Abstract

The defining functional feature of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors is activation gating, the energetic coupling of ligand binding into opening of the associated ion channel pore. NMDA receptors are obligate heterotetramers typically composed of glycine-binding GluN1 and glutamate-binding GluN2 subunits that gate in a concerted fashion, requiring all four ligands to bind for subsequent opening of the channel pore. In an individual subunit, the extracellular ligand-binding domain, composed of discontinuous polypeptide segments S1 and S2, and the transmembrane channel–forming domain, composed of M1–M4 segments, are connected by three linkers: S1–M1, M3–S2, and S2–M4. To study subunit-specific events during pore opening in NMDA receptors, we impaired activation gating via intrasubunit disulfide bonds connecting the M3–S2 and S2–M4 in either the GluN1 or GluN2A subunit, thereby interfering with the movement of the M3 segment, the major pore-lining and channel-gating element. NMDA receptors with gating impairments in either the GluN1 or GluN2A subunit were dramatically resistant to channel opening, but when they did open, they showed only a single-conductance level indistinguishable from wild type. Importantly, the late gating steps comprising pore opening to its main long-duration open state were equivalently affected regardless of which subunit was constrained. Thus, the NMDA receptor ion channel undergoes a pore-opening mechanism in which the intrasubunit conformational dynamics at the level of the ligand-binding/transmembrane domain (TMD) linkers are tightly coupled across the four subunits. Our results further indicate that conformational freedom of the linkers between the ligand-binding and TMDs is critical to the activation gating process.

INTRODUCTION

Representative crystal structures of ligand-gated ion channels from multiple families are now available (Jiang et al., 2002; Hilf and Dutzler, 2008; Kawate et al., 2009; Sobolevsky et al., 2009). Nevertheless, the dynamics of their activation gating—the series of conformational changes that couple the binding of ligands to the opening of the ion channel pore—remain unresolved. Ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs), including the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subtype, mediate fast excitatory synaptic transmission integral to central nervous system function. Kinetic studies of NMDA receptors have identified key energetic steps, including various intermediate states, in the activation gating process (Wyllie et al., 1996; Banke and Traynelis, 2003; Auerbach and Zhou, 2005; Schorge et al., 2005; Dravid et al., 2008; Kussius and Popescu, 2009). These kinetic mechanisms therefore provide a template to define the dynamics of gating in NMDA receptors, although the structural events underlying the kinetic steps are unknown.

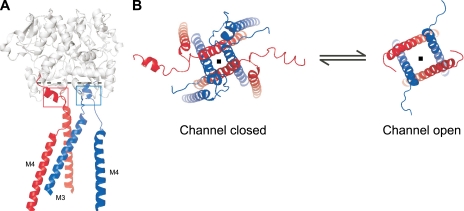

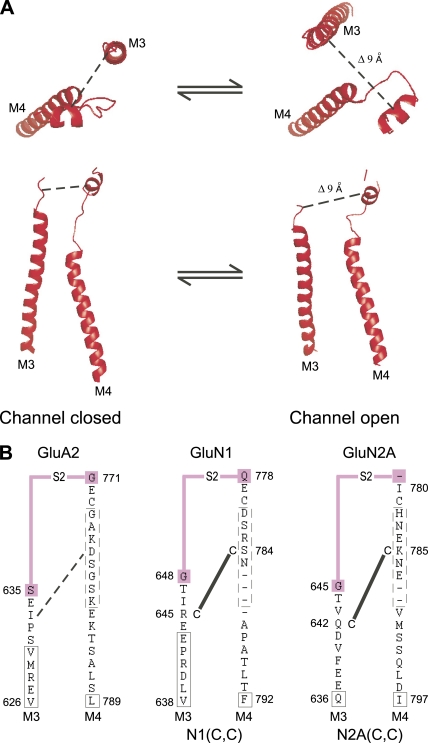

A single iGluR subunit contains four modular domains: the extracellular amino-terminal domain and ligand-binding domain (LBD), a transmembrane domain (TMD), and an intracellular C-terminal domain (Oswald et al., 2007; Traynelis et al., 2010; Mayer, 2011). The core domains necessary and sufficient for activation gating are the LBD (composed of S1 and S2) and TMD (composed of M1–M4) (Fig. 1 A). These core domains are coupled by three short polypeptide linkers (S1–M1, M3–S2, and S2–M4) that mediate ligand-induced conformational changes in the LBD to the opening of the channel pore. In the tetrameric assembly of an iGluR, the four M3 transmembrane segments form the pore and constitute the main channel-gating element (Kohda et al., 2000; Jones et al., 2002; Qian and Johnson, 2002; Sobolevsky et al., 2002; Yuan et al., 2005; Blanke and VanDongen, 2008; Chang and Kuo, 2008). Homologous to the evolutionarily linked K+ channel (Wo and Oswald, 1995; Wood et al., 1995; Chen et al., 1999; Panchenko et al., 2001; Kuner et al., 2003; Sobolevsky et al., 2009), the opening of the channel pore in iGluRs involves, in some form, movements of the M3 segments away from the central axis of the pore (Fig. 1 B). The M3–S2 linker that connects the LBD to the M3 segment must therefore be a central element of the gating machinery coupling conformational dynamics at the LBD to pore opening.

Figure 1.

The M3 transmembrane segment is the major channel-gating element in iGluRs. (A) Backbone structure of two glutamate receptor subunits (GluA2cryst; subunits B and C, Protein Data Bank accession no. 3KG2), each harboring an extracellular LBD (in gray) comprised of polypeptide segments S1 and S2, transmembrane segments M3 and M4, and their associated linkers M3–S2 and S2–M4. For clarity, the M1 transmembrane segment and the M2 pore loop are not shown. GluN1 is assumed to adopt the A/C conformation (red) and GluN2 the B/D conformation (blue) (Sobolevsky et al., 2009). The dashed line indicates point of view (looking down the ion channel) shown in B. Red and blue squares depict regions of intrasubunit cross-linking of the M3–S2 and S2–M4 linkers in GluN1 and GluN2A, respectively. Although there are limitations in comparing NMDA receptors to the AMPA receptor structure and the derived open-state structural model, for example, domain arrangements may be different (Stroebel et al., 2011), we use this information to illustrate general features of gating in iGluRs, specifically for the TMD. (B) Presumed gating movements of the M3 transmembrane segment leading to pore opening. (Left) Tetrameric arrangement of M3/M3–S2 and M4/S2–M4 adopting the A/C (~GluN1; red) and B/D (~GluN2A; blue) conformations in an antagonist-bound channel closed state (Sobolevsky et al., 2009). The M3 transmembrane helices line the channel pore (depicted with a dot), whereas the external helices surrounding this core are the M4 segments. (Right) Reorientation of the M3 segments in the channel open state as predicted from superposition of the GluA2cryst on the closed KcsA and the open Shaker K+ channels (Sobolevsky et al., 2009). In the present study, we restrict these gating rearrangements of M3 through intrasubunit cross-linking of the M3–S2 and S2–M4 linkers in GluN1 (A, red box) or GluN2A (A, blue box).

In the only intact iGluR structure of a homomeric AMPA receptor, the LBD–TMD linkers mediate an unprecedented symmetry mismatch between the LBD (twofold symmetry relative to central axis of receptor) and the ion channel (fourfold symmetry) by adopting different conformations in adjacent subunits (Sobolevsky et al., 2009). If this symmetry mismatch also exists in the NMDA receptor, it is likely to have important gating consequences because the functional unit within the receptor is thought to be a heterodimer containing a glycine-binding GluN1 and a glutamate-binding GluN2 subunit (Furukawa et al., 2005). Because of the different linker arrangements, the energetic mechanisms coupling ligand binding to pore opening may differ within an NMDA receptor heterodimer. Still, in an intact NMDA receptor, all four subunits must bind their respective ligands for subsequent pore opening to occur (Benveniste and Mayer, 1991a; Clements and Westbrook, 1991; Schorge et al., 2005), although the mechanism and structural basis for this concerted gating process are unknown.

To investigate subunit-dependent mechanisms driving pore opening in NMDA receptors, we identified means to physically constrain the M3–S2 linker by disulfide cross-linking it with the S2–M4 linker within specific NMDA receptor subunits, either GluN1 or GluN2A. Using single-channel recordings and kinetic analysis to define energetic effects on gating, we find that constraining M3–S2 in either GluN1 or GluN2A strongly reduced channel open probability. The most dramatic effect was on the late gating steps mediating pore opening where a long-lived, energetically stable open state was nearly abolished. In these late gating steps, we found a tight coupling across all NMDA receptor subunits; full pore opening would not occur unless all four subunits undertook their own intrasubunit gating actions. Thus, concerted gating in NMDA receptors requires equivalent intrasubunit movements of M3–S2 relative to S2–M4 occurring together across both GluN1 and GluN2 subunits.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mutagenesis and expression

Cysteine substitutions in the rat GluN1a (NCBI Protein database accession no. P35439) and GluN2A (accession no. Q00959) subunits were generated using PCR-based methods (Sobolevsky et al., 2007). As a reference and background for mutagenesis, we used a GluN2A construct in which a reactive cysteine near the N terminus of S1 was mutated to an alanine (C399A). Xenopus laevis oocytes were prepared, injected with cRNA, and maintained as described previously (Sobolevsky et al., 2007). Recordings were made 2–5 d after injection. For mammalian cell expression, human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were cotransfected with cDNA for GluN1 and GluN2A subunits, as well as a vector for enhanced green fluorescent protein (pEGFP-Cl; Takara Bio Inc.), at a ratio of (in µg) 1:1:1, using Fugene 6 (Roche). Recordings were made 24–72 h after transfection.

