Abstract

The endoderm in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans is clonally derived from the E founder cell. We identified a single genomic region (the endoderm-determining region, or EDR) that is required for the production of the entire C. elegans endoderm. In embryos lacking the EDR, the E cell gives rise to ectoderm and mesoderm instead of endoderm and appears to adopt the fate of its cousin, the C founder cell. end-1, a gene from the EDR, restores endoderm production in EDR deficiency homozygotes. end-1 transcripts are first detectable specifically in the E cell, consistent with a direct role for end-1 in endoderm development. The END-1 protein is an apparent zinc finger-containing GATA transcription factor. As GATA factors have been implicated in endoderm development in other animals, our findings suggest that endoderm may be specified by molecularly conserved mechanisms in triploblastic animals. We propose that end-1, the first zygotic gene known to be involved in the specification of germ layer and founder cell identity in C. elegans, may link maternal genes that regulate the establishment of the endoderm to downstream genes responsible for endoderm differentiation.

Keywords: GATA transcription factor, endoderm, germ layer, deficiencies, Wnt signaling, C. elegans development

Early in embryonic development of all triploblastic animals, cells undergo dramatic rearrangements to form three germ layers. The mechanisms that establish the germ layers and that direct their unique pathways of differentiation are central concerns in animal embryology. The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans provides an amenable molecular genetic system with which to study the mechanisms that specify the germ layers. The relatively simple pattern of development of the C. elegans endoderm, which gives rise to a single organ, the intestine, has made it the focus of a number of embryological, genetic, and molecular studies (e.g., Laufer et al. 1980; Edgar and McGhee 1988; Aamodt et al. 1991; Goldstein 1992).

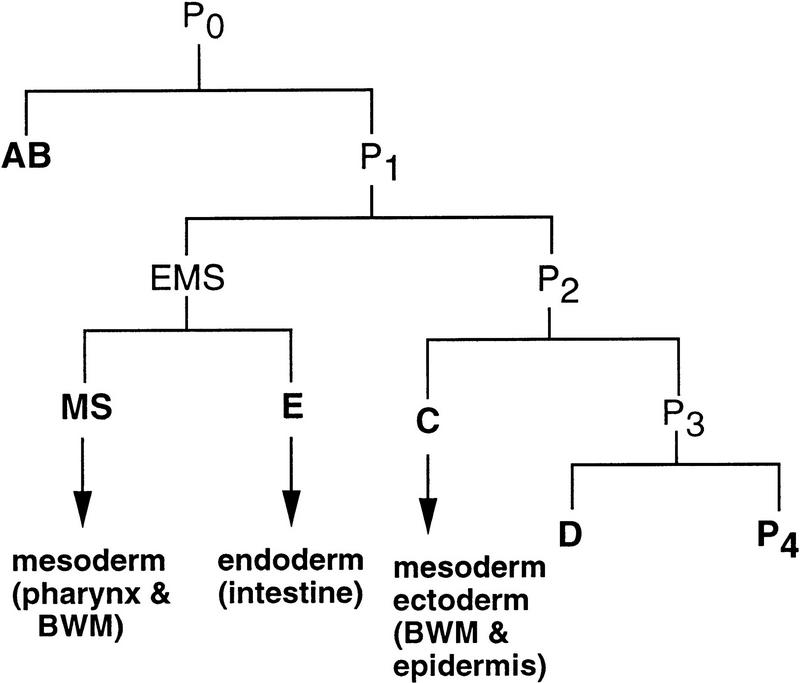

The endoderm in nematodes arises exclusively from the E blastomere, one of the six “founder” cells (Fig. 1; Deppe et al. 1978; Sulston et al. 1983). Each of the founder cells shows distinct rates of cell division and produces a unique repertoire of differentiated cell types. The ability to make endoderm appears to be restricted to the E blastomere by a series of asymmetric cell divisions that yield qualitatively different sister cells (Laufer et al. 1980; Cowan and McIntosh 1985; Schierenberg and Wood 1985; Edgar and McGhee 1986). These observations suggested that the fate of E is controlled in part by regulatory factors that act cell autonomously. However, specification of the endoderm has also been shown to require an inductive cellular interaction: EMS, the parent of E and the MS founder cell, a mesodermal progenitor, is induced to undergo a developmentally asymmetric cell division by a neighboring cell, P2 (Goldstein 1992, 1993). This interaction was recently found (Rocheleau et al. 1997; Thorpe et al. 1997) to involve the Wnt signaling pathway (for review, see Nusse and Varmus 1992). If this interaction is prevented, EMS divides to produce two equivalent MS-like cells and no intestine is generated (Goldstein 1992, 1993).

Figure 1.

Origin of the E blastomere and the intestine. The diagram shows the early lineage and the six founder cells (labeled in boldface type) of the C. elegans embryo. The germ layers and major cell types produced by E, MS, and C during wild-type development are indicated by arrows. (BWM) Body-wall muscle. For a complete description of the embryonic lineages and cell fates, see Sulston et al. (1983).

Several maternal genes have been identified that are required for proper endoderm formation; however, none of these appears to direct the fate of the E blastomere specifically (e.g., Kemphues et al. 1988; Bowerman et al. 1992; Mello et al. 1992; Lin et al. 1995). For example, although mutations in par-1 prevent endoderm formation, this gene appears to be required principally for establishing the initial anterior–posterior asymmetry of the early embryo (Kemphues et al. 1988). Mutations in the skn-1 gene affect the development of both E and MS, causing these blastomeres to develop like their cousin, C, and produce body-wall muscle and epidermis (Bowerman et al. 1992). skn-1 encodes an apparent transcription factor that accumulates in EMS and its descendants through the 12-cell stage, suggesting that SKN-1 may activate early zygotic transcription of genes that control E- and MS-specific differentiation (Bowerman et al. 1993; Blackwell et al. 1994). The pie-1 and pop-1 maternal genes appear to prevent blastomeres other than E from producing endoderm (Mello et al. 1992; Lin et al. 1995). pie-1 encodes an apparent zinc finger protein (Mello et al. 1996) that prevents the sister of EMS from adopting an EMS-like fate (Mello et al. 1992) by causing general repression of zygotic gene expression in that cell (Mello et al. 1996; Seydoux et al. 1996). In pop-1 mutant embryos, MS adopts the fate of its sister, E, and makes endoderm instead of mesoderm (Lin et al. 1995). The POP-1 protein is a putative DNA-binding protein containing a high mobility group (HMG) box motif related to LEF-1 (Travis et al. 1991; Lin et al. 1995). POP-1 is present at higher levels in MS than in E, and it has been implicated recently as a component in the Wnt pathway involved in induction of endoderm by P2 (Rocheleau et al. 1997; Thorpe et al. 1997). POP-1 may make MS different from E by repressing transcription of zygotic genes that promote endoderm formation. Zygotically required genes that direct endoderm formation and that might be targets of POP-1 and SKN-1 have not been reported previously.

We describe here the characterization of a genomic region, the endoderm-determining region (EDR), that is required zygotically to specify the E fate in C. elegans. Embryos homozygous for deletions of the EDR do not produce endoderm because the E blastomere adopts a fate similar to that of its cousin, C, thereby producing ectoderm and mesoderm. We identified a gene, end-1, in the EDR based on its ability to restore endoderm differentiation in the deficiency mutant embryos. end-1 encodes a GATA transcription factor-like protein containing a single zinc finger domain. Similar factors have been shown to be expressed in the endoderm of vertebrates and the SERPENT/ABF GATA factor has recently been found to be required for endoderm production in Drosophila (Reuter 1994; Rehorn et al. 1996). We propose that END-1 regulates the identity of the E blastomere and participates in specifying the endoderm by a mechanism that is phylogenetically conserved. end-1 transcripts are first present in the E cell. This early expression pattern and the phenotype of EDR deficiency mutants suggest that end-1 may be a direct downstream target of the maternal Wnt signaling pathway that controls the identity of the E blastomere in C. elegans embryos.

Results

Identification of a genomic region required for production of the endoderm

The precursor of the endoderm, E, arises at the seven-cell stage. Its daughters migrate into the interior of the embryo at the onset of gastrulation in the 28-cell-stage embryo and undergo several rounds of division to produce the 20 differentiated intestinal cells by mid-embryogenesis. To identify zygotically (embryonically transcribed) genes required for endoderm formation, we systematically scanned a set of deficiencies that collectively remove ∼67%–80% of the C. elegans genome (see also Terns et al. 1997). A single region on chromosome V, the EDR, was identified that is required for intestinal differentiation (see below).

To isolate point mutations that result in a penetrant absence of intestine, several large-scale, genome-wide screens of zygotic lethal mutants were performed in two laboratories (J. Rothman and J. Priess, unpubl.). Although a point mutagen was used, these screens identified only three deficiency mutants (wDf3, wDf4, and zuDf2), all of which reside in the vicinity of the EDR. An additional screen of ∼17,000 haploid genomes targeted to the EDR also failed to identify any point mutations that result in the penetrant absence of intestine. These observations suggest that the EDR may contain functionally redundant genes required for production of a differentiated intestine (see Discussion).

The failure to isolate point mutations led us to characterize the requirement of the EDR by analyzing the phenotypes of deficiency homozygotes. Embryos homozygous for zuDf2, itDf2, nDf42, wDf3, and wDf4, which delete the EDR (for details, see Fig. 6A, below), completely lack gut-specific birefringent rhabditin granules (Fig. 2) and fail to express two gut-specific molecular markers (Fig. 3). As other major differentiated tissue types, including pharynx muscle, body-wall muscle, epidermis, and neurons, are made in zuDf2 mutant embryos (Fig. 3), this differentiation defect appears to be specific to endoderm.

