Abstract

Background

Recent research suggests that adding a quantity/frequency alcohol consumption measure to diagnoses of alcohol use disorders may improve construct validity of the diagnoses for DSM-V. This study explores the epidemiological impact of including weekly at-risk drinking (WAD) in the DMS-IV diagnostic definition of alcohol dependence via three hypothetical reformulations of the current criteria.

Methods

The sample was the NESARC, a nationally representative sample with 43,093 adults aged >18 in the U.S interviewed with the AUDADIS-IV. The current (DSM-IV) definition of alcohol dependence was compared to four hypothetical alcohol dependence reformulations that included WAD: 1) WAD added as an eighth criteria; 2) WAD required for a diagnosis; 3) adding abuse and dependence criteria together, and including WAD with a 3 out of 12 symptom threshold; 4) adding abuse and dependence criteria together, and including WAD with a 5 out of 12 symptom threshold.

Results

The inclusion of at-risk drinking as an eighth criterion of alcohol dependence has a minimal impact on the sociodemographic correlates of alcohol dependence but substantially increases the prevalence of dependence (from 3.8% to 5.0%). At-risk drinking as a required criterion or as part of a diagnosis that combines abuse with dependence criteria with a higher threshold (5+ criteria) decreases prevalence and has a larger impact on sociodemographic correlates. Blacks, Hispanics, and women are less likely to be included in diagnostic reformulations that include weekly at-risk drinking, whereas individuals with low-income and education are more likely to remain diagnosed.

Conclusions

Including WAD as either a requirement of diagnosis or as an additional criterion would have a large impact on the prevalence of alcohol dependence in the general population. The inclusion of a quantity/frequency requirement may eliminate false positives from studies of alcohol disorder etiology and improve phenotype definition for genetic association studies by reducing heterogeneity in the diagnosis, but may also reduce eligibility for treatment services among women and racial/ethnic minorities compared.

Keywords: at-risk drinking, binge drinking, DSM-V, alcohol dependence, epidemiology

Introduction

As preparations continue for DSM-V, the research agenda for the alcohol use disorders has focused on improving the validity and utility of diagnosis (Helzer et al., 2006,2007 Li et al., 2007a,b). Psychometric, clinical, and epidemiologic research into the implications of potential changes to the diagnosis is timely and necessary for a complete understanding of the consequences of proposed alternations. One of the changes under consideration is the addition of at-risk drinking as a criterion in the next revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental and Behavior Disorders (DSM-V) slated for publication in 2012 (Saha et al., 2007; Li et al., 2007a,b).

Currently, the alcohol diagnoses are defined by a bi-axial concept of disorder encompassing two distinct dimensions: alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence (APA, 1994). Based in part on the work of Edwards and Gross published in 1976 (Edwards, 1986; Edwards & Gross, 1976), each dimension is intended to describe maladaptive patterns of use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress. In DSM-IV, there are seven criteria for the dependence syndrome; these seven criteria are characterized by physiologic and/or psychological symptoms indicative of impaired control over drinking despite the occurrence of negative consequences. Three of seven criteria are necessary for a diagnosis. The decision to retain the threshold at three symptoms over the course of the DSM revisions was made in order to preserve comparability of diagnosis when comparing, for example, DSM-III-R diagnoses to DSM-IV diagnoses (Cottler et al., 1991, 1995). Alcohol abuse is diagnosed using four criteria, encompassing negative consequences to the individual in the social, legal, and occupational domains, with one of four criteria necessary for a diagnosis. Abuse and dependence diagnoses are currently organized hierarchically (i.e., individuals with dependence cannot be diagnosed with abuse even if criteria are met), but are not orthogonal (i.e., they are expected to co-occur in some but not all cases).

Despite explicitly stating that a maladaptive pattern of alcohol use is a necessary condition for diagnosis in the DSM-IV diagnoses of alcohol abuse as well as dependence, specific criteria for a level of consumption considered “maladaptive” have not been included in the diagnostic nosology. Reasons include reliability and validity issues in self-reports of alcohol consumption (Guze et al., 1967; Saha et al., 2007), individual variation in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in alcohol metabolism (Hurley et al., 2002; Li et al., 2001), and cross-cultural variation in normative drinking levels (Greenfield & Kerr, 2008).

Advances in the measurement of alcohol consumption, however, have led to improved reliability and validity of self-reported drinking in the population (Dawson, 2003; Greenfield & Kerr, 2008; Grant et al., 1995, 2003b). As such, high-risk drinking (i.e. a level of drinking that increases the risk of developing an alcohol disorder as well as risk of morbidity and mortality) has been generally defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) as drinking “too much too fast” or “too much too often” (Li et al., 2007a,b). In 2004, NIAAA published guidelines indicating that male drinkers who exceed four drinks per drinking occasion and female drinkers who exceed three drinks per drinking occasion (too much too fast) can be classified as risky drinkers (NIAAA, 2004; 2005). A robust literature affirms that drinking at these levels is predictive not only of the development of alcohol disorders (Hasin et al., 1999a), but also numerous additional adverse physical (Dawson et al., 2005a), mental (Dawson et al., 1996; Hindmarch et al., 1991), and social consequences (Midanik et al., 1996; Russell et al., 2004) across a wide range of age groups (Lang et al., 2007; Rehm et al., 2005; Wechsler and Nelson, 2006).

While alcohol-related harm is associated with at-risk drinking at any frequency, the likelihood of significant physical and psychological consequences increase as frequency of at-risk drinking increases. Thus, a diagnostic cut-off for frequent at-risk drinking is not obvious. Saha et al. (2007) used Item Response Theory (IRT) analysis to empirically examine the addition of a at-risk drinking item as a putative additional diagnostic criterion, and compared three at-risk drinking cutoffs for the previous 12 months: at least once, at least monthly, and at least weekly. Based on the IRT results concerning current diagnostic criteria among current (last 12 months) drinkers in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), at-risk drinking (5+ drinks for men, 4+ drinks for women) once per week or more was recommended for inclusion as an alcohol disorder criterion in DSM-V (Saha et al., 2007; Li et al., 2007a,b). Below, for simplicity, we refer to Weekly At-risk Drinking as “WAD.”

Further support for the inclusion of WAD comes from recent psychometric analyses of the alcohol abuse and dependence criteria. These analyses have suggested that these disorders are not distinct entities; instead, evidence supports an underlying continuum of alcohol severity across a variety of samples and populations (Kahler & Strong, 2006; Kreuger et al., 2004; Hasin et al., 2006; Martin et al., 2006; Moss et al., 2008; Proudfoot et al., 2006; Saha et al., 2006). Suggestions have been made that the diagnostic nosology would benefit etiologic research by including items reflecting the less severe end of the continuum of alcohol disorders. Since at-risk drinking is prevalent in the general population (Keyes et al., 2008a), especially among young people, it has been suggested that an at-risk drinking criterion such as WAD may be an appropriate candidate to represent the milder end of the alcohol disorder continuum (Saha et al., 2006, 2007).

