Abstract

Iron deficiency in infancy negatively impacts a variety of neurodevelopmental processes at the time of nutrient insufficiency, with persistent central nervous system alterations and deficits in behavioral functioning, despite iron therapy. In rodent models, early iron deficiency impairs the hippocampus and the dopamine system. We examined the possibility that young adults who had experienced chronic, severe iron deficiency as infants would exhibit deficits on neurocognitive tests with documented frontostriatal (Trail Making Test, Intra-/Extra-dimensional Shift, Stockings of Cambridge, Spatial Working Memory, Rapid Visual Information Processing) and hippocampal specificity (Pattern Recognition Memory, Spatial Recognition Memory). Participants with chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy performed less well on frontostriatal-mediated executive functions, including inhibitory control, set-shifting, and planning. There was also evidence of impairment on a hippocampus-based recognition memory task. We suggest that these deficits may result from the long-term effects of early iron deficiency on the dopamine system, the hippocampus, and their interaction.

Keywords: Iron deficiency, development, memory, executive functioning

Iron-deficiency anemia impacts approximately 1-2 billion people worldwide. In developing countries, the prevalence among pregnant women and young children ranges between 23% and 50%.1-2 Although considerably less problematic in industrialized nations, infants are at increased risk everywhere, especially among poor, minority, and immigrant groups.3 Concerns about reducing the prevalence of iron deficiency exist not only because of its ubiquity, but also because of potential long-term negative effects on individual functioning4 with concomitant societal impact where iron deficiency is widespread.

Infants with iron-deficiency anemia or other indications of chronic, severe iron deficiency exhibit poorer functioning in the cognitive, affective, and motor domains. Before treatment, these infants receive lower scores on the Mental and Psychomotor Development Indexes (MDI and PDI, respectively) of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, relative to infants with better iron status.5-11 During behavioral testing, affected infants are coded as being more wary, hesitant, and easily fatigued than are infants with better iron status. In addition, they maintain closer contact with their mothers, display less positive affect, and are less playful and attentive.12 Iron therapy lasting between 2 and 6 months did not correct the differences in the majority of available studies.6,9,10,13

Longitudinal research efforts have also indicated that children who experienced chronic, severe iron deficiency in the first years of life manifest long-term challenges in the cognitive, affective, and motor domains. For example, children who had iron-deficiency anemia in infancy scored lower on learning achievement and measures of persistence, self-control, and attention at 7 years, relative to children with good iron status.14 In another sample, children who had chronic, severe iron deficiency as infants scored less well on components of the Woodcock-Johnson and on tests of visual-motor integration at 5 years.15 At 11-14 years, these same children achieved lower scores on tests of arithmetic and written expression, spatial memory, and selective recall relative to their peers with good iron status. They were also more likely to have repeated a grade in school or had parents who requested special educational services for them, such as tutoring.16 Children who had experienced severe iron deficiency as infants also manifested challenges in the affective and motor domains: they were more likely to have internalizing (e.g., anxiety and depression) and externalizing (e.g., delinquent behavior) problems in early adolescence,16 and they exhibited evidence of impaired motor skill at both the 5- and 11-14-year assessments.15-16 In addition, a longitudinal assessment of global cognitive functioning in these children at five time points up to 19 years of age indicated that socioeconomic status moderated the effects of chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy: affected participants who came from families of low socioeconomic status showed a widening gap in cognitive performance from infancy to young adulthood, whereas those who had iron deficiency and came from middle-class families did not.17

Chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy may impact neurodevelopment and behavior. Available iron may be prioritized to red blood cells over other organs early in life, including the brain.18 Depending on the time course of nutrient insufficiency, a number of brain functions may be negatively impacted at important points in development. The striatum and the hippocampus are two brain regions that undergo considerable maturation during the early postnatal period, and both have shown the effects of early iron deficiency in animal models.19-22 The striatum sends dopamine-rich projections to prefrontal cortex and is recruited in the control of executive functions such as inhibitory control, planning, sustained attention, and working memory, emotion regulation, memory storage and retrieval, motivation, and reward. The hippocampus, located in the medial temporal lobe, is involved in recognition, recall, and spatial memory (see review4).

Effects of Iron Deficiency on the Dopamine System

Animal models of chronic, severe iron deficiency show that a lack of sufficient brain iron early in life negatively impacts several neurodevelopmental processes, including myelination, dendritogenesis, synaptogenesis, neurotransmission, and neurometabolism, with long-term functional consequences (see review23). In the rat, diet-induced postnatal iron deficiency results in an elevation of extracellular dopamine (and a consequent reduction in dopaminergic activity) in the striatum by depleting the number and/or functionality of dopamine reuptake transporters and receptors,24-26 a consequence of early nutrient deficiency that persists into adulthood.23,27-28 The extensive connections between the striatum and other components of the three primary dopamine pathways (nigrostriatal, mesocortical, and mesolimbic29) suggests that the consequences of impaired dopamine function may extend to influence other brain regions. For example, dopamine is a known modulator of neural activity in circuits involving prefrontal cortex.29 Decreased dopamine binding30 or the application of dopamine antagonists to neurons in prefrontal cortex31-32 results in alterations of the characteristic neuronal response pattern32 and in the selective modulation of performance on tasks of executive function in nonhuman primates.31

Relations between reduced dopaminergic activity and performance on frontostriatal-dependent measures of executive functioning have also been documented in typically-developing human participants using dopamine receptor agonists and antagonists. Results from these investigations have shown that the administration of D2 receptor agonists facilitates performance on a spatial span task,33 whereas D2 receptor antagonists lead to impairments in planning, set-shifting, and spatial working memory.34-35 To our knowledge, the effects of chronic, severe iron deficiency on the dopamine system have not yet been investigated in humans using tasks with documented frontostriatal specificity. However, the behavioral effects of dopamine depletion on measures of executive function in nonhuman primates and humans, paired with rodent data indicating the long-term effects of chronic, severe iron deficiency on dopamine receptors, transporters, and extracellular concentrations provides a theoretical basis for examining the effects of chronic, severe postnatal iron deficiency on tests of striatal and prefrontal integrity in adulthood.

Effects of Iron Deficiency on Medial Temporal Lobe Structures

Iron deficiency experienced during the late prenatal-early postnatal period also exerts deleterious effects on hippocampal neurodevelopment. A rat model of perinatal iron deficiency shows significant alterations in hippocampal neurometabolism, structural morphology, and electrophysiology of affected pups that persist into young adulthood despite iron repletion. For example, elevations in select hippocampal neurometabolites after the induction and treatment of early iron deficiency indicate downregulation of cellular metabolism, abnormal patterns of dendritic arborization and synaptogenesis, and hypomyelination.20,22 Indeed, further investigation of the effects of perinatal iron deficiency on dendritic outgrowth indicated long-term alterations in structural morphology (i.e., tangled branches that were shorter and less well-organized than those of control animals36) and electrophysiology that remained into adulthood despite the initiation of iron therapy shortly after birth.37 Indeed, these long-term neurodevelopmental compromises likely contribute to the poorer performance of formerly iron deficient animals on hippocampus-based tasks of learning and memory, such as the Morris water maze19,21,38 and trace fear conditioning,39 relative to animals with good iron status.