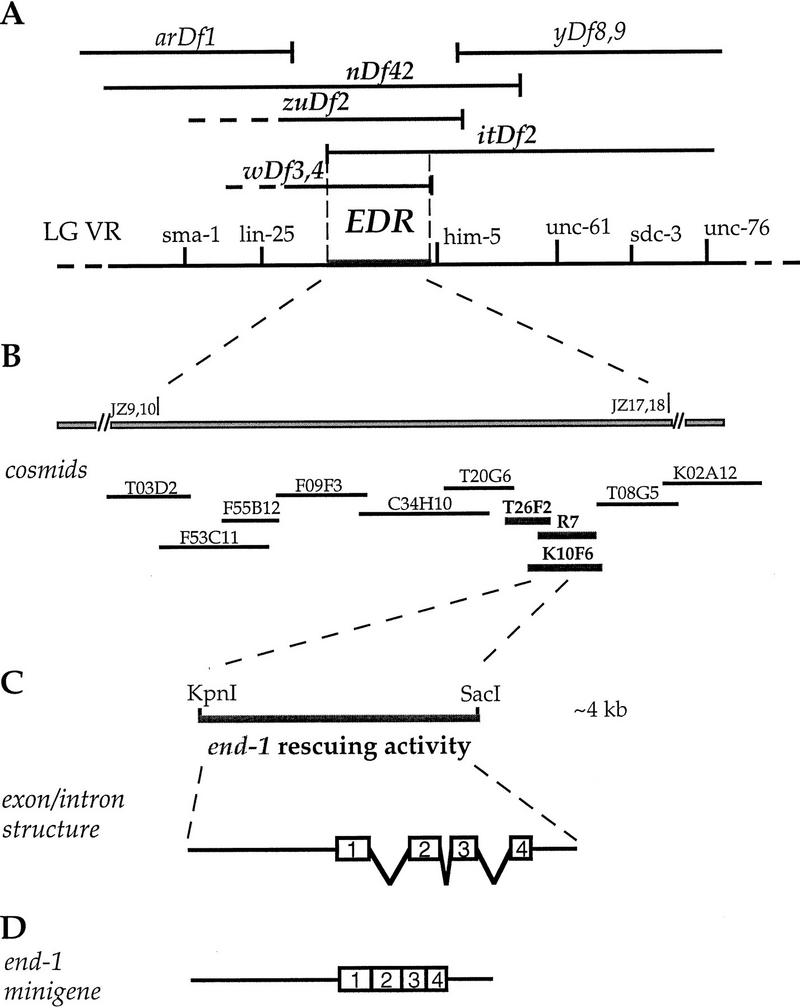

Figure 6.

Genetic and molecular identification of the end-1 region and the end-1 gene. (A) Genetic map of a portion of the right arm of linkage group (chromosome) V and several deficiencies in the region. The region required for endoderm specification, henceforth called the “EDR,” was delimited by mapping the endpoints of the overlapping deficiencies on the physical map and comparing their intestine differentiation phenotypes. arDf1, yDf8, and yDf9 homozygotes make intestine, whereas nDf42, zuDf2, itDf2, wDf3, and wDf4 homozygotes (labeled in boldface) do not. Based on PCR analysis, itDf2 does not delete sequences including and to the left of the JZ 9,10 primers, which are derived from cm01h10, a cDNA sequence available from ACeDB. wDf4 complements him-5, which is contained in cosmid K02A12, but deletes the sequence amplified by the JZ 17,18 primers, which are derived from the org-1 sequence on the cosmid T08G5. The genomic region required for endoderm specification, which is shown by broken lines, is therefore defined by the left endpoint of itDf2 and the right endpoint of wDf4. We estimate that the interval of the end-1 region is <200 kb. (B) Cosmid clones in the end-1 region. A subset of cosmids in the area was used in the transformation rescue experiments, and three overlapping cosmids (labeled in boldface), K10F6, R7, and T26F2, were found to carry rescuing activity. (C) The location of end-1 was further refined by testing whether subclones derived from K10F6 contained rescuing activity. The ∼4-kb KpnI–SacI genomic fragment indicated by a thicker line was found to be the minimum fragment containing rescuing activity. (□) Exons as deduced by comparing the sequence of the 4-kb rescuing fragment and the nearly full-length 0.85-kb cDNA. (D) The end-1 minigene insert. The insert contains an ∼1.8-kb end-1 upstream genomic sequence and the end-1 cDNA and end-1 3′-untranslated region (UTR) sequences.

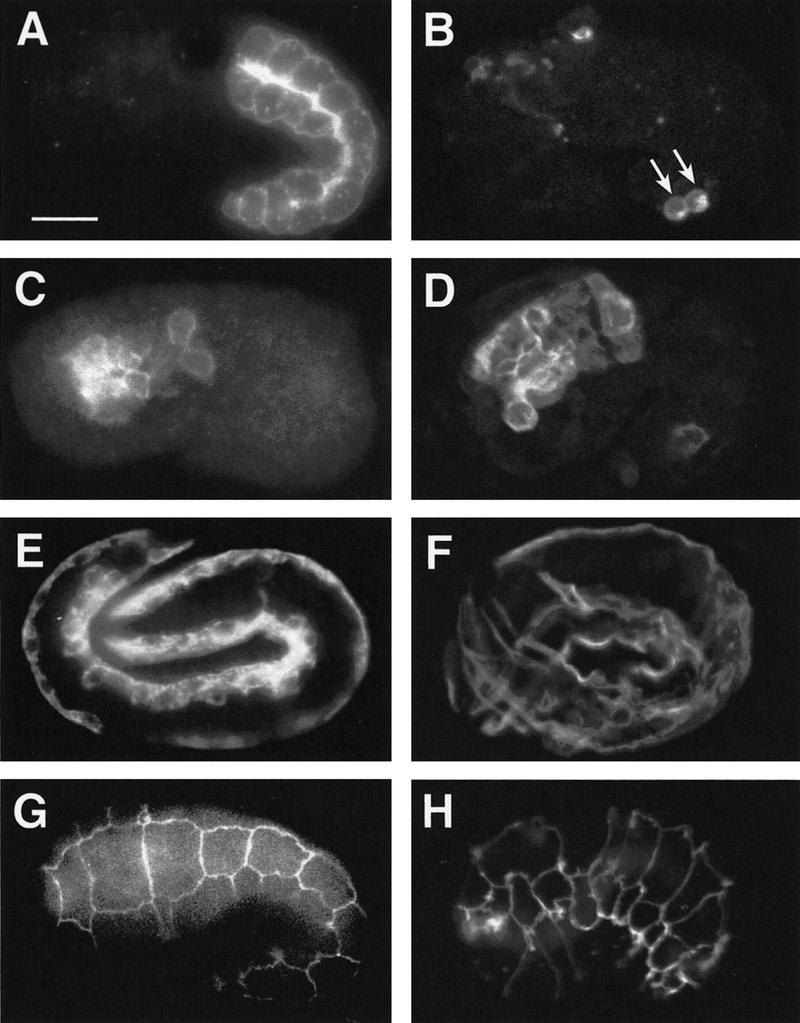

Figure 2.

Absence of a differentiated intestine in a terminally arrested zuDf2 homozygous embryo. Shown are micrographs of live embryos viewed under Nomarski optics (A,B) or dark field with polarized light (C,D). A wild-type embryo at an early stage in morphogenesis (1.5-fold) is shown in A and C. A terminally arrested homozygous zuDf2 embryo is shown in B and D. When viewed by Nomarski microscopy, intestinal cells containing large nuclei with a prominent nucleolus (arrowhead) are evident in the wild-type embryo (A) but not in the mutant (B). The pharynx primordium (arrow) is visible in both wild-type and homozygous zuDf2 embryos. Although birefringent granules characteristic of a differentiated intestine are obvious under polarized light in wild type (C), they are absent in the homozygous zuDf2 embryo (D). Similar observations were made in itDf2 homozygous embryos. Other intestinal differentiation markers, including a gut esterase (Edgar and McGhee 1986), were also found to be absent in itDf2 homozygous embryos (not shown). Anterior is to the left and dorsal is to the top in each panel. Bar, ∼10 μm.

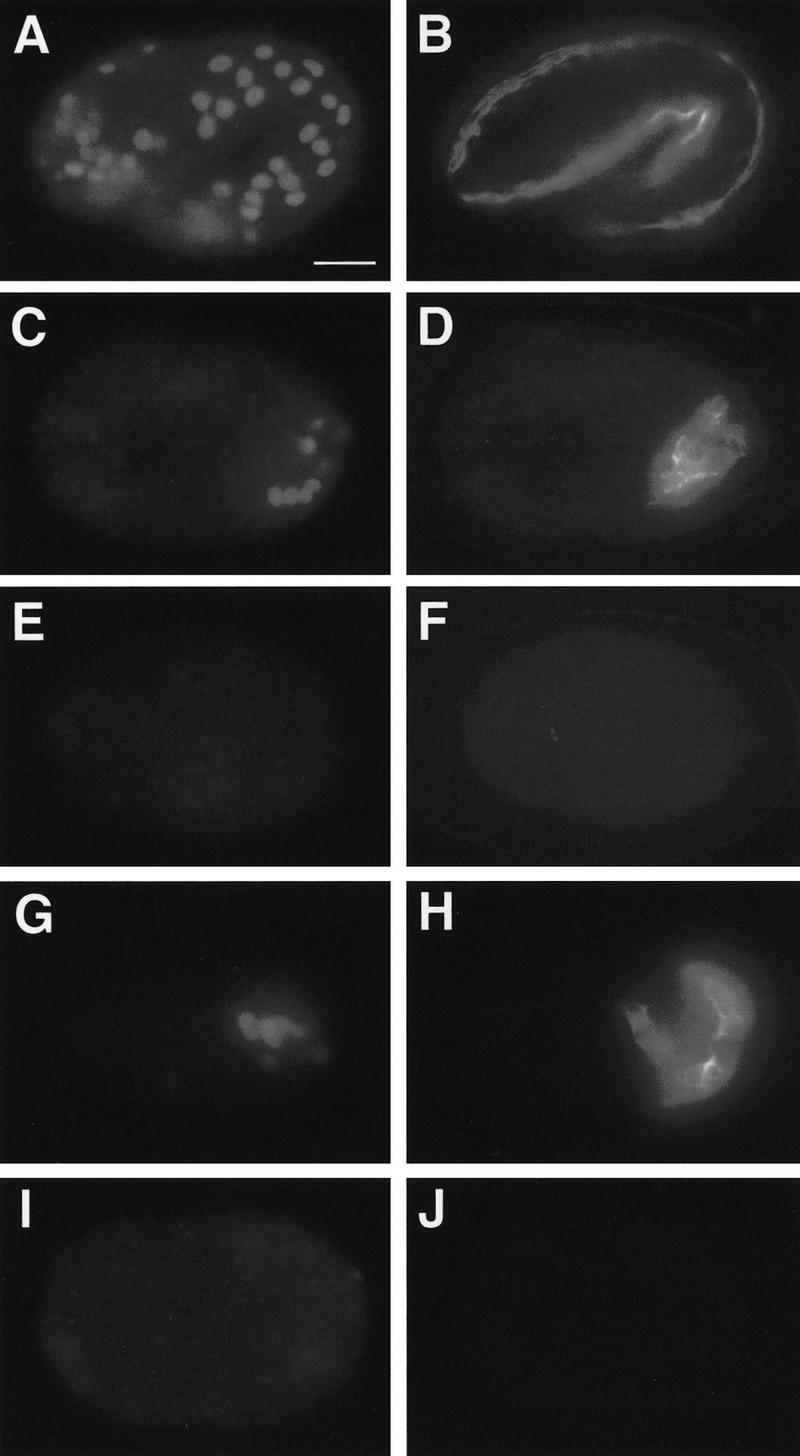

Figure 3.

