Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE:

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is a common problem with severe short and long-term consequences to the abused child, the family and to society. The aim of this study was to evaluate the extent of CSA, and demographic and other characteristics of the abused and their families.

DESIGN AND SETTING:

Retrospective and descriptive study based on a review of medical records of CSA cases from 2000-2009 at Sulmaniya Medical Complex, the main secondary and tertiary medical care facility in Bahrain.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

The review included demographic data, child and family characteristics, manifestations and interventions.

RESULTS:

The 440 children diagnosed with CSA had a mean age of 8 years (range, 9 months to 17 years); 222 were males (50.5%) and 218 were females (49.5%). There was a steady increase in cases from 31 per year in 2000 to 77 cases in 2009. Children disclosed abuse in 26% of cases, while health sector professionals recognized 53% of the cases. Genital touching and fondling (62.5%) were the most common form of CSA, followed by sodomy in 39%. Gonorrhea was documented in 2% of the cases and pregnancy in 4% of the females. The illiteracy rate among the fathers and mothers was 9% and 12%, respectively, which is higher than the rate among the adult general population. Children came from all socio-economic classes. There was referral to police in 56%, public prosecution in 31% of the cases, but only 8% reached the court.

CONCLUSION:

During ten years there has been a 2.5% increase in reported cases of CSA. Improving the skill of professionals in identifying CSA indicators and a mandatory reporting law might be needed to improve the rate of recognition and referral of CSA cases. Further general population-based surveys are needed to determine more accurately the scope of CSA and the risk and protective factors in the family and community.

Child abuse and neglect is a common problem in pediatrics and a major public health concern world-wide.1 Child sexual abuse (CSA) is one of the most traumatic forms of maltreatment of children with well documented devastating short- and long-term health consequences manifesting as physical and mental disorders. The association between child abuse and neglect and the leading causes of death are well illustrated in several studies worldwide. In the US, the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study showed a strong link between child abuse and neglect and chronic diseases such as obesity, heart disease, diabetes, hypertension and cancer.2 Furthermore, several other recent studies from the UK and US documented a highly significant association between CSA and many psychiatric disorders such as anxiety disorders, depression, eating disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sleep disorders, and suicidal attempts.3–5 Research about child abuse in general and CSA specifically is very scarce in the Arab region. The available research shows that child abuse and neglect are common and underreported. CSA is even more underestimated than child abuse and neglect in general. Several case reports about child abuse and neglect Saudi Arabia in the 1990s reported six (15%) cases of CSA out of forty cases of child abuse and neglect.6 A more recent retrospective study of suspected child abuse and neglect cases evaluated at King Abdulaziz Medical City in Riyadh from 2000 to 2008 revealed 20 (11%) cases of CSA out of 188 child abuse and neglect cases.7

In another study from Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 78 cases of CSA were recognized in a pediatric surgery unit from 1987 to 2007.8 Dysfunctional elimination syndrome (DES) was the main symptom in 11/78 (14%) of the abused children. Another study based on a cross-sectional survey was conducted among 419 adolescent females in two schools in Riyadh city and 10% of the girls reported exposure to sexual violence.9 Considering the conservative nature of the society and the dire social and legal ramifications of CSA, such revelations are courageous.

A study from Bahrain in 2001, documented CSA in 97 children with 74% of the boys and 8% of the girls subjected to sodomy.10 Vaginal penetration reported in 36% of the girls and pregnancy in 12%. Similarly, research about CSA from other Arab regions is also very limited. An epidemiological study from Morocco, conducted among a representative sample of the female population, aged 20 years, revealed CSA in 9.2% (n=65) of the 728 interviewed women. Genital contact with penetration was reported by 33.8% (22 cases). Abused women had significantly more depressive symptoms than non-abused women (43.5% and 29.5% respectively with a P value of .03).11 A more recent report from Morocco reported 306 cases of CSA in 2008.12