Long-term deficits in hippocampal functioning are also related to prenatal iron deficiency in the human, as indicated by studies of infants of diabetic mothers. Infants of diabetic mothers are at increased risk for brain iron deficiency. Those with very low cord blood ferritin levels show deficits in tests of auditory recognition memory at birth,40 visual recognition memory at 6 months of age,41 cross-modal matching at 8 months,42 and explicit or declarative memory at 12 months43 and 36 months.44 Postnatal dietary iron deficiency may exert similar effects on the hippocampus: using event-related potentials, infants who had iron-deficiency anemia appeared to show a developmental delay in recognition memory, such that their electrophysiological profiles at 12 months resembled those of iron-sufficient infants tested in the same procedure at 9 months.45

Effects of Iron Deficiency on Other Neurodevelopmental Processes

The neurobiological effects of chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy undoubtedly extend beyond striatal, prefrontal, and hippocampal systems. There is evidence of effects on the mesolimbic dopamine system, which regulates affect, reward, and exploration,21 and the nigrostriatal dopamine system, which is critically involved in movement and other aspects of motor control.19,21 One particularly ubiquitous effect of chronic, severe iron deficiency on neurodevelopment is hypomyelination, likely due to impaired oligodendrocyte function with consequent alterations in myelin-related lipids and phospholipids that may impact myelin compaction.20 Hypomyelination has been proposed as the explanation for why infants who experienced chronic, severe iron deficiency had longer latencies for auditory evoked potentials after iron therapy as compared to infants who had good iron status.46 Notably, these effects were not transient: children who had chronic, severe iron deficiency as infants also manifested longer latencies for visual and auditory evoked potentials as compared to controls at 4 years of age.47 Hypomyelination may also contribute to iron-related delays in cognition. For example, for the same degree of novelty preference, infants who did not receive supplemental iron in a preventive trial spent more time examining novel stimuli during the Fagan Test than did infants who received additional iron,48 thereby indicating that a lack of iron may impair processing speed. To the extent that the Fagan Test is a good predictor of long-term cognitive abilities, slower processing speed may be an expected persistent consequence of chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy.

The Present Study

The only available longitudinal study that extends into young adulthood recently reported a widening gap on global cognitive tests 17-18 years after treatment for chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy, especially for individuals of low socioeconomic status.17 Notably, however, significant or marginal differences in performance on global cognitive measures at 19 years were also found by iron status in infancy after controlling for socioeconomic status.49 The present study concerns the effect of early iron deficiency on specific tests of neurocognitive function in the same cohort at 19 years. Such an investigation is important, in that neurocognitive assessments may provide information as to which specific brain regions and processes may be impacted by early iron deficiency and insight as to the particular functional deficits that underlie performance on global tests. The test battery highlighted behaviors subserved by striatum, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus due to their known vulnerability to iron deficiency.

Our primary hypothesis was that young adults who had experienced chronic, severe iron deficiency as infants would manifest difficulty with behaviors dependent on the striatum and its connections with prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus, especially as the problems recruiting these systems became more complex. Due to iron deficiency-related effects on the dopamine system, we predicted poorer performance on frontostriatal tasks of inhibitory control, set-shifting, planning, selective attention, and working memory. We also expected young adults who had experienced chronic, severe iron deficiency to have difficulty with hippocampus-based recognition memory tasks, especially those that elicited frontostriatally-mediated executive functions as well.

METHOD

Participants

Potential study participants were screened through door-to-door contact in Hatillo, Costa Rica between 1981 and 1983. Parents provided information about the health and development of their infants and consented to blood tests to determine the iron status of their infant. Healthy 12- to 23-month-olds participated in a study concerning the impact of iron status in infancy and iron therapy for affected individuals on functional outcomes. Infant participants were born at term, had no physical abnormalities or developmental delays, and were growing normally by U.S. standards (see reference9 for more complete inclusion criteria).

Iron status in infancy was determined by venous concentrations of hemoglobin, transferrin saturation, free erythrocyte protoporphyrin, and serum ferritin. Iron deficiency was defined as two or more abnormal iron measures (a serum ferritin concentration of < 12 ng/mL [<270 pmol/L] and either a free erythrocyte protoporphyrin level of ≥ 100 μg/dL [≥ 1.77 μmol/L] of red blood cells or a transferrin saturation of < 10%).50-52 Iron sufficiency was defined as a hemoglobin concentration of 12.0 g/dL or more and normal values on all iron status measures. Hematologic response to iron therapy in infancy was excellent, with a mean hemoglobin increase of 3.7 g/dL among iron deficient infants with a hemoglobin concentration of 10.5 g/dL or less. Anemia in all infants resolved following three months of iron therapy, but as might be expected, those with indications of severe or chronic iron deficiency still had biochemical alterations, such as elevated erythrocyte protoporphyrin values.9 At the subsequent follow-ups that included blood collection (5 years;15 11-14 years,16 and 19 years), iron deficiency was present in less than 5% of the sample, and no one had iron deficiency anemia except for 4 women at 19 years, 2 of whom were pregnant. These data indicate that the Costa Rican diet at the time provided adequate iron to correct any iron parameters that were still altered after treatment in infancy and to maintain good iron status thereafter.

Following the approach taken in the 5-year and subsequent reports,15-17 we compared participants who had chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy (with or without anemia) with the rest of the sample who were iron sufficient before and/or after iron therapy in infancy. For simplicity, the iron sufficient participants will be referred to as “good iron status.” The chronic, severe iron deficient group consisted of participants who had marked iron deficiency anemia in infancy (hemoglobin ≤ 10.0 g/dL) and those with higher hemoglobin concentrations and iron deficiency that did not fully correct after 3 months of iron therapy. Analyses compared the chronic, severe iron deficient (n = 33) and good iron status (n = 81) groups.

Measures and Procedures

Trail Making Test

The Trail Making Test53 was one of the tests of frontally-mediated executive processes. In Part A, subjects drew lines between numbered circles in consecutive order (1, 2, 3… 23, 24, 25) as quickly as possible on a standard piece of paper. Immediately thereafter, participants completed Part B of the task, in which they rapidly drew lines connecting alternating numerical and alphabetical stimuli (1, A, 2, B… 12, L, 13). In accord with the standard administration of the task, participants were made aware of errors immediately after they occurred and were allowed to modify the direction of the incorrect line.54 Both Parts A and B of the task require visual-motor integration and the ability to selectively identify target locations. However, the increased demands of Part B (including the lengthier distance between target locations and the greater amount of visual interference on the page55) elicit frontostriatally-mediated executive processes. Specifically, Part B of this task has been suggested to assess between-subject variability in the ability to concurrently process two types of stimuli54,56 and/or the ability to switch tasks or alternate between different response sets.57 Indeed, individuals with documented frontal lobe damage are more likely than unaffected controls to make errors on Part B but perform equally well on Part A.58

The primary dependent variables related to errors and time to completion. Error measures included errors on Part A, errors on Part B (switching, non-switching, and total errors), and total errors on Parts A and B. On Part B, switching errors occurred when participants failed to successfully alternate between numbers and letters (e.g., they drew a line from number-number or letter-letter, such as 1-A-2-3). Non-switching errors were noted when participants correctly alternated between numbers and letters but failed to select the appropriate target (e.g., 1-A-2-C). Time measures included time to complete Part A, time to complete Part B, time to complete Part B accounting for time to complete Part A, the ratio of time to complete Part B divided by time to complete Part A, and time to complete Parts A and B.

Cambridge Automated Neuropsychological Test Assessment Battery (CANTAB)

To further assess the integrity of frontally-mediated functions and pursue the possibility of long-term effects of early iron deficiency on medial temporal lobe structures, we employed the CANTAB (Version 3; www.cambridgecognition.com). The CANTAB, which was largely developed based on animal studies, includes tasks that are differentially sensitive to frontal and temporal lobe development and dysfunction. Although initially used to assess the neurological declines characteristic of degenerative diseases in adult samples (e.g., Parkinson’s disease59-60, the CANTAB has also proven instrumental in charting the progression of frontally- and temporally-mediated abilities in typically developing populations61-62 and in samples of children with psychiatric conditions, such as autism or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD63). The CANTAB has also been used to elucidate effects of psychopharmacological agents on the cognitive performance of participants with neurological disorders (e.g., dopaminergic medication on patients with Parkinson’s disease64).

In the present study, participants were tested on 9 of the 13 subtests of the CANTAB. We included the Motor Screening Test, three tests of visual recognition memory (Delayed Match to Sample, Pattern Recognition Memory, and Spatial Recognition Memory), three tests of working memory, planning, or executive function (Intra-/Extra-dimensional Shift, Stockings of Cambridge, and Spatial Working Memory), and two tests of visual attention (Reaction Time and Rapid Visual Information Processing). These tests and their neural correlates are detailed below. Additional information is not provided on Delayed Match to Sample, however, as procedural error unfortunately precluded its analysis and interpretation. The tests were administered in the order mentioned above, and test order was held constant across all participants.

