Abstract

Introduction:

HER-2 expression in prostate cancer is associated with a worse prognosis and is suggested to play a role in androgen resistance. We present a study of HER-2 expression in circulating tumor cells and micrometastasis in bone marrow and the effect of androgen blockage or DES in the presence of HER-2 expressing cells.

Patients and Methods:

A multicenter study of men with prostate cancer, treated with surgery, radiotherapy, or observation, and with or without hormone therapy. Mononuclear cells were separated from blood and bone marrow aspirate by differential centrifugation, touch preps were made from bone marrow biopsy samples. Prostate cells were detected using anti-PSA monoclonal antibody and standard immunocytochemistry. Positive samples were processed using Herceptest® to determine HER-2 expression. After 1 year, patients were re-evaluated and the findings of HER-2 expression and PSA change compared with treatment.

Results:

Total 199 men participated, and 97 had a second evaluation 1 year later, frequency of HER-2 expression in circulating tumor cells and micrometastasis was 18% and 21%, respectively. There was no significant difference in HER-2 expression in the pretreatment group, after radical surgery or radiotherapy or with biochemical failure. Men with androgen blockade had a significantly higher expression of HER-2 (58%) (P =0.001). Of the 97 men with a second evaluation, 56 were in the observation arm, 27 androgen blockade, and 14 DES. Use of androgen blockade or DES significantly reduced serum PSA levels in comparison with observation (P =0.001). However, there was a significant increase in HER-2 expression in patients with androgen blockade (P =0.05) en comparison with observation or DES treatment. No patient with observation or DES became HER-2 positive, en comparison 4/22 patients initially HER-2 negative became HER-2 positive with androgen blockade.

Conclusions:

The results suggest that HER-2 positive cells are resistant to androgen blockade. In an environment lacking androgens, HER-2 positive cells are selected and survive, while HER-2 negative cells are eliminated thus decreasing the serum PSA. The population of HER-2 positive cells proliferate producing androgen-independent disease. DES does not increase HER-2 expression possibly by stimulating beta-estrogen receptors and blocking HER-2 androgen receptor activation.

Keywords: Androgen blockade, circulating tumor cells, DES, HER-2, micrometastasis, prostate cancer

INTRODUCTION

Early-stage prostate cancer exhibits androgen dependence, and as a result of androgen blockade or withdrawal, prostate cancer cells undergo cell cycle arrest or apoptosis. The use of androgen blockage, medically or surgically, is the main form of therapy for men with metastatic disease or as adjuvant therapy in high-risk patients. Although most patients respond initially to therapy, these patients eventually relapse and die from their disease.[1] Once hormone refractory disease is present, the prognosis is very poor with a median survival of 9–12 months.[2] The mechanisms responsible for the initial survival and subsequent proliferation of androgen-resistant prostate cancer cells remain poorly characterized. Identification of patients who are likely to fail androgen blockage would be helpful for selecting patients best suited for other treatments or clinical trials of early systemic intervention.[3] Therefore, there is a clear need for novel biomarkers that are specifically associated with aggressive disease and treatment outcomes.

HER-2 is a member of the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases and plays a crucial role in growth, differentiation, and motility of normal and cancer cells. HER-2 has been proposed as a survival factor for prostate cells in the absence of androgens, possibly by activating the androgen receptor.[4–6]

The aim of this study was to detect prostate cells in blood and bone marrow of men with prostate cancer and to determine HER-2 protein expression in these cells using immunocytochemistry and in a subgroup of hormone naive patients, to determine changes in HER-2 expression after commencing androgen blockade or DES.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Men with prostate cancer and attending the National Geriatric Institute, the Hospital de Carabineros de Chile and Institute of Bio-Oncología, Santiago, Chile, between September 2007 and June 2009 were invited to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria were biopsy-proven prostate cancer, treated by radical prostatectomy, radiotherapy, or observation; men were subdivided according to secondary treatment; observation, androgen blockage, or DES.

After written informed consent was obtained, an 8 ml blood sample was taken using a 21G needle and collected into EDTA (Beckinson-Vacutainer®) for CPC detection. Each sample was coded with a serial number and the cytologist was blinded to patient and biopsy details.

