Abstract

Bacterial growth and pathogenicity depend on the correct formation of disulfide bonds, a process controlled by the Dsb system in the periplasm of Gram-negative bacteria. Proteins with a thioredoxin fold play a central role in this process. A general feature of thiol-disulfide exchange reactions is the need to avoid a long lived product complex between protein partners. We use a multidisciplinary approach, involving NMR, x-ray crystallography, surface plasmon resonance, mutagenesis, and in vivo experiments, to investigate the interaction between the two soluble domains of the transmembrane reductant conductor DsbD. Our results show oxidation state-dependent affinities between these two domains. These observations have implications for the interactions of the ubiquitous thioredoxin-like proteins with their substrates, provide insight into the key role played by a unique redox partner with an immunoglobulin fold, and are of general importance for oxidative protein-folding pathways in all organisms.

Keywords: Disulfide, NMR, Oxidation-Reduction, Protein-Protein Interactions, X-ray Crystallography, DsbD, Oxidoreductase, Thiol-Disulfide Exchange, Thioredoxin

Introduction

Oxidative protein folding, involving the formation and isomerization of disulfide bonds, is essential for the stability and function of numerous extracytoplasmic proteins in all organisms (1, 2). Correct oxidative folding is key to host-pathogen interactions and toxin secretion and, therefore, to the pathogenicity of a variety of organisms (1). Formation and breakage of disulfide bonds are simple chemical reactions. However, in vivo, these reactions are catalyzed by a range of proteins, the thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases (3, 4), which often contain the thioredoxin fold (5). In the bacterial periplasm, these proteins are maintained in the appropriate oxidation state by specific, mostly membrane-integrated, enzymes that control the oxidation state of subcellular compartments. These redox regulators (6) include DsbD, which provides the periplasm with reductant from the cytoplasm, and DsbB, which transfers reducing power in the opposite direction, from the periplasm to the respiratory chain (6, 7). Therefore, oxidative protein folding in the periplasm is the result of the concerted action of a variety of electron-transferring proteins and relies on a complex network of protein-protein interactions (Fig. 1) (6–8).

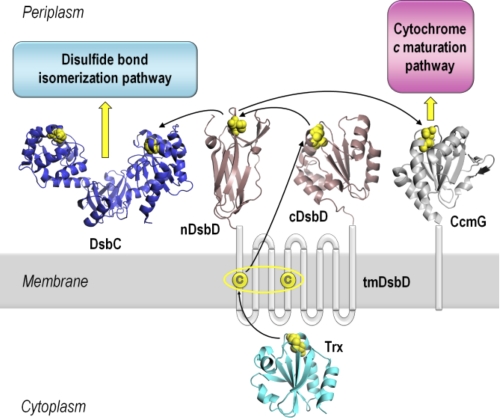

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of DsbD and its interacting partners. DsbD has three domains, a central hydrophobic domain with eight transmembrane helices (tmDsbD) and two periplasmic globular domains (nDsbD and cDsbD). The proposed pathway of electron flow from thioredoxin (Trx) in the cytoplasm, via the three domains of DsbD, to the Ccm and disulfide bond isomerization pathways in the periplasm is shown. Trxred reduces the disulfide bond in tmDsbDox, and tmDsbDred then reduces cDsbDox, which then reduces nDsbDox. DsbC, a dimeric disulfide isomerase, and CcmG, a component of the Ccm system, then accept reductant from nDsbDred. The pairs of conserved cysteines that form disulfide bonds are shown in yellow. The structures shown are from the following PDB entries: nDsbD (1JPE (16)), cDsbD (2FWF (21)), Trx (2TRX (53)), DsbC (1EEJ (54)), CcmG (2B1K (55)). All structures were rendered in PyMOL (56).

DsbD and its analog CcdA (9) are unique redox regulators; they are the only proteins known to transfer electrons from the cytoplasm to the periplasm of Gram-negative bacteria. This reducing power is required in the otherwise oxidizing periplasm for the isomerization of incorrectly formed disulfide bonds and for cytochrome c maturation (Ccm)8 (10, 11). Reductant transfer occurs via a series of sequential thiol-disulfide exchange reactions between pairs of conserved cysteines in the three domains of DsbD, tmDsbD (the integral membrane domain), nDsbD and cDsbD (the N- and C-terminal periplasmic globular domains), and their partner proteins on both sides of the inner membrane (Fig. 1) (12). The flow of electrons starts from cytoplasmic thioredoxin and proceeds to tmDsbD and then to cDsbD and nDsbD (12–15). Finally, nDsbD interacts with DsbC, for its function in the disulfide bond isomerization pathway, and CcmG, for the transfer of reductant to the Ccm pathway (7, 16–19).

X-ray structures have been determined for Escherichia coli cDsbD in both oxidation states (20, 21). It has a thioredoxin fold often found for thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases. A comparison of the structures of oxidized and reduced cDsbD shows no significant structural change apart from a reorientation of the cysteine side chains in the active site. X-ray structures have also been determined for oxidized E. coli nDsbD (16, 22). Strikingly, it has an immunoglobulin fold, a structural feature not otherwise described for a redox-active protein. No structure for reduced E. coli nDsbD has been reported to date. The crystal structure of a covalent complex of nDsbD and cDsbD has been solved (23) and has revealed the interface between them. Major conformational changes are observed between the free and bound structures of nDsbD but not for cDsbD. In particular, the cap loop (residues 66–72) of nDsbD, which shields the active-site cysteines, adopts a more open conformation in the complex.

The standard reduction potentials of the three domains of DsbD and their interacting partners indicate that all steps in DsbD-mediated electron flow from the cytoplasm to the periplasm are thermodynamically favorable (13, 23, 24). However, the standard reduction potentials of nDsbD and cDsbD are reported to be very similar (ΔE° values of 12 or 3 mV, depending on experimental conditions (13, 23), with cDsbD having the lower potential). It is expected that molecular control of the interaction is exerted in subtle ways to avoid an unproductive equilibrium between these two domains that need to react in an almost “thermodynamically neutral” step of the cascade.

We have previously used NMR to demonstrate that the pKa value of the active-site cysteine, Cys461, of cDsbD is modulated during its interaction with nDsbD, providing specificity and facilitating reductant transfer (25, 26). In the present work, we have been able to describe, using a multidisciplinary approach, how protein-protein interactions between a thioredoxin domain and a rigid immunoglobin domain depend on the oxidation states of the two partners. These interactions drive key conformational changes in the immunoglobulin domain, which therefore allows us to rationalize why this domain has been adopted for what otherwise appears to be a puzzling role in cell physiology. We anticipate that the principles established here will be applicable to a range of comparable processes in eukaryotic cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construction of DsbD Plasmids

DNA manipulations were conducted using standard methods. The construction of all plasmids is detailed in the supplemental Additional Experimental Procedures. Pwo DNA polymerase (from Pyrococcus woesei) was used for all PCRs according to the supplier's instructions (Roche Applied Science), and all constructs were sequenced and confirmed to be correct before use. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Sigma-Genosys.

Protein Production, Purification, and Characterization

Isolated wild-type cDsbD, C461A-cDsbD, V462A-cDsbD, D455N/E468Q-cDsbD, wild-type nDsbD, and C109A-nDsbD were expressed using BL21(DE3) cells (Stratagene) and were purified from periplasmic extracts of E. coli using a C-terminal His6 tag. Production and purification of all proteins was done as described in previous work (25, 26) except that 100 μg/ml ampicillin was used instead of 20 μg/ml gentamicin.

Oxidation and reduction of the single disulfide bond in each protein were carried out as follows. 5,5′-Dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) was used to oxidize the Cys103–Cys109 and Cys461–Cys464 disulfide bonds in nDsbD and cDsbD, respectively. 10 mm 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 27 °C for 30 min. Excess 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) could not be removed completely by simple concentration and redilution using a concentration device; proteins were therefore repurified using their C-terminal His6 tag, as described previously (25). Disulfide bonds in wild-type cDsbD and nDsbD samples were reduced using 10 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), the excess of which was removed by repeated concentration and redilution using a concentration device. Samples of nDsbD and cDsbD remain fully reduced at pH 6.5 for more than 24 h following removal of the excess DTT.

All proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and electrospray ionization MS to confirm that they were pure and of the expected masses. SDS-PAGE analysis was carried out on 10% BisTris NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen) using MES-SDS running buffer prepared according to Invitrogen specifications and prestained protein markers (Invitrogen, SeeBlue Plus 2). Electrospray ionization MS was performed using a Micromass Bio-Q II-ZS triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (10-μl protein samples in 1:1 water/acetonitrile, 1% formic acid at a concentration of 20 pmol/μl were injected into the electrospray source at a flow rate of 10 μl/min). Protein concentrations were determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit-Reducing Agent Compatible (Thermo Scientific), following the manufacturer's instructions.

NMR Spectroscopy

The interaction between the two soluble domains of DsbD was monitored using one-dimensional 1H and two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of mixtures of wild-type nDsbD and cDsbD, wild-type nDsbD and C461A-cDsbD, or C109A-nDsbD and wild-type cDsbD. The mixtures of the two proteins were generated by stepwise additions of the unlabeled domain into the solution of the 15N-labeled protein. Samples were prepared in 95% H2O, 5% D2O and pH 6.5. The oxidation state of nDsbD and cDsbD was strictly controlled (as described above) and was monitored from the upfield region of the 1H one-dimensional NMR spectra. Competition experiments were carried out using unlabeled protein and 1H one-dimensional NMR spectra. Aliquots of nDsbDox were added to approximately equimolar mixtures of wild-type cDsbDox and either C461A-cDsbD, V462A-cDsbDox, or D455N/E468Q-cDsbDox. All experiments were collected at 298 K unless stated otherwise. Details of NMR data collected can be found in the supplemental Additional Experimental Procedures.

Determination of Kd Values

The dissociation constant, Kd, for the nDsbDox·cDsbDox complex was calculated, using NMR data, by comparing the chemical shift changes observed for several residues of [15N]cDsbDox at each titration point (Δ) with the chemical shift changes observed for the fully bound complex of the two proteins (Δo). For [15N]cDsbDox and nDsbDox, the fully bound complex of the two domains cannot be obtained due to solubility limitations of nDsbD. The chemical shift changes measured between residues in isolated [15N]C464A-cDsbD and in the covalent mixed-disulfide complex, [15N]C464A-cDsbD-C103A-nDsbD, were used as estimates of Δo (26). The Kd value was derived from the following formula.

The reported Kd value is the average obtained from analysis of seven 1HN or 15N chemical shift changes for Gly509, Ile513, Val528, Thr529, and Phe531.

The dissociation constant, Kd, for the C109A-nDsbD·cDsbDox complex could not be determined by a titration of [15N]cDsbDox with C109A-nDsbD because of poor expression of the latter protein. Instead, the Kd was estimated from the Kd for the nDsbDox·cDsbDox complex by determining the concentration of nDsbDox that had to be added to a 0.10 mm solution of [15N]cDsbDox to achieve the same degree of broadening of the Val468 and Leu508 peaks observed for a solution containing 0.04 mm C109A-nDsbD and 0.10 mm [15N]cDsbDox.

The dissociation constant, Kd, for the nDsbDox·C461A-cDsbD complex was determined using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) data collected using a BIAcore2000 optical biosensor (Biacore, Uppsala, Sweden). Oxidized nDsbD was immobilized onto a CM5 sensor chip using the standard amine coupling procedure recommended by the manufacturer. Binding experiments were carried out using 10 mm MES buffer at pH 6.5 containing 150 mm NaCl as the running buffer. The analyte, C461A-cDsbD, was flowed over the chip surface at concentrations ranging from 0.04 to 0.5 mm. Binding of C461A-cDsbD to nDsbD immobilized on the surface of the chip was expressed in response units (RU), after subtraction of the response observed for a reference cell. The equilibrium dissociation constant, Kd, was determined by fitting the data to the equation,

where Rmax is the value of the maximal response units observed at saturation. The data gave a good fit to this equation, and a linear Scatchard plot was obtained.

Crystallization and Structure Determination for nDsbDred

Reduced nDsbD was crystallized in hanging drops by the vapor diffusion technique. The drops consisted of 1.5 μl of 10 mg/ml nDsbDred stock to which 1.5 μl of well solution was added. The crystal used for structure determination was a thick plate grown within 2 weeks at 16 °C from 28% (w/v) PEG 4000, 0.1 m ammonium sulfate, 0.1 m sodium acetate at pH 5.0, and 10 mm DTT in the well. The native data set was collected and processed as described in Table 1 and in the supplemental Additional Experimental Procedures. The structure was solved by molecular replacement (CCP4-MOLREP) (27) using the structure of oxidized nDsbD (PDB entry 1L6P) (22) as a search model.

TABLE 1.

Crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Space group | C2221 |

| Cell dimensions (Å) | 53.74 |

| 55.55 | |

| 105.21 | |

| Temperature (K) | 100 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.5418 |

| Resolution (Å) | 31.13-1.80 (1.86-1.80)a |

| Unique reflections | 14,176 |

| Redundancy | 4.1 (2.3)a |

| Rsymb (%) | 7.2 (36.6)a |

| Completeness (%) | 94.4 (72.0)a |

| I/σ(I) | 10.7 (2.1)a |

| Calculated solvent content (%) | 51.1 |

| Refinement program | REFMAC 5 |

| R factorc (%) | 18.4 |

| Rfree (%) | 23.3 |

| r.m.s. deviation from ideal bond lengths (Å) | 0.02 |

| r.m.s. deviation from ideal angles (degrees) | 1.9 |

| Average B factor (Å2) | 22.9 |

| Non-Gly/Pro residues in most favored regions | 92.3% (96/104) |

| Non-Gly/Pro residues in additionally allowed regions | 4.8% (5/104) |

| Non-Gly/Pro residues in disallowed regions | 2.9% (3/104) |

a Values in parentheses are for the outermost shell.

Rsym = Σ|Ih − 〈Ih〉|/ΣIh.

R factor = Σ(|Fo| − |Fc|)/Σ|Fo|.

Energy Minimization

The coordinates of the C103S-nDsbD-C464S-cDsbD covalent complex (PDB entry 1VRS) were used to generate models for the non-covalent complexes of nDsbD and cDsbD in the four oxidation state combinations. Ser103 and Ser464 were changed to cysteines by renaming the Oγ to Sγ. Protein structure files for X-PLOR (version 3.8) were generated with disulfide bonds or free thiols for the Cys103–Cys109 and Cys461–Cys464 pairs as appropriate. Hydrogen atoms were added to the models using the HBUILD routine in X-PLOR (28). 5000 cycles of energy minimization were carried out without constraints on hydrogen or heavy atom positions. The final energies obtained were similar for all four models. Hydrogen bonds present in each minimized structure were calculated using HBPLUS (29).

In Vivo Studies

The MC1000 (ΔDsbD) strain (30) was complemented by plasmids pDsbd1, pDsbd3, or pDsbd11 expressing full-length wild-type DsbD, C464A-DsbD, or V462A-DsbD, respectively. Cells were also transformed with plasmid pRZ001, expressing Paracoccus denitrificans cytochrome cd1, the cytochrome c chosen to assess the activity of DsbD. pRZ001 was produced by cloning the nirS gene into pEG278 (31). The MC1000 parental strain, transformed with pRZ001, served as a positive control. Cells were grown anaerobically, allowing the expression of the endogenous Ccm system, for 24 h in 1-liter bottles at 37 °C without shaking, from overnight starter cultures (also grown at 37 °C); minimal salt medium (32), supplemented with 2.5 g/liter nutrient broth (Oxoid), 0.4% glycerol, 1 mg/liter thiamine, 1 ml/liter sulfur-free metal stock solution (33), 40 mm fumarate, and 5 mm nitrate, as terminal electron acceptor, was used. 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 20 μg/ml gentamicin were added, and autoinduction was used for the expression of full-length DsbD and cytochrome cd1 (34). The cells were harvested and sphaeroplasted as described (35) except that EDTA was omitted. SDS-PAGE analysis of the periplasmic fractions was carried out as described above, and gels were stained for covalently bound heme according to the method of Goodhew et al. (36). Gel loadings were normalized according to wet cell pellet weights. Densitometry was used to quantify cytochrome cd1 production using GeneSnap (SYNGENE). The linear relationship between the amount of mature cd1 present on the gel and the amount detected by densitometry was ensured by using subsaturated loading on gels (37). Five replicates of each in vivo experiment were conducted.