Measures of Basal Ganglia-Dependent Motor Performance

Motor screening test (basal ganglia, corticostriatal circuitry65)

This task is designed to familiarize participants with the testing apparatus and screen for visual-motor impairments that might confound the interpretation of latency measures on the other more cognitively demanding tests. Participants were asked to touch the center of an X-like stimulus as it appeared on the screen in different locations. Ten test trials were administered; mean response latency to touch the appropriate location was the dependent measure.

Reaction time (basal ganglia; dopamine and ascending catecholamine systems66)

This task assesses reaction time to touch a yellow circle on the screen under different response demands. In the single-choice reaction and movement time task, participants placed their fingers on a touch-pad until a yellow circle appeared in the center of the screen, at which point they removed their fingers from the pad (reaction time) and touched the circle (movement time). In the five-choice reaction and movement time task, the touch-pad manipulation was again imposed, but the circle appeared at any one of five locations on the screen. The primary measures for single- and five-choice problems were latency to release the touch-pad and movement time to touch the circle.

Measures of Frontostriatal-Dependent Executive Functions

Stockings of Cambridge (prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate, right caudate nucleus, posterior parietal regions59)

This task is designed to assess planning abilities and behavioral inhibition.67 Participants viewed a computer screen that was split into two halves. The top row of the display served as a demonstration and contained three hanging stockings of various lengths that could differentially accommodate three balls: from left to right, the stockings could fit three balls, two balls, and one ball, respectively. The bottom portion of the display was identical to the top row in terms of the number of stockings and their ability to accommodate balls; the only difference was the position of the balls in the stockings. Participants were asked to replicate the position of the balls shown in the top portion of the display by touching the desired ball followed by its new location. The critical constraints were that only balls at the top of a stocking could be moved to new locations and that each problem was to be completed in a certain minimum number of moves (2, 3, 4, or 5). The primary dependent measures from this condition were the number of moves required to successfully complete 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-move problems and the total number of problems solved in the minimum number of moves.

Participants also completed a yoked control condition that allowed for the dissociation of movement times from the amount of time spent thinking before attempting to solve each problem. After completing the problems involved in the assessment of planning and inhibition, the computer modeled the actions that the participant completed for each problem, one ball at a time. The participant was instructed to copy the movements made by the computer. As a result, the only difference between the two conditions was the time required to plan moves in the first condition; both tasks necessitated visual-motor integration and the execution of movements. Latencies obtained from both conditions allowed for the derivation of two additional measures: mean initial thinking time was computed by subtracting the time to select the first ball in the yoked control condition from the same measure obtained in the experimental condition; mean subsequent thinking was computed by subtracting the difference in time between selecting the first ball and completing the problem in the yoked control condition from the same measure obtained in the experimental condition, divided by the number of moves required to solve the problem.

Intra-/Extra-dimensional Shift (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex for performance on the extra-dimensional shift, orbitofrontal cortex for reversals68)

This task is designed to measure the ability to shift attention to relevant dimensions of complex visual stimuli based on computer-generated feedback (see reference60 for a complete description). Participants viewed two different stimuli on the screen. Initially, stimuli consisted of either purple shapes or white lines separately enclosed in square white boxes; both stimuli were of the same type. Participants were told that one of the two items was correct and the other was incorrect, but only the computer was aware of the rule. The experimenter indicated to the participants that their first choice would be random, and the computer would indicate to them whether their selection was correct or incorrect. Participants were told that they would continue selecting stimuli and receiving feedback regarding the accuracy of their responses until they demonstrated that they had figured out the rule, at which point it would be changed. Participants met the learning criterion when they made 6 consecutive correct selections. Participants were allowed 50 trials to achieve the learning criterion before the test was terminated.

The task was separated into nine distinct stages. In the first stage (simple discrimination), participants were presented with either two purple patterns or two white lines displayed in white boxes. Although the same type of stimulus was shown on a given trial (patterns or lines), the particular shapes and orientations of the lines varied. In the second stage (simple reversal), the rule changed such that the previously incorrect stimulus became correct.

The third stage (compound discrimination with non-overlapping stimuli) allowed for the inclusion of the other type of stimulus in addition to those that had been tested previously (e.g., if the participant was tested with shapes in the first two stages, lines were also included in the boxes as well). Although present in the same box, the stimuli did not overlap. Moreover, the rule from the previous stage did not change, such that the stimulus that was correct during the simple reversal stage was again correct in compound discrimination with non-overlapping stimuli. This stage was primarily included to facilitate performance on the next stage of the task (compound discrimination with overlapping stimuli), as participants often experience difficulty performing well with overlapping stimuli without this intervening stage (pilot data mentioned, but not presented, in reference60).

In the fourth stage (compound discrimination with overlapping stimuli), participants were presented with overlapping versions of the stimuli used in the previous stage (white lines were always presented in front of purple shapes). The same response contingencies held from the previous stage, such that participants were expected to respond to the same item that had been meaningful in compound discrimination with non-overlapping stimuli. The fifth stage (compound discrimination reversal with overlapping stimuli) modified the response contingency, such that the opposite item from the same stimulus category became correct (e.g., if one of the purple shapes was correct on the previous stage, the other purple shape became correct).

The sixth stage (intra-dimensional shift) was the first that introduced new exemplars of overlapping stimuli. Despite the change in stimuli, the relevant stimulus dimension remained unchanged from the previous stage: that is, if participants were previously responding to one of the purple shapes, the correct response was again based on shape, but the participant had to successfully determine which of the two new stimuli was correct. The seventh stage (intra-dimensional reversal) involved a modification of relevant stimulus dimensions. For example, if participants were successfully responding to one of the two purple shapes on the previous stage, the correct response on the intra-dimensional reversal stage involved choosing the other purple shape.

The final two stages of the task involved an extra-dimensional shift and a reversal of that contingency. The eighth stage (extra-dimensional shift) also included the introduction of new exemplars of each stimulus type. However, contrary to the rule that was imposed at the intra-dimensional shift stage (where the same type of item that was correctly responded to at the previous stage served as correct), the correct item in the extra-dimensional shift was one of those other than the one that had been previously rewarded. That is, if shapes were rewarded at the intra-dimensional shift and reversal stages, lines became the relevant dimension. Participants had to determine which of the two new stimuli was correct by trial-and-error. At the reversal stage, the other stimulus of the same type became correct. Dependent measures included the number of errors made on all stages before the intra-dimensional shift, the number of errors made on the final four stages of the task (intra-dimensional shift, intra-dimensional reversal, extra-dimensional shift, and extra-dimensional reversal), and the proportion of participants who attempted and passed each stage.

Spatial working memory (dorsal and ventral prefrontal cortices; ascending catecholamine, dopamine systems69-70)

This task is designed to assess working memory for locations.71 Participants were instructed to find small blue tokens hidden in colored boxes in various locations on the screen. On any given trial, 4, 6, or 8 boxes were distributed across the screen; a black column located at the bottom right of the screen served as a depository for the tokens. Participants were told that each box held only one token per trial, and they were made aware that they had to find enough tokens to fill the depository completely. Task difficulty increased across trials, such that participants had to complete 4 trials successively at each level of difficulty (4, 6, and 8 boxes) before moving onto the next level. The colors and positions of the boxes also changed across trials to prohibit the use of repeated search patterns. Dependent measures concerned the number and type of errors made while searching (e.g., between errors, defined as returning to a box where a token has been previously recovered, and within errors, which included returning to search a box that was previously discovered to be empty).

The CANTAB also derives a score pertaining to the use of search strategies on this task. The use of successful search strategies reduces memory load for which boxes have been searched previously, thereby allowing for more efficient performance. One possible means of successfully searching for hidden tokens is to initiate each search within a trial at the same location, eliminating the search of boxes where tokens have been found previously.72-73 The strategy use score indicates how often participants initiated searches from the same location for 6- and 8-box problems. A low score represents efficient use of this technique, indicating that participants consistently started their search at the same location; high scores suggest that participants chose boxes at random.

