Abstract

Oxidative stress has been broadly implicated as a cause of cell death and neural degeneration in multiple disease conditions; however, the evidence for successful intervention with dietary antioxidant manipulations has been mixed. In this study, we investigated the potential for protection of cells in the inner ear using a dietary supplement with multiple antioxidant components, selected for their potential interactive effectiveness. Protection against permanent threshold shift (PTS) was observed in CBA/J mice maintained on a diet supplemented with a combination of β-carotene, vitamins C and E, and magnesium when compared to PTS in control mice maintained on a nutritionally complete control diet. Although hair cell survival was not enhanced, noise-induced loss of Type II fibrocytes in the lateral wall was significantly reduced (p<0.05), and there was a trend towards less noise-induced loss in strial cell density in animals maintained on the supplemented diet. Taken together, our data suggest that pre-noise oral treatment with the high-nutrient diet can protect cells in the inner ear and reduce PTS in mice. Demonstration of functional and morphological preservation of cells in the inner ear with oral administration of this antioxidant supplemented diet supports the possibility of translation to human patients, and suggests an opportunity to evaluate antioxidant protection in mouse models of oxidative stress-related disease and pathology.

Keywords: oxidative stress, antioxidant, free radical, scavenger, beta-carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, magnesium, noise, hearing

Introduction

Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress have been broadly implicated in multiple progressive neurodegenerative disease, and treatment with free radical scavengers to reduce disease progression has been suggested for the two most frequent human neurodegenerative diseases, which include Alzheimer’s disease (1–4) and Parkinson’s disease (5–10). Indeed, Huntington’s disease, Friedrich’s ataxia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, epilepsy, and even acute injury (such as spinal cord injury) are all considered to be driven by cytosolic oxidative stress, and antioxidant therapies are of broad interest (11, 12).

Free radical insult also drives cell injury and cell death in the inner ear that is associated with hearing loss. Free radicals are produced after noise exposure, drug or other chemical insults, and perhaps even during aging (for reviews, see 13, 14, 15). Thus, there exists a compelling rationale for investigations into the use of antioxidant agents to reduce permanent noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL), also termed permanent threshold shift (PTS). Noise exposure specifically induces free radical production in supporting cells, outer hair cells, and cells in the lateral wall, and both reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) are produced (13, 16–18). Several endogenous antioxidant precursors and endogenous antioxidant mimetics have proven effective in reducing PTS in animal models (such as ebselen, D-methionine and N-acetylcysteine, see 19, 20–23). Although these agents clearly reduced PTS, the protection achieved to date using single-agent therapeutic approaches to reduce PTS has, in general, appeared incomplete (for recent review, see 24). This likely reflects the fact that noise injury involves a number of injury pathways, of which oxidative stress is only one. Even within the category of oxidative stress, there are multiple varieties of ROS, generated in different cellular compartments. Based on their activity, location, and lipid solubility, different ROS are more readily remediated by different types of antioxidants.

In an effort to close the ‘efficacy gap’ obtained using single-agent approaches, a number of investigations have explored combinations of agents (25–29). Indeed, because they target a wider variety of free radicals and operate in various cell compartments, treatments that combine multiple antioxidants have been proposed as treatment options for multiple disease conditions (for examples and reviews, see 30, 31–38). Vitamins A, C, and E have been a particularly well-investigated combination as together they act to scavenge singlet oxygen, reduce peroxyl radicals, and arrest or prevent lipid peroxidation, in mitochondria, nuclei, endoplasmic reticulum, and lipid membranes (for examples and reviews, see 32, 39, 40–49).

Treatment with the combination of antioxidants β-carotene (which is metabolized to form vitamin A), vitamin C, and vitamin E, as well as magnesium, reduced NIHL and hair cell death in guinea pigs exposed to loud noise (26). Magnesium was included in the combination used in that study based on its known vasodilating properties (see 50, 51–60). Noise exposure reduces blood vessel diameter and red blood cell velocity and decreases blood flow to the cochlea (61–67). Vasodilating agents should not only serve to promote blood flow in the inner ear during noise stress, but should also provide for greater quantities of the blood-borne antioxidants to perfuse the inner ear tissues. Magnesium also modulates calcium channel permeability, influx of calcium into cochlear hair cells, and glutamate release (68, 69). Both increased activity at glutamate receptors (either after noise or during infusion of glutamate receptor agonists) and deficits in calcium homeostasis have been linked to hearing loss (for reviews see 14, 70, 71). Finally, of particular interest, magnesium is increasingly considered to play a direct role in mediating both oxidative stress and DNA repair (72–75). While the protective effects of magnesium supplements may ultimately be related to some combination of these properties, magnesium clearly acted in synergy with antioxidants to attenuate PTS in the guinea pig (26). Reduction in PTS was robust in animals treated with the combination of β-carotene, vitamins C and E, and magnesium, and the nutrient combination was suggested as potentially useful for human patients based on extensive safety data, relatively low cost of dietary supplements, and widespread availability of dietary supplements.

Successful translation to human patients requires that the agents be delivered orally, without significantly compromising efficacy. Moving from injected treatments to an oral delivery paradigm has significantly compromised the efficacy of some other antioxidants. For example, protection is significantly reduced when N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is delivered via oral gavage instead of via injections (76). Treatment efficacy also has the potential to be modified with manipulation of the nutrient source. For example, we have replaced the water-soluble vitamin E analogue Trolox used in a previous study (see 26) with dietary α-tocopherol. In vitro antioxidant efficiency clearly varies across different forms of vitamin E (for review see 49). To explore the potential for therapeutic benefit with oral nutrient treatments, this study examined the protective effects of β-carotene, vitamins C and E, and magnesium using CBA/J mice maintained on various supplemented diets.

This study extends earlier findings in several important ways. First, this work expands previous studies from the guinea pig to the mouse, confirming protection of the inner ear with antioxidant nutrients in a second rodent model. Second, in the current investigation, all agents were delivered orally via modified diets. Confirmation of an oral treatment that effectively reduces oxidative stress, and can be easily delivered as part of the daily diet, will be useful in other pre-clinical studies designed to evaluate the potential for antioxidant benefits across disease models given the contributions of oxidative stress to multiple disease conditions. Demonstration of an “effective” antioxidant diet in mice is particularly useful, as this also allows the future possibility of mechanistic studies on the interaction of genes and diet. Third, treatments were initiated 28 days pre-noise to allow plasma and tissue levels to stabilize. Previous studies have shown that stable plasma and tissue levels of vitamin C are obtained (in humans) approximately 3 weeks after beginning dietary treatment (77), and vitamin E levels similarly stabilize over an initial month-long treatment window (for review, see 78).

Materials and Methods

Subjects

A total of 31 5–6 month old male CBA/J mice were included as subjects. The choice of strain was based on the common application of CBA/Js as ‘good hearing’ mice (79) and the age range was selected to assure that all subjects were outside the age range during which vulnerability is increased (80). Selection of male subjects was based on possible gender-based differences in ROS detoxification (81), activity of glutathione S-transferase in the cochlea (82), and variation in susceptibility to NIHL (83). Mice were either purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine), or were offspring of mice purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. All mice were maintained on Control Diet for at least one-month prior to dietary manipulation; control mice were maintained on Control Diet for an additional 28 days while experimental subjects began dietary treatments 28 days pre-noise. All subjects demonstrated normal pre-noise (baseline) auditory brainstem response (ABR) thresholds at 5, 10, 20, 28.3, and 40 kHz. Effects of noise were measured using repeat ABR tests14–16 days after a single noise exposure; after ABR measurements the tissues were harvested for histology. The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the University Committee for the Care and Use of Animals (UCUCA) at Washington University in St. Louis, and all procedures conformed to the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Detailed descriptions of dietary manipulation, ABR test procedures, noise exposures, and tissue processing are provided below.

Dietary Manipulation

Custom diets were formulated with input from a Harlan-Teklad nutritionist, and were based on a nutritionally complete base diet recommended by the American Institute of Nutrition (AIN-93M, for maintenance of mature rodents). During formulation of all AIN-93M diets (including Control Diet), regular soybean oil was replaced with tocopherol-stripped oil and regular casein was replaced with alcohol-extracted casein to minimize uncontrolled sources of vitamin E. All diets (control and supplemented) contained standard vitamin (10 mg additive per kg chow, AIN-93-VX, vitamin mix TD.94047) and mineral (35 mg additive per kg chow, AIN-93-MX, mineral mix TD.94049) additives. The Control Diet did not provide ascorbic acid. Mice, like most mammals, produce endogenous vitamin C (84, 85); thus, normal laboratory diets for mice do not include vitamin C.

