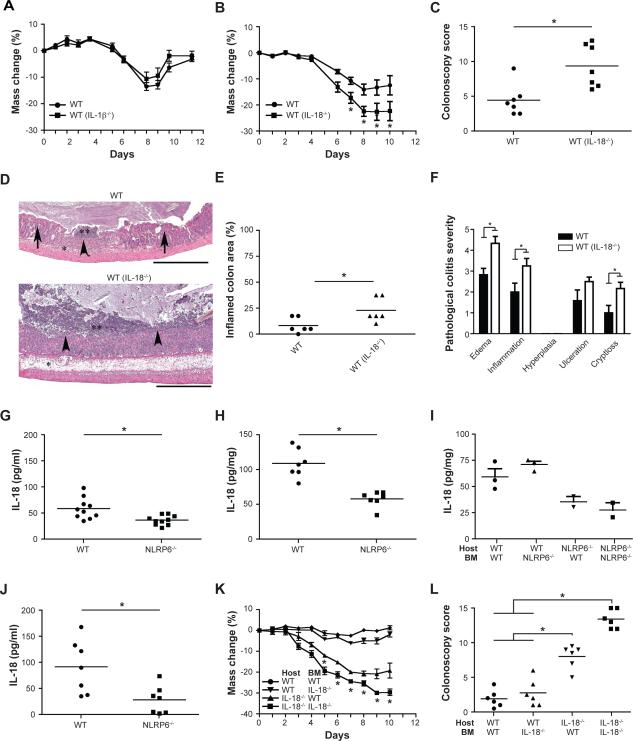

Figure 5. Processing of IL-18 by NLRP6 inflammasome suppresses colitogenic microbiota.

WT mice were cohoused with IL-1β−/− mice or IL-18−/− mice for 4 weeks and colitis was subsequently induced with DSS. Comparison of weight loss (A) in single-housed WT mice and in WT mice previously cohoused with IL-1β−/− mice (WT(IL-1β−/−)). Weight loss (B) and colonoscopy severity score at day 7 (C) for single-housed WT mice and WT mice previously cohoused with IL-18−/− mice (WT(IL-18−/−)). (D–F) Representative H&E-stained sections (D) and pathologic quantitation of disease severity (E, F) of colons from single-housed WT mice and WT mice cohoused with IL18−/− mice sampled 6 days after the start of DSS administration. Scale bars=500 μm. (G, H) IL-18 levels measured in sera (G) and colon explants (H) obtained from WT and NLRP6-deficient mice without treatment. (I) Bone-marrow chimeras were generated using both WT and NLRP6−/− mice as host and bone marrow donor. IL-18 production by colon explants was analyzed 8 weeks after bone marrow transplantation. (J) IL-18 concentrations in the serum 5 days after induction of DSS colitis. (K, L) Bone-marrow chimeras were generated using WT and IL-18−/− mice as host and bone marrow donor: weight (K) and colonoscopy severity scores at day 7 (L) of mice with acute DSS colitis are shown. Data in panels A–E are representative of at least 3 experiments, data in panels I–L are representative of two experiments (n=6 mice/samples analyzed per group). *: p<0.05 by One-way ANOVA.