Rapid visual information processing (frontal gyri, parietal cortex, fusiform gyrus74)

This task is designed to measure sustained attention with an additional working memory component. Participants viewed sequences of numbers presented in a white box in the center of the screen. The numbers ranged in value from 2 to 9 and appeared at a rate of one every 600 ms. Participants were instructed to detect each occurrence of specific odd or even target sequences (including 3-5-7, 5-7-9, 2-4-6, and 4-6-8) by pressing the touch-pad within 1800 ms after the appearance of the last digit. Numbers were presented for 4 minutes; target sequences occurred approximately once every 7500 ms. The primary dependent measures were the number of hits (correctly identifying a specified sequence of numbers in the appropriate time limit), misses (failing to identify a specified sequence of numbers, either by not recognizing it as such or by responding after the time limit had expired), correct rejections (correctly failing to respond to sequences presented in the wrong order), and false alarms (incorrectly identifying a sequence as correct). Mean time to identify a correct sequence was also analyzed.

Measures of Medial Temporal Lobe-Dependent Recognition Memory

Pattern recognition memory (medial temporal lobe;70 fornix, thalamus, ventromedial prefrontal cortex75)

This task is designed to assess the ability to recognize visual patterns after a delay. Participants viewed the consecutive presentation of 12 complex, colored geometric patterns in the middle of the touch screen; each pattern was presented for 3 seconds. After the presentation of the last pattern, the computer imposed a 5 s delay before initiating the test phase. In the test phase, pairs of familiar and novel patterns were presented on the screen, and participants were asked to touch the one they had seen previously. Feedback was provided by the program after each selection to indicate the accuracy of the response. After the recognition test was completed for the first 12 patterns, the presentation and test protocols were administered again, thereby allowing for recognition testing of 24 novel stimuli. The primary dependent measures were the percent of correct responses and time to make correct responses, analyzed across all 24 trials.

Spatial recognition memory (medial temporal lobes; right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex76)

This task is designed to assess memory for locations. Participants viewed the successive presentation of 5 white boxes at different locations on the screen; each box was shown for 3 s. After the presentation of the final box, the computer imposed a 5 s delay before initiating the test phase. In the test phase, two boxes were presented on the screen: one box was shown at a familiar location and another was shown at a novel location. Participants were instructed to select the box shown at the familiar location. The program provided feedback after each response. Participants completed 4 blocks of 5 trials each, allowing for a total of 20 responses. The dependent variables included the percent of correct responses and time to make correct responses, computed across all 20 trials.

Stimulus-Response Incompatibility

The Stimulus-Response Incompatibility task indicates participants’ ability to inhibit incorrect responses when presented with incompatible pairs after having previously responded to highly compatible stimulus-response pairs that require relatively automatic, intuitive responses.77 Participants were presented with an arrow pointed to either their left or their right. In the compatible condition, participants were instructed to press a specific key on the left side of the keyboard when the arrow pointed left and to press a specific key on the right side of the keyboard when the arrow pointed right. Immediately thereafter, participants were tested in an incompatible condition. They were instructed to press a specific key on the left side of the keyboard when the arrow pointed right and to press a specific key on the right side of the keyboard when the arrow pointed left. The compatible condition was always administered before the incompatible condition. Participants completed 20 practice trials of each type before completing 50 test trials. Each arrow was presented in the center of the screen for 10 s and was preceded by a fixation cross shown for 1 s.

Statistical Analyses

The primary methods of analysis followed the generalized linear model. Between-subjects analyses involving iron status in infancy, growth curve analyses involving factors of iron status with repeated measures on neurocognitive variables of interest, and analyses to establish whether performance on one dependent measure significantly interacted with iron status to predict outcome on another were conducted using SAS PROC GENMOD. When the distribution of the count-based outcome variables was not normal, the data were fit using Poisson models. The use of Poisson distributions requires that the data are transformed into a logarithmic scale for analysis. These log values were then re-transformed back to their original means and standard errors were approximated using the delta method. Regression analyses were conducted using binomial distributions; logistic regressions were used to evaluate significant differences by iron status for categorical variables.

Conceptually and statistically significant covariates were included in analyses of continuous outcomes based on their correlation with them. Background variables obtained in infancy are shown in Table 1 for the participants tested in the neurocognitive battery at 19 years. Maternal IQ was assessed using a Spanish version of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS78); the quality of the participant’s home environment was measured using the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment Inventory (HOME79); and socioeconomic status was assessed using the Hollingshead Four-Factor Index.80 Socioeconomic status was included as a possible covariate because of the reported relations between this factor and neurocognitive outcomes81 and because preliminary analyses indicated that iron status in infancy and socioeconomic status interacted to predict performance on some neurocognitive measures. All variables were initially considered as potential covariates if they correlated with at least two dependent measures for a given test at p ≤ .10. The one exception to this rule concerned the Motor Screening subtest of the CANTAB. Because this subtest included only one dependent measure, all background variables that correlated with it were considered for inclusion as covariates. When two or more highly correlated background factors correlated significantly with outcome measures on the same test, only one of them was included as a covariate. The background variable that correlated with a greater number of dependent variables was included. If the number of significant correlations for background variables showing co-linearity was approximately equal, the background variable for inclusion was chosen either on conceptual (i.e., the most meaningful) or empirical (i.e., the most parsimonious model) grounds. To determine whether overall intellectual level mediated the effects of iron status on neurocognitive performance, a secondary set of analyses included a factor of concurrent IQ, as measured by an abbreviated version of the WAIS. Results from these analyses are reported when the inclusion of concurrent IQ eliminated significant or marginal effects that were otherwise apparent.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics at Study Enrollment by Iron Status in Infancy

| Good Iron Status (N = 33) |

Chronic, Severe Iron Deficiency (N = 81) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (months) ‡ | 17.3 ± .4 | 15.9 ± .6 |

| Birth weight (kg) ■ | 3.27 ± .04 | 3.14 ± .06 |

| Sex (% male) ‡ | 41% | 63% |

| Breastfed (% yes) | 96% | 88% |

| Age of weaning from breast (months) | 7.0 ± .6 | 5.5 ± .1 |

| Amount of milk or formula per day (ounces) | 27.8 ± 1.2 | 29.4 ± 1.9 |

| Age of introduction of cow milk (months) | 7.7 ± 2.0 | 9.0 ± 3.0 |

| Number of bottles per day | 3.6 ± .2 | 4.0 ± .2 |

| Mother’s education (years) | 9.7 ± .3 | 8.7 ± .5 |

| Mother’s IQ ● | 86.2 ± 1.3 | 77.3 ± 2.1 |

| Father present (% yes) | 78% | 67% |

| Grandparents present (% yes) ■ | 36% | 53% |

| HOME scores ● | 31.3 ± .7 | 26.9 ± 1.1 |

| Hollingshead scores | 29.9 ± 1.2 | 28.2 ± 1.9 |

| Participant IQ ■ | 87.4 ± 1.4 | 82.6 ± 2.3 |

Significant differences are indicated as follows: p < .01

p < .05

p ≤ .10

All chosen covariates were initially entered into a given model. Statistically non-significant covariates were then removed by successively eliminating the most non-significant variables until the model contained only covariates that were significant at p ≤ .10. All analyses that yielded significant results were then inspected for the presence of outliers, defined as values that were ± 2½ standard deviations from the mean, based on the overall distribution. Outlying values were truncated to the highest or lowest acceptable value in the distribution, and the analysis was conducted again (the choice was made to truncate values, instead of eliminating them completely, so as to maintain the integrity of the longitudinal dataset). In addition, when repeated measures analyses were conducted, highly non-significant interactions (p ≥ .25) between iron status and the repeated variable were eliminated from the model, which was then re-analyzed to examine the independent effects of iron status on the outcome measure of interest. Corrections were not made for multiple comparisons because of the hypothesis-driven nature of the investigation and following the argument that all obtained results be reported, with meaningful patterns interpreted further and left for corroboration through replication.82

Results with truncated data values and relevant covariate control are presented. Additional information regarding analyses without covariates, the specific covariates included in each analysis, or outcomes of analyses related to task performance independent of iron status may be obtained from the first author.