Macroscopic current recordings and analysis

Macroscopic currents of Xenopus oocytes were recorded at room temperature (20–23°C) using two-microelectrode voltage clamp (TEV-200A; Dagan Corporation) with Cell Works software (npi electronic GmbH). Microelectrodes were filled with 3 M KCl and had resistances of 1–4 MΩ. The external solution consisted of (in mM): 115 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 0.18 BaCl2, 5 HEPES, and 100 µM EDTA, pH 7.2 (NaOH), unless otherwise noted. All reagents including glycine (20 µM) and glutamate (200 µM), competitive antagonists for GluN1, 5,7-dichlorokynurenic acid (DCKA; 10 µM), and for GluN2, DL-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (APV; 100 µM), and the reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT; 4 mM) were applied with the bath solution. All reagents were obtained from Roche or Sigma-Aldrich.

Steady-state reactions.

Steady-state reactions were quantified at a holding potential of −60 mV. Baseline glutamate-activated current amplitudes (Ipre) were established by three to five 15-s applications of glutamate and glycine. All agonist or any other reagent applications were separated by 30–120-s washes in agonist-free solution. 4 mM DTT was applied for 2 min in the absence of agonist but in the presence of the competitive antagonists DCKA (for GluN1) and APV (for GluN2). We found that DTT more effectively potentiated current amplitudes under these conditions than when applied in the presence of agonists. After DTT exposure, current amplitudes (Ipost) were determined using three to five agonist applications. The change in glutamate-activated current amplitude, expressed as a percentage (percent change), was calculated as: = (Ipost − Ipre)/Ipre × 100. In certain instances, we corrected for observed current rundown by fitting a single-exponential function to a minimum of three pre-DTT glutamate-activated current amplitudes.

MK801 inhibition.

MK801 is an irreversible (on the timescale of tens of minutes) open-channel blocker at hyperpolarized potentials (Huettner and Bean, 1988). MK801 inhibition was assessed with either 1 µM (Fig. 3, A–C) or 25 nM (Fig. 3 D–H) MK801 after agonist-induced current amplitudes had reached steady state. The change in glutamate-activated current amplitude, expressed as a percentage (percent change), was calculated as: = (Ipost − Ipre)/Ipre × 100. For DTT and antagonist treatments, percent change was calculated relative to the current amplitudes preceding these treatments but after MK801 block. The kinetics of MK801 inhibition were fitted with either single- or biexponential functions. A higher-order exponential function was used only when it qualitatively minimized the residual currents (Ires) of these fits (see bottom graphs in Fig. 3, D and E).

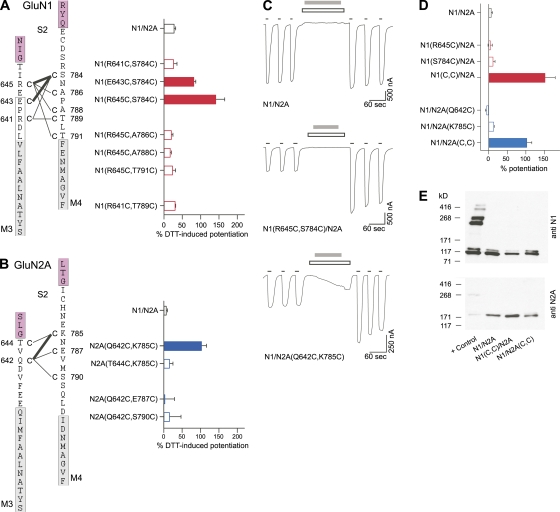

Figure 3.

A subset of cell surface NMDA receptors with double-cysteine–substituted GluN1 or GluN2A is resistant to pore block by MK801. To optimize current amplitudes in these experiments, we injected WT GluN1/GluN2A at 1 ng/µL and GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A and GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) at 10 ng/µL into Xenopus oocytes. (A and B) Example recordings depicting steady-state MK801 inhibition of NMDA receptor–mediated macroscopic currents. MK801 (open bar; 1–2 µM; 1 min), applied in the presence of agonists (thin lines), inhibited current amplitudes for GluN1/GluN2A (A), GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A (B), and GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) (not depicted) receptors. Subsequent application of DTT (filled bar) in the channel closed state (as in Fig. 2 C) significantly potentiated current amplitudes of the double-cysteine–substituted receptor (B) relative to WT GluN1/GluN2A (A). (C) Mean percent change (±SEM; n ≥ 4) in current amplitudes either immediately after MK801 (MK801) or after MK801, but with an intervening treatment by DTT in the presence of antagonists (DTT) or antagonists alone (antag.). For DTT and antagonist-alone treatments, percent change was calculated relative to the current amplitudes preceding these treatments but after MK801 block. Negative and positive values represent current inhibition and potentiation, respectively. Filled bars indicate values significantly different from those of WT GluN1/GluN2A receptors (P < 0.05). (D and E) 25 nM MK801 was applied in the presence of agonists until steady-state current inhibition was reached. (E, right) For GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A, MK801 was also applied to DTT-potentiated currents. Single- (gray dashed lines) and biexponential (green dashed lines) fits to MK801-mediated current inhibition are shown, as well as the residuals (Ires) to the two fits. For GluN1/GluN2A, single-exponential fits were sufficient to describe the time course of MK801-mediated current inhibition, whereas for GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A, biexponential fits were required, as determined by qualitative minimization of Ires. (F) Normalized MK801-mediated inhibition of currents with the overlayed best fits (dashed lines). (G) Averaged time constants of single-exponential fits (τ), as well as the fast (τf) and slow (τs) components of the biexponential fits (±SEM) to MK801-mediated current inhibition. (H) Averaged percentage of area (±SEM) occupied by each component of the exponential fits.

Single-channel recordings and analysis

Single-channel recordings were made at steady state using the cell-attached configuration on HEK 293 cells. Currents were acquired using an amplifier (Axopatch 200B; Molecular Devices), filtered at 10 kHz (four-pole Bessel filter), and digitized at 50 kHz (ITC-16 interfaced with Patchmaster; HEKA). The bath solution consisted of (in mM): 150 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, and10 HEPES, pH 7.2 (NaOH). Although gating in NMDA receptors can be modulated by external [H+] (Erreger et al., 2005a), we used pH 7.2 rather than a high pH to allow direct comparison between the HEK cell and oocyte recordings. Pipette electrodes were pulled from thick-walled borosilicate glass (Warner Instruments) and fire-polished immediately before use. The pipettes were filled with an external solution (pipette) consisting of the bath solution supplemented with 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM Gly, and 1 mM glutamate. Final resistances were 10–40 MΩ when filled with pipette solution and measured in the bath solution. A voltage of +100 mV was applied through the recording pipette to elicit inward sodium currents. In certain instances, patches were broken into the whole cell configuration to note the resting Vm, which was typically from −11 to −30 mV, after the recording period had ended.

For experiments assessing the effect of DTT on NMDA receptor single-channel activity, we paralleled the DTT application protocol used to efficiently reduce the disulfide bonds in our whole cell oocyte recordings (see Fig. 2 C). We pretreated the NMDA receptor–transfected HEK cells with 4 mM DTT, 10 µM DCKA, and 100 µM APV in our bath solution and then came in with the patch pipette (containing the agonists but no DTT) under positive pressure to form the cell-attached seal. For whole cell recordings in oocytes, current amplitudes of the double-cysteine–substituted receptors gradually decreased over time after washout of DTT, presumably because of disulfide bond reformation (not depicted). However, for the single-channel recordings, the DTT-induced high activity levels remained constant even in recordings lasting up to 50 min. We do not understand this apparent lack of disulfide bond reformation in the cell-attached mode, but it may indicate that the glass pipette does not provide an absolute oxidizing environment.

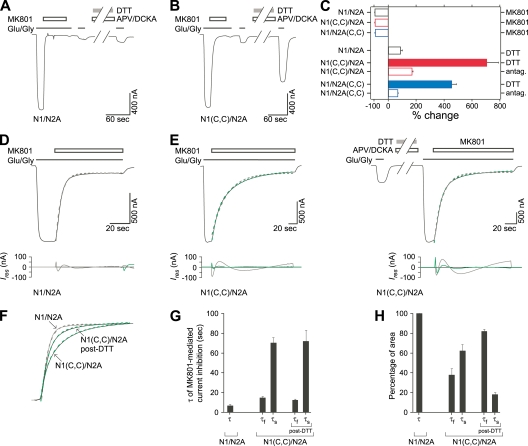

Figure 2.