Despite this interest in adding WAD as a DSM-V criterion of an alcohol disorder, the manner in which it would be included has not been clarified. WAD could be made a requirement for the categorical diagnosis, or could be included as one additional criterion in the existing criteria list. A WAD requirement to make the diagnosis might improve specificity by including only individuals who exceed established drinking guidelines (reducing false positives). However, such a requirement might also decrease sensitivity by excluding individuals with alcohol problems who are sensitive to alcohol effects, and who therefore do not drink large quantities (increasing false negatives). The inclusion of WAD must also be evaluated in the context of other potential changes to the diagnosis. For instance, DSM-V will likely provide a dimensional representation of alcohol dependence (Helzer et al., 2006); however, a categorical form of the diagnosis will remain necessary for treatment qualification and third-party reimbursement purposes.

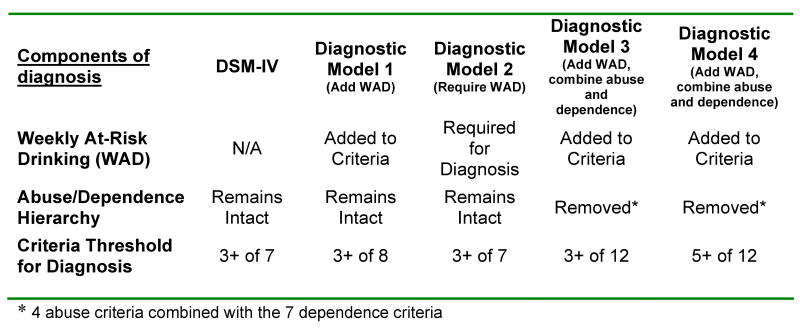

To address these issues, we examined the impact of adding WAD to the diagnosis of alcohol dependence by modeling the effects of this addition on the prevalence and descriptive epidemiology of the disorder. We do not seek to advocate for any particular change to the DSM definition of alcohol dependence (i.e., this is not a validity study), but rather to explore the potential consequences of diagnostic reformulations. We examined four hypothetical reformulations of the diagnosis that added WAD. Diagnostic Model 1 consisted of adding WAD as an eighth criterion of alcohol dependence. The threshold for diagnosis remained at the DSM-IV level; three or more criteria were necessary. Diagnostic Model 2 consisted of requiring WAD for a diagnosis of alcohol dependence. The alcohol dependence diagnosis was otherwise unmodified; three of seven of the current DSM-IV criteria remained necessary. Diagnostic Model 3 consisted of combining the alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence, adding WAD to the list of 7 dependence criteria and 4 abuse criteria, and requiring 3 of the 12 total possible criteria to make a diagnosis of an alcohol disorder. Diagnostic Model 4 also combined abuse and dependence criteria and added WAD, but required 5 of the 12 possible criteria for a diagnosis. Figure 1 shows a summary of current DSM-IV alcohol dependence diagnosis and four hypothetical reformulations incorporating WAD.

Figure 1.

The existing DSM-IV alcohol dependence diagnosis and four hypothetical reformulations that incorporate Weekly At-Risk Drinking (WAD).

With these four diagnostic models, the present study had two aims: Aim 1. To examine the prevalence and demographic correlates of Diagnostic Models 1 through 4. We present these findings alongside current national estimates (Hasin et al., 2007) for comparison. Aim 2. To estimate the proportion of DSM-IV alcohol dependence cases retained under the diagnostic models as well as the proportion of newly diagnosed cases. In addition, to explore demographic characteristics of respondents with alcohol dependence under diagnostic reformulations compared to those diagnosed under DSM-IV.

Methods

Sample design and procedures

This sample consists of participants in the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a nationally representative United States survey of civilian non-institutionalized participants aged 18 and older, interviewed in person. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) sponsored the study and supervised the fieldwork, conducted by the U.S. Bureau of the Census. The research protocol, including informed consent procedures, received full ethical review and approval from the U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Office of Management and Budget. Young adults, Hispanics, and African-Americans were oversampled for adequate representation; the overall response rate was 81%. Further details of the sampling frame and demographics of the sample (Grant et al., 2003a; Grant et al., 2004a; Grant et al., 2007b) and of the interviews, training, and field quality control are described elsewhere (Grant et al., 2003b; Grant et al., 2004b).

Measures

Alcohol abuse and dependence

DSM-IV diagnosis of alcohol abuse and dependence were made using The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS-IV (Grant et al., 2003a)). This structured diagnostic interview was designed for administration by extensively trained lay interviewers and was developed to advance measurement of substance use and mental disorders in large-scale surveys. The interview includes 36 symptom questions to operationalize DSM-IV criteria for diagnoses of alcohol abuse and dependence (APA, 1994). Diagnoses were established explicitly following the DSM-IV. For the present analyses, current diagnosis of alcohol dependence was considered; that is, a clustering of thee or more alcohol dependence criteria in the prior 12-month period. Importantly, the AUDADIS-IV provides complete coverage of DSM-IV alcohol dependence as well as abuse by assessing all criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence non-hierarchically and independently, avoiding problems in coverage of other survey instruments (Grant et al., 2007a; Hasin & Grant, 2004).

The reliability of the alcohol use disorder diagnoses in the AUDADIS-IV has been extensively documented in clinical and general population samples (Chatterji et al., 1997; Grant et al., 2003a; Grant et al., 1995; Ruan WJ et al., 2008; Hasin et al., 1997a); test-retest reliability ranges from good to excellent (K = 0.70-0.84). The convergent, discriminative and construct validity of AUDADIS-IV alcohol use disorder criteria and diagnoses were tested in community samples (Hasin & Paykin, 1999; Hasin et al., 1990; Hasin et al., 1999b; Hasin et al., 1997b; Hasin et al., 2003) and in international samples (Cottler et al., 1997; Hasin et al., 1997c; Nelson et al., 1999; Pull et al., 1997; Ustun et al., 1997; Vrasti et al., 1998) and shown to be good to excellent. Further, clinical reappraisals documented good criterion validity of DSM-IV alcohol use disorder diagnoses (K = 0.60-0.76, Canino et al., 1999). While the reliability and validity of alcohol abuse has been more variable than that of dependence, alcohol abuse when assessed non-hierarchically (independently of alcohol dependence), as is done in the AUDADIS-IV, has adequate reliability (Canino et al., 1999; Chatterji et al., 1997; Hasin et al., 2006). Further description of the derivation and psychometric properties of alcohol abuse and dependence diagnoses have been provided in detail elsewhere (Grant et al., 2007a; Grant et al., 2007b; Hasin et al., 2007; Hasin & Grant, 2004).