Results

Trail Making Test

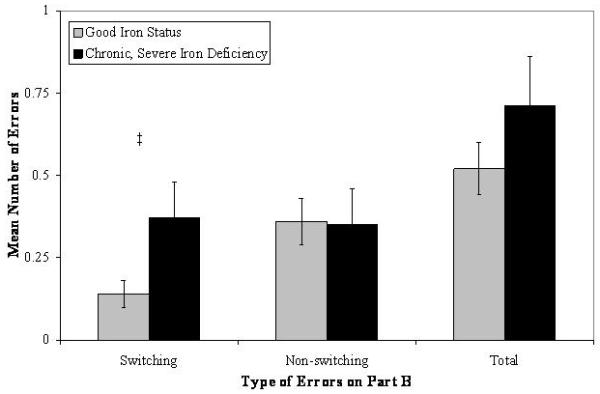

There were no differences on Part A, indicating a lack of between-group differences in motor and visual speed and control processes. As shown in Figure 1, however, young adults who had chronic, severe iron deficiency as infants made a greater number of switching errors relative to young adults with good early iron status: χ2(1, N = 110) = 4.22, p < .04, d = .54. A supplementary logistic regression indicated that participants who had chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy were more likely to make at least one switching error on Part B relative to young adults who had good iron status: χ2(1, N = 111) = 6.23, p < .01, odds ratio = 3.45. Group differences were not found on non-switching errors or total errors made on Part B or time to completion variables.

Figure 1.

Number of switching, non-switching, and total errors made on Part B of the Trail Making Test as a function of iron status in infancy (‡ p < .05).

CANTAB

Measures of Basal Ganglia-Dependent Motor Performance

Motor screening and reaction time

There were no significant group differences on mean latency to touch the target in the appropriate location in the Motor Screening subtest or in reaction or movement times for single or five-choice problems in the Reaction Time subtest. Therefore, latency differences related to iron status on the other more cognitively demanding tasks that follow are not attributed to a general slowing of motor responses resulting from early iron deficiency.

Measures of Frontostriatal-Dependent Executive Functions

Stockings of Cambridge

Growth curve analyses were used to compare the iron status groups in initial and subsequent thinking time and in the number of moves required to successfully solve 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-move problems. All of the data were fit to normal distributions.

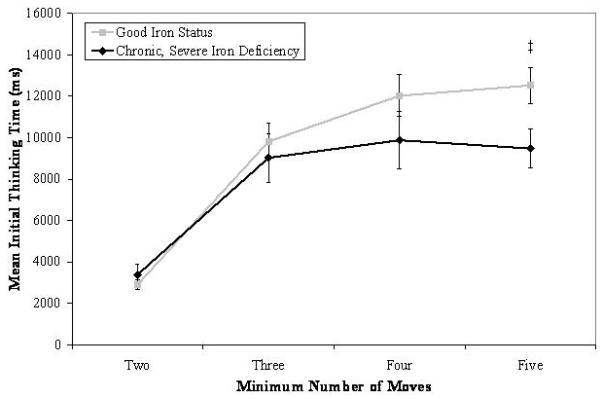

There was a marginal interaction between iron status and problem difficulty on mean initial thinking time: χ2(3, N = 456) = 7.33, p = .06. As shown in Figure 2, young adults with good iron status in infancy showed increases in initial thinking time from 2- to 3- and from 3- to 4-move problems, whereas young adults who had experienced chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy showed increases in thinking time from 2- to 3-move problems but devoted similar amounts of planning time to 3-, 4-, and 5-move problems. Further examination of differences by iron status at each level of problem difficulty revealed a significant group difference for 5-move problems, such that participants with good early iron status spent a greater amount of time planning their first move relative to participants who had chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy: χ2(1, N = 456) = 5.42, p < .02, d = .46.

Figure 2.

Mean initial thinking time as a function of iron status in infancy and problem difficulty on the Stockings of Cambridge subtest of the CANTAB. Significant group differences for a given level of problem difficulty are indicated (‡ p < .05).

We investigated the possibility that young adults who had experienced chronic, severe iron deficiency as infants compensated for their lack of initial planning time by increasing the amount of time devoted to planning subsequent moves. Although a marginal interaction was found between iron status and problem difficulty: χ2(3, N = 456) = 6.53, p = .09, differences in subsequent thinking time were not found by group as a function of problem difficulty. The same general pattern of subsequent thinking was not maintained across both groups of participants, however. Young adults who had good iron status increased their subsequent thinking time as the problems became more challenging, but participants who had chronic, severe iron deficiency as infants did not do so for the shift from 2- to 3-move problems and only showed marginal increases in subsequent planning time from 4- to 5-move problems (a significant increase in thinking time was apparent for these participants from 3- to 4-move problems). These results, taken together with those indicating less initial planning time by young adults who had experienced chronic, severe iron deficiency, indicates that they did not “catch up” in terms of planning time by devoting greater amounts of thinking time before initiating subsequent movements.

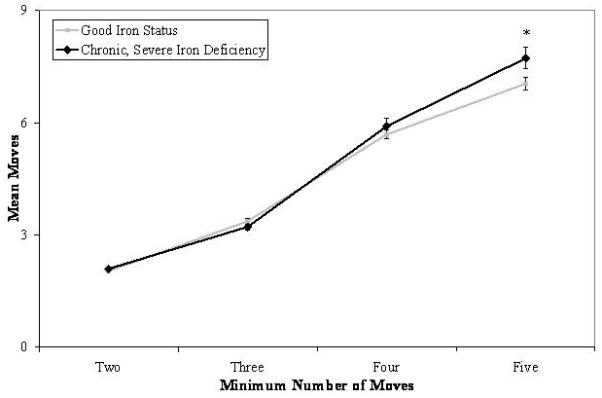

The number of moves required to solve 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-move problems was analyzed to determine whether variability in initial thinking time related to overt behavioral performance. A marginal interaction was found between iron status and problem difficulty: χ2(3, N = 456) = 6.89, p = .08. As shown in Figure 3, both groups required more moves to successfully solve each problem as difficulty level increased. There was a significant effect of group for 5-move problems, such that young adults who had experienced chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy required a greater number of moves to solve the most difficult problem relative to participants with good early iron status: χ2(1, N = 456) = 4.10, p < .04, d = .41. Controlling for concurrent IQ reduced the significance level of the interaction to .20 and that of the group difference for 5-move problems to .11. There were no differences by iron status group in the number of problems solved in the minimum number of moves.

Figure 3.

Mean number of moves required to successfully solve problems as a function of iron status in infancy and problem difficulty on the Stockings of Cambridge subtest of the CANTAB. Significant group differences for a given level of problem difficulty are indicated (‡ p < .05).

Additional analyses indicated that the group differences in mean initial thinking time and mean moves on 5-move problems did not result from a speed-accuracy tradeoff. First, there were no significant or marginal correlations between these two variables for 5-move problems. Second, additional analyses were conducted for mean initial thinking time and mean moves on 5-move problems after statistically controlling for the other variable. In both cases, these covariates were highly non-significant and were removed from the models, indicating that they did not contribute to performance on the other measure. These effects were unaltered by the inclusion of concurrent IQ as an additional covariate.

Intra-/Extra-dimensional Shift

Between-subjects analyses were used to determine whether the number of errors made on all stages before the intra-dimensional shift differed as a function of iron status in infancy for participants who successfully completed the final stage of testing. Additional analyses used growth curves with Poisson distributions to compare performance across the final four stages of the task (intra-dimensional shift, intra-dimensional reversal, extra-dimensional shift, and extra-dimensional reversal). Young adults who had good iron status in infancy made a greater number of errors on all stages preceding the intra-dimensional shift (M = 5.98, SE = .05) relative to individuals who had chronic, severe iron deficiency as infants (M = 4.06, SE = .09): χ2(1, N = 62) = 9.68, p < .002, d = .83. There were no differences in the number of errors made on the final four stages of the task by iron status group after removing the highly non-significant interaction from the models.

