Sir,

Dystrophic calcification is a commonly described sequela of juvenile dermatomyositis. We describe a case of late onset calcification following juvenile dermatomyositis, which showed a therapeutic response with alendronate.

A 14-year-old boy, a known case of juvenile dermatomyositis, presented to us with hard nodular lesions over multiple sites of the body recurring over the previous 4 years. There was a history of occasional ulceration with discharge of a white chalky material from the lesions. The patient had been receiving intermittent treatment in the form of topical and systemic antibiotics with no significant relief.

Previously the child had a history of developing proximal myopathy with muscle weakness at the age of 2 years. He had been evaluated at that time at a tertiary care center, where all relevant investigations including muscle biopsy had been done. Based on the results the patient had been diagnosed with juvenile dermatomyositis and had been on intermittent systemic steroids for a period of 7 years (The initial diagnosis was made in a different institution, but the patient had all his past records – investigation and treatment records.) Patient at that time had presented with proximal myopathy and fever. Creatine kinase (CK) was elevated and ANA screen was positive. ANA profile results were not available. A mention of skin lesions is mainly present, but no biopsy was taken (no specific mention of Gottrons's papules/ heliotrope rash or any other specific skin lesions). The patient was diagnosed as a case of “juvenile dermatomyositis” based on the clinical features and investigation findings.

The patient's myopathy had since improved and he was completely off steroids over the last 5 years. During the present visit, the patient was otherwise normal, except for the nodules on the skin.

Clinical examination revealed multiple hard nodules over the body, some showing ulceration and discharge of a white chalky material. The largest lesion was seen over the right shoulder area [Figure 1]. Systemic examination was normal. A clinical diagnosis of dystrophic calcification, secondary to juvenile dermatomyositis was made, even though the rather late onset of the lesions was unusual. Except for the shoulder lesion, all the other nodules could fit in the “superficial pattern” seen in children. The shoulder lesion was more suggestive of the “peri-articular subcutaneous nodular” type. The other sites of calcification included bilateral elbows, right thigh and shins. All the sites, however, had smaller nodules compared to one on the right shoulder. All of them improved with treatment as well as the shoulder lesions. The shoulder lesion was highlighted because it was the largest among them.

Figure 1.

Cutaneous calcification with secondary ulceration before treatment with alendronate

The patient was investigated for the skin lesions, and for evidence of any active connective tissue disease. Hemogram, renal function, hepatic function, serum calcium, serum phosphorus (inorganic), serum parathyroid and thyroid hormone levels were all within normal limits. CK was also within the normal range. ANA profile did not show any positivity—anti-Sm, anti-Jo, anti-RNP, anti-SS-A, anti-SS-B, and anti-SCL 70 were all negative. Radiographs showed multiple areas of calcification [Figure 2] and a skin biopsy also confirmed the diagnosis of calcinosis. [Figure 3]

Figure 2.

Radiograph of right shoulder showing calcification

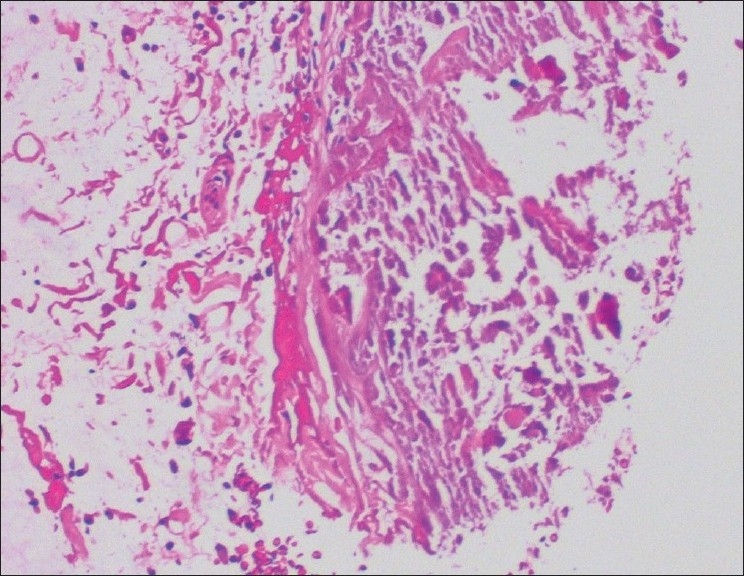

Figure 3.

Histopathology H and E, 20× showing calcium deposition

The patient was started on systemic antibiotics along with oral alendronate 10 mg once in a week. (The patient was initially put on daily 5 mg alendronate for a week, but because of gastric intolerance, the dose was changed to a weekly dose.) The patient showed remarkable improvement in the calcinosis lesions with all lesions healing and showing significant regression within a period of 2 months [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Healed lesion over the shoulder after treatment with alendronate

Dystrophic calcification is a common feature described in juvenile dermatomyositis. The incidence of calcinosis is much higher in juvenile dermatomyositis compared to adult onset disease.[1] The exact etiology of dystrophic calcification in connective tissue diseases remains unknown. One possible mechanism suggested is lysosomal damage in tissues leading to release of alkaline phosphatase, which in turn acts on organic phosphates thus precipitating calcium deposits secondary to inhibition of calcium phosphate crystallization.[2,3] Aggressive management of juvenile dermatomyositis is said to decrease the incidence of calcinosis.[4]

Various drugs have been use in treating dystrophic calcification secondary to juvenile dermatomyositis. These include diltiazem, probenicid, alendronate, warfarin, colchicine, and Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IvIg).[2,5,6] Mukamel et al. reported a case with dramatic response to alendronate. They suggest that calcinosis of juvenile dermatomyositis may be mediated by activated macrophages and that alendronate can be an effective treatment for this condition. Aledronate is speculated to exert a two-fold action by inhibiting bone resorption followed by reducing calcium turnover and by inhibiting calcium accretion in existing calcifications.[2] Ambler et al. also report a case of calcification in juvenile dermatomyositis showing a dramatic response to alendronate.[7] The surgical removal of calcinosis can be done, especially for large lesion, however, surgical trauma can stimulate calcification; therefore, it is necessary to treat a test site before proceeding further with a large excision.[8]

Our case was unusual because of the relatively late onset of calcinosis as well as the remarkable response to low-dose pulsed alendronate with in a short time.

References

- 1.Callen JP. Dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2000;355:53–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mukamel M, Horev G, Mimouni M. New insight into calcinosis of juvenile dermatomyositis: A study of composition and treatment. J Pediatr. 2001;138:763–6. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.112473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minami A, Suda K, Kaneda K, Kumakiri M. Extensive subcutaneous calcification of the forearm in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Hand Surg. 1994;19:638–41. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(94)90134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisler RE, Liang MG, Fuhlbrigge RC, Yalcindag A, Sundel RP. Aggressive management of juvenile dermatomyositis results in improved outcome and decreased incidence of calcinosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:505–11. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.122196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulman N, Slobodin G, Rozenbaum M, Rosner I. Calcinosis in rheumatic diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;34:805–12. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peñate Y, Guillermo N, Melwani P, Martel R, Hernández-Machín B, Borrego L. Calcinosis cutis associated with amyopathic dermatomyositis: Response to intravenous immunoglobulin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1076–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ambler GR, Chaitow J, Rogers M, McDonald DW, Ouvrier RA. Rapid improvement of calcinosis in juvenile dermatomyositis with alendronate therapy. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1837–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lobo IM, Machado S, Teixeira M, Selores M. Calcinosis cutis: A rare feature of adult dermatomyositis. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]