At-risk drinking

The measurement of at-risk drinking in the AUDADIS-IV takes the graduated frequency (“GF”) approach; briefly, the GF approach measures self-reported alcohol consumption by asking how often the respondent drank a certain number of standard drinks per day during a specified reference period. This is typically operationalized by beginning with the maximum number possible (e.g., how often respondent drank their maximum number of total standard drinks during the reference period) and subsequently asks about the frequency of drinking a lower number of drinks. At-risk drinking is assessed within the prior 12-month period. All respondents are asked how often they consumed 5 or more drinks in a single day (“During the last 12 months, about how often did you drink 5 or more drinks in a single day”); women are then also asked how often they consumed four or more drinks in a single day. All respondents are given 11 categories for response, beginning with the most frequent (i.e., every day). Organizing responses from most to least frequent is believed to elicit more valid responses because respondents believe that the higher frequencies are more indicative of normalcy (Dawson and Room, 2000). The past 12-month reference period has been shown to capture the highest proportion of both intermittent heavy drinkers and infrequent light drinkers as compared with shorter time periods (e.g., past 30-days or past 7-days) (Rehm et al., 1999; Stockwell et al., 2004). In the NESARC sample, ICCs associated with the frequency of 5+ drinks were good for the past 12-month measure in a test-retest reliability study (ICC=0.69, Grant et al., 2003b). The reliability of frequency of 4+ drinks in women has not been evaluated. Further information on the psychometric properties of the GF approach including a detailed discussion of the advantages and limitations of this measurement technique as compared to others can be found in Dawson (2003) and Greenfield and Kerr (2008).

Statistical analysis

For the first aim, the weighted prevalence of disorders produced by each hypothetical diagnosis was estimated using crosstabs, both in the whole sample and by demographic characteristics. Logistic regressions were used to estimate the odds of alcohol dependence by demographic characteristics for each of the diagnostic models. Models controlled for all demographic predictors simultaneously. This analysis was conducted in the total NESARC sample (N=43,098). For the second aim, contingency tables were constructed to estimate the proportion of alcohol dependence cases under diagnostic reformulations among those with and without a DSM-IV alcohol dependence diagnosis. Additionally, we subset the dataset to determine demographic differences between newly-defined cases as compared with existing DSM-IV cases (N=1,484). All analyses were conducted using SUDAAN to adjust for the complex sampling design of the NESARC (Research Triangle Institute, 2004).

Results

Diagnostic Model 1. WAD added as an 8th criterion of alcohol dependence, diagnostic threshold unmodified from DSM-IV

Under Diagnostic Model 1, the prevalence of past-year alcohol dependence increases from 3.8% in the current national estimate to 5.0% (see Table 1). This represents a 31.6% increase in the prevalence of alcohol dependence.

Table 1. Prevalence of 12-Month alcohol dependence in NESARC (N=43,098) by sociodemographic characteristics: current DSM-IV definition versus three hypothetical definitions.

| Characteristics | Current DSM-IV definition** (N=1,484) % (SE) |

Diagnostic model 1: at-risk drinking is added as an eighth criterion; threshold for diagnosis remains three of eight (N=1,978) % (SE) |

Diagnostic model 2: at-risk drinking is a necessary condition for a diagnosis (N=916) % (SE) |

Diagnostic model 3: abuse dependence criteria added together; at-risk drinking added as an criterion; threshold for diagnosis is three of twelve criteria (N=1,971) % (SE) |

Diagnostic model 4: abuse dependence criteria added together; at-risk drinking added as an criterion; threshold for diagnosis is five of twelve criteria (N=791) % (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 3.8 (0.14) | 5.0 (0.2) | 2.5 (0.1) | 5.0 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.1) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 5.4 (0.21) | 7.2 (0.3) | 3.8 (0.2) | 7.2 (0.3) | 3.2 (0.2) |

| Female | 2.3 (0.13) | 3.0 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.1) | 3.0 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.1) |

| Race-ethnicity | |||||

| White | 3.8 (0.16) | 5.1 (0.2) | 2.6 (0.1) | 5.0 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.1) |

| Black | 3.6 (0.29) | 4.7 (0.3) | 1.9 (0.2) | 4.5 (0.3) | 1.8 (0.2) |

| Native American | 6.4 (1.17) | 7.2 (1.3) | 5.4 (1.1) | 7.7 (1.2) | 5.2 (1.1) |

| Asian | 2.4 (0.38) | 3.3 (0.5) | 1.5 (4.3) | 3.3 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.3) |

| Hispanic | 4.0 (0.44) | 5.4 (0.5) | 2.3 (0.3) | 5.5 (0.5) | 2.1 (0.3) |

| Age | |||||

| 18-29 | 9.2 (0.41) | 11.8 (0.5) | 6.1 (0.4) | 12.0 (0.5) | 5.4 (0.3) |

| 30-44 | 3.8 (0.23) | 5.2 (0.3) | 2.3 (0.2) | 5.0 (0.3) | 1.9 (0.2) |

| 45-64 | 1.9 (0.15) | 2.6 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.1) | 2.5 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.1) |

| 65+ | 0.2 (0.06) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married/cohabiting | 2.1 (0.12) | 2.9 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.1) | 2.9 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.1) |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 3.7 (0.30) | 4.6 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.3) | 4.7 (0.3) | 2.2 (0.2) |

| Never married | 9.0 (0.44) | 11.7 (0.5) | 6.0 (0.4) | 11.4 (0.5) | 5.2 (0.3) |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 4.0 (0.33) | 5.2 (0.4) | 2.8 (0.3) | 5.1 (0.4) | 2.3 (0.3) |

| High school | 3.7 (0.24) | 5.1 (0.3) | 2.8 (0.2) | 4.8 (0.3) | 2.2 (0.2) |

| Some college or higher | 3.8 (0.16) | 5.0 (0.2) | 2.2 (0.1) | 5.1 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.1) |

| Personal Income | |||||

| $0-19,999 | 4.5 (0.21) | 5.7 (0.2) | 2.9 (0.2) | 5.5 (0.2) | 2.6 (0.2) |

| $20,000-34,999 | 4.0 (0.27) | 5.5 (0.3) | 2.7 (0.2) | 5.5 (0.3) | 2.2 (0.2) |

| $35,000-69,999 | 2.9 (0.20) | 4.0 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.2) | 4.2 (0.2) | 1.5 (0.2) |

| $70,000+ | 2.2 (0.33) | 2.8 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.2) | 3.1 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.2) |

| Urbanicity | |||||

| Urban | 3.8 (0.15) | 5.0 (0.2) | 2.4 (0.1) | 4.9 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.1) |

| Rural | 4.0 (0.31) | 5.3 (0.4) | 2.8 (0.3) | 5.4 (0.4) | 2.5 (0.2) |

| Region | |||||

| Northeast | 3.5 (0.29) | 4.6 (0.3) | 2.4 (0.3) | 4.6 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.2) |

| Midwest | 4.6 (0.37) | 6.1 (0.4) | 3.0 (0.3) | 6.1 (0.5) | 2.7 (0.3) |

| South | 3.1 (0.21) | 4.2 (0.3) | 2.1 (0.2) | 4.2 (0.3) | 1.8 (0.2) |

| West | 4.3 (0.27) | 5.6 (0.3) | 2.7 (0.2) | 5.6 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.2) |

Table 2 shows the odds of alcohol dependence by demographic correlates, reformulated as Diagnostic Model 1 and also according to DSM-IV criteria for comparative purposes. Under Diagnostic Model 1, low-middle income ($20,000-34,999) is a statistically significant predictor compared to high income (OR=1.7); under DSM-IV, low-middle income is not a significant predictor of diagnosis. All other demographic correlates are similar in direction, magnitude, and statistical significance to the published DSM-IV correlates.