Separation of mononuclear cells

The mononuclear cells were separated within 6 hours of obtaining the sample, using gel differential centrifugation (Histopaque 1.077, Sigma-Aldrich) according to manufacturer's instructions at room temperature. The cells were resuspended in 100 μl of autologous plasma and 25 μl aliquots of cell suspension used to prepare slides (sialinized DAKO. USA) then dried in air for 24 hours and fixed using a solution of 70% ethanol, 5% formaldehyde, and 25% phosphate buffered saline (PBS) pH7.4 (DAKO, USA) for 5 minutes and washed twice with PBS.

Immunocytochemistry

Slides were processed within 1 hour of fixation and incubated with anti-PSA clone 28A4 (Novocastra Laboratory, UK) in a concentration of 2.5 μg/ml for 1 hour at room temperature. Circulating prostate cells (CPCs) were identified by using an alkaline phosphatase (AP)–antialkaline phosphatase system (LSAB2, DAKO, USA) with neofuschin as the chromogen and levisamole as an endogenous AP inhibitor according to manufacturer's instructions. Identification of CPCs (PSA-positive cells) was according to the criteria of ISHAGE.[7]

Slides positive for PSA-immunostaining cells underwent a second stage of immunocytochemical staining using the HercepTest® according to manufacturer's instructions. Cells were classified as PSA positive and either HER-2 negative or positive and with the score 0-3+ regarding HER-2 staining intensity [Figures 1–7].

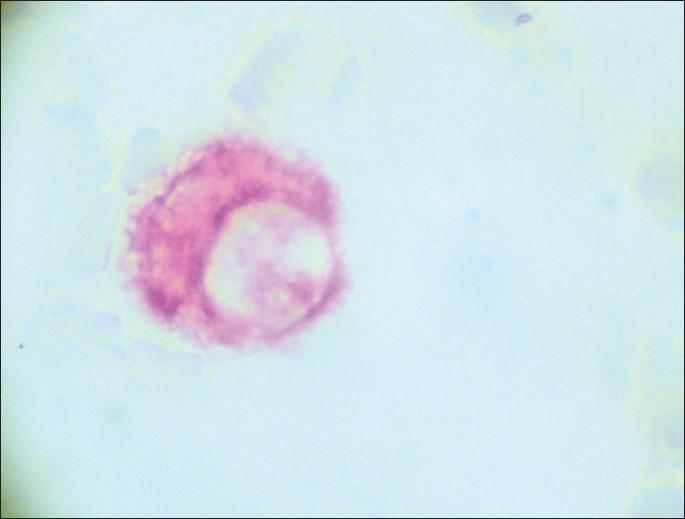

Figure 1.

CPC PSA (+) red HER-2 negative (×500).

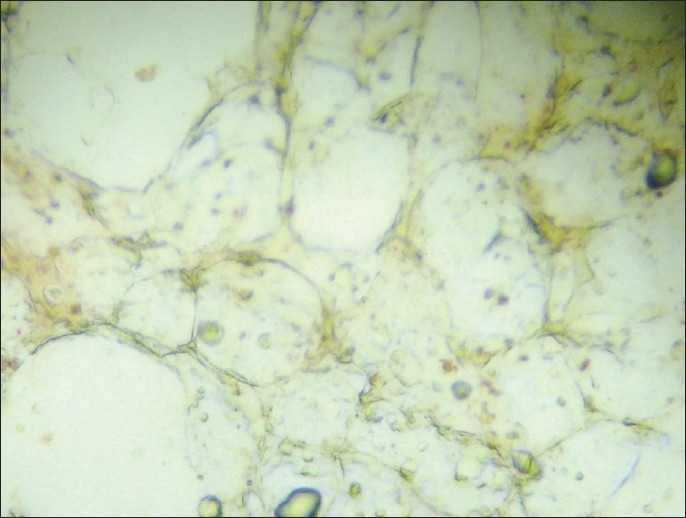

Figure 7.

Leucocito PSA (–) HER-2 (–) (×500).

