Abstract

Stem cells possess the unique capacity to differentiate into many clinically relevant somatic cell types, making them a promising cell source for tissue engineering applications and regenerative medicine therapies. However, in order for the therapeutic promise of stem cells to be fully realized, scalable approaches to efficiently direct differentiation must be developed. Traditionally, suspension culture systems are employed for the scale-up manufacturing of biologics via bioprocessing systems that heavily rely upon various types of bioreactors. However, in contrast to conventional bench-scale static cultures, large-scale suspension cultures impart complex hydrodynamic forces on cells and aggregates due to fluid mixing conditions. Stem cells are exquisitely sensitive to environmental perturbations, thus motivating the need for a more systematic understanding of the effects of hydrodynamic environments on stem cell expansion and differentiation. This article discusses the interdependent relationships between stem cell aggregation, metabolism, and phenotype in the context of hydrodynamic culture environments. Ultimately, an improved understanding of the multifactorial response of stem cells to mixed culture conditions will enable the design of bioreactors and bioprocessing systems for scalable directed differentiation approaches.

Introduction

Stem and progenitor cells have emerged as promising resources for many regenerative medicine applications, due to their potential to differentiate into multiple cells types and produce large cell yields from relatively small initial numbers of cells. Stem cells, therefore, are a promising cell source for tissue engineering, either for the direct replacement of cells lost due to degenerative diseases or traumatic injuries, or through the use of paracrine actions of trophic factors secreted by stem cells to direct regeneration of endogenous tissue.1 Additionally, stem cells serve as a flexible platform for drug screening, in which pharmaceutical companies can employ large quantities of differentiated cells for in vitro testing of cytotoxicity and for the creation of pathological tissue models.2 Ultimately, large-scale culture technologies may be required for the bioprocessing of stem cells to produce the large cell yields required for such clinical and screening applications. Bioreactor systems have been extensively utilized and validated in the bioprocessing industry, with the goal of producing high quality products on a large scale, in order to reduce handling, labor, and cost. Scalable culture formats used in tissue engineering have largely been adapted from similar bioprocessing designs, and employ chemical engineering principles, based on fluid mixing properties, to aid in the transport of nutrients and gasses within the culture volume. However, specific cell demands and quality control measures differ based on the application, and warrant adaptation of various design parameters to provide adequate transport and fluid shear profiles. Ultimately, understanding the impact of environmental perturbations, such as hydrodynamic mixing, on stem cell expansion and differentiation may be important for the rational design of bioreactors and bioprocessing systems in tissue engineering applications.

Stem cells respond to a variety of environmental cues in vitro to either maintain potency or regulate differentiation; these cues include biochemical factors (both exogenous and endogenous), cell–cell interactions, cell–matrix interactions, and mechanical stimuli. Mechanotransduction of fluid shear stress has been studied in developmental and pathological contexts due to the induction of physical, biochemical, and epigenetic cellular responses. Hemodynamic forces are important for the regulation of cardiac morphogenesis in developing embryos, where altered flow patterns result in cardiac defects.3,4 High wall shear stresses (75 dyn/cm2 at 4.5 days postfertilization) have been measured within developing cardiac structures in vivo,3 and can be correlated to specific patterns of gene regulation in endocardial tissue.5 Conversely, the development of atherosclerosis in adult vessels has been linked to regions of decreased shear stress (<4 dyn/cm2).6 As a result, the impact of fluid shear on endothelial cells has been studied extensively (extensively reviewed elsewhere7). In response to physiological magnitudes (5–15 dyn/cm2) of laminar shear stress, endothelial cells in vitro exhibit morphological changes, orient along the axis of applied flow, and remodel stress fibers.8,9 Altered gene expression, as well as release of nitric oxide and other substances involved in vasoregulation, also result from endothelial cell exposure to fluid flow.10,11 Cell metabolism is altered in the presence of turbulent flow patterns, which induce cell turnover and proliferation due to loss of contact inhibition.12 Endothelial progenitor cells similarly exhibit increased proliferation and differentiation in response to flow.13 More recent work has indicated the potential for fluid shear stress to directly alter stem cell differentiation pathways. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) differentiation along the endothelial lineage can be promoted in response to fluid flow in vitro within a parallel plate system.14 Similarly, embryonic stem cells (ESCs) cultured in the presence of fluid shear stress in monolayer exhibited increased expression of endothelial and hematopoietic markers.15–17 The mounting evidence for fluid shear stress induced modulation of stem cell phenotype and function in adherent monolayer format strongly motivates investigation of the response of three-dimensional (3D) stem cell culture to hydrodynamic environments.

Scalable Culture of Stem Cells

Stem cells

ESCs, derived from the inner cell mass of blastocyst stage embryos, were first isolated from mouse embryos,18–20 followed by the establishment of ESC lines from primate21,22 and eventually human23,24 sources. ESCs are characterized by unlimited self-renewal and pluripotent differentiation potential into all three germ layers—mesoderm, endoderm, and ectoderm—as well as into germ cells. Cells derived from murine (mESC) and human (hESC) sources share many transcriptional programs characteristic of pluripotency and differentiation, but can respond differently to extrinsic stimuli, such as leukemia inhibitory factor, a cytokine required for maintenance of mESC pluripotency.25,26 Recently, investigators have demonstrated the ability to alternatively produce pluripotent cells from various mammalian somatic cell sources by introduction of exogenous transcription factors capable of fully reprogramming the cell state.27–30 Induced pluripotent stem cells, as they are now called, exhibit many similar characteristics to ESCs with regard to differentiation and self-renewal properties, although subtle differences appear to exist between the genomic and epigenomic signature of the two pluripotent cell types.31,32

Adult stem and progenitor cells have limited self-renewal capacity and possess multi- or uni-potent differentiation potential, such that they are restricted in the lineages to which they can give rise. MSCs and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are commonly studied adult stem cells that can be derived from the bone marrow by sorting based on surface marker expression.33,34 The relative ease of isolation of adult stem and progenitor cells from somatic tissues facilitates the availability of such cell types and permits autologous transplantation. The limited potency of adult stem cells may simplify differentiation and produce a more homogeneous resulting population; however, primary cells can be difficult to obtain and/or impossible to expand for some lineages of interest, such as cardiac, hepatic, and neural cells. Additionally, within the same lineage, the resultant populations from adult and ESCs may differ, as cells derived from ESCs are believed to differentiate into more embryonic-like cells, and therefore possess more immature phenotypes, but potentially enhanced capacity for expansion and regeneration.20,35

Suspension cultures

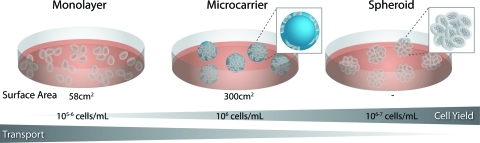

Monolayer culture of stem cells provides a defined substrate for cellular attachment and uniform application of external stimuli (Fig. 1). However, from a bioprocessing standpoint, monolayer culture is not readily amenable to the production of increased cellular yields necessary for regenerative therapies (upward of 109 cells, depending on the application).36–38 Although scalable adherent culture systems have been developed, these techniques rely on “scaling out” to provide more surface area for growth. In contrast to high density “scale up” techniques, which maintain cells in suspension, scalable monolayer cultures rely on relatively large volumes of media and cytokines, and therefore do not significantly reduce the cost required to maintain the cultures. Adhesion of stem cells to spherical microcarriers increases the surface area available for culture (approximately fivefold) without dramatically altering the exposure to nutrients or waste removal. However, microcarriers rely on stem cell adhesion to exogenous materials, which may alter differentiation.39,40 Culture of stem cells as 3D aggregates is thought to more accurately recapitulate cellular adhesions and signaling exhibited by stem cells found in native tissues.41,42 Microtissues have been created by the spontaneous aggregation of various cell types, resulting in homotypic and heterotypic spheroids, which retain aspects of metabolic, functional, and mechanical properties of living tissues.43–47 Neural stem cells (NSCs) are commonly cultured in suspension format as spheroids, referred to as neurospheres. ESCs are often differentiated in the form of cellular aggregates, termed embryoid bodies (EBs), which parallel many of the phenotypic changes that accompany gastrulation during embryogenesis in vivo,48 including the epithelial–mesenchymal transition, which is coordinately regulated by the balance of interactions between cells and ECM molecules.49 Taken together, stem cells can be cultured in a variety of formats and at a range of scales, from adherent monolayers to microcarriers to cellular aggregates in suspension; however, there is an inherent tradeoff between the transport of soluble factors and the scalability of the culture.