Table 2. Adjusted* odds ratios (ORs) of 12-Month alcohol dependence by sociodemographic characteristics: current DSM-IV definition versus three hypothetical definitions.

| Characteristics | Current DSM-IV definition** (N=1,484) OR (95% C.I.) |

Diagnostic model 1: at-risk drinking is added as an eighth criterion; threshold for diagnosis remains three of eight (N=1978) OR (95% C.I.) |

Diagnostic model 2: at-risk drinking is a necessary condition for a diagnosis (N=916) OR (95% C.I.) |

Diagnostic model 3: abuse dependence criteria added together; at-risk drinking added as an criterion; threshold for diagnosis is three of twelve criteria (N=1,971) % (SE) |

Diagnostic model 4: abuse dependence criteria added together; at-risk drinking added as an criterion; threshold for diagnosis is five of twelve criteria (N=791) % (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 2.5 (2.10-3.00) | 2.6 (2.29-2.92) | 3.3 (2.69-3.92) | 2.6 (2.29-2.92) | 3.0 (1.59-3.65) |

| Female | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Race-ethnicity | |||||

| White | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Black | 0.7 (0.54-0.95) | 0.7 (0.59-0.85) | 0.5 (0.41-0.73) | 0.7 (0.58-0.84) | 0.6 (0.47-0.85) |

| Native American | 1.6 (0.91-2.65) | 1.3 (0.89-1.96) | 1.9 (1.21-3.03) | 1.5 (1.05-2.11) | 2.3 (1.44-3.62) |

| Asian | 0.5 (0.30-0.75) | 0.5 (0.37-0.68) | 0.5 (0.29-0.74) | 0.5 (0.35-0.70) | 0.4 (0.22-0.69) |

| Hispanic | 0.7 (0.48-0.91) | 0.7 (0.57-0.85) | 0.5 (0.40-0.72) | 0.7 (0.59-0.90) | 0.6 (0.47-0.83) |

| Age | |||||

| 18-29 | 41.9 (20.66-85.04) | 34.9 (23.32-53.13) | 45.7 (24.08-86.72) | 40.9 (26.54-62.88) | 39.1 (19.86-76.91) |

| 30-44 | 22.1 (11.23-43.48) | 19.6 (13.24-28.92) | 23.8 (12.71-44.53) | 20.2 (13.35-30.57) | 18.7 (9.58-36.57) |

| 45-64 | 10.3 (5.19-20.40) | 9.3 (6.20-14.01) | 12.0 (6.44-22.33) | 9.3 (6.04-14.24) | 8.4 (4.32-16.31) |

| 65+ | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married/cohabiting | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 3.1 (2.30-4.07) | 2.7 (2.24-3.27) | 3.3 (2.59-4.32) | 2.9 (2.39-3.49) | 3.6 (2.75-4.83) |

| Never married | 2.1 (1.70-2.71) | 2.2 (1.86-2.52) | 2.3 (1.85-2.82) | 2.0 (1.75-2.36) | 2.2 (1.71-2.78) |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 1.1 (0.85-1.47) | 1.1 (0.94-1.35) | 1.3 (1.03-1.72) | 1.1 (0.89-1.32) | 1.3 (1.03-1.63) |

| High school | 0.9 (0.76-1.15) | 1.0 (0.86-1.11) | 1.2 (0.97-1.42) | 0.9 (0.80-1.06) | 1.0 (0.84-1.25) |

| Some college or higher | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Personal Income | |||||

| $0-19,999 | 1.8 (1.13-2.82) | 1.8 (1.36-2.46) | 2.5 (1.51-3.98) | 1.6 (1.19-2.03) | 2.7 (1.65-4.36) |

| $20,000-34,999 | 1.5 (0.98-2.39) | 1.7 (1.27-2.31) | 2.2 (1.39-3.50) | 1.5 (1.17-2.00) | 2.2 (1.34-3.56) |

| $35,000-69,999 | 1.2 (0.76-1.92) | 1.3 (0.97-1.77) | 1.6 (0.97-2.71) | 1.3 (0.95-1.69) | 1.7 (1.01-2.70) |

| $70,000+ | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Urbanicity | |||||

| Urban | 0.9 (0.72-1.19) | 0.9 (0.79-1.09) | 0.9 (0.70-1.12) | 0.9 (0.74-1.03) | 0.85 (0.68-1.06) |

| Rural | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Region | |||||

| Northeast | 0.8 (0.62-1.10) | 0.8 (0.70-1.00) | 0.9 (0.68-1.13) | 0.8 (0.69-1.01) | 0.7 (0.50-0.90) |

| Midwest | 1.0 (0.76-1.33) | 1.0 (0.86-1.27) | 1.0 (0.76-1.26) | 1.0 (0.84-1.27) | 1.0 (0.74-1.34) |

| South | 0.7 (0.52-0.89) | 0.7 (0.60-0.87) | 0.7 (0.56-0.91) | 0.7 (0.59-0.86) | 0.7 (0.52-0.86) |

| West | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

Models controlled for sex, race-ethnicity, age, marital status, education, personal income, urbanicity, and region

Table 3 shows the proportion of those with and without DSM-IV alcohol dependence that would be diagnosed under Model 1. All individuals diagnosed with alcohol dependence under DSM-IV criteria remain diagnosed. A further 1.3% of individuals currently undiagnosed via DSM-IV would receive a diagnosis, representing the addition of 494 cases to the existing 1,484.

Table 3. Sensitivity and specificity of reformulated alcohol dependence diagnoses, compared to DSM-IV standard.

| DSM-IV diagnosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | ||

| Diagnostic model 1 | Present | 100.0 | 1.3 |

| Absent | 0.0 | 98.7 | |

| Diagnostic model 2 | Present | 65.1 | 0.0 |

| Absent | 34.9 | 100.0 | |

| Diagnostic model 3 | Present | 100.0 | 1.2 |

| Absent | 0.0 | 98.8 | |

| Diagnostic model 4 | Present | 54.3 | 0.0 |

| Absent | 45.7 | 100.0 | |

Comparing these 494 cases to the existing 1,484 DSM-IV diagnosed cases, there were no statistically significant differences in the demographic characteristics between these groups.

Diagnostic Model 2. WAD required for alcohol dependence diagnosis, which was otherwise unmodified from DSM-IV

Under Diagnostic Model 2, the prevalence of past-year alcohol dependence decreases from 3.8% in the current national estimate to 2.5% (see Table 1). This represents a 34% decrease in the prevalence of alcohol dependence.

