Abstract

Background: The interdisciplinary surgery block of the reformed undergraduate curriculum HeiCuMed includes daily cycles of interactive case-based seminars, problem-based tutorials, case presentation by students, skills and communication training, and bedside teaching. The teaching doctors receive didactic training. In contrast, the previous traditional course was based on lectures with only two weekly hours of bedside teaching. Didactic training was not available.

Objective: The present work aims at analysing the importance of active participation of students and the didactic components of the reformed and traditional curricula, which contribute to successful learning as evaluated by the students.

Method: Differentiated student evaluations of the undergraduate surgical courses between 1999 and 2008 were examined by correlation and regression analyses.

Results: The evaluation scores for organisation, dedication of the teaching staff, their ability to make lessons interesting and complex topics easily understandable, and the subjective gain of knowledge were significantly better in HeiCuMed than in the traditional curriculum. However, the dependence of knowledge gain on the didactic quality was the same in both curricula. The quality of discussions and the ability of the teaching doctors to promote active student participation were important to the subjective gain of knowledge in both seminars and practical courses of the reformed curriculum as well as for the overall evaluation of the practical courses but not the gain of knowledge in the traditional curriculum.

Conclusion: The findings confirm psychological-educational perceptions, that competent implementation of integrative didactical methods is more important to successful teaching and the subjective gain of knowledge than knowledge transfer by traditional classroom teaching.

Keywords: Medical education, reform curriculum, sugery, didactics

Abstract

Hintergrund: Der interdisziplinäre Chirurgische Block des Heidelberger Reformcurriculums HeiCuMed beinhaltet interaktive, fallbasierte Kleingruppenseminare, Fertigkeiten- und Kommunikationstraining, Problem-orientiertes Lernen, studentische Fallbearbeitungen und -präsentationen sowie Unterricht am Krankenbett. Die Dozenten werden didaktisch geschult. Das vorangegangene traditionelle Curriculum basierte dagegen auf Vorlesungen und lediglich zwei Wochenstunden praktischen Unterrichts am Krankenbett.

Ziel: Die vorliegende Arbeit analysiert den Beitrag didaktischer Merkmale des traditionellen und Reformcurriculums sowie der aktiven Mitarbeit der Studierenden zum Lernerfolg aus Sicht der Studierenden.

Methode: Differenzierte studentische Evaluationen der chirurgischen Lehrveranstaltungen zwischen 1999 and 2008 wurden mittels Korrelations- und Regressionsanalysen untersucht.

Ergebnisse: Das Engagement der Dozenten, ihre Fähigkeit, Interesse zu wecken und Kompliziertes verständlich zu erklären, der Beitrag des Unterrichts zum Lernzuwachs, die Unterrichtsqualität und besonders die geförderte Mitarbeit wurden in HeiCuMed signifikant besser bewertet als im traditionellen Curriculum. Die Abhängigkeit des subjektiven Lernzuwachses von der didaktischen Qualität war hingegen in beiden Curricula gleich. Die geförderte studentische Mitarbeit erwies sich als wichtig für den subjektiven Lernzuwachs in den Seminaren und Praktika von HeiCuMed und für die evaluierte Qualität der Praktika aber nicht für den Lernzuwachs im traditionellen Curriculum.

Schlussfolgerung: Die Ergebnisse stehen im Einklang mit psychologisch-pädagogischen Erkenntnissen, dass integrative Lehrmethoden mehr zum Lehr- und Lernerfolg beitragen als der passive Wissenstransfer durch die traditionelle Vorlesung, und belegen die wichtige Bedeutung der didaktischen Kompetenz für den Lehrerfolg.

Introduction

Due to specialisation in modern medicine and, at the same time, interdisciplinary networking of different disciplines, detailed instruction of the various diagnostic and therapeutic measures within the scope of the undergraduate medical course has become nearly impossible. Medical schools can only give the students a basis for lifelong learning [1], [2], so that teaching and professional development should be seen as a continuum. The development of independent learning skills, analytical thinking and an education-oriented culture of debate are increasingly gaining importance as the scaffold for independent lifelong learning and for planning interdisciplinary diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. To meet these requirements, medical degrees are changing in many places. Learner-oriented adult education methods, which actively integrate students into the educational process, are replacing traditional teacher-centred lectures. The cornerstones of modern medical education are:

Analytical, interactive learning in small groups. The medical teacher acts as process initiator and facilitator rather than as a content expert. Knowledge acquisition is based on self-directed learning [3], [4].

Problem-based (PBL) or evidence-based learning (EBL) aims to promote personal responsibility for the learning process, the critical use of sources of knowledge, teamwork, and cooperation [5], [6]. However, it is not certain that PBL increases knowledge acquisition in comparison with traditional teaching methods [7], [8].

Practical teaching with communication training supplements acquisition of theoretical knowledge. The spectrum of methods used ranges from e-learning or computer-based training (CBT) [9] including virtual patients [10] to a variety of simulation techniques [11], [12] in skills laboratories [13], role play [11], bedside teaching [14] and the use of trained actors, the so-called standardised patients [15].

In Germany, the use of modern educational methods in medicine slowly began in the late 1990s as part of model and reformed undergraduate courses at some universities [16], [17]. This development gained increasing support in 2002 through the revised Licensure Regulation for Doctors (ÄAppO) which granted medical schools freedom in the design of their curricula [18]. To date, nine medical schools have adopted reformed undergraduate courses and most other faculties have integrated modern teaching methods into their standard curricula [19], [20]. Most reform efforts are based on the integration of EBM and PBL into the curriculum [16], [21], [22], [23], [24]. Skills laboratories [19], [25] and the integration of standardised patients into skills and communication training [26] support teaching at many faculties

Didactics in reformed curricula

The reformed medical curriculum is based on the principles of adult learning [4], [27], [28], [29], [30] and requires active interaction between teachers and learners. While in the traditional curriculum a good medical teacher only needs to master the art of presenting, under reformed curricula they also need to be able to moderate learning processes flexibly and actively teach practical skills. The teaching methods that should be applied are based on the findings of modern psychological and educational research on the learning process and the needs of students [31]. However, there is little information on the success of modern teaching and its relevance to the learning process of students in the field of medical education. Although the advantages and disadvantages of the different teaching strategies have often been discussed in the literature, questions remain about what should be done in a medical education class to best promote the learning progress of the students.