A study of 100 Jordanian male college students 18 to 20 years of age revealed CSA in 27% that had occurred before 14 years of age. In addition, those who experienced CSA had more mental health problems than those who did not.13 A recent population-based survey of 1028 (54% boys; 46% girls) Lebanese children documented CSA in 249 (24%). Furthermore, victimized girls had more psychological problems such as sleep disturbance, somatization, PTSD and anxiety than did victimized boys.14 Another study from Turkey evaluated 101 cases of CSA. Anal or vaginal penetration was reported in 48.5% of the cases. PTSD was the most common (54.5%) psychiatric diagnosis among the victims.15

This wide variation in the number and the rate of CSA reported in different studies is most likely related to the variation in methodologies and differences in definitions of CSA, data collection tools, the phrases used in the questionnaires, study populations and sampling techniques. Nonetheless, the limited research about child abuse and neglect in the region does not imply limited incidence of child maltreatment. A UN study about violence against children indicated that all forms of child abuse and neglect exist in every corner of the world.16 The UN study findings put the issue of prevention and treatment of child abuse and neglect in the center of the world community agenda with emphasis on the urgency of implementation of the study recommendations. This requires the concerted efforts of all countries to identify the magnitude of the problem and address the consequences of child abuse and neglect effectively using evidence-based preventive and therapeutic measures.17

The significance of CSA stems from the fact that it is a common problem with severe short- and long-term consequences to the abused child, the family and to society. It requires intensive resources from the medical, mental health and social services and coordination with the law-enforcement and court system. Studying CSA status in Bahrain will fill the gap in our knowledge about the problem and will help in guiding the planning for prevention and addressing the multidisciplinary services needed by the abused children and their families. The aim of this study was to evaluate the extent of CSA, demographic conditions, and the characteristics of the abused and their families.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Sulmaniya Medical Complex (SMC) is a secondary and tertiary care general hospital with about 1000 beds, of which 135 are pediatric beds. The Child Protection Unit (CPU) at SMC is run by a multidisciplinary team providing full assessment and treatment for all cases of child abuse and neglect referred to SMC. The team includes pediatricians, child psychiatrists, social workers and nurses.

According to the Central Informatics Organization, the average population in Bahrain is about 780 749 for the years 2000-2008.18 About 20% of the population is under 15 years of age. The unemployment rate in Bahrain is estimated to be 3.6%19 and the adult illiteracy rate for the year 2009 is estimated to be 2.5%.20 The overall infant mortality rate in Bahrain is 7.5 per 1000 live births in 2008. More than 96% of infants are immunized for DPT, polio, hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenza b, and 99.9% for measles-mumps-rubella. Almost all women (99.4%) deliver their babies under trained personnel supervision.21

The study was descriptive and based on a retrospective review of the CPU medical records of child sexual abuse cases evaluated over the last ten years, from 2000-2009. It included all children from birth to younger than 18 years of age who were evaluated by the CPU for sexual abuse. Cases that had signs and symptoms indicative of diseases mimicking child sexual abuse were excluded. The key elements included were the demographic data, family, child characteristics, genital findings and interventions. The nature of father's job was used as a general measure of socioeconomic status. Highly-paid jobs were managers and professionals such as doctors, engineers and lawyers. Moderately-paid jobs were like those for teachers and supervisors. Low-paid jobs were such as laborers and all other blue collar jobs.

The operational definition of CSA adopted in this study is “the engaging of a child in sexual activities that the child cannot comprehend and for which the child is developmentally unprepared and cannot give consent. It ranges from exhibitionism and fondling to intercourse (vaginal and anal). It includes voyeurism, exhibitionism and the use of children in the production of pornography and through the Internet”. Data collection consisted of reviewing all patient files and recording the required data and coding it carefully by the two investigators. SPSS version 17 for Windows was used for data management and analysis. Two data entry specialists entered the coded data, who checked it for accuracy and errors of coding. The authors also checked the data independently. The data were inspected carefully and a frequency distribution was done for all variables and any odd codes or items were double checked and corrected or deleted accordingly.

