximally inhibited by light at the Kok break point. However, it has been shown that the extent to which irradiance inhibits Rd increases with increasing light intensity (Brooks and Farquhar, 1985; Villar et al., 1994, 1995; Laisk and Loreto, 1996; Atkin et al., 2000), well beyond the break point. It has been suggested that the Kok effect is caused by the progressive, light-induced inhibition of leaf respiration (e.g. Sharp et al., 1984; Ribas-Carbo, 2010), which is also in line with the present results that Rdk did not differ from the intercept of the line below the Kok break point (Table 1). Previously, the Kok effect was suggested to be associated with photorespiration given the observed absence of the Kok effect under low O2 conditions or in C4 species that suppress photorespiration (e.g. Ishii and Murata, 1978). The observation that the Kok effect is present under high CO2 but absent under low O2 (Sharp et al., 1984) means that a possible decrease in the ratio of photorespiration to photosynthesis with decreasing irradiance has little relevance to the Kok effect. The present data also showed that the Kok effect occurred at 2% O2 or in C4, albeit to a lesser extent compared with 21% O2 or C3 crops (Fig. 2), and that the Kok effect did not disappear when values of A were plotted against IincΦ2/4 (Fig. 3). A new analytical model hypothesizing that the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway is progressively inhibited by the light-driven increase in thylakoid reducing power can reproduce the abrupt transition point of the Kok effect (Buckley and Adams, 2011). Direct measurements of Rd (with procedures from, for example, Haupt-Herting et al., 2001; Loreto et al., 2001; Pinelli and Loreto, 2003; Pärnik and Keerberg, 2007), combined with a model analysis, might help to understand fully the inter-entangling of the Kok effect, light inhibition of Rd, and photorespiration, and to verify the estimates of Rd by the indirect methods evaluated in this study.

Acknowledgments

The stay of ZS in Wageningen was funded by the China Scholarship Council. We thank Dr W. van Ieperen for his support with the measurements, and Mr P. E. L. van der Putten for managing the plants in the glasshouse. This work was carried out within the research programme ‘BioSolar Cells’.

References

- Amthor JS, Koch GW, Willms JR, Layzell DB. Leaf O2 uptake in the dark is independent of coincident CO2 partial pressure. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2001;52:2235–2238. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.364.2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin OK, Evans JR, Ball MC, Lambers H, Pons TL. Leaf respiration of snow gum in the light and dark. Interactions between temperature and irradiance. Plant Physiology. 2000;122:915–923. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.3.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin OK, Westbeek MHM, Cambridge ML, Lambers H, Pons TL. Leaf respiration in light and darkness—a comparison of slow- and fast-growing Poa species. Plant Physiology. 1997;113:961–965. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.3.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azcón-Bieto J, Farquhar GD, Caballero A. Effects of temperature, oxygen concentration, leaf age and seasonal variation on the CO2 compensation point of Lolium perenne L. Comparison with a mathematical model including non-photorespiratory CO2 production in the light. Planta. 1981;152:497–504. doi: 10.1007/BF00380820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björkman O, Demmig B. Photon yield of O2 evolution and chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics at 77 K among vascular plants of diverse origins. Planta. 1987;170:489–504. doi: 10.1007/BF00402983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks A, Farquhar GD. Effect of temperature on the CO2/O2 specificity of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and the rate of respiration in the light. Planta. 1985;165:397–406. doi: 10.1007/BF00392238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley TN, Adams MA. An analytical model of non-photorespiratory CO2 release in the light and dark in leaves of C3 species based on stoichiometric flux balance. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2011;34:89–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd GT, Sage RF, Brown RH. A comparison of dark respiration between C3 and C4 plants. Plant Physiology. 1992;100:191–198. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.1.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards GE, Baker NR. Can assimilation in maize leaves be predicted accurately from chlorophyll fluorescence analysis? Photosynthesis Research. 1993;37:89–102. doi: 10.1007/BF02187468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA. A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta. 1980;149:78–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00386231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Diaz-Espejo A, Berry JA, Cifre J, Galmes J, Kaldenhoff R, Medrano H, Ribas-Carbó M. Analysis of leakage in IRGA's leaf chambers of open gas exchange systems: quantification and its effects in photosynthesis parameterization. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2007a;58:1533–1543. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Ortuño MF, Ribas-Carbo M, Diaz-Espejo A, Flórez-Sarasa ID, Medrano H. Mesophyll conductance to CO2 in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytologist. 2007b;175:501–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genty B, Briantais J, Baker N. The relationship between the quantum yield of photosynthetic electron transport and quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1989;990:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Genty B, Harbinson J. Regulation of light utilization for photosynthetic electron transport. In: Baker NR, editor. Photosynthesis and the environment. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996. pp. 67–99. [Google Scholar]

- Harley PC, Loreto F, Di Marco G, Sharkey TD. Theoretical considerations when estimating the mesophyll conductance to CO2 flux by analysis of the response of photosynthesis to CO2. Plant Physiology. 1992;98:1429–1436. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.4.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt-Herting S, Klug K, Fock HP. A new approach to measure gross CO2 fluxes in leaves. Gross CO2 assimilation, photorespiration, and mitochondrial respiration in the light in tomato under drought stress. Plant Physiology. 2001;126:388–396. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.1.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii R, Murata Y. Further evidence of the Kok effect in C3 plants and the effects of environmental factors on it. Japanese Journal of Crop Science. 1978;47:547–550. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum MUF, Farquhar GD. Investigation of the CO2 dependence of quantum yield and respiration in Eucalyptus pauciflora. Plant Physiology. 1987;83:1032–1036. doi: 10.1104/pp.83.4.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok B. A critical consideration of the quantum yield of Chlorella-photosynthesis. Enzymologia. 1948;13:1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Laisk AK. Kinetics of photosynthesis and photorespiration in C3 plants. Nauka Moscow (in Russian) 1977 [Google Scholar]

