Abstract

Background:

Family violence (FV) is a common, yet often invisible, cause of violence. To date, most literature on risk factors for family, interpersonal and sexual violence is from high-income countries and might not apply to Mozambique.

Aims:

To determine the individual risk factors for FV in a cohort of patients seeking care for injuries at three health centers in Maputo, Mozambique.

Setting and Design:

A prospective multi-center study of patients presenting to the emergency department for injuries from violence inflicted by a direct family member in Maputo, Mozambique, was carried out.

Materials and Methods:

Patients who agreed to participate and signed the informed consent were verbally administered a pilot-tested blank-item questionnaire to ascertain demographic information, perpetrator of the violence, historical information regarding prior abuse, and information on who accompanied the victim and where they received their initial evaluation. De-identified data were entered into SPSS 13.0 (SPSS, version 13.0) and analyzed for frequencies.

Results:

During the 8-week study period, 1206 assault victims presented for care, of whom 216 disclosed the relationship of the assailant, including 92 being victims of FV (42.6%). The majority of FV victims were women (63.0%) of age group 15-34 years (76.1%) and were less educated (84%) compared to national averages. Of the patients who reported assault on a single occasion, most were single (58.8%), while patients with multiple assaults were mostly married (63.2%). Most commonly, the spouse was the aggressor (50%) and a relative accompanied the victim seeking care (54.3%). Women most commonly sought police intervention prior to care (63.2%) in comparison to men (35.3%).

Conclusion:

In Mozambique, FV affects all ages, sexes and cultures, but victims seeking care for FV were more commonly women who were less educated and poorer.

Keywords: Emergency care, family violence, injuries, Mozambique

INTRODUCTION

Annually, more than 1.6 million people worldwide lose their lives due to self-inflicted, interpersonal or collective violence, with 90% of these deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries.[1] The financial cost of violence worldwide translates into billions of US dollars in healthcare expenditures and billions more in the economic impact from lost workdays and law enforcement.[1] Violence can be divided into self-directed, collective and interpersonal violence that is made up of family and intimate partner or community violence.[1] Family violence (FV) is a common manifestation of violence and is a universal problem affecting people of all socioeconomic backgrounds, educational levels, and gender.[2,3] Many victims perceive their abuse as a cultural or religious norm that is reinforced by prejudice and discrimination.[4]

FV, inclusive of intimate partner violence (IPV), child maltreatment and elder abuse, as defined by this study, is any act or conduct that causes death, injury or physical, sexual or psychological suffering between members of a given household or community united by family ties.[5] Surveys have shown that between 10 and 70% of women have suffered physical violence and 6-59% have suffered sexual violence by a partner.[6–8] Victims who suffer IPV are at risk for sexual assault and unwanted pregnancy or sexually transmitted diseases including HIV infection.[9] A study in India found that upwards of 26% of women suffered from abuse from their in-laws during the perinatal period, and those who suffered from physical and non-physical IPV by their husbands were significantly more likely to also suffer from abuse by their in-laws.[10]

FV impacts the victims as well as the victims’ families including children and adolescents, the community at large and society as a whole. One-quarter of working days lost for women in Latin America are related to IPV.[11] In developing countries, FV causes a reduction of 5-16% of healthy years for women of reproductive age.[5] IPV and sexual violence can lead to a wide array of long-term physical, mental and sexual health problems.[8,12]

In the last decade, awareness of FV has grown substantially. Law enforcement agencies, healthcare systems and government authorities in Mozambique have finally listed domestic violence as a priority and are more eager to support sustainable efforts to reduce its frequency.

A leading cause of utilization of emergency services in Mozambique is FV.[13] Emergency Departments (EDs) of health centers serve victims who seek care and act as a “gateway” to the spectrum of health-related services. It is crucial to be able to determine the risk and protective factors in order to prevent domestic and sexual violence.[14] An ecological model can organize the risk factors to the individual, relationships, community and societal levels in order to understand the complex interplay of all these factors for prevention and intervention.[9,15] Up to this point, most of the literature on risk factors for interpersonal, domestic and sexual violence has come from high-income countries.[1] The objective of this project was to determine the risk factors for FV victims who present for care in the capital city of a low-income country, Mozambique.