All mice were maintained on Control Diet for at least one month prior to dietary manipulation; of these, 16 control mice were maintained on Control Diet throughout the study. For the other remaining (experimental) subjects, dietary treatments began 28 days pre-noise, and continued for the remainder of the study. These subjects received diets with enhanced β-carotene (Sigma-Aldrich, #C9750), vitamin C (Rovimix Stay-C 35 from DSM, #0483044), vitamin E (Dry Vitamin E Acetate 50% Type SD from DSM, #0488550), and magnesium (magnesium citrate, anhydrous, USP from Spectrum Chemical, #M2036) (TD.07215/Diet A: n=8; TD.07506/Diet B: n=7; see Table 1). Diet B contained 2.9X β-carotene, 3.1X vitamin E, 1.6X vitamin C, and 1.7X magnesium in comparison to Diet A, while protein, fat, and caloric content did not vary across diets (see Table 1). Mice on the Control diet were matched to mice on the Experimental Diets with respect to study entry and noise exposure sessions.

Table 1.

Custom diet formulations. All amounts are mg additive per kg of pelleted chow.

| TD.07213 “Control” | TD.07215 “Diet A” | TD. 07506 “Diet B” | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium1 (mg/kg chow) | 500 | 2656 | 4500 |

| Beta-carotene2 (mg/kg chow) | 14 | 77 | 224 |

| Ascorbic acid3 (mg/kg chow) | 0 | 2250 | 3600 |

| Alpha-tocopherol3 (mg/kg chow) | 50 | 863 | 2650 |

| Vitamin Mix, AIN-93-VX (g/kg chow) | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Mineral Mix, AIN-93G-MX (g/kg chow) | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Corn starch (g/kg chow) | 465 | 443 | 377 |

| Maltodextrin (g/kg chow) | 155 | 155 | 100 |

| Sucrose (g/kg chow) | 100 | 100 | 200 |

| Protein (% by weight) | 12.8 | 12.8 | 12.8 |

| Carbohydrate (% by weight) | 68.4 | 66.3 | 65.2 |

| Fat (% by weight) | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Kcal/g | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

Quantity listed in control chow is derived from Mineral Mix AIN93G-MX, and quantities listed in Diet A and Diet B are a combination of Mineral Mix AIN93G-MX and added Magnesium.

Quantity of vitamin A in control mix is listed as the equivalent quantity of beta-carotene using the RAE conversion factor of 1 mg retinol =12 mg carotinoid. Quantity listed in control chow is derived from Vitamin Mix AIN93-VX and quantities listed in Diet A and Diet B are a combination of Vitamin Mix AIN93-VX and added beta-carotene.

Quantity listed in control chow is derived from Vitamin Mix AIN93-VX and quantities listed in Diet A and Diet B are a combination of Vitamin Mix AIN93-VX and added vitamins.

Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR)

Hearing assessment was performed in a foam-lined, single-walled soundproof room (IAC). Animals were anesthetized (80 mg/kg ketamine, 15 mg/kg xylazine, IP) and positioned dorsally in a custom head holder. Core temperature was maintained at 37.5 ± 1.0 °C using a DC electric heating pad in conjunction with a rectal probe (FHC). Platinum needle electrodes (Grass) were inserted subcutaneously just behind the right ear (active), at the vertex (reference), and in the back (ground). Electrodes were connected to a Grass P15 differential amplifier (100–10,000 Hz, ×100), then to a custom amplifier providing another 1,000X gain, then digitized at 30 kHz and visualized using Tucker Davis Technologies (TDT) System 2 hardware and software. Sine wave stimuli having 0.5 ms cos2 rise/fall times and 5.0 ms total duration were also generated and calibrated using TDT System2 hardware and software. Stimuli were presented free-field using TDT ES-1 speakers placed 7.0 cm from the right pinna and calibrated offline using an ACO Pacific 7016 ¼ inch microphone placed where the external auditory meatus would normally be. During ABR tests, tone burst stimuli at each frequency and level were presented up to 1,000 times at 20/sec. The minimum sound pressure level (SPL) required for visual detection of ABR Wave I was determined at 5, 10, 20, 28.3, and 40 kHz, using a 5 decibel (dB) minimum step size. Starting levels were typically 80 dB SPL, with level decreased in 10 dB steps until the response disappeared and then increased in 5 dB steps until responses reappeared.

Noise Exposure

The noise insult was an 8–16 kHz octave band noise (OBN) presented for 2 hrs; noise levels at various points in the exposure cage, measured using a B&K 4135 ¼ inch microphone in combination with a B&K 2231 sound level meter, ranged from 113–115 dB SPL. Noise exposures were performed in a single-walled soundproof room (IAC). The noise exposure apparatus consisted of a 21 × 21 × 11 cm wire cage mounted on a pedestal inserted into a B&K 3921 turntable. To ensure a uniform sound field, the cage was rotated at 1 revolution/80 s within a 42 × 42 cm metal frame. Motorola KSN1020A piezo ceramic speakers (four total) were attached to each side of the frame. Opposing speakers were oriented non-concentrically, parallel to the cage, and driven by separate channels of a Crown D150A power amplifier. Octave band noise was generated by General Radio 1310 generators and band-passed at 8–16 kHz by Krohn-Hite 3550 filters. All mice were exposed in pairs.

Tissue processing for histology

After final ABR recording, animals were overdosed with sodium pentobarbitol (4X surgical dose, 240 mg/kg) and perfused transcardially with cold 2.0% paraformaldehyde/2.0% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Each cochlea was rapidly isolated, immersed in the same fixative, and the stapes was immediately removed. After decalcification in sodium EDTA for 72 hours, cochleas were post-fixed in buffered 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in an ascending acetone series, and embedded in Epon.

Morphometric analysis

Embedded left and right cochleae were used for different analyses. Left cochleae were sectioned at 4 μm in the mid-modiolar plane for analysis of neurons and cells of the stria vascularis, spiral ligament, and spiral limbus. For each animal, 10 sections distributed evenly throughout the 200 μm sectioned distance were analyzed using bright field viewing with a Nikon Optiphot™ light microscope with a 100x oil objective and a calibrated grid ocular. Estimates of neuronal density were obtained in the lower basal turn, upper basal turn, and lower apical turn. Strial and ligament measures focused on the upper basal turn given that the type and extent of noise injury has been well characterized for this region after single exposures like those applied here (86). Lateral wall measures were based on previous studies of noise-related changes in stria vascularis and spiral ligament (86, 87), and included strial thickness, marginal cell density, intermediate cell density, basal cell density, strial capillary density, ligament thickness, and density in the ligament of Type I, II, and IV fibrocytes.

Stria vascularis

Strial thickness was measured orthogonal to the strial midpoint, as viewed in radial section. Marginal cells, intermediate cells, and basal cells were counted in an 80 μm linear segment of stria, centered at the midpoint. Only nucleated profiles were included. Unconnected capillary profiles were counted over the same 80 μm span. For each capillary profile, the diameter and basement membrane thickness were recorded.

Spiral ligament

Ligament thickness was measured on an axis co-linear with the strial midpoint. Type I, II, and IV fibrocytes were counted in a 1,600 μm2 area. These were identified based on location, an approach taken in previous studies (88–90). Only nucleated profiles were included.

Hair cell counts

For hair cell counts, embedded right cochleae were cut into quarter-turn segments, immersed in mineral oil in a depression slide, and viewed as surface preparations under Nomarski optics. Inner and outer hair cell densities were rendered as percent hair cells missing over the entire cochlea.

Results

Threshold protection with dietary antioxidant supplement

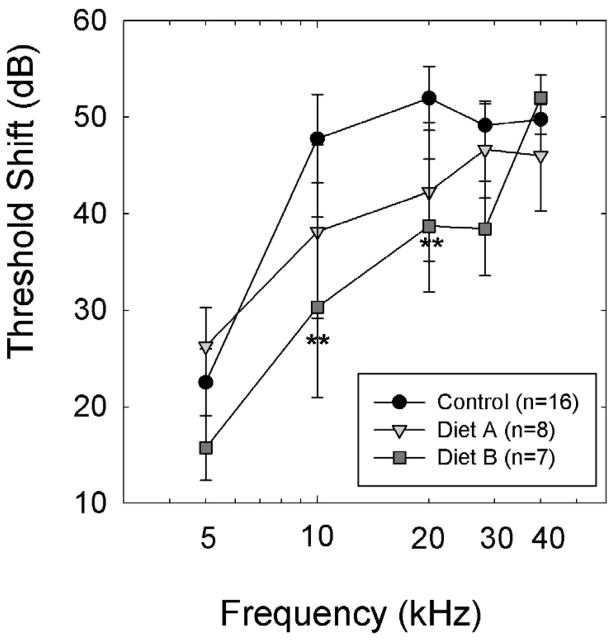

The Diet B nutrient combination reduced PTS relative to Control Diet (see Figure 1). A two-way ANOVA with treatment (Control, Diet A, Diet B) and frequency as factors revealed significant treatment effects for ABR threshold comparisons (F=4.3, df=2,154; p=0.016). Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons revealed group differences were statistically reliable for comparisons between Control Diet and Diet B (p’s <0.05). There were no reliable differences between Diet A and Control Diet, or Diets A and B. However, given the obtained variability, post-hoc power analysis revealed inadequate statistical power for comparisons including Diet A subjects and their matched controls. Because we did not achieve adequate statistical power to determine if accepting the null hypothesis (i.e., no group differences) would result in a Type I error for the Diet A comparisons, all subsequent analyses are limited to the Diet B subjects (n=7) and their controls (n=9).

