Abstract

GVL against chronic phase CML (CP-CML) is potent, but it is less efficacious against acute leukemias and blast crisis CML (BC-CML). The mechanisms underlying GVL-resistance are unknown. Previously, we found that alloreactive T cell targeting of GVL-sensitive bcr-abl-induced mouse CP-CML (mCP-CML) required TCR:MHC interactions and that multiple and redundant killing mechanisms were in play. To better understand why BC-CML is resistant to GVL, we performed a comprehensive analysis of GVL against mouse BC-CML (mBC-CML) induced by the retroviral transfer of the bcr-abl and NUP98/HOXA9 fusion cDNAs. Like human BC-CML, mBC-CML was GVL-resistant, and this was not due to accelerated kinetics or a greater leukemia burden. To study T cell recognition and killing mechanisms, we generated a panel of gene-deficient leukemias by transducing bone marrow from gene-deficient mice. T cell target recognition absolutely required that mBC-CML cells express MHC and GVL against both mCP-CML and mBC-CML required leukemia expression of ICAM-1. We hypothesized that mBC-CML would be resistant to some of the killing mechanisms sufficient to eliminate mCP-CML, but we found instead that the same mechanisms were effective against both types of leukemia as GVL was similar against wild type or mBC-CML genetically lacking Fas, TRAIL-R, Fas/TRAIL-R, TNFR1/R2 or when donor T cells were perforin−/−. However, mCP-CML but not mBC-CML, relied on expression of PD-ligands to resist T cell killing, as only GVL against mCP-CML was augmented when leukemias lacked PD-L1/L2. Thus, mBC-CML cells have cell-intrinsic mechanisms distinct from mCP-CML cells that protect them from T cell killing.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) can be a life-saving therapy for patients with hematologic malignancies. Much of the efficacy of alloSCT is due to an anti-tumor effect mediated by alloreactive donor T cells, called graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) (1, 2). GVL is extremely potent against chronic phase CML (CP-CML) wherein allograft T cell depletion increases the risk of relapse by 5–6 fold (3) and donor leukocyte infusions can induce remissions in approximately 80% of patients who have relapsed post-transplant (4). However, a variety of data support the idea that GVL is less efficacious against many other hematopoietic malignancies, including AML, ALL and CML that has progressed to blast crisis (blast crisis CML; BC-CML) (3–8). Patients with AML and ALL are typically transplanted in complete remission whereas CP-CML patients are transplanted with overt disease. Thus, differences in overall disease burden alone are unlikely to fully explain GVL-resistance.

Nonetheless, there clearly is a GVL effect against AML, ALL and BC-CML as the risks of relapse are decreased in patients with GVHD as compared to patients with none (3, 9, 10). Understanding why many neoplasms are as a group GVL-resistant and why GVL is effective in a subset of patients with these neoplasms are important first steps in developing approaches to render GVL-resistant cancers more GVL-sensitive.

A barrier in studying GVL-resistance has been the paucity of mouse leukemia models that share genetic etiology and phenotype with human leukemias and are inducible on different genetic backgrounds that will yield leukemias lacking critical molecules. In an effort to overcome these limitations we began by establishing a clinically-relevant model of a GVL-sensitive leukemia. We chose a murine model of CP-CML (mCP-CML) induced by the retroviral transduction of mouse bone marrow (BM) cells with a cDNA derived from the bcr-abl translocation, responsible for human CP-CML (11). mCP-CML is an oligoclonal myeloproliferative syndrome characterized by splenomegaly and a high WBC count with hematopoiesis dominated by maturing myeloid cells (12). An advantage of this model is that we are able to create leukemias lacking molecules that could be important for immunogenicity by infecting BM from gene-deficient mice (13–15). Key findings from our prior work on GVL against mCP-CML were that both CD4 and CD8 T cells must make direct TCR:MHC contacts with mCP-CML cells (13–15) and that T cells employ redundant effector mechanisms. Specifically, GVL was preserved when leukemias were Faslpr, TNFR1/R2−/−, TRAILR−/− and when T cells were perforin−/− and mCP-CML was Faslpr (13–15). We hypothesized that this redundancy at least in part accounted for GVL-sensitivity and that GVL-resistant diseases would be more reliant on single pathways.

To establish a GVL system against a GVL-resistant leukemia, we adopted a model of blast crisis CML (mBC-CML) induced by the cointroduction of the bcr-abl and the NUP98/HOXA9 (NH) fusion cDNAs (16). NUP98 is a nuclear pore protein that in AML is a fusion partner with at least 15 other genes, 8 of which encode Class 1 homeodomain proteins (such as HOXA9). Importantly, NH fusions have been reported in both AML and BC-CML (17–19). When NH alone is introduced by retrovirus into mouse BM cells, a clonal myeloblastic leukemia evolves with a long latency (20). However, when NH and p210 are cointroduced, a short-latency blast-crisis-like disease develops with hematopoiesis dominated by lineage-negative (lin−) myeloblasts (16, 21). Significant for our studies, gene-deficient mBC-CML can be induced by infecting BM from knockout mice.

Here we describe a comprehensive analysis of GVL against mBC-CML, including mechanisms of T cell recognition and killing and the roles of donor and recipient antigen presenting cells. We also test the roles of the inhibitory ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 and the adhesion molecule ICAM-1 on mBC and mCP-CML cells. As we found for GVL against mCP-CML, direct cognate interactions between T cells and mBC-CML cells were required. Contrary to our hypothesis and in disagreement with many studies evaluating GVL against leukemia cell lines (1), T cell killing mechanisms employed against mBC-CML were highly redundant. However, the absence of ICAM-1 on either mCP-CML or mBC-CML cells greatly reduced GVL. Surprisingly, although PD-L1/L2 on mCP-CML cells protected them from T cell killing, PD-L1/L2 on mBC-CML cells did not inhibit GVL, though PD-L1 was well expressed.

Materials and methods

Mice

Mice were between 7–10 weeks of age. B6 and BALB/c mice were obtained from the NCI (Frederick, MD). IAbβ−/− mice were purchased from Taconic (Germantown, NY). C3H.SW, B6 β2M−/− and Faslpr mice were purchased from the Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, MA). TNFR1/R2 −/− mice were created as described (13). TRAILR−/− and TRAILR+/+ littermates were a gift from Astar Winoto (22) (UCSF, San Francisco, CA). B6 perforin−/− mice were obtained from the Jackson Labs and crossed to B6bm12 mice (Jackson Labs) as described (14). PD-L1−/− and PD-L2−/− mice were provided by Lieping Chen (23) (Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT). PD-L1/L2 double deficient mice were kindly provided by Arlene Sharpe (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). ICAM-1−/− (intracellular adhesion molecule 1) mice (24) were purchased from the Jackson Labs.

Retrovirus production

MSCV2.2 expressing the human bcr-abl p210 cDNA and EGFP (M-p210/EGFP) or a non-signaling truncated form of the human low affinity nerve growth factor receptor (NGFR) driven by an internal ribosome entry site (M-p210/NGFR) were as described (13). MSCV2.2 expressing the NUP98/HOXA9 and EGFP downstream of the internal ribosome entry site (M-NH/EGFP) was a gift from D.G. Gilliland (Merck Research Labs, Whitehouse Station, NJ). Retroviral supernatants were generated as described (13, 25).

mCP-CML generation

p210-infected progenitors were generated as previously described (13). Briefly, On days −1 and 0 cells underwent “spin infection” with M-p210/NGFR or M-p210-EGFP retrovirus.

mBC-CML generation

To generate mBC-CML (Supplemental Figure 1), mice were injected on day −6 with 5mg 5-fluorouracil (5FU; Pharmacia & Upjohn, Kalamazoo Michigan). On day −2, BM cells were harvested and cultured in prestimulation media (DME, 15% FBS, IL-3 [6ng/ml], IL-6 [10ng/ml], and SCF [10ng/ml]; all cytokines from Peprotech; Rocky Hill, New Jersey). On days −1 and 0 cells were resuspended at 2×106/ml in prestimulation media with the addition of retroviral supernatants, polybrene (4ug/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and Hepes (100mm) (13). The final titer of M-NH/EGFP was that which infects 30% of 3T3 cells using our standard titering conditions and the titer of M-p210/NGFR was 2% of that. 7.5×105 cells that underwent spin infection were injected into 600cGy sublethally irradiated B6 hosts (primary mice; Supplemental Figure 1). Premorbid mice were sacrificed and splenocytes were frozen. These cells were passaged in sublethally irradiated mice, from which splenocytes were harvested and frozen (secondary mice). We then cloned mBC-CML cells by injecting 1000 live EGFP+ cells into sublethally irradiated hosts, which results in end-stage leukemia in 40–60 days. Individual spleens were frozen in experiment-sized aliquots. This procedure was repeated to create mBC-CML on each gene-deficient background.