The expression of C464A- and V462A-DsbD (from pDsbd3 and pDsbd11, respectively) at levels comparable to that of wild-type DsbD (from pDsbd1) was confirmed by Western blotting of normalized whole cell extracts. Goat antiserum raised against the cDsbD sequence of E. coli DsbD and donkey anti-sheep alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibody (Sigma) were used as primary and secondary antibodies, respectively.

RESULTS

An understanding of the factors that control the flow of reductant from cDsbD to nDsbD requires information about the strength of the interactions between the domains in all oxidation state combinations. NMR spectroscopy is an ideal method for studying relatively low-affinity non-covalent complexes and can provide residue-specific information about protein-protein interactions.

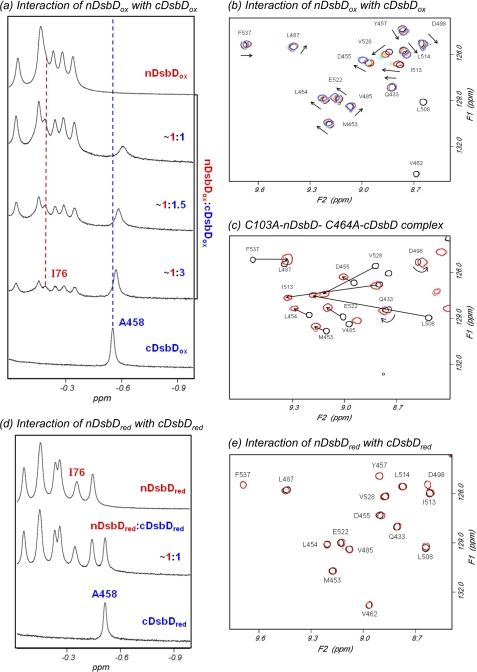

A Weak Interaction Is Observed between Oxidized nDsbD and Oxidized cDsbD

The addition of nDsbDox to [15N] cDsbDox results in an upfield shift and broadening of the peak corresponding to Hβ of Ala458, which is located close to the active site in cDsbD (Fig. 2a). Similar effects are observed for many peaks in two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of [15N]cDsbDox when nDsbDox is added (Fig. 2b). This behavior indicates a relatively weak interaction between the domains. Complementary titrations, in which unlabeled cDsbDox is added to [15N] nDsbDox, show the same behavior (supplemental Fig. S1). The chemical shift changes observed in the titrations of nDsbDox and cDsbDox are shown in supplemental Fig. S2.

FIGURE 2.

750-MHz NMR spectra of cDsbD and nDsbD show oxidation state-dependent interactions. a, titration of cDsbDox with nDsbDox, monitored by one-dimensional 1H NMR, shows fast exchange on the NMR time scale. Stepwise additions of a 1.2 mm solution of nDsbDox to a ∼0.3 mm solution of cDsbDox were made. The nDsbD concentrations were 0.09, 0.17, and 0.30 mm. As nDsbD is added, the peak corresponding to Ala458 Hβ from cDsbD broadens and shifts upfield. The peak corresponding to Ile76 Hδ of nDsbD shows similar behavior. b, two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of mixtures of [15N]cDsbDox and unlabeled nDsbDox allow the titration to be monitored at the residue-specific level. HSQC spectra were obtained during the titration of 0.3 mm [15N]cDsbDox with nDsbDox. Spectra with 0.00 (black), 0.09 (red), 0.17 (orange), 0.24 (cyan), and 0.30 mm (violet) nDsbD are shown. The arrows indicate the direction in which the peaks shift in the course of the titration. Peaks arising from Val462 and Leu508 broaden beyond detection upon the addition of 0.09 mm nDsbDox, indicating a more significant perturbation for these residues. c, overlay of HSQC spectra of [15N]C464A-cDsbD (black) and the covalent C103A-nDsbD-[15N]C464A-cDsbD complex (red) at 313 K. Peaks arising from the same residues in the two species are connected by an arrow and are labeled. In the covalent complex, peaks shift in a direction similar to that observed in b, but the magnitude of the shifts is larger in the covalent complex. d and e, cDsbDred and nDsbDred do not show a detectable interaction. d, this spectrum was obtained after the addition of 15 mm DTT to the ∼1:1 mixture of oxidized proteins shown in a, resulting in a spectrum equivalent to the sum of the spectra of isolated cDsbDred and nDsbDred. e, overlay of two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of [15N]cDsbDred (black) and the ∼1:1 mixture of [15N]cDsbDred and nDsbDred (red) shown in d. No significant broadening or peak shifts are observed, indicating that cDsbDred and nDsbDred do not show a measurable interaction with each other.

We have previously used NMR to study the covalent complex of the single-cysteine variants, C103A-nDsbD and C464A-cDsbD, and have determined chemical shift values for residues in the free and bound states of [15N]C464A-cDsbD (26); the corresponding HSQC spectra are shown in Fig. 2c. The direction in which the cDsbDox peaks shift in the titration with nDsbDox (Fig. 2b) is very similar to that observed in free C464A-cDsbD relative to the C103A-nDsbD-C464A-cDsbD covalent complex (Fig. 2c). The residues observed to be significantly perturbed in the titration of nDsbDox with cDsbDox are in agreement with predictions based on the x-ray structure of the covalent disulfide-linked complex (Fig. 3a) (23). This confirms that the non-covalent interaction between nDsbDox and cDsbDox involves the same residues and conformational changes similar to those observed in the covalent complex; thus, the biologically relevant interaction is observed by NMR. The magnitudes of the shift changes observed in the covalent complex represent the “fully bound” shift changes, and these are used to estimate a Kd value of ∼800 ± 200 μm for the interaction of nDsbDox and cDsbDox.

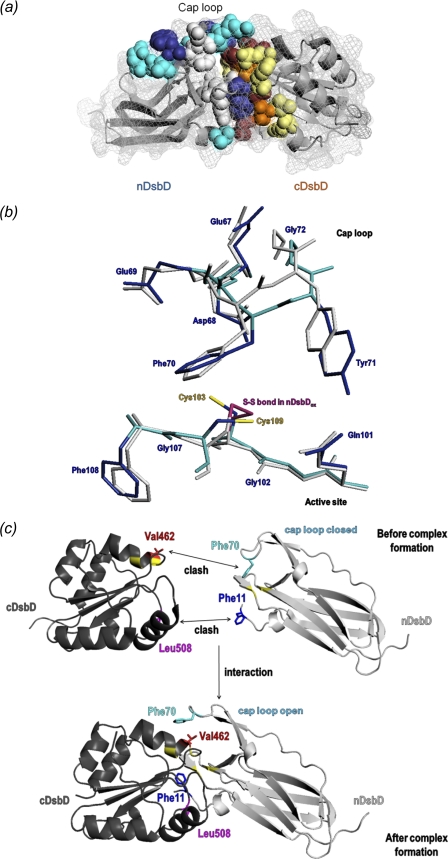

FIGURE 3.

a, chemical shift changes observed for the interaction of nDsbDox and cDsbDox are mapped onto the three-dimensional structure of the C103A-nDsbD-C464A-cDsbD complex (PDB entry 1VRS) (23). The backbone of both domains is shown as a gray ribbon, and the surface is shown as a gray mesh. Residues that are most affected by the interaction are shown in a space-filling representation. Residues with a combined chemical shift change (Δδ(HN,N); see supplemental Fig. S2) of 0.1–0.2 ppm are colored cyan (nDsbD: Val12, Gln62, Gly63, Val64, Asp68, Glu69, Ser74, and Gly102) and pale yellow (cDsbD: Cys461, Glu466, Leu510, Arg527, Val528, and Phe531); those with Δδ(HN,N) of >0.2 ppm are colored dark blue (nDsbD: Trp65, Tyr71, Gly107, and Phe108) and orange (cDsbD: Ala463, Cys464, Gly509, and Thr529); and Val462, Lys465, Leu508, and Gly530 in cDsbD that broaden beyond detection in the first titration point are colored maroon. Residues Glu67, Gln101, Cys103, Ala104, Cys109, and Tyr110 from nDsbD, which have not been assigned in the NMR spectrum due to broadening, are shown in light gray. b, superpositions of the active-site and cap-loop regions of the x-ray structures of oxidized and reduced nDsbD. Backbone and side-chain heavy atoms for nDsbDox (PDB entry 1L6P) are shown in gray. Backbone and side-chain heavy atoms for nDsbDred (PDB entry 3PFU) are shown in cyan and dark blue, respectively. The Cys103–Cys109 disulfide bond in nDsbDox is colored magenta, and the free thiols of Cys103 and Cys109 in nDsbDred are shown in yellow. c, schematic illustration of the steric clashes between Phe11 and Leu508 and between Phe70 and Val462 that result from the close approach of nDsbD and cDsbD prior to complex formation. The cap loop of nDsbD adopts an open conformation and the side-chain of Phe11 is reoriented when nDsbD and cDsbD form a complex. All structures were rendered in PyMOL (56).