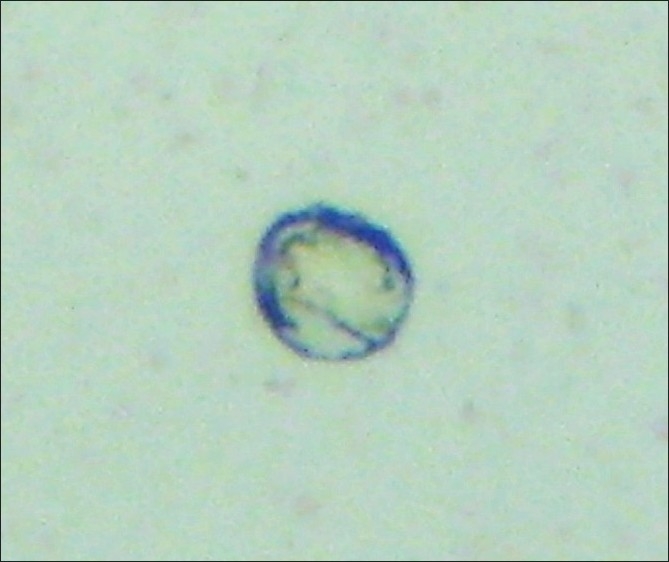

Figure 2.

CPC PSA (+) red HER-2 (+) black (×500).

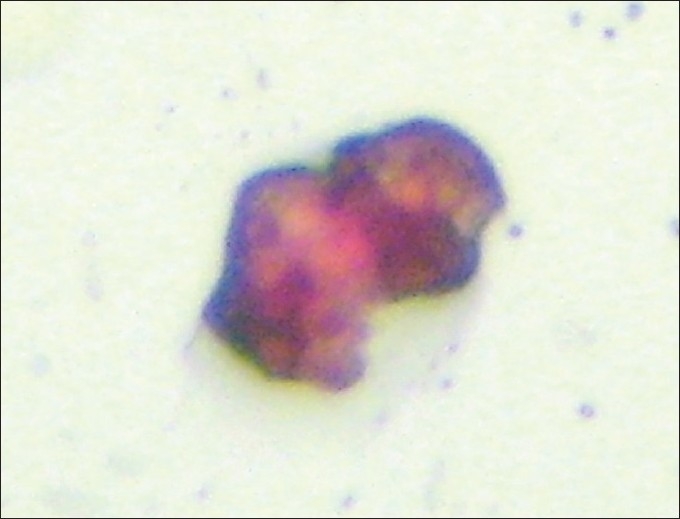

Figure 3.

Micrometastasis (–) (×100).

Figure 4.

Micrometastasis PSA (+) (red) HER-2 negative (×100).

Figure 5.

Micrometastasis PSA (+) red HER-2 (+) black (×200).

Figure 6.

Micrometastasis PSA (+) red HER-2 (+) black (×100).

Patients underwent bone marrow biopsy and aspiration from the posterior superior iliac crest, under sedation with midazolam and local anesthesia. The biopsy sample was used to prepare three touch preps and fixed and immunostained as earlier described. A micrometastasis was defined as microfragments with PSA-staining cells.[8] Four milliliter bone marrow aspirate samples were collected in EDTA (Vacutainer® -Beckinson) and processed as described for blood samples.

HER-2-positive patients were defined according to the criteria of Osman et al.[5] as 2+ and 3+ staining in more than 10% of PSA-positive cells. The mean HER-2 expression in all patients was calculated by using the formula; sum of HER-2 expression in PSA-expressing cells divided by the total number of PSA-expressing cells.

The patients were divided into four groups: group 1 – patients without treatment, observation, or awaiting primary therapy; group 2 – patients after primary therapy but without biochemical failure, defined as a serum PSA < 0, 2 ng/ml postprostatectomy radical or a rise of ≥2.0 ng/ml from the nadir PSA (defined as the lowest achieved) postradiotherapy according to the definition of the Phoenix Group of 2006 and revised by ASTRO[9] and without hormone-therapy; group 3 – patients after primary therapy with biochemical failure and without hormone-therapy; group 4 – patients with hormone therapy.

Ninety-seven patients had a second evaluation of blood and bone marrow 1 year later. These patients had the mean HER-2 value calculated; the changes in HER-2 positivity, in HER-2 value, and serum PSA were registered.

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were considered significant at P < 0.05. Continuous variables with a normal distribution were described using the mean and standard deviation, while continuous asymmetrical, categorical, and ordinal variables were described using frequencies, the median, and interquartile values.

Comparisons between groups were analyzed for multiple comparisons, using the Scheffe test for continuous variables with a normal distribution and the Kruksal–Wallis Test for continuous variables with a non-normal distribution. Logistic regression was used to analyze binominal variables and the Poisson regression for continuous variables.