DTT-induced potentiation of macroscopic currents in NMDA receptors containing intrasubunit double-cysteine substitutions in GluN1 or GluN2A. (A and B) NMDA receptors with intrasubunit GluN1- or GluN2A-specific double-cysteine substitutions were assayed for DTT-induced changes in macroscopic current amplitudes using two-microelectrode voltage clamp in Xenopus oocytes. Double-cysteine–substituted GluN1 (A) or GluN2A (B) subunits were coexpressed with WT GluN2A or GluN1 subunits, respectively. (Left) Schematic representation of regions around M3–S2 and S2–M4 linkers. Positions substituted with cysteine are indicated with a “C” and numbered next to the endogenous residue. Tested pairs of cysteines are shown with a connecting line. Darker lines indicate pairs that showed significant DTT-induced current potentiation relative to GluN1/GluN2A and hence can presumably spontaneously cross-link. Numbering is for the mature protein. Proximal parts of S2 and the hydrophobic segments M3 and M4 are colored as magenta and gray, respectively. Boxed regions around the hydrophobic segments represent the α-helical extent of the transmembrane segments in an AMPA receptor structure (Sobolevsky et al., 2009). (Right) Mean percent change (±SEM; n ≥ 4) of current amplitudes after DTT. In the recording protocol for the GluN1 double-cysteine substitutions, (A) DTT was applied continuously in the presence and absence of agonists for at least 2 min (raw recordings not depicted). The recording protocol for the GluN2A double-cysteine substitutions (B) was identical to those in C. Filled bars indicate values significantly different from those of WT receptors (P < 0.05). Our experiments focused on GluN1(R645C,S784C)/GluN2A and GluN1/GluN2A(Q642C,K785C) receptors. (C) Representative membrane currents (holding potential, −60 mV) in Xenopus oocytes injected with WT GluN1/GluN2A, GluN1(R645C,S784C)/GluN2A, or GluN1/GluN2A(Q642C,K785C) receptors. Hereafter, GluN1(R645C,S784C) and GluN2A(Q642C,K785C) are referred to as GluN1(C,C) and GluN2A(C,C), respectively. Currents were elicited by coapplication of 20 µM glycine and 200 µM glutamate (thin black lines). 4 mM DTT (2 min; gray bars), applied in the presence of competitive antagonists DCKA (10 µM) and APV (100 µM) (open boxes), strongly potentiated subsequent current amplitudes in the double-cysteine–substituted receptors. (D) Mean percent change (±SEM; n ≥ 4) of current amplitudes after DTT. Filled bars indicate values significantly different from those of WT receptors (P < 0.05). (E) Western blot analysis of membrane proteins purified from Xenopus oocytes under nonreducing conditions. Formation of intersubunit cross-linking, either homomeric or heteromeric, was assayed with anti-GluN1 (top) or anti-GluN2A (bottom) antibodies. The “+ Control” is GluN1(N521C,L777C)/GluN2A(E516C,L780C) receptors that form intersubunit dimers (Furukawa et al., 2005). Expected molecular weights are: monomeric GluN1 (114 kD) and GluN2A (173 kD), homodimeric GluN1 (228 kD) and GluN2A (346 kD), and heterodimeric GluN1/GluN2A (287 kD). Other than the monomeric bands, no apparent homomeric or heteromeric dimer bands were detected for GluN1/GluN2A or either of the double-cysteine–substituted receptors, although dimers were present for the “+ Control” (n = 4).

Data (in .dat format) were transferred to QuB (http://www.qub.buffalo.edu) for analysis. Each recording was visually inspected in its entirety for multiple simultaneous openings, signal-to-noise fluctuations, high frequency artifacts, and baseline drifts. For GluN1/GluN2A receptors without DTT and all receptors with DTT, the recordings consisted of long clusters of activity separated by seconds-long periods of zero activity, making it straightforward to detect more than one channel in the patch as simultaneous openings. In these cases, given the high Po (0.5–0.98) of GluN2A-containing receptors and the minutes-long duration (with 10,000–320,000 events) of recordings without any apparent multiple openings, these recordings certainly contained only a single channel in the patch. For recordings of GluN1(R645C,S784C)/GluN2A and GluN1/GluN2A(Q642C,K785C) without DTT (Po < 0.02), it was more challenging to detect single-channel patches. First, many patches were recorded but excluded from analysis because of obvious simultaneous openings of multiple channels. Of the remaining patches, only minutes-long recordings (with 2,500–52,000 events) without any apparent simultaneous openings were further analyzed. According to Colquhoun and Hawkes (1990), a two-channel patch containing channels with a Po of 0.01 is expected to undergo at least one double opening every 200 single-opening events. Among our analyzed GluN1(R645C,S784C)/GluN2A and GluN1/GluN2A(Q642C,K785C) recordings, the least number of events recorded in a patch without any apparent double opening was 2,675. Therefore, we are reasonably confident that we analyzed patches containing only a single channel.

Further processing was done to eliminate occasional obvious brief noise spikes (e.g., high amplitude, stereotypical exponential-like decay, etc.) by matching them to the level of adjacent events using the “erase” function in QuB. Long periods of high noise were deleted with the remaining flanking segments separated as discontinuous segments. Baseline drift was corrected by resetting baseline to zero current levels. Processed data were idealized using the SKM algorithm after filtering to 12 kHz with a Gaussian digital filter. A conservative dead time of 0.15 ms was imposed across all recording files. The idealization protocol may have missed very fast events, and we did not correct for such missed events. Still, our goal was not to define an absolute kinetic mechanism of NMDA receptor gating, but rather to compare kinetic mechanisms across conditions. For our analysis, we assume that missed events were largely equal across different experimental conditions.

Kinetic analysis was performed using the maximum interval likelihood (MIL) algorithm in QuB. State models with increasing open and closed states were constructed and fitted to the recordings until log-likelihood (LL) values improved by <10 LL units/added state. We used a linear fully liganded state model containing three closed states, two desensitized states, and two to four open states (see Figs. 7 A and 8 A) of NMDA receptor gating (Kussius and Popescu, 2009). All recordings of GluN1/GluN2A and double-cysteine–substituted receptors were best fit by five closed and two to four open states (all additional open states branched out of the first one). The open-time components, comprising one common short-duration (O1) and up to three long-duration (O2-4) intervals, arise from modal gating of NMDA receptors (Popescu and Auerbach, 2003). The long open events O3 and O4 did not occur in every patch, either of wild-type (WT) or double-cysteine–substituted receptors. In addition, for the double-cysteine–substituted receptors, the overall number of modal shifts to these long open states was low, simply because of their low Po of <0.03. Therefore, we could not perform any statistical analysis of shifts in modal gating. Rather, for ease of analysis and comparison, we aggregated the two to four open-time components into two: one short-duration (O1) and one long-duration (O2) component (Fig. 7 A). Time constants and the relative areas of each component, the transition rate constants, as well as mean closed time (MCT) and mean open time (MOT) were averaged for each receptor without and with DTT pretreatment and compared with each other.

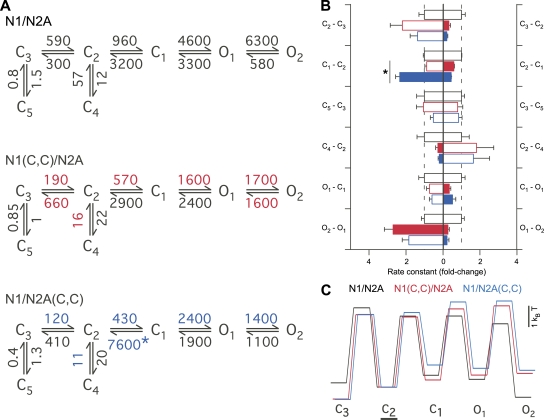

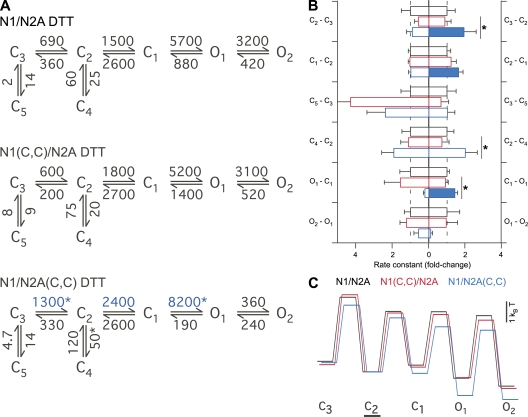

Figure 7.

Effects of the intrasubunit GluN1 or GluN2A cross-links on the kinetic mechanism of NMDA receptor activation. (A) Sequential-state model (Kussius and Popescu, 2009) of NMDA receptor activation with the rate constants (s−1) of transitions averaged from fits of individual single-channel recordings. Significant differences (P < 0.05) relative to WT are indicated with colored rate constants. Significant differences (P < 0.05) between GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A and GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) are indicated with asterisks. (B) Mean fold change (±SEM) in rate constants relative to GluN1/GluN2A. The left and right axes show the reverse and forward rate constants, respectively. Significant differences (P < 0.05) relative to WT and between GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A and GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) are indicated with filled bars and asterisks, respectively. (C) Free energy landscape plotted with respect to C2. The off-pathway steps to and from C4 and C5 are excluded. The three traces are horizontally offset for clarity.

Figure 8.

After exposure to DTT, NMDA receptors composed of WT or double-cysteine–substituted subunits displayed comparable kinetic behavior. Kinetic analysis, as in Fig. 7, for single-channel patches exposed to DTT. (A) Sequential-state model (Kussius and Popescu, 2009) of NMDA receptor activation with the rate constants (s−1) of transitions averaged from fits of individual single-channel recordings. Significant differences (P < 0.05) relative to WT are indicated with colored rate constants. Significant differences (P < 0.05) between GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A and GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) are indicated with asterisks. (B) Mean fold change (±SEM) in rate constants relative to GluN1/GluN2A. The left and right axes show the reverse and forward rate constants, respectively. Significant differences (P < 0.05) relative to WT and between GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A and GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) are indicated with filled bars and asterisks, respectively. (C) Free energy landscape plotted with respect to C2. The off-pathway desensitization-related steps to and from C4 and C5 are excluded. The three traces are horizontally offset for clarity.