Tissue differentiation in wild-type and zuDf2 mutant embryos. Immunofluorescence analysis of tissue differentiation in partially elongated (1.5-fold) wild-type (A,C,G), elongated (pretzel stage) wild-type (E), and terminal homozygous zuDf2 (B,D,F,H) embryos. (A,B) Embryos stained with mAb 1CB4, which reacts with the 20 embryonic intestinal cells (Okamoto and Thomson 1985) and the intestinal–rectal valve cells. The intestinal cells are absent in homozygous zuDf2 embryos although the two intestinal–rectal valve cells, which arise from a nonendodermal precursor (the AB founder cell) are present (arrows). (C,D) Embryos stained with 3NB12, a monoclonal antibody that recognizes a subset of pharynx muscles (Priess and Thomson 1987). (E,F) Embryos stained with NE8/4C6, a monoclonal antibody that recognizes body-wall muscle cells (Goh and Bogaert 1991). (G,H) Surface view of embryos stained with MH27, a monoclonal antibody that recognizes epithelial adherens junctions (Priess and Hirsh 1986); only the epidermal cells are visible in the focal plane shown. Although the nonendodermal tissues are disorganized in terminal zuDf2 embryos, all appear to be made in approximately normal amounts. Large numbers of cells with the characteristic appearance of neurons were also apparent by Nomarski microscopy in zuDf2 and itDf2 embryos (data not shown). Bar, ∼10 μm.

The EDR is required for production of ectopic endoderm in pie-1 and pop-1 mutants

Maternal-effect mutations in pie-1 and pop-1 result in the production of ectopic endoderm as a result of transformations of the P3 and MS blastomeres, respectively, into E-like cells (Mello et al. 1992; Lin et al. 1995). We found that no intestine was made in approximately one-fourth (18 of 65 embryos examined) of the progeny of parents homozygous for pie-1 and heterozygous for itDf2, indicating that production of ectopic intestine in pie-1 mutants requires zygotically expressed genes within the EDR. Moreover, whereas injection of antisense pop-1 RNA into wild-type parents always resulted in a pop-1 phenocopy (all progeny showed extra intestine; n = 226 embryos), approximately one-fourth (46 of 158 embryos examined) of the progeny derived from heterozygous zuDf2 parents injected with the pop-1 antisense RNA completely lacked a differentiated intestine. Together, these observations suggest that the EDR is essential for a blastomere to produce endoderm irrespective of the position or lineal origin of the blastomere.

E is transformed to a C-like blastomere in EDR deficiency embryos

To address whether the E cell is mis-specified in EDR deficiency embryos, we asked what differentiated tissue types are generated from E when it is isolated by laser ablation of all other cells (Fig. 4; Table 1). Whereas E blastomeres isolated from wild-type embryos always produce intestinal cells, one-fourth of the E blastomeres isolated from embryos produced by zuDf2 heterozygotes generated differentiated body-wall muscle and epidermis (Table 1; Fig. 4), cell types characteristic of the C blastomere (Fig. 1).

Figure 4.

The intestinal precursor E produces epidermis and body-wall muscle in zuDf2 mutants. Each row shows a single embryo stained with rabbit anti-LIN-26 (left), which recognizes the nuclei of epidermal cells, and with mAb 5.6 (right), which recognizes the cytoplasm of body-wall muscle. (A,B) An intact wild-type embryo at the two-fold stage produces epidermis (A) and body-wall muscle (B). (C–J) Partial embryos were produced by ablating all founder cells except the C blastomere (“C” isolation) (C,D) or the E blastomere (E–J) in either wild-type (C–F) or F1 embryos from a strain heterozygous for zuDf2 (G–J). An isolated wild-type C blastomere produces both epidermis (C) and body-wall muscle (D), whereas an isolated wild-type E blastomere produces neither epidermis (E) nor body-wall muscle (F). E isolations from zuDf2 heterozygotes produce two classes. Approximately one in four do not produce gut but instead produce epidermis (G) and body-wall muscle (H); these are putative zuDf2 homozygotes. Approximately three in four produce intestine but fail to produce epidermis (I) and body-wall muscle (J). Embryos shown in C–J are representative individuals used to generate data in Table 1. Bar, ∼10 μm.

Table 1.

Cell fate transformation of E blastomeres

| Strain and genotype

|

Total no. of E isolations

|

Embryos with intestineb

|

Embryos with no intestinec

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| epidermis

|

body-wall muscle

|

epidermis

|

body-wall muscle

|

||

| JJ1035 | |||||

| zuDf2/sqt-3(sc63) egl-1(n986) unc-76(e911) | 29 | 0/23 | 0/23 | 5/6d | 6/6 |

| MT2560a | |||||

| sqt-3(sc63) egl-1(n986) unc-76(e911) | 25 | 0/25 | 0/25 | 0/0 | 0/0 |

Intestinal and epidermal or muscle differentiation was scored in embryos after killing early blastomeres except E with a laser microbeam (see Materials and Methods). The differentiation of intestine was scored by observing gut granules or staining with mAb 1CB4. The differentiation of epidermis was scored by staining with anti-LIN-26; body-wall muscle was scored by staining with mAb 5.6.

MT2560 is the strain isolated from JJ1035. It serves as a control.

Embryos positive or

negative for gut granules were further stained with anti-LIN-26 and mAb 5.6.

One out of six embryos was negative for anti-LIN-26 immunostaining. This embryo appears to be damaged during the ablation.

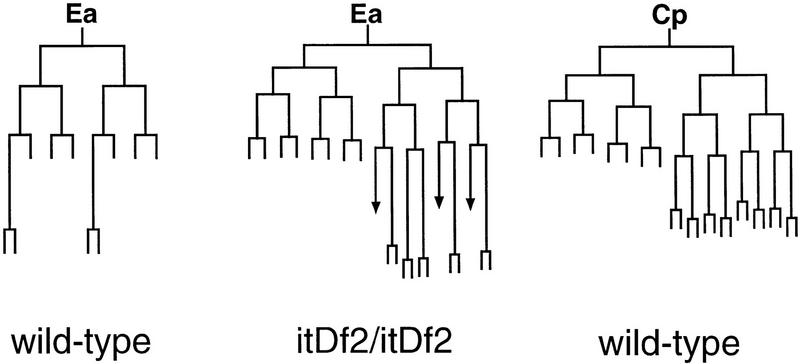

We performed cell lineage analysis of itDf2 mutant embryos to ask whether E is transformed to a C-like cell. The earliest detectable lineage alteration was the premature division and defective gastrulation of the E daughters (see Table 2). Gastrulation begins at the 28-cell stage in wild-type embryos, when the E daughters migrate into the interior (Sulston et al. 1983). In five itDf2 homozygotes, the E daughters divided precociously on the surface of the embryo; in some cases the E granddaughters later migrated inward. Analysis of the later E-lineage pattern in two itDf2 mutant embryos showed that it was dramatically altered and strongly resembled the lineage of the wild-type C founder cell (Fig. 5). Limited lineage analysis of other blastomeres, for example, C and MS, revealed apparently normal lineages arising from these cells (not shown).

Table 2.

Decrease in cell cycle length of E2 cells in EDR deficiency embryos

| Genotype of embryo

|

E | | Ea | | Relative timing of Ea → Eal + Ear division compared to wild type

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| | Ea

|

| Ep

|

| Eal

|

| Ear

|

||

| Wild type | 24 min (n = 19) | 49 min (n = 19) | 1 | ||

| itDf2/itDf2 | 24 min (n = 2) | 39 min (n = 2) | 0.8 | ||

| Rescued itDf2/itDf2 | 24 min (n = 3) | 43 min (n = 3) | 0.9 | ||

Embryos from wild type, JR70 (ced-1; itDf2/unc-42 dpy-21), and the isogenic strain JR194 [wEx43; rol-6 (su1006) :: end-1(+)] hermaphrodites were collected and used in lineage analysis (see Materials and Methods). All recordings were performed at 20 ± 2°C. Terminally arrested embryos from JR194 that contained gut granules were considered rescued mutants.

Figure 5.

The E lineage is altered in homozygous itDf2 embryos. The Ea branch of the E lineage in wild-type (left) and itDf2 embryos (middle) is shown. The Ea lineage of the mutant is dramatically different from the wild-type Ea lineage (left) and most closely resembles the wild-type lineage of Ca and Cp (Although the wild-type Ca and Cp lineages are similar, the Cp lineage, which most closely resembles the mutant lineage, is shown here at right). Termination of a vertical line indicates that the cell did not divide for at least 200 min after its birth. The arrows in the mutant lineage indicate cells that were lost during the lineage tracing. The cells derived from E in the itDf2 mutant divide at a faster rate than normal and give rise to extra divisions (see text). Similar observations were made in one other homozygous itDf2 embryo (not shown). Portions of the MS and C lineages were also followed in the itDf2 mutant embryos and appeared normal. Wild-type lineages are taken from Sulston et al. (1983). The timings of cell division in the mutant embryo were normalized to that of wild type.