Figure 1.

The Diet B combination of nutrients significantly reduced permanent threshold shift (PTS) in treated animals compared to animals maintained on Control Diet; pair-wise comparisons revealed statistically significant differences between animals treated with Diet B and animals maintained on Control diet at 10 and 20 kHz (** p’s<0.01). At 28.3 kHz, there was a trend towards less hearing less in animals maintained on Diet B (0.05<p<0.10). There were no statistically reliable group differences during comparisons between animals maintained on Diet A and those maintained on other diets (Control, or Diet B). However, statistical power was inadequate for comparisons including Diet A, and thus, it remains possible that differences might emerge with increased sample sizes. Data are mean ± S.E.M. For Control Diet, Diet A, and Diet B subjects, data are as follows: 5 kHz, 22.5+/−3.5, 26.3+/−4.0; 15.7+/−3.4; 10 kHz: 47.8+/−4.6, 38.1+/−9.0, 20.3+/−9.3; 20 kHz: 51.9+/−3.3, 42.3+/−7.2, 38.7+/−6.9; 28.6 kHz: 49.1+/−2.4, 46.6+/−5.0, 38.4+/−4.9; and 40 kHz: 49.8+/−1.6, 46.0+/−5.7; 52.0+/−2.3.

At 10 and 20 kHz, threshold shifts in animals maintained on Diet B were significantly smaller than in animals maintained on Control Diet (p’s<0.01), with a trend for less PTS at 28.3 kHz as well (p<0.10). Taken together, PTS measured 14–16 days post-noise was significantly smaller in animals treated with the Diet B combination of antioxidant agents and magnesium, with at least 10–20 dB reduction in threshold shift at 10–20 kHz compared to controls. While PTS in animals maintained on Diet A appeared to be intermediate to that measured in Control subjects and those maintained on Diet B, suggesting a dose-dependent protection, there was not adequate power to resolve group differences for comparisons including animals maintained on Diet A.

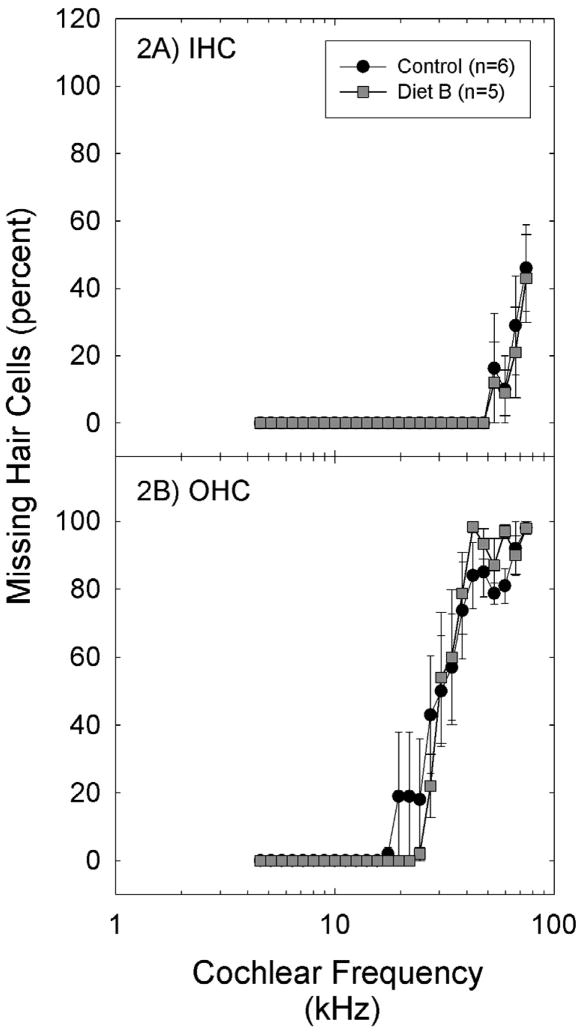

Hair cell survival

The pattern of hair cell death in both treated and control ears was consistent with damage described in other studies (87). At least for exposures that do not breach the reticular lamina, mice are somewhat less prone to hair cell loss than other mammalian species (87, 91). Hair cell loss in both Control Diet and Diet B subject groups was largely restricted to higher frequency regions of the cochlea; this pattern of loss is expected based on the noise exposure used. Inner hair cell (IHC) loss was minimal and was observed only in regions corresponding to frequencies above 50 kHz (see Figure 2A). Outer hair cell (OHC) loss was more marked (Figure 2B), with the greatest OHC loss observed in regions corresponding to frequencies of approximately 30 kHz and above (based on the tonotopic map of the mouse cochlea proposed by 92).

Figure 2.

Missing hair cells were detected in the basal regions of the cochlea, with 50% or greater OHC loss in regions corresponding to approximately 30 kHz and above (based on the tonotopic map of the mouse cochlea proposed by 92) in all groups (A: inner hair cells; B: outer hair cells). There were no reliable differences in hair cell count data as a function of treatment. Data are mean ± S.E.M.

Statistical analysis of the OHC count data via two-way ANOVA using diet and cochlear place as factors revealed a main effect for cochlear place (F=47.7, df=25,268; p<0.001) but no effect of diet was detected (p=0.871), and there was not a reliable interaction between cochlear location and diet (p=0.989). IHC outcomes were similar: there was a main effect for cochlear place (F=10.2, df=25,262; p<0.001) but no effect of diet (p=0.419), and no reliable interaction between cochlear location and diet (p=1.000). Taken together, while the Diet B dietary supplement reduced functional deficits at 10 and 20 kHz, there was no evidence that functional protection was accompanied by improved hair cell survival. Based on our methods we cannot rule out significant preservation of more subtle features such as hair cell shape, stereociliary stiffness, or conformation of the organ of Corti.

Lateral wall cell morphology

Effects of noise on CBA/J mouse cochleae have been shown to include loss of Type II fibrocytes as well as changes in stria vascularis that include epithelial thinning, basal cell loss, and capillary loss (86). Given also that oxidative stress has been reported in the lateral wall after noise insult, mid-modiolar sections were evaluated for potential antioxidant protection of cells in the lateral wall. A typical radial view of a section taken from the 10 kHz region is shown in Figure 3; the tissues shown here were harvested from an animal treated with Diet B. The region shown corresponds to a frequency at which significant PTS was observed in controls, and a frequency at which significant protection was obtained in animals maintained on Diet B (Fig. 1). This region lies somewhat apical to those regions showing overt OHC loss (which were largely regions corresponding to 30 kHz and above, see Figure 2). Accordingly, the overall appearance of the organ of Corti (Fig. 3A and D) and spiral ganglion (Fig. 3A) was normal and indistinguishable between treated and control mice within the 10 kHz region shown in Figure 3. Stria vascularis appears normal (Fig. 3B), as do Type II fibrocytes (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

A. Example radial view of the cochlear upper basal turn (approx. 10 kHz region) from an animal treated with Diet B. B.-D. show expanded views of insets. The most obvious correlates of NIHL at this location were loss of fibrocytes from the spiral limbus (SpLim in 3A) and from extreme inferior ligament. These losses were not significantly reduced by treatment. Other effects of noise, and their differences by group, were subtle. Stria vascularis (StV in 3B) appeared generally intact, but retained more basal cells in treated mice (see Fig. 4B). Treated mice also showed significantly greater retention of Type II fibrocytes (TII in 3C; see Fig. 4A). Since hair cell and neuronal losses occurred more basally than the region shown (Fig. 2), the organ of Corti (3D) appeared normal. RM: Reissner’s Membrane; TM: Tectorial Membrane; SpLig: Spiral Ligament; DC: Deiters’ Cells; IP/OP: Inner and Outer Pillar.

