Abstract

Using a constitutively active channel mutant, we solved the structure of full-length KcsA in the open conformation at 3.9 Å. The structure reveals that the activation gate expands about 20 Å, exerting a strain on the bulge helices in the C-terminal domain and generating side windows large enough to accommodate hydrated K+ ions. Functional and spectroscopic analysis of the gating transition provides direct insight into the allosteric coupling between the activation gate and the selectivity filter. We show that the movement of the inner gate helix is transmitted to the C-terminus as a straightforward expansion, leading to an upward movement and the insertion of the top third of the bulge helix into the membrane. We suggest that by limiting the extent to which the inner gate can open, the cytoplasmic domain also modulates the level of inactivation occurring at the selectivity filter.

Keywords: EPR spectroscopy, K+ channel, X-ray crystallography

Most ion channels have structured cytoplasmic domains that influence their functional behavior [in regards to both gating (1–3) and permeation (4)], contribute to their structural stability (5, 6) or allow them to directly interact with enzymes and other regulators (7). In the prokaryotic K+ channel KcsA, the 40-residue C-terminus forms a four-helix bundle that projects toward the cytoplasm (5). Removal of the C-terminus affects KcsA thermal stability, destabilizes the closed conformation (5, 6) and enhances entry into the C-type inactivated state (8). Using chaperone-assisted crystallography, we recently determined the crystal structure of full-length (FL) KcsA in its closed conformation (1). The FL KcsA structure revealed that the C-terminal domain forms a mixed twofold/fourfold symmetric, four-helix bundle that projects approximately 70 Å toward the cytoplasm and applies a steric bias on the gate, tightening the inner bundle gate and stabilizing the closed conformation (1).

In KcsA, proton dependent gating is accompanied by large movements in the helical transmembrane segment TM2. These rearrangements have been fully characterized by spectroscopic methods [EPR (9), fluorescence (10), NMR (11)], mass tagging (12), surface plasmon resonance(13) and X-ray/neutron scattering (14), and are fully consistent with available open K+ channel crystallographic structures (15, 16). However, the extent of the inner bundle gate opening, the basic set of C-terminus activation gating conformational changes and the physiological ion pathway during permeation are still not well understood in the full-length channel.

Results and Discussion

The Structure of Full-Length Open KcsA.

To determine the structure of FL KcsA in its open conformation we took advantage first, of a constitutively open mutant (17) used to generate a series of open and partially open structures of truncated KcsA (15), and second, of the availability of antibody fragments directed toward the C-terminal bundle (1). Crystals of FL KcsA-Fab2 were obtained in the orthorhombic space group I222 with two Fabs bound per tetramer and diffracted to 3.9 Å. Importantly, these crystals were highly isomorphous with the FL KcsA-Fab2 closed form (3EFF) reported earlier. Thus, a direct comparison between the open and closed forms could be made in the same unit cell using Fourier difference maps. This allows for accurate assignments of conformational changes, even at 3.9 Å resolution (Fig. S1A). Fig. 1A shows the ribbon diagram of open FL KcsA in complex with two Fab molecules. The open structure preserves the symmetry discontinuities that characterized closed FL KcsA (1), with a fourfold transmembrane region, a twofold “bulge” helix (Fig. 1A, Right Inset) and again, a fourfold symmetric canonical helical bundle at the end.

Fig. 1.

Crystal structure of FL KcsA in the open conformation. (A) Final model of the open conformation of FL KcsA with the two Fab molecules bound with a twofold noncrystallographic symmetry to the canonical four-helix bundle portion of the cytoplasmic domain. The left inset highlights a surface representation of the open conformation showing the opening of the lower gate and the creation of associated side windows for ion flow. (Right Inset) Illustrates the expansion of the Bulge helix, comprised of residues 118–135. (B) Superposition of the closed and the open conformations of FL KcsA in cartoon representation (gray), with the Bulge helix region colored orange and blue, respectively. (Left) The permeation pathway radius profile calculated with the program HOLE (18) showing the radius profile along the z axis for the closed (orange) and open (blue) conformations of FL KcsA.

As in its truncated counterpart (15), the structure of full-length KcsA in the open state is defined by a large hinge-bending motion away from the fourfold symmetry axis with the hinge toward the middle of TM2, at residue G104. Opening of the TM2 gate in FL KcsA leads to the creation of four side windows right below the gate, at the start of the bulge helix region (Fig. 1A, Left Inset). Because of the twofold symmetry, these windows are approximately 7 × 15 Å on two of the sides of the tetramer and about 5 × 10 Å in the other two. The conformational gating transition is best illustrated by overlapping FL-KcsA in its closed and open states together with the radius profile changes along the permeation pathway (Fig. 1B). The opening transition generates a per-subunit displacement of approximately 4 Å at the V115, the narrowest region of the permeation path in the closed state (1). This means that the hinge-bending movement of TM2 leads to an overall opening of approximately 21 Å at residue T112 (diagonal Cα–Cα), a value that is considerably narrower than that of the fully open truncated KcsA (approximately 32 Å) (15). In spite of the present limited resolution, a comparison of the TM2 helix reorientation between closed and open conformation suggest an approximately 15 degree rotation along the length of the helix (Fig. S1B), in agreement with the truncated channel gating rearrangements (9, 15).