These results strongly suggest that the failure to make intestine in EDR deficiency mutants results from a transformation of the E cell into a C-like cell. Thus, the EDR apparently contains one or more zygotic genes required to direct the production of endoderm from the E cell.

Molecular identification of the end-1 gene

To determine the physical extent of the EDR, we mapped the endpoints of overlapping deficiencies (summarized in Fig. 6; see Materials and Methods) and narrowed the maximum interval required for production of intestine to <200 kb. Clones in the interval were tested for rescue of the intestinal differentiation defect by transformation into deficiency heterozygotes (see Materials and Methods). A 4-kb fragment apparently containing a single gene, end-1 (for endoderm specification), was found to be sufficient to rescue the intestinal differentiation defect (see below) but not the embryonic lethality of the deficiencies, which remove many genes.

Rescued itDf2 embryos appeared virtually identical to untransformed itDf2 embryos except for the presence of differentiated intestinal cells (Fig. 7). In addition, the E-cell lineage in rescued embryos was found to be similar to the wild-type E lineage (Fig. 8). Premature division of the E daughters was partially rescued in transgenic deficiency homozygotes carrying extrachromosomal copies of end-1(+) (Table 2). Gastrulation appeared to have occurred, based on the organization and position of the intestine in rescued embryos (Fig. 7A). These results indicate that end-1(+) activity can direct E-cell specification in EDR deficiency embryos.

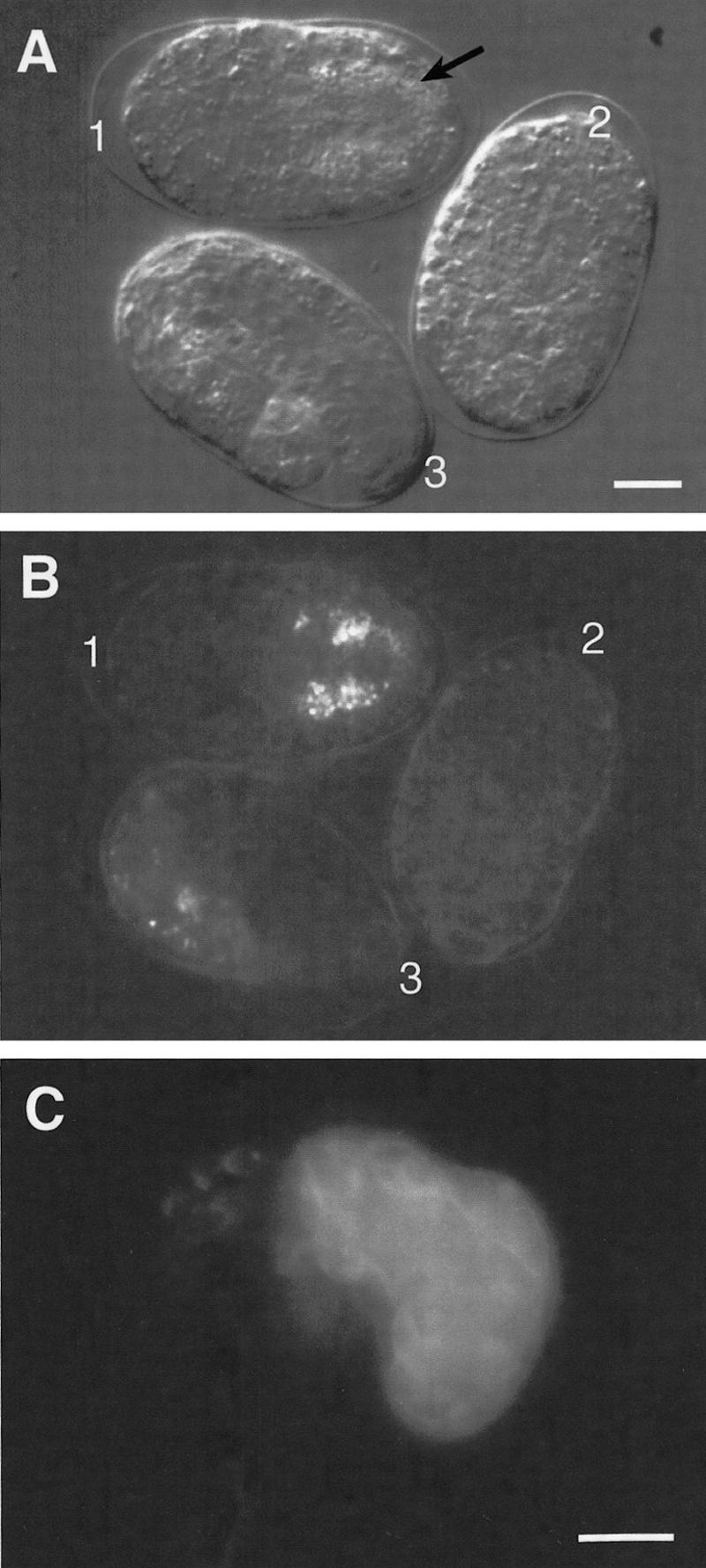

Figure 7.

Intestinal differentiation in rescued homozygous itDf2 embryos carrying the end-1 gene. Three two- or four-cell embryos were collected from heterozygous itDf2 hermaphrodites carrying the end-1 gene on extrachromosomal arrays, mounted on an agar pad, and allowed to develop at 20 ± 2°C. Nomarski (A) and dark-field with polarized light (B) micrographs of these embryos were taken 10 hr after they were mounted. The genotypes of these embryos were inferred 15 hr later based on their terminal morphology and the presence of gut granules seen under polarized light: One hundred percent of itDf2 mutant embryos fail to complete elongation and produced neither intestine nor programmed cell deaths. Thus, embryos with incomplete elongation and no programmed cell deaths but with an intestine are inferred to be itDf2 homozygotes rescued by K10F6, which contains end-1. (B) (1) Rescued homozygous itDf2 mutant; (2) nonrescued homozygous itDf2 mutant; (3) wild-type or heterozygous itDf2 embryo. The intestinal cells have lined up in the middle posterior region of the embryo (a) and show the characteristic appearance of intestinal cells (A, arrow). The normal internal location of the intestinal cells suggests that gastrulation within the E-cell lineage was normal. (C) A terminally arrested homozygous itDf2 embryo bearing extrachromosomal K10F6 and containing gut granules was immunostained with mAb 1CB4, showing that differentiated intestinal cells were made in this embryo. Bar, ∼10 μm. Similar results (not shown) were observed with a subclone containing only the end-1 gene (see description of end-1 minigene construct).

Figure 8.

E-cell lineage in rescued homozygous itDf2 embryos carrying end-1. The first four divisions in the E lineage of a rescued homozygous itDf2 embryo are shown (middle). The E lineages in both a wild-type embryo (left; the genotype was not determined but is either +/+ or Df/+) and an unrescued itDf2 homozygous embryo (right) were also determined for comparison. The development of all three embryos was recorded simultaneously on the same slide. Arrows indicate cells that were lost during the lineage analysis. The E-lineage pattern in the rescued homozygous itDf2 mutant looks similar to a wild-type E lineage. For example, the cell cycle time of E descendants is prolonged such that the E lineage undergoes four rounds of division in the same time that a itDf2 mutant E lineage completes five rounds of division. Similar lineage observations were made with two other rescued itDf2 homozygotes (not shown).

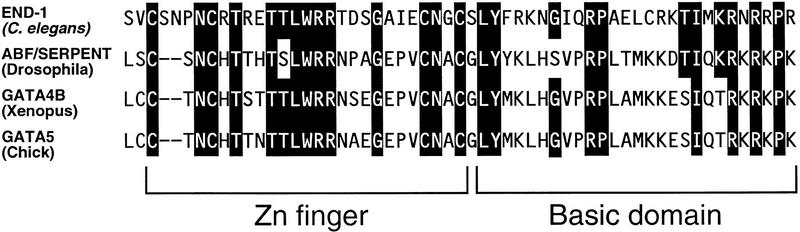

end-1 encodes a GATA factor-like protein

The 4-kb end-1 rescuing fragment was used to isolate several end-1 cDNAs (see Materials and Methods; Fig. 9). The longest (0.85-kb) cDNA detected a single 0.85-kb transcript on a blot of early embryonic mRNA (Fig. 10). Analysis of the end-1 transcript by 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) confirmed that the end-1 cDNA is nearly full length. A minigene containing the 5′ genomic flanking sequence of end-1 placed upstream of the end-1 cDNA (see Fig. 6D) rescued the gut differentiation defect of homozygous deficiency embryos (see Materials and Methods), demonstrating that this cDNA contains the functional end-1 coding region. The 0.85-kb cDNA codes for a 221-amino-acid polypeptide (Fig. 9), a portion of which is an apparent zinc finger domain that shares substantial sequence similarity with the GATA factor family of transcription factors (Fig. 11). As is generally the case with the other GATA factors, the sequences outside the zinc finger and adjacent basic regions are not conserved.

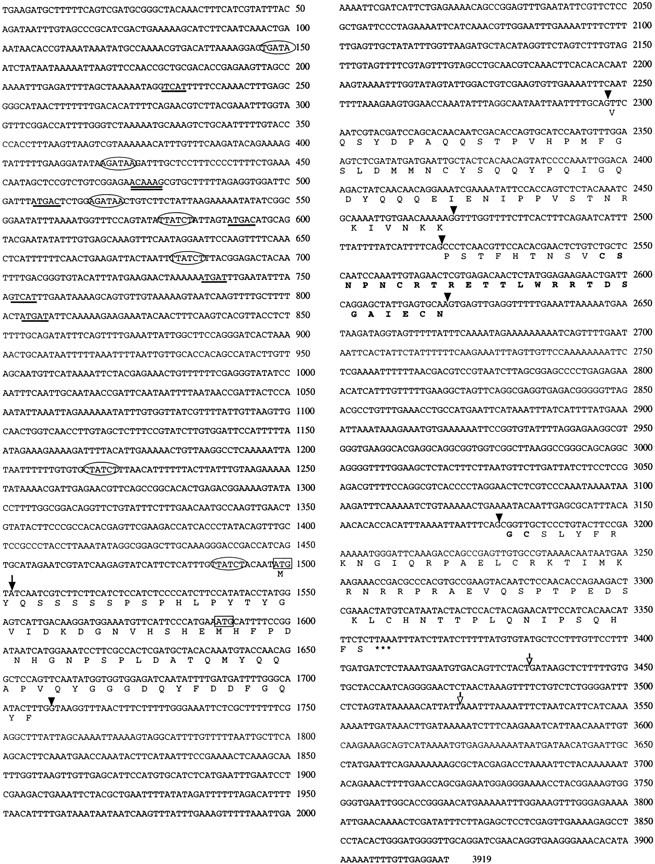

Figure 9.