Cell purifications

CD8 cells were purified from lymph nodes (LN) via negative selection as previously described (26) and were >90% pure with CD4+ T cell contamination of less than 0.2% (not shown). CD4 cells were similarly purified by negative selection except anti-CD4 (GK1.5) was omitted and biotin-conjugated anti-CD8 (TIB105; lab-prepared) was added to the antibody depletion cocktail. BM T cells were depleted with anti-Thy1.2 magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn Hills, CA) or anti-Thy1.2 biotin and streptavidin microbeads and the AutoMACS (Miltenyi) (26). BM in all experiments was T cell-depleted and is referred to as “BM” in the text.

Bone marrow transplant and follow up

All transplants were performed according to protocols approved by the Yale University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. B6 mice received 900cGy and were reconstituted with 5×106 T cell-depleted C3H.SW BM, mBC-CML cells, mCP-CML cells or both and GVL-inducing C3H.SW CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. Unless indicated to be otherwise, 1×104 and 1.5×104 mBC-CML cells were infused for CD4− and CD8-mediated GVL experiments, respectively. 7.5×105 BM cells that underwent spin infection with p210-expressing retrovirus were infused in mCP-CML GVL experiments, except as noted. BALB/c mice received 800cGy and were reconstituted with 107 T cell-depleted B6 BM, BALB/c mBC-CML, with or without purified B6 wt or perforin−/− CD8+ T cells. For the B6bm12→B6 strain pairing, B6 mice received 900cGy, 107 B6bm12 BM, mBC-CML, with or without B6bm12 wt or perforin−/− CD4 cells. In experiments with β2M−/− mBC-CML or β2M−/− donor BM, all recipients were treated with 250ug anti-NK1.1 (PK-136; lab prepared) on days −2, −1 and day +7 to prevent NK cell-mediated rejection of MHCI-deficient mBC-CML cells. Mice were bled weekly to quantitate leukemic cells by flow cytometry beginning on around day +9. Mice were scored as having died from leukemia if they had a dominant population of leukemia cells in peripheral blood prior to death and had splenomegaly at necropsy. All deaths in mBC-CML experiments were due to leukemia. A small minority of mice in the mCP-CML experiments died from GVHD and these events are censored with a tick on the survival plots at each occurrence.

Antibodies and flow cytometry

The following antibodies were lab-prepared: anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD8 (TIB105), and anti-NGFR (HB8737). The following antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA): anti-CD3 (17A2), anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti-GR-1 (RB6-8C5), anti-TER-119 (TER-119), anti-H-2Kb (AF6-88.5), anti I-A/I-E, (M5/114.15.2), anti-Fas (Jo2), anti-PD-L1 (MIH5), anti-PD-L2 (TY25), anti-CD19 (ID3), anti-CD117 (2B8), and anti-sca-1 (D7). mCP-CML leukemia stem cells were identified as not staining with a lineage cocktail of antibodies (CD3, CD11b, CD19, GR-1, and TER-119), and expressing c-kit, sca-1 and NGFR. mBC-CML stem cells were EGFP+NGFR+ and lineage−.

Statistical methods

P-values for survival curves were calculated by the log rank test. P-values for comparisons of the numbers of leukemia cells were calculated by Mann-Whitney.

Results

Generation of mBC-CML

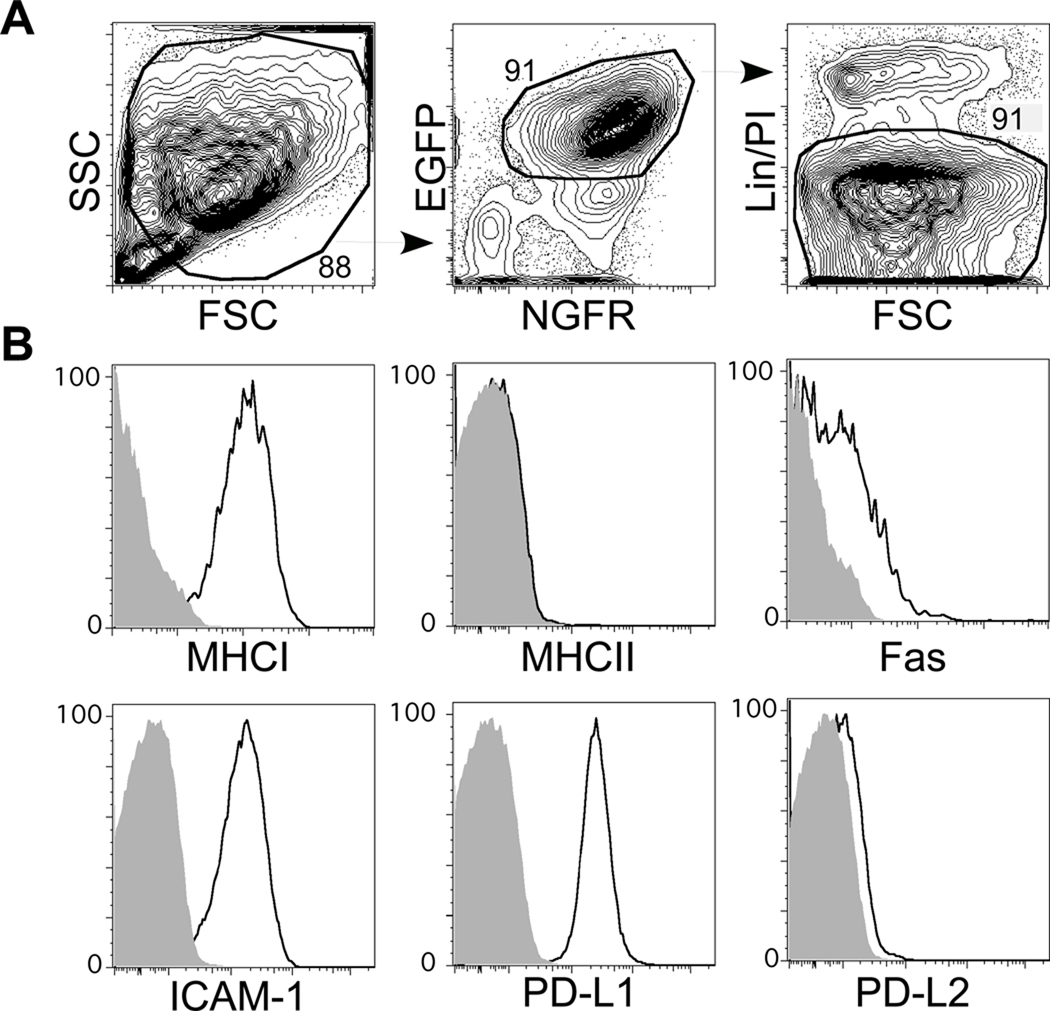

mBC-CML cells were generated as described in Materials and Methods and in Supplemental Figure 1. The majority of mBC-CML cells were lin−EGFP+NGFR+ (Figure 1A) and were clonal as measured by Southern blot analysis of retrovirus integration sites (not shown). The same protocol was used to establish mBC-CML lines using BM from mice deficient in β2M, IAbβ, TRAILR, TNFR/R2, Fas (Faslpr), TRAILR/Fas, PD-L1, PD-L1/L2, and ICAM-1 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Phenotype of mBC-CML cells.

To assess expression of key molecules on wt mBC-CML cells, wt or gene-deficient mBC-CML cells were injected into sublethally irradiated B6 recipients. Shown are representative flow cytometry data from premorbid recipients, analyzed in the same experiment using identical flow cytometry settings. The majority of cells had a high FSC/SSC profile (A) and did not stain with antibodies against lineage-specific markers Gr-1, CD11b, TERR-119, CD19, and CD3). (B) Staining for MHCI, IAb, Fas, ICAM-1, PD-L1 and PD-L2. Open histograms are wild type mBC-CML cells; shaded histograms are from mBC-CML cells genetically deficient in the surface protein being assessed. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments with at least 3 mice from each group analyzed.