Traditional and reformed surgical training in Heidelberg

Up until October 2001, traditional surgical training in Heidelberg consisted of two plenary sessions and weekly practical bedside sessions per year and cohort as well as a weekly lecture on differential diagnosis for one semester [32]. With the introduction of the reformed curriculum, the Heidelberg Curriculum Medicinale (Hei-CuMed) [17], [33] in 2001, undergraduate surgical training was radically re-structured. Since October 2001 it has been embedded into an interdisciplinary block lasting a full semester with 20-30 hours a week. The surgical block takes place with half a year cohort at a time in the first and second clinical semesters [34], [35]. The surgical block includes theme-based rotational modules with a daily cycle of cardinal symptoms based-seminars, problem-based tutorials (PBL), case presentations by students, skills training in skills laboratories, examination and communication skills with standardised patients and bedside teaching. The amount of traditional chalk and talk teaching was limited to a single daily cardinal symptoms-oriented lecture (see http://www.medizinische-fakultaet-hd.uni-heidelberg.de/Block-II-Chirurgie.110171.0.html). As observed by long-term evaluations, the small group seminars, PBL and in particular the clinical training under HeiCuMed consistently attract significantly higher approval among students compared to the lectures and practical training of the traditional curriculum [35]. The training for medical teaching staff which is mandatory for postdoctoral degrees [36], (see http://www.medizinische-fakultaet-hd.uni-heidelberg.de/108919.pdf?L=de) and the professionalisation of several medical teachers in the postgraduate course Master of Medical Education give the teaching staff the methodological and pedagogical competence in accordance with current educational and psychological research.

Goals of this study

The present study addresses the question of which approaches to teaching contribute to the success of modern medical training. It examines didactic aspects of teaching in the traditional and reformed surgical training from a student perspective. Special attention is paid to the importance of active participation of students for the subjective learning success and to their overall assessment of teaching.

To answer this question from the student perspective, we analysed differentiated evaluation data from 1999-2000 and 2006-2008. We examined the significance of the following aspects for the subjective learning progress and overall evaluation of the courses:

Organisation of courses,

Commitment of the Medical teaching staff

Ability of the medical teaching staff to explain complicated issues in a simple manner and to make their classes interesting,

Active involvement of students in theoretical and practical teaching sessions,

Frequency and productivity of classroom discussions.

Methods

Participants, evaluation instruments, data collection, and data protection

The study included 825 evaluation forms from 1999-2000 from the traditional curriculum and 4816 digital evaluations of HeiCuMed modules from 2006-2008, a time by which most medical teachers had completed training in didactics and when the evaluation of HeiCuMed had reached stability [35]. The age of the respondents was 24.2±2.04 (mean±SD) years of age in the traditional curriculum and 23.7±3.14 under HeiCuMed. 57% of the respondents from the traditional curriculum were in the 7th and 35% in the 8th Semester. With a few exceptions, the HeiCuMed respondents were nearly equally divided between the 6th and 7th semesters (exact figures were not documented). All evaluations were completed anonymously, so personal attribution of the data was not possible. To survey students of the traditional curriculum, the Heidelberg Inventory for Course Evaluation (HILVE I with 33 items [37]) or its abbreviated forms were used as described [35]. The texts of the items analysed here are given in the results section. Apart from some items as listed in the results section, the items analysed were the same in all instruments. The evaluations were carried out using a seven-point Likert scale with 1=highest and 7=worst grade of rating. Although not scientifically proven, in our experience students tend to assess teaching benevolently. Therefore their opinions were considered conservatively, with Grades 4-7 considered as negative, 2-3 as neutral and only Grade 1 as clearly positive. The overall assessment of courses was carried out using the “German school grading scale” from 1 (best) to 6 (worst).

Statistical methods

The evaluation data was tabulated in Microsoft Excel®. A two-tailed t-test for independent samples, calculation of Cohen’s d, Cronbach’s α, correlation and regression analyses were performed using Excel and SPSS®16. The correlation expresses the degree of the association between two items whereas regression (Model II) provides an estimation of the dependence of a criterion on the respective predictor [38]. Together they describe the relationship between predictor and criterion.

A z-test for equality of regression coefficients was performed according to reference [39]. For the correlation and regression analyses both the raw evaluation data and the mean evaluation values of the individual courses and modules were used. The reliability analysis of the evaluation data has already been described [35]. The application of mean evaluation values for the analysis of HILVE-I evaluation data has already been advocated on the basis of high inter-rater reliability and the consistency of aggregated HILVE-I data [37]. Graphics were generated in Excel® and processed using Canvas® (ACD Systems).

Results

Evaluation of teaching quality in the traditional curriculum and HeiCuMed

All questionnaires had the following items in common:

One item for evaluation of the organisation of courses or classes:

► “The course/events is/are well organised.”

Six items for evaluating the commitment and didactic skills of the medical teacher:

► “The teacher seems to be well prepared.”

► “The teacher shows dedication to teaching and tries to communicate enthusiasm.”

► “The teacher is able to make complicated content easy to understand.”

► “There are sufficient discussions.”

► “The discussions are productive.”

► “The course(s) was/were interesting.”

Two items for evaluating the contribution of the class to knowledge gain:

► “I gained important and meaningful knowledge.”

► “Participation in the course is beneficial.”

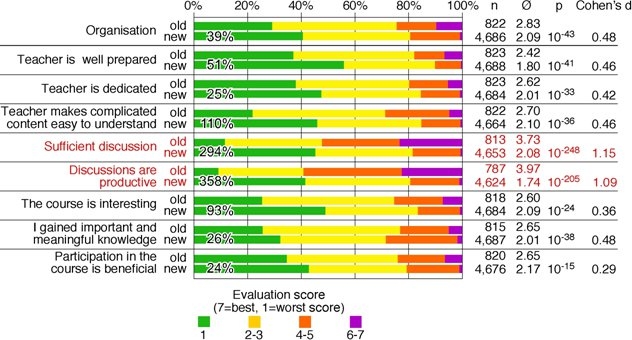

Course organisation, teacher commitment, the ability of the teachers to make complicated things understandable and to make the course interesting, and the contribution of the evaluated classes to learning progress were significantly better evaluated under HeiCuMed than under the previous traditional curriculum. The effect size ranged between Cohen’s d 0.36 and 0.48 (see Figure 1 (Fig. 1)). The proportion of very satisfied students (evaluation Grade 1, green in Figure 1 (Fig. 1)) in the assessment of these items increased under HeiCuMed by 25-110% as compared to the traditional curriculum. The difference between the assessment of the traditional and reformed curricula was particularly large with respect to the extent and quality of classroom discussions and had an effect size of 1.09 to 1.15. Under the traditional curriculum, the extent and productivity of the discussions received 52.3 to 59.2% negative evaluation grades (Grades 4-7, orange and purple in Figure 1 (Fig. 1)) and only 9.1 to 11.5% of the ratings were clearly positive (green in Figure 1 (Fig. 1)). In contrast, under HeiCuMed the proportion of the very positive evaluations of the discussions was 41.5 to 45.3% and only 18.5 to 19.4% of the evaluations were negative (see Figure 1 (Fig. 1)).