Coupling Between Inner Gate and Selectivity Filter.

As expected (1), if the C-terminal domain remains as a four-helix bundle throughout KcsA gating cycle, it would probably exert a strain on the inner gate as it opens. It is not controversial then to suggest that the much larger gate opening observed in truncated KcsA might be due to the absence of this steric hindrance. It has been shown that the degree of gate opening is strictly coupled to the rate and extent of C-type inactivation at the selectivity filter (8, 15). Therefore, varying the stabilization energy of the C-terminal bundle would lead to various strain levels on the inner bundle gate, which in turn should have a differential impact on the kinetics of C-type inactivation.

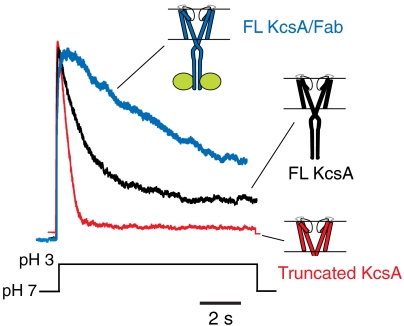

We tested this hypothesis by carrying out patch clamp experiments on reconstituted KcsA, biasing the stability of the C-terminal bundle away from WT FL KcsA by truncation (putatively no C-terminal strain on the gate), or through binding with the antibody fragment Fab4 (with additional strain imposed by the bound Fab). Fig. 2 shows that in the absence of the C-terminal domain KcsA inactivates rapidly and fully, but that the presence of the C-terminus slows down inactivation and increases three- to fourfold its steady state value. This was also seen at the single-channel level (Fig. S2). The additional strain generated by the binding of the Fab leads to an even slower inactivation rate with steady state currents that are close to 40% of the peak value. The fact that the steady state inactivation of FL KcsA displays an intermediate value between the truncated and Fab-bound forms (both with known crystal structures) has important consequences to the actual conformation of the open gate in KcsA under physiological conditions. Indeed, the inner bundle gate in WT KcsA is likely to open at an intermediate level between 21 and 32 Å, therefore generating larger side windows that easily accommodate hydrated ions and small blockers like 4-Aminopyridine and a variety of quaternary ammonium ions.

Fig. 2.

Influence of the C-terminal domain on the degree of opening of the inner bundle gate. Representative macroscopic current traces elicited in response to jumps of pH from 7.0 to pH 3.0. Currents were recorded under symmetrical 200 mM K+ at a holding membrane potential of +100 mV under conditions that putatively increase the degree of conformational flexibility at the inner bundle gate. In decreasing order: C-terminal truncated KcsA, full-length (WT) KcsA, and full-length KcsA in complex with a C-terminal bound Fab.

Mechanism of Opening.

The steric limits imposed on the C-terminal bundle conformational changes by the bound Fabs led us to study these conformational transitions using site-directed spin labeling and EPR spectroscopy (see ref. 5). Overall, the extent of spectral broadening due to dipolar coupling decreases throughout the C-terminal domain but does not disappear (Fig. S3). This confirms that the bundle expands partially but remains as a unit during opening. Fig. 3A shows a comparison of the local spin label dynamics ( ) and accessibility to the aqueous milieu (NiEdda collision frequency, ΠNiEdda) under conditions that favor the closed conformation (pH 7.0) or the open conformation (pH 3.5). When mapped onto the open FL KcsA structure (Fig. 3B) three key results emerge. First, there is no significant rotation in either the bulge helix or the lower bundle associated with the opening conformation. This suggests that the movement of the inner gate helix is transmitted to the C-terminus as a straightforward expansion. Second, the dynamics of the C-terminus increases, on average, relative to the closed state, with the largest dynamics increase at the bulge helix (black rectangle). Third, the transition region between the inner gate and the bulge helix displays a sharp decrease in NiEdda accessibility. We have interpreted this reduction as evidence of a contraction in the length of the C-terminal domain, leading to an upward movement and the insertion of the top third of the bulge helix into the membrane (Fig. 3C). This movement would be in agreement with a larger opening transition as that depicted in the FL KcsA/Fab structure.