Mozambique is a coastal country on the southeastern portion of Africa, inhabited by over 22 million people, of whom 37% live in urban areas. Maputo, the capital, is located in Maputo province with approximately 2 million inhabitants.[16] Portuguese is the national language but is only spoken by just over a quarter of the population; there are about 70 dialects of tribal languages spoken, mostly of Bantu origin.[16] Mozambique has a young population with 44.8% under the age of 15, and average life expectancy is between 41 and 47 years.[17–19] The infant mortality rate is the 6th worst in the world at 104 per 1000 live births.[16]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was an observational cross-sectional study performed by convenience sampling of patients who sought medical treatment after self-reporting an assault by a family member, performed during the months of August and September 2007, at three health centers in Mozambique. Data were collected at the three hospital emergency departments 24 hours a day, 7 days a week during the study period. This study was approved by both an international Institutional Review Board and local Ethics Review Panel prior to data collection.

Preparation

The principal investigator (PI) selected interviewers from amongst nurses and health workers at each of the three study sites. Each potential interviewer received 4 hours of background training and an introduction to the survey questionnaire. Under the supervision of the PI, interviewers performed pilot testing of the instrument at a separate healthcare facility. Of the trained researchers, final interviewers were chosen based on work location and internal validity from the trial interviews.

Instrument

The two-page survey questionnaire was developed by the PI for the participants to answer the study questions. This questionnaire comprised multiple choice and yes/no format questions. Demographic information gathered included age, sex, level of schooling, religion and occupation. Further information regarding who caused the trauma, who presented with the victim to the health center, and where the victim first presented for care/treatment was collected.

Procedure

Currently, there is no standard protocol or practice for questioning patients about violence or safety. If a patient self-disclosed violence as a cause of his/her injury to the triage nurse, research personnel, who were not part of the treatment team, approached the victim after medical stabilization to offer participation. Potential subjects were approached by research personnel regardless of age, sex, or type of injury. The researcher informed the patient of the study protocol and risks and benefits and each patient signed an informed consent (or assent and guardian consent if the patient was under 18 years of age). Participants were able to withdraw from the study at any time and were not given any compensation for their participation. In a quiet, secluded, and safe location, the questionnaire was verbally administered to patients once they volunteered participation. Data were entered into SPSS (SPSS, version 13.0) and analyzed for frequencies and percentages. All data were free of identifiable information and were kept in a secure location to ensure patient confidentiality.