FIG. 1.

Stem cell differentiation formats. Stem cells can be cultured in monolayer or in suspension, either adherent to spherical microcarriers or as aggregates of cells. Suspension cultures generally increase the density of cells, and thus increase the overall cell yield per volume or media. Although suspension cultures are more scalable, the three-dimensional aggregate structure increases the diffusive distance between the media and cells at the center, which may result in decreased transport and the development of gradients of nutrients and metabolites throughout the spheroid. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/teb

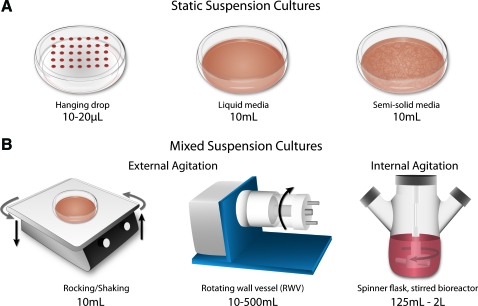

Several techniques have been developed to facilitate stem cell spheroid formation and differentiation, including methods that physically separate individual aggregates, which yield homogeneous populations, and batch methods that result in larger yields of EBs but with increased heterogeneity (Fig. 2A). Spheroid formation is especially prevalent in ESC culture because ESCs express E-cadherin during pluripotency and early differentiation, thus enabling the cells to readily, spontaneously aggregate on substrates or in suspension.50,51 Hanging drop cultures are initiated by suspending small volumes of culture media (10–20 μL) containing a defined number of cells (200–1000 cells) from the lid of a Petri dish. Although hanging drops yield uniformly-sized aggregates, the need to physically separate individual drops limits the number of spheroids formed per dish (∼100 per 10-cm plate); thus, hanging drops are not readily amenable to scale-up methods.52–54 It is also traditionally difficult to exchange media in the hanging drop format, though this has recently been accomplished through a modified 384-well hanging drop plate, which contains access ports for manipulation of the media in individual drops.55 Alternatively, static suspension culture is often accomplished by inoculating cells (103–106 cells) in a 35–100 mm Petri dish, in order to promote formation of spheroids via random aggregation of cells.56–58 Static suspension cultures, however, are often subject to agglomeration of individual spheroids, resulting in large cell masses, which are widely variable in size and shape, and thereby contribute to the overall heterogeneity of differentiation that is commonly observed.

FIG. 2.

Methods of embryoid body formation and propagation. (A) Aggregates of stem cells can be formed and maintained statically by physically separating cells in small volume drops or by spontaneous aggregation of cells within bulk suspension cultures in liquid or semi-solid media. (B) Dynamic cultures are amenable to supporting increased culture volumes (101–3 L) for the production of large cell yields in various formats, such as rotating wall vessels, or stirred bioreactors, which employ external or internal agitation, respectively. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/teb

Hydrodynamics in large-volume culture systems

Although suspension cultures are amenable to the culture of spheroids statically in bench-scale (<10 mL) volumes, translational approaches are increasingly moving toward larger scale culture systems (>100 mL), in which fluid mixing is introduced to reduce nutrient gradients and promote enhanced gas exchange within the culture volume.59 Mixing is accomplished either via external agitation of the entire vessel, as in rotating wall vessels, such as the slow turning lateral vessel and high aspect rotating vessel, or by internal agitation of an impeller, as in stirred flasks and pitched-blade bioreactors (Fig. 2B).60,61 The mixing within reactors introduces hydrodynamic conditions, which can generate high shear stresses depending on the rotation speed and vessel design. Quantifying the hydrodynamic environments within bioreactors and bioprocessing systems has been accomplished by combinations of computational fluid dynamic simulations and experimental particle-image velocimetry measurements.62,63 Such analyses aid in defining hydrodynamic properties, including shear stress and velocity profiles as well as frequency characteristics of the mixing system. Overall, results from such analyses indicate that fluid shear varies as a function of spatial position within the vessel, as well as rotational speeds and fluid viscosity.62,64,65 Shear computations for spinner flasks with centrally located constructs indicate that a maximum shear stress of 2.83 dyn/cm2 is imparted on cells within the scaffolds; however, this value is expected to increase near the walls of the bioreactor, and under increased mixing speeds, which may impart high shear stresses on cells in suspension.66 In contrast to larger volume systems (0.5–2 L), rocking/shaking suspension cultures are externally agitated lab-scale (10 mL) systems, with similar shear ranges (<2.5 dyn/cm2), and are amenable to screening multiple hydrodynamic conditions and additional variables in parallel.65,67,68 The complex shear environments created within 3D fluid mixing systems have motivated the need to better understand the impact of hydrodynamic parameters on cell responses (i.e., aggregation, metabolism, and phenotypes) in mixed culture conditions.

Hydrodynamic Culture of Stem Cells

The impact of hydrodynamics on stem cells manifests via alterations in several key cellular processes, including aggregation (kinetics, size), metabolism (viability, transport, proliferation), and phenotype (differentiation, function) (Table 1). Since all of these processes are inter-related within the context of stem cell biology, the cellular responses cannot easily be attributed to any one single parameter. Therefore, stem cell fate within a mixed fluid system is a result of the synergy between direct and indirect responses imparted by hydrodynamic environmental cues (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparison of Mixed Cultures to Static Suspension

| Parameter altered | Outcome | Cell type(s) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spheroid size | Decreased | mESC | 65 |

| Spheroid homogeneity | Increased | mESC, hESC | 65,67,75,84 |

| Aggregation kinetics | Accelerated | mESC | 67,71 |

| Spheroid yield | Increased | hESC | 72,75 |

| Cell expansion | Increased | hESC, mESC, PB MNC, HSC | 67,75,86,96–100,125 |

| Cell viability | Increased viability; decreased apoptosis; decreased necrosis | hESC, mESC | 67,72 |

| LDH | Increased (early); decreased (late) | hESC | 72 |

| Metabolism | Increased glucose consumption, lactic acid production, decreased pH | hESC | 72 |

| Differentiation potential | Comparable | hESC, mESC | 65,72,76,86 |

| Lineage-specific differentiation propensity | Altered in various cell types | hESC, mESC, MSC | 65,68,86,121,123,125 |

mESC, murine embryonic stem cell; hESC, human embryonic stem cell; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PB MNC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

Table 2.

Impact of Hydrodynamic Properties on Cell Spheroids

| Physical properties | Parameter altered | Outcome | Cell type(s) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vessel size and shape | Spheroid yield | Increased in STLV compared to HARV; increased in rocked compared to rotated | hESC, hepatocytes | 72,73 |

| Aggregation kinetics | Accelerated in wavy-wall compared to baffled, spinner flasks; accelerated in rocked compared to rotated | hepatocytes, chondrocytes | 59,73 | |

| Apoptosis | Increased in STLV compared to other systems | hESC | 86 | |

| Cell expansion | Increased compared to other systems (type and agitator); comparable when bioreactors scaled volumetrically | hESC, NSC | 89,125 | |

| Differentiation potential | Comparable in different systems | mESC, hESC | 86,124 | |

| Contractility | Increase in GBI spinner compared to erlenmeyer | hESC | 86 | |

| Agitator type and geometry | Cell viability | Decreased with paddle compared to ball impeller | primary brain cells | 85 |

| Cell expansion | Decreased with stir bar compared to flat blade impeller | PB MNC | 97 | |

| Agitation rate | Spheroid size | Decreased at higher agitation rates | primary brain cells, mESC, NSC | 65,67,76,85,88–90 |

| Spheroid yield | Increased at higher agitation rates | mESC | 90 | |

| Aggregation kinetics | Accelerated at decreased agitation rates | mESC | 65 | |

| Cell viability | Decreased at lower agitation rates | NSC | 89 | |

| Released LDH | Increased at higher agitation rates | mESC | 90 | |

| Differentiation potential | Comparable at a range of agitation rates | mESC | 65 | |

| Inoculation density | Cell expansion | Increased at higher inoculation densities (up to a max) | mESC | 84 |

| Differentiation kinetics | Delayed at higher inoculation densities | mESC | 84 | |

| Inoculation type | Cell expansion | Accelerated with pre-formed spheroid inoculation; increased overall with single cell inoculation | NSC | 57 |

| Media viscosity | Spheroid size | Increased with increasing viscosity | BHK | 87 |

| Aggregation kinetics | Accelerated with increasing viscosity | BHK | 87 |

BHK, baby hampster kidney cell; STLV, slow turning lateral vessel; HARV, high aspect rotating vessel; NSC, neural stem cell.