Table 2 shows the odds of alcohol dependence by demographic correlates in the full sample of current drinkers reformulated as Diagnostic Model 2 and also according to DSM-IV criteria for comparative purposes. Under Diagnostic Model 2, Native American race/ethnicity is a statistically significant predictor compared to Whites (OR=1.9), a result not found under DSM-IV. Additionally, less than high school education (OR=1.3) and low-middle income OR=2.2) become statistically significant predictors of diagnosis, results not found under DSM-IV. All other demographic correlates are similar in direction, magnitude, and statistical significance to published DSM-IV correlates.

Table 3 shows the proportion of those with and without DSM-IV alcohol dependence that would be diagnosed under Model 2. Among individuals with current DSM-IV alcohol dependence (N=1,484), only 65.1% would still meet criteria for diagnosis under Diagnostic Model 2, which is more restrictive than DSM-IV because of the additional 5+/4+ at-risk drinking requirement. No individuals without a DSM-IV diagnosis would meet criteria under Diagnostic Model 2. This represents a decrease of 916 cases from the existing 1,484.

Comparing the remaining 568 cases retained to the 916 DSM-IV diagnosed cases dropped from the diagnosis, the smaller group of re-defined cases under Diagnostic Model 2 were predicted by male sex (OR=2.0, 95% C.I. 1.44-2.86), less than a high school education (OR=1.6, 95% C.I. 1.12-2.39) or high school education (OR=1.9, 95% C.I. 1.37-2.54) compared to some college or higher, and low (OR=2.0, 95% C.I. 1.03-4.39) or middle- low (OR=2.6, 95% C.I. 1.20-5.79) personal income compared to high personal income. Individuals of black (OR=0.5, 95% C.I. 0.33-0.76) or Hispanic (OR=0.6, 95% C.I. 0.39-0.85) race/ethnicity are less likely to be defined as cases under Diagnostic Model 2 compared to Whites.

Diagnostic Model 3: alcohol abuse and dependence criteria combined, WAD added, 3 of the 12 total possible criteria required to make a diagnosis

Under Diagnostic Model 3, the prevalence of past-year alcohol dependence increases from 3.8% in the current national estimate to 5.0% (see Table 1). This represents a 31.6% increase in the prevalence of alcohol dependence.

Table 2 shows the odds of alcohol dependence by demographic correlates, reformulated as Diagnostic Model 3 and also according to DSM-IV criteria for comparative purposes. Under Diagnostic Model 3, low-middle income ($20,000-34,999) is a statistically significant predictor compared to high income (OR=1.5); under DSM-IV, low-middle income is not a significant predictor of diagnosis. All other demographic correlates are similar in direction, magnitude, and statistical significance to the published DSM-IV correlates.

Table 3 shows the proportion of those with and without DSM-IV alcohol dependence that would be diagnosed under Model 3. All individuals diagnosed with alcohol dependence under DSM-IV criteria remain diagnosed; 1.2% of individuals currently undiagnosed via DSM-IV would receive a diagnosis, representing 487 cases are added to the existing 1,484.

Comparing these 487 cases to the existing 1,484 DSM-IV diagnosed cases, newly defined cases were less likely to be of Hispanic race/ethnicity (OR=0.67, 95% C.I. 0.46-0.97).

Comparison of newly diagnosed cases in Models 1 and 3

Under Model 1, 484 cases would be added to the diagnosis, while under Model 3, 487 cases would be added to the diagnosis. Although these represents a difference of only 3 total cases, the individuals newly diagnosed under each model are not completely overlapping. While 1,696 individuals would be diagnosed under either Model 1 or 3, among the 1,978 cases diagnosed under Model 1, there are 282 not diagnosed under Model 3. Among the 1,971 cases diagnosed under Model 3, there are 275 not diagnosed under Model 1.

Diagnostic Model 4: alcohol abuse and dependence criteria combined, WAD added, 5 of the 12 total possible criteria required to make a diagnosis

Under Diagnostic Model 4, the prevalence of past-year alcohol dependence decreases from 3.8% in the current national estimate to 2.1% (see Table 1). This represents a 44.7% decrease in the prevalence of alcohol dependence.

Table 2 shows the odds of alcohol dependence by demographic correlates, reformulated as Diagnostic Model 4 and also according to DSM-IV criteria for comparative purposes. Under Diagnostic Model 4, Native American race/ethnicity is a statistically significant predictor compared to Whites (OR=2.3), a result not found under DSM-IV. Additionally, less than high school education (OR=1.3), low-middle income (OR=2.2), and upper-middle income (OR=1.7) become statistically significant predictors of diagnosis; results not found under DSM-IV. Finally, individuals residing in the Northeast have a lower prevalence of diagnosis compared to individuals in the West (OR=0.7); results not found under DSM-IV. All other demographic correlates are similar in direction, magnitude, and statistical significance as published DSM-IV correlates.

Table 3 shows the proportion of those with and without DSM-IV alcohol dependence that would be diagnosed under Model 4. Among individuals with current DSM-IV alcohol dependence (N=1,484), only 54.3% would still meet criteria for diagnosis under Diagnostic Model 4, which is more restrictive than DSM-IV because of the requirement of 5 out of 12 criteria. No individuals without a DSM-IV diagnosis would meet criteria under Diagnostic Model 2. This represents a decrease of 782 cases from the existing 1,484.

Comparing the remaining 702 cases to the 782 DSM-IV diagnosed cases dropped from the diagnosis, the smaller group of re-defined cases under Diagnostic Model 4 were predicted by male sex (OR=1.5, 95% C.I. 1.11-1.92), Native American race ethnicity (OR=3.5, 95% C.I. 1.35-8.84) compared to Whites, and low (OR=2.3, 95% C.I. 1.20-4.51) or middle- low (OR=2.1, 95% C.I. 1.06-4.11) personal income compared to high personal income.

Discussion

The present study documents changes in the prevalence and correlates of the alcohol dependence diagnosis after four hypothetical reformulations that include weekly at-risk drinking (WAD) in the diagnostic criteria. Adding WAD as a criterion (either as an eighth criterion of alcohol dependence or as a twelfth criterion of an abuse/dependence combination) and leaving the threshold for diagnosis at three or more criteria increases the prevalence of diagnosis by 31.6% (3.8% to 5.0%), but has a minimal impact on the demographic correlates of diagnosis. Hispanics currently diagnosed with alcohol dependence via DSM-IV would be less likely to be cases under Diagnostic Model 3. In contrast, we found that requiring WAD for a diagnosis of alcohol dependence would have a significant impact on the epidemiology of alcohol dependence. Approximately one third of individuals currently diagnosed with alcohol dependence do not report weekly at-risk drinking; thus, one third would not receive a diagnosis if WAD is added as a necessary condition for diagnosis with alcohol dependence. Native Americans and those at low income/education levels would be more likely to be diagnosed with alcohol dependence (compared to national estimates in Hasin et al., 2007), but Blacks and Hispanics would be less likely to be designated as cases of alcohol dependence if at-risk drinking were a necessary condition for diagnosis. Finally, adding abuse/dependence symptoms and requiring 5 of 12 criteria for diagnosis would reduce the prevalence of alcohol dependence from 3.8% to 2.1%. Predictors of new case definition in the diagnosis include being male, Native American, and low income. Not shown, we also examined demographic correlates at each potential threshold, from 3 out of 12 criteria to 12 out of 12 criteria. As expected, the prevalence of disorder decreases with each increase in number of criteria required for diagnosis. In addition, the patterns that we have presented here remain qualitatively similar, but become more pronounced with each increase in the threshold requirement.