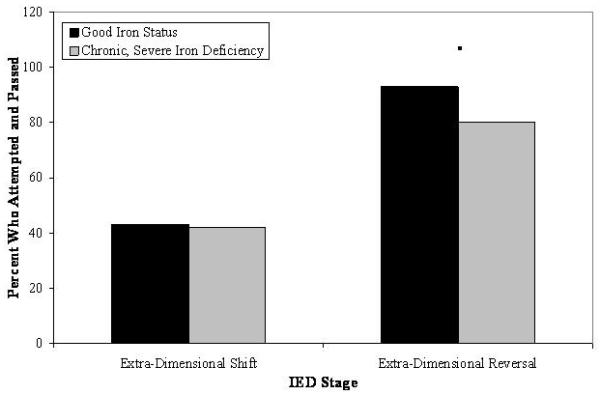

Logistic regressions were also computed to determine the proportion of participants who attempted and passed each stage by iron status. All participants successfully completed the first seven stages of the task. Variability in performance was apparent on the eighth stage (extra-dimensional shift), but there were no significant group differences. However, as shown in Figure 4, group differences were suggestive on the ninth (extra-dimensional reversal) stage of the task: there was a trend for a greater probability of participants with good iron status to attempt and pass this stage relative to those who had chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy: χ2(1, N = 69) = 2.71, p = .10, odds ratio = 3.83.

Figure 4.

Predicted probability of participants who attempted and passed the final two stages of the Intra-/Extra-dimensional Shift task of the CANTAB as a function of iron status in infancy. Marginal group differences are indicated (■ p = .10).

Spatial working memory

Growth curve analyses with Poisson distributions were used to compare performance on between and within errors made on 4-, 6-, and 8-box problems by iron status. There were no significant or marginal main effects of iron status after removing the highly non-significant interaction from the models. An independent between-subjects analysis concerning strategy use on 6- and 8-box problems also did not reveal any significant or marginal group differences.

Rapid visual information processing

There were no differences by iron status in infancy on signal detection measures of the number of hits, misses, false alarms, and correct rejections using Poisson distributions or on the mean latency to identify a correct sequence using a normal distribution.

Measures of Medial Temporal Lobe-Dependent Recognition Memory

Pattern recognition memory

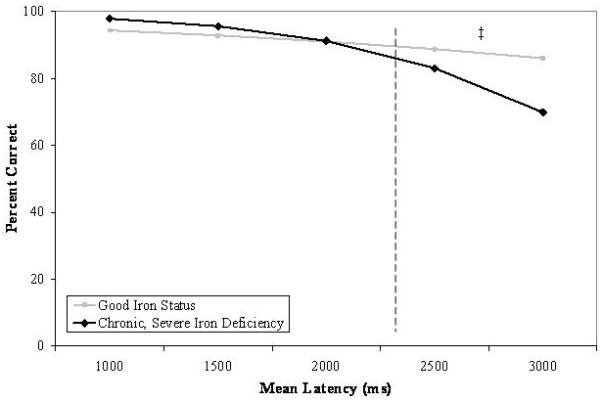

Regression analyses indicated that iron status groups significantly predicted the percent of correct responses: χ2(1, N = 110) = 10.41, p < .001, an effect that was qualified by an interaction with latency: χ2(1, N = 110) = 12.76, p < .0004. As shown in Figure 5, follow-up regression analyses indicated that response times greater than 2300 ms were predictive of fewer correct responses for participants who had chronic, severe iron deficiency (78% correct) in infancy relative to participants with good iron status (88% correct): χ2(1, N = 28) = 12.45, p < .03; differences by iron status were not apparent at latencies less than 2300 ms (94% and 91% correct for participants in the chronic, severe iron deficient and good iron status groups, respectively). There were no group differences on the percent of patterns identified correctly or on the latency to make correct responses.

Figure 5.

Predicted relations between mean latency to make correct responses and the percent of correct responses as a function of iron status in infancy on the Pattern Recognition Memory subtest of the CANTAB. Significant group differences are indicated (‡ p < .05).

Spatial recognition memory

There were no differences by iron status in percent of locations remembered, latency to make correct responses, or in the ability to differentially predict correct responses from iron status or its interaction with latency.

Stimulus-Response Incompatibility

There was no evidence of differential performance as a function of iron status in infancy on measures of errors or reaction time to complete compatible or incompatible trials.

Discussion

This study assessed the long-term effects of chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy on a battery of tasks mediated by frontostriatal and medial temporal lobe structures. When compared to young adults who had good iron status in infancy, participants who had chronic, severe iron deficiency experienced difficulty on tests involving inhibitory control, set-shifting, and planning, all of which are classified as executive functions and rely on the integrity of frontostriatally-mediated circuits. Participants who had chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy also performed less well on a hippocampus-based test of pattern recognition memory at longer self-imposed response latencies.

Measures of Frontostriatal-Dependent Executive Functions

Young adults who had chronic, severe iron deficiency as infants made more switching errors on Part B of the Trail Making Test relative to young adults with better iron status after treatment in infancy. We suggest that the increased number of switching errors on Part B (failing to successfully alternate between numbers and letters, ultimately drawing a line from number-number or letter-letter) resulted from the inability to shift between the task requirements of Parts A and B or from difficulty inhibiting the response pattern that was initially correct in Part A (where connecting lines from number-number was the desired action, and the only one that could be performed). Group differences were not expected on non-switching errors (i.e., successfully alternating between numbers and letters, but failing to select the appropriate target of the line), as the commission of these types of errors likely does not reflect deficits in set-shifting or inhibitory control to the same extent as switching errors.

Additional evidence of impairments in set-shifting associated with early iron deficiency was suggested by the Intra-/Extra-dimensional Shift task of the CANTAB. Specifically, a smaller proportion of participants who had experienced chronic, severe iron deficiency as infants attempted and passed the final extra-dimensional reversal stage relative to participants with good early iron status. Children and adults typically experience little difficulty completing the first five stages of the set-shifting task, with critical comparisons across groups often concerning performance on the final four stages (intra-dimensional shift, intra-dimensional reversal, extra-dimensional shift, and extra-dimensional reversal62,83). In our sample, no variability in successful performance was found by iron status in infancy on the intra-dimensional shift stage. Although reduced levels of success were apparent on the extra-dimensional shift stage, differences were not found in relation to early iron status. Instead, marginal group differences were found at the final extra-dimensional reversal stage, such that young adults who had experienced chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy exhibited difficulty inhibiting the response that was previously rewarded at the extra-dimensional shift stage. This effect was found even though young adults who had good iron status in infancy made a greater number of errors on the stages preceding the intra-dimensional shift. Taken together, these findings indicate that individuals with good iron status in infancy made more errors during the early stages of the set-shifting task but were marginally more successful during the final stage of testing. Although unclear as to why the effects of chronic, severe iron deficiency only manifested themselves at the last stage of testing, the results nonetheless corroborate findings from the Trail Making Test, which indicated that chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy resulted in less success when shifting between task requirements and in inhibiting previously-relevant response sets.

In addition to the apparent deficits in inhibitory control and set-shifting, young adults who had chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy also exhibited difficulty forming and executing action plans. On the Stockings of Cambridge subtest of the CANTAB, young adults who had experienced chronic, severe iron deficiency had impaired planning abilities relative to participants with good early iron status, such that they spent less time considering their first move on the most challenging 5-move problems. The absence of group differences in the time to plan subsequent moves suggests that young adults with chronic, severe iron deficiency were at a clear planning disadvantage relative to participants with good iron status. The lack of planning by young adults who had chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy was evident in their behavioral performance, as they required more moves to solve the most difficult 5-move problems, relative to participants with good early iron status. Taken together, these data suggest that chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy resulted in planning deficits even 17-18 years after treatment, with concomitant negative outcomes in behavioral performance. However, the between-subjects effect for 5-move problems became non-significant after controlling for concurrent IQ. This mediating effect raises questions regarding the directionality and reciprocity of interactions between neurocognitive capabilities, particularly those concerning executive functions, and measures of general intelligence obtained at the same time.