Sequence of the end-1 gene. Genomic sequence of the region surrounding the end-1 gene is shown, with the predicted protein sequence indicated below. The first nucleotide of the 0.85-kb cDNA clone is indicated by an arrow. The proposed translational start site determined by 5′-RACE is boxed. Another possible in-frame ATG located downstream is also boxed. Splice sites are indicated by arrowheads. The zinc finger region is indicated by boldface letters. The termination codon is indicated by three asterisks (***). Two different polyadenylation sites are indicated by unfilled arrows. The (A/T)GATA(A/G) consensus binding sites (i.e., GATA sites) are enclosed by ovals. The putative SKN-1 binding sites are underlined. The putative HMG protein binding site is indicated with double underlines.

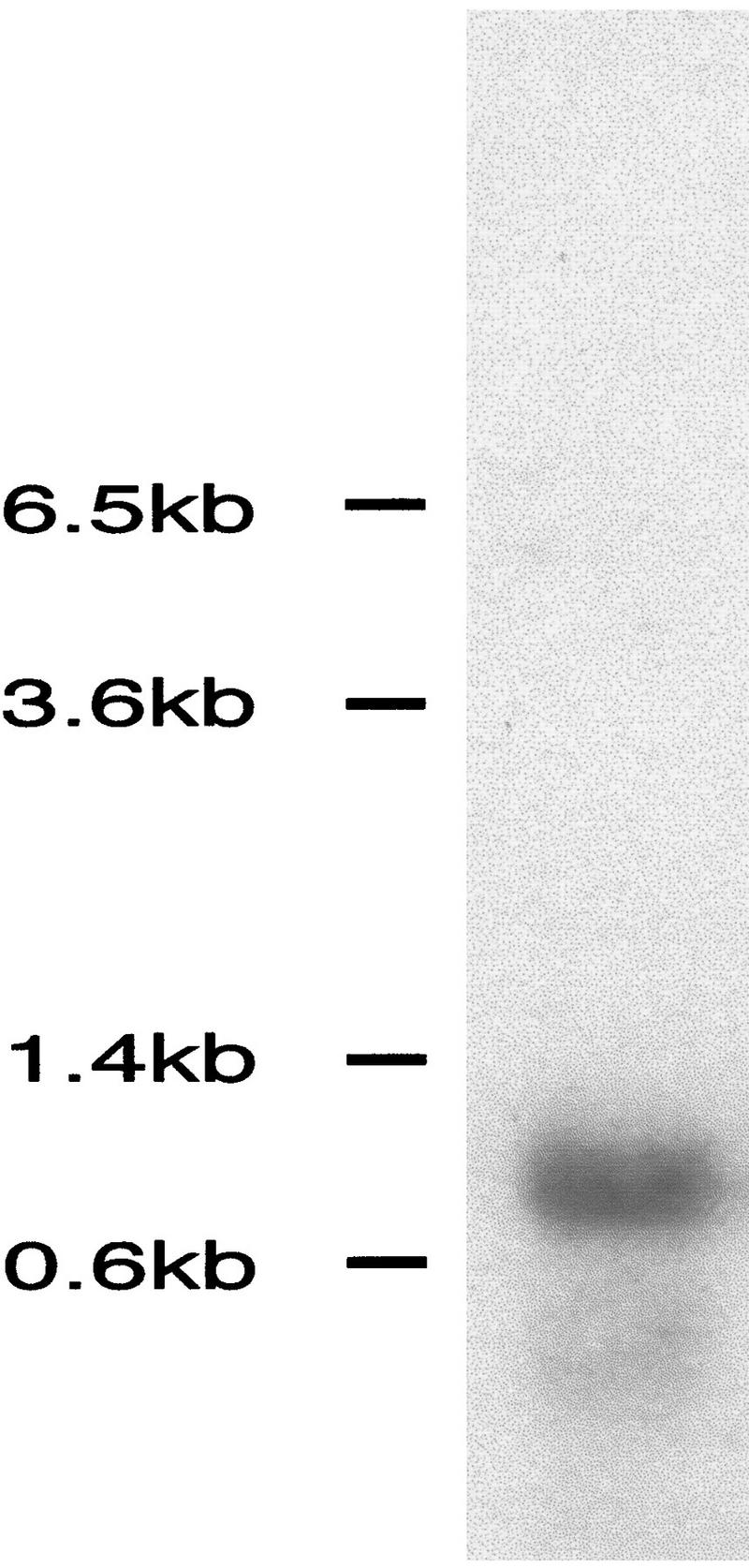

Figure 10.

Northern analysis of end-1 transcript. A single transcript of ∼0.85 kb is detected in poly(A)+-enriched mRNA from mixed stage wild-type embryos using the end-1 cDNA insert from pJZ10 as a probe.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the zinc finger region of the predicted END-1 protein with the single zinc finger region of SERPENT/dABF in Drosophila and the second zinc finger of GATA-4B in Xenopus and GATA-5 in chick. Residues that END-1 shares with at least one of these proteins are shown as white on black letters.

Comparison of the nucleotide sequences of the end-1 cDNA clone with that of the corresponding genomic region revealed four exons flanked by conserved donor and acceptor sequences typical of C. elegans introns (Emmons 1988). Examination of the sequences upstream of the coding region suggests the possible existence of cis-acting regulatory sites for known regulators of endoderm formation in C. elegans (Fig. 9). A single match to the consensus binding motif of HMG-box-containing proteins (Laudet et al. 1993; possibly recognized by the POP-1 HMG-box-containing maternal protein), six consensus binding site sequences for the maternal SKN-1 DNA-binding protein (Blackwell et al. 1994), and seven matches to the consensus GATA-binding site are present in the upstream region (Fig. 9).

end-1 transcripts are present specifically in the E cell and early E lineage

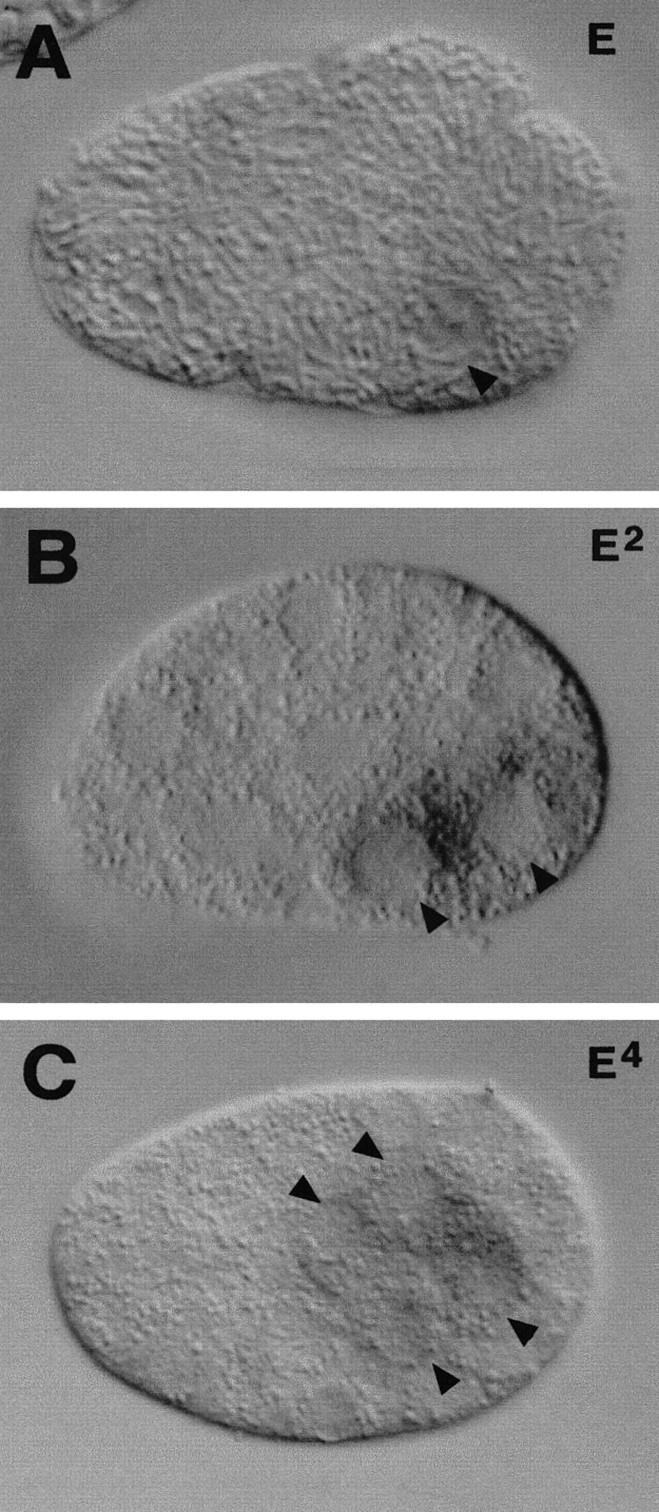

end-1 RNA is first detected by in situ hybridization in the E cell of an 8-cell embryo and becomes more abundant in the daughters of E by the 15-cell stage (Fig. 12). The strongest signal was detected at the 20- to 30-cell stage; however, the message is at low abundance at all stages that it is detected (Fig. 12). Transcripts were undetectable after the division of the E daughters (50- to 100-cell stage). No end-1 transcripts were detected outside the E lineage at any stage in embryogenesis.