This study was based on a review of medical records; the identity of the patients was kept strictly confidential. Institutional scientific and ethical clearance for this research proposal was obtained from the Health Research Committee at SMC. This study was not funded by any funding agency and there was no conflict of interest declared by the authors. The results of this study nay have implications to population health and health system policy in Bahrain. The results are expected to potentially contribute to decision making related to health care, social policy and legal reforms related to child protection in Bahrain.

RESULTS

The number of children diagnosed exposed to CSA was 440. The mean age was 8 years and ages ranged from 9 months to 17 years; 222 (50.5%) were males and 218 (49.5%) were females. Sixty-eight were preschool children (15.5%), 75 in kindergarten (17%), 266 in primary school (60.5%), 9 in intermediate school (2%), and 7 in secondary school and special education (2%) each. Eight were drop outs or had unknown school status. Bahraini children constituted 404 (92%) and non-Bahrainis 36 (8%). CSA was certain in 391 (89%), very suspicious in 33 (7%) and suspicious in 16 (4%) of the cases. Unsubstantiated cases were not included and their details were unknown because they are not included in the child abuse register. Despite some of the variations from one year to another, over the last ten years there has been a clear trend of increase in the number of cases from 31 per year in 2000 to 77 in 2009. CSA occurred in all areas of Bahrain; however, in order of frequency, Manama, Muharraq, the Northern area and Sitra had more cases than other regions and this corresponds with the higher population density in these areas.22

Most of the CSA cases were referred from other SMC departments (136 cases; 31%), followed by local health centers in 88 (20%), and the Bahrain Center for Child Protection (BCCP) in 75 (17%). Police referred 63 (14%) and public prosecutors referred 5 (1%) of the cases. Schools referred 9 cases (2%) and private clinics and hospitals referred 8 cases (2%). The main location where abuse occurred was in the family or the homes of relatives in 235 cases (53%), Public places or deserted houses in 81 cases (18%), schools in 25 cases (6%), neighbors’ homes in 32 cases (7%), shops in 26 cases (6%), in mosques in 7 cases (2%), abuser homes in 4 (1%) and unknown places in 29 cases (7%).

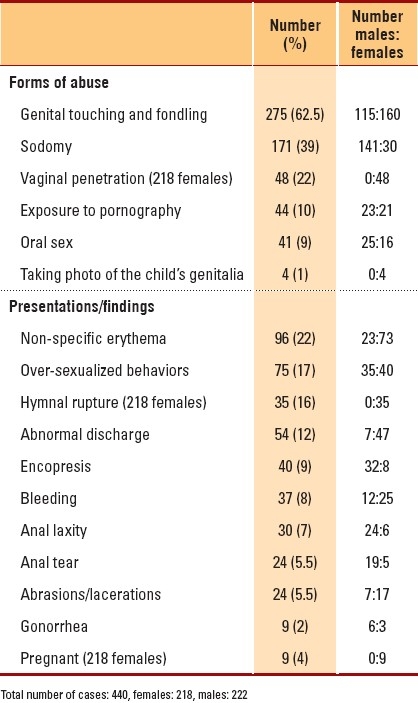

As shown in the Table 1 genital touching and fondling is the most common form of sexual abuse, which was committed against 275 (62.5%) of the children, followed by sodomy in 171 (39%) and vaginal penetration in 22% of the females. In sodomy, boys were the main victims in 141 (82.5%) and females in 30 (17.5%) of the cases. Ten percent of the children were exposed to pornography and 9% were subjected to oral genital contact. Over-sexualized behaviors (17%) were the most common presentation. In 134 (31%) children abuse occurred once only, twice or three times in 38 (9%), more than 3 times in 179 (41%), and an unknown number of times in 89 (20%) of the cases. Children disclosed abuse in 113 (26%) of the cases.

Table 1.

Forms and presentations of child sexual abuse.

Investigation for sexually transmitted diseases is done routinely for all children. No warts, hepatitis C or B or HIV cases were documented. However, gonorrhea was diagnosed in 9 (2%) of the total cases with female to male ratio is 2 to 1. Pregnancy was documented in 9 girls (4%) with an age range from 11-17 years.