The DSM is used in a wide variety of clinical and research settings and by a variety of different professionals within those settings. Accordingly, the implications of these findings vary by the perceived utility of the specific content of diagnosis among these different DSM users; some users may benefit from more inclusive criteria whereas others may see value in a more specific and stringent set of criteria (Hasin et al., 2003). Adding WAD as an additional criterion to the current list would allow individuals to meet criteria for DSM-diagnosed alcohol dependence through more combinations of the DSM criteria, potentially increasing the number of eligible clients for treatment services. Under DSM-IV, there are 98 combinations of the seven criteria through which an individual can qualify for a diagnosis; under Diagnostic Model 1, there are 210 combinations of the eight criteria through which an individual can qualify. These possible combinations are exponentially greater under Diagnostic Model 3. Thus, this model may appeal to service providers by increasing the eligibility for treatment of a greater number of patients, e.g. at-risk drinkers in medical settings with two dependence symptoms for whom provider time would not now be reimbursed.

Increasing the number of individuals diagnosed with alcohol dependence, however, may also create a more etiologically heterogeneous diagnostic group. Increased heterogeneity increases the difficulty of detecting associations between causal variables and the disorder. Thus, a set of diagnostic criteria that reduces heterogeneity, such as a set of AUD criteria that requires at-risk drinking, may be more useful to pharmacological and genetic alcohol researchers. Consistent with this, the inclusion criteria for some large treatment trials of alcohol dependence have required a minimum quantity/frequency level in addition to a standard DSM-IV alcohol dependence diagnosis (e.g., Anton et al., 2006). Additionally, while many genetic studies use DSM-IV to define phenotypes (Li, 2000; Edenberg et al., 2006; Luo et al., 2005, 2006), other studies use measures such as maximum drinks per drinking occasion (Hasin et al., 2002; Shea et al., 2001; Carr et al., 2002) or frequency of at-risk drinking (Covault et al., 2007). A diagnosis that combines alcohol dependence with a requirement for WAD (i.e., Diagnostic Model 2) may results in less diagnostic heterogeneity in the qualifying individuals. If this is the case, requiring at-risk drinking may reduce the signal to noise ratio in the detection of genetic associations, which would be facilitated in cross-study comparisons by a standard definition of WAD such as the one we investigated.

Regardless of the diagnostic reformulation, the inclusion of WAD has little effect on socio-demographic correlates of alcohol dependence; most demographics correlates described under DSM-IV remain constant in direction and magnitude under diagnostic reformulations (e.g., Blacks and Hispanics have a lower prevalence of alcohol dependence compared to Whites). Comparing those retained versus those not retained among those with DSM-IV alcohol dependence, however, Black and Hispanics are less likely to qualify for a diagnosis under the reformulations. Recent studies have indicated little difference in the prevalence of alcohol treatment utilization between Blacks and Whites (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008; Keyes et al., 2008b), while Hispanics with alcohol disorders are less likely to utilize alcohol treatment services (Schmidt et al., 2007). The inclusion of a at-risk drinking indicator as a necessary component of the alcohol dependence diagnosis may impact these disparities in treatment utilization. Additionally, it is well-documented that alcohol dependent women exhibit higher rates of physical illness compared to alcohol dependent men including a higher overall mortality rate (Holman et al., 1996), cirrhosis of the liver (Deal & Gavaler, 1994; Morgan & Sherlock, 1977), myocardial infarction (Hanna et al. 1997; Urbano-Marquez et al., 1995), and neurological damage (Schweinsburg et al., 2003; Hommer et al., 2001). Heavy alcohol use is also implicated in the etiology of breast cancer (Smith-Warner et al., 1998; Key et al., 2006). Thus, changes the diagnosis may have an indirect effect on rates of physical illness among women through the lack of treatment services qualification.

Study limitations are noted. As in all large-scale behavioral surveys, the information presented here is based on self-report. Recall bias is always an issue in self-report surveys; however, the focus on past 12-month at-risk drinking and alcohol dependence was chosen explicitly to minimize potential recall issues. Another potential limitation includes the cross-sectional design; by design, we report prevalence estimates (i.e., number of existing cases of alcohol dependence at a particular point in time) and not incidence estimates (i.e., number of new onset cases of alcohol dependence over a circumscribed period of time). There could be different associations between at-risk drinking and incident cases of alcohol dependence compared with prevalence estimates or lifetime diagnoses. Accordingly, when data from a 3-year follow-up of NESARC participants become available, they will offer a rich source of information to further investigate the relationships documented here and the stability in the general population. Finally, individuals are asked to report about drinking quantity and frequency in the entire past year timeframe, and asked about dependence symptoms in the past year time frame as well. It is possible that some individuals with alcohol dependence reduced their drinking during the year due to the recognition of problematic alcohol-related behavior; these individuals may report alcohol dependence symptoms but no weekly at-risk drinking.

The purpose of this study was to contribute to knowledge regarding the inclusion of an alcohol quantity/frequency measure in the diagnostic criteria for alcohol use disorders, for DSM-V and for a general understanding of the definitions of alcohol use disorders. This is not, however, a validation study. Thus, conclusions about the appropriate choice for the future of the DSM would be speculative at this time; validation study designs are needed in order to empirically test each of these options and we are currently preparing for such studies. The conclusions that we are able to draw from these data, however, include that the addition of at-risk drinking as an eighth criterion of alcohol dependence would have little impact on the sociodemographic correlates of alcohol dependence but would substantially increase its prevalence. At-risk drinking as a required criterion or as part of a relaxed abuse/dependence hierarchy with a five symptom threshold for diagnosis would have a larger impact on the sociodemographics of alcohol dependence, most likely affecting diagnosis among minority racial/ethnic groups, women, and low income individuals.