RESULTS

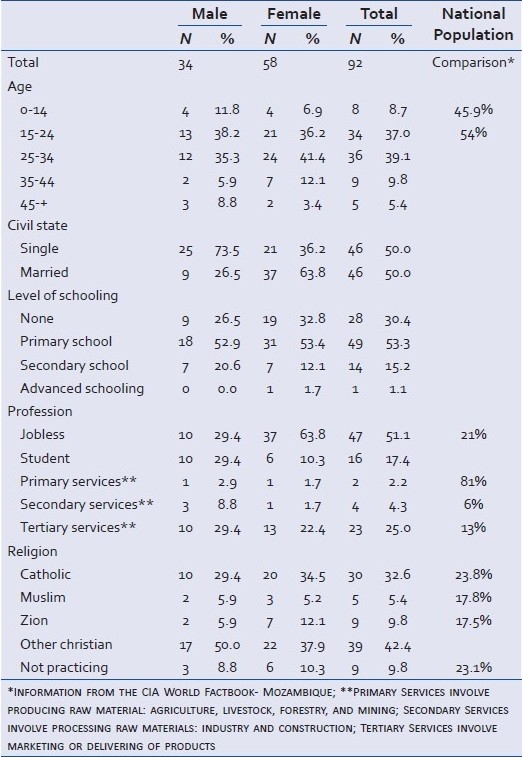

During the study time period, 1206 individuals presented for treatment of assault at the study facilities. Of these, only 216 disclosed the perpetrator of the violence. Of these 216, 92 (42.6%) were injured by members of the same household and were included in the data analysis, while 124 (57%) were injured by persons outside the family unit. Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of participants. Most participants were between 15 and 34 years of age (76.1%), had primary school or less education (83.7%), were students or had no formal career (68.5%) or were of Catholic or Christian religion (75.0%). Women had a mean age of 26.1 years and most were married (63.8%), while males had a mean age of 25.8 years and most were single (73.5%).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of victims of domestic violence

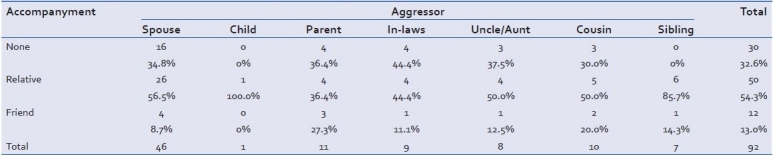

About 55% of victims were abused once, 21% twice and 24% three or more times in the last year. Patients abused only once in the past were mostly single (59%), while those abused twice or three or more times were more likely married (63%, 59%). Spouses were the most common aggressor (50%). In spousal assault, family accompanied the victim to the health unit 54% of the time [Table 2] and a friend accompanied the victim if the parent was the aggressor (27.3%). Females initially presented to the police and subsequently to the hospital in 62.1% of cases, while males primarily sought care at the hospital.

Table 2.

The aggressor and who accompanied the patient for care

DISCUSSION

This study is, to our knowledge, the first to examine the characteristics of victims of FV in Maputo, Mozambique. The data identify several important risk factors for FV victims seeking care in Maputo, including: age between 15 and 34 years, lower education level and lower income level. The world health organization (WHO) has reported that individual risk factors for IPV and sexual violence include young age, low education, antisocial personality disorder or depression, substance use and abuse and the acceptance of violence.[9] While most of the studies which provide this information have been conducted in high-income countries, our study from a low-income country supports some of these findings as well.

Our data are quite similar to WHO reports that globally, victims of domestic violence are mostly females aged between 15 and 44 years.[20] Most patients who presented for care at a health center in Maputo were less than 34 years of age (84.8%), yet very few patients were less than 15 years of age (8.7%). Young age is a risk factor for a man to commit physical violence against a partner and for a woman to experience IPV.[21–24] Younger women are more at risk of rape than older women.[12] According to the data collected from justice and rape crisis centers in Chile, Malaysia, Mexico, Papua New Guinea, Peru and the United States, between one-third and two-thirds of victims of sexual assault are 15 years or under.[9] Given that the life expectancy in Mozambique is 41 years (2010 estimate) and the median age of the population is 17.5 years (2010 estimate), our data do not show the magnitude of youth predilection that other studies found.[19] It is concerning that our study only had 8.7% victims under the age of 15 years, suggesting a large reporting or care seeking bias in our study.

A low level of education is the most consistent factor associated with both perpetration and experience of IPV and sexual violence across multiple studies and countries.[25–36] In Mozambique, the average school attendance is 8 years total (9 for men, 7 for women).[19] Comparing our demographics on education, 83.7% of our study population had only finished primary school, or 8 years, which shows a relatively decreased level of education compared to the general population. Populations with low levels of education typically have strong links with the cultural habits, making it hard to recognize domestic violence as a reprehensible act.[37]