No Interaction Is Observed between nDsbD and cDsbD in Their Reduced States

The addition of DTT to the end-of-titration sample of nDsbDox and cDsbDox leads to reduction of the disulfide bonds in both proteins (Fig. 2d). The observed spectrum of the mixture is a linear combination of the spectra of the two isolated reduced domains, indicating that in their reduced states the proteins show no detectable interaction. This is confirmed in the HSQC spectrum, which shows no significant peak shifts or broadening (Fig. 2e). Therefore, the interaction of nDsbD and cDsbD is oxidation state-dependent and is stronger for the oxidized relative to the reduced pair.

Interaction of Reduced cDsbD and Oxidized nDsbD before Reductant Transfer

The biologically relevant oxidation states for reductant transfer in vivo are nDsbDox and cDsbDred (12). If these are mixed in an NMR tube, reduction of nDsbDox by cDsbDred occurs before a one-dimensional NMR spectrum can be collected, resulting in a mixture containing nDsbD and cDsbD in both oxidation states. This reaction has been studied previously, and equilibrium constants of 1.4 (23) and 2.6 (13) have been reported. However, these studies were carried out at 10–1000-fold lower protein concentration and under different solution conditions from our NMR studies. The reaction is difficult to characterize quantitatively by NMR because the solution not only contains nDsbD and cDsbD in their two oxidation states but also the non-covalent complexes of nDsbD and cDsbD in various oxidation state combinations. These species can give very broad lines, making quantitation difficult. We have studied the equilibrium under NMR solution conditions using 4-acetamido-4′-maleimidylstilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid labeling and SDS-PAGE analysis (see supplemental Additional Experimental Procedures and supplemental Fig. S3). An equilibrium constant of 2.3 ± 0.1 is obtained; this is consistent with the values reported previously (13, 23).

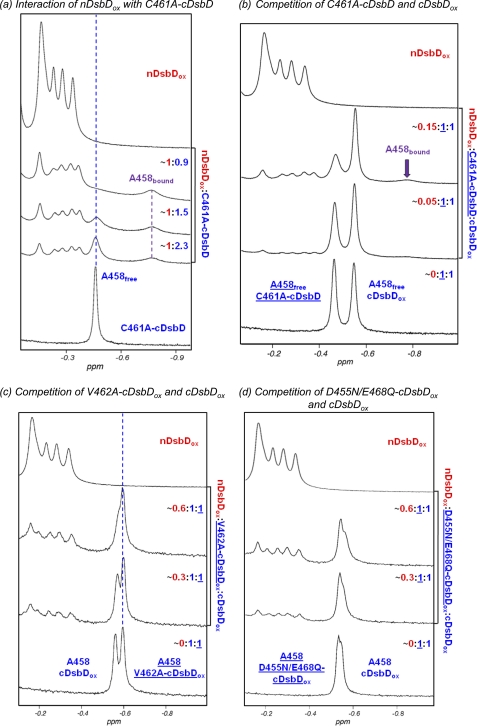

The rapid reaction between nDsbDox and cDsbDred makes study of the biologically relevant interaction difficult. We have overcome this using the C461A variant of cDsbD. Cys461 initiates nucleophilic attack on the Cys103–Cys109 disulfide of nDsbD (23), and, therefore, changing this to alanine yields a protein that mimics the reduced state but is not reactive. The titration of [15N]C461A-cDsbD with nDsbDox is illustrated in Fig. 4a. The observed behavior is substantially different from that observed for the pair of oxidized domains. The peak corresponding to Ala458 in free C461A-cDsbD broadens and decreases in intensity as nDsbDox is added, and a new peak corresponding to Ala458 in the nDsbDox-bound state of C461A-cDsbD appears at −0.77 ppm and increases in intensity as nDsbDox is added. The chemical shift difference of 0.31 ppm between the free and bound states is very similar to that observed for Ala458 between free C464A-cDsbD and the C103A-nDsbD-C464A-cDsbD covalent complex (0.29 ppm). This behavior is characteristic of slow chemical exchange and suggests a higher-affinity interaction than observed for the wild-type, oxidized pair. This is confirmed by HSQC spectra; as nDsbDox is added, the peaks corresponding to [15N]C461A-cDsbD broaden and decrease in intensity (supplemental Fig. S4). More severe broadening is observed for peaks with the largest shifts in the titration of the oxidized proteins, indicating that the same residues are involved in the interaction.

FIGURE 4.

Upfield region of 750-MHz one-dimensional 1H NMR spectra of cDsbD and nDsbD show oxidation state-dependent interactions. a, titration of C461A-cDsbD, mimicking cDsbDred, with nDsbDox shows slow exchange on the NMR time scale. Stepwise additions of a 1.2 mm stock solution of nDsbDox to a ∼0.3 mm solution of C461A-cDsbD were made. nDsbD concentrations were 0.11, 0.15, and 0.22 mm. As nDsbD is added, the peak corresponding to Ala458 broadens and decreases in intensity but does not shift. A new peak at −0.77 ppm corresponding to Ala458 in the nDsbD-bound state appears and increases in intensity. b, nDsbDox was titrated into a mixture of ∼0.3 mm C461A-cDsbD and ∼0.3 mm cDsbDox. As the concentration of nDsbDox increases from 0.015 to 0.043 mm, significant broadening is observed for the Ala458 peak of free C461A-cDsbD. The peak corresponding to Ala458 in wild-type cDsbDox is not observed to shift or broaden. This confirms that nDsbDox interacts preferentially with C461A-cDsbD. c, nDsbDox was titrated into a mixture of 0.2 mm cDsbDox and 0.2 mm V462A-cDsbDox. As the concentration of nDsbDox increases from 0.056 to 0.107 mm, the peak corresponding to Ala458 of wild-type DsbDox broadens and shifts upfield, whereas the peak corresponding to Ala458 in V462A-cDsbDox is not perturbed. This indicates that nDsbDox interacts preferentially with wild-type cDsbD. d, nDsbDox was titrated into a mixture of 0.25 mm cDsbDox and 0.25 mm D455N/E468Q-cDsbDox. As the concentration of nDsbDox increases from 0.082 to 0.144 mm, the peak corresponding to Ala458 of wild-type DsbDox broadens and shifts upfield to a more significant extent than the peak corresponding to Ala458 in D455N/E468Q-cDsbDox. This indicates that nDsbDox has a higher affinity for wild-type cDsbDox than for D455N/E468Q-cDsbDox.

The Kd for the interaction of nDsbDox and C461A-cDsbD cannot be estimated accurately by NMR due to slow chemical exchange and significant peak broadening. Instead, we have used SPR to estimate a Kd value; nDsbDox was coupled to the chip surface, and C461A-cDsbD flowed over the chip. A Kd value of 86 μm was determined (Fig. 5). This value is consistent with the NMR data (Fig. 4a) and indicates that the interaction of nDsbDox with cDsbDred is roughly an order of magnitude stronger than the interaction of the oxidized proteins. The difference in affinity of C461A-cDsbD and cDsbDox for nDsbDox was confirmed using a competition experiment. nDsbDox was added to a mixture of C461A-cDsbD and cDsbDox (Fig. 4b); significant broadening was observed for Ala458 of C461A-cDsbD with little or no effect on the Ala458 peak from cDsbDox.

FIGURE 5.