Figure 1. Stacked bar chart of the proportional distribution of evaluation scores given for the items specified in the traditional (old) and reformed curriculum (new). (n) Number of the corresponding item evaluations; (Ø) mean, (p) probability of equivalence of means by t-test; (Teacher) medical teacher.

42.8% of the evaluating students from HeiCuMed and 34.7% from the traditional curriculum expressed by using the highest rating grade that taking part in the teaching events was worthwhile (see Figure 1 (Fig. 1)). Under HeiCuMed, neutral and negative scores for this evaluation criterion were often accompanied by free text explaining that the issues discussed had already been covered elsewhere [35].

Gender differentiation

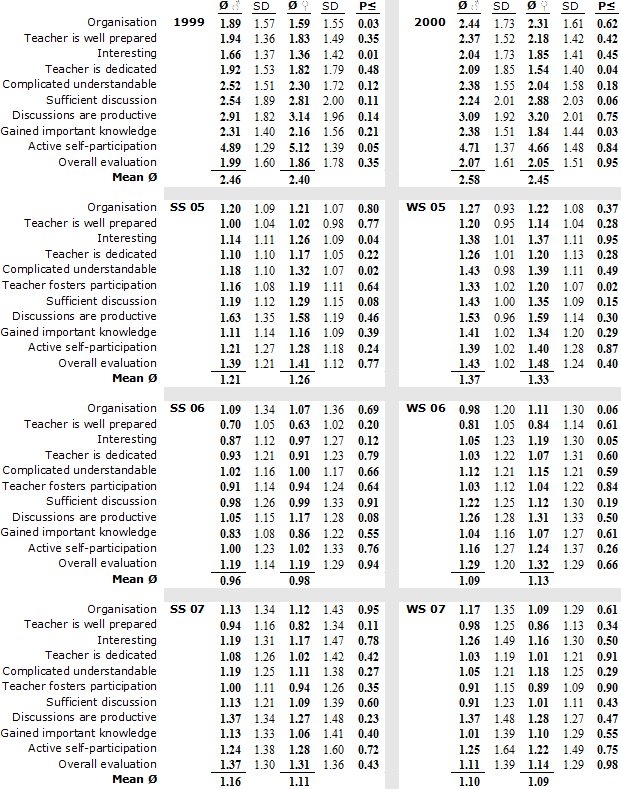

The gender distribution of the respondents ranged between 52.2%:47.8% and 49.4%:50.6% (♂:♀) under the traditional curriculum and from 48.9%:51.1% to 31.4%:68.6% under the reformed curriculum. To determine whether the gender distribution had an impact on the evaluation results, the evaluation data of the female and male respondents were compared (see Table 1 (Tab. 1)). The differences usually only amounted to a few hundredths of an evaluation point, were significantly smaller than the differences between the semesters and curricula, balanced themselves out in every semester and in 72 of 80 analysed cases were not significantly different. The evaluation data of both sexes were therefore pooled for subsequent analysis.

Table 1. A comparison between the evaluation scores of male and female respondents. (Ø) Mean; (SD) standard deviation; (p) error probability by t-test; (Teacher) medical teacher; (Interesting) “The course(s) was/were interesting“; (Complicated) “The teacher makes complicated content easy to understand” (Discussion) “There were sufficient classroom discussions”; (Productive) “The discussions were productive”.

Relationship between the educational items and the subjective learning progress as well as the overall assessment of the courses

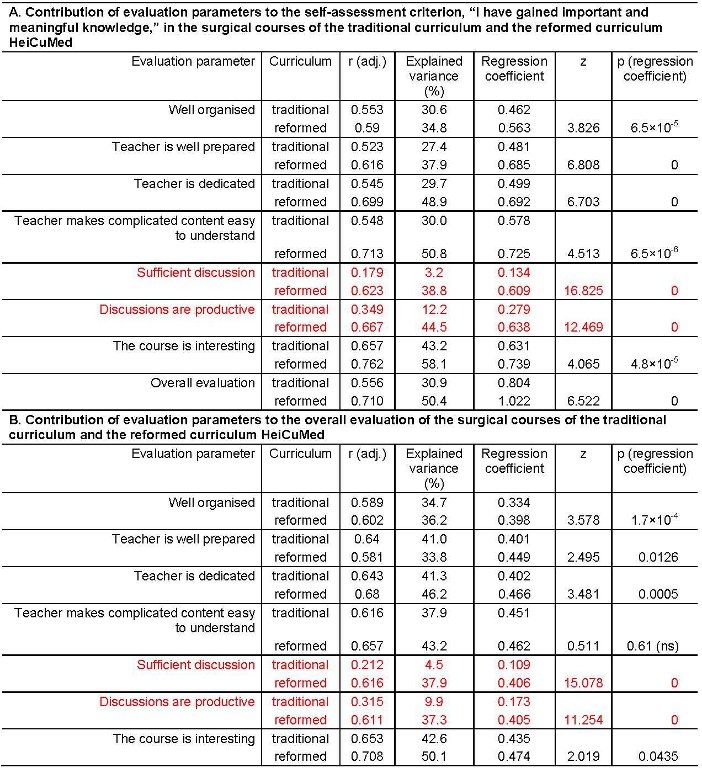

Correlation and regression analyses were carried out to analyse the possible link between the didactic characteristics examined as predictors and the perceived contribution of the courses to knowledge gain and to the overall evaluation of the courses as criteria. The relationship between predictor and criterion was assessed by the correlation coefficient r and the slope a of the regression line (regression coefficient a). Cronbach’s α for the items of the traditional and the reformed curricula was 0.891 and 0.946, respectively.