Ethical considerations

The study was performed in complete agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethics committee.

RESULTS

Initial results of all patients

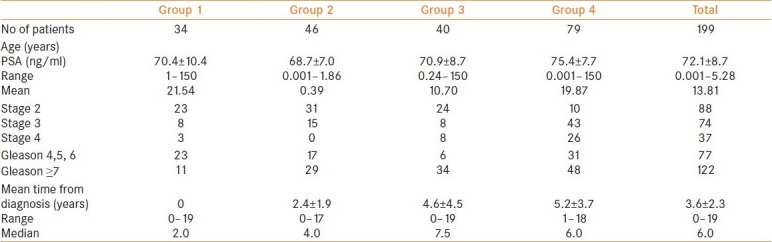

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of 199 men with a mean age of 72.1±8.7 years that fulfilled inclusion criteria for these studies.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical details of patients

Age

There was a significant difference in the age of the different groups (Scheffe test of variance P=0.0001). Comparing groups, the men in groups 1 and 2 were significantly younger than the men in group 4 (P=0.037 and P=0.001, respectively, Scheffe test for variance). This was to be expected; with the disease progression from pretreatment to androgen blockade there is a time factor.

Time from diagnosis to sample

One-way analysis of variance (Kruskal–Wallis) showed a significant difference from the time from diagnosis to the sample being taken (Chi squared 3 d.f. P=0.0001). The mean time between the diagnosis of prostate cancer and the sample being taken was significantly shorter between groups 1 and 2–4 (P=0.0011, P=0.0001, and P=0.0001, respectively, ranks mean difference). There was no difference between groups 2 and 3 (P=0.23 Ranks Mean Difference) or between groups 3 and 4 (P=0.35, ranks mean difference) but there was a difference between groups 2 and 4 (P=0.003, ranks mean difference).

Frequency of HER-2 expression in CPCs and micrometastasis

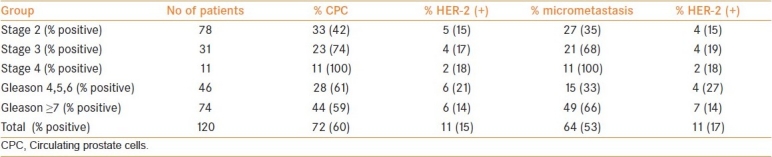

In groups 1–3, the frequency of CPCs HER-2-positive patients was 17%, 15%, and 22%, respectively, and in the micrometastasis 19%, 15%, and 29%, respectively. There were no significant differences in the frequency of HER-2 expression between groups 1–3 (men without systemic therapy), or between the expression of HER-2 in CPCs and micrometastasis in the same patient (Fisher two-tailed P=0.745 and P=0.112, respectively). These groups were, therefore, combined of all men without systemic therapy [Table 2].

Table 2.

Frequency of CPCs and micrometastasis and HER-2 expression in men without hormonal therapy

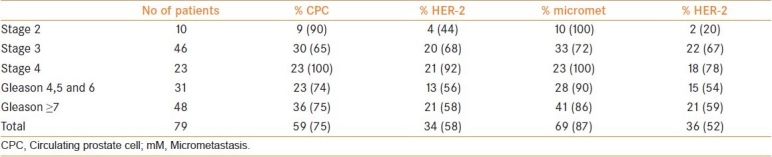

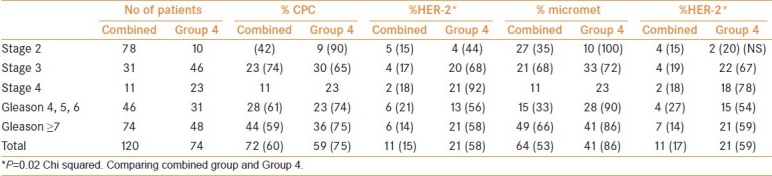

Men in group 4 had a higher frequency of HER-2 expression [Table 3](Chi squared P=0.001) than groups 1–3 and the combined group both for CPCs and for micrometastasis; 56% versus 13% and 53% versus 17%, respectively [Table 4]. There was no significant difference in the frequency of HER-2 expression between men receiving DES therapy (4/13) to those without systemic therapy (9/66) (Chi squared P=0.21). However, men receiving DES had a lower frequency of HER-2 expression in CPCs than those receiving androgen blockade (4/13 vs 29/45, respectively) (Chi squared P=0.03) and in micrometastasis (4/15 vs 36/54) (Chi squared P=0.02).