mBC-CML is relatively GVL-resistant

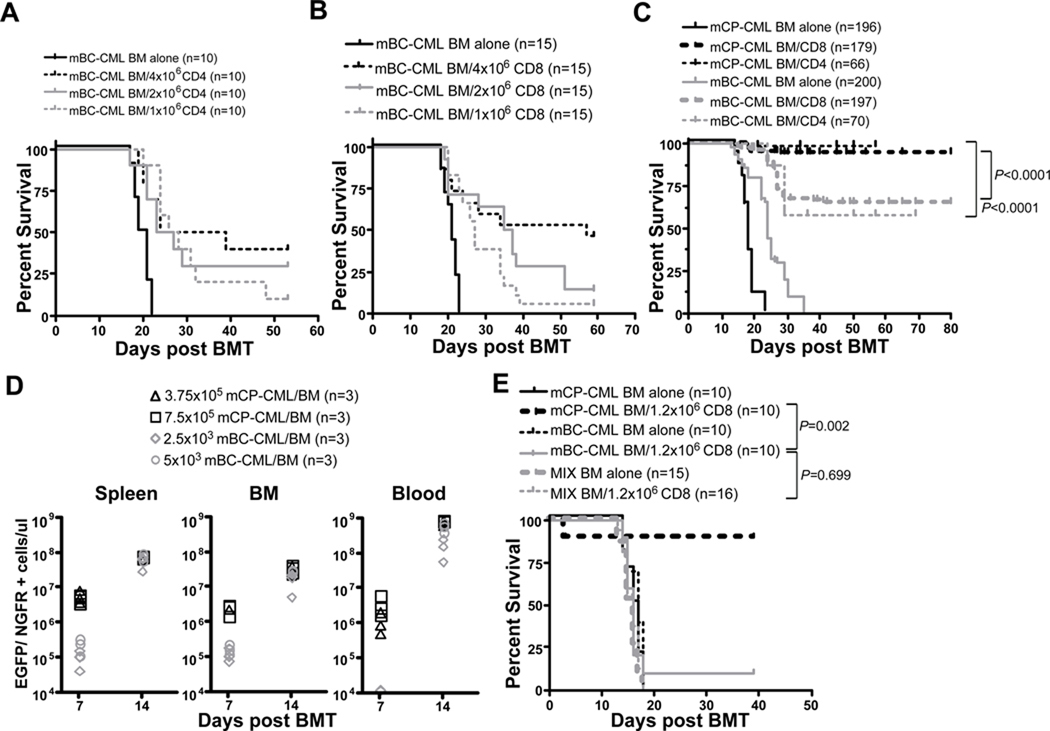

To test the GVL-sensitivity of mBC-CML we utilized the C3H.SW (H-2b)→B6 (H-2b) MHC-matched, minor histocompatibility antigen (miHA)-mismatched strain pairing. This is the same strain pairing we have employed in GVL experiments against mCP-CML (13, 26), allowing a direct comparison of GVL mechanisms against both leukemias. B6 mice were irradiated and reconstituted with C3H.SW BM, 104 (CD4 experiments) or 1.5×104 (CD8 experiments) mBC-CML cells with no T cells or graded doses of purified C3H.SW CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. Mice that did not receive GVL-inducing T cells died from mBC-CML between days 18–23 (Figure 2A, B). CD8 and CD4 doses beyond 106 prolonged survival, but the majority of mice that received T cell doses below 4×106 succumbed to mBC-CML as determined by the presence of EGFP+NGFR+ cells in the PB of mice prior to death and by spleen weight at necropsy (not shown). Even with 4×106 T cells, between 30–50% of mice died from mBC-CML.

Figure 2. mBC-CML is GVL-resistant as compared to mCP-CML.

All data were in the C3H.SW→B6 strain pairing. B6 mice were irradiated and reconstituted with 10,000 (A) or 15,000 (B) mBC-CML cells, C3H.SW BM and graded numbers of C3H.SW CD4 (A) or CD8 cells (B). Shown is percent survival; all deaths were from mBC-CML. P≤0.002 comparing recipients of ≥106 CD4 or CD8 cells to recipients of only mBC-CML and donor BM. (C) Survival data pooled from multiple GVL experiments against mCP-CML and mBC-CML in the C3H.SW→B6 strain pairing. GVL against mCP-CML cells was induced by 1.2×106 CD8 cells or 4×106 CD4 cells. GVL against mBC-CML was induced by 4×106 C3H.SW CD4 or CD8 cells. (D) Kinetics of mCP-CML and mBC-CML development. B6 mice were irradiated and reconstituted with T cell-depleted C3H.SW BM and 2500 or 5000 mBC-CML cells or 3.75×105 or 7.5×105 mCP-CML cells. Mice were sacrificed on days +7 and +14 and leukemia cells were enumerated in blood, spleen and BM. At day +7, mCP-CML cells were more numerous than mBC-CML cells in spleen and BM (P=0.0002) but not blood. At day +14, mBC-CML and mCP-CML cells were present in similar numbers in BM and spleen (P≥0.24) but mCP-CML cells were more numerous than mBC-CML cells in blood (P=0.0043). Data are representative of at least 2 independent experiments. (E) To determine if the presence of mCP-CML cells augments GVL against mBC-CML, B6 mice were irradiated and reconstituted with C3H.SW BM, mBC-CML, mCP-CML or a mix of both, with or without 1.2×106 CD8+ T cells. Data from 1 of 3 experiments with similar results. The data in C were from wild type control transplant groups shown in other figures in this paper, from unpublished experiments, and from GVL experiments in the mCP-CML model previously published in (13, 15, 26).

This contrasts with GVL against mCP-CML. In an analysis of mice transplanted with mBC-CML or mCP-CML in the C3H.SW→B6 strain pairing using standard experimental conditions, 169/179 (94%) of evaluable recipients of mCP-CML and 1.2×106 donor CD8 cells were leukemia-free survivors whereas only 129/197 (65%) recipients of mBC-CML and 4×106 donor CD8 cells survived (Figure 2C). For CD4-mediated GVL both mBC- and mCP-CML mice received 4×106 CD4 cells. Of mCP-CML CD4-recipients, 65/66 mice were leukemia-free as compared to 40/70 mBC-CML recipients (Figure 2C). Survival in mice that received mBC-CML cells, donor BM and no T cells was significantly longer than in the comparable mCP-CML groups (P<0.0001), with high WBC counts and extensive BM and spleen involvement occurring in both. Thus, if anything there was a longer window for alloreactive T cell generation in mBC-CML experiments.

It was possible that mBC-CML was GVL-resistant because of a greater leukemia burden. To test this hypothesis we performed a time-course analysis of mCP-CML and mBC-CML development in mice transplanted with two doses of M-p210-NGFR spin-infected B6 BM or with mBC-CML cells (Figure 2D). We sacrificed mice on days +7 and +14 and enumerated mCP-CML and mBC-CML cells. At day +7, mCP-CML cells were more numerous than mBC-CML cells in spleen and BM but not blood. At day +14, mBC-CML and mCP-CML cells were present in similar numbers in BM and spleen, but mCP-CML cells were more numerous than mBC-CML cells in blood. Importantly, mice that were not sacrificed for analysis died with kinetics similar to that in the majority of our experiments (Supplemental Figure 2).

GVL against mBC-CML is directed against miHAs

mBC-CML cells express human NGFR, p210, NUP98/HOXA9 and EGFP which could be immunogenic (27). To assess the contribution of these leukemia-specific antigens to GVL against mBC-CML, we performed syngeneic B6→B6 transplants with or without B6 LN cells containing 4.6×106 and 4×106 CD4 and CD8 cells, respectively, or 4×106 purified CD8 cells. The addition of syngeneic T cells had no impact on survival as all T cell recipients died with the same kinetics as did mice that received no T cells (Supplemental Figure 3). Thus, NGFR, p210, NUP98/HOXA9 and EGFP were insufficient as target antigens and GVL required an alloresponse against miHAs, which parallels our data on GVL against mCP-CML (13).

mCP-CML does not promote GVL against mBC-CML

In sum these data suggest that mBC-CML is intrinsically GVL-resistant. However, an alternative explanation would be that mCP-CML cells promote alloreactivity as they are capable of differentiating into CD11c+MHCIIbright cells (data not shown), and could have antigen presenting cell (APC) function. To address this possibility we determined whether the presence of mCP-CML increases GVL against mBC-CML. To do so we reconstituted irradiated B6 mice with C3H.SW BM and either B6 mCP-CML, mBC-CML, or a mix of both leukemias. Some mice in each group also received 1.2×106 C3H.SW CD8 cells. As expected, survival was greater in recipients of CD8 cells and only mCP-CML as compared to recipients of CD8 cells and only mBC-CML (Figure 2E). Importantly, recipients of a mix of mCP-CML and mBC-CML and CD8 cells died from mBC-CML with the same kinetics as did mice that received mBC-CML cells and no mCP-CML cells. Thus, the presence of mCP-CML did not augment GVL against mBC-CML. Similar data was obtained in a parallel experiment in which GVL was induced by CD4 cells (data not shown).