) and accessibility to the aqueous milieu (NiEdda collision frequency, ΠNiEdda) under conditions that favor the closed conformation (pH 7.0) or the open conformation (pH 3.5). When mapped onto the open FL KcsA structure (Fig. 3B) three key results emerge. First, there is no significant rotation in either the bulge helix or the lower bundle associated with the opening conformation. This suggests that the movement of the inner gate helix is transmitted to the C-terminus as a straightforward expansion. Second, the dynamics of the C-terminus increases, on average, relative to the closed state, with the largest dynamics increase at the bulge helix (black rectangle). Third, the transition region between the inner gate and the bulge helix displays a sharp decrease in NiEdda accessibility. We have interpreted this reduction as evidence of a contraction in the length of the C-terminal domain, leading to an upward movement and the insertion of the top third of the bulge helix into the membrane (Fig. 3C). This movement would be in agreement with a larger opening transition as that depicted in the FL KcsA/Fab structure.

Fig. 3.

Spectroscopic analysis of the C-terminal domain conformational rearrangements. Structural rearrangements underlying channel opening. (A) Residue-specific environmental parameter profiles obtained in the open (red) and closed (gray) conformations for the C-terminal end of FL-KcsA: mobility parameter  (Upper), NiEdda accessibility parameter ΠNiEdda (Lower). (B) The normalized difference for each environmental parameter was mapped onto the FL-open channel structure, where increases in local dynamics or water accessibility are depicted in shades of red, whereas decreasing changes as shades of blue according to the color spectrum below. On the left, the frame highlights the large changes in local dynamics at the inner face of the bulge helix. On the right, the bar and arrow suggest that the region immediately below the activation gate might embed into the membrane upon opening. (C) A cartoon model depicting the conformational transitions of the gate and C-terminal domain in full-length KcsA upon gating. Two diagonally-related subunits are shown. Blue model, closed state; red model, open state. The gray bars represent the approximate limits of the plasma membrane.

(Upper), NiEdda accessibility parameter ΠNiEdda (Lower). (B) The normalized difference for each environmental parameter was mapped onto the FL-open channel structure, where increases in local dynamics or water accessibility are depicted in shades of red, whereas decreasing changes as shades of blue according to the color spectrum below. On the left, the frame highlights the large changes in local dynamics at the inner face of the bulge helix. On the right, the bar and arrow suggest that the region immediately below the activation gate might embed into the membrane upon opening. (C) A cartoon model depicting the conformational transitions of the gate and C-terminal domain in full-length KcsA upon gating. Two diagonally-related subunits are shown. Blue model, closed state; red model, open state. The gray bars represent the approximate limits of the plasma membrane.

Experimental Procedures

Antibody Expression and Purification.

The antibody fragment, Fab2, used in the present work is identical to that utilized to promote the crystallization of the closed conformation full-length KcsA. Its expression, purification, and handling has been described previously (1).

Crystallization and structure determination.

Full-length KcsA in the open conformation was stabilized through mutations at the pH sensor (OM-FL-KcsA), as described elsewhere (15, 17). The OM-FL-KcsA/Fab2 complex was prepared by mixing an excess Fab2 and Dodecyl-maltoside-solubilized OM-FL-KcsA and purified by gel filtration chromatography. Initial crystallization was carried using commercial screens that produced small crystals at 20 °C. Optimization of the initial condition yielded rod shape crystals using hanging drop vapor diffusion method over a well solution containing 0.2 M Na/K phosphate, 0.1 M Bis-Tris propane pH 7.5 and 10% PEG3350. The crystals were cryoprotected by passing through a series of modified well solutions with increasing amounts of glycerol. Crystals were directly flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Data were collected at beamline 23ID of Argonne National laboratory and processed by HKL2000. The structure determination was carried out with molecular replacement using both the Fab2 molecule and the closed conformation of full-length KcsA as search models. There were two Fabs and one full-length KcsA in the asymmetric unit as expected. The packing arrangement of the molecules in the lattice was identical to that of closed full-length KcsA structure. After rigid body adjustments of the Fabs and full-length KcsA, several sigmaA-weighted 2Fo-Fc omit maps were calculated to trace the helix from residue 99–160 that significantly decreased the model bias and enabled us to build the helices in their open conformation. The model is refined using CNS and the final refinement statistics are in Table 1. The final structure displayed 79.4% of its residues in the most favored regions of the Ramachandran plot, with 20.6% of residues in additional allowed regions and no residues in the disallowed regions.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics (molecular replacement)

| Full-length KcsA* |

|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | I222 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 118.2, 176.7, 340.4 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 40 (3.83) |

| Rsym or Rmerge | 0.064 (0.814) |

| I/σI | 17 (1.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 91.9 (93.9) |

| Redundancy | 4.3 (4.3) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 40-3.8 |

| No. reflections | 29,324 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.28/0.33 |

| No. atoms | |

| Protein | 1,424 |

| Ligand/ion | — |

| Water | — |

| B-factors | |

| Protein | 124 |

| Ligand/ion | — |

| Water | — |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.014 |

| Bond angles (°) | 2.29 |

*Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

KcsA Reconstitution and Liposome Patch Clamp.