Differences in performance were not apparent as a function of iron status in infancy on the Spatial Working Memory subtest of the CANTAB or on an independent Stimulus-Response Incompatibility task. We propose that the lack of significant group differences resulted from differential sensitivity of the chosen measures to subtle deficits in dopamine-mediated executive functions. For example, individuals with severe Parkinson’s disease exhibit impairment on the Spatial Working Memory subtest of the CANTAB relative to controls, whereas those who are less affected experience little difficulty.84 In another example, individuals given 400 mg of the dopamine D2 antagonist sulpiride exhibit impaired performance on a complicated spatial working memory-sequence generation task whereas those given a dose of 200 mg do not.34 However, administration of a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist to normal volunteers did not impact performance on the Spatial Working Memory subtest of the CANTAB,85 thereby suggesting that this task may not be sensitive enough to detect the effects of subtle deficits in dopamine-mediated executive functions. The same may be true of the measure of stimulus-response incompatibility. Because participants completed all of the compatible trials before the incompatible trials (and because completion of the incompatible trials was preceded by a short block of practice trials), the inhibitory control requirements of this task may have been minimized over the course of testing. Future research should address these concerns by including more sensitive measures of spatial working memory and stimulus-response incompatibility.

Measures of Medial Temporal Lobe-Dependent Recognition Memory

Participants with chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy also performed less well on the hippocampus-based Pattern Recognition Memory subtest of the CANTAB, especially at longer self-imposed response latencies. However, significant differences in response latency or accuracy by iron status group were not apparent on this subtest or for any variables on the Spatial Recognition Memory subtest, which also relies on the integrity of the medial temporal lobes.

One possible reason for the apparent lack of more obvious group effects on measures of medial temporal lobe functioning may be that only two CANTAB subtests of recognition memory were included. The inclusion of a larger number of hippocampus-based tests in future studies would provide greater opportunity to identify such effects, if present. Another possible reason for the relative lack of significant effects on measures of medial temporal lobe functioning may relate to the presumed timing of iron deficiency. Previous studies indicating iron-related deficits on hippocampus-mediated tests include samples of infants who had prenatal, rather than postnatal, iron deficiency22,37,41-43 likely resulting from gestational diabetes or intrauterine growth restriction (see review4). Indeed, a recent nonhuman primate model of purely prenatal versus purely postnatal iron deprivation showed different effects on cognitive, affective, and motor domains depending on timing.86-87 The participants in the present study had documented postnatal iron deficiency, but their prenatal iron status was unknown. If their iron deficiency was primarily postnatal, our results indicate that long-term outcomes may differ from those found in individuals who experienced solely prenatal iron deficiency. The extent to which the timing and a combination of prenatal and postnatal iron deficiency relates to cognitive, affective, and motor function in humans remains to be determined but is likely an important factor in understanding the varied results that may be obtained when iron deficiency occurs at different points in ontogeny.

Potential Mechanisms Underlying the Obtained Pattern of Results

The obtained pattern of results suggests that deficits in inhibitory control, set-shifting, planning, and recognition memory are among the long-term outcomes associated with chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy and may relate to the long-term global deficits seen in this sample.17 In this section, we propose that the observed neurocognitive impairments may relate to the effects of iron deficiency on the dopamine system, the hippocampus, and their interaction.

Research conducted with animal models of chronic, severe iron deficiency have indicated that elevations in extracellular dopamine resulting from the reduced number and/or functionality of dopamine receptors and transporters (leading to decreased dopamine activity) persist after treatment for nutrient insufficiency and have long-lasting functional implications.26,28,88 To date, there are no documented direct relations between early iron deficiency and dopamine concentrations and/or binding in humans. However, the patterns of results obtained in the affective and motor domains with rats21 and humans13,89-90 suggest that alterations in dopamine-dependent pathways may be responsible. This investigation provides evidence that these alterations may also result in long-term negative outcomes on measures of frontostriatal integrity in humans.

Indeed, the role of dopamine has been established as critical in the successful completion of frontostriatally-mediated executive functions83,91 and in hippocampus-based memory tasks in humans.92 There is also evidence of functional interactions between these two systems. For example, the binding of hippocampal D2 receptors affects performance on measures of hippocampal functioning, such as non-verbal and verbal delayed recall tests. In addition, measures of dopamine binding in the hippocampus also relate significantly to performance on the Wisconsin Card Sort,92 a classic measure of prefrontal function. The mesocortical dopamine system also critically modulates hippocampal-dependent long-term potentiation,93 thereby indicating that hippocampal and prefrontal neurons are connected at the level of the cell94 and the system,95 with evidence of functional integration as well.93,96

Although speculative, the apparent group differences on the Pattern Recognition Memory subtest of the CANTAB may be due, at least in part, to the functional connections between the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Successful performance on this task has documented relations with medial temporal lobe structures (e.g., lesions of the medial temporal lobe produce gross deficits in visual recognition memory70,97). However, lesions to nonhuman primate ventromedial prefrontal cortex also abolish successful recognition, which likely depends on the transmission of information from medial temporal lobe structures through the fornix and the thalamus.75 Although deficits in visual recognition memory have not been found in humans with frontal lobe damage,70 this null effect may be due to the location of the lesion and not to a lack of prefrontal involvement, as different regions of prefrontal cortex may be involved in dissociable aspects of visually-mediated cognition.71,97-98 Consequently, successful performance on the Pattern Recognition Memory subtest of the CANTAB may not be indicative of “pure” deficits in medial temporal lobe functioning. Future research, potentially using neuroimaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET83), may help chart relations between dopamine binding and performance on prefrontal-striatal tasks of executive function and hippocampus-dependent memory tasks in samples of participants who did and did not experience chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy.

Conclusions

In the present study, young adults who experienced chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy had had difficulty on tests requiring inhibitory control, set-shifting, planning, and recognition memory relative to participants with good early iron status. Although some of the effects were subtle and require confirmation through replication, previous investigations with this sample have indicated that affected participants were impaired on global measures of cognitive, affective, and motor functioning in infancy9-10,13 and at 5 years,15,90 cognition and affect at 10 years,16 and overall cognitive functioning up to 19 years.17 Effects obtained on the neurocognitive battery employed in the present assessment indicate that specific deficits persist almost 2 decades after the identification and treatment of early iron deficiency. The pattern of results is consistent with the altered function of frontostriatal circuits and the hippocampus and suggests that neurodevelopment during the first two years of life may set the stage for long-term executive functioning and recognition memory. Future research is needed to assess whether the effects of chronic, severe iron deficiency in infancy are specific to the examined brain regions or whether other neural circuits are also affected. Given that iron is involved in many processes in the brain, subtle and diffuse deficits are expected, although some brain areas and functions may be more affected than others. We were unable to examine this possibility in our study because the complexity and length of the test battery at 19 years precluded a comprehensive examination of many neural systems. Nevertheless, the persistence of negative outcomes on measures of executive function and recognition memory in this study and on other measures of long-term cognitive, affective, and motor performance in related research highlights the need for primary prevention to reduce the prevalence of iron deficiency and secondary prevention to lessen the long-term effects of this pervasive nutrient disorder.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, including a MERIT Award to Betsy Lozoff, M.D. (R01-HD31606 and R23-HD31606). We are grateful to the families who have maintained their commitment to participating in these studies for almost two decades and to Elias Jimenez, M.D., for his leadership on this project since its inception.

Footnotes

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Angela F. Lukowski, University of Michigan Center for Human Growth and Development 300 North Ingalls, 10th Floor Ann Arbor, MI 48104 Phone: 734-647-9569 Fax: 734-936-9288 aflukows@umich.edu

Marlene Koss, Hospital CIMA – San Jose Department of Psychology and Psychiatry Escazu, Costa Rica Phone: 506-208-1609 Fax: 506-208-1630 mkoss@hospitalcima.com

Matthew J. Burden, Wayne State University Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences 2751 East Jefferson, Suite 460 Detroit, MI 48207 Phone: 313-993-5454 Fax: 313-993-3427 mburden@wayne.edu

John Jonides, University of Michigan Department of Psychology 530 Church Street Ann Arbor, MI 48109 Phone: 734-764-0192 Fax: 734-764-3520 jjonides@umich.edu

Charles A. Nelson, Harvard University Departments of Pediatrics 1 Autumn Street Office AU621, Mailbox #713 Boston, MA 02115 Phone: 617-355-0401 Fax: 617-730-0518 canelson@childrens.harvard.edu

Niko Kaciroti, University of Michigan Center for Human Growth and Development 300 North Ingalls, 10th Floor Ann Arbor, MI 48104 Phone: 734-763-9714 Fax: 734-936-9288 nicola@umich.edu