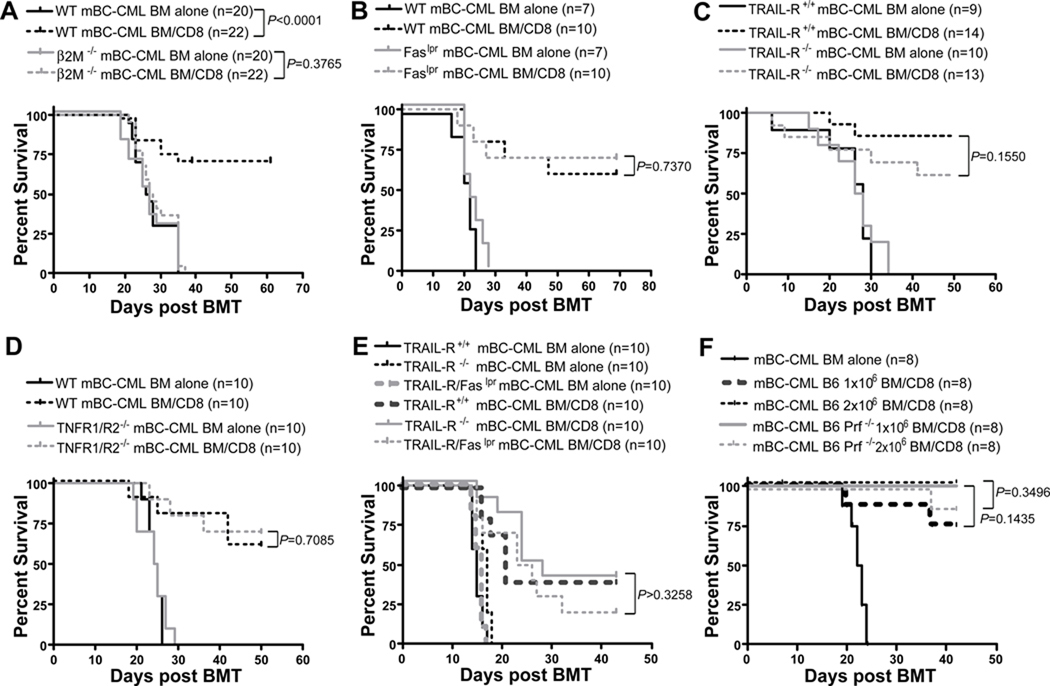

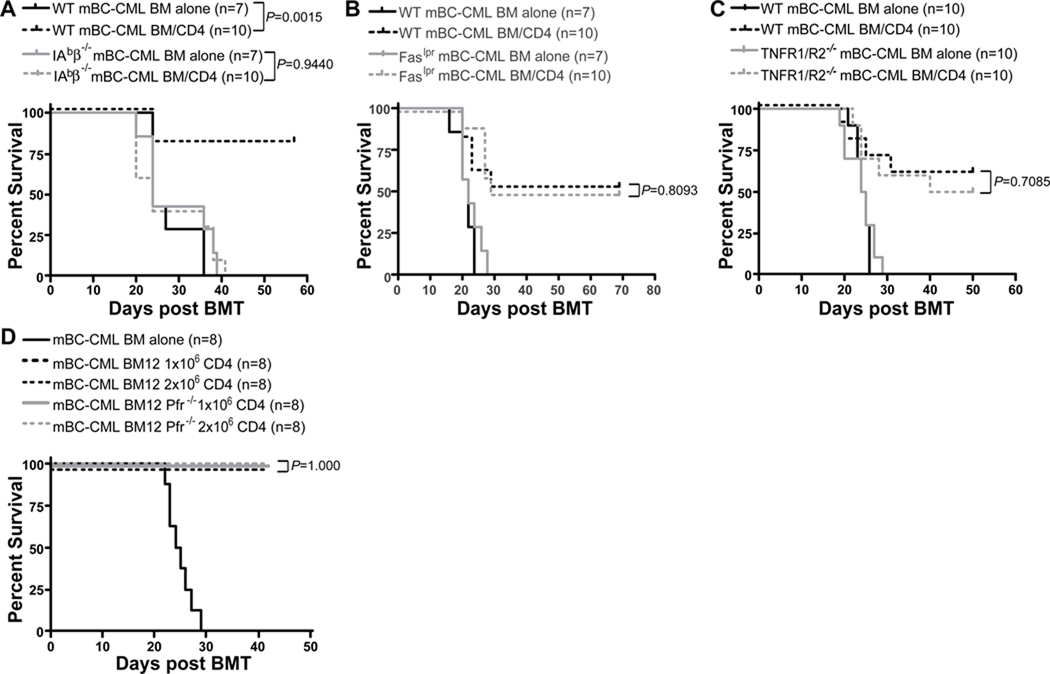

GVL requires cognate interactions between donor T cells and MHC on mBC-CML cells

To determine whether donor T cells must make cognate TCR:MHC interactions with mBC-CML cells we created mBC-CML using BM from β2M−/− (and therefore MHCI-deficient) and IAbβ−/− (and therefore MHCII-deficient) mice and used these leukemias in CD8- and CD4-mediated GVL experiments, respectively. β2M−/− and IAbβ−/− mBC-CML cells were completely resistant to CD8- (Figure 3A) and CD4-mediated (Figure 4A) GVL, respectively. Thus, both CD8 and CD4 cells must make cognate interactions with mBC-CML cells to mediate GVL.

Figure 3. CD8-mediated GVL against mBC-CML requires target MHCI expression but killing mechanisms are redundant.

B6 mice were irradiated and reconstituted with C3H.SW BM, with or without 4×106 C3H.SW CD8 cells with wt mBC-CML or an equivalent number of β2M−/− (A), Faslpr (B), TRAIL-R−/− (C) or TNFR1/R2−/− (D) mBC-CML cells. In E, mice received either TRAILR−/− or TRAIL-R−/−/Faslpr mBC-CML cells. In A, all mice were treated with anti-NK1.1 as in Materials and Methods. To determine whether perforin was required, BALB/c mice were irradiated and reconstituted with B6 BM, 5000 BALB/c mBC-CML cells and 106 CD8 cells from wt or B6 perforin−/− donors (F). For A–E, data are from 1 of 2 experiments with similar results. Data in F are from one experiment.

Figure 4. CD4-mediated GVL requires cognate interactions with MHCII on mBC-CML cells but mechanisms of killing are redundant.

B6 mice were irradiated and reconstituted with C3H.SW BM, with or without 4×106 CD4 cells, with wt mBC-CML or an equivalent number of IAbβ−/− (A), Faslpr (B) or TNFR1/R2−/− (C) mBC-CML. To test the role of perforin-mediated killing, B6 mice were irradiated and reconstituted with wt B6 mBC-CML, B6bm12 BM, with no CD4 cells or 1×106 or 2×106 CD4 cells from B6bm12 perforin−/− or wt B6 mice. Data from 1 of 2 experiments with similar results for TNFR1/R2−/− and Faslpr mBC-CML. Data from 1 experiment for IAbβ−/− mBC-CML and perforin−/− CD4 cells.

Killing mechanisms against mBC-CML are redundant

Having established that direct cytotoxicity is required for both CD4- and CD8-mediated GVL, we investigated mechanisms of T cell killing by creating mBC-CML deficient in Fas (Faslpr), TRAIL-R, TNFR1/R2 and TRAIL-R and Fas (TRAIL-R/Faslpr). CD8- (Figure 3) and CD4-mediated GVL (Figure 4) were equivalent against Faslpr, TRAILR−/− (CD8-mediated GVL only) and TNFR1/R2−/− mBC-CML. CD8-mediated GVL was also unimpaired against TRAILR−/−/Faslpr mBC-CML (Figure 3E). Importantly, in all experiments recipients of wt or gene-deficient mBC-CML without donor T cells died with similar kinetics (P≥0.288), indicating that the absence of these death receptors did not have a major effect on leukemia pathogenicity.

Because no gene deletion renders cells specifically resistant to perforin/granzyme-mediated killing, we used donor perforin−/− T cells to examine the importance of this pathway. For these experiments we employed the B6→BALB/c (CD8-mediated GVL) and B6bm12→B6 (CD4-mediated GVL) strain pairings as perforin−/− C3H.SW mice were not available. BALB/c mice were irradiated and reconstituted with B6 BM and BALB/c mBC-CML with no CD8 cells or with purified B6 wt or perforin−/− CD8+ T cells (Figure 3F). For CD4-mediated GVL, B6 mice were irradiated and reconstituted with B6bm12 BM with no T cells or with B6bm12 wt or perforin−/− (14) spleen cells containing 1×106 or 2×106 CD4+ T cells (Figure 4D). In both models, GVL induced by wt or perforin−/− T cells was equivalent.