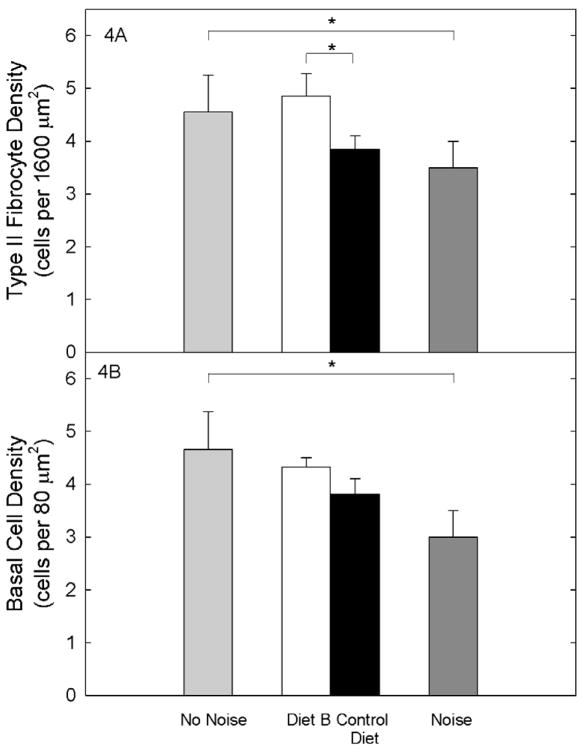

Careful quantification revealed subtle differences in survival of these latter cell types in the upper base. Lateral wall metrics revealed that the number of Type II fibrocytes was significantly greater in CBA/J subjects fed Diet B compared to mice maintained on Control Diet (t=3.2, df=11; p=0.008; see Figure 4A). In fact, Type II fibrocyte density post-noise was equivalent to that reported previously in normal CBA/J mice that had not been exposed to noise (“No Noise”). Data from our noise-exposed animals maintained on Control Diet were generally equivalent to previous data from similarly exposed CBA/J mice (86; 4–45 kHz, 110 dB SPL, 2 hours). A difference in strial cell density by treatment was also suggested, but was not statistically reliable (t=1.9, df=11; p=0.08; see Figure 4B). Density of Type I fibrocytes, and strial intermediate and marginal cells, were also quantified in the upper basal turn. No reliable group differences were observed (two-tailed t-tests, all p’s>0.10; not illustrated). Changes in the Type II fibrocyte population have been proposed to modulate NIHL or affect its apparent stability over time (93). Alternatively, survival of Type II and other fibrocyte types may reflect the robustness of processes within spiral ligament that preserve the function of organ of Corti. The observed protection of the Type II fibrocyte population in the cochlear upper base may therefore indicate preservation of homeostatic processes required for functional preservation at mid-range sound frequencies where the greatest protection was seen.

Figure 4.

Figure 4A. The number of Type II fibrocytes was significantly greater in noise-exposed CBA/J subjects fed Diet B compared to mice maintained on Control Diet, and was equivalent to that reported previously in normal CBA/J mice that had not been exposed to noise (“No Noise”). Figure 4B. Differences in strial cell density by treatment were suggested, but were not statistically reliable. Basal cell density post-noise was generally equivalent to that reported previously in normal CBA/J mice not exposed to noise (“No Noise,” adapted from 86). However, animals fed the Control Diet in this study also showed less noise-induced loss of basal cells than in the previous study. (*=p<0.05). Data are mean ± S.D.

General health during increased dietary nutrient intake

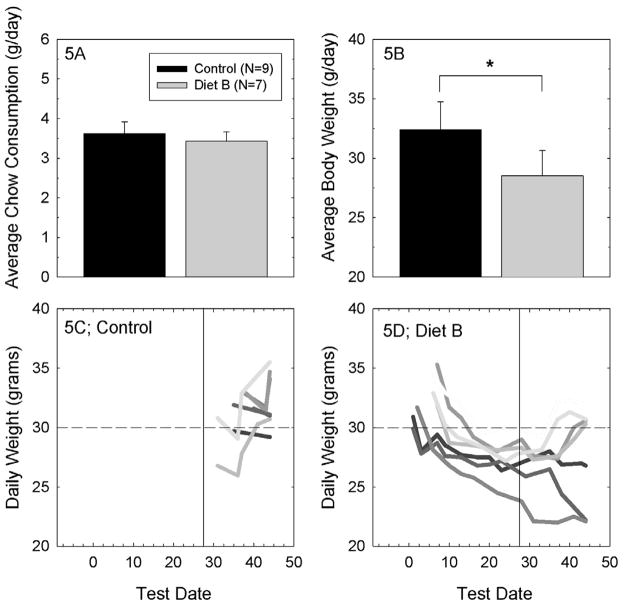

Average daily chow consumption was approximately 3.5 grams per mouse regardless of diet (see Figure 5A). However, the average weight for animals maintained on Diet B was less than that of animals maintained on Control Diet (p<0.05; see Figure 5B). To determine the extent to which group differences were a function of individual reactions to the change in diet, daily body weight measurements were plotted for the individual subjects in the Control Group (Figure 5C) and in the Diet B treatment group (Figure 5D). Control subjects, whose weight was monitored only at the late time points, generally had ending weights that were >30 grams, although there were some control subjects that did not reach 30 grams at any point during which their weight was monitored. Subjects maintained on Diet B were monitored more frequently throughout the dietary treatment window. Two subjects that had starting weights of ~30 grams lost weight throughout the duration of the study. The rest of the subjects similarly lost weight when transferred to Diet B, but their weight loss stabilized and in most cases significant weight gain was observed during the later weight assessments with longer time to adjust to the change in diet. With the exception of the two subjects that lost weight throughout the study, animals maintained on Diet B generally also had ending weights of ~30 grams. The Jackson Laboratory Database reports a normal adult weight range of 30–35 grams for CBA/J mice maintained with ad libitum access to a 6% fat diet (see 94). There was no apparent relationship between weight loss and PTS in the current cohort. The subjects that lost the most weight (Figure 5) all had hearing loss that was within the upper and lower range of data points for other animals maintained on the same diet. Thus, there did not appear to be any systematic effect of weight change on vulnerability to NIHL in this sample.

Figure 5.

Figure 5A. Average chow consumption (mean ± S.D.) did not systematically vary as a function of diet. Figure 5B. Mice that were maintained on Diet B, the diet with highest nutrient content, had a lower average body weight than mice that were maintained on the Control Diet (*=p<0.05; mean ± S.D.). Figure 5C. When daily weights for individual control animals were evaluated, we found common ending weights to be approximately 30 grams (dashed horizontal line, in panels 5C and 5D). Control animal weights were not routinely measured at earlier times. The vertical line in panels 5C and 5D indicates the day of noise exposure, on day 28 of dietary manipulation. Mice that were maintained on Diet A were generally similar to mice maintained on Control diet, with average ending weights of 32.1 grams (+/− 4.0 grams, S.D.). Figure 5D. When daily weights for individual animals maintained on Diet B were evaluated, we found common ending weights to be approximately 30 grams, although there were two mice that lost weight throughout the study (with no other significant adverse outcomes to distinguish them from other subjects). With the exception of those two subjects, most mice maintained on Diet B lost weight during the initial days during which they were maintained on this diet with subject weights returning to normal a normal range (~30 grams) with increasing time on the modified diet. The mice that lost weight while being maintained on Diet B did not systematically differ from the other mice maintained on Diet B with respect to noise-induced permanent threshold shift. Hearing loss was intermediate to other Diet B subjects.

Potential explanations for transient weight loss in animals maintained on Diet B include reduced palatability resulting in an initial decrease in consumption, and/or adverse gastrointestinal (GI) side effects. GI effects ranging from loose stools to diarrhea were observed in several animals maintained on Diet B (but not those on Control Diet or Diet A). Loose and/or watery stools could result in lower body weights if subjects had some subtle dehydration that was not detected during daily veterinary health checks. While magnesium is an essential dietary nutrient for humans, mice and other mammals, higher-level magnesium supplements have laxative effects, and are marketed as over-the-counter human laxatives. Thus, it is not surprising that high magnesium doses in mice could have similar GI effects. It seems likely that our mice received a near-maximum tolerable dose of magnesium. This may hold implications for the ultimate clinical utility of elevating systemic magnesium levels (see below).

Discussion

Treatment with β-carotene, vitamins C and E, and magnesium effectively reduces sensory cell death and corresponding PTS in guinea pigs exposed to loud noise (26). The current investigation extends these earlier findings, showing 1) functional protection against PTS in a second mammalian species, the mouse; 2) functional protection with combined agents administered via dietary supplementation rather than via injection and gavage; and 3) morphologic protection of a subset of cells in the lateral wall that are known to be damaged in the CBA/J mouse inner ear by noise exposure. Demonstration that this diet reduces damage to the inner ear after noise insult suggests an opportunity to use a diet similar to this one in other mouse studies seeking possible new interventions for other disease processes. Based on our results, however, any strategy based principally on increasing systemic levels of magnesium may ultimately prove limited by GI effects.

The current study was designed to evaluate the potential for a combination of micronutrients to mediate protection against PTS using oral administration, via dietary manipulation, which is a critical step in the ultimate translation to potential human use. Threshold shifts were the smallest in the animals maintained on the diet with the highest vitamin and magnesium content (Diet B). Animals maintained on Diet B had at least 15–20 dB reduction in threshold shift at 10–20 kHz when compared to controls. We present these data with the purpose of highlighting both the promise and the potential limitations of orally-administered protective agents. Protection previously obtained in guinea pigs was on the order of 30–35 dB reductions in PTS, thus the current protection with dietary manipulation in CBA/J mice was less robust than reported previously for treatments in guinea pigs. Those treatments were delivered using injections of a water-soluble form of vitamin E (Trolox), plus vitamin C and magnesium, with only β-carotene delivered orally (26). It is not surprising that oral dosing decreases efficacy relative to injected dosing (as has been shown for N-acetylcysteine, see 76). Additional studies with increased antioxidant content are critical for determining whether oral efficacy can be increased with higher level vitamin supplements. Differences in the level of protection in mice and guinea pigs ultimately may reflect not merely species differences and differences in the method of delivery, but also the influence of alleles specific to the CBA/J background (see 86, 95).