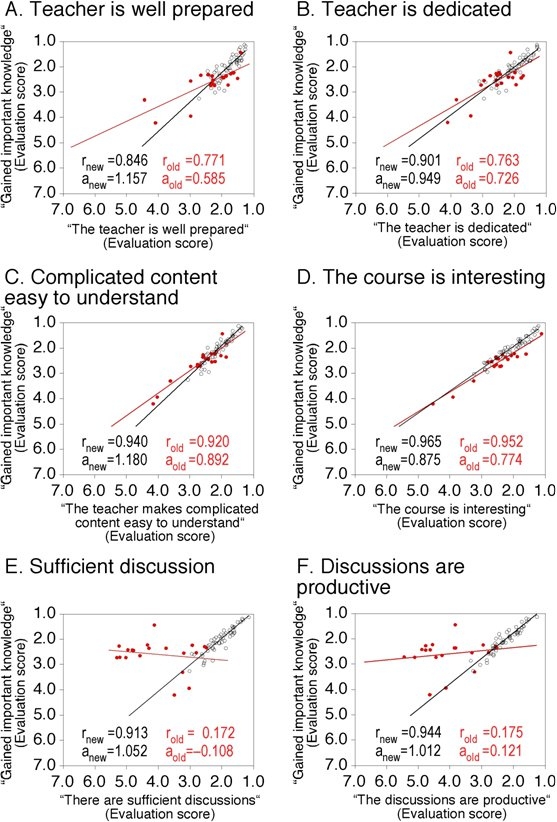

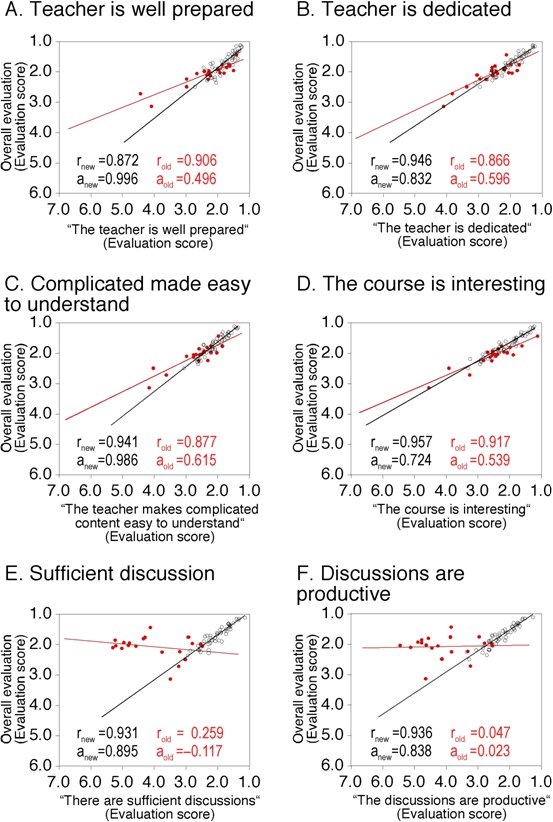

The assessment of course organisation, preparation and commitment of the medical teachers, their ability to explain complicated issues in a simple fashion and to make the lessons interesting correlated strongly with the assessment of the contribution of classes to knowledge gain in both curricula (see Table 2A (Tab. 2) and Figure 2A-2D (Fig. 2)) and with the overall rating of classes (see Table 2B (Tab. 2) and Figure 3A-3D (Fig. 3)). The correlations between the assessment of the predictors “the teacher is dedicated,” “the teacher is able to make complicated content easy to understand” or “the course was interesting” and the evaluation of the criterion “I gained important and meaningful knowledge” were similar in the two curricula (see Figure 2B-2D (Fig. 2)).

Table 2. Correlation and regression analysis of course evaluation. The correlation between the evaluation scores of the specified predictors and criteria and the corresponding regression coefficients (a) calculated for 825 evaluations of the traditional curriculum and 4816 evaluations of the modules of the reformed curriculum. The corresponding regression coefficients of the two curricula were tested for equality by z-test. (Explained variance) Proportion of the variance of the criterion explained by the predictor in the corresponding bivariate distribution; (r (adj.)) adjusted correlation coefficient; (z) z-statistic; (p) probability of the equality of the regression coefficients; (ns) not significant.

Figure 2. The relationship between the subjective knowledge gain (“Gained important knowledge”) and the items relating to didactics in the traditional and the reformed curriculum HeiCuMed. The scatter plots represent the bivariate distribution of the evaluation means of the specified items in the traditional curriculum (20 points, red) and HeiCuMed modules (50 points, black). The corresponding extrapolated regression lines, regression coefficients (a) and adjusted correlation coefficients (r) for the traditional curriculum (old) and HeiCuMed (new) are given in the corresponding colours.

Figure 3. The relationship between the evaluated quality of and the items relating to didactics in the traditional and the reformed curriculum HeiCuMed. The scatter plots represent the bivariate distribution of the evaluation means of the specified items in the traditional curriculum (20 points, red) and HeiCuMed modules (50 points, black). The corresponding extrapolated regression lines, regression coefficients (a) and adjusted correlation coefficients (r) for the traditional curriculum (old) and HeiCuMed (new) are given in the corresponding colours.

In both curricula the strongest criterion-predictor relationship was between the self-assessment of knowledge gain and the assessment of the ability of the teachers to communicate complicated issues comprehensibly as well as their ability to make the lessons interesting (see Table 2A (Tab. 2) and Figures 2C, 2D (Fig. 2)).

There was also strong relation between the evaluation of the preparedness of the teaching staff and the criterion, “I gained important and meaningful knowledge.” However, this was stronger under HeiCuMed than in the traditional curriculum (see Table 2A (Tab. 2) and Figure 2A, 2B (Fig. 2)).

In contrast to these similarities, the students of the traditional and reformed curricula differed substantially in their assessment of the importance of classroom discussions for knowledge gain and for the overall quality of the classes or lectures. Under HeiCuMed, there is very high correlation between the predictor “Sufficient discussion” and the criteria “I gained important and meaningful knowledge” and overall evaluation, as well as between the predictor “The discussions are productive” and the same criteria. Furthermore, the corresponding linear regressions point to a linear dependency of subjective knowledge gain and the perceived overall quality of teaching on the frequency and productivity of classroom discussions (see Table 2A (Tab. 2), Figure 2E, 2F (Fig. 2) and Figure 3E, 3F (Fig. 3)). Conversely, the evaluation data from the traditional curriculum did not reveal a relationship between the assessment of classroom discussions and the assessment of knowledge gain or the overall evaluation (see Table 2A (Tab. 2), Figure 2E, 2F (Fig. 2) and Figure 3E, 3F (Fig. 3)).