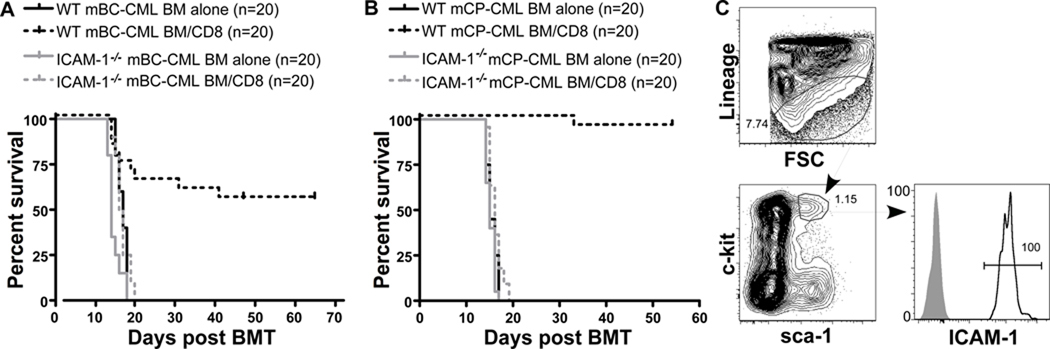

ICAM-1 on mBC-CML and mCP-CML cells is required for CD8-mediated GVL

ICAM-1 interactions with LFA-1 on T cells promote adhesion and formation of a stable immunologic synapse (28). ICAM-1 is also highly and uniformly expressed on mBC-CML cells (Figure 1). We therefore created ICAM-1−/− mBC-CML and mCP-CML and tested them in CD8-mediated GVL experiments in the C3H.SW→B6 strain pairing (Figure 5). ICAM-1−/− mBC-CML was nearly completely resistant to GVL as all CD8-recipients died from mBC-CML by day +20. ICAM-1−/− mCP-CML was also GVL-resistant and concordant with this, ICAM-1 was highly expressed on lineage−sca-1+c-kit+ mCP-CML stem cells (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. ICAM-1 on mCP-CML and mBC-CML cells is required for GVL.

(A) B6 mice were irradiated and reconstituted with C3H.SW BM, 5000 wt or ICAM-1−/− mBC-CML cells, with or without 4×106 C3H.SW CD8+ T cells. Data combined from 2 experiments with similar results. P<0.0001 comparing either CD8-recipient group with its BM alone control. (B) B6 mice were irradiated and reconstituted with C3H.SW BM, wt or ICAM-1−/− mCP-CML, with or without 1.2×106 C3H.SW CD8 cells. Data combined from 2 experiments with similar results. P<0.0001 comparing either CD8-recipient group with its BM alone control. (C) Expression of ICAM-1 on mCP-CML stem cells. Stem cells were lineage (Gr-1, CD11b, TERR-119, CD19, and CD3) and sca-1+c-kit+NGFR+. Open histogram, ICAM-1; shaded histogram, isotype control. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

Host APCs are required for both CD4- and CD8-mediated GVL

To determine whether host APCs are required for GVL against mBC-CML we used β2M−/− or IAbβ−/− recipients in CD8 and CD4 GVL experiments, respectively. Based on our previous data that host APCs are essential for CD8-mediated GVHD in the C3H.SW→B6 strain pairing (29), we anticipated that host APCs would be required for CD8-mediated GVL. However, contrary to that expectation, we observed similar CD8-mediated GVL in wt B6 and B6 β2M−/− hosts and CD4-mediated GVL in wt B6 and IAbβ−/− hosts (not shown). We were surprised by these results, and considered the possibility that GVL was initiated by APCs contaminating the mBC-CML cells, as we used splenocytes from wt mice with mBC-CML as the source of leukemia cells. We therefore repeated these GVL experiments with sort-purified mBC-CML cells. With sort-purified mBC-CML cells, we observed no GVL in either β2M−/− (Figure 6A) or IAbβ−/− (Figure 6B) hosts whereas GVL in wt B6 recipients was as in prior experiments. Thus a small number of contaminating B6 splenic APCs was sufficient to induce GVL.

Figure 6. CD8- and CD4-mediated GVL require intact host APCs but donor APCs are not required for CD8-mediated GVL. Shown are survival curves. All deaths were from mBC-CML.

In A and C, B6 or B6 β2M−/− hosts were irradiated and reconstituted with C3H.SW BM, B6 mBC-CML (sort purified in A; sort-purified and unsorted in C), with or without 4×106 C3H.SW CD8+ T cells. In B, B6 or IAbβ−/− hosts were irradiated and reconstituted with C3H.SW BM, sort-purified mBC-CML cells and 4×106 C3H.SW CD4+ T cells. (D) B6 mice were irradiated and reconstituted with either wt or β2M−/− C3H.SW BM, B6 mBC-CML cells, with or without 4×106 C3H.SW CD8+ T cells. All mice in D were treated with anti-NK1.1 on days −2, −1 and +7. Data in A, B and D are representative of at least 2 experiments with similar results. Data in C wherein sorted and unsorted mBC-CML cells were used in a single experiment are from 1 experiment. Data with unsorted mBC-CML cells were confirmed in 3 experiments with similar results.

To confirm this result we compared GVL in β2M−/− hosts against unsorted mBC-CML cells (containing 15,000 live EGFP+ cells) and 15,000 EGFP+ cells sorted from them, in a single experiment. We observed no GVL in β2M−/− recipients of sorted mBC-CML cells whereas GVL was intact in recipients of unsorted mBC-CML cells (Figure 6C). GVL against sorted and unsorted mBC-CML cells was similar in control wt B6 hosts transplanted in the same experiment (not shown). The presort frequency of EGFP+ cells was 65%, so at most 5250 nonleukemic splenocytes were sufficient to initiate GVL.

Donor-derived APCs are not required for CD8-mediated GVL

To determine whether donor-derived APCs are required for CD8-mediated GVL we used C3H.SW β2M−/− mice as BM donors. B6 mice were irradiated and reconstituted with wt or β2M−/− C3H.SW BM, B6 mBC-CML cells, with or without donor CD8+ T cells. All mice (including recipients of wt donor BM) were treated with anti-NK1.1 on days −2, −1 and +7 to prevent NK cell-mediated rejection of β2M−/− donor BM. GVL was equivalent in recipients of wt and β2M−/− BM (Figure 6D). Thus, donor-derived T cells exclusively primed on host APCs were sufficient to mediate GVL.

PDL1/2 on mCP-CML cells but not mBC-CML cells inhibits GVL

The B7-family members PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-L2 (B7-DC) deliver inhibitory signals to activated PD-1+ T cells and have been implicated in resistance to cancer immunotherapy (30, 31). PD-L1 is expressed both by mCP-CML and mBC-CML cells, including their stem cells (Figure 1 and Supplemental Figure 4). We therefore created PD-L1-deficient mCP-CML and mBC-CML and tested their immunogenicity in CD8-mediated GVL experiments in the C3H.SW→B6 strain pairing. Despite clear PD-L1 expression on wt leukemias, neither PD-L1-deficient mCP-CML nor mBC-CML was more sensitive to GVL, even when GVL was induced by lower numbers of CD8 cells that resulted in reduced survival (Figure 7A, B).

Figure 7. PD-L1 and PD-L2 on mCP-CML but not mBC-CML cells inhibit GVL.

A–E are survival curves. P values noted on the figures compare recipients of wt and gene-deficient leukemias given the same T cell dose. B6 mice were irradiated and reconstituted with C3H.SW BM, wt or PD-L1−/− (A) or PD-L1/L2−/− (C) mBC-CML with or without C3H.SW CD8+ T cells. For A, P=0.09 and P=0.0023 comparing recipients of wt or PD-L1−/− mBC-CML and 2×106 or 4×106 CD8 cells, respectively, with their BM alone controls. For C, P≤0.0046 comparing recipients of wt or PD-L1/L2 mBC-CML and 4×106 CD8 cells with their BM alone controls. P=0.0059 and P=0.94 comparing recipients of 2×106 CD8 cells and wt or PD-L1/L2−/− mBC-CML (respectively) and their BM alone controls. (B, D and E) B6 mice were irradiated and reconstituted with C3H.SW BM, 7.5×105 wt, PD-L1/L2−/− or a mix of PD-L1/L2 and wt mCP-CML cells (3.75×105 of each), with no T cells or with 1.2×106 or 3×105 C3H.SW CD8 cells. For B, P≤0.0007 comparing any T cell recipient group to its BM alone control. For D, P<0.0001 comparing any T cell recipient group to its BM alone control. For E, P<0.0001 comparing recipients of 3×105 CD8 cells and PD-L1/L2 mCP-CML vs a mix of wt and PD-L1/L2−/− mCP-CML cells. P≤0.0033 comparing recipients of CD8 cells and wt or PD-L1/L2−/− mCP-CML with their BM alone controls. P=0.069 comparing recipients of wt plus PD-L1/L2−/− mCP-CML with or without CD8 cells. (F) Mice from the experiment depicted in (E) were bled at the indicated days and EGFP+ wt and NGFR+ PD-L1/L2−/− mCP-CML cells were enumerated. Note the reduction in PD-L1/L2−/− mCP-CML cells vs. wt mCP-CML cells in CD8 recipients of either PD-L1/L2 mCP-CML or a mix of wt and PD-L1/L2−/− mCP-CML (“MIX”). P≤0.01 comparing numbers of leukemia cells in recipients of CD8 cells and wt vs PD-L1/L2−/− mCP-CML on days 18 and 21. P=0.016 comparing numbers of wt and PD-L1/L2−/− mCP-CML cells in “MIX” CD8 recipients on days 18 and 21. Data in A and B are from one experiment each; data in C, E and F are representative of 2 experiments each with similar results. Data in D are representative of 3 experiments with similar results.