In addition to its intended actions, the GI complications of a high magnesium diet seen in some mice could have exerted two other general types of effects that must be considered. First, weight loss could effectively correspond to caloric restriction, which may bolster cellular stress responses (96) and could impart some protection from noise. Alternatively, weight loss could correlate with other systemic changes that impair stress responses, and thus enhance noise injury. Indeed, diarrhea typically is associated with loss of nutrients (97) and thus any GI effects with magnesium may have in fact diluted diet-mediated protection, an effect opposite to potential protection via caloric restriction. There was no apparent relationship between weight loss and PTS in the current cohort. However, anecdotal observations from another ongoing study suggests that increased weight loss is highly predictive for increased hearing loss using aminoglycosides as a model for acquired hearing loss. Taken together, the potential for benefits of caloric intake in models of acute stress to the inner ear are important to determine, and such studies will require systematic manipulation of caloric level in the absence of GI-mediated adverse events. The relationship between caloric intake and vulnerability to hearing loss may ultimately be shown to vary across insults with food restriction/weight loss being protective in chronic stress models such as aging, and food restriction/weight loss providing no protection in more acute models of stress (such as noise insult and/or drug insult).

The current data provide new evidence suggesting that combinations of dietary micronutrients delivered as dietary supplements can potentially be used to reduce PTS. Direct measurements of antioxidant levels and biochemical markers of oxidative stress in future studies are required for confirming a direct effect for antioxidant supplements on oxidative stress in the inner ear, and, given the inclusion of magnesium in this combination treatment, mechanistic studies must also include detailed exploration of the antagonism of calcium channels and preservation of blood flow to the inner ear. Other studies have already shown that vitamin A is found in the normal inner ear at higher concentrations than in other tissues (98), and that vitamin A supplements prevent JNK-activation and apoptotic cell death post-noise (99). Similarly, vitamin C supplements can prevent noise-induced nitric oxide formation in the inner ear (100), and systemic increases in glutathione and catalase measured in rabbits that received vitamin C treatments were correlated with protection against noise insult (101). Vitamin E, given systemically, reduces intra-cochlear malondialdehyde which is otherwise increased by ototoxic drug treatments (102), and direct reductions in noise-induced ROS and RNS have been measured in animals treated with a combination of Trolox and salicylate (27). Other preliminary observations provide evidence of reduced oxidative stress (measured using 3-nitrotyrosine, a marker for RNS byproducts) and reduced activation of caspase-8 both 2 hours and 7 days post-noise (103), as well as reduced translocation of endonuclease G from the mitochondria into the nucleus (104), in noise-exposed guinea pigs treated with β-carotene, vitamin C, Trolox, and magnesium prior to and after noise exposure. There are also recent data documenting reduced temporary threshold shift after less traumatic noise (105), an effect that has been previously linked to reduced excitotoxicity of the auditory nerve (106). Taken together, the dietary supplement used here could have served to mediate oxidative stress in the inner ear, it may have ameliorated noise-induced vasoconstriction via known effects of magnesium, and it is also possible that the combination may have influenced excitotoxicity. Clearly, detailed studies are required to confirm which of the multiple mechanisms of protection in fact mediated the obtained outcomes. Future studies to determine if synergistic interactions occur with long-term supplementation (as was previously demonstrated with a short-term pre-noise treatment paradigm) are also critical. The current design did not distinguish among single agent and additive or synergistic effects of combined agents. Each of the individual agents has the potential to mediate at least some of the observed protective effects (for reviews see 14, 26, 100, for more recent results, see 107).

Cellular correlates of protection

While it has been suggested that the combination of nutrients applied in this study should act in part by reducing free radical formation in OHCs, with perhaps some effect on cochlear blood flow, we found no compelling evidence of hair cell protection. This is not particularly surprising, given that there was no hair cell loss in control mice at the frequencies where robust protection of thresholds was observed. Instead of hair cell loss, the critical noise-induced damage probably included non-lethal hair cell injury, altered spatial relations within organ of Corti (87), and injury to the lateral wall (86). Noise-related changes in CBA/J and CBA/CaJ cochlear lateral wall feature fibrocyte loss (86, 90, 108) plus strial intermediate cell loss and marginal cell loss (90), and basal cell loss (86). That such damage may reflect oxidative stress is supported by detection of noise-induced free radical formation in strial marginal cells (18) and reports of intense glutathione immunoreactivity in strial basal and intermediate cells (109). Degenerative changes in cochlear lateral wall subsequent to noise have been frequently attributed to oxidative stress (110–112). Consistent with this, treatment with ascorbic acid reduced hearing loss after noise exposure as well as noise-induced nitric oxide production in the lateral wall (see 100).

The most compelling protection of inner ear microstructure in the current study was within the lateral wall. Compared to controls, CBA/J mice on Diet B had a significantly greater number of Type II fibrocytes in the spiral ligament. Cell density in treated animals was equivalent to that reported for unexposed mice. Prevention of apoptosis in the cochlear lateral wall and preservation of fibrocytes were also recently shown to preserve auditory brainstem response thresholds in the rat (113). If oxidative stress does in fact mediate damage to the cochlear lateral wall, protection of the lateral wall may represent an important additional action of antioxidant treatments against PTS. Small differences in fibrocyte survival may signal larger differences in the function of the ligament cell syncytium. It is becoming clear that gap junctions connecting cells of the lateral wall do more than accommodate potassium clearance and recycling. They may also contribute to the transfer of calcium, ATP, IP3 and other signaling molecules (for review see 93).

Considerations for future studies

Antioxidants, specifically including β-carotene, vitamins C and E, and, more recently, magnesium, have been broadly suggested as potential therapeutic agents for multiple disease conditions, and a number of investigations have been conducted using mouse models. Supplement levels have ranged widely across studies, and the supplements used in this study compare as follows.

β-carotene

In studies evaluating β-carotene, mice have been fed <10 mg β-carotene/kg chow (114), up to 12,000 mg β-carotene/kg chow (115), with 500 mg β-carotene/kg chow providing an intermediate supplement level (116, 117). The Diet B formulation used in this study included 224 mg β-carotene/kg chow (see Table 1). It is not clear how much of the protection was specifically mediated by β-carotene, as rodents do not absorb and accumulate β-carotene as efficiently as humans (118).

Vitamin C

Vitamin C has been less commonly evaluated in mouse models, given that there are compelling differences with respect to endogenous antioxidant production in most rodents when compared to the human condition. Nonetheless, it is clear that higher-level vitamin C supplements delivered to mice have enhanced ascorbic acid levels in multiple tissue types in other studies (119–121). In those studies, the Vitamin C supplements also decreased malondialdehyde, prevented ROS production, and protected endogenous superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase production (119–121). Across studies, dietary vitamin C supplements delivered to mice have typically ranged from 10–80 g/kg chow dietary supplements. The Diet B formulation used in this study included 3.6 g ascorbic acid per kg chow (see Table 1). Given evidence of protection with the current levels, future studies should explore the potential for increased protection of the inner ear with higher-level Vitamin C supplements given evidence of protection in other biological systems.

Vitamin E

Meydani et al. (122) carefully explored the effects of age and dietary fat sources (corn oil, coconut oil, and fish oil) on vitamin E absorption in mice, with dietary supplements ranging from 30 mg/kg to 5 g/kg vitamin E. Plasma tocopherol concentrations increased with dietary supplement concentration, and varied with both age (young>old) and oil additive (coconut>corn>fish). Dietary supplements delivered to mice have been somewhat variable across subsequent intervention studies. Supplements ranging from 0.585 g/kg (123) to 1.65 g/kg (124, 125) increased vitamin E levels in plasma, tissue homogenates, and mitochondria in aged mice, although there were no corresponding decreases in oxidative stress. In de la Asunción et al. (120), 0.6 g/kg dietary supplements were protective however, suggesting both age and the stress model are important variables. The Diet B formulation used in this study included 2.65 g/kg Vitamin E (see Table 1).

Magnesium

Magnesium delivered as 21.5 – 43 g/l magnesium pidolate in drinking water, had no therapeutic effect when evaluated as a potential treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in the mouse; however, magnesium levels in the brain did not change with this treatment regimen (126). In contrast to these negative results, a high-magnesium diet (approximately 1,000 mg/kg/day) resulted in increased serum and erythrocyte magnesium levels in the mouse, and had therapeutic benefits in reduction of anemia (127). Serum levels are perhaps more amenable to dietary manipulation than cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) as CSF levels did not increase with increased serum magnesium level (128). The Diet B formulation used in this study included 4.5 g/kg active magnesium, after accounting for salt weight (see Table 1). Decreased weight gain has been measured in young mice fed magnesium chloride salt supplements, with 2.5%–5% dietary concentration representing a potentially critical boundary (129).