Table 3.

Frequency of CPCs and micrometastasis and HER-2 expression in Group 4

Table 4.

Comparison between the combined group and Group 4

In men HER-2 positive, there was no difference in the mean HER-2 expression per cell in those with or without systemic treatment (P=0.66 Kruskal–Wallis).

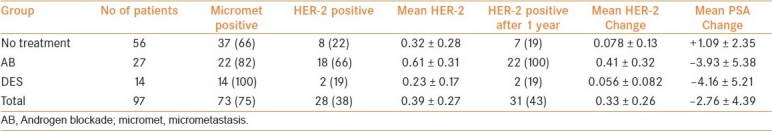

Differences with time [Table 5].

Table 5.

Changes in HER-2 expression with treatment

A total of 97 men had a second evaluation 12 months later, 56 continued with no treatment in the observation group (n=23) or after radical treatment (n=33), 27 continued with androgen blockade with flutamide and/or leuprolein, and 14 continued with DES.

Age

The mean age for each group was 72±9.8 years observation group, 75.8±8.6 years androgen blockage group, and 78.5±8.5 years DES group. The only significant difference was that men with DES were significantly older than men with no treatment after radical therapy (P=0.004 Kukalis–Wallis).

PSA initial value and change with time

Men in observation had a lower initial PSA than the men with androgen blockade or DES treatment. The mean change in the serum PSA showed no significant differences between the use of androgen blockage and DES (P=0.17, Rank mean difference); the mean PSA change was significantly higher in the androgen blockade group and DES group in comparison with the no treatment (P=0.001 and P=0.001, respectively, Rank mean difference).

Initial HER-2 status and change in positivity

The initial HER-2 positivity of the three groups were observation 10/58, androgen blockade 11/26, and DES 4/13; the androgen blockade group had a significantly higher frequency of HER-2-positive patients than the observation (P=0.001 Kruskal–Wallis) and DES (P=0.001 Kruskal–Wallis) groups. After 1 year of therapy, there was a significant difference in the frequency of HER-2-positive patients between the observation and androgen blockade groups (P=0.017 ordered logistic regression) but no difference between observation and DES groups (P=0.275 ordered logistic regression). At the end of 1 year, no patient in the observation group or DES group changed from HER-2 negative to positive, whereas in the androgen blockade group eight patients became HER-2 positive (P=0.001 and P=0.001, Chi squared).

Change in HER-2 score

The change in the value of the HER-2 score over 1 year was 0.078±0.13 in the observation group, 0.41±0.33 in the androgen blockade group, and 0.056±0.082 in the DES group. There was a significant difference in the change in HER-2 score between the observation and androgen blockade groups (P=0.02 Kruksal–Wallis) and between DES and androgen blockade groups (P=0.03 Kruksal–Wallis), but no difference between DES and observation groups (P=0.16 Kruksal–Wallis).

DISCUSSION

The differences in age and serum PSA levels between groups are consistent with the treated history of prostate cancer. That group 4 had a higher Gleason score probably reflects the higher probability of biochemical failure and therefore hormonal therapy. In groups 1 and 2, CPC detection frequency was not associated with Gleason but micrometastasis detection was, suggesting that cancer cell dissemination is independent of Gleason score in contrast to bone marrow implantation. The higher frequency of CPCs in group 3 reflects higher disease activity and the higher number of circulating tumor cells in group 1 reflects a higher tumor burden.

HER-2 expression

There are studies linking the expression of HER-2 in prostate cancer to disease progression and the development of androgen-independent disease. This study shows that in hormone-naive patients, whether in patients undergoing observation, or post-treatment with or without biochemical failure, the expression of HER-2 was infrequent both in CPCs and micrometastasis (17%) and is similar to that found by the authors[5] in prostate biopsies. Patients treated with androgen blockage had a significantly increased level of HER-2 expression in both CPCs (58%) and micrometastasis (62%). These results are similar to 67% of cases HER-2 positive found by Osman et al.[5] in prostate biopsies after neoadjuvant androgen blockage. However, the frequency of HER-2 expression in patients treated with DES was similar to hormone-naive patients.