Biochemistry

2–3 d after injection of ~10 ng cRNA per oocyte, 10 healthy oocytes expressing WT GluN1/GluN2A or cysteine substituted GluN1/GluN2A receptors were selected for membrane purification. For a positive control, we used GluN1(N521C,L777C)/GluN2A(E516C,L780C) receptors that form disulfide bond–stabilized intersubunit dimers (Furukawa et al., 2005). Oocytes were washed with 1× PBS, lysed in 1 ml of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris and 0.5 mM N-ethylmaleimide [NEM]), and centrifuged (3,000 rpm for 3 min at 4°C) to separate out the yolk. Recovered supernatant was centrifuged (40,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C). The pellet was washed with 1 ml PBS and recentrifuged (40,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C). The resulting pellet was resuspended in 87 µl of solubilization buffer (20 mM Tris, 0.5 mM NEM, 50 mM NaCl, and 1/1,000 protease inhibitor cocktail) without detergent and bath sonicated in ice water four times (15 s on/15 s off). Detergents (1% Triton X-100 and 0.3% sodium deoxycholate [monohydrate]) were added to the solubilization buffer to a final volume of 100 µl and incubated with gentle agitation at 4°C for 1 h. Solubilized proteins were centrifuged (40,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C), and the recovered supernatant contained the purified membrane fraction.

Membrane fractions were run on a 5% SDS-PAGE gel under nonreducing conditions. Proteins were transferred to 0.45-mm nitrocellulose membranes by semi-dry transfer (Bio-Rad Laboratories) using Bjerrum-Schafer-Nielsen buffer. Membranes were probed with either mouse anti-NMDAR1 (1:300; Millipore) or rabbit anti-NMDAR2A (1:300; Millipore). Blots were developed with Western Blotting Luminol Reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and exposed to chemiluminescence film (Biomax; Kodak).

Statistics

Data analysis was done using Igor Pro (WaveMetrics), QuB, and Excel (Microsoft). For analysis and illustration, leak currents were subtracted from total currents. Results are presented as mean ± SEM. An ANOVA was used to define statistical differences. The Tukey or Dunnett tests were used for multiple comparisons of means. Significance was defined at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Intrasubunit disulfide cross-linking of the M3–S2 and S2–M4 linkers in GluN1 and GluN2A NMDA receptor subunits

In an iGluR subunit, the M3–S2 linker connects the LBD to the M3 transmembrane segments, the main channel-gating element (Fig. 1). To dissect out subunit-dependent mechanisms of pore opening in NMDA receptors, we sought to constrain the gating movements of M3–S2. Therefore, we substituted cysteines in M3–S2 as well as S2–M4 (connecting the LBD to M4) to generate intrasubunit disulfide bonds (Fig. 2). Our experimental design used spontaneously formed disulfide bonds rather than oxidizing agent–induced formation of disulfide bonds because the latter can more readily trap receptors in rarely visited conformations. We tested multiple pairs of M3–S2 and S2–M4 cysteine-substituted positions in GluN1 (Fig. 2 A) and GluN2A (Fig. 2 B), anticipating that spontaneously formed disulfide bonds could be broken by the reducing agent DTT and that, if these constraints affected gating, treatment with DTT would yield significant changes in current amplitudes.

For each subunit, we identified a pair of positions displaying the anticipated phenotype: for GluN1 R645 in M3–S2 and S784 in S2–M4, and for GluN2A Q642 in M3–S2 and K785 in S2–M4. Exposure of the double-cysteine–substituted receptors GluN1(R645C,S784C)/GluN2A or GluN1/GluN2A(Q642C,K785C) (hereafter referred to as GluN1(C,C) and GluN2A(C,C), respectively) to extracellularly applied DTT significantly potentiated whole cell current amplitudes (percent potentiation; mean ± SEM; 151 ± 28%, n = 11, and 102 ± 14%, n = 8, respectively) compared with GluN1/GluN2A (5.6 ± 3.5%, n = 5) (Fig. 2, C and D). (Note that DTT most effectively potentiated current amplitudes of the double-cysteine–substituted receptors when it was applied in the presence of competitive antagonists; see Materials and methods.) In contrast, NMDA receptors containing a corresponding single-cysteine substitution showed no significant DTT-induced current potentiation (Fig. 2 D). Therefore, we conclude that DTT-induced current potentiation in the double-cysteine–substituted receptors results from reduction of spontaneously formed disulfide bonds between substituted cysteines. The observed disulfide cross-linking between M3–S2 and S2–M4 was within a single subunit (intrasubunit) rather than between like subunits (e.g., substituted cysteine in M3–S2 of one GluN1 cross-linking with substituted cysteine in S2–M4 of the other GluN1 subunit), because, in contrast to the positive control, no dimers were detected for either GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A or GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) (Fig. 2 E).

NMDA receptors with cross-linked GluN1 or GluN2A subunits are resistant to persistent pore block by MK801

As an initial assessment of whether constraining the M3–S2 linkers affects gating, we used MK801, an irreversible open-channel pore blocker (Huettner and Bean, 1988; Jahr, 1992). The treatment of GluN1/GluN2A, GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A, or GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) with a high concentration (1 µM) of MK801 strongly inhibited current amplitudes (percent inhibition: 95 ± 0.2%, n = 4; 94 ± 1.4%, n = 4; and 92 ± 0.9%, n = 9, respectively) (Fig. 3, A–C). Surprisingly, however, the remaining MK801-resistant current for GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A and GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) was significantly potentiated by DTT applied in the presence of competitive antagonists (percent potentiation: 704 ± 88%, n = 4, and 453 ± 35%, n = 8, respectively), compared with that in GluN1/GluN2A (86 ± 15%, n = 4) (Fig. 3, A–C). This observed effect was specific to DTT, as the application of antagonists alone on MK801-treated GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A or GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) receptors did not produce significant current potentiation (Fig. 3 C). Thus, a population of double-cysteine–substituted receptors is resistant to persistent pore block by MK801 but sensitive to DTT-induced current potentiation. In conjunction with the later single-channel results, we conclude that this MK801-resistant component of double-cysteine–substituted receptors is the portion of cell surface receptors containing intact DTT-sensitive cross-links. In contrast, the portion of cell surface receptors that undergo pore block by MK801 likely contains un–cross-linked disulfides. The application of the strong oxidizing reagent copper(II):phenanthroline did not affect the pre-DTT current amplitudes (not depicted), suggesting that the un–cross-linked disulfides exist as superoxide species, such as −SOH, −SO2H, or SO3H forms (Cline et al., 2004).

To investigate further these redox-heterogenous populations of cell surface receptors, we quantified the rate of MK801 block of WT and GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A receptors. A low concentration of MK801 (25 nM) inhibited whole cell current amplitudes of WT receptors, the rate of which was well described by a single-exponential function (time constant τ = 6.8 ± 0.6 s, n = 5) (Fig. 3, D and G). In contrast, MK801-mediated (25 nM) decay of whole cell current amplitudes of GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A was best fitted (see Materials and methods) with a biexponential function (τf = 14.8 ± 1.4 s and τs = 70.3 ± 5.2, n = 4) (Fig. 3, E and G). DTT treatment of GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A did not affect the kinetics of the biexponential components of MK801 inhibition (τf = 12.5 ± 0.9 s and τs = 71.9 ± 11, n = 5) (Fig. 3, F and G) but reversed their fractional contributions (post-DTT: τf = 37.7 ± 1.9% and τs = 62.3 ± 6.4% vs. pre-DTT: τf = 82.1 ± 1.9% and τs = 17.3 ± 1.9%) (Fig. 3 H), resulting in an increase in the overall rate of MK801 block (Fig. 3 F).

We interpret these data as follows. For GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A cell surface receptors, τf, which approaches the faster single-exponential function in WT receptors, underlies MK801 block of the un–cross-linked double-cysteine–substituted receptors. Conversely, τs represents MK801 block of the cross-linked receptors. Before DTT, the un–cross-linked and cross-linked receptors account for ~40 and ~60% of the macroscopic current amplitudes. DTT treatment breaks the disulfide bonds in the cross-linked receptors, resulting in ~80% of the macroscopic currents now being carried by un–cross-linked receptors. This biophysical assessment of the properties of MK801 block reveals that the heterogenous population of cell surface double-cysteine–substituted receptors significantly complicates the macroscopic current profile of these receptors. To more cleanly study the gating effects of the intrasubunit cross-links, we therefore used single-channel recordings

Constraining relative movements of M3–S2 and S2–M4 in either GluN1 or GluN2A with intrasubunit disulfide cross-links dramatically impairs NMDA receptor activation gating

Fig. 4 (left) shows representative steady-state single-channel recordings of GluN1/GluN2A (A), GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A (B), or GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) (C) receptors acquired in the cell-attached mode on transiently transfected HEK cells. For each receptor, a parallel set of recordings was made from separate HEK cells pretreated with DTT (Fig. 4, right; see Materials and methods). Currents were recorded in the cell-attached mode at a pipette potential of +100 mV with saturating concentrations of glycine (0.1 mM) and glutamate (1 mM) in the pipette. The recordings shown as well as all others used for subsequent analysis were performed on patches that contained a single channel (see Materials and methods).

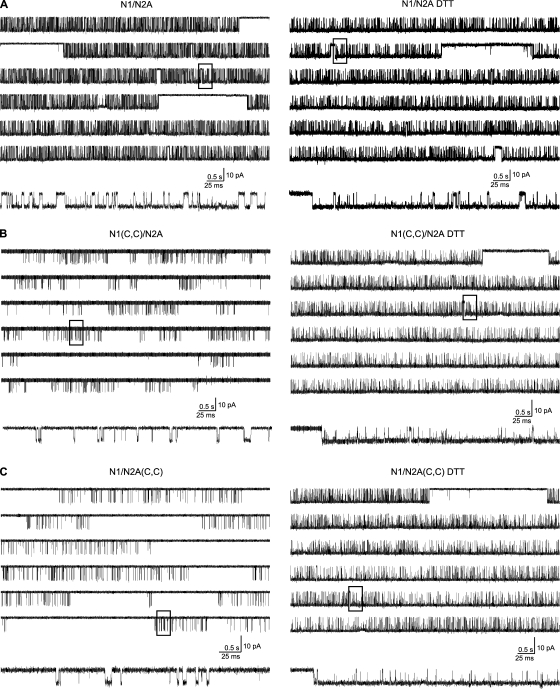

Figure 4.