These results should be considered in the context of the alcohol abuse diagnosis, both the DSM-IV formulation and the ICD-10 harmful use formulation. If the DSM-V includes axes for abuse and dependence (rather than a primary dimensional representation), it would be valuable to test whether at-risk drinking might have better validity as apart of the abuse axis as compared to the dependence axis. Studies demonstrating the reliability and construct validity of diagnostic criteria that include at-risk drinking measures are necessary as progress toward DSM-V and a better understanding of alcohol use disorders continues.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (K05 AA014223, Hasin), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (RO1 DA018652, Hasin), a fellowship from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32 MH013043-36, Keyes), and support from New York State Psychiatric Institute. A version of this paper was presented at the 2008 meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism in Washington, D.C., where it received the Enoch Gordis prize for student psychosocial research. The authors wish to thank Sarah Braunstein and Ann Madsen for helpful comments on previous drafts of this manuscript.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. American Psychopathological Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, O'Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, Gastfriend DR, Hosking JD, Johnson BA, LoCastro JS, Longabaugh R, Mason BJ, Mattson ME, Miller WR, Pettinati HM, Randall CL, Swift R, Weiss RD, Williams LD, Zweben A. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino GJ, Bravo M, Ramirez R, Febo V, Fernandez R, Hasin DS. The Spanish Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability and concordance with clinical diagnoses in a Hispanic population. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60(6):790–799. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr L, Foroud T, Stewart T, Castellucio P, Edenberg H, Li T. Influence of ADH1B (2002) polymorphism on alcohol use and its subjective effects in a Jewish population. Am J Med Genet. 112(2):138–143. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterji S, Saunders JB, Vrasti R, Grant BF, Hasin D, Mager D. Reliability of the alcohol and drug modules of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule—Alcohol/Drug-Revised (AUDADIS-ADR): an international comparison. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47(3):171–185. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Helzer JE, Mager D, Spitznagel EL, Compton WM. Agreement between DSM-III and III-R substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1991;29(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(91)90018-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Schuckit MA, Helzer JE, Crowley T, Woody G, Nathan P, Hughes J. The DSM-IV field trial for substance use disorders: major results. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;38(1):59–69. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)01091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Grant BF, Blaine J, Mavreas V, Pull C, Hasin D, Compton WM, Rubio-Stipec M, Mager D. Concordance of DSM-IV alcohol and drug use disorder criteria and diagnoses as measured by AUDADIS-ADR, CIDI and SCAN. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47(3):195–205. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covault J, Tennen H, Armeli S, Conner TS, Herman AI, Cillesse AH, Kranzler HR. Interactive Effects of the Serotonin Transporter 5-HTTLPR Polymorphism and Stressful Life Events on College Student Drinking and Drug Use. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(5):609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA. Methodological Issues in Measuring Alcohol Use. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27(1):18–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Archer LD, Grant BF. Reducing alcohol-use disorders via decreased consumption: a comparison of population and high-risk strategies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;42:39–47. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Li TK. Quantifying the risks associated with exceeding recommended drinking limits. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005a;29:902–908. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164544.45746.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Room R. Towards agreement on ways to measure and report drinking patterns and alcohol-related problems in adult general population surveys: the Skarpö Conference overview. J Subst Abuse. 2000;12:1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deal ST, Gavaler JS. Are women more susceptible than men to alcohol-induced cirrosis? Alcohol Health Res World. 1994;18:189–191. [Google Scholar]

- Edenberg HJ, Xuei X, Chen HJ, Tian H, Wetherill LF, Dick DM, Almasy L, Bierut L, Bucholz KK, Goate A, Hesselbrock V, Kuperman S, Nurnberger J, Porjesz B, Rice J, Schuckit M, Tischfield J, Begleiter H, Foroud T. Association of alcohol dehydrogenase genes with alcohol dependence: a comprehensive analysis. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(9):1539–1549. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G. The Alcohol Dependence Syndrome: a concept as stimulus to enquiry. Br J Addiction. 1986;81:171–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1986.tb00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Gross MM. Alcohol dependence: provisional description of a clinical syndrome. BMJ. 1976;1:1058–1061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6017.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF. Barriers to alcoholism treatment: reasons for not seeking treatment in a general population sample. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58(4):365–371. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, Chou PS, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;39:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01134-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Moore TC, Shepard J, Kaplan K. Source and Accuracy Statement: Wave 1 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) [May 29, 2008];2003a Available at: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov.

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003b;20:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP. Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004a;65(7):948–958. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RP, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004b;61(8):807–16. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Compton WM, Crowley TJ, Hasin DS, Helzer JE, Li TK, Rounsaville BJ, Volkow ND, Woody GE. Errors in assessing DSM-IV substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007a;64(3):379–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.379. author reply 381-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Harford TC, Muthén BO, Yi HY, Hasin DS, Stinson FS. DSM-IV alcohol dependence and abuse: further evidence of validity in the general population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007b;86(2-3):154–166. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Kerr WC. Alcohol measurement methodology in epidemiology: recent advances and opportunities. Addiction. 2008;103:1982–1099. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02197.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guze SB, Wolfgram ED, McKinney JK, Cantwell DP. Psychiatric illness in families of convicted felons: a study of 519 first-degree relatives. Dis Nerv Syst. 1967;28:651–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna EZ, Chou SP, Grant BF. The relationship between drinking and heart disease morbidity in the United States: results from the National Health Interview Survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:111–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Grant BF. The co-occurrence of DSM-IV alcohol abuse in DSM-IV alcohol dependence: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions on heterogeneity that differ by population subgroup. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(9):891–896. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Paykin A. Alcohol dependence and abuse diagnoses: concurrent validity in a nationally representative sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23:144–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Grant B, Endicott J. The natural history of alcohol abuse; implications for definitions of alcohol use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1537–1541. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.11.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Carpenter KM, McCloud S, Smith M, Grant BF. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a clinical sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997a;44:133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Van Rossem R, Endicott J. Differentiating DSM-IV alcohol dependence and abuse by course: community heavy drinkers. J Substance Abuse. 1997b;9:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Grant BF, Cottler L, Blaine J, Towle L, Ustün B, Sartorius N. Nosological comparisons of alcohol and drug diagnoses: a multisite, multi-instrument international study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997c;47(3):217–226. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Carpenter KM, Paykin A. At-risk drinkers in the household and short-term course of alcohol dependence. J Stud Alcohol. 1999a;60(6):769–775. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Paykin A, Endicott J, Grant B. The validity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse: drunk drivers versus all others. J Stud Alcohol. 1999b;60(6):746–755. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Aharonovich E, Liu X, Maman Z, Matseoane K, Carr LG, Li TK. Alcohol dependence symptoms and alcohol dehydrogenase 2 polymorphism: Israeli Ashkenazis, Sephardics, and recent Russian immigrants. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26(9):1315–1321. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000029597.07916.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Schuckit MA, Martin CS, Grant BF, Bucholz KK, Helzer JE. The validity of DSM-IV alcohol dependence: what do we know and what do we need to know? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:244–252. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000060878.61384.ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Hatzenbuehler M, Keyes KM, Ogburn E. Substance Use Disorders: DSM-IV and ICD-10. Addiction. 2006;101(Supple):59–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Narrow WE, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Racial/ethnic disparities in service utilization for individuals with co-occuring mental health and substance use disorders in the general population: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(7):1112–1121. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, van den Brink W, Guth SE. Should there be both categorical and dimensional criteria for the substance disorders in DSM-IV? Addiction. 2006;101:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, Bucholz KK, Gossop M. A dimensional option for the diagnosis of substance dependence in DSM-V. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2007;16:24–33. doi: 10.1002/mpr.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindmarch I, Kerr JS, Sherwood N. The effects of alcohol and other drugs on psychomotor performance and cognitive function. Alcohol Alcohol. 1991;26:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman CDJ, English DR, Milne E, Winter MG. Meta-analysis of alcohol and all-cause mortality: A validation of NHMRC recommendations. Med J Aust. 1996;164:141–145. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb122011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommer DW, Momenan R, Kaiser E, Rawlings RR. Evidence for a gender-related effect of alcoholism on brain volumes. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:198–204. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley TD, Edenberg TJ, Li TK. In: The Pharmacogenomics of alcoholism, in Pharmacogenomics: The Search for Individualized Therapeutics. Licinio J, Wong ML, editors. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR. A Rasch model analysis of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence items in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1165–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key J, Hodgson S, Omar RZ, Jensen TK, Thompson SG, Boobis AR, Davies DS, Elliott P. Meta-analysis of studies of alcohol and breast cancer with consideration of the methodological issues. Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17(6):759–770. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008a;93(1-2):21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, Alberti P, Narrow WE, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Service utilization differences for axis I psychiatric and substance use disorders between white and black adults. Psychiatr Serv. 2008b;59(8):893–901. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.8.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(11):858–866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Nichol PE, Hicks BM, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG, McGue M. Using Latent Trait Modeling to Conceptualize an Alcohol Problems Continuum. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16(2):107–119. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang I, Guralnik J, Wallace RB, Melzer D. What level of alcohol consumption is hazardous for older people? Functioning and mortality in U.S. and English national cohorts. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(1):49–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TK. Pharmacogenetics of responses to alcohol and genes that influence alcohol drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61(1):5–12. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TK, Yin SJ, Crabb DW, O'Conner S, Ramchandani VA. Genetic and environmental influences on alcohol metabolism in humans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:136–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TK, Hewitt BG, Grant BF. The Alcohol Dependence Syndrome, 30 years later: a commentary. Addiction. 2007a;102(10):1522–1530. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TK, Hewitt BG, Grant BF. Is there a future for quantifying drinking in the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of alcohol use disorders? Alcohol Alcohol. 2007b;42:57–63. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Kranzler H, Zuo L, Yang B, Lappalainen J, Gelernter J. ADH4 gene variation is associated with alcohol and drug dependence: results from family controlled and population-structured association studies. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15(11):755–768. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000180141.77036.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Kranzler HR, Zuo L, Wang S, Schork NJ, Gelernter J. Diplotype trend regression analysis of the ADH gene cluster and the ALDH2 gene: multiple significant associations with alcohol dependence. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78(6):973–987. doi: 10.1086/504113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Chung T, Kirisci L, Langenbucher JW. Item Response Theory Analysis of Diagnostic Criteria for Alcohol and Cannabis Use Disorders in Adolescents: Implications for DSM-V. J Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115(4):807–814. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Tam T, Greenfield TK, Caetano R. Risk functions for alcohol-related problems in a 1988 U.S. national sample. Addiction. 1996;91:1427–1437. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.911014273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MY, Sherlock S. Sex-related differences among 100 patients with alcoholic liver disease. Br Med J. 1977;1:939–941. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6066.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HB, Chen CM, Yi H. DSM-IV Criteria Endorsement Patterns in Alcohol Dependence: Relationship to Severity. ACER. 2008;32:2. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Task Force Report on Binge Drinking. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician's Guide. [August 29, 2007];2005 Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/guide.pdf.