We next considered that because mCP-CML and mBC-CML are hematopoietic in origin, they could also express PD-L2. We therefore created PD-L1/PD-L2−/− mCP-CML and mBC-CML cells and used these in GVL experiments in the C3H.SW→B6 strain pairing. We again included groups that received lower doses of donor CD8 cells to increase our ability to detect differences in GVL sensitivity. The absence of PD-L1/L2 did not render mBC-CML cells more GVL-sensitive (Figure 7C). In contrast, PD-L1/PD-L2−/− mCP-CML was far more GVL-sensitive than wt mCP-CML (Figure 7D). Therefore, either PD-L1 or PD-L2 on mCP-CML cells can inhibit GVL and both must be ablated for GVL to be enhanced.

As mCP-CML cells can differentiate into APCs and not all cells that undergo spin infection are bcr-abl-transduced, it was possible that the absence of PD-L1/PD-L2 on infused cells augmented alloreactive T cell priming, rather than failing to inhibit PD-1+ T cells in the effector phase. To distinguish these possibilities, we performed GVL experiments wherein hosts received wt, PD-L1/PD-L2−/− or a mix of wt and PD-L1/PD-L2−/− mCP-CML cells, with or without 3×105 GVL-inducing CD8+ T cells. We reasoned that if the absence of PD-L1/PD-L2 primarily augments T cell priming, GVL against wt mCP-CML should be potentiated by PD-L1/PD-L2−/− mCP-CML cells. Whereas if the action of PD-L1/PD-L2 is in the effector phase, PD-L1/PD-L2−/− mCP-CML cells would not increase GVL against wt mCP-CML. To distinguish the two leukemias, we used M-p210/NGFR and M-p210/EGFP to infect PD-L1/PD-L2−/− and wt BM, respectively. As expected, PD-L1/PD-L2 mCP-CML was more sensitive to GVL (Figure 7E). However, survival in recipients of a mix of wt and PD-L1/PD-L2−/− mCP-CML cells and CD8 cells was identical to recipients of only wt mCP-CML cells and CD8 cells and worse than that in recipients of PD-L1/PD-L2−/− mCP-CML and CD8 cells. Mice were serially bled to enumerate NGFR+ and EGFP+ cells (Figure 7F). At days +7-+13, there were more NGFR+ PD-L1/PD-L2−/− than EGFP+ wt mCP-CML cells in recipients of a mix of the two leukemias, whether or not they received CD8 cells. However, on days +18 and +21, there were significantly more EGFP+ wt cells in CD8−recipients, demonstrating more efficient clearance of PD-L1/PD-L2−/− mCP-CML cells.

Discussion

In clinical transplantation, leukemia relapse remains the greatest single cause of mortality (32). The risk of relapse is not uniform across different hematopoietic malignancies. Rather, certain leukemias are as a group GVL-sensitive whereas others are relatively resistant. Improved clinical outcomes will depend on a mechanistic understanding of both GVL sensitivity and resistance. A major obstacle in achieving this has been the absence of clinically-relevant and genetically manipulable GVL-sensitive and GVL-resistant mouse leukemias. This was the motivation in adapting mCP-CML and mBC-CML models for GVL experiments.

The central findings of our prior work on GVL against mCP-CML were that cognate interactions between leukemia cells and CD4+ or CD8+ T cells are required and that GVL-inducing T cells used redundant killing mechanisms (13–15). We speculated that this redundancy at least in part accounted for GVL sensitivity and predicted that more GVL-resistant leukemias would be more reliant on single death-inducing pathways(1). In the present work we analyzed GVL against mBC-CML mostly utilizing the same strain pairing (C3H.SW→B6) employed in our mCP-CML studies, which allows for a direct comparison of GVL against both leukemias.

As we aim to understand GVL-resistance by comparing GVL against mCP-CML with GVL against mBC-CML, it was important that we establish that mBC-CML is relatively GVL-resistant and we did so in several complementary ways. GVL against mBC-CML required much higher doses of donor CD8 cells. Even with these higher doses, survival, assessed in a large cohort of similarly transplanted mice from multiple independent experiments, was less in mBC-CML recipients than in mCP-CML recipients of more than 3-fold fewer CD8 cells. mCP-CML was not relatively GVL-sensitive because mCP-CML cells promoted a more effective alloreactive T cell response as the coinfusion of mCP-CML cells did not render mBC-CML more GVL-sensitive. Nor was GVL-resistance due to a larger mBC-CML leukemia burden as mCP-CML cells were at least as numerous in BM, spleen and blood at multiple early time points. In most experiments, without donor T cells, recipients of mBC-CML died later than did recipients of mCP-CML, and therefore if anything, there was more time to develop an alloimmune response.

Cognate interactions between donor T cell antigen receptors and MHC on mBC-CML cells were absolutely required for both CD4- and CD8-mediated GVL. That MHCII− mBC-CML was completely resistant to CD4-mediated GVL is congruent with the same finding for CD4-mediated GVL against mCP-CML (13, 15). These data suggest that direct cytolysis is the general mode by which CD4+ T cells mediate GVL, rather than indirect killing through accessory cells such as macrophages. In contrast, CD4 cells can mediate GVHD indirectly, without making TCR-mediated contact with MHCII+ host nonhematopoietic cells (15, 33) and thus interfering with these indirect mechanisms may decrease GVHD while preserving GVL. Direct target killing by CD4 cells has also been demonstrated in vivo by others (34, 35). However, these experiments were with ex vivo activated TCR transgenic T cells or T cell lines whereas our data were with polyclonal CD4 cells activated exclusively in vivo, which is more clinically relevant.

Indirect killing by CD4 cells has long been advocated as an important mechanism for anti-tumor T cell responses (36–40). However, this conclusion has been based on data with tumor cell lines in which MHCII was undetectable by flow cytometry, whereas we used primary leukemias that were genetically MHCII-deficient. This is especially relevant given that MHCII expression in wt mCP-CML (not shown) and mBC-CML stem cells is indistinguishable from that in IAbβ−/− leukemias (Figure 1), and had IAbβ−/− leukemias not been available, we could have mistakenly concluded that CD4 cells acted indirectly. It is possible that very few MHCII molecules are sufficient (below what we can detect by flow cytometry), that MHCII is induced in vivo by the alloimmune response, or that a small subset of critical cells express MHCII.

Having established that TCR:MHC contact was required, we focused on T cell cytolytic mechanisms. We had anticipated that killing mechanisms would lack the redundancy observed for GVL against mCP-CML. However, impairment of any single effector mechanism, or Fas and TRAIL-R together, had no impact on GVL against mBC-CML. These data argue against resistance to single killing mechanisms as a cause for GVL resistance. Numerous prior GVL studies have suggested reliance on a single killing mechanism (reviewed in (1)). Perforin was most commonly implicated, though FasL and TRAIL had essential roles in some models. These prior studies used leukemia cell lines, commonly induced by mutagenesis and passaged over many years, as targets for alloreactive T cells. These lines may have initially lacked one or more death receptor types or lost their expression with extended passaging, leading to reliance on a smaller subset of potential killing mechanisms. Previous work on killing mechanisms have also mostly utilized gene-deficient T cells and reagent-based blockade of death receptor ligands, which could alter effector T cell generation (41, 42), thereby clouding the importance of these pathways to end effector killing. In contrast, in our experiments (except for those with perforin−/− T cells) only end effector killing was blocked. Another advantage of our gene-deficient leukemias is that the targeted death receptors were unequivocally absent; whereas leukemia cell lines may still express a given death receptor at a low level or be induced to express it in vivo, even if this is not apparent by flow cytometry or by RT-PCR.

Our data for the first time definitively identify ICAM-1 on leukemia cells as an absolute requirement for CD8-mediated GVL. Because ICAM-1:LFA-1 interactions both promote T cell activation by APCs and T cell target killing (43), reduced GVL with reagent-based ICAM-1 or LFA-1 blockade could be due to reduced T cell activation rather than target killing. The use of ICAM-1−/− leukemias allowed us to isolate the role for ICAM-1 in the effector phase.