Elias Jimenez, Hospital CIMA – San Jose Department of Psychology and Psychiatry Escazu, Costa Rica Phone: 506-208-1609 Fax: 506-208-1630 ejimenez@hospitalcima.com

Betsy Lozoff, University of Michigan Department of Pediatrics Center for Human Growth and Development 300 North Ingalls, 10th Floor Ann Arbor, MI 48104 Phone: 734-764-2443 Fax: 734-936-9288 blozoff@umich.edu

References

- 1.Stoltzfus RJ. Defining iron-deficiency anemia in public health terms: A time for reflection. J Nutr. 2001;131:565S–567S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.2.565S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prevention and Control of Iron Deficiency Anaemia in Women and Children. Geneva: 1999. Report of the UNICEF/WHO Regional Consultation. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brotanek JM, Halterman J, Auinger P, Flores G, Weitzman M. Iron deficiency, prolonged bottle-feeding, and racial/ethnic disparities in young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:1038–1042. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.11.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lozoff B, Georgieff MK. Iron deficiency and brain development. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2006;13:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akman M, Cebeci D, Okur V, Angin H, Abah O, Akman AC. The effects of iron deficiency on infants’ developmental test performance. Acta Paediatr. 2004;93:1391–1396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasanbegovic E, Sabanovic S. [Effects of iron therapy on motor and mental development of infants and small children suffering from iron deficiency anaemia]. [Bosnian] Medicinski Arhiv. 2004;58:227–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Idjradinata P, Pollitt E. Reversal of developmental delays in iron-deficient anaemic infants treated with iron. Lancet. 1993;341:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92477-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lozoff B, Brittenham GM, Viteri FE, Wolf AW, Urrutia JJ. Developmental deficits in iron deficient infants: Effects of age and severity of iron lack. J Pediatr. 1982;101:948–952. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(82)80016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lozoff B, Brittenham GM, Wolf AW, McClish DK, Kuhnert PM, Jimenez E, Jimenez R, Mora LA, Gomez I, Krauskopf D. Iron deficiency anemia and iron therapy: Effects on infant developmental test performance. Pediatrics. 1987;79:981–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walter T, De Andraca I, Chadud P, Perales CG. Iron deficiency anemia: Adverse effects on infant psychomotor development. Pediatrics. 1989;84:7–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walter T, Kovalskys J, Stekel A. Effect of mild iron deficiency on infant mental development scores. J Pediatr. 1983;102:519–522. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(83)80177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lozoff B, Klein NK, Nelson EC, McClish DK, Manuel M, Chacon ME. Behavior of infants with iron deficiency anemia. Child Dev. 1998;69:24–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lozoff B, Wolf AW, Jimenez E. Iron deficiency anemia and infant development: Effects of extended oral iron therapy. J Pediatr. 1996;129:382–389. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palti H, Meijer A, Adler B. Learning achievement and behavior at school of anemic and non-anemic infants. Early Hum Dev. 1985;10:217–223. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(85)90052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lozoff B, Jimenez E, Wolf AW. Long-term developmental outcome of infants with iron deficiency. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:687–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199109053251004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lozoff B, Jimenez E, Hagen J, Mollen E, Wolf AW. Poorer behavioral and developmental outcome more than 10 years after treatment for iron deficiency in infancy. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E51. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.4.e51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lozoff B, Jimenez E, Smith JB. Double burden of iron deficiency and low socio-economic status: A longitudinal analysis of cognitive test scores to 19 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:1108–1113. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.11.1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dallman PR. Biochemical basis for the manifestations of iron deficiency. Ann Rev Nutr. 1986;6:13–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.06.070186.000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beard JL, Felt B, Schallert T, Burhans M, Connor JR, Georgieff MK. Moderate iron deficiency in infancy: Biology and behavior in young rats. Behav Brain Res. 2006;170:224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erikson K, Pinero DJ, Connor JR, Beard JL. Regional brain iron, ferritin and transferrin concentrations during iron deficiency and iron repletion in developing rats. J Nutr. 1997;127:2030–2038. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.10.2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Felt BT, Beard JL, Schallert T, Shao J, Aldridge JW, Connor JR, Georgieff MK, Lozoff B. Persistent neurochemical and behavioral abnormalities in adulthood despite early iron supplementation for perinatal iron deficiency anemia in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2006;171:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rao R, Tkac I, Townsend EL, Gruetter R, Georgieff MK. Perinatal iron deficiency alters the neurochemical profile of the developing rat hippocampus. J Nutr. 2003;133:3215–3221. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.10.3215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beard JL, Connor JR. Iron status and neural functioning. Ann Rev Nutr. 2003;23:41–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.23.020102.075739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashkenazi R, Shachar D Ben, Youdim MB. Nutritional iron and dopamine binding sites in the rat brain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1982;17(Suppl 1):43–47. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beard JL, Chen Q, Connor J, Jones BC. Altered monamine metabolism in caudate-putamen of iron-deficient rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;48:621–624. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson C, Erikson K, Pinero DJ, Beard JL. In vivo dopamine metabolism is altered in iron-deficient anemic rats. J Nutr. 1997;127:2282–2288. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.12.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ben-Shachar D, Ashkenazi R, Youdim MBH. Long-term consequence of early iron-deficiency on dopaminergic neurotransmission in rats. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1986;4:81–88. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(86)90019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lozoff B, Beard J, Connor J, Felt B, Georgieff M, Schallert T. Long-lasting neural and behavioral effects of iron deficiency in infancy. Nutr Rev. 2006;64:S34–S43. doi: 10.1301/nr.2006.may.S34-S43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seamans JK, Yang CR. The principal features and mechanisms of dopamine modulation in the prefrontal cortex. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;74:1–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brozoski TJ, Brown RM, Rosvold HE, Goldman RS. Cognitive deficit caused by regional depletion of dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rhesus monkey. Science. 1979;205:929–932. doi: 10.1126/science.112679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawaguchi T, Goldman-Rakic PS. D1 dopamine receptors in prefrontal cortex: Involvement in working memory. Science. 1991;251:947–950. doi: 10.1126/science.1825731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sawaguchi T, Matsumura M, Kubota K. Effects of dopamine antagonists on neuronal activity related to a delayed response task in monkey prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1990;63:1401–1412. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.6.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mehta MA, Swainson R, Ogilvie AD, Sahakian J, Robbins TW. Improved short-term spatial memory but impaired reversal learning following the dopamine D2 agonist bromocriptine in human volunteers. Psychopharmacol. 2001;159:10–20. doi: 10.1007/s002130100851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehta MA, Sahakian BJ, McKenna PJ, Robbins TW. Systemic sulpiride in young adult volunteers simulates the profile of cognitive deficits in Parkinson’s disease. Psychopharmacol. 1999;146:162–174. doi: 10.1007/s002130051102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tost H, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Klein S, Schmitt A, Hohn F, Tenckhoff A, Ruf M, Ende G, Rietschel M, Henn FA, Braus DF. D2 antidopaminergic modulation of frontal lobe function in healthy human subjects. Biol Psychiatr. 2006;60:1196–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jorgenson LA, Wobken JD, Georgieff MK. Perinatal iron deficiency alters apical dendritic growth in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Dev Neurosci. 2003;25:412–420. doi: 10.1159/000075667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jorgenson L, Sun M, O’Connor M, Georgieff MK. Fetal iron deficiency disrupts the maturation of synaptic efficacy in area CA1 of the developing rat hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2005;15:1094–1102. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Felt BT, Lozoff B. Brain iron and behavior of rats are not normalized by treatment of iron deficiency anemia during early development. J Nutr. 1996;126:693–701. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.3.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McEcheron MD, Cheng AY, Liu H, Connor JR, Gilmartin MR. Perinatal nutritional iron deficiency permanently impairs hippocampus-dependent trace fear conditioning in rats. Nutr Neurosci. 2005;8:195–206. doi: 10.1080/10284150500162952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siddappa AM, Georgieff MK, Wewerka S, Worwa C, Nelson CA, deRegnier R-A. Iron deficiency alters auditory recognition memory in newborn infants of diabetic mothers. Ped Res. 2004;55:1034–1041. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000127021.38207.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]