- Nelson CB, Rehm J, Ustun B, Grant BF, Chatterji S. Factor structure of DSM-IV substance disorder criteria endorsed by alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and opiate users: results from the World Health Organization Reliability and Validity Study. Addiction. 1999;94(6):843–855. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9468438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot H, Baillie AJ, Teesson M. The structure of alcohol dependence in the community. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pull CB, Saunders JB, Mavreas V, Cottler LB, Grant BF, Hasin DS, Blaine J, Mager D, Ustun BT. Concordance between ICD-10 alcohol and drug use disorder criteria and diagnoses as measured by the AUDADIS-ADR, CIDI and SCAN: results of a cross-national study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47(3):207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Greenfiled TK, Walsh G, Xie X, Robson L, Single E. Assessment methods for alcohol consumption, prevalence of high risk drinking and harm: a sensitivity analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:219–224. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Monga N, Adlaf E, Taylor B, Bondy SJ, Fallu JS. School matters: drinking dimensions and their effects on alcohol-related problems among Ontario school students. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40:569–574. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Triangle Institute. Software for Survey Data Analysis (SUDAAN), Version 9.1. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Room R. Stigma, social inequality and alcohol and drug use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2004;24(2):143–155. doi: 10.1080/09595230500102434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Smith SM, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Dawson DA, Huang B, Stinson FS, Grant BF. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92(1-3):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M, Light JM, Gruenewald PJ. Alcohol consumption and problems. The relevance of drinking patterns. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:921–930. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128238.62063.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha TD, Chou PS, Grant BF. Toward an alcohol use disorder continuum using item response theory: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:931–941. doi: 10.1017/S003329170600746X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha TD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. The role of alcohol consumption in future classifications of alcohol use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweinsburg BC, Alhassoon OM, Taylor MJ, Gonzalez R, Videen JS, Brown GG, Patterson TL, Grant I. Effects of alcoholism and gender on brain metabolism. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1180–1183. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Bond J. Ethnic disparities in clinical severity and services for alcohol problems: results from the National Alcohol Survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(1):48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea S, Wall T, Carr L, Li T. ADH2 and alcohol-related phenotypes in Ashkenazic Jewish American college students. Behav Genet. 2001;31(2):231–239. doi: 10.1023/a:1010261713092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, Yaun SS, van den Brandt PA, Folsom AR, Goldbohm RA, Graham S, Holmberg L, Howe GR, Marshall JR, Miller AB, Potter JD, Speizer FE, WIllitt WC, Wolk A, Hunter DJ. Alcohol and breast cancer: A pooled analysis of cohort studies. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;279:535–540. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.7.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell T, Donath S, Cooper-Stanbury M, Chikritzhs T, Catalano P, Mateo C. Under-reporting of alcohol consumption in household surveys: a comparison of quantity-frequency, graduated-frequency and recent recall. Addiction. 2004;99:1024–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbano-Marquez A, Estruch R, Fernandez-Sola J, Nicolas JM, Pare JC, Rubin E. The greater risk of alcoholic cardiomyopathy in women compared to men. JAMA. 1995;274:149–154. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530020067034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ustun B, Compton W, Mager D, Babor T, Baiyewu O, Chatterji S, Cottler L, Gogus A, Mavreas V, Peters L, Pull C, Saunders J, Smeets R, Stipec MR, Vrasti R, Hasin D, Room R, Van den Brink W, Regier D, Blaine J, Grant BF, Sartorius N. WHO Study on the reliability and validity of the alcohol and drug use disorder instruments: overview of methods and results. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47(3):161–170. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrasti R, Grant BF, Chatterji S, Ustun BT, Mager T, Olteanu I, Badoi M. Reliability of the Romanian version of the alcohol module of the WHO Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule–Alcohol/Drug-Revised. Eur Addict Res. 1998;4(4):144–149. doi: 10.1159/000018947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Nelson TF. Relationship between levels of consumption and harms in assessing drink cut points for alcohol research: commentary on “many college freshmen drinking at levels far beyond the binge threshold: by White et al. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:922–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]