Because others and we have proposed inhibiting APCs as a strategy for decreasing GVHD, it was important to evaluate APC requirements for GVL against mBC-CML. Recipient APCs were required for both CD8- and CD4-mediated GVL against mBC-CML, and this confirms results from Reddy et al (44) for GVL against a different model leukemia. That host APCs were required for optimal CD8-mediated GVL was anticipated given their essential role in CD8-mediated GVHD in this strain pairing (29). The reliance on host APCs also supports the idea that leukemias themselves are not an important source of miHAs for alloreactive T cell priming. However, it was surprising that CD4-mediated GVL also required intact recipient APCs. Exogenously acquired antigens are more efficiently presented on MHCII than on MHCI. Consistent with this, recipient APCs are not required for CD4-mediated GVHD across only miHAs (45, 46). The divergence in the roles of host APCs in CD4-mediated GVL and GVHD could be due to how the kinetics of donor T cell activation affects outcomes. Recipient APCs are available immediately to prime donor CD4 cells, whereas donor-derived APCs must differentiate from BM precursors and traffic to secondary lymphoid tissues. Therefore without functional host APCs, alloreactive T cell generation is likely delayed, which would compromise the early GVL response. No more than 5250 infused nonleukemic spleen cells restored GVL in MHC-deficient hosts. Only a fraction of these would be functional APCs and even fewer would make it to secondary lymphoid tissues. This highlights how conducive the early post-transplant period is to alloreactive T cell priming.

Another potential mechanism for GVL-resistance we considered was the interaction between PD-L1/PD-L2 on leukemic cells with PD-1 on T cells. PD-L1 expression by cancer cell lines can suppress anti-tumor T cell immunity via engagement of PD-1 on T cells (31). mCP-CML, mBC-CML and their stem cells brightly expressed PD-L1. Yet, the absence of PD-L1/PD-L2 only promoted GVL against mCP-CML. By analyzing GVL responses in recipients of a mix of wt and PD-L1/L2−/− mCP-CML we could demonstrate that PD-L1/L2 acts in the effector phase. Because GVL was not augmented when mCP-CML was only PD-L1−/−, we can conclude that PD-L1 and PD-L2 are redundant. There has been little prior evidence supporting a role for PD-L2 in inhibiting anti-tumor effects, likely due its relatively limited expression, mostly on DCs, macrophages and B1 cells (31). In one study its overexpression on a cell line augmented tumor rejection in a PD-1-independent fashion (47). Of note, PD-L2 expression was minimal on mCP-CML leukemia stem cells (Supplemental Figure 4). Either this low level expression is sufficient, or it is upregulated in vivo by alloimmune-induced inflammation (48, 49).

These data highlight that the mere expression of PD-L1 or PD-L2 on a cancer cell does not assure that PD-ligand blockade will enhance T cell killing. We do not know why the absence of PD-L1/PD-L2 on mBC-CML did not augment GVL. Alloreactive CD8 cells in these experiments should have been suppressible by PD-ligands given that PD-L1/L2 on mCP-CML cells inhibited alloreactive CD8 cells in the same C3H.SW→B6 strain pairing. This suggests that the absence of this suppression was insufficient to overcome the intrinsic GVL-resistance of mBC-CML cells. PD-L1/PD-L2 may also act in-part through outside-in signaling (30) and these pathways may differ in the two leukemias. This remains to be further explored.

The role of PD-1 in immunity against mBC-CML has also been studied by Mumprecht et al (50), though in a syngeneic rejection model. They found that survival in sublethally irradiated B6 PD-1−/− recipients of p210/NUP98-HOXA9-transduced wt B6 BM was improved as compared to that in control sublethally irradiated wt B6 mice, which contrasts with our results with PD-L1 and PD-L1/L2-deficient mBC-CML. Our studies differ substantially from these. mBC-CML cells in our hands and others (16, 21) were mostly lineage− whereas the majority of mBC-CML cells in Mumprecht et al expressed CD11b and Gr-1. Their experimental design, which used PD-1-deficient T cells rather than PD-ligand-deficient mBC-CML, could also have promoted more efficient T cell priming whereas in our experiments only the effector phase was affected.

In sum, our studies indicate that GVL against both mCP-CML and mBC-CML is directed at miHAs and that at least the early GVL response requires competent host APCs. This reliance on host APCs and the failure of mCP-CML to rescue GVL against mBC-CML suggests that similar miHA-reactive T cells are generated regardless of the type of leukemia, which supports the hypothesis that GVL-resistance is cell-intrinsic to mBC-CML cells. Despite this cell-intrinsic resistance to T cell killing, we found that GVL against both leukemias share the same pathways of recognition and killing and individually only MHC and ICAM-1 expression were essential. Our experiments looked at the extreme example—complete absence of MHC or ICAM-1. Nonetheless these results indicate that decreased expression of either MHC or ICAM-1 would reduce the avidity of alloreactive T cells for their targets thereby diminishing GVL. That T cells employ redundant killing mechanisms against both mCP-CML and mBC-CML, but mBC-CML is nonetheless GVL-resistant, supports the hypothesis that even with equivalent T cell recognition, a class of leukemias could be resistant due to differences downstream from death receptor ligation or the introduction of granzymes. If identified, these resistance pathways would be targets for rendering GVL-resistant cancers more susceptible to T cell killing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Yale Animal Resources Center for expert animal care.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH CA 096943 and CM020049. W.D.S is a recipient of a Clinical Scholar award from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