Data from multiple settings have shown that while IPV and sexual violence can occur in all socioeconomic groups, women who are living in poverty are disproportionately affected.[8,12,31] The cause of this increased association of poverty and violence is unclear but some theories for the cause include overcrowding, hopelessness, stress and frustration of inadequacy, and financial impossibility to leave a violent or unsatisfactory relationship. In our study population, we found that 94% were earning less than the amount required to live at the poverty level. Our study demonstrates that 68.5% of our population who suffered violence were either not employed or were students and another 25% were employed in jobs that pay below the poverty level. On the whole, about 70% of Mozambicans live below the poverty level (2001 estimate).[19]

The acceptance of violence as a part of culture and family life is still prevalent, especially in developing countries. In many countries, rape and sexual assault of an intimate partner are not considered a crime, and women do not believe forced sex to be rape if they are married to or are co-habiting with the perpetrator.[5] This assertion is backed by WHO's observation that female infanticide, incest, rape, child abuse and prostitution, early marriage and female genital mutilation are among the acts of violence based on gender accepted as standards in many countries.[20] Ilika et al. suggest that victims perceive their abuse as cultural and religious norms, reinforced by prejudice and discrimination, though manifesting itself through actions that cause physical and psychological harm to the victim.[4]

The evaluation of a victim of domestic violence not only includes victim identification, care of the physical injuries and assessing patient safety, but also involves addressing the psychological needs of the victim. Health professionals who have received specialized training on domestic violence are more likely to inquire about violence and are more eager to address the needs of their patient.[37] Meanwhile, women victims of domestic violence identified health professionals as the least able to help in case of aggression by the partner.[38]

Limitations

This study has several important limitations. First, the convenience sampling methodology of this study only captures patients presenting to one of three facilities in Maputo and who self-disclosed violence during a 2-month period. This methodology includes a selection bias excluding those who did not seek care at one of these facilities and who did not self-disclose violence. Secondly, since this is a convenience sampling of a small population and there is minimal data collection at these facilities, we have no comparison population data other than national data. Since the stated objective of the study was to determine the risk factors for FV amongst patients seeking care, the generalizability of these data to the broader population at risk for FV is limited.

CONCLUSION

In Mozambique, the perception that FV is culturally accepted is changing, and FV is increasingly being recognized as a public health problem. This study shows that FV victims presenting for care in Maputo, Mozambique are more likely to be 15-34 year olds with lower education and incomes. With this information, Mozambican officials can begin to increase the knowledge and competence among healthcare workers in order to recognize the specific risk factors for FV and to take the next step in care and secondary prevention.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, editors. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. World report on Violence and Health. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saffioty H. Violência de género: Entre o público e o privado. Presenç da Mulher. 1997;31:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santos A. Violência Doméstica e Saúde da Mulher Negra. Revista Toques. 2001;4:16. [Google Scholar]

- 4.llika A. Women's perception of partner violence in rural Igbo community. Afr J Reprod Health. 2005;9:77–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNICEF. Domestic violence against women and girls. Vol Innocenti Digest. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Moreno C. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. Multi-country study on women's health and domestic ciolence against women. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottemoeller M. Ending violence against women. Populat Rep. 1999;27:1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heilse L, Garcia-Moreno C. Violence by intimate partners. In: Krug EG, editor. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. pp. 87–121. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. World Health Orgainization, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: Taking action and generating evidence. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raj A, Sabarwal S, Decker MR, Nair S, Jethva M, Krishnan S, et al. Abuse from in-laws during pregnancy and post-partum: Qualitative and quantitative findings from low-income mothers of infants in Mumbai, India. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:700–12. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0651-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Normas e Manuais Técnicos, Série Direitos Sexuais e Direitos Reprodutivos. In: Departamento de Acções Programáticas Estratégicas Área Técnica de Saúde da Mulher Prevenção e Tratamento dos Agravos Resultantes da Violência Sexual contra Mulheres e Adolescentes. ed 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jewkes R, Sen P, Garcia-Moreno C. Sexual Violence. In: Krug EG, editor. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. pp. 149–81. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neves O, Silva C, Bartolomeo K. Maputo, Mozambique: 2004. Traumatismos na Cidade de Maputo, Causas e Contexto de Ocorrência. [Google Scholar]