The importance of active participation for the learning process in the traditional and reformed curricula

The discrepancy between the traditional and reformed curricula regarding the relationship between the subjective knowledge gain and both the evaluation of the classroom discussion and of the overall quality of the courses indicates that students of both curricula weighted the importance of their active participation for successful learning differently. To investigate this possibility more closely, additional items were included in the analysis, which reflect the students’ classroom participation. Since the different evaluation instruments had no further items on this topic in common, related items were examined. Also, with regard to the different nature of the theoretical and practical teaching, the evaluations of the lectures and practical sessions in the traditional curriculum versus the seminars and practical sessions under HeiCuMed were analysed separately.

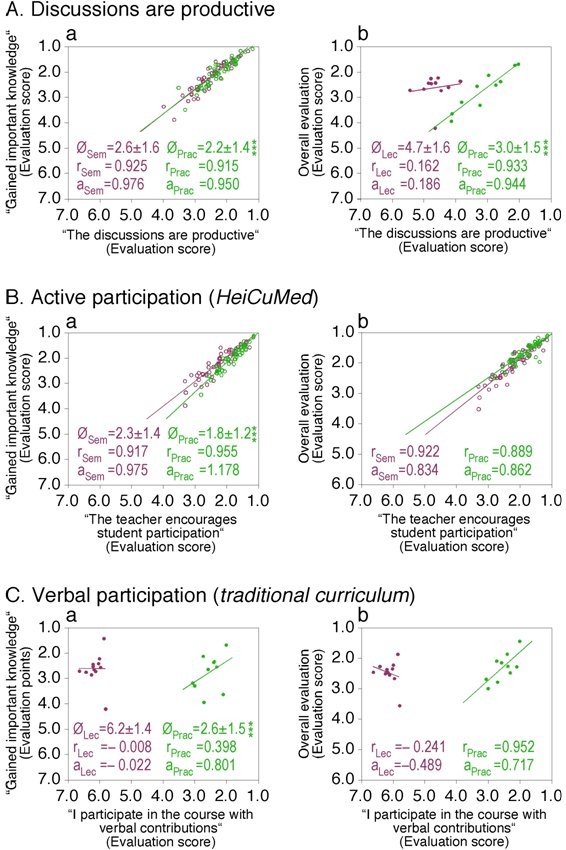

The average rating of the items that reflected active participation of students in practical sessions and lectures or seminars was lower in the traditional curriculum than under HeiCuMed (see Figure 4Aa, 4Ab, 4Ba, 4Ca (Fig. 4)). Furthermore, the average rating of both these items was better for the practical sessions than for the lectures or seminars in both curricula. This includes the items “The discussions are productive” (see Figure 4Aa, 4Ab (Fig. 4)), “The teacher fosters participation” (under HeiCuMed, Fig 4Ba) and “I participate with verbal contributions” (in the traditional curriculum, see Figure 4Ca (Fig. 4)). The differences between the assessment of active participation in lectures or seminars and in practical sessions in the traditional curriculum were significantly bigger than under HeiCuMed (see Figure 4Aa vs. 4Ab and 4Ba vs. 4Ca (Fig. 4)).

Figure 4. The relationship between the subjective knowledge gain or the overall evaluated quality of courses and participation-related items in theoretical and practical teaching in the traditional curriculum and the reformed curriculum HeiCuMed. The scatter plots represent the bivariate distribution of the evaluation means of the specified item in the module seminars (purple rings) and practical sessions (green rings) under HeiCuMed and in the lectures (purple dots) and practical sessions (green dots) of the traditional curriculum. The means and standard deviations of the predictor evaluations (Ø) and the corresponding regression line, regression coefficients (a) and adjusted correlation coefficients (r) are given in the corresponding colours. The predictors (x-axis) and their average values in Ba and Bb, Ca and Cb are the same. (Sem) Seminar, (Pract) practical session, (Lect) lecture, (***) p≤0.001.

To gain an insight into the relationship between classroom participation and the quality of teaching, correlation and regression analyses were performed. The relationship between the predictor “The discussions are productive,” and the criterion “I gained important and meaningful knowledge” in the evaluation of the seminars (purple in Figure 4Aa (Fig. 4), r=0.925, a=0.976) and the practical sessions (green in Figure 4Aa (Fig. 4), r=0.915, a=0.950) under HeiCuMed was strong and almost identical. The slope of the regression curve of a~1 suggests that changes in knowledge gain are linked to comparable changes in the productivity of the discussions. A similar relationship between these items also occurred in the evaluation of the practical sessions (green in Figure 4Ab (Fig. 4), r=0.933, a=0.944) but not of the lectures (purple in Figure 4Ab (Fig. 4), r=0.162, a=0.186) of the traditional curriculum.

A high correlation also exists in HeiCuMed between the evaluation of participation fostering by the teaching staff and the evaluation of the students’ own knowledge gain (see Figure 4Ba (Fig. 4)) and the overall rating (see Figure 4Bb (Fig. 4)) of the seminars (r=0.917/0.922, a=0.975/0.834) and practical training (r=0.955/0.889, a=1.175/0.862).

The item “I participate with verbal contributions” was used as a comparable measure of classroom participation in the traditional curriculum. The assessment of this item and its relationship with knowledge gain (see Figure 4Ca (Fig. 4)) and the overall evaluation (see Figure 4Cb (Fig. 4)) show noticeable discrepancies between the evaluation of lectures (r=-0,008/-0.241, a=-0.022/-0.489) and practical sessions (r=0.398/0.952, a=0.801/0.717). In the evaluation of the lectures most group means appear to be a tight bundle showing little variability. All mean evaluation results (6.2±1.4 mean±SD) reflect an almost complete absence of active student participation in lectures (purple in Figure 4Ca, 4Cb (Fig. 4)). Much better participation (2.6±1.5) was revealed by the evaluation of these items in the practical sessions of the traditional curriculum (green in Figure 4Ca, 4Cb (Fig. 4)). The different evaluation results in the traditional curriculum mirror the passive participation of students in lectures and their active participation in bedside teaching and support the reliability of the students’ statements.

Curiously in the practical sessions of the traditional curriculum the correlation between active participation and perceived learning success (green in Figure 4Ca (Fig. 4)) was weaker than the correlation between participation and the overall assessment of the sessions (green in Figure 4Cb (Fig. 4)). The latter was similar to the relationship between comparable items under HeiCuMed.