Hydrodynamic effect on aggregation

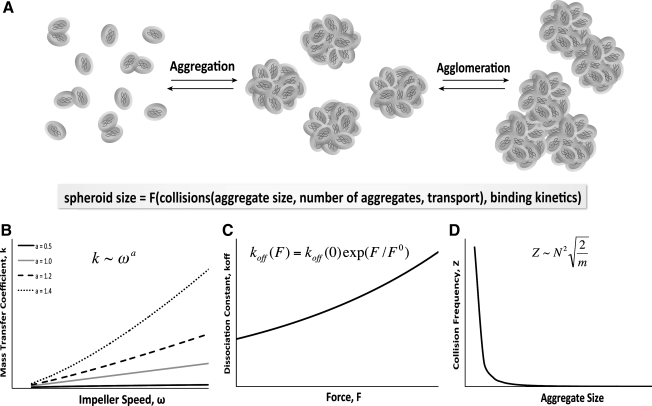

Mixed culture systems have been used for a long time as a means to facilitate multicellular aggregate formation, whereby a population of single cells self-assembles via cell–cell adhesion receptors (Fig. 3A). As mentioned previously, ESCs aggregate spontaneously in suspension culture via homophilic binding of the cell surface adhesion molecule E-cadherin that is expressed ubiquitously by undifferentiated ESCs. Several other types of stem cells, including NSCs and even MSCs, exhibit a similar propensity to form multicellular aggregates under appropriate conditions via other cell adhesion molecules; however, the molecular variations governing the mechanisms of cellular aggregation may result in altered binding kinetics of different stem cells populations. Therefore, this section discusses the aggregation kinetics within stirred culture systems in the context of EB formation via E-cadherin interactions; however, the principles highlighted can be generally applied to understanding the aggregation of various types of stem cell populations.

FIG. 3.

Stem cell aggregate formation. (A) Stem cells may form small aggregates or large agglomerates in suspension, with resulting spheroid size being influenced by hydrodynamic properties. Spheroid size is mediated by the number of collisions between cells in solution, which is impacted by (B) the transport parameters of the system (mass transfer coefficient, k, which increases as a power law of impeller speed, with the exponent (a), being a function of geometrical properties of the bioreactor system), as well as the (C) collision frequency, which is modulated by the mass (m) and number (N) of cells and aggregates in suspension. Additionally, final spheroid size is altered by (D) the binding kinetics (koff) of the adhesion molecules, such as integrins and cadherins, which changes as a function of forces exerted on the bonds.

Mixing within bioreactors has been extensively utilized, modeled, and validated within the field of chemical engineering and in the bioprocessing industry in particular. Therefore, it is well established that convective forces imparted through hydrodynamic mixing increase the mass transfer of the system. One by-product of enhanced mass transfer is more frequent collisions between particles, such as cells, suspended in the fluid. In general, the mass transfer coefficient increases as a power function of the impeller speed (Fig. 3B), and is subject to several parameters specific to the geometrical and physical characteristics of a bioreactor system.69,70 The increased transport in mixed bioreactors is correlated with increased spheroid formation efficiency and cellular incorporation in stirred suspension and rotary orbital suspension compared to static culture.67,71 The vessel size and shape also alter the aggregation dynamics, as indicated by modulation of spheroid formation rate within mixed various culture formats under similar agitation speeds.72,73 In addition to the hydrodynamic parameters, the cellular inoculation density also impacts the frequency of cell collisions in suspension; hence, understanding the changes in transport based on various parameters of the system (mixing, inoculation density) is important for rational design of systems to control stem cell aggregation.

The kinetics of receptor–ligand binding between cells can also be altered as a result of varying convective forces. Previous studies have measured the dissociation constant of homophilic E-cadherin binding to be 0.45/s, which corresponds to a bond duration of approximately 2 s; this bond duration is similar to the transient bonds established between selectins during leukocyte rolling, indicating that the individual E-cadherin bonds can be readily broken.74 Additionally, the dissociation constant exhibits behavior characteristic of the Bell model for kinetics of receptor ligand binding, resulting in an exponential increase as a function of force (Fig. 3C). Therefore, the shear forces imparted by hydrodynamics can manipulate the kinetics of E-cadherin interactions (or other cell adhesion molecules) in the context of cell aggregation. For example, the altered flow environment within the wavy-walled bioreactor supports increased chondrocyte aggregation compared to standard spinner flasks of comparable dimensions.59 Similarly, EB formation kinetics are altered at various rotary orbital speeds, with increased rotary speeds delaying, or even inhibiting, EB formation.65,75,76 However, the dissociation kinetics may also change as a function of the aggregation state of the cells, because multivalent E-cadherin interactions likely stabilize intercellular adhesion, and may withstand increased hydrodynamic forces. Taken together, these studies suggest that the increased transport and shear introduced by hydrodynamic culture environments can differentially regulate cellular spheroid formation through alterations in cell–cell collisions and adhesion binding kinetics at the cellular and molecular level, respectively.

The cell–cell adhesions established during EB formation are critical to differentiation and morphogenesis; however, a fine balance exists between the aggregation necessary for initial spheroid formation and agglomeration of individual spheroids. Excessive agglomeration typically results in large, necrotic regions located centrally within multicellular aggregates, as is commonly observed in static suspension cultures of EBs. Encapsulation methods have been used successfully as a means to culture ESCs and MSCs in mixed hydrodynamic bioreactors without agglomeration.77–81 Although encapsulation of ESCs within nonadherent hydrogels prevents agglomeration initially, as EBs grow in size they can protrude beyond the edges of agarose or alginate beads and begin to agglomerate.82,83 As spheroids merge due to agglomeration, the mass of individual spheroids increases, and the total concentration of spheroids in suspension decreases, leading to an overall decrease in the collision frequency between multicellular aggregates (Fig. 3D). The total surface area available for interaction between spheroids in culture also decreases, which may alter binding kinetics. The kinetics of spheroid agglomeration, however, may also be complicated by remodeling of cell adhesions as morphological events proceed, including changes in cadherin expression profiles, formation of adherens and tight junctions between cells, and heterophilic interactions with components of the ECM. Since collision frequency and binding kinetics are both altered by hydrodynamic parameters, spheroid size in mixed suspension cultures can be significantly impacted by agglomeration. Stirred suspension cultures maintained over a range of hydrodynamic conditions often exhibit decreased agglomeration compared to static suspension, resulting more homogeneous populations of mESCs and hESCs.65,67,75,84 Alteration of the hydrodynamic environment by employing different impeller types or changing media viscosity also alters the homogeneity and size of spheroids.85–87 in general, an inverse relationship exists between agitation speed and spheroid size, as evidenced by work in stem and progenitor cells from different species cultured in various types of stirred and mixed bioreactors.65,85,88–90

The aforementioned results indicate that various parameters of the hydrodynamic environment, including the configuration of the culture vessels and mixing conditions, may alter the transport and binding characteristics of stem cells, ultimately impacting the terminal size of spheroids. The control of spheroid size within hydrodynamic environments is a fine balance between promoting initial multicellular aggregate formation while limiting secondary spheroid agglomeration.