NMDA receptors with intrasubunit GluN1 or GluN2A disulfide cross-links show dramatically reduced single-channel activity that can be reversed by DTT. (A–C) Recordings of on-cell patches containing single GluN1/GluN2A (A), GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A (B), or GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) (C) receptors under steady-state conditions (0.1 mM glycine and 1 mM glutamate; digitized at 50 kHz, filtered at 1 kHz) from transiently transfected HEK cells. For recordings shown on the right, cells were exposed to 4 mM DTT in the presence of antagonists DCKA (10 µM) and APV (100 µM) before forming the on-cell patches. For each, the bottom trace is an expanded view (filtered at 5 kHz) of the respective boxed regions. The left and right recordings are from different on-cell patches.

Qualitatively, the double-cysteine–substituted receptors, compared with WT GluN1/GluN2A, displayed considerably reduced single-channel activity, with only flickery short-duration openings apparent (Fig. 4, B and C, left). Strikingly, the predominant long-duration openings typical in WT receptors were essentially absent in double-cysteine–substituted receptors (Fig. 4, left, bottom traces). Nevertheless, there were similarities between the single-channel activity profiles; like GluN1/GluN2A, the double-cysteine–substituted receptors showed: (a) bursts of activity separated by long periods of no activity, (b) no obvious subconductance levels, and (c) comparable unitary current amplitudes. These similarities suggest that basic NMDA receptor gating behavior was intact in the double-cysteine–substituted receptors. Importantly, the observed gating differences in the double-cysteine–substituted NMDA receptors were mainly, if not exclusively, a result of the intrasubunit disulfide cross-links because with DTT treatment, the double-cysteine–substituted receptors, like WT, showed comparable high frequency and long-duration channel openings (Fig. 4, right).

Table I summarizes the quantified single-channel properties for WT and cross-linked NMDA receptors. Importantly, cross-linking M3–S2 and S2–M4 in either GluN1 or GluN2A did not affect unitary current amplitudes. Rather, the constraints drastically reduced equilibrium channel open probability (eq. Po; ~30- and 75-fold, respectively) compared with GluN1/GluN2A. This reduction in equilibrium channel open probability resulted mainly from a decrease in MOT with a corresponding increase in MCT. Interestingly, although MOT was similarly affected, MCT was differentially affected in GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A and GluN1/GluN2A(C,C), hinting at subunit-specific contributions to gating transitions restricted to channel closed periods.

Table I.

Constraining relative movements of M3–S2 and S2–M4 in GluN1 or GluN2A disrupts NMDA receptor gating

| Subunits | n | I | eq. Po | MCT | MOT |

| pA | ms | ms | |||

| N1/N2A | 7 | −9.4 ± 0.6 | 0.61 ± 0.05 | 5.1 ± 0.7 | 8.3 ± 0.8 |

| N1(C,C)/N2A | 8 | −9.0 ± 0.6 | 0.021 ± 0.005a | 94 ± 20a | 1.2 ± 0.1a |

| N1/N2A(C,C) | 9 | −8.1 ± 0.4 | 0.008 ± 0.001a | 230 ± 34ab | 1.4 ± 0.1a |

| N1/N2A DTT | 5 | −8.3 ± 0.2 | 0.74 ± 0.09 | 7.5 ± 3.7 | 23 ± 4.9c |

| N1(C,C)/N2A DTT | 5 | −7.7 ± 0.5 | 0.79 ± 0.08 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 16 ± 5.3 |

| N1(C,C)/N2A DTT | 4 | −9.2 ± 0.8 | 0.96 ± 0.01 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 30 ± 5.9 |

Mean values (±SEM) for single-channel current amplitudes (I), equilibrium open probability (eq. Po), MCT, and MOT. Idealization and MIL fitting with five closed and two to four open states was done in QuB. A sequential-state model for GluN1/GluN2A NMDA receptor gating (Kussius and Popescu, 2009) was used. eq. Po is defined as the fractional occupancy of the open states in the MIL-fitted single-channel recordings. For statistical analysis, the non-DTT and DTT-exposed receptors were considered separately, with the control being the respective values in GluN1/GluN2A.

P < 0.05, relative to GluN1/GluN2A.

P < 0.05, GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A relative to GluN1/GluN2A(C,C).

P < 0.05, GluN1/GluN2A relative to GluN1/GluN2A DTT.

After exposure to DTT, GluN1/GluN2A, GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A, and GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) showed similar equilibrium channel open probability, MCT, and MOT (Table I). This result indicates that the low levels of gating activity in untreated double-cysteine–substituted receptors was because of the physical constraint of the disulfide cross-links between M3–S2 and S2–M4, an effect that can be fully reversed by breaking the disulfide bonds with DTT. Thus, constraining relative movements of M3–S2 and S2–M4 in either GluN1 or GluN2A deters NMDA receptor activation gating. DTT treatment increased single-channel activity, specifically MOT, in WT receptors (Table I). Because activity in GluN1/GluN2A, GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A, and GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) was comparable after DTT treatment, DTT must be having this same effect on the double-cysteine–substituted receptors. Nevertheless, the focus of the present study is on the gating effects of intrasubunit cross-link rather than any additional effects of DTT on WT or double-cysteine–substituted receptors. Hence, we restricted our analysis of the single-channel results to within the DTT-untreated and separately within the DTT-treated sets of recordings, not between them.

In summary, the physical constraint produced by the intrasubunit disulfide cross-links in either GluN1 or GluN2A dramatically impaired pore opening. Thus, the conformational freedom of the M3–S2 and S2–M4 linkers is critical to the energetics of the gating process, coupling ligand binding to ion channel pore opening. Further, when pore opening does occur in receptors with gating constraints in either subunit, they are of a single conductance level indistinguishable from WT receptors, suggesting that even though gating is constrained in only two of the four subunits, the two unconstrained subunits cannot gate independently.

Gating impairments in either GluN1 or GluN2A similarly impact multiple channel open and closed dwell-time components

To examine in more detail the effects of the subunit-specific gating constraints, we characterized the durations and relative areas of the individual components within the channel closed and open dwell-time histograms (Fig. 5). The kinetics of NMDA receptor activation contain at least four closed- and two open-time components (Gibb and Colquhoun, 1992; Banke and Traynelis, 2003; Popescu and Auerbach, 2003; Auerbach and Zhou, 2005). The analyzed single-channel records of GluN1/GluN2A (Fig. 5 A), GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A (Fig. 5 B), or GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) (Fig. 5 C) were best fit with five closed- and two to four open-time components (see Materials and methods), suggesting that the basic kinetic mechanism of activation gating is unaffected by the intrasubunit disulfide cross-links. Although two to four open-time components, comprising one common short-duration and up to three long-duration intervals arising from modal gating of NMDA receptors (Popescu and Auerbach, 2003), could be fitted to our single-channel dataset for each receptor, we collapsed them into two components, one short and one long duration, for ease of analysis and comparison.

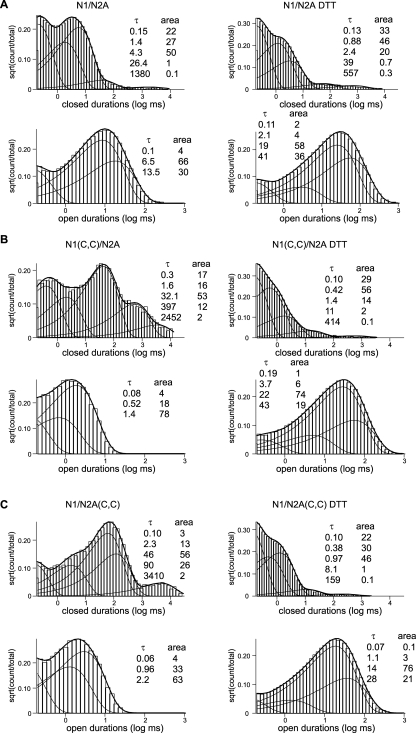

Figure 5.

Exponential fitting of composite histograms identify five closed and two to four open-time components. (A–C) Shut- (top) and open- (bottom) time–duration histograms of the same single-channel patches shown in Fig. 4. The shut-time–duration histograms were well fitted with five exponential components, whereas the open-time–duration histograms were well fitted with two to four exponential components. The time constants and relative areas of the exponential components are given in the insets.

For WT, the short-duration openings (τO1: 0.12 ± 0.01 ms) covered only a small fraction of the channel open time (aO1: 6 ± 1.1%), whereas the long-duration openings represented the predominant open-time component (τO2 and aO2: 8.7 ± 0.9 ms and 94 ± 1.1%) (Table II). Either GluN1 or GluN2A intrasubunit cross-links most profoundly affected gating by severely shortening the duration of the longer open-time component (τO2) (N1(C,C)/N2A, 1.6 ± 0.2 ms; and N1/N2C(C,C), 1.9 ± 0.9 ms) (Fig. 6 A, left). Although the shorter open-time component (τO1) was intact, its mean duration (0.25 ± 0.05 ms and 0.45 ± 0.09 ms, respectively) was increased by the intrasubunit cross-links (Fig. 6 A, left).