Discussion

HeiCuMed is one of several medical reform curricula which aim to improve the quality of undergraduate medical education through improved teaching and by fostering active participation of the students. The aim is to go beyond the pure acquisition of knowledge and impart practical skills and professional competences which will prepare the graduates for lifelong learning and the application of acquired knowledge within the framework of a modern interdisciplinary healthcare system. Aldready during the introductory phase of the reforms, different universities reported high student satisfaction with the innovative changes in their respective courses [8], [12], [23], [24], [25], [40], [41], [42], [43]. In Heidelberg too the courses of the reformed curriculum are consistently rated better by the students than those of the traditional curriculum [34], [35].

The present study investigates to what extent the objective of promoting active participation of students has been achieved. It further investigates the impact the new teaching strategy and active classroom participation have had on teaching quality and subjective learning success from the perspective of the students. The study is based on an inductive process due to the lack of similar studies and in order to develop appropriate hypotheses. It is not so much intended to give solid answers but rather to raise issues that future research should explore in more detail.

The analysis of the research questions was limited by the disadvantage, that the available data had come from student evaluations. They had not been primarily designed for the present research purposes but rather constituted a measure of quality control. Some conclusions therefore had to be inferred from related items. However, the evaluation instrument employed had been thoroughly studied and validated [37], justifying its use in the present analysis. With few changes, it has been used continuously since 1999, a period that straddles both the traditional curriculum and HeiCuMed, allowing the comparison between the two curricula.

Teaching and learning under the reformed curriculum

Self-directed learning is a major aspect of HeiCuMed and should be supported by the course. This requires different skills than in a traditional teacher-centred curriculum, both from the teaching staff and the learners. It also requires a new attitude to learning and teaching. The students, who acquired quite different learning techniques during their school time, are confronted with the need to adapt to new learning strategies.

Improving the quality of education by reforming teaching

The evaluation of different teaching characteristics showed a significant higher satisfaction amongst students in HeiCuMed compared to the traditional curriculum. This allows the conclusion that the reformed curriculum is widely accepted by the students. It is interesting in as much as the traditional curriculum was taught by a few, highly experienced medical teachers while HeiCuMed involves a large number of teachers, partly with little experience. The likely explanation for this lies in the changes to the organisational and didactic concept of the reform curriculum and the training of its medical teachers [35].

Increasing active participation in reformed teaching

In comparison to the traditional curriculum the increase in the rating of items that pertain to the promotion and extent of active student participation in HeiCuMed classes was particularly pronounced. In the traditional curriculum discussions were rare and their productivity received noticeably negative ratings by the students. HeiCuMed students rated the frequency and productivity of the discussions with a high effect size as substantially better. The evaluation of the promotion of student participation by the teachers as well as the self-assessment of the students’ own oral participation also show that from the students’ perspective the reformed curriculum meets the purpose of promoting their active participation in the educational process. However, it is currently not known whether different expectations of the students of both curricula influence their evaluation. A recently initiated study on motivation aims to clarify the relationship between expectations and subjectively experienced reality.

Correlation and regressions analyses

The evaluation of a course or of a medical teacher expresses the degree of student satisfaction and not necessarily the contribution of the evaluated characteristics to the learning process. To investigate this relationship, correlation and regression analyses were performed.

The evaluated predictors had very high Cronbach’s α values and thus showed a remarkably strong inter-item correlation. The possibility that the evaluated items covered similar information can therefore not be excluded. On the other hand, it is conceivable that the strong inter-correlation points to links between the indicators of teacher quality. In part this can be explained by the fact that in each questionnaire the various items were not independent from one another but simultaneously assessed the same teachers and class or lecture. In addition, it is likely that students make less differentiated judgements than theoretically expected.

The relationship between didactic characteristics, the quality of teaching, and the subjective learning success

As indicated by the regression coefficients, the perceived knowledge gain and the perceived quality of teaching similarly depended in both curricula on the evaluated conditions (organisation) and didactic indicators (teacher was prepared and dedicated, makes complicated content easy to understand, interesting class). This suggests that the success of a course is similarly linked in either curriculum to the quality of the organisation and of the didactic skills of the teachers. According to the low dispersion of the bivariates, the ability of teachers to explain complex issues in an understandable fashion was of special importance to the perceived knowledge gain and overall satisfaction. Almost as important was the ability of the teaching staff to present the material in interesting ways.

The correlation between the subjective knowledge gain or the assessed overall quality and the didactic predictors was strong, with r>0.5, in both curricula. It was striking, however, that in the analysis of the raw data of the traditional curriculum the evaluation of knowledge gain correlated less well with the didactic predictors than with the overall evaluation of the course. In contrast, under He-iCuMed both criteria, knowledge gain and overall quality, correlated similarly well with the teaching predictors. This finding suggests that in the reformed curriculum the teaching skills of medical teachers are just as important for the perceived knowledge gain as they are for the satisfaction with the classes. In contrast, the didactic skills of the teachers in the traditional curriculum appear to be less important for knowledge gain compared to the perceived quality of the lectures. Consistent with this interpretation, the subjective knowledge gain under HeiCuMed correlated more strongly with the overall quality of teaching than in the traditional curriculum.

Satisfaction versus demand

The average rating of the didactic items, the knowledge gain and the overall quality of the courses was significantly worse in the traditional curriculum than in the reformed curriculum. Nevertheless, the correlation and regression coefficients of the bivariate analyses of these items were similar in both curricula. This phenomenon was particularly evident in the analysis of the aggregated ratings of the items “The teacher is able to make complicated content easy to understand” and “The course was interesting”. Both items were rated significantly worse in the traditional curriculum compared to HeiCuMed. However, bivariate analysis revealed that their relationship to subjective knowledge gain and overall satisfaction was almost the same as in HeiCuMed. This suggests that the commitment of the medical teaching staff, their skills in explaining and the ability to make lessons interesting was equally important for students of both curricula and that the teaching staff of the reformed curriculum performed better in these respects. They therefore received better ratings. In other words, the desire of students to be taught by competent medical teachers was the same in both curricula but their satisfaction with the classes on offer seemed to vary in accordance with the teaching skills of the staff. Since the main differences between the medical teachers of both curricula are that the teachers of the reformed curriculum work under improved conditions, for example in small groups, and that most of them had received didactic training, it can be speculated that teacher training and the altered teaching conditions are partly responsible for the better results under HeiCuMed compared to the traditional curriculum.