Figure 12.

end-1 transcript expression in wild-type embryos. In situ hybridization shows that end-1 mRNA is expressed only in the E lineage. end-1 mRNAs are first detected in the E cell of an eight-cell embryo (A). Expression is also seen in Ea and Ep of a 15-cell embryo (B) and in the four granddaughters of E in an ∼50-cell embryo (C). The arrowheads point to E and its descendants. Anterior is at the left, and dorsal is at the top.

Discussion

The zygotic genome is necessary for endoderm specification

Previous genetic studies on endoderm specification in C. elegans have focused on maternally expressed genes that determine which early blastomere adopts the E fate (Kemphues et al. 1988; Bowerman et al. 1992; Mello et al. 1992; Lin et al. 1995; Rocheleau et al. 1997; Thorpe et al. 1997). Several observations have suggested that zygotically expressed genes might also act in specifying the E-cell fate and the unique properties of the E lineage. In normal development, the daughters of E undergo gastrulation before their division and subsequently divide later than the daughters of MS, the sister of E. When zygotic transcription is inhibited by blocking synthesis of RNA polymerase with antisense RNA or α-amanitin, the daughters of E divide precociously, do not gastrulate normally, and fail to produce gut differentiation markers (Edgar et al. 1994; Powell-Coffman et al. 1996). Similar defects are observed in skn-1 maternal mutants (Bowerman et al. 1992). skn-1 encodes an apparent transcription factor that is presumed to specify the E lineage by regulating expression of one or more zygotic genes (Bowerman et al. 1993). Here, we describe the identification of a small genomic region, the EDR, that appears to contain such a zygotic gene. EDR deficiency embryos fail to produce differentiated endoderm and show premature division and defective gastrulation of the E daughters, similar to the phenotypes observed in skn-1 mutants or when zygotic transcription is blocked.

A gene from the EDR, end-1, is capable of restoring endoderm differentiation, a normal E-cell lineage, and normal gastrulation of the E daughters to deficiency embryos. These results suggest that end-1 may be one of the genes that account for the requirement of zygotic transcription in controlling the unique properties of the E lineage.

Maternal and zygotic regulation of endoderm specification

Two maternally controlled pathways appear to specify endoderm in early C. elegans embryos: One involves an inductive signal from the P2 blastomere via the Wnt pathway (Goldstein 1992, 1993; Rocheleau et al. 1997; Thorpe et al. 1997); the other requires maternal SKN-1 (Bowerman et al. 1992, 1993). When either pathway is disrupted, the E blastomere adopts a fate distinct from that of the normal E: In the absence of SKN-1, E becomes a C-like cell (Bowerman et al. 1992); when the P2 inductive signal is removed, E adopts an MS-like fate (Goldstein 1992, 1993).

Two maternally expressed putative transcription factors, SKN-1 and PAL-1, are present in the E blastomere of wild-type embryos. Genetic and molecular studies suggest that E development requires high levels of SKN-1 (Bowerman et al. 1992, 1993) and that this factor blocks PAL-1 activity (Hunter and Kenyon 1996). In EDR deficiency embryos, E is transformed to a C-like cell, reminiscent of the maternal skn-1 phenotype (Bowerman et al. 1992). Because the fate of a wild-type C blastomere requires PAL-1 activity (Hunter and Kenyon 1996), this result suggests that PAL-1 becomes active in the E lineage in EDR deficiency embryos. There are several models that are compatible with these observations. For example, SKN-1 might directly activate the expression of a gene such as end-1 in the EDR, and end-1 might in turn repress the transcription of genes that would otherwise be activated by PAL-1. The presence of SKN-1 consensus binding sites (Blackwell et al. 1994) upstream of the end-1 coding region is consistent with such a possibility; future experiments should determine whether these sites play a role in end-1 expression.

Induction of endoderm via the Wnt pathway at the four-cell stage may cause an E-inhibiting factor to be inactivated in the E cell (Goldstein 1995). When the inductive signal is absent, such a factor would be present in the E lineage, resulting in an E-to-MS transformation. POP-1, which shares structural similarity to vertebrate LEF-1 (Travis et al. 1991) and which is present at low levels in E and high levels in MS, is a candidate for such a factor (Lin et al. 1995). Elimination of POP-1 causes MS to adopt an E fate. Therefore, the Wnt signal appears to restrict endoderm development to the E lineage by lowering the levels of the POP-1 protein in the E cell. As shown here, the ability of MS to produce intestine in the absence of POP-1 is dependent on zygotic activity of the EDR. The presence of an HMG box consensus binding site upstream of end-1 is consistent with the notion that POP-1 might directly repress end-1 expression in the MS lineage, thereby preventing MS from adopting an E fate. Thus, end-1 may be an immediate downstream target of the Wnt signaling pathway.

The transition from maternal to zygotic gene control has not been identified for any cell fate decision in C. elegans embryos. The early defects in the EDR deficiency embryos and early expression of end-1 transcripts in the E cell suggest that end-1 may be directly acted upon by maternal gene products, hence defining such a maternal-to-zygotic transition in the specification of cell fate.

END-1, GATA factors, and endoderm development

end-1 encodes a GATA transcription factor-like protein. GATA factors generally contain a DNA-binding domain consisting of two similar C4 zinc fingers and regulate transcription of various target genes generally by binding to consensus WGATAR sequences (Evans et al. 1988; Lee et al. 1991; Zon et al. 1991). GATA factors have been implicated in endoderm development in other animals (e.g., Arceci et al. 1993; Laverriere et al. 1994). Of particular note, Drosophila SERPENT, a GATA factor that, like END-1, contains only a single zinc finger, appears to be essential for the formation of endoderm (Reuter 1994; Rehorn et al. 1996). In serpent mutants, the midgut, which is endodermally derived, is not made and tissue typical of the ectodermally derived foregut and hindgut is present in the region of the alimentary canal normally occupied by midgut (Reuter 1994). A transformation of endoderm to ectoderm in the absence of serpent function is reminiscent of the E → C (endoderm → ectoderm + mesoderm) cell fate transformation that we observe in EDR deficiency embryos. Our findings and those of Rehorn et al. (1996) suggest that the molecular mechanisms that specify endoderm may be conserved among animals. Several vertebrate GATA factors are also expressed in endodermal tissues, where they may also perform fuctions in endoderm development (Evans et al. 1988; Laverriere et al. 1994).

Previous studies of intestine-specific gene expression suggest that END-1 might directly activate expression of genes involved in differentiation of the intestine. In C. elegans, several intestine-specific differentiation genes, including ges-1 and vit-2, contain GATA regulatory sequences required for gut-specific transcription (MacMorris et al. 1992; Stroeher et al. 1994). Our observation that ges-1 is not expressed in embryos carrying deletions of end-1 (data not shown) is consistent with the view that END-1 may directly activate ges-1 transcription. In addition, END-1 might also regulate its own expression, as suggested by the presence of GATA consensus sites upstream of the end-1 coding sequence near other putative regulatory elements. Such autoregulation has been proposed for the mouse and chicken GATA-1 genes (Hannon et al. 1991; Tsai et al. 1991).

Is end-1 part of a gene complex required for endoderm specification?

Although end-1 is sufficient to promote endoderm differentiation in EDR deficiency embryos, a number of observations suggest that end-1 may not, by itself, be absolutely required to specify endoderm. Despite considerable efforts, including an extensive lethal screen targeted to the EDR and a number of genome-wide screens in which many alleles of other genes were identified, we have been unable to generate mutations in any single zygotic gene that result in a penetrant absence of gut (S. Gendreau, R. Hill, J. Priess, and J. Rothman, unpubl.). In addition, although injection of antisense RNA has often been found to result in phenocopies of loss-of-function mutations in many genes required for normal embryonic development in C. elegans (e.g., Guo and Kemphues 1995), we have found that injection of antisense end-1 RNA into wild-type hermaphrodites failed to result in any progeny lacking an intestine (J. Zhu, unpubl.).

These observations lead us to suggest that there may be at least two functionally redundant genes that comprise a gene complex within the EDR required to specify the endoderm. Although deficiencies such as itDf2 would eliminate such a gene complex, revealing its essential role in endoderm development, loss of one gene in the complex would not result in the penetrant absence of endoderm. Recent experiments (E. Newman-Smith, J. Zhu, and J. Rothman, unpubl.) have implicated a second gene ∼40 kb from end-1 within the EDR that rescues the endoderm differentiation defect of EDR deficiencies, consistent with the notion that the EDR contains a gene complex required zygotically to specify the endoderm in C. elegans. This second gene encodes an apparent zinc finger transcription factor that is not related to GATA factors. This observation implies that, unlike a number of cases of genetic redundancy in C. elegans (e.g., Lambie and Kimble 1991), this redundancy is not an example of recently duplicated genes; rather, the presence of two dissimilar but redundant genes might indicate a common regulatory mechanism to which these genes are subjected.

Materials and methods

Worm strains and alleles

All stocks were derived from wild-type C. elegans variety Bristol, strain N2 (Brenner 1974). Nematodes were grown at 20°C unless otherwise indicated. The genetic markers and deficiencies used were ced-1 (e1735) I, unc-42(e270) V, dpy-21(e428) V, him-5(e1467) V, sqt-3(sc63), egl-1(n986), unc-76(e911), itDf2 V, nDf42 V, yDf8 V, yDf9 V, arDf1 V, zuDf2 V, wDf4 V, wDf3 V. The strain containing arDf1 was provided by J. Shaw (University of Minnesota, St. Paul). All other strains are available from the C. elegans Genetics Center. JR70 is ced-1; itDf2/dpy-21 unc-42. JJ1035 is zuDf2/sqt-3 egl-1 unc-76. MT2560 is sqt-3 egl-1 unc-76.