That HER-2 expression was not significantly different between the groups of hormone-naive patients suggests that changes in HER-2 expression are not time dependent and not part of the natural progression of prostate cancer progression. That men with biochemical failure and those with androgen blockade had a similar time from diagnosis suggests that androgen blockage causes the increased expression of HER-2.

During follow-up, in patients treated with androgen blockage, serum PSA decreased but the mean HER-2 score significantly increased as did the number of patients becoming HER-2 positive. This suggests two possible explanations: firstly HER-2-positive cells are resistant to androgen blockade and selected in an androgen-depleted environment, while HER-2-negative cells undergo apoptosis and die. This finding is coherent with HER-2 activation of the androgen receptor in the absence of androgens. It does not exclude the possibility that androgen ablation upregulates HER-2 expression in cells which express HER-2 at low levels. However, experiments with Dunning R-3327 prostate cancer cells in rats showed no adaption of HER-2-negative cells to become positive, but that the original tumor is a mixture of HER-2-positive and negative cells.[10]

This has clinical implications. Pantel et al.[11] have shown that after neoadjuvant androgen blockade, 16/21 (76%) patients become negative for bone marrow micrometastasis, while a further 4/21 (19%) had decreased numbers of cells detected. Kollerman et al.[12] later demonstrated that patients positive for bone marrow micrometastasis after neoadjuvant androgen blockade had a worse prognosis. These clinical results are consistent with our findings in the men reevaluated after 1 year; androgen blockade decreases serum PSA but in HER-2-positive disease does not completely eliminate the micrometastasis. These surviving HER-2-positive cells would be able to grow and result in a decreased PSA progression free survival as described by Kollerman et al.[12]

Effect of DES

DES decreased serum PSA without an increase in HER-2 expression suggesting that its mode of action is different. It is widely considered that DES exerts its control via the hypothalamus, decreasing the release of LHRH, FSH, and testosterone to castration levels, inhibiting adrenal gland testosterone synthesis and decreasing serum levels of dihydroepiandrosterone.[13] However, if this was the only mechanism then one would expect HER-2 cells to be selected. One possible explication is the activation of the beta-estrogen receptor, its expression being bimodal, low in localized prostate cancer, and increased in metastasis.[14] It is postulated that the activation of this receptor inhibits prostate growth, and only cells that express this receptor are susceptible to estrogen or antiestrogen therapy.[15] That DES decreased serum PSA levels is consistent with its known effect; that HER-2 expression did not change suggests that its mode of action equally affects HER-2-positive and negative cells, suggesting a mechanism of action downstream of that of HER-2. Therefore cells expressing HER-2 would not have a survival advantage in an androgen-depleted environment. This would explain why there is a clinical and biochemical response in patients who relapse while taking androgen blockade.

The possible clinical utility of the use of HER-2 expression is the identification of patients resistant to androgen blockade. The results are consistent with those of Okegawa et al. where pretreatment HER-2 levels was a negative prognostic factor in patients about to undergo hormonal therapy for metastatic prostate cancer.[16] The use of DES as monotherapy or as part of a combination and/or sequential therapy in these patients could be a clinical option that warrants further investigation. The use of bicalutamide may be an alternative in these patients, as studies have shown that it may have a use in HER-2-positive patients.[17] Studies in vitro with cells lines have demonstrated the importance of specific anti-HER-2 agents trastuzumab[18] and pertuzumab.[19] However, clinical studies have failed to show such a benefit of monotherapy[20] possibly because of the cell mixture of (HER-2-positive and negative cells). Thus prospective trails of specific anti-HER-2 therapy should be in combination with other therapeutic agents based on the HER-2 status of CPCs and/or micrometastasis.