Lectures and seminars versus practical sessions: Differential role of participation in the traditional and the reformed curriculum

The predictors discussed above relate to the personal skills of the medical teachers. The frequency and quality of classroom discussions, supporting student participation and self assessed oral participation also reflect their didactic skills because they are stimulated and moderated by the teachers. They are, however, primarily characteristics of active student participation in the learning process. At the same time they represent programmatic components of the modern teaching strategy. This underlines the importance of combining the reformed teaching strategy with a learning environment that promotes communication in small groups between teaching staff and students as well as among the students while also supporting independent learning and stimulating interest through group work and integrated hands-on training.

In both curricula the items which relate to active participation were better evaluated in practical sessions than in lectures (traditional curriculum) or seminars (HeiCuMed) but overall much worse in the traditional curriculum than under HeiCuMed.

The self-assessment of oral participation in practical sessions of the traditional curriculum correlated strongly with the overall evaluation but only weakly with the self-assessment of knowledge gains. This supports the assumption already discussed that in the traditional curriculum the impression of the quality of a course is related more strongly to form and content than to the perception of knowledge gain. One possible explanation for this is that in the traditional curriculum knowledge gain in lectures and the limited amount of bedside teaching (practical sessions) was subordinate to classroom-independent learning using textbooks and old examinations.

The lack of participation in lectures and active participation in practical sessions in the traditional curriculum are to be expected. In contrast to the traditional curriculum, in the reformed curriculum even theoretical knowledge transfer relies on active student participation. Furthermore, the finding that in HeiCuMed both overall satisfaction and the perception of knowledge gain equally benefit from fostered participation demonstrates the importance of replacing talk and chalk lectures by small group seminars which allow for and promote an active learning process.

Conclusions

The present results suggest that both the didactic skills of teachers and the interactive teaching strategy significantly affect the quality of reformed teaching and subjective knowledge gain. Furthermore, the results show that the didactic skills which are taught to the teaching staff of HeiCuMed significantly support the positive effects of the curriculum.

Outlook

The findings described here show that student satisfaction varies in each curriculum and that about 20% of the students have a more or less negative opinion even of the reformed curriculum. The follow-up study already mentioned above aims to illuminate the factors that influence motivation, study effort and success. It will include analyses of learning strategies, attitudes to studying, biographical characteristics, and secondary activities. These findings will be analysed in relation to success in the preclinical section of the medical licensure examination. In parallel an analysis of teaching behaviour and student learning behaviour is planned both through surveys and through classroom observation to enable a differentiated exploration of the contribution of teaching, organisational measures and student self-motivation to success in studying. A comparison between the course evaluations and the actual learning success in these courses is also planned pending yet unresolved ethical questions.