Table II.

Open- and closed-time components for NMDA receptors comprised of WT or double-cysteine–substituted subunits

| N1/N2A | N1(C,C)/N2A | N1/N2A(C,C) | DTT | |||

| N1/N2A | N1(C,C)/N2A | N1/N2A(C,C) | ||||

| n | 7 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| τO1 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.05 | 0.45 ± 0.09 | 3.0 ± 2.7 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 4.7 ± 2.2 |

| aO1 | 6 ± 1.1 | 25 ± 4.7 | 42 ± 9.6 | 10 ± 5.7 | 7.2 ± 1.2 | 17 ± 8.2 |

| τO2 | 8.7 ± 0.9 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.13 | 26 ± 7 | 17 ± 5.6 | 34 ± 6.9 |

| aO2 | 94 ± 1.1 | 75 ± 4.7 | 59 ± 9.6 | 90 ± 5.7 | 93 ± 1.2 | 83 ± 8.2 |

| τ1 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.004 |

| a1 | 20 ± 1.5 | 13 ± 1.3 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 31 ± 2.8 | 26 ± 3.5 | 31 ± 3.1 |

| τ2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 0.77 ± 0.16 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.42 ± 0.02 |

| a2 | 24 ± 3.4 | 14 ± 1.6 | 8.7 ± 1.4 | 38 ± 6.9 | 44 ± 5.6 | 37 ± 3.3 |

| τ3 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 38 ± 8.6 | 56 ± 9.0 | 3.8 ± 1.5 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| a3 | 52 ± 3.4 | 53 ± 3.6 | 48 ± 4.4 | 29 ± 8.6 | 29 ± 8.5 | 30 ± 6.6 |

| τ4 | 27 ± 5.6 | 210 ± 45 | 150 ± 27 | 35 ± 15 | 20 ± 4.9 | 9.1 ± 0.7 |

| a4 | 3.6 ± 1.3 | 17 ± 3 | 33 ± 4.9 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 7.0 ± 5.1 |

| τ5 | 1,800 ± 370 | 1,800 ± 310 | 2,900 ± 360 | 1,100 ± 450 | 1,200 ± 680 | 250 ± 52 |

| a5 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 3 ± 0.9 | 5.7 ± 0.9 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.02 |

Mean values (±SEM) for the exponential time constants (τ) and their relative areas (a) of the open- and closed-interval distributions. Idealization and MIL fitting with the sequential NMDA receptor gating model comprising five closed- and two open-channel states was done in QuB (see Materials and methods). These data are shown as ratios relative to WT receptors in Fig. 6.

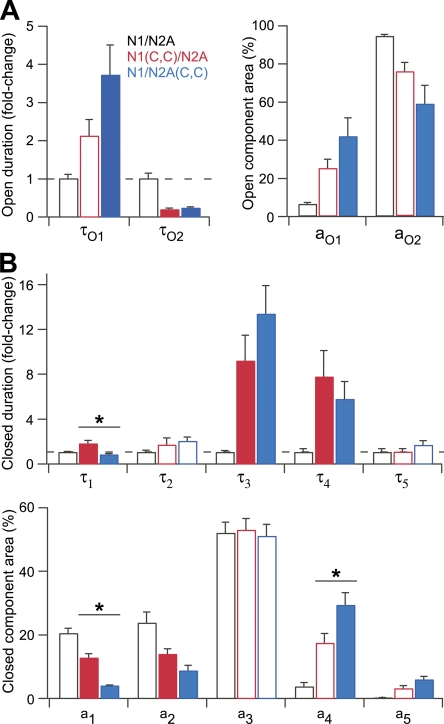

Figure 6.

NMDA receptors with intrasubunit GluN1 or GluN2A cross-links display largely symmetrical changes in multiple open- and closed-time components. (A, left) Mean fold change (±SEM) in duration of open-time components as determined by MIL fitting of single-channel recordings (see Materials and methods). Although single-channel records (in the cell-attached configuration) comprised two to four open-time components arising from modal gating behavior of NMDA receptors (Popescu and Auerbach, 2003), they were combined for simplicity into aggregates of two states, one short duration (for N1/N2A, 0.12 ± 0.01 ms) and one long duration (for N1/N2A, 8.71 ± 0.9 ms) (see Table II). (Right) Mean relative areas (±SEM) of the open-time components. (B, top) Mean fold change in duration (±SEM) of closed-time components as determined by MIL fitting of single-channel recordings. For WT GluN1/GluN2A, the time constants were (ms): τ1 0.14 ± 0.01, τ2 1.03 ± 0.13, τ3 4.16 ± 0.4, τ4 26.9 ± 5.6, and τ5 1,789 ± 366 (see Table II). (Bottom) Mean relative areas (±SEM) of the closed-time components. Significant differences (P < 0.05) relative to WT and between GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A and GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) are indicated with filled bars and asterisks, respectively.

Of the five closed-time components, the GluN1 and GluN2A intrasubunit cross-links increased the same two long-duration components (τ3 and τ4; τ3: N1/N2A, 4.2 ± 0.4 ms; N1(C,C)/N2A, 38.1 ± 8.6 ms; and N1/N2A(C,C), 55.5 ± 9 ms; and τ4: 26.9 ± 5.6 ms; 208 ± 45 ms; and 154 ± 27 ms, respectively) (Figs. 6 B, top). The relative area shifted away from the shorter duration (a1 and a2) and toward the longer duration (a4 and a5) closed-time components (Fig. 6 B, bottom). Intriguingly, the shortest duration closed-time component (τ1) was prolonged, albeit modestly, exclusively by the GluN1 intrasubunit cross-links (0.14 ± 0.005 ms, 0.25 ± 0.04 ms, and 0.11 ± 0.01 ms, respectively), with its relative area (a1) reduced to significantly different degrees by the cross-links in the different subunits (20.4 ± 1.5%, 12.6 ± 1.4%, and 3.7 ± 0.3%, respectively) (Fig. 6 B). In summary, constraining relative movements of M3–S2 and S2–M4 in either GluN1 or GluN2A decreases long channel openings and consequently increases receptor dwell times in long-duration channel closed states.

The GluN1 and GluN2A subunits contribute equally to pore-opening steps

To define subunit-specific contributions to pore-opening steps, we fitted a previously described linear model of NMDA receptor activation (Fig. 7 A) (Popescu and Auerbach, 2003; Auerbach and Zhou, 2005; Kussius and Popescu, 2009) to the idealized sequence of single-channel closed and open times using the MIL method (see Materials and methods). Because all single-channel recordings were done under saturating agonist concentrations, full occupancy of the agonist-binding sites was assumed, and thus explicit agonist-binding steps were excluded from the model. The linear scheme C3–C2–C1–O1–O2, comprising the three shortest duration closed-time components (τ3, τ2, and τ1) and the two aggregate open-time components (τO1 and τO2), represents the central activation pathway. C5, comprising the longest duration closed-time component (τ5), represents the main microscopic desensitized state (Dravid et al., 2008). C4, the other long-duration closed-time component (τ4), is perhaps also a desensitization-related state (Dravid et al., 2008). This sequential activation gating scheme, with the indicated connectivity of the off-pathway desensitization-related states (Fig. 7 A), fitted best the idealized data from each single-channel record as determined by the highest log (likelihood) value, with rate constants for GluN1/GluN2A receptors within the range of previously published values using comparable recording conditions and configurations (Kussius and Popescu, 2009).

In comparing the rate constants, the GluN1 and GluN2A intrasubunit cross-links had widespread and largely overlapping effects on the NMDA receptor activation mechanism (Fig. 7). All the central activation transitions, C3→C2→C1→O1→O2, as well as C4→C2, were similarly slowed in either GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A or GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) from those in GluN1/GluN2A (Fig. 6, A and B). The deactivation transitions O2→O1 and C2→C3 were similarly accelerated in GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A and GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) as compared with those in GluN1/GluN2A (Fig. 7, A and B). Interestingly, the reverse transition, C1→C2, was affected in a subunit-specific manner, with only GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) accelerating it (Fig. 7, A and B). Transitions to and from the main desensitization state C5 were unaffected by the intrasubunit cross-links (Fig. 7, A and B).

Free energy plots of the central activation pathway (excluding the desensitization-related states) showed that the GluN1- or GluN2-specific intrasubunit cross-links generally raised the energy barriers governing the kinetic steps of activation, shifting occupancy away from the open states and toward the longer duration closed states (Fig. 7 C). Notably though, C2–C1 exclusively underwent GluN2A-specific alteration, wherein restricting M3–S2 and S2–M4 separation in GluN2A resulted in decreased occupancy and therefore energetic destabilization of C1 (Fig. 7). In contrast, equivalent gating constraints in GluN1 did not affect C1 in such a manner.

DTT treatment of GluN1/GluN2A, GluN1(C,C)/GluN2A, and GluN1/GluN2A(C,C) restores similar kinetic parameters of activation gating (Fig. 8). Now the energetics of gating was overwhelmingly shifted toward channel opening (Fig. 8 C), especially for the double-cysteine–substituted ones as compared with their untreated counterparts (Fig. 7 C). Although there appears to be some effects of DTT beyond the reduction of disulfide cross-links, for example, faster rate of C2→C1 transition for all three receptor types after DTT treatment (compare Figs. 7 A and 8 A), presently we do not analyze them further. Nevertheless, these results further emphasize the impairment of pore opening generated by the intrasubunit disulfide cross-links and its reversibility through DTT-mediated breakage of such cross-links.