That there were no significant differences between the expression of HER-2 in CPCs and micrometastasis suggests that the use of CPC technology could be useful in the sense that repeated blood samples are less invasive than repeated bone marrow sampling. However, the number of cells detected is much lower. The present study emphasizes the importance of characterizing the clinical state of the patient, especially the detailed information of prior hormone exposure. The expression of HER-2 initially and the changes in its expression after treatment could be clinically useful in the selection and monitoring of therapy, both with neoadjuvant therapy and after biochemical failure in order to prevent and/or delay the selection of androgen-independent clones. This is essential when designing clinical trials targeting HER-2.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Hospital de Carabineros de Chile Research Fund. Thanks to Roche Laboratory, Chile, and in particular Mr. Rodrigo López for the donation of the HercepTest. Mr. Lopez or Roche Laboratory did not participate in the experimental design or conclusions of this study. There were no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klein LA. Prostatic carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;300:26–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197904123001504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yagoda A, Petrylak D. Cytotoxic chemotherapy for advanced hormone resistant prostate cancer. Cancer. 1993;71:1098–109. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930201)71:3+<1098::aid-cncr2820711432>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Debes JD, Tindall DJ. Mechanisms of androgen refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1488–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Signoretti S, Montironi R, Manola J, Altimari A, Tam C, Bubley G, et al. Her-2(neu) expression and progression toward androgen independence in human prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1918–25. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.23.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osman I, Scher HI, Drobnjak M, Verbel D, Morris M, Agus D, et al. HER-2/neu (p185neu) protein expression in the natural or treated history of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2643–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craft N, Shostak Y, Carey M, Sawyers CL. A mechanism for hormone independent prostate cancer through modulation of androgen receptor signaling by the HER-2/neu tyrosine kinase. Nat Med. 1999;3:280–5. doi: 10.1038/6495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borgen E, Naume B, Nesland JM. Standardization of the immunocytochemical detection of cancer cells in BM and blood: Establishment of objective criteria for the evaluation of immunostained cells. Cytotherapy. 1999;5:377–88. doi: 10.1080/0032472031000141283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray NP, Calaf GM, Badinez L. Presence of prostate cells in bone marrow biopsies as a sign of micrometastasis in cancer patients. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:571–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roach M, 3rd, Hanks G, Thames H., Jr Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: Recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:965–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isaacs JT. Adaptation versus selection as the mechanism responsible for the relapse of prostate cancer to androgen ablation therapy as studied in the Dunning R- 3327-H adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 1982;42:5010–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pantel K, Enzmann T, Kollermann J, Caprano J, Reithmuller G, Kollerman MW. Immunocytochemical monitoring of micrometastatic disease reduction of prostate 11. cancer cells in bone marrow by androgen deprivation. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:521–5. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970516)71:4<521::aid-ijc4>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kollermann J, Weikert S, Schostak M, Kempkensteffen C, Klienschmidt K, Rau T, et al. Prognostic significance of disseminated tumor cells in the bone marrow of prostate cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant hormone treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4928–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malkowitz SB. The role of diethylstilbestrol in the treatment of prostate cancer. Urology. 2001;58:108–13. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leav I, Lau KM, Adams JY, McNeal JE, Taplin ME, Wang J, et al. Comparative studies of the estrogen receptors alpha and beta and the androgen receptor in normal human prostate glands, dysplasia and in primary and metastatic carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:79–92. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61676-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horvath LG, Henshall SM, Lee CS, Head DR, Quinn DI, Mekela S, et al. Frequent loss of estrogen receptor beta expression in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5331–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okegawa T, Kinlo M, Nutahara K, Higashihara E. Pretreatment serum level of HER2/neu as a prognostic factor in metastatic prostate cancer patients about to undergo endocrine therapy. Int J Urol. 2006;13:1197–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gravina GL, Festuccia C, Millimaggi D, Tombolini V, Dolo V, Vicentini C, et al. Bicalutamide demonstrates biologic effectiveness in prostate cancer cell lines and tumor primary cultures irreapective of HER2/neu expression levels. Urology. 2009;74:452–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agus DB, Scher HI, Higgins B, Fox WD, Heller G, Fazzari M, et al. Response of prostate cancer to anti-HER-2/neu antibody in androgen dependent and independent human xenograft models. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4761–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agus DB, Sweeney CJ, Morris MJ, Mendelson DS, McNeel DG, Ahmann FR, et al. Efficacy and safety of singl agent pertuzumab (rhuMAb 2C4), a human epidermal growth factor receptor dimerization inhibitor, in castration resistant prostate cancer after progression from taxane based therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:675–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ziada A, Barqawi A, Glode LM, Varella-Garcia M, Crighton F, Majeski S, et al. The use of trastuzumab in the treatment of hormone refractory prostate cancer; phase II trial. Prostate. 2004;60:332–7. doi: 10.1002/pros.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]