- 14.CDC. Sexual violence prevention: beginning the dialog: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahlberg LL, Drug EG. Violence - a global public health problem. In: Krug EG, editor. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 16.INE. Instituto Nacional de Estatistica Moçambique. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Recenseamento Geral da População 1997-Resultados definitivos. Maputo, Mozambique: Instututo Nacional de Estatística;; 1998. INE. II. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moçambique: Inquérito Demográfico e de Saúde 200 Maputo. Mozambique: Instituto Nacional de Estatística, Ministério da Saúde; 2004. MISAU Ia. [Google Scholar]

- 19.CIA. CIA Worldfact Book: Mozambique. [cited in 2010]. Available from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/mz.html .

- 20.WHO. Integrating Poverty and Gender in to Health Programs 2005. [cited in 2010]. Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/NR/rdonlyres/E517AAA7-E80B-4236-92A1 .

- 21.Black DA. Partner, child abuse risk factors literature review. National Network of Family Resiliency 1999. [cited in 2010]. Available from: http://www.nnh.org/risk .

- 22.Harwell TS, Spence MR. Population surveillance for physical violence among adult men and women, Montana 1998. Am J Prev Med. 2000;33:S114–29. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roman S, Forte T, Cohen MM, Du Mont J, Hyman I. Who is most at risk for intimate partner violence.A Canadian population-based study? J Interpersonal Violence. 2007;22:1495–514. doi: 10.1177/0886260507306566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vest JR, Catlin TK, Chen JJ, Brownson RC. Multistate analysis of factors associated with intimate partner violence. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:156–64. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00431-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ackerson LK, Kawachi I, Barbeau EM, Subramanian SV. Effects of individual and proximate educational context on intimate partner violence: A population-based study of women in India. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:507–14. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boy A, Kulczycki A. What we know about intimate partner violence in the Middle East and North Africa. Violence Against Women. 2008;14:53–70. doi: 10.1177/1077801207311860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyle MH, Georgiades K, Cullen J, Racine Y. Community influences on intimate partner violence in India: Women's education, attitudes towards mistreatment and standards of living. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:691–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown L, Thurman T, Bloem J, Kendall C. Sexual violence in Lesotho. Stud Fam Plan. 2006;37:269–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2006.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan KL. Sexual violence against women and children in Chinese societies. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2009;10:69–85. doi: 10.1177/1524838008327260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dalal K, Rahman F, Jansson B. Wife abuse in rural Bangladesh. J Biosoc Sci. 2009;41:561–73. doi: 10.1017/S0021932009990046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gage AJ. Women's experience of intimate partner violence in Haiti. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:343–64. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeyaseelan L, Sadowski LS, Kumar S, Hassan F, Ramiro L, Vizcarra B. World studies of abuse in the family environment-risk factors for physical intimate partner violence. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2004;11:117–24. doi: 10.1080/15660970412331292342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson KB, Das MB. Spousal violence in Bangladesh as reported by men: Prevalence and risk factors. J Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:977–95. doi: 10.1177/0886260508319368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koenig MA, Stephenson R, Ahmed S, Jejeebhoy SJ, Campbell JC. Individual and contextual determinants of domestic violence in north India. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:132–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin EK, Taft CT, Resick PA. A review of marital rape. Aggression Violent Behav. 2007;12:329–47. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang CS, Lai BP. A review of empirical literature on the prevalence and risk markers of male-on-female intimate partner violence in contemporary China 1987-2006. Aggression Violent Behavior. 2008;13:10–28. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Population Reports, Center for Communication Programs. Vol. 16. Rio de Janeiro: 2000. USAID. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez M, Quiroga S, Bauer H. Breaking the silence: Battered women's perspectives on medical care. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5:153–8. doi: 10.1001/archfami.5.3.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]