Hydrodynamic effects on metabolism

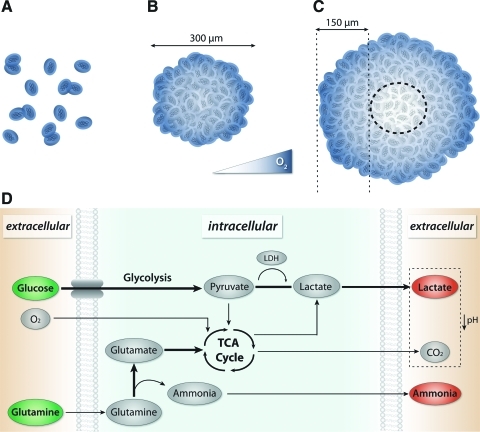

Physiochemical properties of the culture environment that promote the highly proliferative state of stem cells have been established based on known cellular requirements and parameters from in vivo conditions (Fig. 4). For example, the high metabolic demand required for proliferation of stem cells usually necessitates culture in media containing high concentrations of glucose (25 mM). When oxygen is readily available, glucose is metabolized by conversion of pyruvate into ATP through the tricarboxylic acid cycle, whereas in low oxygen conditions, pyruvate is converted to lactate by the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) during anaerobic glycolysis. Oxygen uptake rates for mammalian cells range from approximately 0.05–0.5 μmol/106 cells/h,91 with hematopoietic cells from the bone marrow exhibiting some of the lowest rates (as low as 0.005 μmol/106 cells/h).92 Recent studies indicate a link between the oxidative metabolic state and self-renewal in adult and ESC populations93,94; highly proliferative cells exhibit increased glycolysis and decreased oxygen consumption, similar to the Warburg effect in cancer cells.95 The mixing within large volume bioreactors and bioprocessing systems aids in the transport of nutrients and metabolites, and thereby enables sampling, monitoring, and control of the environment. HSCs are a useful model for understanding the impact of convective transport on expansion, because the culture of HSCs as single cells in suspension avoids the diffusive transport limitations in spheroids (Fig. 4A). Computational modeling of nutrient and oxygen transport supports experimentally observed increases in hematopoietic cell expansion within mixed cultures compared to static suspensions.96–100 Additionally, the number of cells inoculated within bioreactors impacts hematopoietic cell metabolism, with a minimum lower limit (∼2×105 cells/mL) required to facilitate expansion.97

FIG. 4.

Macro- and microscale changes in transport and stem cell metabolism. (A) Macro-scale transport in various stem cell culture formats. Blue intensity represents relative concentrations of soluble morphogens and nutrients (such as O2) within populations of single cells and (B, C) different-sized aggregates of stem cells. Concentration gradients arise in spheroid culture, with diffusive limitations in large aggregates. (D) Alteration of metabolic pathways in dynamic hESC culture leads to decreases (green) and increases (red) in local concentrations of nutrients and metabolites, respectively; the increased uptake of glucose and glutamine and excretion of lactate and ammonia lead to a highly proliferative state favoring expansion and decreases the pH of the extracellular environment. TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/teb

In contrast to single-cell suspensions, such as for HSCs, cells maintained as aggregates in culture confound metabolic analyses because gradients develop within the 3D structures (Fig. 4B, C). Ultimately the heterogeneous distribution of oxygen and nutrients within spheroids impact cell expansion and the doubling time of stem and progenitor cells.101 For example, inoculation of spinner flasks with pre-formed spheroids of NSCs resulted in faster cell expansion, whereas a single cell NSC suspension produced a larger overall expansion, indicating that metabolic differences may be linked to spheroid size and formation kinetics.57 In purely diffusive culture conditions, necrosis occurs in spheroids larger than approximately 300 μm in diameter,88 presumably due to O2 transport limitations, which indicates that the maximum diffusive distance is on the order of approximately 100–150 μm; however, in bioreactors, metabolic gradients are influenced by the transport properties (diffusive and convective) of mixing conditions. Hollow fiber capillary membrane bioreactors are a promising technology for decreasing diffusive distances approximately 10-fold, by providing media perfusion via many parallel sources distributed evenly throughout the culture.102 Additionally, inherent diffusional barriers of the spheroids may arise as a function of differentiation state; after several days in culture, EBs develop an exterior epithelial cell layer that limits diffusion of soluble factors, indicating that transport may be altered as a function of differentiation state.103,104

The impact of shear and transport within cell aggregates can be indirectly monitored through changes in the metabolic profile, specifically through extracellular LDH levels, indicative of cell lysis. Mixing conditions may be detrimental during early aggregation, as indicated by elevated LDH during early culture periods compared to static cultures; however, static cultures exhibit comparatively increased LDH at later stages of differentiation, likely due to cell death.72 mESCs in rotary orbital suspension demonstrate increased viability compared to static culture, with a decreased instance of necrotic core formation, likely due to a combination of decreased EB size (limited agglomeration) and increased convective transport of nutrients to the center of EBs.67 Spheroid cultures also exhibit a cumulative increase in released LDH (50–150 U/mL)72 compared to microcarrier cultures (<5 U/mL),105 indicating cell death as a result of differences in transport and shear forces between the different culture formats.

Monitoring of the physiochemical environment indicates that comparable ranges of nutrients and metabolites are maintained within suspension cultures of spheroids and in standard monolayer cultures.99 Additionally, comparable levels of glucose (1.94–1.23 g/L; 125 mL vs. 500 mL bioreactors after 20 days in culture), lactate (0.81–1.30 g/L), glutamine (1.21–1.13 mM), and ammonia (1.00–1.07 mM) are maintained when mixed NSC cultures are scaled from 125 to 500 mL bioreactors.89 Studies suggest, however, that the hydrodynamic environment within several mixed culture formats, including rotary, roller ball, and spinner flasks, supports increased hESC stem cell proliferation compared to static suspension cultures.75,76,86 Additionally, hESCs adherent to microcarriers in mixed cultures with mouse embryonic fibroblast conditioned media exhibited modulation of the metabolic state, including high glucose and glutamine consumption, increased ammonia and lactate production, and acidification of the media (Fig. 4D); however, the metabolic state may also be altered depending on specific media formulations.106 Glutamine supplementation may be a limiting factor for adipose stem cell expansion within batch cultures maintained over 150 h, because the cells also exhibit decreased proliferation in the absence of glutamine107; removal of the amino acid from culture media results in cells entering a quiescent-like state with decreased metabolic requirements, including reduced glucose consumption. Additionally, the accumulation of metabolites, specifically lactate and ammonia, which can create unfavorable culture conditions, such as decreased pH, may be a factor leading to decreased cell viability, and therefore limiting total cell expansion.76 Correlation of the physiochemical signature of the culture environment with phenotypic indicators may permit indirect real-time analysis of the differentiation state of stem cells by monitoring secreted metabolic factors.98 In particular, due to the heterogeneous proliferative and differentiation states of stem cells, increased control of metabolites may be important for the development of more efficient expansion and directed differentiation protocols. For example, monitoring of bioreactor conditions and constant media exchange via perfusion are important modifications, which may enable the automation and standardization of culture conditions.102,108–110 Mixed culture conditions that support stem cell expansion and differentiation, therefore, require a complex balance between providing sufficient concentrations of nutrients and limiting accumulation of toxic metabolic by-products, while also taking into account the potential effects of fluid mixing on cell lysis.

Hydrodynamic effects on phenotype

As noted previously, stem cell phenotype is exquisitely sensitive to a variety of environmental cues, many of which can be modulated within mixed culture environments. Due to the heterogeneous nature of differentiation within stem cell spheroids and the complex hydrodynamic environment, it can be difficult to ascertain which parameters directly and indirectly impact cell phenotype.