Caloric Intake

As investigations into the potential for protection of the ear or reduction of other disease conditions continue, perhaps using even longer-term dosing strategies, it will be critical that subject weights are routinely monitored in long term studies, with diets to be modified if consumption and/or weight differences emerge across groups. The data collected in this study revealed transient weight loss in animals maintained on Diet B; weight loss during decreased protein consumption has been directly shown to enhance PTS. Specifically, guinea pigs maintained on a low protein diet lost weight and they had a decrease in endogenous glutathione production given decreased availability of glutathione precursors; this increased their susceptibility to PTS (130). If weight loss was a consequence of slightly decreased chow consumption, suggesting some small but perhaps significant decrease in overall protein intake, then the antioxidant supplements may have acted in two ways: 1) to directly reduce noise-induced oxidative stress, and 2) to counteract a decrease in endogenous glutathione production. Although one could argue that decreased food intake is in essence a mild caloric restriction, there are no data to date that directly demonstrate an effect of caloric restriction on noise-induced trauma. Although caloric restriction has reduced apoptotic cell death in the inner ear in some aged mouse strains (131), this effect has not been consistently observed across aged mouse strains (132). Although we cannot exclude the possibility that mild caloric restriction contributed to the obtained protection, it seems more likely that weight loss would have negative effects, rather than contributing to protection, given data explicitly demonstrating increased vulnerability to NIHL during decreased protein intake.

Conclusions

Taken together, the current data confirm and extend existing reports that dietary micronutrients and other antioxidant-based strategies attenuate PTS in the mammalian ear. The combination micronutrient approach has now been shown to provide benefit in both guinea pigs and mice using either oral or injected treatment paradigms. Protection has been incomplete, however, as reported for other studies. Certainly, devices that attenuate sound coming into the ear remain the preferred choice for reducing occupation-related noise and noise that occurs during other loud activities. However, it is increasingly clear that hearing loss that occurs despite use of hearing protectors, or when hearing protection cannot be used, may be effectively reduced by minimizing noise-induced oxidative stress in the inner ear using antioxidant based therapies.

Mitochondrial dysfunction and free radical production have been widely implicated across neurodegenerative syndromes and diseases, and the use of antioxidant agents is considered to hold significant therapeutic promise for many neurodegenerative processes. The similarity of free radical production across multiple neurodegenerative diseases and the putative efficacy of antioxidants in reducing neurodegenerative processes provides a compelling rationale for continued study of antioxidants to prevent PTS and possibly these other disease phenotypes. The data on use of vitamins to improve human health has been notably mixed in other disease models. For example, among high-risk individuals that were studied in a large-scale heart-protection study, antioxidant vitamins were safe but they did not produce any significant reductions in the 5-year mortality from, or incidence of, any type of vascular disease, cancer, or other major outcome even though they increased blood vitamin concentrations substantially, (38). However, confidence that this nutrient combination may hold promise for benefit to the human ear is increased by the previous demonstration that a combination of beta-carotene, vitamins C and E, and zinc reduces the progression of macular degeneration (133), a disease affecting sensory cells in the visual system, as well as demonstration that magnesium dosing reduces NIHL in human subjects (134–137).

Translational Significance.

Demonstration of functional and morphological preservation of cells in the inner ear with oral administration of this antioxidant supplemented diet supports the possibility of translation to human patients, and suggests an opportunity to evaluate antioxidant protection in other mouse models of oxidative stress-related disease and pathology.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this research were presented at the 32nd Midwinter Meeting of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology (138). The project described was supported by SBIR 1 R43 DC008710 from the National Institute On Deafness And Other Communication Disorders. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute On Deafness And Other Communication Disorders or the National Institutes of Health. This project was awarded to OtoMedicine, Inc., with subcontracts awarded to Washington University (KKO), and the University of Florida (CGL). The College of Public Health and Health Professions at the University of Florida requires the following statement for all activities with direct support from industry; “Acceptance of support does not constitute endorsement of this sponsor by the College of Public Health and Health Professions, its departments, or members of the College.” The authors thank Josef Miller and Peter Boxer for comments on earlier versions of this manuscript, and Marissa Rosa and Kari Morgenstein for editorial assistance. We also thank Mandy Dossat at the University of Florida and David Robbins at Harlan-Teklad for technical assistance.