SPR data for the interaction of C461A-cDsbD with nDsbDox. a, representative sensorgrams for C461A-cDsbD binding to nDsbDox coupled to the chip surface. b, representative sensorgrams for the reference cell. The concentration of C461A-cDsbD in a and b ranged from 44 to 525 μm as indicated. c, the observed response, the difference between the response in a and b at equilibrium, is plotted as a function of the concentration of C461A-cDsbD flowed over a chip to which nDsbDox was coupled. A Kd value of 0.086 mm is obtained from a fit to these data (solid curve). d, the SPR data give a linear Scatchard plot. The solid line was calculated using the Kd value fitted in c.

cDsbD and nDsbD Interact Very Weakly following Reductant Transfer

We have studied the interaction of nDsbDred and cDsbDox, which represent the products of the disulfide- exchange reaction, using the C109A variant of nDsbD mimicking nDsbDred. The HSQC spectrum of cDsbDox following the addition of C109A-nDsbD (Fig. 6b) shows broadening of the Val462 and Leu508 peaks in cDsbDox; these are strongly perturbed in the titration of cDsbDox with nDsbDox (Fig. 2b). Thus, an interaction does occur between nDsbDred and cDsbDox. The broadening effects observed for this ∼0.4:1 mixture of C109A-nDsbD and cDsbDox are slightly greater than those observed for a ∼0.1:1 mixture of nDsbDox and cDsbDox (Fig. 6c) and somewhat less than those observed for a ∼0.14:1 mixture of nDsbDox and cDsbDox (Fig. 6d). Therefore, a higher concentration of C109A-nDsbD is required to achieve the same degree of complex formation compared with nDsbDox (Fig. 6e). This indicates that cDsbDox has a lower affinity for nDsbDred than it has for nDsbDox. Using the Kd value of ∼800 μm determined above for the interaction of cDsbDox with nDsbDox, the Kd for the interaction of cDsbDox with nDsbDred can be estimated to fall in the range of 2.4–3.5 mm. Thus, the affinity of the two protein partners in the complex present following reductant transfer, nDsbDred·cDsbDox, is ∼30–40-fold weaker than in the nDsbDox·cDsbDred complex present before reductant transfer.

FIGURE 6.

cDsbDox interacts more weakly with nDsbDred than with nDsbDox. a, two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of 0.10 mm [15N]cDsbDox. b, HSQC spectrum obtained after the addition of 0.04 mm C109A-nDsbD, mimicking nDsbDred, to 0.10 mm [15N]cDsbDox. Peaks arising from Val462 and Leu508 show significant broadening. c and d, HSQC spectrum obtained after the addition of 0.010 mm (c) and 0.014 mm (d) nDsbDox to 0.10 mm [15N]cDsbDox. The peaks corresponding to Val462 and Leu508 in b show a level of broadening that is intermediate between that observed in c and d. e, a comparison of the upfield region of 750-MHz one-dimensional 1H NMR spectra obtained for the samples shown in b (lower trace) and d (upper trace). This demonstrates that a higher concentration of C109A-nDsbD is required to achieve the same degree of complex formation compared with nDsbDox.

nDsbD and cDsbD Show Oxidation State-dependent Interaction Affinities

These NMR and SPR results clearly demonstrate that the affinity of the two periplasmic domains of DsbD is dependent on their oxidation states. The highest affinity is observed for the biologically relevant pair, nDsbDox and cDsbDred, here mimicked by C461A-cDsbD, with a Kd of 86 μm. The affinity when both domains are oxidized is ∼10-fold weaker, Kd ∼800 μm. The affinity of nDsbDred for cDsbDox, the species present following reductant transfer, is significantly lower, ∼2.4–3.5 mm. Finally, the two reduced domains do not show an interaction that is detectable in our NMR experiments. The oxidation state-dependent differences in Kd must arise as a result of either structural differences between the oxidized and reduced states or more subtle factors, such as oxidation state-specific differences in electrostatic interactions.

Comparison of Oxidized and Reduced nDsbD and cDsbD

A comparison of the high resolution x-ray structures of cDsbDox and cDsbDred (PDB entries 2FWE and 2FWF, respectively) shows no significant structural change apart from a reorientation of the cysteine side chains in the active site (21). Cα r.m.s. deviation values are below 0.4 Å for all residues with an average value of 0.13 Å (supplemental Fig. S5b). Previous analysis by NMR shows combined shift changes between oxidized and reduced cDsbD of up to ∼1.5 ppm (supplemental Fig. S5d). Combined shifts above 0.2 ppm are clustered around Cys461 and Cys464 in the active site (residues 457–468) or are located on adjacent regions of secondary structure (residues 489–492 and 513) (25, 26).

X-ray structures have been determined previously for oxidized E. coli nDsbD (16, 22) (PDB entries 1L6P and 1JPE) and for the covalent nDsbD-cDsbD complex (23) (PDB entry 1VRS). Major conformational changes are observed between the free and bound structures of nDsbD to allow the cysteine residues of nDsbD and cDsbD to interact. In particular, the cap-loop region adopts a more open conformation in the complex. To date, no structure for reduced E. coli nDsbD has been reported. However, a structure for the C103S variant of nDsbD from Neisseria meningitides has been determined using NMR (38). This structure, which mimics the reduced state, shows the cap loop in a closed conformation similar to that observed in oxidized nDsbD. The sequences of nDsbD from E. coli and N. meningitides show only 26% sequence identity and differ in several residues in the region of the cap loop and the active site. Here we have determined the structure of reduced E. coli nDsbD using x-ray crystallography at a resolution of 1.8 Å (Table 1).

Comparison of oxidized and reduced E. coli nDsbD shows differences in the region of the active-site cysteines (103 and 109) and for the cap-loop residues 66–72 (Fig. 3b and supplemental Fig. S5a). These structural changes are subtle but are sufficient to distinguish clearly the reduced and oxidized structures. In nDsbDred, the aromatic ring of Tyr42 has moved toward the space previously occupied by the disulfide bond, whereas the ring of Tyr40 has moved slightly away. The sulfur of Cys103 in nDsbDred is moderately stabilized by weak hydrogen bonds to the Tyr42 and Tyr40 hydroxyls and the Phe108 carbonyl oxygen (lengths 3.4, 3.6, and 3.4 Å, respectively). The sulfur of Cys109 is weakly hydrogen-bonded to the Gln101 amide nitrogen and the Gly102 carbonyl oxygen (lengths 3.7 Å). The largest differences in backbone conformation are observed in the cap-loop region, particularly for residues 67–73 (Cα r.m.s. deviation values >0.5 Å) (supplemental Fig. S5a). Side-chain positions in the cap loop also differ between oxidized and reduced nDsbD, side chain atoms of Phe70 show deviations of ∼1 Å, and the hydroxyl oxygen of Tyr71 moves by 1.8 Å (Fig. 3b). Despite these differences, the cap-loop region in nDsbDred is in a closed conformation, shielding the active-site cysteines from solvent.

For nDsbD in solution, combined chemical shift changes between oxidized and reduced states above 0.2 ppm are more widespread than for cDsbD (supplemental Fig. S5c). Assignments for Cys103 and Cys109 in oxidized nDsbD are missing, but large shifts are observed for Ala104 and Phe108 in the active site of nDsbD. Large changes (>0.2 ppm) are also observed for residues distant from Cys103 and Cys109 in the sequence. These include Phe11, Val12, Phe18, Arg43, and Val64–Glu75. These chemical shift changes correlate with regions of the structure showing large Cα r.m.s. deviation values between the oxidized and reduced states. The repositioning of the rings of Tyr40 and Tyr42, described above, may be responsible for the chemical shift changes in the vicinity of Arg43. The largest shift differences are observed for cap-loop residues, confirming that in solution this loop adopts different conformations in the oxidized and reduced states.

