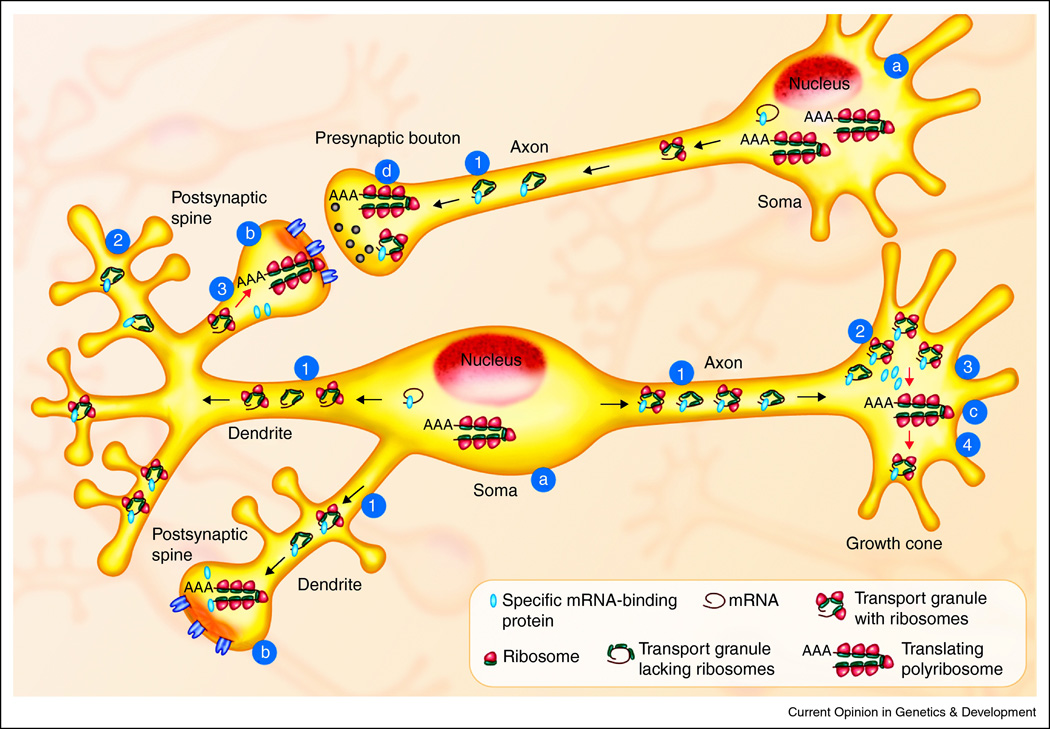

Figure 1. Points of Translational Regulation in Neurons.

Neuronal networks (light blue) have a greater need for spatial and temporal control of translation than many other cell types because of their architecture and need to rapidly alter protein synthesis in response to signals. While the soma was originally believed to be the site of all protein synthesis in the neuron (a) it is now clear that actively translating polyribosomes are present in and near the dendritic spines (the sites of postsynaptic excitatory input, b), in growth cones during development and regeneration after injury (c) and likely on the presynaptic side of synapses as well (d). Localized protein synthesis permits rapid changes in the local proteome at sites distant from the soma but requires delivery of the mRNA templates (black spirals) and synthetic machinery to these sites in the form of transport granules with or without ribosomes (40S and 60S subunits are yellow and blue dots, respectively). The prevailing theory is that specific mRNA-binding proteins (red dots) repress translation during transport (1) and maintain the mRNA in a repressed state until new protein synthesis is needed (2). Mechanisms exist to activate the synthesis of specific proteins in the dendrites and growth cones (3) and finally, specific mechanisms halt their translation as well (4).