Nomarski microscopy and immunofluorescence

Methods for mounting and viewing C. elegans embryos by Nomarski microscopy have been described previously (Sulston et al. 1983). Embryos were fixed and stained for immunofluorescence as described (Sulston and Hodgkin 1988). Deficiency mutant embryos were collected for Nomarski microscopy and immunofluorescence ∼14–18 hr after being laid or after wild-type embryos hatched, unless otherwise stated. Antibodies NE8/4C6 (Goh and Bogaert 1991), 3NB12 (Priess and Thomson 1987), and 1CB4 (Okamoto and Thomson 1985) were obtained from the MRC-Cambridge monoclonal antibody collection. Anti-LIN-26 antibody was a generous gift of Dr. M. Labouesse (IGBMC, CNRS, Illkirch, France). Anti-rabbit and anti-mouse fluorescein-conjugated antibodies were obtained from Sigma.

Antisense RNA injections

pop-1 antisense RNA (a gift from Dr. R. Lin) was prepared from pRL160 as described in Lin et al. (1995). pop-1 antisense RNA was injected into both distal arms of the gonad of mid-L4 N2 or JJ1035 hermaphrodites. Injected P0 animals were placed onto individual plates. N2 animals were transferred every 12 hr to set up F1 cohorts that were examined 6–12 hr later. JJ1035 animals were induced to lay eggs by placing them every 12 hr onto culture plates into which one-tenth volume of 10 mg/ml of serotonin had been absorbed recently (Trent et al. 1983), and embryos laid within the next hour were analyzed. All animals from individual F1 cohorts with a penetrant pop-1 antisense effect were analyzed under Nomarski and polarized light optics for the presence of intestine.

Laser ablation and lineage analysis

Eggs were cut from gravid JJ1035 or MT2560 hermaphrodites. Young one- to four-cell-stage embryos were collected in M9 and transferred onto 3% agarose pads, covered with a coverslip, and sealed with Vaseline according to Sulston et al. (1983). A VSL-337 nitrogen laser (Laser Science, Inc.) attached to a laser ablation unit (Photonic Instruments, Inc., Arlington Heights, IL) was used for ablations. The E blastomere was isolated by ablation of ABa, ABp, P2, and MS. The C blastomere was isolated by ablating ABa, ABp, EMS, and P3 as described elsewhere (Mello et al. 1992). Ablations were performed at 22.5°C–23.5°C. Following ablations, embryos were incubated in humidity chambers at 22.5°C–23.5°C for 9–12 hr.

Embryos were scored for the presence of intestine, hypodermis, and muscle under DIC optics by the criteria of Bowerman et al. (1992). The presence of intestine was also independently scored by the birefringence of gut granules under polarization optics (Laufer et al. 1980). Embryos were then transferred in M9 to poly-l-lysine-coated slides for immunostaining. Embryos were fixed according to Albertson et al. (1978), rehydrated in TBS–Tween 20, and stained with two of the following three antibodies diluted in 10% normal goat serum (NGS) for 1 hr: mAb 5.6 (Miller et al. 1983), mAb 1CB4 (Okamoto and Thomson 1985), and rabbit anti-LIN-26 (Labouesse et al. 1996). Secondary antibodies were used as follows: sheep anti-rabbit IgG Cy3 conjugate C-2306 (Sigma), goat anti-mouse IgG, and IgM fluorescein conjugate AMI0708 (Tago Immunologicals, Camarillo, CA).

Cell lineage analysis (Sulston et al. 1983) was performed by four-dimensional time-lapse analysis (Schnabel 1991; Hird and White 1993; Moskowitz et al. 1994). Four-cell embryos were collected after cutting open gravid heterozygous deficiency mothers in M9 buffer and mounted on agar pads as described above. Recordings were set up for at least 3 hr for early lineage analysis. The E lineage analysis in both unrescued and rescued itDf2 homozygotes was performed from a 6- to 7-hr recording. After recording, the embryos were allowed to develop on the slide overnight. The homozygous deficiency embryos were identified according to their characteristic terminal morphology and the absence of gut granules.

Endpoint mapping of deficiencies by PCR

The endpoints of deficiencies were mapped on the physical map by using primer sets from the relevant region and PCR (Fig. 6). DNA was extracted from embryos homozygous for the given deficiency as described (Williams et al. 1992) and amplified by PCR with control primers to confirm the presence of DNA. PCR was performed as described in Williams et al. (1992). Tester primer sets were derived from cDNA sequences that were available through ACeDB. Primers JZ 7,8 were derived from the cDNA cm7f6; JZ 17,18 were obtained from org-1 sequence kindly provided by Dr. Abby Telfer (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia).

Generation of transgenic animals and scoring for rescued animals

Generally, hermaphrodites were injected with a mixture of pRF4 (100 μg/ml) and a test DNA (10 μg/ml) as described by Mello et al. (1991). Transgenic worms were selected based on the expression of the dominant rol-6 (su1006) gene present in pRF4 that causes worms to roll; Roller lines were established after two generations of transmission of the Roller phenotype. For injection of cosmid DNAs, 1–10 μg/ml of cosmid DNA was used together with 100 μg/ml of pRF4 DNA. For each test DNA, multiple Roller lines were established at 20°C in an itDf2 heterozygous background (JR70: ced-1; itDf2/unc-42, dpy-21). Rolling itDf2 heterozygous hermaphrodites were cloned on individual plates and allowed to lay eggs for ∼24 hr. Fourteen to eighteen hours after removing hermaphrodites, arrested embryos were collected and mounted for Nomarski microscopy to examine for the presence of gut granules and gut cells.

Pools of cosmids were injected into young heterozygous deficiency adults to test for rescuing activity. Three cosmids were found containing the rescuing activity: K10F6, R7, and T26F2. Subclones of K10F6 and the end-1 minigene were also tested for rescuing activity (also see Fig. 6). The number of lines obtained from representative DNA fragments that gave positive rescue and percent rescued homozygous deficiency embryos (number of homozygous mutant embryos containing gut granules out of number of total mutant embryos) were as follows: K10F6, 1 line, 47% (68 of 146); 5.5-kb subclone from K10F6, 5 lines, 50% (11 of 22), 85% (11 of 13), 70% (30 of 43), 32% (20 of 63), 33% (16 of 48); the end-1 minigene construct, 1 line, 65% (15 of 23).

Molecular analyses and cDNA cloning

Standard methods (Sambrook et al. 1989) were used for molecular analyses except where indicated. A 5.5-kb KpnI–PstI fragment from K10F6 was used as a probe to screen an embryonic λgt11 cDNA library (kindly provided by Peter Okkema, University of Illinois, Chicago). Approximately 400,000 plaques were screened, and 15 positive clones were isolated. The 4-kb rescuing fragment from K10F6 was used as a probe for additional screens. Eight positive clones were isolated: one with a 2.5-kb insert, three with 1.3-kb inserts, three with 0.85-kb inserts, and one with a 0.8-kb insert. The 2.5-kb insert appeared to belong to a unique class and was not studied further. The other seven clones were partially sequenced. The sequence data indicated that all seven clones shared the same sequence, although the 1.3-kb clones appear to be chimeric, containing the 0.85-kb sequence at their 3′ end. The smaller clones, 0.8 and 0.85 kb in size, were identical along most of their lengths. However, the 0.8-kb cDNA lacks 50 bases at its 5′ end, and different polyadenylation sites were apparently used to generate the messages from which these cDNAs were derived (Fig. 9).

Sequencing of the end-1 clone and 5′ end determination

A series of nested deletions of the 4-kb KpnI–SacI genomic subclone was made using exonuclease III and mung bean nuclease according to manufacturer’s protocols (Promega). These deletions were sequenced using Sequenase (U.S. Biochemical) by the dideoxy chain terminator method (Sanger et al. 1977). Some sequences were determined by the University of Wisconsin Genetics Center Program Automatic Sequencing Facility. Both strands of the 4-kb genomic fragment and cDNA were sequenced.

To determine the 5′ end of the end-1 gene, 5′-RACE was perfomed with Marathon RACE–PCR kit (Clonetech). Total RNA was prepared from mixed stage wild-type C. elegans embryos and poly(A)+ RNA was selected using the Oligotex kit (Qiagen), according to manufacturer’s instructions. The mRNA was used as a template in the Marathon RACE–PCR. Sequence containing the 5′ end of end-1 was amplified by PCR and subcloned into the pT7 blueT vector (Novagen). Sequence analysis was performed using the BLAST program (Altschul et al. 1990) within the Genetics Computer Group package (Madison, WI). The longest clone amplified by 5′-RACE contained an extra 5 nucleotides at the 5′ end relative to the 0.85-kb clone. Hence, full-length end-1 transcripts start at or very close to this position. They appear not to be trans-spliced, as was further confirmed by RT–PCR analysis using primers specific for the SL1 and SL2 leaders (Krause and Hirsh 1987; Bektesh et al. 1988; Zorio et al. 1994) (data not shown).

Northern blot analysis

Hypochlorite treatment was used to obtain early embryos for RNA extraction. Briefly, 6–8 ml of N2 gravid adults were collected from 50- to 100-mm plates. Worm pellets were washed several times with M9 buffer. Ten milliliters of hypochlorite solution (1 n NaOH, one-tenth commercial Clorox in H2O) per ml of worm pellet was used to treat the adult worms at room temperature for ∼10 min. After resuspending in 5 ml of M9 buffer, embryos were spun down at 3K for 1 min. The pellet was washed several times with M9 buffer. Embryos were frozen at −70°C until needed.

Total RNA was prepared as described by Austin and Kimble (1989). Poly(A)+ RNA was prepared using oligo(dT) Oligotex combi kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocols (Qiagen). Northern blot analysis was performed by electrophoresing 2.5 μg of poly(A)+ mRNA on 1% agarose–formaldehyde gels according to standard protocols. The end-1 cDNA insert from pJZ10 was used as a template to generate the DNA probe using the Prime-a-gene kit (Promega). Hybridization and washes were performed at 48°C.