Role of the Cap-Loop Region

The cap-loop region covers the active-site cysteines in nDsbD and shields them from solvent. In the covalent complexes with its partners, this loop has a more open conformation, which makes Cys103 and Cys109 accessible to the active site of its partner proteins, cDsbD, DsbC, and CcmG. For this reason, the cap loop has been called “flexible” (15). We have studied the kinetics of reduction of nDsbDox by DTT (Fig. 7). This reaction is extremely slow, requiring ∼12 h for completion for 0.3 mm nDsbD and 3 mm DTT. By contrast, reduction of the disulfide bond in cDsbD by DTT under similar conditions happens very quickly, before an NMR spectrum can be obtained, due to the greater accessibility of the Cys461–Cys464 disulfide. This indicates that in solution, the cap loop very effectively protects the cysteines in nDsbD from DTT and may not be so flexible. NMR backbone dynamics studies of N. meningitides C103S-nDsbD show milli- to microsecond and nanosecond dynamics for Gly63 and Arg73, respectively, and picosecond dynamics for Glu65, Lys66, and Asp68 (38). However, no flexibility on a slow or fast time scale was observed for Phe70, which shields the active site (38). cDsbDred is able to reduce the Cys103–Cys109 disulfide in nDsbD several orders of magnitude faster than DTT. This suggests that cDsbD actively moves the cap loop rather than simply binding to an open conformation preexisting in solution in equilibrium with the closed form; any significant population of an open conformation would be rapidly reduced by DTT, contrary to our observation. Residues such as Gly63 and Arg73 may serve as a “hinge” that allows opening of the cap loop upon interaction with a partner protein, but this hinge remains closed in isolated nDsbD.

FIGURE 7.

Reduction of nDsbDox by DTT is a slow process. A series of one-dimensional 1H NMR spectra was collected following the addition of 3 mm DTT to 0.3 mm nDsbDox. The first spectrum was collected ∼5 min after the addition of DTT, and subsequent spectra were collected at intervals of 5 min for 16 h. The kinetics of reduction of nDsbDox by DTT can be followed by monitoring the intensity of the peak at −0.36 ppm, which corresponds to the methyl group of Ala17 in reduced nDsbD (inset). The intensity of this peak, which increases with time as nDsbD is reduced, shows pseudo-first-order kinetics with a rate constant of 0.34/h. nDsbD is only 50% reduced after ∼2 h, and full reduction takes ∼12 h.

Steric Factors Contribute to Oxidation State-dependent Affinities

Steric hindrance in the region of the active-site cysteines may contribute to the oxidation state-dependent stabilities of the nDsbD-cDsbD complexes because a pair of cysteine thiol groups is bulkier than a disulfide bond. The covalent nDsbD-cDsbD complex characterized by x-ray crystallography shows three important hydrogen bonds between the two domains that contribute to the stability of the complex; the backbone nitrogen and oxygen of Cys109 and Leu510 are involved in a pair of hydrogen bonds, and a third hydrogen bond exists between Phe531 nitrogen and Gly107 oxygen (23). We have investigated, using energy minimization, whether these hydrogen bonds can be maintained in non-covalent complexes of the four oxidation state combinations. The complex between nDsbDox and cDsbDred retains two hydrogen bonds, between Leu510 nitrogen and Cys109 oxygen and Phe531 nitrogen and Gly107 oxygen. The nDsbDox·cDsbDox and nDsbDred·cDsbDox complexes retain only the Phe531 nitrogen–Gly107 oxygen bond. The nDsbDred·cDsbDred complex loses all three hydrogen bonds in order to accommodate the four cysteine thiol groups. This result correlates with the affinities we have determined and suggests that steric factors in the active site contribute to the oxidation state-dependent affinities.

Attempts to dock the x-ray structures of free nDsbD and cDsbD in the same orientation to that observed for the covalent complex result in steric clashes involving a number of residues in the two domains. The most significant of these involve Phe11 of nDsbD with Leu508 of cDsbD and Glu69/Phe70 of nDsbD with Cys461/Val462/Glu466 of cDsbD (Fig. 3c). Val462 and Leu508 broaden and disappear from the HSQC spectrum of cDsbDox after the first addition of nDsbDox (Fig. 2b). Kim et al. suggested, on the basis of their structure of cDsbDox and the structure of the nDsbD-DsbC complex, that Val462 was likely to play a key role in the interaction of nDsbD and cDsbD (20). The side-chain methyl groups of Val462 show steric clashes with both Glu69 and Phe70, and this residue may be key to the opening of the cap loop. Interestingly, because of structural differences in the cap-loop region of nDsbD in the oxidized and reduced states, the extent of the steric clashes with cDsbD differs for nDsbDox and nDsbDred, and this may contribute to the differences in affinity. The steric clashes between Phe70 and Val462 are worse in the docked nDsbDox·cDsbDred complex than in the nDsbDred·cDsbDox complex.

nDsbD Interacts More Weakly with V462A-cDsbD than with Wild-type cDsbD

We have used mutagenesis to investigate the importance of Val462 in cDsbD. Replacement of the valine by an alanine removes the two γ methyl groups, which clash with Phe70. V462A-cDsbDred is still active and able to reduce the disulfide in nDsbDox. An 4-acetamido-4′-maleimidylstilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid labeling experiment demonstrates that the equilibrium constant and, therefore, the reduction potential are not affected by the V462A substitution (supplemental Fig. S3b). A competition experiment monitored by NMR was used to investigate the role of Val462 in the interaction of cDsbD with nDsbD. The addition of nDsbDox to an equimolar mixture of V462A-cDsbDox and wild-type cDsbDox shows line broadening and an upfield shift of the Ala458 peak from wild-type cDsbD but no perturbation to Ala458 from V462A-cDsbD (Fig. 4c). This shows clearly that nDsbDox interacts more weakly (∼5–10-fold) with V462A-cDsbDox than it does with wild-type cDsbDox and confirms the importance of Val462.

The Role of Electrostatic Effects

The structures of oxidized and reduced cDsbD are very similar (21). Thus, differences in affinity observed between nDsbDox and cDsbDox or cDsbDred must arise from other effects. We have reported previously that the pKa of Asp455 in the active site of cDsbD is 5.9 in the reduced state and 6.6 in the oxidized state (25). At the biologically relevant pH (6.5–7) cDsbDred will be more negatively charged than cDsbDox, and this may affect their affinities for nDsbD. To investigate this, we have compared the affinities of wild-type and D455N/E468Q-cDsbD for nDsbDox using a competition experiment (Fig. 4d). The Ala458 peak corresponding to wild-type cDsbD is more perturbed than the peak from D455N/E468Q-cDsbD, but the latter also shows some broadening. From a titration of D455N/E468Q-cDsbDox with nDsbDox (not shown), the Kd for this variant can be estimated to be ∼2 mm; the interaction is ∼2-fold weaker than for wild-type cDsbDox. Thus, oxidation state-dependent changes in the electrostatic properties in the active site of cDsbD contribute to the oxidation state-dependent affinities.

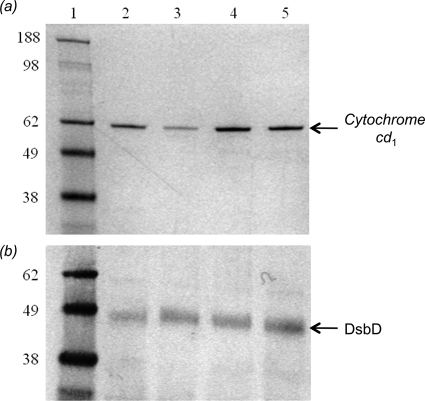

In Vivo Studies

The V462A substitution has been shown by NMR to decrease the affinity of cDsbDox for nDsbDox. We have developed an in vivo assay to test the effect of this substitution. The production of c-type cytochromes, which is dependent on reduction of CcmG by DsbD (Fig. 1), was used to assess the function of full-length DsbD in vivo. The activity of full-length V462A-DsbD was compared with that of the wild-type protein by measuring the levels of mature cytochrome cd1 in the E. coli periplasm. A dsbD deletion strain was complemented with plasmids expressing full-length wild-type, C464A- and V462A-DsbD.

Fig. 8a shows the SDS-PAGE analysis of the periplasmic extracts where cytochrome cd1 is detected by staining the gel for covalently bound heme. The level of cd1 produced when wild-type DsbD is expressed from a plasmid in the dsbD deletion strain (lane 4) is significantly higher than that produced by the endogenous protein in the parental strain (lane 2), thus ensuring the sensitivity of the experimental approach used for the quantitation. Expression of C464A-DsbD, which is inactive as it lacks one of the six essential cysteines (14), results in very low levels of cd1 production (lane 3) (39). When the cells are complemented with V462A-DsbD (lane 5) the level of cd1 maturation is ∼30% lower than observed for the wild-type protein (lane 4).

