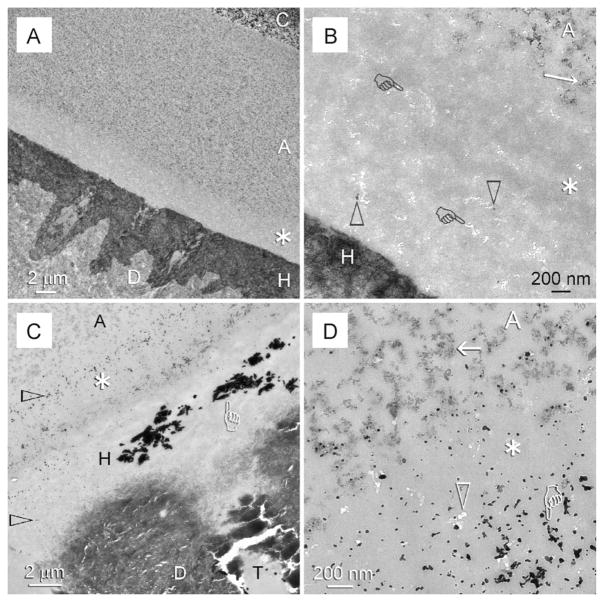

Fig. 3.

TEM of specimens from the chlorhexidine group that were retrieved after 12 months of intraoral function. C: composite; A: filled adhesive; D: dentine. (A) Stained demineralised specimen with an intact hybrid layer (H). Although chlorhexidine prevented degradation of the collagen component of the hybrid layer, water entrapment within the resin–dentine interface resulted in a nanofiller-depleted zone (asterisk) within the basal portion of the adhesive. (B) High magnification of the nanofiller-depleted zone in (A). Nanofillers (open arrowheads) were almost completely dissolved, leaving behind clusters of nanovoids (pointers) within the adhesive resin matrix. By contract, nanofiller clusters (arrow) were readily observed within the top part of the adhesive (A). (C) An unstained, non-demineralised specimen from the same group showing silver-filled, water-rich regions (pointer) within the intact hybrid layer (H). Additional silver grains (open arrowheads) could be seen within the hybrid layer and the nanofiller-depleted zone of the adhesive (asterisk). T: dentinal tubule. (D) High magnification of (C) showing silver deposits (pointer) in nanovoids (open arrowhead) of the nanofiller-depleted zone (asterisk) of the adhesive (A). Intact nanofiller clusters (arrow) could be seen within the adhesive that was further away from the hybrid layer and dentinal tubules, where they were less susceptible to water hydrolysis during in vivo ageing.