List of Abbreviations

- AIN

American Institute of Nutrition

- ABR

Auditory Brainstem Response

- CSF

Cerebrospinal Fluid

- GI

Gastro-Intestinal

- IHC

Inner Hair Cell

- NAC

N-Acetylcysteine

- NIHL

Noise-Induced Hearing Loss

- OBN

Octave-Band Noise

- OHC

Outer Hair Cell

- PTS

Permanent Threshold Shift

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

- RNS

Reactive Nitrogen Species

- UCUCA

University Committee on the Care and Use of Animals

Footnotes

Disclosure

Dr. Le Prell is a co-inventor on US Patent Application 20090155390, which is assigned to the University of Michigan. The micronutrient treatment described in USPTO 20090155390 was licensed to OtoMedicine, Inc., at the time this study was conducted. Dr. Bennett was a founding member and an employee of OtoMedicine, Inc., and Ms. Gagnon was temporarily employed by OtoMedicine. Dr. Le Prell previously worked as a paid consultant to OtoMedicine and has disclosed this relationship to the Conflict of Interest Board at the University of Florida.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ansari MA, Scheff SW. Oxidative stress in the progression of Alzheimer disease in the frontal cortex. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010 Feb;69(2):155–67. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181cb5af4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonda DJ, Wang X, Perry G, Nunomura A, Tabaton M, Zhu X, et al. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease: A possibility for prevention. Neuropharmacology. 2010 Apr 13; doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim J, Lee HJ, Lee KW. Naturally occurring phytochemicals for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2010 Mar;112(6):1415–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rottkamp CA, Nunomura A, Hirai K, Sayre LM, Perry G, Smith MA. Will antioxidants fulfill their expectations for the treatment of Alzheimer disease? Mech Ageing Dev. 2000 Jul 31;116(2–3):169–79. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(00)00124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beal MF. Therapeutic approaches to mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009 Dec;15( Suppl 3):S189–94. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70812-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boldyrev AA, Stvolinsky SL, Fedorova TN, Suslina ZA. Carnosine as a natural antioxidant and geroprotector: from molecular mechanisms to clinical trials. Rejuvenation Res. 2010 Apr–Jun;13(2–3):156–8. doi: 10.1089/rej.2009.0923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navarro A, Boveris A. Brain mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in Parkinson’s disease. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2009 Dec;41(6):517–21. doi: 10.1007/s10863-009-9250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seet RC, Lee CY, Lim EC, Tan JJ, Quek AM, Chong WL, et al. Oxidative damage in Parkinson disease: Measurement using accurate biomarkers. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010 Feb 15;48(4):560–6. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith DJ. Mitochondrial dysfunction in mouse models of Parkinson’s disease revealed by transcriptomics and proteomics. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2009 Dec;41(6):487–91. doi: 10.1007/s10863-009-9254-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan H, Zhang ZW, Liang LW, Shen Q, Wang XD, Ren SM, et al. Treatment strategies for Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci Bull. 2010 Feb;26(1):66–76. doi: 10.1007/s12264-010-0302-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spindler M, Beal MF, Henchcliffe C. Coenzyme Q10 effects in neurodegenerative disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:597–610. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s5212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kong Q, Lin CL. Oxidative damage to RNA: mechanisms, consequences, and diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010 Jun;67(11):1817–29. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0277-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henderson D, Bielefeld EC, Harris KC, Hu BH. The role of oxidative stress in noise-induced hearing loss. Ear Hear. 2006;27(1):1–19. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000191942.36672.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Prell CG, Yamashita D, Minami S, Yamasoba T, Miller JM. Mechanisms of noise-induced hearing loss indicate multiple methods of prevention. Hear Res. 2007;226:22–43. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sha SH, Chen FQ, Schacht J. Activation of cell death pathways in the inner ear of the aging CBA/J mouse. Hear Res. 2009 Aug;254(1–2):92–9. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicotera TM, Henderson D, Zheng XY, Ding DL, McFadden SL. Reactive oxygen species, apoptosis, and necrosis in noise-exposed cochleas of chinchillas. Abs Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 1999;22:159. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamashita D, Jiang H, Schacht J, Miller JM. Delayed production of free radicals following noise exposure. Brain Res. 2004;1019:201–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamane H, Nakai Y, Takayama M, Iguchi H, Nakagawa T, Kojima A. Appearance of free radicals in the guinea pig inner ear after noise-induced acoustic trauma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1995;252(8):504–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02114761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell KCM, Meech RP, Klemens JJ, Gerberi MT, Dyrstad SSW, Larsen DL, et al. Prevention of noise- and drug-induced hearing loss with D-methionine. Hear Res. 2007;226:92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kopke RD, Jackson RL, Coleman JKM, Liu J, Bielefeld EC, Balough BJ. NAC for Noise: From the bench top to the clinic. Hear Res. 2007;226:114–25. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kopke RD, Coleman JK, Liu J, Campbell KC, Riffenburgh RH. Candidate’s thesis: enhancing intrinsic cochlear stress defenses to reduce noise-induced hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2002 Sep;112(9):1515–32. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200209000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kil J, Pierce C, Tran H, Gu R, Lynch ED. Ebselen treatment reduces noise induced hearing loss via the mimicry and induction of glutathione peroxidase. Hear Res. 2007;226:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lynch ED, Gu R, Pierce C, Kil J. Ebselen-mediated protection from single and repeated noise exposure in rat. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(2):333–7. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200402000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Prell CG, Bao J. Prevention of noise-induced hearing loss: potential therapeutic agents. In: Le Prell CG, Henderson D, Fay RR, Popper AN, editors. Noise-Induced Hearing Loss: Scientific Advances, Springer Handbook of Auditory Research. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minami SB, Yamashita D, Ogawa K, Schacht J, Miller JM. Creatine and tempol attenuate noise-induced hearing loss. Brain Res. 2007 May 7;1148:83–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Prell CG, Hughes LF, Miller JM. Free radical scavengers vitamins A, C, and E plus magnesium reduce noise trauma. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1454–63. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamashita D, Jiang H-Y, Le Prell CG, Schacht J, Miller JM. Post-exposure treatment attenuates noise-induced hearing loss. Neuroscience. 2005;134:633–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kopke RD, Weisskopf PA, Boone JL, Jackson RL, Wester DC, Hoffer ME, et al. Reduction of noise-induced hearing loss using L-NAC and salicylate in the chinchilla. Hear Res. 2000 Nov;149(1–2):138–46. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi CH, Chen K, Vasquez-Weldon A, Jackson RL, Floyd RA, Kopke RD. Effectiveness of 4-hydroxy phenyl N-tert-butylnitrone (4-OHPBN) alone and in combination with other antioxidant drugs in the treatment of acute acoustic trauma in chinchilla. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008 May 1;44(9):1772–84. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calzada C, Bizzotto M, Paganga G, Miller NJ, Bruckdorfer KR, Diplock AT, et al. Levels of antioxidant nutrients in plasma and low density lipoproteins: a human volunteer supplementation study. Free Radic Res. 1995 Nov;23(5):489–503. doi: 10.3109/10715769509065269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fetoni AR, Ferraresi A, Greca CL, Rizzo D, Sergi B, Tringali G, et al. Antioxidant protection against acoustic trauma by coadministration of idebenone and vitamin E. Neuroreport. 2008 Feb 12;19(3):277–81. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f50c66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novoselova EG, Lunin SM, Novoselova TV, Khrenov MO, Glushkova OV, Avkhacheva NV, et al. Naturally occurring antioxidant nutrients reduce inflammatory response in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009 Aug 1;615(1–3):234–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hatano M, Uramoto N, Okabe Y, Furukawa M, Ito M. Vitamin E and vitamin C in the treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008 Feb;128(2):116–21. doi: 10.1080/00016480701387132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma H, Das T, Pereira S, Yang Z, Zhao M, Mukerji P, et al. Efficacy of dietary antioxidants combined with a chemotherapeutic agent on human colon cancer progression in a fluorescent orthotopic mouse model. Anticancer Res. 2009 Jul;29(7):2421–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wambi CO, Sanzari JK, Sayers CM, Nuth M, Zhou Z, Davis J, et al. Protective effects of dietary antioxidants on proton total-body irradiation-mediated hematopoietic cell and animal survival. Radiat Res. 2009 Aug;172(2):175–86. doi: 10.1667/RR1708.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prasad KN, Cole WC, Kumar B. Multiple antioxidants in the prevention and treatment of Parkinson’s disease. J Am Coll Nutr. 1999 Oct;18(5):413–23. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1999.10718878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prasad KN, Kumar A, Kochupillai V, Cole WC. High doses of multiple antioxidant vitamins: essential ingredients in improving the efficacy of standard cancer therapy. J Am Coll Nutr. 1999 Feb;18(1):13–25. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1999.10718822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of antioxidant vitamin supplementation in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9326):23–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schafer FQ, Wang HP, Kelley EE, Cueno KL, Martin SM, Buettner GR. Comparing beta-carotene, vitamin E and nitric oxide as membrane antioxidants. Biol Chem. 2002 Mar–Apr;383(3–4):671–81. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burton GW, Joyce A, Ingold KU. Is vitamin E the only lipid-soluble, chain-breaking antioxidant in human blood plasma and erythrocyte membranes? Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983 Feb 15;221(1):281–90. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evans P, Halliwell B. Free radicals and hearing. Cause, consequence, and criteria. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999 Nov 28;884:19–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Niki E. Interaction of ascorbate and alpha-tocopherol. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1987;498:186–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb23761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niki E. Lipid antioxidants: how they may act in biological systems. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1987 Jun;8:153–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soares DG, Andreazza AC, Salvador M. Sequestering ability of butylated hydroxytoluene, propyl gallate, resveratrol, and vitamins C and E against ABTS, DPPH, and hydroxyl free radicals in chemical and biological systems. J Agric Food Chem. 2003 Feb 12;51(4):1077–80. doi: 10.1021/jf020864z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Niki E, Noguchi N, Tsuchihashi H, Gotoh N. Interaction among vitamin C, vitamin E, and beta-carotene. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995 Dec;62(6 Suppl):1322S–6S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.6.1322S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsuchihashi H, Kigoshi M, Iwatsuki M, Niki E. Action of beta-carotene as an antioxidant against lipid peroxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995 Oct 20;323(1):137–47. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niki E. Action of ascorbic acid as a scavenger of active and stable oxygen radicals. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991 Dec;54(6 Suppl):1119S–24S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.6.1119s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.D’Aquino M, Dunster C, Willson RL. Vitamin A and glutathione-mediated free radical damage: competing reactions with polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin C. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989 Jun 30;161(3):1199–203. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Traber MG, Atkinson J. Vitamin E, antioxidant and nothing more. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007 Jul 1;43(1):4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adrian M, Laurant P, Berthelot A. Effect of magnesium on mechanical properties of pressurized mesenteric small arteries from old and adult rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2004 May–Jun;31(5–6):306–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2004.03992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown RA, Ilg KJ, Chen AF, Ren J. Dietary Mg(2+) supplementation restores impaired vasoactive responses in isolated rat aorta induced by chronic ethanol consumption. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002 May 10;442(3):241–50. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Charbon GA. On vasodilators, magnesium and second messengers. J Mal Vasc. 1986;11(2):168–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.David R, Leitch IM, Read MA, Boura AL, Walters WA. Actions of magnesium, nifedipine and clonidine on the fetal vasculature of the human placenta. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996 Aug;36(3):267–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1996.tb02708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fullerton DA, Hahn AR, Agrafojo J, Sheridan BC, McIntyre RC., Jr Magnesium is essential in mechanisms of pulmonary vasomotor control. J Surg Res. 1996 Jun;63(1):93–7. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1996.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim CR, Oh W, Stonestreet BS. Magnesium is a cerebrovasodilator in newborn piglets. Am J Physiol. 1997 Jan;272(1 Pt 2):H511–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.1.H511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Landau R, Scott JA, Smiley RM. Magnesium-induced vasodilation in the dorsal hand vein. BJOG. 2004 May;111(5):446–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nagai I, Gebrewold A, Altura BT, Altura BM. Magnesium salts exert direct vasodilator effects on rat cremaster muscle microcirculation. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1988 Jul–Aug;294:194–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nishio A, Gebrewold A, Altura BT, Altura BM. Comparative vasodilator effects of magnesium salts on rat mesenteric arterioles and venules. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1989 Mar–Apr;298:139–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Teragawa H, Matsuura H, Chayama K, Oshima T. Mechanisms responsible for vasodilation upon magnesium infusion in vivo: clinical evidence. Magnes Res. 2002 Dec;15(3–4):241–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Teragawa H, Kato M, Yamagata T, Matsuura H, Kajiyama G. Magnesium causes nitric oxide independent coronary artery vasodilation in humans. Heart. 2001 Aug;86(2):212–6. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.2.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lipscomb DM, Roettger RL. Capillary constriction in cochlear and vestibular tissues during intense noise stimulation. Laryngoscope. 1973 Feb;83(2):259–63. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197302000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perlman HB, Kimura R. Cochlear blood flow and acoustic trauma. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 1962;54:99–119. doi: 10.3109/00016486209126927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thorne PR, Nuttall AL. Laser Doppler measurements of cochlear blood flow during loud sound exposure in the guinea pig. Hear Res. 1987;27(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miller JM, Ren TY, Dengerink HA, Nuttall AL. Cochlear blood flow changes with short sound stimulation. In: Axelsson A, Borchgrevink HM, Hamernik RP, Hellstrom PA, Henderson D, Salvi RJ, editors. Scientific Basis of Noise-Induced Hearing Loss. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1996. pp. 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miller JM, Yamashita D, Minami S, Yamasoba T, Le Prell CG. Mechanisms and prevention of noise-induced hearing loss. Otol Jpn. 2006;16(2):139–53. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Quirk WS, Avinash G, Nuttall AL, Miller JM. The influence of loud sound on red blood cell velocity and blood vessel diameter in the cochlea. Hear Res. 1992 Nov;63(1–2):102–7. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Quirk WS, Seidman MD. Cochlear vascular changes in response to loud noise. Am J Otol. 1995;16(3):322–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cevette MJ, Vormann J, Franz K. Magnesium and hearing. J Am Acad Audiol. 2003 May–Jun;14(4):202–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gunther T, Ising H, Joachims Z. Biochemical mechanisms affecting susceptibility to noise-induced hearing loss. Am J Otol. 1989 Jan;10(1):36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Le Prell CG, Yagi M, Kawamoto K, Beyer LA, Atkin G, Raphael Y, et al. Chronic excitotoxicity in the guinea pig cochlea induces temporary functional deficits without disrupting otoacoustic emissions. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;116:1044–56. doi: 10.1121/1.1772395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Le Prell CG, Bledsoe SC, Jr, Bobbin RP, Puel JL. Neurotransmission in the inner ear: Functional and molecular analyses. In: Jahn AF, Santos-Sacchi J, editors. Physiology of the Ear. 2. New York: Singular Publishing; 2001. pp. 575–611. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wolf FI, Trapani V, Simonacci M, Boninsegna A, Mazur A, Maier JA. Magnesium deficiency affects mammary epithelial cell proliferation: involvement of oxidative stress. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61(1):131–6. doi: 10.1080/01635580802376360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wolf FI, Trapani V, Simonacci M, Ferre S, Maier JA. Magnesium deficiency and endothelial dysfunction: is oxidative stress involved? Magnes Res. 2008 Mar;21(1):58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wolf FI, Trapani V. Cell (patho)physiology of magnesium. Clin Sci. 2008 Jan;114(1):27–35. doi: 10.1042/CS20070129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wolf FI, Maier JA, Nasulewicz A, Feillet-Coudray C, Simonacci M, Mazur A, et al. Magnesium and neoplasia: from carcinogenesis to tumor growth and progression or treatment. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007 Feb 1;458(1):24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bielefeld EC, Kopke RD, Jackson RL, Coleman JK, Liu J, Henderson D. Noise protection with N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) using a variety of noise exposures, NAC doses, and routes of administration. Acta Otolaryngology. 2007 Sep;127(9):914–9. doi: 10.1080/00016480601110188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Levine M, Conry-Cantilena C, Wang Y, Welch RW, Washko PW, Dhariwal KR, et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996 Apr 16;93(8):3704–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kappus H, Diplock AT. Tolerance and safety of vitamin E: a toxicological position report. Free Radic Biol Med. 1992;13(1):55–74. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(92)90166-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ohlemiller KK. Contributions of mouse models to understanding of age- and noise-related hearing loss. Brain Res. 2006;1091:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kujawa SG, Liberman MC. Acceleration of age-related hearing loss by early noise exposure: evidence of a misspent youth. J Neurosci. 2006;26(7):2115–23. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4985-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Julicher RH, Sterrenberg L, Haenen GR, Bast A, Noordhoek J. Sex differences in the cellular defense system against free radicals from oxygen or drug metabolites in rat. Arch Toxicol. 1984;56:83–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00349076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.El Barbary A, Altschuler RA, Schacht J. Glutathione S-transferases in the organ of Corti of the rat: Enzymatic activity, subunit composition, and immunohistochemical localization. Hear Res. 1993;71:80–90. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90023-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McFadden SL, Henselman LW, Zheng XY. Sex differences in auditory sensitivity of chinchillas before and after exposure to impulse noise. Ear Hear. 1999 Apr;20(2):164–74. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199904000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chatterjee IB, Majumder AK, Nandi BK, Subramanian N. Synthesis and some major functions of vitamin C in animals. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1975 Sep 30;258:24–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1975.tb29266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chatterjee IB. Evolution and the biosynthesis of ascorbic acid. Science. 1973 Dec 21;182(118):1271–2. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4118.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ohlemiller KK, Gagnon PM. Genetic dependence of cochlear cells and structures injured by noise. Hear Res. 2007 Feb;224(1–2):34–50. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang Y, Hirose K, Liberman MC. Dynamics of noise-induced cellular injury and repair in the mouse cochlea. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2002 Sep;3(3):248–68. doi: 10.1007/s101620020028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hequembourg S, Liberman MC. Spiral ligament pathology: a major aspect of age-related cochlear degeneration in C57BL/6 mice. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2001 Jun;2(2):118–29. doi: 10.1007/s101620010075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lang H, Schulte BA, Schmiedt RA. Endocochlear potentials and compound action potential recovery: functions in the C57BL/6J mouse. Hear Res. 2002 Oct;172(1–2):118–26. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00552-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hirose K, Liberman MC. Lateral wall histopathology and endocochlear potential in the noise-damaged mouse cochlea. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2003 Sep;4(3):339–52. doi: 10.1007/s10162-002-3036-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ou HC, Bohne BA, Harding GW. Noise damage in the C57BL/CBA mouse cochlea. Hear Res. 2000 Jul;145(1–2):111–22. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Muller M, von Hunerbein K, Hoidis S, Smolders JW. A physiological place-frequency map of the cochlea in the CBA/J mouse. Hear Res. 2005 Apr;202(1–2):63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ohlemiller KK. Recent findings and emerging questions in cochlear noise injury. Hear Res. 2008;245:5–17. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.The Jackson Laboratory. Mouse Phenome Project. 2009 [updated 2009 2009; cited July 22, 2009]; Available from: http://phenome.jax.org/pub-cgi/phenome/mpdcgi?rtn=strains/details&strainid=16.