FIGURE 8.

SDS-PAGE analysis for the assessment of the activity of full-length V462A-DsbD in vivo. a, levels of cytochrome cd1 production under anaerobic growth conditions are assessed using heme staining, which detects covalently bound heme. Lane 1, molecular mass markers; lane 2, the level of cd1 production in the parental strain; lanes 3–5, the level of cd1 production in the dsbD deletion strain complemented with full-length C464A-DsbD (lane 3), wild-type DsbD (lane 4), and V462A-DsbD (lane 5) on a plasmid. b, expression levels of full-length wild-type and variant DsbDs during the anaerobic growths are assessed with a Western blot using anti-cDsbD antibody. Lane 1, molecular mass markers; lane 2, the level of full-length wild-type DsbD production in the parental strain; lanes 3–5, the levels of C464A-DsbD (lane 3), wild-type DsbD (lane 4), and V462A-DsbD (lane 5) production from a plasmid in the dsbD deletion strain.

A Western blot showing the expression levels of full-length DsbDs indicates that the variant DsbD proteins are expressed at levels comparable with that of wild-type DsbD. As shown in Fig. 8b, the amount of wild-type DsbD in the parental strain (lane 2) is lower than that in the complemented dsbD deletion strain (lane 4). Wild-type DsbD and C464A-DsbD express at the same level (lanes 4 and 3, respectively). V462A-DsbD (lane 5) expresses at a higher level than wild-type DsbD (lane 4) yet shows a lower level of cd1. The V462A mutation leads to a decrease in the activity of DsbD of at least 30%.

DISCUSSION

Relevance of Oxidation State-dependent Affinities for the Biological Function of DsbD

The affinities measured for the interaction between the two domains of DsbD are relatively low, even for the biologically relevant pair. However, in vivo nDsbD and cDsbD are held in close proximity by the intervening transmembrane domain (tmDsbD) (Fig. 1). This has the effect of significantly raising their local concentrations and rationalizes the relatively low affinities we have measured. A kinetic study of an nDsbD-cDsbD fusion construct reported an effective concentration of 0.2 mm (40). From the x-ray structure of the covalent nDsbD-cDsbD complex, we estimate an effective local concentration in vivo of ∼1 mm (see supplemental material). The difference in these estimates arises because of the length of the flexible linkers at the C terminus of nDsbD and at the N terminus of cDsbD. The previous study used a construct containing ∼40 flexible residues between the two domains, whereas our estimate is based on ∼10 flexible residues tethering each domain to tmDsbD.

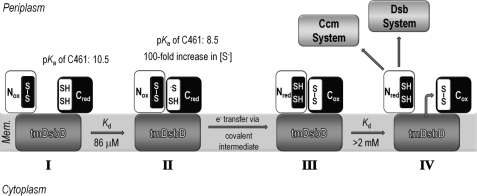

The observations made here and in previous studies enable us to propose a model to explain the periplasmic thiol-disulfide-exchange reaction of DsbD (Fig. 9). Cys461, the attacking cysteine residue in cDsbD, has an elevated pKa value of 10.5, making it a poor nucleophile and protecting it from nonspecific oxidation by other periplasmic proteins (Fig. 9I) (25, 26). An effective concentration of ∼0.2–1 mm means that nDsbDox and cDsbDred will form a productive complex in vivo (Fig. 9II); with a Kd of 86 μm, ∼70–90% of nDsbDox and cDsbDred will be present as the complex. When the nDsbDox·cDsbDred complex forms, the pKa of Cys461 is lowered, and the oxidation-reduction reaction can proceed through a mixed-disulfide intermediate (Fig. 9III) (25, 26). The low affinity of nDsbDred for cDsbDox (2.4–3.5 mm) means that once electron transfer has occurred, the product complex will dissociate (only ∼6–25% of these species present as complex). This ensures that cDsbDox is free to interact with tmDsbDred to regenerate the reactive cDsbDred, and nDsbDred is free to reduce one of its partner proteins, DsbC or CcmG (Fig. 9IV). The oxidation state dependence of the affinities of the two globular domains of DsbD ensures that nDsbD and cDsbD are not trapped in non-productive complexes that would block electron transfer from the cytoplasm to the periplasm.

FIGURE 9.

Schematic representation of the reaction cycle involving nDsbD and cDsbD. I, Cys461, the attacking cysteine residue in cDsbD, has an elevated pKa value of 10.5 when cDsbDred is distant from nDsbD (25). This makes Cys461 a poor nucleophile because essentially only the thiol species will be present and protects cDsbDred from nonspecific oxidation by other periplasmic proteins. II, the relatively high affinity of nDsbDox for cDsbDred (Kd = 86 μm) ensures formation of the nDsbDox·cDsbDred complex at the high effective concentration found in intact DsbD. In close proximity to nDsbD, the pKa value of Cys461 in cDsbDred is lowered by as much as 2 pH units (26). This increases the concentration of the reactive thiolate species (S−), making Cys461 a better nucleophile. Cys461 will attack the disulfide bond of nDsbDox, allowing electron transfer to proceed via a mixed-disulfide covalent intermediate. III, the lower affinity of the two protein partners in the nDsbDred·cDsbDox complex (Kd > 2 mm) ensures dissociation following electron transfer. IV, nDsbDred is available for reduction of its periplasmic partners CcmG and DsbC, whereas cDsbDox is available for reduction by tmDsbDred.

Consequences of Oxidation State-dependent Affinities for Other Reactions of cDsbD and nDsbD

The oxidation state-dependent affinities observed in this study provide a more general mechanism for the control of reductant flow between other protein pairs in the Dsb and Ccm systems. Because of the large effective local concentration, we expect relatively weak interactions between tmDsbD and cDsbD. This would ensure that the tmDsbD·cDsbD complex dissociates after reductant transfer, making cDsbDred available to interact with nDsbDox and tmDsbDox free to interact with reduced thioredoxin (Trxred) on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane. nDsbDred transfers electrons to CcmG and DsbC. These proteins are not covalently linked to nDsbD; therefore, a high local concentration is unlikely. We expect the affinities of these partners to be higher than observed for the nDsbD·cDsbD pair. The same would be true for the interaction of tmDsbD and Trx.

For the nDsbD and cDsbD interaction, we have suggested that steric clashes between Phe70 and Val462 and between Phe11 and Leu508 contribute to oxidation state-dependent affinities. Val462 is located in the CXXC motif of cDsbD (CVAC), and Leu508 is three residues before the cis proline, a conserved feature of thioredoxin folds. Similar “docking” calculations using the structures of free and nDsbD-bound CcmG and DsbC have identified steric clashes between Phe11 and Phe70 of nDsbD with structurally homologous residues in CcmG and DsbC. Interestingly, neither the XX in the CXXC motif nor the residues preceding the cis proline are conserved between cDsbD, CcmG, and DsbC. For CcmG, clashes are found between Phe11 and Tyr141 and between Phe70 and Pro81, located in the CPTC motif. For DsbC, clashes are found between Phe11 and Ser180 and between Phe70 and Gly99, located in the CGYC motif; additional clashes are observed between Tyr100 of the CGYC motif and Asp105 and Gly107 of nDsbD. CcmG and cDsbD, which have less bulky residues at this position, do not show steric clashes with Asp105 or Gly107. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that the steric effects involving the two XX residues of the CXXC motif play an important role in determining the specificity of interactions between nDsbD and other thioredoxins in addition to their role in modulating reduction potentials as has been suggested by others (41–43).

CONCLUSION

The mechanism by which substrate specificity of thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases is conferred in the bacterial periplasm is of particular importance because of the coexistence of reducing pathways for cytochrome c biogenesis and disulfide bond isomerization, alongside an oxidizing system for the introduction of essential disulfides into many extracellular proteins. The control of this specificity has been the subject of a number of studies. X-ray structures have been determined for several covalent mixed-disulfide complexes of the Dsb system permitting the identification of interfaces involved in complex formation (15–17, 23, 44, 45). These represent snapshots of the intermediate formed during disulfide exchange, but they do not provide information about how the proteins interact before and after the reaction. Other studies have focused on interactions between non-productive redox pairs (both proteins oxidized or reduced) or have used short peptides as mimics of one of the partners (6, 7, 44–51).