- Laisk A, Loreto F. Determining photosynthetic parameters from leaf CO2 exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence. Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase specificity factor, dark respiration in the light, excitation distribution between photosystems, alternative electron transport rate, and mesophyll diffusion resistance. Plant Physiology. 1996;110:903–912. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.3.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreto F, Velikova V, Di Marco G. Respiration in the light measured by 12CO2 emission in 13CO2 atmosphere in maize leaves. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology. 2001;28:1103–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Miyake C, Yokota A. Physiological functions of the water–water cycle (Mehler reactions) and the cyclic electron flow around PSI in rice leaves. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2002;43:1017–1026. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pärnik T, Keerberg O. Advanced radiogasometric method for the determination of the rates of photorespiratory and respiratory decarboxylations of primary and stored photosynthates under steady-state photosynthesis. Physiologia Plantarum. 2007;129:33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Peisker M, Apel H. Inhibition by light of CO2 evolution from dark respiration: comparison of two gas exchange methods. Photosynthesis Research. 2001;70:291–298. doi: 10.1023/A:1014799118368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RB. Partitioning of noncyclic photosynthetic electron transport to O2-dependent dissipative processes as probed by fluorescence and CO2 exchange. Plant Physiology. 1989;90:1322–1328. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.4.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinelli P, Loreto F. 12CO2 emission from different metabolic pathways measured in illustrated and darkened C3 and C4 leaves at low, atmospheric and elevated CO2 concentration. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2003;54:1761–1769. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priault P, Tckerkez G, Cornic G, De Paepe R, Naik R, Ghashghaine J, Streb P. The lack of mitochondrial complex I in a CMSII mutant of Nicotiana sylvestris increases photorespiration through an increased internal resistance to CO2 diffusion. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2006;57:3195–3207. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribas-Carbo M, Flexas J, Robinson SA, Tcherkez GGB. 2010 Essay 11.9: In vivo measurement of plant respiration. Plant Physiology Online at: http://5e.plantphys.net/article.php?ch=eandid=480. [Google Scholar]

- Rodeghiero M, Niinemets Ü, Cescatti A. Major diffusion leaks of clamp-on leaf cuvettes still unaccounted: how erroneous are the estimates of Farquhar et al., model parameters? Plant, Cell and Environment. 2007;30:1006–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.001689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton GGR, Walker DA. Chlorophyll fluorescence as a measure of photosynthetic carbon assimilation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 1990;242:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro JB, Griffin KL, Lewis JD, Tissue DT. Response of Xanthium strumarium leaf respiration in the light to elevated CO2 concentration, nitrogen availability and temperature. New Phytologist. 2004;162:377–386. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp RE, Matthews MA, Boyer JS. Kok effect and the quantum yield of photosynthesis. Light partially inhibits dark respiration. Plant Physiology. 1984;75:95–101. doi: 10.1104/pp.75.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tcherkez G, Cornic G, Bligny R, Gout E, Ghashghaie J. In vivo respiratory metabolism of illuminated leaves. Plant Physiology. 2005;138:1596–1606. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.062141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjoelker MG, Oleksyn J, Lee TD, Reich PB. Direct inhibition of leaf dark respiration by elevated CO2 is minor in 12 grassland species. New Phytologist. 2001;150:419–424. [Google Scholar]

- Villar R, Held AA, Merino J. Comparison of methods to estimate dark respiration in the light of leaves of two woody species. Plant Physiology. 1994;105:167–172. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.1.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar R, Held AA, Merino J. Dark leaf respiration in light and darkness of an evergreen and a deciduous plant species. Plant Physiology. 1995;107:421–427. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.2.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Evans JR, Hudson GS, Andrews TJ. The kinetics of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase in vivo inferred from measurements of photosynthesis in leaves of transgenic tobacco. Planta. 1994;195:88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Lewis JD, Tissue DT, Seemann JR, Griffin KL. Effects of elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration on leaf dark respiration of Xanthium strumarium in light and in darkness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2001;98:2479–2484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051622998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Harbinson J, Struik PC. Mathematical review of literature to assess alternative electron transports and interphotosystem excitation partitioning of steady-state C3 photosynthesis under limiting light. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2006;29:1771–1782. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01554.x. (with a corrigendum in 29, 2252) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Struik PC. Theoretical reconsiderations when estimating the mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion in leaves of C3 plants by analysis of combined gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence measurements. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2009;32:1513–1524. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02016.x. (with a corrigendum in 33, 1595) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Struik PC, Romero P, Harbinson J, Evers JB, van der Putten PEL, Vos J. Using combined measurements of gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence to estimate parameters of a biochemical C3 photosynthesis model: a critical appraisal and a new integrated approach applied to leaves in a wheat (Triticum aestivum) canopy. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2009;32:448–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, van Oijen M, Schapendonk AHCM. Extension of a biochemical model for the generalized stoichiometry of electron transport limited C3 photosynthesis. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2004;27:1211–1222. [Google Scholar]