References

- 1.van den Brink MR, Burakoff SJ. Cytolytic pathways in haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:273–281. doi: 10.1038/nri775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleakley M, Riddell SR. Molecules and mechanisms of the graft-versus-leukaemia effect. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:371–380. doi: 10.1038/nrc1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horowitz MM, Gale RP, Sondel PM, Goldman JM, Kersey J, Kolb HJ, Rimm AA, Ringden O, Rozman C, Speck B, et al. Graft-versus-leukemia reactions after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1990;75:555–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolb HJ. Graft-versus-leukemia effects of transplantation and donor lymphocytes. Blood. 2008;112:4371–4383. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-077974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Childs R, Chernoff A, Contentin N, Bahceci E, Schrump D, Leitman S, Read EJ, Tisdale J, Dunbar C, Linehan WM, Young NS, Barrett AJ. Regression of metastatic renal-cell carcinoma after nonmyeloablative allogeneic peripheral-blood stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:750–758. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009143431101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gahrton G, Svensson H, Cavo M, Apperly J, Bacigalupo A, Bjorkstrand B, Blade J, Cornelissen J, de Laurenzi A, Facon T, Ljungman P, Michallet M, Niederwieser D, Powles R, Reiffers J, Russell NH, Samson D, Schaefer UW, Schattenberg A, Tura S, Verdonck LF, Vernant JP, Willemze R, Volin L The European Group for, and T. Marrow. Progress in allogenic bone marrow and peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma: a comparison between transplants performed 1983--93 and 1994--8 at European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation centres. British Journal of Haematology. 2001;113:209–216. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGlave P. Bone marrow transplants in chronic myelogenous leukemia: an overview of determinants of survival. Semin Hematol. 1990;27:23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porter DL, Collins RH, Jr., Hardy C, Kernan NA, Drobyski WR, Giralt S, Flowers ME, Casper J, Leahey A, Parker P, Mick R, Bate-Boyle B, King R, Antin JH. Treatment of relapsed leukemia after unrelated donor marrow transplantation with unrelated donor leukocyte infusions. Blood. 2000;95:1214–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Passweg JR, Tiberghien P, Cahn JY, Vowels MR, Camitta BM, Gale RP, Herzig RH, Hoelzer D, Horowitz MM, Ifrah N, Klein JP, Marks DI, Ramsay NK, Rowlings PA, Weisdorf DJ, Zhang MJ, Barrett AJ. Graft-versus-leukemia effects in T lineage and B lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21:153–158. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SJ, Klein JP, Barrett AJ, Ringden O, Antin JH, Cahn JY, Carabasi MH, Gale RP, Giralt S, Hale GA, Ilhan O, McCarthy PL, Socie G, Verdonck LF, Weisdorf DJ, Horowitz MM. Severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease: association with treatment-related mortality and relapse. Blood. 2002;100:406–414. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.2.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daley GQ, Van Etten RA, Baltimore D. Induction of chronic myelogenous leukemia in mice by the P210bcr/abl gene of the Philadelphia chromosome. Science. 1990;247:824–830. doi: 10.1126/science.2406902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Ilaria RL, Jr., Million RP, Daley GQ, Van Etten RA. The P190, P210, and P230 forms of the BCR/ABL oncogene induce a similar chronic myeloid leukemia-like syndrome in mice but have different lymphoid leukemogenic activity. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1399–1412. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matte CC, Cormier J, Anderson BE, Athanasiadis I, Liu J, Emerson SG, Pear W, Shlomchik WD. Graft-versus-leukemia in a retrovirally induced murine CML model: mechanisms of T-cell killing. Blood. 2004;103:4353–4361. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng H, Matte-Martone C, Li H, Anderson BE, Venketesan S, Tan H Sheng, Jain D, McNiff J, Shlomchik WD. Effector memory CD4+ T cells mediate graft-versus-leukemia without inducing graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2008;111:2476–2484. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-109678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matte-Martone C, Liu J, Jain D, McNiff J, Shlomchik WD. CD8+ but not CD4+ T cells require cognate interactions with target tissues to mediate GVHD across only minor H antigens, whereas both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells require direct leukemic contact to mediate GVL. Blood. 2008;111:3884–3892. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-125294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dash AB, Williams IR, Kutok JL, Tomasson MH, Anastasiadou E, Lindahl K, Li S, Van Etten RA, Borrow J, Housman D, Druker B, Gilliland DG. A murine model of CML blast crisis induced by cooperation between BCR/ABL and NUP98/HOXA9. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7622–7627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102583199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borrow J, Shearman AM, Stanton VP, Jr., Becher R, Collins T, Williams AJ, Dube I, Katz F, Kwong YL, Morris C, Ohyashiki K, Toyama K, Rowley J, Housman DE. The t(7;11)(p15;p15) translocation in acute myeloid leukaemia fuses the genes for nucleoporin NUP98 and class I homeoprotein HOXA9. Nat Genet. 1996;12:159–167. doi: 10.1038/ng0296-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto K, Nakamura Y, Saito K, Furusawa S. Expression of the NUP98/HOXA9 fusion transcript in the blast crisis of Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myelogenous leukaemia with t(7;11)(p15;p15) Br J Haematol. 2000;109:423–426. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahuja HG, Popplewell L, Tcheurekdjian L, Slovak ML. NUP98 gene rearrangements and the clonal evolution of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer. 2001;30:410–415. doi: 10.1002/1098-2264(2001)9999:9999<::aid-gcc1108>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroon E, Thorsteinsdottir U, Mayotte N, Nakamura T, Sauvageau G. NUP98-HOXA9 expression in hemopoietic stem cells induces chronic and acute myeloid leukemias in mice. Embo J. 2001;20:350–361. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neering SJ, Bushnell T, Sozer S, Ashton J, Rossi RM, Wang PY, Bell DR, Heinrich D, Bottaro A, Jordan CT. Leukemia stem cells in a genetically defined murine model of blast-crisis CML. Blood. 2007;110:2578–2585. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-073031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diehl GE, Yue HH, Hsieh K, Kuang AA, Ho M, Morici LA, Lenz LL, Cado D, Riley LW, Winoto A. TRAIL-R as a negative regulator of innate immune cell responses. Immunity. 2004;21:877–889. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin T, Yoshimura K, Crafton EB, Tsuchiya H, Housseau F, Koseki H, Schulick RD, Chen L, Pardoll DM. In vivo costimulatory role of B7-DC in tuning T helper cell 1 and cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1531–1541. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu H, Gonzalo JA, St Pierre Y, Williams IR, Kupper TS, Cotran RS, Springer TA, Gutierrez-Ramos JC. Leukocytosis and resistance to septic shock in intercellular adhesion molecule 1-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1994;180:95–109. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morita S, Kojima T, Kitamura T. Plat-E: an efficient and stable system for transient packaging of retroviruses. Gene Ther. 2000;7:1063–1066. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matte CC, Liu J, Cormier J, Anderson BE, Athanasiadis I, Jain D, McNiff J, Shlomchik WD. Donor APCs are required for maximal GVHD but not for GVL. Nat Med. 2004;10:987–992. doi: 10.1038/nm1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersson G, Illigens BM, Johnson KW, Calderhead D, LeGuern C, Benichou G, White-Scharf ME, Down JD. Nonmyeloablative conditioning is sufficient to allow engraftment of EGFP-expressing bone marrow and subsequent acceptance of EGFP-transgenic skin grafts in mice. Blood. 2003;101:4305–4312. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lebedeva T, Dustin ML, Sykulev Y. ICAM-1 co-stimulates target cells to facilitate antigen presentation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shlomchik WD, Couzens MS, Tang CB, McNiff J, Robert ME, Liu J, Shlomchik MJ, Emerson SG. Prevention of graft versus host disease by inactivation of host antigen- presenting cells. Science. 1999;285:412–415. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5426.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azuma T, Yao S, Zhu G, Flies AS, Flies SJ, Chen L. B7-H1 is a ubiquitous antiapoptotic receptor on cancer cells. Blood. 2008;111:3635–3643. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-123141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zou W, Chen L. Inhibitory B7-family molecules in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:467–477. doi: 10.1038/nri2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bishop MR, Alyea EP, 3rd, Cairo MS, Falkenburg JH, June CH, Kroger N, Little RF, Miller JS, Pavletic SZ, Porter D, Riddell SR, van Besien K, Wayne AS, Weisdorf DJ, Wu R, Giralt S. Introduction to the reports from the National Cancer Institute First International Workshop on the Biology, Prevention, and Treatment of Relapse after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:563–564. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teshima T, Ordemann R, Reddy P, Gagin S, Liu C, Cooke KR, Ferrara JL. Acute graft-versus-host disease does not require alloantigen expression on host epithelium. Nat Med. 2002;8:575–581. doi: 10.1038/nm0602-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quezada SA, Simpson TR, Peggs KS, Merghoub T, Vider J, Fan X, Blasberg R, Yagita H, Muranski P, Antony PA, Restifo NP, Allison JP. Tumor-reactive CD4(+) T cells develop cytotoxic activity and eradicate large established melanoma after transfer into lymphopenic hosts. J Exp Med. 2010;207:637–650. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bogen B, Malissen B, Haas W. Idiotope-specific T cell clones that recognize syngeneic immunoglobulin fragments in the context of class II molecules. Eur J Immunol. 1986;16:1373–1378. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830161110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mumberg D, Monach PA, Wanderling S, Philip M, Toledano AY, Schreiber RD, Schreiber H. CD4(+) T cells eliminate MHC class II-negative cancer cells in vivo by indirect effects of IFN-gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8633–8638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corthay A, Skovseth DK, Lundin KU, Rosjo E, Omholt H, Hofgaard PO, Haraldsen G, Bogen B. Primary antitumor immune response mediated by CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2005;22:371–383. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hung K, Hayashi R, Lafond-Walker A, Lowenstein C, Pardoll D, Levitsky H. The central role of CD4(+) T cells in the antitumor immune response. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2357–2368. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenberg PD, Cheever MA, Fefer A. Eradication of disseminated murine leukemia by chemoimmunotherapy with cyclophosphamide and adoptively transferred immune syngeneic Lyt-1+2- lymphocytes. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1981;154:952–963. doi: 10.1084/jem.154.3.952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenberg PD, Kern DE, Cheever MA. Therapy of disseminated murine leukemia with cyclophosphamide and immune Lyt-1+,2- T cells. Tumor eradication does not require participation of cytotoxic T cells. J Exp Med. 1985;161:1122–1134. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.5.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Voskoboinik I, Thia MC, De Bono A, Browne K, Cretney E, Jackson JT, Darcy PK, Jane SM, Smyth MJ, Trapani JA. The functional basis for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a patient with co-inherited missense mutations in the perforin (PFN1) gene. J Exp Med. 2004;200:811–816. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singer GG, Abbas AK. The fas antigen is involved in peripheral but not thymic deletion of T lymphocytes in T cell receptor transgenic mice. Immunity. 1994;1:365–371. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dustin ML, Cooper JA. The immunological synapse and the actin cytoskeleton: molecular hardware for T cell signaling. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:23–29. doi: 10.1038/76877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reddy P, Maeda Y, Liu C, Krijanovski OI, Korngold R, Ferrara JL. A crucial role for antigen-presenting cells and alloantigen expression in graft-versus-leukemia responses. Nat Med. 2005;11:1244–1249. doi: 10.1038/nm1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones SC, Murphy GF, Friedman TM, Korngold R. Importance of minor histocompatibility antigen expression by nonhematopoietic tissues in a CD4+ T cell-mediated graft-versus-host disease model. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1880–1886. doi: 10.1172/JCI19427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anderson BE, McNiff JM, Jain D, Blazar BR, Shlomchik WD, Shlomchik MJ. Distinct roles for donor- and host-derived antigen-presenting cells and costimulatory molecules in murine chronic graft-versus-host disease: requirements depend on target organ. Blood. 2005;105:2227–2234. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu X, Gao JX, Wen J, Yin L, Li O, Zuo T, Gajewski TF, Fu YX, Zheng P, Liu Y. B7DC/PDL2 promotes tumor immunity by a PD-1-independent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1721–1730. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loke P, Allison JP. PD-L1 and PD-L2 are differentially regulated by Th1 and Th2 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5336–5341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931259100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liang SC, Latchman YE, Buhlmann JE, Tomczak MF, Horwitz BH, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. Regulation of PD-1, PD-L1, and PD-L2 expression during normal and autoimmune responses. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2706–2716. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mumprecht S, Schurch C, Schwaller J, Solenthaler M, Ochsenbein AF. Programmed death 1 signaling on chronic myeloid leukemia-specific T cells results in T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Blood. 2009;114:1528–1536. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-179697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.