In summary, constraining separation of M3–S2 and S2–M4 in either GluN1 or GluN2A symmetrically slowed the late gating steps (C1–O1–O2), with entry rates into the long-lived open state being most dramatically reduced. Thus, GluN1 and GluN2 undergo tightly coupled conformational changes leading to pore opening. A single pre-open gating step (C2–C1), however, appears to be associated exclusively with the GluN2A subunit, suggesting some degree of subunit-independent early gating transitions before converging on concerted pore-opening movements across all subunits.

DISCUSSION

For NMDA receptors, defining kinetic mechanisms of activation gating has identified key energetic steps, including intermediate states between ligand binding and full channel opening (e.g., Banke and Traynelis, 2003; Auerbach and Zhou, 2005; Schorge et al., 2005; Kussius and Popescu, 2009). These states probably do not represent a single-protein conformation but rather a continuum of transiently stable conformations with similar energy profiles. To characterize the dynamics of activation gating in NMDA receptors, we took the novel approach of constraining the M3–S2 linker through intrasubunit cross-linking with S2–M4. The advantage of this approach is that it places a physical constraint at a specific location in the receptor, in these instances at a presumed pivotal juncture between the LBD and the ion channel. Restricting the relative intrasubunit movements of M3–S2 and S2–M4 greatly affected the energetics of gating, reducing channel open probability by 30–75-fold (Table I), while leaving intact the basic kinetic mechanism (e.g., a similar number of closed-/open-time components) (Figs. 4 and 5, and Table II). Through kinetic analysis, we addressed the contributions of this localized constraint in either the GluN1 or GluN2A subunit to the energetics of the gating process in NMDA receptors.

Intrasubunit separation of M3–S2 and S2–M4 during pore opening

An open-state iGluR structure does not exist. However, based on the closed-state AMPA receptor structure and ligand-bound LBDs and an open K+ channel, a general model of conformational changes occurring during gating has been proposed (Sobolevsky et al., 2009). One feature of this model is that during pore opening, the M3–S2 and S2–M4 linkers within a subunit undergo a rotational and/or linear separation of ~9 Å (Fig. 9 A). Although there are limitations in comparing the state-dependent positioning of these linkers in AMPA and NMDA receptor subunits because of significant differences in their sequences and sizes (e.g., Fig. 9 B), we assume a similar general conformational rearrangements in the NMDA receptor linkers. Hence, by disulfide cross-linking M3–S2 to S2–M4 in an individual NMDA receptor subunit, we covalently constrain their relative separation required for movement of M3 away from the central axis of the pore. Consequently, the most robust effects of the intrasubunit gating constraints was impairment of pore opening by greatly shortening the lifetime of the main long-lived channel open state, leading chiefly to brief or “flickery” openings (Figs. 4–6 and Table II).

Figure 9.

A model of the intrasubunit gating dynamics of M3–S2 and S2–M4 in the NMDA receptor. (A) Potential intrasubunit movements of the M3–S2 and S2–M4 linkers during pore opening. The channel closed conformations are from the antagonist-bound GluA2 (subunit C) crystal structure (Sobolevsky et al., 2009). The channel open conformations are based on homology modeling of the channel closed GluA2 structure with an open Shaker K+ ion channel and ligand-bound AMPA receptor LBD structure (Sobolevsky et al., 2009). Views from the top-down (top) and side (bottom) are shown. In this model, the centers of the M3–S2 linker (in the A/C subunit) and pre-M4 helix (dashed line) separate by ~9 Å in the transition from the closed- to the open-channel states. (B) Sequences of the M3–S2 and S2–M4 linkers in the GluA2, GluN1, and GluN2A subunits. Proximal parts of S2 are colored as magenta. In GluA2, the boxed region represents the transmembrane α-helical segments (in the A/C subunit), and the dashed boxed region depicts the pre-M4 helix. GluN1 is presumed to adopt the A/C and GluN2A the B/D conformations. Based on sequence alignment (Sobolevsky et al., 2009), the S2–M4 linkers in the GluN1 and GluN2A subunits have notable gaps, particularly in the presumed pre-M4 helix, complicating a direct comparison of NMDA receptor subunits to the GluA2 structure.

Intrasubunit gating actions of M3–S2 and S2–M4 are tightly coupled across all four subunits in an NMDA receptor

Activation gating in fully liganded NMDA receptors can generally be divided into early channel closed/pre-open gating steps (C3→C2→C1) and late gating steps mediating pore opening to its most stable state (C1→O1→O2) (Banke and Traynelis, 2003; Auerbach and Zhou, 2005; Kussius and Popescu, 2009). Gating constraints in either the glycine-binding GluN1 or glutamate-binding GluN2A subunits symmetrically affected the late gating steps mediating full pore opening (C1–O1 and O1–O2) to largely the same extent (Fig. 7). In addition, although open durations were greatly reduced in NMDA receptors with constrained subunits, these openings had the same conductance level as those found in WT receptors (Table I), rather than displaying prominent subconductance levels. Thus, if pore-opening movements of the M3–S2/M3 linker/transmembrane segment are restricted in one subunit (either GluN1 or GluN2A), pore-opening movements in the other nonconstrained subunits are also blocked. These results demonstrate that the intrasubunit pore-opening movements at the level of the linkers are tightly coupled across all four NMDA receptor subunits.

This tight coupling at the level of the linkers must be a manifestation of concerted gating in NMDA receptors wherein all four ligands—two glycine and two glutamate molecules—have to bind for subsequent channel pore opening to occur (Benveniste and Mayer, 1991a; Clements and Westbrook, 1991; Schorge et al., 2005). Here, we demonstrate that the conformational dynamics of specific structural elements, the M3–S2 and S2–M4 linkers and presumably their associated transmembrane segments M3 and M4, act in concert across all four subunits to open the pore in NMDA receptors. The gating transduction mechanism in NMDA receptors is an integrated process stretching from the LBD to the ion channel, with the linkers’ gating dynamics firmly incorporated across all kinetically detectable states, C3→C2→C1→O1→O2. Ligand interactions with and initial lobe closure of the LBD occurs before the receptor reaches the C3 conformational state (Kussius and Popescu, 2010).

In contrast to concerted pore opening in NMDA receptors, gating in the related AMPA receptor apparently occurs in a subunit-independent manner manifested as openings to multiple conductance levels (Rosenmund et al., 1998; Smith and Howe, 2000; Poon et al., 2010; Prieto and Wollmuth, 2010). Mechanisms underlying pore opening in AMPA receptors are unknown but may include subunit-independent movements of the M3 segments, the reentrant M2 pore loop, and/or other gating elements more proximal to the LBD such as the pre-M1 helix. Using homologous positions at the linkers of the AMPA receptor, for which a structure already exists (Sobolevsky et al., 2009), the cross-linking approach we used here could be a means to test for the mechanisms of subunit-independent gating in AMPA receptors.

Subunit-independent gating preceding ion channel pore opening

Immediately after ligand binding, the NMDA receptor undergoes at least two kinetically distinct channel closed/pre-open gating steps. In the sequential model of NMDA receptor activation, the slower pre-open gating step (C3→C2) must occur before the faster one (C2→C1) (Fig. 7) (Kussius and Popescu, 2009). Although the gating constraints in either the GluN1 or GluN2A subunit commonly affect overlapping rate constants in these two early gating steps, we do detect significant subunit-specific components. The reverse rate C1→C2 was exclusively affected by the GluN2A-gating constraints, being approximately twofold accelerated and resulting in C1 attaining a more unstable energetic state (Fig. 7). Although we do not presently explore this further, these results suggest some degree of subunit-independent isomerization events in pre-open gating steps of the NMDA receptor.

Such subunit-independent gating steps in the NMDA receptor have been suggested previously using GluN1- and GluN2-specific partial agonists (Banke and Traynelis, 2003; Erreger et al., 2005b), as well as noting GluN2A- versus GluN2B-specific differences in gating kinetics (Erreger et al., 2005a). Furthermore, a crystal structure of an iGluR has revealed key structural asymmetry between subunits in the extracellular domains, especially at the LBD–TMD linkers, transitioning to fourfold symmetry at the TMD (Sobolevsky et al., 2009). The subunit-independent pre-open gating steps, initiated in the LBD subsequent to clam-shell closure, may reflect structural differences in the LBDs where the functional pair is the GluN1/GluN2 heterodimer or the asymmetry between M3–S2s within a dimer pair (Sobolevsky et al., 2009). Hence, the asymmetry between subunits in the pre-open steps may reflect subunit-independent differences between the S2–M4s or relative movements of M3–S2 to S2–M4 in the different subunits. Future kinetic studies of NMDA receptors with constrained gating elements encompassing other LBD–TMD linkers will be needed to fully resolve the structural mechanisms coupling the energetics of ligand binding to channel pore opening.

Conclusion

Our results with the NMDA receptor are consistent both with previous functional experiments and structural features of iGluRs. In NMDA receptors, allosteric interactions occur between the two subunits in the LBDs (Benveniste and Mayer, 1991a,b; Lester et al., 1993; Regalado et al., 2001), presumably initiating concerted gating. However, from the LBD to the TMD, there appears to be some degree of subunit independence ultimately (re)converging on concerted pore-opening actions undertaken by all four subunits. This concerted pore opening in NMDA receptors may have functional significance in Ca2+ permeation, pore block, and receptor kinetics. Nevertheless, its biological significance as well as its structural basis remain unclear.

Acknowledgments

We thank Catherine Salussolia, George Zanazzi, William Borschel, and Drs. Gabriela Popescu and Stephen F. Traynelis for helpful discussions and/or comments on the manuscript. We also thank Janet Allopena for technical assistance with molecular biology.