The parents of 82 (19%) children were divorced. The unemployment rate among the fathers was 23 (5%). Low socio-economic status was documented in 208 (47%) of the study population. However, 22 (5%) of the fathers were from a high socio-economic class and 148 (34%) were from a moderate socio-economic class. Thirty-nine (9%) of the fathers and 53 (12%) of the mothers were illiterate.

The child lived with both parents in 319 (72.5%) of the cases, with the mother in 74 (17%), with the father in 22 (5%), with relatives and others in 8 (2%) and who the child lived with was unknown in 17 (4%). In 346 (79%) of the cases the father was married to one wife, in 34 (8%) of the cases the father was married to 2 to 3 wives, and 19 (4%) were single. The rate among the general population was unknown for comparison. Alcohol abuse was reported among 58 (13%) of the fathers and 9 (2%) of the mothers, while drug abuse was reported in 19 (4%) of the fathers and 6 (1%) of the mothers. A criminal record was reported among 44 (10%) of the fathers and 9 (2%) of the mothers. Similarly, the rate among the general population is unknown.

Children received medical care in 417 cases (95%) and surgical care in 7 cases (2%). Additionally, 339 (77%) and 360 (82%) had psychiatric referral and social intervention respectively. There was referral to police in 247 (56%) and public prosecution in 135 (31%) of the cases, but only 36 (8%) cases reached the court. Twenty children (4.5%) were removed from the abusive environment by granting custody to a non-abusive parent or to a grandmother by a public prosecutor or a court order. In eight cases children were taken into state custody.

DISCUSSION

This study of 440 children is the largest case series on reported CSA in Bahrain. Although SMC is the main general hospital with the largest pediatrics wards and the only child protection unit on the island, the number of cases by no mean represents the real size of the problem. Undoubtedly, there are many cases seen in other medical settings and not referred to SMC. In addition, SMC is a tertiary care medical facility and severe cases are mainly referred there so these cases most likely represent only the tip of the iceberg.

In this study, despite the variation in the number of CSA cases from year to year, the trend shows an increase in cases from 31 per year in 2000 to 77 cases in 2009. It is not clear if this rise in the number of cases is due to a genuine increase in the incidence of CSA cases or due to increased public and professional awareness and improved recognition and referral. It is most likely due to more than one factor. A similar increasing trend in the number of cases of child abuse and neglect is documented in other countries. A recent report from Morocco revealed a six-times increase in reported CSA in 2008 in comparison with 2007.12 The Moroccan study did not identify the exact cause(s) for such marked increase in the number of reported cases in one year.

Similarly, three US national incidence studies of child abuse and neglect in 1979, 1986 and 1993 (NIS-1, 2, 3) showed a relentless rise in the incidence of all forms of child maltreatment, but the fourth (2005) national incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS–4) showed a decline for the first time.23 Between the third and fourth NIS, the estimated number of children who experienced endangerment standard sexual abuse decreased by 40% in number and a 47% decline in rate.23

Another more recent study from the US has verified these trends of decline in several types of child victimization that were reported significantly less often in 2008 than in 2003; this included physical assaults, sexual assaults, and peer and sibling victimizations, including physical bullying.24 It appears that since the 1990s the reported rates of physical and sexual abuse are declining in the United States and England. The reason for this trend is not well understood.25

In this study children disclosed abuse in 26% of the cases only. Considering the culture of secrecy and the dynamics of children disclosure, this low rate of disclosure is not surprising. Well established research across cultures documented that most victims of CSA never disclose abuse or recant.26,27 Even after disclosure, CSA victims are known to be unwilling to report the abuse, especially in police interviews. In a study from Sweden, children's self-reports of the abuse were compared to videotapes of the incidents made by the lone perpetrator. The study documented a significant tendency among the children to deny or belittle their experiences.28 In a more recent study of CSA, from Sweden as well, children reported to police significantly more neutral information from the abusive acts per se than sexual information. The children were also highly avoidant and, on several occasions, denied that (documented) sexual acts had occurred.29