Thanks

The authors are indebted to the psychologists Gerald Wibbecke and Janine Kahmann for critically checking the manuscript, productive discussions and stimulating recommendations.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Hamdorf JM, Hall JC. The development of undergraduate curricula in surgery: I. General issues. ANZ J Surg. 2001;71:46–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.2001.02029.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1622.2001.02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agha RA, Papanikitas A, Baum M, Benjamin IS. The teaching of surgery in the undergraduate curriculum - reforms and results. Int J Surg. 2005;3:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2005.03.017. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stagnaro-Green A. Applying adult learning principles to medical education in the United States. Med Teach. 2004;26(1):79–85. doi: 10.1080/01421590310001642957. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590310001642957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLean M, Gibbs T. Twelve Tipps to designing and implementing a learner-centred curriculum: Prevention is better than cure. Med Teach. 2010;32(3):225–230. doi: 10.3109/01421591003621663. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/01421591003621663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wood DF. ABC of learning and teaching in medicine. Problem based learning. BMJ. 2003;326(8 Feb):328–330. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7384.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kahlke W, Kaie A, Kaiser H, Kratzert R, Schöne A, Kirchner V, Deppert K. Problemorientiertes Lernen: Eine Chance für die Fakultäten. Dt Ärztebl. 2000;97(36):A2296–A2300. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartling L, Spooner C, Tjosvold L, Oswald A. Problem-based learning in pre-clinical medical education: 22 years of outcome research. Med Teach. 2010;32(1):28–35. doi: 10.3109/01421590903200789. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/01421590903200789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Distlehorst LH, Dawson BK, Klamen DL. Supervisor and self-ratings of graduates from a medical school with problem-based learning and standard curriculum track. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(4):291–298. doi: 10.1080/10401330903228364. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10401330903228364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choules AP. The use of elearning in medical education: a review of the current situation. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:212–216. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.054189. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2006.054189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang G, Reynolds R, Candler C. Virtual patient simulation at U.S. and Canadian medical schools. Acad Med. 2007;82(5):446–451. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803e8a0a. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803e8a0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lane JL, Slavin S, Ziv A. Simulation in medical education: A Review. Sim Gam. 2001;32:297–314. doi: 10.1177/104687810103200302. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/104687810103200302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziv A, Wolpe PR, Small SD, Glick S. Simulation-based medical education: an ethical imperative. Acad Med. 2003;78(8):783–788. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200308000-00006. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200308000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynagh M, Burton R, Sanson-Fisher R. A systematic review of medical skills laboratory training: where to from here. Med Educ. 2007;41(9):879–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02821.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramani S. Twelve Tipps to improve bedside teaching. Med Teach. 2003;25(2):112–115. doi: 10.1080/0142159031000092463. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0142159031000092463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.May W, Park JH, Lee JP. A ten-year review of the literature on the use of standardized patients in teaching and learning: 1996-2005. Med Teach. 2009;31(6):487–492. doi: 10.1080/01421590802530898. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590802530898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richter EA. Reformstudiengänge Medizin. Mehr Praxis, weniger Multiple Choice. Dt Ärztebl. 2001;98(31-32):2020–2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steiner T, Jünger J, Schmidt J, Bardenheuer H, Kirschfink M, Kadmon M, Schneider G, Seller H, Sonntag HG. Heicumed: Heidelberger Curriculum Medicinale - ein modularer Reformstudiengang zur Umsetzung der neuen Approbationsordnung. Gesundheitswesen (Suppl Med Ausbild) 2003;20(Suppl2):87–91. Available from: http://gesellschaft-medizinische-ausbildung.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=451&Itemid=649&lang=de. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haage H. Ausbildung zum Arzt: Was ist erreicht, was bleibt zu tun? Bundesgesundheitsbl. 2006;49(4):325–329. doi: 10.1007/s00103-006-1237-4. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00103-006-1237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kruppa E, Jünger J, Nikendei C. Einsatz innovativer Lern- und Prüfungsmethoden an den Medizinischen Fakultäten der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Eine aktuelle Bestandsaufnahme. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2009;134(8):371–372. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1124008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stifterverband für die Deutsche Wissenschaft. Quo vadis medice? Neue Wege in der Medizinerausbildung in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz. Essen: Stifterverband für die Deutsche Wissenschaft; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dahlmann C. Modellstudiengänge Medizin. Reformierte Curricula an einigen deutschen Unis. Stuttgart: Via medici online; 2005. (abgerufen Mai 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beyer M, Bergold M, Donner-Banzhoff N, Falk-Ytter Y, Gensichen J, Gerlach FM, Koneczny N, Legelmann M, Lühmann D, Ochsendorf F, Schulze J, Weberschock T. Evidenzbasierte Medizin im Studium. Frankfurt: Deutsches Netzwerk Evidenzbasierte Medizin eV.; 2003. Available from: http://www.ebm-netzwerk.de/grundlagen/grundlagen/images/curriculum_ebm_im_studium.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koneczny N, Hick C, Siebachmayer M, Floer B, Vollmar HC, Butzlaff M. Evidenzbasierte Medizin: Eingebettet in die Ausbildung - Selbstverständlich in der Praxis? Das integrierte EbM-Curriculum im Modellstudiengang Medizin der Universität Witten/Herdecke. Z ärztl Fortbild Qual Sich. 2003;97:295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Köllner V, Gahn G, Kallert T, Felber W, Reichmann H, Dieter P, Nitsche I, Joraschky P. Unterricht in Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie um Dresdner DIPOL-Curriculum. Der POL-Kurs „Nervensystem und Psyche". Psychother Psych Med. 2003;53:47–55. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-36965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fichtner A. Aufbau eines interdisziplinären Skills Lab an der Medizinischen Fakultät der TU-Dresden und Integration in das DIPOL(r)-Curriculum. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2010;27(1):Doc02. doi: 10.3205/zma000639. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/zma000639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fröhmel A, Burger W, Ortwein H. Einbindung von Simulationspatienten in das Studium der Humanmedizin in Deutschland. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2007;132(11):549–554. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-970375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaufman DM. ABC of learning and teaching in medicine. Applying educational theory in practice. BMJ. 2003;326(25 Jan):213–216. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norman GR, Schmidt HG. The psychological basis of problem-based learning: A review of the evidence. Acad Med. 1992;67(9):557–565. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199209000-00002. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merriam SB. Andragogy and self-directed learning: pillars of adult learning theory. New Direct Adult Cont Educ. 2001;89:3–14. doi: 10.1002/ace.3. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ace.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stagnaro-Green A. Applying adult learning principles to medical education in the United States. Med Teach. 2004;26(1):79–85. doi: 10.1080/01421590310001642957. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590310001642957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hattie J. Visible Learning. A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievemen. London, New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schürer S, Schellberg D, Schmidt J, Kallinowski F, Mehrabi A, Herfarth Ch, Büchler M, Kadmon M. Evaluation der traditionellen Ausbildung in der Chirurgie. Chirurg. 2006;77(4):352–359. doi: 10.1007/s00104-005-1123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huwendiek S, Kadmon M, Jünger J, Kirschfink M, Bosse HM, Resch F, Duelli R, Bardenheuer HJ, Sonntag HG, Steiner T. Umsetzung der deutschen Approbationsordnung 2002 im modularen Reformstudiengang Heidelberger Curriculum Medicinale (HeiCuMed) Z Hochschulentw. 2008;3(3):17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reimann K, Porsche M, Holler S, Kadmon M. Nachhaltigkeit einer verbesserten studentischen Evaluation im operativen Fachgebiet des Reformstudiengangs HeiCuMed: Vergleich zwischen traditionellem Curriculum und Reformcurriculum anhand halbstrukturierter Interviews von Studierenden im Praktischen Jahr. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2008;25(2):Doc81. Available from: http://www.egms.de/static/de/journals/zma/2008-25/zma000565.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kadmon G, Schmidt J, De Cono N, Kadmon M. Ein Modell zur nachhaltigen Qualitätssicherung der medizinischen Ausbildung am Beispiel des chirurgischen Reformcurriculums HeiCuMed. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2011;28(2):Doc29. doi: 10.3205/zma000741. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/zma000741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roos M, Kadmon M, Schulz J-H, Strittmatter-Haubold V, Steiner T. Studie zur Erfassung der Effektivität der HEICUMED Dozentenschulung - Effect of a 5-day Train-the-Trainer program in medical didactics. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2008;25(1):Doc12. Available from: http://www.egms.de/static/de/journals/zma/2008-25/zma000496.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rindermann H. Lehrevaluation. Einführung und Überblick zu Forschung und Praxis der Lehrveranstaltungsevaluation an Hochschulen mit einem Beitrag zur Evaluation computerbasierten Unterrichts. Landau: Verlag empirische Pädagogik; 2001. p. 142. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ. Biometry. The Principles and Practice of Statistics in Biological Research. New York: WH Freeman & Co.; 1982. pp. 454, 562–454, 565. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paternoster A, Brame R, Mazerolle P, Piquero A. Using the correct statistical test fort he equality of regression coefficients. Crim. 1998;36(4):859–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1998.tb01268.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1998.tb01268.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nikendei C, Kraus B, Schrauth M, Weyrich P, Zipfel S, Herzog W, Jünger J. Integration of role-playing into technical skills training: a randomized controlled trial. Med Teach. 2007;29(9):956–960. doi: 10.1080/01421590701601543. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590701601543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.König S, Markus PM, Becker H. Lehren und Lernen in der Chirurgie - das Göttinger Curriculum. Chirurg. 2001;72:613–620. doi: 10.1007/s001040170146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heye T, Kurz P, Eiers G, Kauffmann GW, Schipp A. Eine radiologische Fallsammlung mit interaktivem Charakter als neues Element in der studentischen Ausbildung. Fortschr Röntgenstr. 2008;180:337–344. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1027217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weller JM. Simulation in undergraduate medical education: bridging the gap between theory and practice. Med Educ. 2004;38(1):32–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2004.01739.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2004.01739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]