Mixed bioreactors and bioprocessing systems have been utilized as high yield configurations for expansion and differentiation of stem cell populations. For example, in the presence of appropriate environmental conditions (leukemia inhibitory factor supplementation or conditioned media), mESCs and hESCs expanded as aggregates or on microcarriers within mixed bioreactors can be maintained in a pluripotent, undifferentiated state.76,105,111–115 Several groups have also demonstrated that stem cell differentiation potential is not altered within bioreactor systems of varying volumetric scale, agitated either externally or internally; MSCs,116 NSCs,89,117,118 and ESCs67,72,75,119 retain the capacity to differentiate into their respective cell lineages, although some studies indicate lower efficiency of differentiation.120 Compared to static suspension cultures, the endogenous propensity of some ESC lines to differentiate toward particular lineages does not seem to be altered over a range of hydrodynamic conditions. For example, Fok and Zandstra observed no statistical difference in cardiac or hematopoietic differentiation between EBs cultured in spinner flasks (60 and 100 rpm) compared to EBs differentiated in static cultures119; similarly, there was no difference in cardiomyocyte differentiation between static mEBs and those cultured within slow turning lateral vessels.71

However, studies indicate changes in global gene expression profiles within differentiating MSC and ESC spheroids maintained in hydrodynamic culture conditions compared to static conditions,65,121,122 suggesting discrepancies in the tendency of dynamically cultured stem cells to differentiate toward particular lineages. The propensity for MSCs to differentiate along adipogenic lineages is increased when cultured in mixed vessels.121,123 Additionally, MSCs exhibit enhanced osteogenic differentiation when MSCs are cultured dynamically as aggregates121; however, evidence also supports decreased osteogenic differentiation of MSCs on microcarriers.123 The difference in MSC phenotype may, however, be explained by culture on microcarriers compared to as aggregates; the properties of exogenous substrates may alter differentiation, as matrix elasticity can modulate stem cell phenotype, with stiffer matrices promoting osteogenic differentiation.39,40 Within aggregates of ESCs, the bioreactor type impacts the hematopoietic differentiation profile, with an increased Sca-1+ population derived from cultures in rotating wall vessels, compared to increases in C-kit+ cells maintained in spinner flasks.124 Additionally, others have illustrated enhanced cardiomyocyte differentiation in spinner flasks compared to static conditions,125 as well as within rotary orbital suspension culture.68 The agitation speeds in various systems also modulate ESC phenotype,65 as EBs maintained at a range of rotary orbital speeds exhibit temporal modulation of gene expression indicative of changes in differentiation among the three different germ lineages.

As noted previously, mixing speeds can modulate spheroid aggregation kinetics and spheroid size, with slower speeds leading to larger spheroids, which form more quickly than at slower speeds. The noted differences in cardiomyocyte differentiation, therefore, may result from changes in the metabolic environment, as a result of decreased transport within larger aggregates compared to smaller spheroids.126 Several groups have linked hypoxic conditioning to increased hematopoietic and cardiogenic differentiation.101,108,125,127 Similarly, metabolites in the environment, including lactate, alter MSC gene expression128 and drive angiogenic response in macrophages.129 Changes in bioreactor configurations that alter the metabolic environment may be more or less conducive to certain cell phenotypes, thus promoting or inhibiting differentiation to specific cell phenotypes. Additionally, cell organization is also central to morphogenesis and differentiation through the expression of lineage-specific cell adhesion molecules, such as E-cadherin. Binding and remodeling of adhesion receptors can alter differentiation through the activation of downstream signaling pathways such as the Wnt/β-catenin pathway,50,51 thus highlighting the importance of the temporal aspect of cell aggregation and the implications for altering downstream signaling kinetics. Altered phenotype based on aggregation kinetics and spheroid size has been established through research on the enrichment of mesoderm and cardiogenic phenotypes when aggregates are formed using hanging drop culture.54,56,68,130 As is discussed throughout this article, cell aggregation, metabolism, and phenotype are all interconnected within the context of stem cell biology, which underscores the importance of developing methods for decoupling these variables, in order to understand the impact of environmental conditions on stem cell spheroids.

Future Opportunities

The complexities of hydrodynamic culture environments drive the need to systematically examine individual parameters since elucidating direct, indirect, and synergistic effects will enable more rational design of bioreactors and bioprocessing systems. For example, simultaneous alterations in spheroid size and differentiation of ESCs within mixed culture systems highlight the importance of separating independent variables to understand the direct influence of hydrodynamic forces. Several groups have recently developed methods for controlling ESC colony and stem cell spheroid sizes131–135 as well as aggregate shapes (i.e., rods, tori, honeycombs, rectangles, annuli, and sinusoidal bands),136–139 using microprinting and microwell technologies to physically separate cells in high-throughput formats. These advances have enabled the analysis of stem cell differentiation as a function of aggregate shape138 and size,132,140 and have noted increased cardiogenic differentiation within EBs of approximately 400 μm diameter.125,134 Changes in cardiogenic differentiation due to spheroid size have been correlated to non-canonical signaling of the Wnt pathway through altered expression of Wnt5a and Wnt11134; however, the specific mechanism for this regulation remains largely unknown. Additionally, the technologies for producing size-controlled EBs may also enable analysis of the influence of hydrodynamics, independent of spheroid size. These studies may, however, only be amenable for a certain range of hydrodynamic conditions, due to the potential for individually formed spheroids to agglomerate in suspension. Additionally, formation of spheroids before hydrodynamic culture alters both spheroid size and formation kinetics. Ultimately, development of culture methods to independently control spheroid size and formation kinetics will be important for controlling stem cell expansion and differentiation.

Changes in differentiation due to spheroid size may also be a result of altered transport profiles within both diffusive and convective environments. Within mixed bioreactors, modulation of the hydrodynamic environment changes both transport and fluid shear; development of methods to decouple these variables may elucidate governing parameters within these cultures. For example, modeling of convective transport within various mixed culture systems may elucidate changes in metabolic parameters as a result of spheroid size. Additionally, methods for eliminating gradients of nutrients within the interior of spheroids will likely result in more homogeneous directed differentiation of stem cell aggregates. Microspheres have been incorporated within stem cell aggregates, enabling delivery of morphogens more homogeneously throughout the multicellular microenvironment.104,141–145 The combination of the hydrodynamic culture environment with microsphere-mediated delivery may enable analysis of the impact of fluid shear on cell spheroids, independent of small molecule and growth factor transport limitations. Additionally, combinatorial methods for simultaneously controlling morphogen delivery and the hydrodynamic environment could lead to synergistic methods to more efficiently and effectively direct stem cell differentiation.