Another recent and more extensive review of current evidence from two main sources: retrospective accounts from adults reporting CSA experiences and studies of children undergoing forensic evaluation for CSA, supported the notion that children often delay abuse disclosure.30 It is well recognized that disclosure is determined by a complex interplay of factors related to child characteristics, family environment, community influences, and cultural and societal attitudes.31 Therefore, children's low disclosure is not surprising and this study is most likely to have uncovered the “tip of the iceberg” only and that most victims suffer behind closed doors and go unrecognized, and are never investigated or treated. Identifying the hurdles to disclosure and underrecognition and referral by professionals is essential in the quest to combat CSA.

Male and female victims are almost equal in number (50.5% and 49.5%, respectively). A similar observation was made in a previous study in 2001 in Bahrain where males represented 55% of the victims of CSA.10 Age is a well known risk factor and is related differently to various types of abuse. In this study, primary school children (ages 6-12 years) are the main victims of CSA (60.5%). Preschoolers (less than 3 years old) and kindergarten (4-5 years old) were also subjected to CSA in 15% and 17% of cases, respectively. The number of younger children is most likely to be even higher than this, because in preverbal children the event is unlikely to be disclosed by the child or witnessed by another person. In addition, there is a high likelihood of the event slipping from the child's memory. This is well documented by sound research which has revealed 17 years following the initial report of the abuse. Eighty of 129 (62%) women recalled the victimization.32

In this study, health sector professionals recognized and referred 53% of the total cases. The referrals from public medical services were 51% and from private clinics and hospitals 2%, thus the ratio of referrals is 25:1. This does not reflect the difference in patient load between the public and the private health sectors. Central Informatics Organization records indicate that attendance at government hospitals and health units versus attendance at private hospitals is about 5:1 (4 391 000 vs. 833 000).18

Schools also recognized and referred only 2% of CSA cases, which contrasts sharply with the fact that schools have contact with over 71% of this study sample victims who were in kindergarten and above. This most likely reflects a failure in recognizing victims and /or unwillingness by school staff and teachers to refer victims of CSA. Both possibilities are worrisome and mandate attention of the concerned school authorities and calls for a mandatory reporting law. Educational institution response to cases of child abuse and neglect has been a subject of several research reports. An Australian study looked at the influence in multiple cases of teacher and school characteristics on 254 primary school teachers’ propensity to detect and report CAN. Case characteristics (type, frequency and severity of abuse) were found to exert the strongest influence on detecting and reporting tendency. At the teacher level, mandatory reporting obligations were found to be the strongest and most significant predictor of reporting.33 Another study of 480 teachers from Ohio in the US found that teachers use professional discretion in making judgments about the recognition and reporting of child abuse and that their use of discretion is more likely to result in underreporting than overreporting.34 Therefore, based on this study and our research data, it seems that improving teacher skills in identifying CSA indicators and mandatory reporting are important steps in improving the rate of recognition and referral of CSA cases.

BCCP was established in May 2007 (equivalent to 1.5 years of this study period). However, BCCP recognized and referred 17% of the study children. This is a testimony of the positive role played by BCCP in recognizing and responding to child abuse and neglect victims in Bahrain. As is well documented in many other studies, most of the events of CSA (68%) were committed in familiar places which are supposed to be a safe refuge for children such as family homes, schools, and mosques.

Like many other studies, genital touching and fondling (62.5%) was the most common form of CSA and followed by sodomy in 39% of the children. Similarly, the Canadian incidence study revealed that touching and fondling of the genitals was the most common form of substantiated sexual abuse (68%).35 Using standard culture techniques, gonorrhea was documented in 9 (2%) of the total cases. Despite some of the debate about the modes of transmission of genital gonorrhoea, so far no case of non-sexual transmission could be determined.36 Despite the fact that 22% of females disclosed vaginal penetration, only 16% showed abnormal hymenal findings. This is well documented in several studies which showed that genital injuries generally heal rapidly and most heal without residua and that except for deep lacerations and hymenal injuries, there is no scarring or evidence of trauma in most children.37 Another recent systematic review of published reports on genital findings in prepubertal girls with and without a history of sexual abuse indicated that posterior hymenal perforations, transections, and deep notches are consistent with sexual contact and essentially are never seen in non-abused girls.38