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health RO1 grant from National Institute of Mental Health (MH066892 to L.P. Wollmuth), travel support from SUNY REACH (to L.P. Wollmuth and I. Talukder), and an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship (to I. Talukder).

Kenton J. Swartz served as editor.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- APV

- DL-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid

- DCKA

- 5,7-dichlorokynurenic acid

- DTT

- dithiothreitol

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney

- iGluR

- ionotropic glutamate receptor

- LBD

- ligand-binding domain

- MCT

- mean closed time

- MIL

- maximum interval likelihood

- MOT

- mean open time

- NMDA

- N-methyl-d-aspartate

- TMD

- transmembrane domain

- WT

- wild type

References

- Auerbach A., Zhou Y.. 2005. Gating reaction mechanisms for NMDA receptor channels. J. Neurosci. 25:7914–7923. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1471-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banke T.G., Traynelis S.F.. 2003. Activation of NR1/NR2B NMDA receptors. Nat. Neurosci. 6:144–152. 10.1038/nn1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste M., Mayer M.L.. 1991a. Kinetic analysis of antagonist action at N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptors. Two binding sites each for glutamate and glycine. Biophys. J. 59:560–573. 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82272-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste M., Mayer M.L.. 1991b. Structure-activity analysis of binding kinetics for NMDA receptor competitive antagonists: the influence of conformational restriction. Br. J. Pharmacol. 104:207–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanke M.L., VanDongen A.M.. 2008. The NR1 M3 domain mediates allosteric coupling in the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 74:454–465. 10.1124/mol.107.044115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H.R., Kuo C.C.. 2008. The activation gate and gating mechanism of the NMDA receptor. J. Neurosci. 28:1546–1556. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3485-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G.Q., Cui C., Mayer M.L., Gouaux E.. 1999. Functional characterization of a potassium-selective prokaryotic glutamate receptor. Nature. 402:817–821. 10.1038/990080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements J.D., Westbrook G.L.. 1991. Activation kinetics reveal the number of glutamate and glycine binding sites on the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. Neuron. 7:605–613. 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90373-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline D.J., Redding S.E., Brohawn S.G., Psathas J.N., Schneider J.P., Thorpe C.. 2004. New water-soluble phosphines as reductants of peptide and protein disulfide bonds: reactivity and membrane permeability. Biochemistry. 43:15195–15203. 10.1021/bi048329a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D., Hawkes A.G.. 1990. Stochastic properties of ion channel openings and bursts in a membrane patch that contains two channels: evidence concerning the number of channels present when a record containing only single openings is observed. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 240:453–477. 10.1098/rspb.1990.0048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dravid S.M., Prakash A., Traynelis S.F.. 2008. Activation of recombinant NR1/NR2C NMDA receptors. J. Physiol. 586:4425–4439. 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.158634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erreger K., Dravid S.M., Banke T.G., Wyllie D.J., Traynelis S.F.. 2005a. Subunit-specific gating controls rat NR1/NR2A and NR1/NR2B NMDA channel kinetics and synaptic signalling profiles. J. Physiol. 563:345–358. 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.080028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erreger K., Geballe M.T., Dravid S.M., Snyder J.P., Wyllie D.J., Traynelis S.F.. 2005b. Mechanism of partial agonism at NMDA receptors for a conformationally restricted glutamate analog. J. Neurosci. 25:7858–7866. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1613-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa H., Singh S.K., Mancusso R., Gouaux E.. 2005. Subunit arrangement and function in NMDA receptors. Nature. 438:185–192. 10.1038/nature04089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb A.J., Colquhoun D.. 1992. Activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors by L-glutamate in cells dissociated from adult rat hippocampus. J. Physiol. 456:143–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilf R.J., Dutzler R.. 2008. X-ray structure of a prokaryotic pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature. 452:375–379. 10.1038/nature06717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huettner J.E., Bean B.P.. 1988. Block of N-methyl-D-aspartate-activated current by the anticonvulsant MK-801: selective binding to open channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 85:1307–1311. 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahr C.E. 1992. High probability opening of NMDA receptor channels by L-glutamate. Science. 255:470–472. 10.1126/science.1346477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Lee A., Chen J., Cadene M., Chait B.T., MacKinnon R.. 2002. Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Nature. 417:515–522. 10.1038/417515a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K.S., VanDongen H.M., VanDongen A.M.. 2002. The NMDA receptor M3 segment is a conserved transduction element coupling ligand binding to channel opening. J. Neurosci. 22:2044–2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawate T., Michel J.C., Birdsong W.T., Gouaux E.. 2009. Crystal structure of the ATP-gated P2X(4) ion channel in the closed state. Nature. 460:592–598. 10.1038/nature08198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohda K., Wang Y., Yuzaki M.. 2000. Mutation of a glutamate receptor motif reveals its role in gating and delta2 receptor channel properties. Nat. Neurosci. 3:315–322. 10.1038/73877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuner T., Seeburg P.H., Guy H.R.. 2003. A common architecture for K+ channels and ionotropic glutamate receptors? Trends Neurosci. 26:27–32. 10.1016/S0166-2236(02)00010-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kussius C.L., Popescu G.K.. 2009. Kinetic basis of partial agonism at NMDA receptors. Nat. Neurosci. 12:1114–1120. 10.1038/nn.2361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kussius C.L., Popescu G.K.. 2010. NMDA receptors with locked glutamate-binding clefts open with high efficacy. J. Neurosci. 30:12474–12479. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3337-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester R.A., Tong G., Jahr C.E.. 1993. Interactions between the glycine and glutamate binding sites of the NMDA receptor. J. Neurosci. 13:1088–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M.L. 2011. Structure and mechanism of glutamate receptor ion channel assembly, activation and modulation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 21:283–290. 10.1016/j.conb.2011.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald R.E., Ahmed A., Fenwick M.K., Loh A.P.. 2007. Structure of glutamate receptors. Curr. Drug Targets. 8:573–582. 10.2174/138945007780618526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchenko V.A., Glasser C.R., Mayer M.L.. 2001. Structural similarities between glutamate receptor channels and K+ channels examined by scanning mutagenesis. J. Gen. Physiol. 117:345–360. 10.1085/jgp.117.4.345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon K., Nowak L.M., Oswald R.E.. 2010. Characterizing single-channel behavior of GluA3 receptors. Biophys. J. 99:1437–1446. 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popescu G., Auerbach A.. 2003. Modal gating of NMDA receptors and the shape of their synaptic response. Nat. Neurosci. 6:476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto M.L., Wollmuth L.P.. 2010. Gating modes in AMPA receptors. J. Neurosci. 30:4449–4459. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5613-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian A., Johnson J.W.. 2002. Channel gating of NMDA receptors. Physiol. Behav. 77:577–582. 10.1016/S0031-9384(02)00906-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regalado M.P., Villarroel A., Lerma J.. 2001. Intersubunit cooperativity in the NMDA receptor. Neuron. 32:1085–1096. 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00539-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmund C., Stern-Bach Y., Stevens C.F.. 1998. The tetrameric structure of a glutamate receptor channel. Science. 280:1596–1599. 10.1126/science.280.5369.1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorge S., Elenes S., Colquhoun D.. 2005. Maximum likelihood fitting of single channel NMDA activity with a mechanism composed of independent dimers of subunits. J. Physiol. 569:395–418. 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.095349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T.C., Howe J.R.. 2000. Concentration-dependent substate behavior of native AMPA receptors. Nat. Neurosci. 3:992–997. 10.1038/79931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobolevsky A.I., Beck C., Wollmuth L.P.. 2002. Molecular rearrangements of the extracellular vestibule in NMDAR channels during gating. Neuron. 33:75–85. 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00560-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobolevsky A.I., Prodromou M.L., Yelshansky M.V., Wollmuth L.P.. 2007. Subunit-specific contribution of pore-forming domains to NMDA receptor channel structure and gating. J. Gen. Physiol. 129:509–525. 10.1085/jgp.200609718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobolevsky A.I., Rosconi M.P., Gouaux E.. 2009. X-ray structure, symmetry and mechanism of an AMPA-subtype glutamate receptor. Nature. 462:745–756. 10.1038/nature08624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebel D., Carvalho S., Paoletti P.. 2011. Functional evidence for a twisted conformation of the NMDA receptor GluN2A subunit N-terminal domain. Neuropharmacology. 60:151–158. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynelis S.F., Wollmuth L.P., McBain C.J., Menniti F.S., Vance K.M., Ogden K.K., Hansen K.B., Yuan H., Myers S.J., Dingledine R.. 2010. Glutamate receptor ion channels: structure, regulation, and function. Pharmacol. Rev. 62:405–496. 10.1124/pr.109.002451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wo Z.G., Oswald R.E.. 1995. Unraveling the modular design of glutamate-gated ion channels. Trends Neurosci. 18:161–168. 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93895-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood M.W., VanDongen H.M., VanDongen A.M.. 1995. Structural conservation of ion conduction pathways in K channels and glutamate receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:4882–4886. 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyllie D.J., Béhé P., Nassar M., Schoepfer R., Colquhoun D.. 1996. Single-channel currents from recombinant NMDA NR1a/NR2D receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Proc. Biol. Sci. 263:1079–1086. 10.1098/rspb.1996.0159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan H., Erreger K., Dravid S.M., Traynelis S.F.. 2005. Conserved structural and functional control of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor gating by transmembrane domain M3. J. Biol. Chem. 280:29708–29716. 10.1074/jbc.M414215200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]