On the basis of the results presented here, we are able to understand the molecular basis for the protein-protein interactions that lead to electron transfer between cDsbD and nDsbD. The affinities that we observe for the four possible redox state pairs arise from the subtle interplay of steric and electrostatic factors. nDsbD is an oxidoreductase with a unique rigid immunoglobulin-like fold, which ensures that the active-site cysteines are only accessible after specific protein-protein interactions with its thioredoxin-like partners. For nDsbD, subtle conformational differences in the active-site and cap-loop regions affect the way it recognizes its partner proteins. In contrast, cDsbD, like other thioredoxin folds, lacks conformational changes between its oxidized and reduced states. We propose that specificity for cDsbD and other thioredoxins is exerted by means of subtle differences in electrostatics.

These results for DsbD provide insight into the factors that control the network of protein-protein interactions involving thioredoxin-like proteins and also illustrate the importance of studying interacting proteins in pairs rather than in isolation. This approach will shed light on other oxidative protein folding pathways where the protein partners might be different (e.g. in the endoplasmic reticulum or in the mitochondria of eukaryotic cells). Interestingly, Inaba and co-workers (52) have very recently reported an oxidation state-dependent interaction between human Ero1α and one of the thioredoxin domains of its partner protein-disulfide isomerase. They demonstrate that oxidized Ero1α has more than a 10-fold lower affinity for oxidized than for reduced protein-disulfide isomerase, and they conclude that this contributes to ensuring a specific and effective oxidative pathway in the ER (52). Therefore, it is likely that oxidation state-dependent affinities provide a general mechanism for the control of specificity and reactivity in pathways involving thiol-disulfide exchange reactions, which are of widespread importance in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. David Staunton for assistance with the SPR experiments.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental “Experimental Procedures” and Figs. S1–S5.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3PFU) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- Ccm

- cytochrome c maturation

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- SPR

- surface plasmon resonance

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- r.m.s.

- root mean square

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum correlation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Heras B., Shouldice S. R., Totsika M., Scanlon M. J., Schembri M. A., Martin J. L. (2009) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 215–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Riemer J., Bulleid N., Herrmann J. M. (2009) Science 324, 1284–1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Messens J., Collet J. F. (2006) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 38, 1050–1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Porat A., Cho S. H., Beckwith J. (2004) Res. Microbiol. 155, 617–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berndt C., Lillig C. H., Holmgren A. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1783, 641–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ito K., Inaba K. (2008) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18, 450–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heras B., Kurz M., Shouldice S. R., Martin J. L. (2007) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 17, 691–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vlamis-Gardikas A. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1780, 1170–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deshmukh M., Brasseur G., Daldal F. (2000) Mol. Microbiol. 35, 123–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fabianek R. A., Hennecke H., Thöny-Meyer L. (2000) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24, 303–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gleiter S., Bardwell J. C. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1783, 530–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Katzen F., Beckwith J. (2000) Cell 103, 769–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Collet J. F., Riemer J., Bader M. W., Bardwell J. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 26886–26892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gordon E. H., Page M. D., Willis A. C., Ferguson S. J. (2000) Mol. Microbiol. 35, 1360–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stirnimann C. U., Grütter M. G., Glockshuber R., Capitani G. (2006) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 63, 1642–1648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Haebel P. W., Goldstone D., Katzen F., Beckwith J., Metcalf P. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 4774–4784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stirnimann C. U., Rozhkova A., Grauschopf U., Grütter M. G., Glockshuber R., Capitani G. (2005) Structure 13, 985–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Crooke H., Cole J. (1995) Mol. Microbiol. 15, 1139–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kadokura H., Katzen F., Beckwith J. (2003) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 111–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim J. H., Kim S. J., Jeong D. G., Son J. H., Ryu S. E. (2003) FEBS Lett. 543, 164–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stirnimann C. U., Rozhkova A., Grauschopf U., Böckmann R. A., Glockshuber R., Capitani G., Grütter M. G. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 358, 829–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goulding C. W., Sawaya M. R., Parseghian A., Lim V., Eisenberg D., Missiakas D. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 6920–6927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rozhkova A., Stirnimann C. U., Frei P., Grauschopf U., Brunisholz R., Grütter M. G., Capitani G., Glockshuber R. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 1709–1719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rozhkova A., Glockshuber R. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 380, 783–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mavridou D. A., Stevens J. M., Ferguson S. J., Redfield C. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 370, 643–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mavridou D. A., Stevens J. M., Goddard A. D., Willis A. C., Ferguson S. J., Redfield C. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 3219–3226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. D 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brunger A. T. (1992) X-PLOR Version 3.1: A system for X-ray Crystallography and NMR, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT [Google Scholar]

- 29. McDonald I. K., Thornton J. M. (1994) J. Mol. Biol. 238, 777–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stewart E. J., Katzen F., Beckwith J. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 5963–5971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gordon E. H., Sjögren T., Löfqvist M., Richter C. D., Allen J. W., Higham C. W., Hajdu J., Fülöp V., Ferguson S. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11773–11781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pope N. R., Cole J. A. (1982) J. Gen. Microbiol. 128, 219–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cole J. A., Coleman K. J., Compton B. E., Kavanagh B. M., Keevil C. W. (1974) J. Gen. Microbiol. 85, 11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Studier F. W. (2005) Protein Expr. Purif. 41, 207–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ausubel F. M., Brent R., Kingston R. E., Moore D. D., Seidman J. G., Smith J. A. (1989) in Current Protocols in Molecular Biology, pp. 16.11–16.18, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goodhew C. F., Brown K. R., Pettigrew G. W. (1986) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 852, 288–294 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goddard A. D., Stevens J. M., Rao F., Mavridou D. A., Chan W., Richardson D. J., Allen J. W., Ferguson S. J. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22882–22889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Quinternet M., Tsan P., Neiers F., Beaufils C., Boschi-Muller S., Averlant-Petit M. C., Branlant G., Cung M. T. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 8577–8589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stevens J. M., Gordon E. H., Ferguson S. J. (2004) FEBS Lett. 576, 81–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rozhkova A., Glockshuber R. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 367, 1162–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chivers P. T., Prehoda K. E., Raines R. T. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 4061–4066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Heras B., Totsika M., Jarrott R., Shouldice S. R., Guncar G., Achard M. E., Wells T. J., Argente M. P., McEwan A. G., Schembri M. A. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 18423–18432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Krause G., Lundström J., Barea J. L., Pueyo de la Cuesta C., Holmgren A. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 9494–9500 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Inaba K., Murakami S., Suzuki M., Nakagawa A., Yamashita E., Okada K., Ito K. (2006) Cell 127, 789–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Paxman J. J., Borg N. A., Horne J., Thompson P. E., Chin Y., Sharma P., Simpson J. S., Wielens J., Piek S., Kahler C. M., Sakellaris H., Pearce M., Bottomley S. P., Rossjohn J., Scanlon M. J. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 17835–17845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kadokura H., Tian H., Zander T., Bardwell J. C., Beckwith J. (2004) Science 303, 534–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Colbert C. L., Wu Q., Erbel P. J., Gardner K. H., Deisenhofer J. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 4410–4415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Crow A., Acheson R. M., Le Brun N. E., Oubrie A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 23654–23660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Inaba K., Murakami S., Nakagawa A., Iida H., Kinjo M., Ito K., Suzuki M. (2009) EMBO J. 28, 779–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Inaba K., Ito K. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1783, 520–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pan J. L., Sliskovic I., Bardwell J. C. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 377, 1433–1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Masui S., Vavassori S., Fagioli C., Sitia R., Inaba K. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 16261–16271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Katti S. K., LeMaster D. M., Eklund H. (1990) J. Mol. Biol. 212, 167–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. McCarthy A. A., Haebel P. W., Törrönen A., Rybin V., Baker E. N., Metcalf P. (2000) Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 196–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ouyang N., Gao Y. G., Hu H. Y., Xia Z. X. (2006) Proteins 65, 1021–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. DeLano W. L. (2010) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.3r1, Schrodinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.