The divorce rate among 19% of the children's parents is slightly higher than the rate among the general population of Bahrain, which is estimated to be 15%.16 The unemployment rate among the fathers of abused children of 5% is higher than the official estimate of unemployment rate among the general population of 3.6% with females representing 75% and males 25% of the unemployed.19 In addition, low socio-economic status is overrepresented among families in this study (47%). Nonetheless 5% and 34% of the parents are of high and moderate socio-economic status, respectively. These observations reflect that although lower socio-economic status might put children at higher risk of CSA, higher socio-economic status does not guarantee the child's safety. The rate of illiteracy among fathers and mothers was much higher than the rate of adult illiteracy rate among the adult general population of Bahrain.20 All children received medical care (95%), surgical treatment (2%), psychiatric referral (77%) and social intervention (82%) as needed. In part, this is due to the fact that health care facilities are accessible to 100% of the population. Although referral to police occurred in 56% of cases and public prosecution in 31% of the cases only 8% reached the court and the outcome of those cases is unknown.

In general, health professionals are the main source of CSA case recognition and referral. Although child abuse and neglect has been recognized by novelists and writers from the time of antiquity, the first full scientific reports about child abuse and neglect were documented and published by physicians in medical literature more than 200 years ago.39,40 In addition, health professionals and services are more easily accessible by the general public than other disciplines. The main limitation of this study is that it is based on reported cases of child abuse and neglect to health services. This will invariably lead to underestimation of the size of the problem in and overestimate the severity of cases in the community.

In conclusion, this study is the largest case series about reported CSA in Bahrain and it revealed a steady increase in the number of cases. Children disclosed abuse in 26% of cases and this study is most likely to have only uncovered the “tip of the iceberg”. Although, most children came from a lower socio-economic class, a higher socio-economic status does not guarantee the child's safety. The parental illiteracy rate is higher than the general population. Children in the age range of 6-12 years are the main victims (60.5%). The main source of CSA recognition and referral is the health sector (53%) and the lowest referrals are from schools (2%). Improving the skills of professionals in identifying CSA indicators and a mandatory reporting law might be needed to improve the rate of recognition and referral of CSA cases. Further, general population-based surveys are needed to determine more accurately the scope of CSA and risk and protective factors in the family and community.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–58. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jonas S, Bebbington P, McManus S, Meltzer H, Jenkins R, Kuipers E, et al. Sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in England: Results from the 2007 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Psychol Med. 2011;41:709–19. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000111X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen LP, Murad MH, Paras ML, Colbenson KM, Sattler AL, Goranson EN, et al. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:618–29. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark C, Caldwell T, Power C, Stansfeld SA. Does the influence of childhood adversity on psychopathology persist across the lifecourse? A 45-year prospective epidemiologic study. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:385–94. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Mahroos FT. Child abuse and neglect in the Arab Peninsula. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:241–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al Eissa M, Almuneef M. Child abuse and neglect in Saudi Arabia: Journey of recognition to implementation of national prevention strategies. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raboei EH. Surgical aspects of child sexual abuse. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2009;19:10–3. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1038763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Quaiz AJ, Raheel HM. Correlates of sexual violence among adolescent females in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:829–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Mahroos F, Abdulla F, Kamal S, Al-Ansari A. Child abuse: Bahrain's experience. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29:187–93. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alami KM, Kadri N. Moroccan women with a history of child sexual abuse and its long-term repercussions: A population-based epidemiological study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7:237–42. doi: 10.1007/s00737-004-0061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.“Touche Pas à Mon Enfant”. Child Sexual Abuse on the rise in Morocco. 2009. [Last accessed on 2010 Sep 11]. Available from: http://cabalamuse.wordpress.com/2009/05/21/child-sexual-abuse-on-the-rise-in-morocco/