The modulation of stem cell aggregation, metabolism, and phenotype by mixed cultures has implications for bioprocessing and bioreactor design for future applications in stem cell therapies. Bench-scale systems (100–1 mL) such as rotary orbital culture may be useful to examine the effects of hydrodynamic conditions on stem cell formation, morphology, and differentiation because, using smaller volume cultures, multiple parameters can be systematically probed in parallel in a rapid manner. Defining the governing properties within hydrodynamic culture systems that regulate differentiation will aid in the development of efficient bioprocessing protocols and bioreactor design. This goal necessitates detailed analysis of the hydrodynamic parameters within various bioreactor formats, under different mixing configurations and speeds. Several formats currently exploit the inherent scalability of suspension cultures, to employ large volume mixed systems (102–3 mL), enabling the increased production of differentiating cells required for large-scale drug screening or the potential therapeutic application of stem-cell-derived products. Large-scale stirred culture systems are advantageous because they are amenable to numerous parallel modifications, which provide media perfusion and dialysis, enable automated maintenance of appropriate metabolic conditions, and decrease physiochemical fluctuations, which occur during manual feeding by bulk media exchange.89,90,108,117,125,146,147 Ultimately, defining the governing hydrodynamic parameters for altering aggregation, metabolism, and phenotype, as well as synergies between the interdependent variables will enable engineering of bioreactor and bioprocessing systems for controlled, scalable, and efficient expansion and differentiation of stem cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors are supported by funding from the NIH (EB010061). M.A.K. is currently supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, and C.Y.S. was supported by an American Heart Association Pre-Doctoral Fellowship.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Baraniak P.R. McDevitt T.C. Stem cell paracrine actions and tissue regeneration. Regen Med. 2010;5:121. doi: 10.2217/rme.09.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNeish J. Embryonic stem cells in drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:70. doi: 10.1038/nrd1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hove J.R. Köster R.W. Forouhar A.S. Acevedo-Bolton G. Fraser S.E. Gharib M. Intracardiac fluid forces are an essential epigenetic factor for embryonic cardiogenesis. Nature. 2003;421:172. doi: 10.1038/nature01282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hogers B. DeRuiter M.C. Gittenberger-de Groot A.C. Poelmann R.E. Unilateral vitelline vein ligation alters intracardiac blood flow patterns and morphogenesis in the chick embryo. Circ Res. 1997;80:473. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groenendijk B.C. Hierck B.P. Vrolijk J. Baiker M. Pourquie M.J. Gittenberger-de Groot A.C., et al. Changes in shear stress-related gene expression after experimentally altered venous return in the chicken embryo. Circ Res. 2005;96:1291. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000171901.40952.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malek A.M. Alper S.L. Izumo S. Hemodynamic shear stress and its role in atherosclerosis. JAMA. 1999;282:2035. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.21.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies P.F. Flow-mediated endothelial mechanotransduction. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:519. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levesque M.J. Nerem R.M. The elongation and orientation of cultured endothelial cells in response to shear stress. J Biomech Eng. 1985;107:341. doi: 10.1115/1.3138567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franke R.P. Gräfe M. Schnittler H. Seiffge D. Mittermayer C. Drenckhahn D. Induction of human vascular endothelial stress fibres by fluid shear stress. Nature. 1984;307:648. doi: 10.1038/307648a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Topper J.N. Cai J. Falb D. Gimbrone M.A. Identification of vascular endothelial genes differentially responsive to fluid mechanical stimuli: cyclooxygenase-2, manganese superoxide dismutase, and endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase are selectively up-regulated by steady laminar shear stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:10417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsao P.S. Buitrago R. Chan J.R. Cooke J.P. Fluid flow inhibits endothelial adhesiveness. Nitric oxide and transcriptional regulation of vcam-1. Circulation. 1996;94:1682. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.7.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies P.F. Remuzzi A. Gordon E.J. Dewey C.F. Gimbrone M.A. Turbulent fluid shear stress induces vascular endothelial cell turnover in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:2114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.7.2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamamoto K. Takahashi T. Asahara T. Ohura N. Sokabe T. Kamiya A., et al. Proliferation, differentiation, and tube formation by endothelial progenitor cells in response to shear stress. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:2081. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00232.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang H. Riha G.M. Yan S. Li M. Chai H. Yang H., et al. Shear stress induces endothelial differentiation from a murine embryonic mesenchymal progenitor cell line. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1817. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000175840.90510.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamamoto K. Sokabe T. Watabe T. Miyazono K. Yamashita J.K. Obi S., et al. Fluid shear stress induces differentiation of Flk-1-positive embryonic stem cells into vascular endothelial cells in vitro. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1915. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00956.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adamo L. Naveiras O. Wenzel P.L. McKinney-Freeman S. Mack P.J. Gracia-Sancho J., et al. Biomechanical forces promote embryonic haematopoiesis. Nature. 2009;459:1131. doi: 10.1038/nature08073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahsan T. Nerem R.M. Fluid shear stress promotes an endothelial-like phenotype during the early differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:3547. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin G.R. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:7634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans M.J. Kaufman M.H. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doetschman T. Eistetter H. Katz M. Schmidt W. Kemler R. The in vitro development of blastocyst-derived embryonic stem cell lines: formation of visceral yolk sac, blood islands and myocardium. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1985;87:27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomson J.A. Kalishman J. Golos T.G. Durning M. Harris C.P. Becker R.A., et al. Isolation of a primate embryonic stem cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomson J.A. Kalishman J. Golos T.G. Durning M. Harris C.P. Hearn J.P. Pluripotent cell lines derived from common marmoset (callithrix jacchus) blastocysts. Biol Reprod. 1996;55:254. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod55.2.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reubinoff B.E. Pera M.F. Fong C.Y. Trounson A. Bongso A. Embryonic stem cell lines from human blastocysts: somatic differentiation in vitro. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:399. doi: 10.1038/74447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomson J.A. Itskovitz-Eldor J. Shapiro S.S. Waknitz M.A. Swiergiel J.J. Marshall V.S., et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato N. Sanjuan I.M. Heke M. Uchida M. Naef F. Brivanlou A.H. Molecular signature of human embryonic stem cells and its comparison with the mouse. Dev Biol. 2003;260:404. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ginis I. Luo Y. Miura T. Thies S. Brandenberger R. Gerecht-Nir S., et al. Differences between human and mouse embryonic stem cells. Dev Biol. 2004;269:360. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi K. Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi K. Tanabe K. Ohnuki M. Narita M. Ichisaka T. Tomoda K., et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu J. Vodyanik M.A. Smuga-Otto K. Antosiewicz-Bourget J. Frane J.L. Tian S., et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wernig M. Meissner A. Foreman R. Brambrink T. Ku M. Hochedlinger K., et al. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448:318. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chin M.H. Mason M.J. Xie W. Volinia S. Singer M. Peterson C., et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells and embryonic stem cells are distinguished by gene expression signatures. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:111. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doi A. Park I.H. Wen B. Murakami P. Aryee M.J. Irizarry R., et al. Differential methylation of tissue- and cancer-specific CpG island shores distinguishes human induced pluripotent stem cells, embryonic stem cells and fibroblasts. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1350. doi: 10.1038/ng.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pittenger M.F. Mackay A.M. Beck S.C. Jaiswal R.K. Douglas R. Mosca J.D., et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spangrude G.J. Heimfeld S. Weissman I.L. Purification and characterization of mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 1988;241:58. doi: 10.1126/science.2898810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Longaker M.T. Whitby D.J. Ferguson M.W. Lorenz H.P. Harrison M.R. Adzick N.S. Adult skin wounds in the fetal environment heal with scar formation. Ann Surg. 1994;219:65. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199401000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lock L.T. Tzanakakis E.S. Stem/progenitor cell sources of insulin-producing cells for the treatment of diabetes. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:1399. doi: 10.1089/ten.2007.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jing D. Parikh A. Canty J.M. Tzanakakis E.S. Stem cells for heart cell therapies. Tissue Eng Part B. 2008;14:393. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tzanakakis E.S. Hess D.J. Sielaff T.D. Hu W.S. Extracorporeal tissue engineered liver-assist devices. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2000;2:607. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.2.1.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Engler A.J. Sen S. Sweeney H.L. Discher D.E. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Engler A.J. Carag-Krieger C. Johnson C.P. Raab M. Tang H.Y. Speicher D.W., et al. Embryonic cardiomyocytes beat best on a matrix with heart-like elasticity: scar-like rigidity inhibits beating. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3794. doi: 10.1242/jcs.029678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akins R.E. Rockwood D. Robinson K.G. Sandusky D. Rabolt J. Pizarro C. Three-dimensional culture alters primary cardiac cell phenotype. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:629. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang T.T. Hughes-Fulford M. Monolayer and spheroid culture of human liver hepatocellular carcinoma cell line cells demonstrate distinct global gene expression patterns and functional phenotypes. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:559. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fukuda J. Sakai Y. Nakazawa K. Novel hepatocyte culture system developed using microfabrication and collagen/polyethylene glycol microcontact printing. Biomaterials. 2006;27:1061. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelm J.M. Ehler E. Nielsen L.K. Schlatter S. Perriard J.C. Fussenegger M. Design of artificial myocardial microtissues. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:201. doi: 10.1089/107632704322791853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kunz-Schughart L.A. Schroeder J.A. Wondrak M. van Rey F. Lehle K. Hofstaedter F., et al. Potential of fibroblasts to regulate the formation of three-dimensional vessel-like structures from endothelial cells in vitro. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1385. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00248.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelm J.M. Ittner L.M. Born W. Djonov V. Fussenegger M. Self-assembly of sensory neurons into ganglia-like microtissues. J Biotechnol. 2006;121:86. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kelm J.M. Fussenegger M. Microscale tissue engineering using gravity-enforced cell assembly. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:195. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murry C.E. Keller G. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells to clinically relevant populations: lessons from embryonic development. Cell. 2008;132:661. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shukla S. Nair R. Rolle M.W. Braun K.R. Chan C.K. Johnson P.Y., et al. Synthesis and organization of hyaluronan and versican by embryonic stem cells undergoing embryoid body differentiation. J Histochem Cytochem. 2010;58:345. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.954826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dasgupta A. Hughey R. Lancin P. Larue L. Moghe P.V. E-cadherin synergistically induces hepatospecific phenotype and maturation of embryonic stem cells in conjunction with hepatotrophic factors. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;92:257. doi: 10.1002/bit.20676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Larue L. Antos C. Butz S. Huber O. Delmas V. Dominis M., et al. A role for cadherins in tissue formation. Development. 1996;122:3185. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maltsev V.A. Wobus A.M. Rohwedel J. Bader M. Hescheler J. Cardiomyocytes differentiated in vitro from embryonic stem cells developmentally express cardiac-specific genes and ionic currents. Circ Res. 1994;75:233. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wiese C. Kania G. Rolletschek A. Blyszczuk P. Wobus A.M. Pluripotency: capacity for in vitro differentiation of undifferentiated embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;325:181. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-005-7:181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoon B.S. Yoo S.J. Lee J.E. You S. Lee H.T. Yoon H.S. Enhanced differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into cardiomyocytes by combining hanging drop culture and 5-azacytidine treatment. Differentiation. 2006;74:149. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tung Y.C. Hsiao A.Y. Allen S.G. Torisawa Y.S. Ho M. Takayama S. High-throughput 3D spheroid culture and drug testing using a 384 hanging drop array. Analyst. 2011;136:473. doi: 10.1039/c0an00609b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kurosawa H. Methods for inducing embryoid body formation: in vitro differentiation system of embryonic stem cells. J Biosci Bioeng. 2007;103:389. doi: 10.1263/jbb.103.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kallos M.S. Behie L.A. Inoculation and growth conditions for high-cell-density expansion of mammalian neural stem cells in suspension bioreactors. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;63:473. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19990520)63:4<473::aid-bit11>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Itskovitz-Eldor J. Schuldiner M. Karsenti D. Eden A. Yanuka O. Amit M., et al. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into embryoid bodies compromising the three embryonic germ layers. Mol Med. 2000;6:88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bueno E.M. Bilgen B. Carrier R.L. Barabino G.A. Increased rate of chondrocyte aggregation in a wavy-walled bioreactor. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;88:767. doi: 10.1002/bit.20261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schwarz R.P. Goodwin T.J. Wolf D.A. Cell culture for three-dimensional modeling in rotating-wall vessels: an application of simulated microgravity. J Tissue Cult Methods. 1992;14:51. doi: 10.1007/BF01404744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prewett T. Goodwin T. Spaulding G. Three-dimensional modeling of T-24 human bladder carcinoma cell line: a new simulated microgravity culture vessel. Methods Cell Sci. 1993;15:29. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bilgen B. Chang-Mateu I.M. Barabino G.A. Characterization of mixing in a novel wavy-walled bioreactor for tissue engineering. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;92:907. doi: 10.1002/bit.20667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Unger D. Muzzio F. Aunins J. Computational and experimental investigation of flow and fluid mixing in the roller bottle bioreactor. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2000;70:117. doi: 10.1002/1097-0290(20001020)70:2<117::aid-bit1>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bilgen B. Sucosky P. Neitzel G.P. Barabino G.A. Flow characterization of a wavy-walled bioreactor for cartilage tissue engineering. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006;95:1009. doi: 10.1002/bit.20775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sargent C.Y. Berguig G.Y. Kinney M.A. Hiatt L.A. Carpenedo R.L. Berson R.E., et al. Hydrodynamic modulation of embryonic stem cell differentiation by rotary orbital suspension culture. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;105:611. doi: 10.1002/bit.22578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sucosky P. Osorio D.F. Brown J.B. Neitzel G.P. Fluid mechanics of a spinner-flask bioreactor. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;85:34. doi: 10.1002/bit.10788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carpenedo R.L. Sargent C.Y. McDevitt T.C. Rotary suspension culture enhances the efficiency, yield, and homogeneity of embryoid body differentiation. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2224. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sargent C. Berguig G. McDevitt T. Cardiomyogenic differentiation of embryoid bodies is promoted by rotary orbital suspension culture. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:331. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Harnby N. Edwards M. Nienow A. Mixing in the Process Industries. 2nd. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fernando W.J.N. Othman M.R. Karunaratne D.G.G.P. Agitation speed and interfacial mass transfer coefficients in mass transfer dominated reactions. IJET. 2010;11:95. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang X. Wei G. Yu W. Zhao Y. Yu X. Ma X. Scalable producing embryoid bodies by rotary cell culture system and constructing engineered cardiac tissue with ES-derived cardiomyocytes in vitro. Biotechnol Prog. 2006;22:811. doi: 10.1021/bp060018z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gerecht-Nir S. Cohen S. Itskovitz-Eldor J. Bioreactor cultivation enhances the efficiency of human embryoid body (hEB) formation and differentiation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;86:493. doi: 10.1002/bit.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brophy C.M. Luebke-Wheeler J.L. Amiot B.P. Khan H. Remmel R.P. Rinaldo P., et al. Rat hepatocyte spheroids formed by rocked technique maintain differentiated hepatocyte gene expression and function. Hepatology. 2009;49:578. doi: 10.1002/hep.22674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Perret E. Benoliel A.M. Nassoy P. Pierres A. Delmas V. Thiery J.P., et al. Fast dissociation kinetics between individual E-cadherin fragments revealed by flow chamber analysis. EMBO J. 2002;21:2537. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cameron C.M. Hu W.-S. Kaufman D.S. Improved development of human embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies by stirred vessel cultivation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006;94:938. doi: 10.1002/bit.20919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cormier J.T. zur Nieden N.I. Rancourt D.E. Kallos M.S. Expansion of undifferentiated murine embryonic stem cells as aggregates in suspension culture bioreactors. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:3233. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rowley J.A. Madlambayan G. Mooney D.J. Alginate hydrogels as synthetic extracellular matrix materials. Biomaterials. 1999;20:45. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hwang Y.S. Cho J. Tay F. Heng JYY. Ho R. Kazarian S.G., et al. The use of murine embryonic stem cells, alginate encapsulation, and rotary microgravity bioreactor in bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2009;30:499. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Benoit DSW. Schwartz M.P. Durney A.R. Anseth K.S. Small functional groups for controlled differentiation of hydrogel-encapsulated human mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Mater. 2008;7:816. doi: 10.1038/nmat2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jing D. Parikh A. Tzanakakis E.S. Cardiac cell generation from encapsulated embryonic stem cells in static and scalable culture systems. Cell Transplant. 2010;19:1397. doi: 10.3727/096368910X513955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Randle W.L. Cha J.M. Hwang Y-S. Chan KLA. Kazarian S.G. Polak J.M., et al. Integrated 3-dimensional expansion and osteogenic differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:2957. doi: 10.1089/ten.2007.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dang S.M. Gerecht-Nir S. Chen J. Itskovitz-Eldor J. Zandstra P.W. Controlled, scalable embryonic stem cell differentiation culture. Stem Cells. 2004;22:275. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-3-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dang S.M. Zandstra P.W. Scalable production of embryonic stem cell-derived cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;290:353. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-838-2:353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zweigerdt R. Burg M. Willbold E. Abts H. Ruediger M. Generation of confluent cardiomyocyte monolayers derived from embryonic stem cells in suspension: a cell source for new therapies and screening strategies. Cytotherapy. 2003;5:399. doi: 10.1080/14653240310003062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Santos S.S. Leite S.B. Sonnewald U. Carrondo MJT. Alves P.M. Stirred vessel cultures of rat brain cells aggregates: characterization of major metabolic pathways and cell population dynamics. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:3386. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yirme G. Amit M. Laevsky I. Osenberg S. Itskovitz-Eldor J. Establishing a dynamic process for the formation, propagation, and differentiation of human embryoid bodies. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17:1227. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Moreira J.L. Santana P.C. Feliciano A.S. Cruz P.E. Racher A.J. Griffiths J.B., et al. Effect of viscosity upon hydrodynamically controlled natural aggregates of animal cells grown in stirred vessels. Biotechnol Prog. 1995;11:575. doi: 10.1021/bp00035a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sen A. Kallos M. Behie L. Effects of hydrodynamics on cultures of mammalian neural stem cell aggregates in suspension bioreactors. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2001;40:5350. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Baghbaderani B.A. Behie L.A. Sen A. Mukhida K. Hong M. Mendez I. Expansion of human neural precursor cells in large-scale bioreactors for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. Biotechnol Prog. 2008;24:859. doi: 10.1021/bp070324s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schroeder M. Niebruegge S. Werner A. Willbold E. Burg M. Ruediger M., et al. Differentiation and lineage selection of mouse embryonic stem cells in a stirred bench scale bioreactor with automated process control. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;92:920. doi: 10.1002/bit.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Miller W.M. Blanch H.W. Regulation of animal cell metabolism in bioreactors. Biotechnology. 1991;17:119. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-409-90123-8.50012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Peng C.A. Palsson B.O. Determination of specific oxygen uptake rates in human hematopoietic cultures and implications for bioreactor design. Ann Biomed Eng. 1996;24:373. doi: 10.1007/BF02660886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schieke S.M. Ma M. Cao L. McCoy J.P. Liu C. Hensel N.F., et al. Mitochondrial metabolism modulates differentiation and teratoma formation capacity in mouse embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802763200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mazumdar J. O'Brien W.T. Johnson R.S. LaManna J.C. Chavez J.C. Klein P.S., et al. O2 regulates stem cells through Wnt/β-catenin signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:1007. doi: 10.1038/ncb2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kondoh H. Lleonart M.E. Nakashima Y. Yokode M. Tanaka M. Bernard D., et al. A high glycolytic flux supports the proliferative potential of murine embryonic stem cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:293. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pathi P. Ma T. Locke B.R. Role of nutrient supply on cell growth in bioreactor design for tissue engineering of hematopoietic cells. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;89:743. doi: 10.1002/bit.20367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Collins P.C. Miller W.M. Papoutsakis E.T. Stirred culture of peripheral and cord blood hematopoietic cells offers advantages over traditional static systems for clinically relevant applications. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1998;59:534. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19980905)59:5<534::aid-bit2>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Collins P.C. Nielsen L.K. Patel S.D. Papoutsakis E.T. Miller W.M. Characterization of hematopoietic cell expansion, oxygen uptake, and glycolysis in a controlled, stirred-tank bioreactor system. Biotechnol Prog. 1998;14:466. doi: 10.1021/bp980032e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liu Y. Liu T. Fan X. Ma X. Cui Z. Ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic stem cells derived from umbilical cord blood in rotating wall vessel. J Biotechnol. 2006;124:592. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Li Q. Liu Q. Cai H. Tan W.S. A comparative gene-expression analysis of CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells grown in static and stirred culture systems. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2006;11:475. doi: 10.2478/s11658-006-0039-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gassmann M. Fandrey J. Bichet S. Wartenberg M. Marti H.H. Bauer C., et al. Oxygen supply and oxygen-dependent gene expression in differentiating embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:2867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gerlach J.C. Lübberstedt M. Edsbagge J. Ring A. Hout M. Baun M., et al. Interwoven four-compartment capillary membrane technology for three-dimensional perfusion with decentralized mass exchange to scale up embryonic stem cell culture. Cells Tissues Organs (Print) 2010;192:39. doi: 10.1159/000291014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sachlos E. Auguste D.T. Embryoid body morphology influences diffusive transport of inductive biochemicals: a strategy for stem cell differentiation. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4471. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Carpenedo R.L. Bratt-Leal A.M. Marklein R.A. Seaman S.A. Bowen N.J. McDonald J.F., et al. Homogeneous and organized differentiation within embryoid bodies induced by microsphere-mediated delivery of small molecules. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2507. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lock L.T. Tzanakakis E.S. Expansion and differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to endoderm progeny in a microcarrier stirred-suspension culture. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:2051. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen X. Chen A. Woo T.L. Choo ABH. Reuveny S. Oh SKW. Investigations into the metabolism of two-dimensional colony and suspended microcarrier cultures of human embryonic stem cells in serum-free media. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:1781. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Follmar K.E. Decroos F.C. Prichard H.L. Wang H.T. Erdmann D. Olbrich K.C. Effects of glutamine, glucose, and oxygen concentration on the metabolism and proliferation of rabbit adipose-derived stem cells. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:3525. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bauwens C. Yin T. Dang S. Peerani R. Zandstra P.W. Development of a perfusion fed bioreactor for embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte generation: oxygen-mediated enhancement of cardiomyocyte output. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;90:452. doi: 10.1002/bit.20445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Serra M. Brito C. Sousa MFQ. Jensen J. Tostões R. Clemente J., et al. Improving expansion of pluripotent human embryonic stem cells in perfused bioreactors through oxygen control. J Biotechnol. 2010;148:208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ma C. Kumar R. Xu X. Mantalaris A. A combined fluid dynamics, mass transport and cell growth model for a three-dimensional perfused biorector for tissue engineering of haematopoietic cells. Biochem Eng J. 2007;35:1. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kehoe D.E. Lock L.T. Parikh A. Tzanakakis E.S. Propagation of embryonic stem cells in stirred suspension without serum. Biotechnol Prog. 2008;24:1342. doi: 10.1002/btpr.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.zur Nieden N.I. Cormier J.T. Rancourt D.E. Kallos M.S. Embryonic stem cells remain highly pluripotent following long term expansion as aggregates in suspension bioreactors. J Biotechnol. 2007;129:421. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fernandes A.M. Fernandes T.G. Diogo M.M. da Silva C.L. Henrique D. Cabral JMS. Mouse embryonic stem cell expansion in a microcarrier-based stirred culture system. J Biotechnol. 2007;132:227. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Krawetz R. Taiani J. Liu S. Meng G. Li X. Kallos M., et al. Large-scale expansion of pluripotent human embryonic stem cells in stirred suspension bioreactors. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2010;16:573. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2009.0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Singh H. Mok P. Balakrishnan T. Rahmat S.N.B. Zweigerdt R. Up-scaling single cell-inoculated suspension culture of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 2010;4:165. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chen X. Xu H. Wan C. McCaigue M. Li G. Bioreactor expansion of human adult bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2052. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gilbertson J.A. Sen A. Behie L.A. Kallos M.S. Scaled-up production of mammalian neural precursor cell aggregates in computer-controlled suspension bioreactors. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006;94:783. doi: 10.1002/bit.20900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Serra M. Brito C. Costa E.M. Sousa M.F.Q. Alves P.M. Integrating human stem cell expansion and neuronal differentiation in bioreactors. BMC Biotechnol. 2009;9:82. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-9-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Fok E.Y. Zandstra P.W. Shear-controlled single-step mouse embryonic stem cell expansion and embryoid body-based differentiation. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1333. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Taiani J. Krawetz R.J. Nieden N.Z. Wu Y.E. Kallos M.S. Matyas J.R., et al. Reduced differentiation efficiency of murine embryonic stem cells in stirred suspension bioreactors. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:989. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Frith J. Thomson B. Genever P. Dynamic three-dimensional culture methods enhance mesenchymal stem cell properties and increase therapeutic potential. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2010;16:735. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2009.0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Liu H. Lin J. Roy K. Effect of 3D scaffold and dynamic culture condition on the global gene expression profile of mouse embryonic stem cells. Biomaterials. 2006;27:5978. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zayzafoon M. Gathings W.E. McDonald J.M. Modeled microgravity inhibits osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells and increases adipogenesis. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2421. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Fridley K.M. Fernandez I. Li M-T. Kettlewell R.B. Roy K. Unique differentiation profile of mouse embryonic stem cells in rotary and stirred tank bioreactors. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:3285. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Niebruegge S. Bauwens C.L. Peerani R. Thavandiran N. Masse S. Sevaptisidis E., et al. Generation of human embryonic stem cell-derived mesoderm and cardiac cells using size-specified aggregates in an oxygen-controlled bioreactor. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;102:493. doi: 10.1002/bit.22065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cameron C.M. Harding F. Hu W.S. Kaufman D.S. Activation of hypoxic response in human embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies. Exp Biol Med. 2008;233:1044. doi: 10.3181/0709-RM-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ramírez-Bergeron D.L. Runge A. Dahl KDC. Fehling H.J. Keller G. Simon M.C. Hypoxia affects mesoderm and enhances hemangioblast specification during early development. Development. 2004;131:4623. doi: 10.1242/dev.01310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zieker D. Schäfer R. Glatzle J. Nieselt K. Coerper S. Kluba T., et al. Lactate modulates gene expression in human mesenchymal stem cells. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:297. doi: 10.1007/s00423-008-0286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]