- 95.Fernandez EA, Ohlemiller KK, Gagnon PM, Clark WW. Protection against noise-induced hearing loss in young CBA/J mice by low-dose kanamycin. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2010 Jun;11(2):235–44. doi: 10.1007/s10162-009-0204-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sinclair DA. Toward a unified theory of caloric restriction and longevity regulation. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005 Sep;126(9):987–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mata L. Diarrheal disease as a cause of malnutrition. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992 Jul;47(1 Pt 2):16–27. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chole RA. Experimental studies on the role of vitamin A in the inner ear. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1978 Jul–Aug;86(4 Pt 1):595–620. doi: 10.1177/01945998780860s411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ahn JH, Kang HH, Kim YJ, Chung JW. Anti-apoptotic role of retinoic acid in the inner ear of noise-exposed mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005 Sep 23;335(2):485–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Heinrich UR, Fischer I, Brieger J, Rumelin A, Schmidtmann I, Li H, et al. Ascorbic acid reduces noise-induced nitric oxide production in the guinea pig ear. Laryngoscope. 2008 May;118(5):837–42. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31816381ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Derekoy FS, Koken T, Yilmaz D, Kahraman A, Altuntas A. Effects of ascorbic acid on oxidative system and transient evoked otoacoustic emissions in rabbits exposed to noise. Laryngoscope. 2004 Oct;114(10):1775–9. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200410000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Teranishi M, Nakashima T, Wakabayashi T. Effects of alpha-tocopherol on cisplatin-induced ototoxicity in guinea pigs. Hear Res. 2001 Jan;151(1–2):61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(00)00080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Le Prell CG, Lang D, Joseph D, Kalantar N. Dietary nutrients attenuate cell death events in the inner ear after noise insult. Abs Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2011;34:218–219. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Goodson M. Senior Honors Thesis, Department of Psychology. Gainesville: University of Florida; 2008. Preventing noise-induced translocation of endonuclease G in auditory hair cells by antioxidant therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Le Prell CG, Dolan DF, Bennett DC, Boxer PA. Nutrient treatment and achieved plasma levels: reduction of noise-induced hearing loss at multiple post-noise test times. Translational Research. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.02.003. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yamasoba T, Pourbakht A, Sakamoto T, Suzuki M. Ebselen prevents noise-induced excitotoxicity and temporary threshold shift. Neurosci Lett. 2005;380:234–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shim HJ, Kang HH, Ahn JH, Chung JW. Retinoic acid applied after noise exposure can recover the noise-induced hearing loss in mice. Acta Otolaryngology. 2009 Mar;129(3):233–8. doi: 10.1080/00016480802226155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]