- 13.Jumaian A. Prevalence and long-term impact of child sexual abuse among a sample of male college students in Jordan. East Mediterr Health J. 2001;7:435–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Usta J, Farver J. Child sexual abuse in Lebanon during war and peace. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36:361–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bahali K, Akçan R, Tahiroglu AY, Avci A. Child sexual abuse: Seven years in practice. J Forensic Sci. 2010;55:633–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2010.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinheiro PS. World Report on Violence against Children. United Nations Secretary-General's Study on Violence against Children UN Geneva. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newton AW, Vandeven AM. Child abuse and neglect: a worldwide concern. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:226–33. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283377931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Central Informatics Organization. Bahrain in figures 2007-2008. 2010. [Last Accessed on 2010 Aug 12]. available from: http://www.cio.gov.bh/cio_ara/English/Publications/Bahrain%20in%20Figure/BIF2007_2008.pdf .

- 19.Women Gateway website. [Last accessed on 2010 Oct 12]. Available from: http://www.womengateway.com/arwg/MoneyBusiness/business+Report.htm .

- 20.Ministry of Education, Bahrain. [Last accessed on 2010 Oct 12]. web site: Available from: http://www.moe.gov.bh/MinistrySearchResultsPage.aspx .

- 21.Health Information Directorate, Health Statistics, Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Bahrain. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Central Informatics Organization. Bahrain National Census 2001. Kingdom of Bahrain. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Petta I, McPherson K, Greene A, et al. Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4): Report to Congress. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R, Hamby SL. Trends in childhood violence and abuse exposure: Evidence from 2 national surveys. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:238–42. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. 2009;373:68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Summit R. The child sexual abuse accommodation syndrome. Child Abuse Negl. 1982;7:177–93. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(83)90070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorenson T, Snow B. How children tell: The process of disclosure in child sexual abuse. Child welfare. 1991;70:3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sjöberg RL, Lindblad F. Limited disclosure of sexual abuse in children whose experiences were documented by videotape. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:312–4. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leander L. Police interviews with child sexual abuse victims: Patterns of reporting, avoidance and denial. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34:192–205. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.London K, Bruck M, Wright DB, Ceci SJ. Review of the contemporary literature on how children report sexual abuse to others: Findings, methodological issues, and implications for forensic interviewers. Memory. 2008;16:29–47. doi: 10.1080/09658210701725732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alaggia R. An ecological analysis of child sexual abuse disclosure: Considerations for child and adolescent mental health. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19:32–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams LM. Recovered memories of abuse in women with documented child sexual victimization histories. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8:649–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02102893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walsh K, Bridgstock R, Farrell A, Rassafiani M, Schweitzer R. Case, teacher and school characteristics influencing teachers’ detection and reporting of child physical abuse and neglect: results from an Australian survey.The entity from which ERIC acquires the content, including journal, organization, and conference names, or by means of online submission from the author. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32:983–93. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Webster SW, O’Toole R, O’Toole AW, Lucal B. Overreporting and underreporting of child abuse: teachers’ use of professional discretion. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29:1281–96. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Public Health Agency of Canada. At a glance: The Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect. Highlights. 2001. [Last accessed on 2010 Sept 3]. Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cm-vee/cishl01/index-eng.php .

- 36.Whaitiri S, Kelly P. Genital gonorrhoea in children: Determining the source and mode of infection. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:247–51. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.162909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pillai M. Genital findings in prepubertal girls: What can be concluded from an examination? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2008;21:177–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berkoff MC, Zolotor AJ, Makoroff KL, Thackeray JD, Shapiro RA, Runyan DK. Has this prepubertal girl been sexually abused? J Am Med Assoc. 2008;300:2779–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams AN, Griffin NK. 100 years of lost opportunity. Missed descriptions of child abuse in the 19th century and beyond. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32:920–4. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krafft-Ebing V. Psychopathia Sexualis. Internet Archive. 1922. [Last accessed on 2010 Oct 16]. pp. 552–560. Available from: http://www.archive.org/stream/psychopathiasexu00krafuoft#page/552/mode/2up .