After purification KcsA-Fab4 was reconstituted in asolectin liposomes as described (19). For macroscopic measurements and single-channel recording, KcsA was reconstituted in a protein:lipid ratio of 1∶100 and 1∶1000 (mass to mass), respectively. The lipids were resuspended in 200 mM KCl and 5 mM MOPS [3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid) buffer (pH 7) (5). Single-channel and macroscopic recordings were carried out as previously reported (20).

EPR Spectroscopy and Analysis.

Continuous-wave (CW) EPR spectroscopic measurements were performed at room temperature on a Bruker EMX X-band spectrometer equipped with a dielectric resonator and a gas permeable TPX plastic capillary as described (21), with an incident microwave power of 2.0 mW, modulation frequency of 100 kHz and modulation amplitude of 1.0 G.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank the members of the Perozo, Kossiakoff, and Koide labs for experimental advice and comments on the manuscript. We thank the staff at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team 24-ID-E and National Institute of General Medical Sciences and National Cancer Institute Collaborative Access Team 23ID beamlines at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-GM57846, U54 GM74946 (E.P.), and R01-GM72688 (A.A.K.) and by the University of Chicago Cancer Research Center.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

Data deposition: The crystallography, atomic coordinates, and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 3PJS).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1105112108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Uysal S, et al. Crystal structure of full-length KcsA in its closed conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6644–6649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810663106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuan P, Leonetti MD, Pico AR, Hsiung Y, MacKinnon R. Structure of the human BK channel Ca2+-activation apparatus at 3.0 A resolution. Science. 2010;329:182–186. doi: 10.1126/science.1190414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zagotta WN, et al. Structural basis for modulation and agonist specificity of HCN pacemaker channels. Nature. 2003;425:200–205. doi: 10.1038/nature01922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pegan S, et al. Cytoplasmic domain structures of Kir2.1 and Kir3.1 show sites for modulating gating and rectification. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:279–287. doi: 10.1038/nn1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortes DM, Cuello LG, Perozo E. Molecular architecture of full-length KcsA: Role of cytoplasmic domains in ion permeation and activation gating. J Gen Physiol. 2001;117:165–180. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.2.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pau VP, Zhu Y, Yuchi Z, Hoang QQ, Yang DS. Characterization of the C-terminal domain of a potassium channel from Streptomyces lividans (KcsA) J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29163–29169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan Y, Weng J, Cao Y, Bhosle RC, Zhou M. Functional coupling between the Kv1.1 channel and aldoketoreductase Kvbeta1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8634–8642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709304200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuello LG, et al. Structural basis for the coupling between activation and inactivation gates in K(+) channels. Nature. 2010;466:272–275. doi: 10.1038/nature09136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perozo E, Cortes DM, Cuello LG. Structural rearrangements underlying K+-channel activation gating. Science. 1999;285:73–78. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blunck R, Cordero-Morales JF, Cuello LG, Perozo E, Bezanilla F. Detection of the opening of the bundle crossing in KcsA with fluorescence lifetime spectroscopy reveals the existence of two gates for ion conduction. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:569–581. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker KA, Tzitzilonis C, Kwiatkowski W, Choe S, Riek R. Conformational dynamics of the KcsA potassium channel governs gating properties. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1089–1095. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly BL, Gross A. Potassium channel gating observed with site-directed mass tagging. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:280–284. doi: 10.1038/nsb908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimizu H, et al. Global twisting motion of single molecular KcsA potassium channel upon gating. Cell. 2008;132:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimmer J, Doyle DA, Grossmann JG. Structural characterization and pH-induced conformational transition of full-length KcsA. Biophys J. 2006;90:1752–1766. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.071175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuello LG, Jogini V, Cortes DM, Perozo E. Structural mechanism of C-type inactivation in K(+) channels. Nature. 2010;466:203–208. doi: 10.1038/nature09153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang Y, et al. Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Nature. 2002;417:515–522. doi: 10.1038/417515a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuello LG, et al. Design and characterization of a constitutively open KcsA. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1133–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smart OS, Neduvelil JG, Wang X, Wallace BA, Sansom MS. HOLE: A program for the analysis of the pore dimensions of ion channel structural models. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:354–360. doi: 10.1016/s0263-7855(97)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuello LG, Romero JG, Cortes DM, Perozo E. pH-dependent gating in the Streptomyces lividans K+ channel. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3229–3236. doi: 10.1021/bi972997x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cordero-Morales JF, et al. Molecular determinants of gating at the potassium-channel selectivity filter. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:311–318. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perozo E, Cortes DM, Cuello LG. Three-dimensional architecture and gating mechanism of a K+ channel studied by EPR spectroscopy. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:459–469. doi: 10.1038/nsb0698-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.