In situ hybridization to end-1 RNA

In situ hybridization was performed as described (Seydoux and Fire 1994). N2 embryos were collected by hypochlorite treatment as described above. Embryos were then mounted on poly-l-lysine slides and processed as described. Herring sperm DNA (10 μg/ml) was used in place of salmon sperm DNA. An end-1 cDNA clone, pJZ10, was linearized with HindIII for the T3 primer to generate the sense probe and PstI for the T7 primer to generate the antisense probe. Undiluted probes were used in all in situ experiments. Alkaline phosphatase detection reactions were allowed to proceed at room temperature for 1.5 hr.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to S. Gendreau for isolating wDf3 and wDf4, two deficiencies used in this study. We thank M. Labouesse for LIN-26 antibody, J. Shaw, K. Kemphues, and B. Meyer for deficiency strains, A. Telfer for ogr-1 primers, R. Lin for pop-1 antisense RNA, P. Okkema for the cDNA library, A. Coulson and the C. elegans genome consortium for all cosmids used, and J. Kimble’s and P. Anderson’s laboratories for valuable discussions, advice, and use of equipment. We thank Bill Smith and members of the Rothman laboratory for insightful discussions and comments on the manuscript. Some of the strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). P.H. was supported by an NIH Cell and Molecular Biology Predoctoral Training Grant. A.S. was supported by a Human Frontiers Science Program Organization fellowship, a Naito Foundation fellowship, and a Leukemia Society of America Special Fellowship. R.H. was supported by a fellowship from the Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund for Cancer Research. This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute to J.R.P. and by grants from the NIH (GM 48137), the National Science Foundation (IBN-9506089), the March of Dimes, a Searle Scholars Award from the Chicago Community Trust, and a Shaw Scientists Award from the Milwaukee Foundation to J.H.R.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Note added in proof

The GenBank accession no. for end-1 is AF026555.

Footnotes

E-MAIL rothman@lifesci.lscf.ucsb.edu; FAX (805) 893-4724.

References

- Aamodt EJ, Chung MA, McGhee JD. Spatial control of gut-specific gene expression during Caenorhabditis elegans development. Science. 1991;252:579–582. doi: 10.1126/science.2020855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertson DG, Sulston JE, White JG. Cell cycling and DNA replication in a mutant blocked in cell division in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1978;63:165–178. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers W, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arceci R, King AAJ, Simon MC, Orkin SH, Wilson DB. Mouse GATA-4: A retinoic acid-inducible GATA-binding transcription factor expressed in endodermally derived tissues and heart. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2235–2246. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin J, Kimble J. Transcript analysis of glp-1 and lin-12, homologous genes required for cell interactions during development of C. elegans. Cell. 1989;58:565–571. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90437-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bektesh S, Van Doren K, Hirsh D. Presence of the Caenorhabditis elegans spliced leader on different mRNAs and in different genera of nematodes. Genes & Dev. 1988;2:1277–1283. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.10.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell TK, Bowerman B, Priess JR, Weintraub H. Formation of a monomeric DNA binding domain by skn-1 bZIP and homeodomain elements. Science. 1994;266:621–628. doi: 10.1126/science.7939715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman B, Eaton BA, Priess JR. skn-1, a maternally expressed gene required to specify the fate of ventral blastomeres in the early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1992;68:1061–1075. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90078-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman B, Draper BW, Mello CC, Priess JR. The maternal gene skn-1 encodes a protein that is distributed unequally in early C. elegans embryo. Cell. 1993;74:443–452. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80046-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan AE, McIntosh JR. Mapping the distribution of differentiation potential for intestine, muscle, and hypodermis during early development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell. 1985;41:923–932. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deppe U, Schierenberg E, Cole T, Krieg C, Schmitt D, Yoder B, Von Ehrenstein G. Cell lineages of the embryo of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1978;75:376–380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.1.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar LG, McGhee JD. Embryonic expression of a gut-specific esterase in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1986;114:109–118. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90387-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— DNA synthesis and the control of embryonic gene expression in C. elegans. Cell. 1988;53:589–599. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90575-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar LG, Wolf N, Wood WB. Early transcription in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Development. 1994;120:443–451. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.2.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons SW. The genome. In: Wood WB, editor. The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. pp. 47–80. [Google Scholar]

- Evans T, Teitman M, Felsenfeld G. An erythrocyte specific DNA binding factor recognizes a regulatory sequence common to all chicken globin genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:5976–5980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh PY, Bogaert T. Positioning and maintenance of embryonic body wall muscle attachments in C. elegans requires the mup-1 gene. Development. 1991;111:667–681. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.3.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein B. Induction of gut in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Nature. 1992;357:255–257. doi: 10.1038/357255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Establishment of gut fate in the E lineage of C. elegans: The roles of lineage-dependent mechanisms and cell interactions. Development. 1993;118:1267–1277. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.4.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— An analysis of the response to gut induction in the C. elegans embryo. Development. 1995;121:1227–1236. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.4.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Kemphues KJ. par-1, a gene required for establishing polarity in C. elegans embryos, encodes a putative Ser/Thr kinase that is asymmetrically distributed. Cell. 1995;8145:611–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon R, Evans T, Felsenfeld G, Gould H. Structure and promoter activity of the gene for the erythroid transcription factor GATA-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:3004–3008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hird SN, White JG. Cortical and cytoplasmic flow polarity in early embryonic cells of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:1343–1355. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.6.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter CP, Kenyon C. Spatial and temporal controls target pal-1 blastomere-specification activity to a single blastomere lineage in C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1996;87:217–226. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemphues KJ, Priess JR, Morton DG, Cheng N. Identification of genes required for cytoplasmic localization in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1988;52:311–320. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause M, Hirsh D. A trans-spliced leader sequence on actin mRNA in C. elegans. Cell. 1987;49:753–761. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90613-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouesse M, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR. The Caenorhabditis elegans LIN-26 protein is required to specify and/or maintain all non-neuronal ectodermal cell fates. Development. 1996;122:2579–2588. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambie EJ, Kimble J. Two homologous regulatory genes, lin-12 and glp-1, have overlapping functions. Development. 1991;112:231–240. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.1.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet V, Stehelin D, Clevers H. Ancestry and diversity of the HMG box superfamily. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:2493–2501. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.10.2493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufer JS, Bazzicalupo P, Wood WB. Segregation of developmental potential in early embryos of Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell. 1980;19:569–577. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(80)80033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laverriere AC, MacNeill C, Mueller C, Poelmann RE, Burch JBE, Evans T. GATA-4/5/6, a subfamily of three transcription factors transcribed in developing heart and gut. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23177–23184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ME, Temizer DH, Clifford JA, Quertermous T. Cloning of the GATA-binding protein that regulates endothelin-1 gene expression in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:16188–16192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R, Thompson S, Priess JR. pop-1 encodes an HMG box protein required for the specification of a mesoderm precursor in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1995;83:599–609. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMorris M, Broverman S, Greenspoon S, Lea K, Madej C, Blumenthal T, Spieth J. Regulation of vitellogenin gene expression in transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans: Short sequences required for activation of the vit-1 promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1652–1662. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.4.1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello CC, Kramer JM, Stinchcomb D, Ambros V. Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: Extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 1991;10:3959–3570. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello CC, Draper BW, Krause M, Weintraub H, Priess JR. The pie-1 and mex-1 genes and maternal control of blastomere identity in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1992;70:163–176. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90542-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello CC, Schubert C, Draper B, Zhang W, Lobel R, Priess JR. The PIE-1 protein and germline specification in C. elegans embryos. Nature. 1996;382:710–712. doi: 10.1038/382710a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DM, Ortiz I, Berliner GC, Epestein HF. Differential localization of two myosins within nematode thick filaments. Cell. 1983;34:477–490. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz IP, Gendreau SB, Rothman JH. Combinatorial specification of blastomere identity by glp-1-dependent cellular interactions in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1994;120:3325–3338. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.11.3325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusse R, Varmus HE. Wnt genes. Cell. 1992;69:1073–1087. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90630-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto H, Thomson JN. Monoclonal antibodies which distinguish certain classes of neuronal and supporting cells in the nervous tissue of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 1985;5:643–653. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-03-00643.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Coffman JA, Knight J, Wood WB. Onset of C. elegans gastrulation is blocked by inhibition of embryonic transcription with an RNA polymerase antisense RNA. Dev Biol. 1996;178:472–483. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priess JR, Hirsh DI. Caenorhabditis elegans morphogenesis: The role of the cytoskeleton in elongation of the embryo. Dev Biol. 1986;117:156–173. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priess JR, Thomson JN. Cellular interactions in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1987;48:241–250. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90427-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehorn K-P, Thelen H, Michelson AM, Reuter R. A molecular aspect of hematopoiesis and endoderm development common to vertebrates and Drosophila. Development. 1996;122:4045–4056. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.4023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter R. The gene serpent has homeotic properties and specifies endoderm versus ectoderm within the Drosophila gut. Development. 1994;120:1123–1135. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.5.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocheleau CE, Downs WD, Lin R, Wittmann C, Bei Y, Cha Y, Ali M, Priess JR, Mello CC. Wnt signaling and an APC-related gene specify endoderm in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1997;90:707–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schierenberg E, Wood WB. Control of cell-cycle timing in early embryos of Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1985;107:337–354. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90316-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel R. Cellular interactions involved in the determination of the early C. elegans embryo. Mech Dev. 1991;34:85–99. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(91)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seydoux G, Fire A. Soma-germline asymmetry in the distributions of embryonic RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1994;120:2823–2834. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.10.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seydoux G, Mello CC, Pettitt J, Wood WB, Priess JR, Fire A. Repression of gene expression in the embryonic germ lineage of C. elegans. Nature. 1996;382:713–716. doi: 10.1038/382713a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroeher VL, Kennedy BP, Millen KJ, Schroeder DF, Hawkins MG, Goszczynski B, McGhee JD. DNA-protein interactions in the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo: Oocyte and embryonic factors that bind to the promoter of the gut-specific ges-1 gene. Dev Biol. 1994;163:367–380. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J, Hodgkin J. Methods. In: Wood WB, editor. The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. pp. 587–606. [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983;100:64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terns RM, Kroll-Conner P, Zhu J, Chung S, Rothman JH. A deficiency screen for zygotic loci required for establishment and patterning of the epidermis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1997;146:185–206. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe CJ, Schlesinger A, Carter JC, Bowerman B. Wnt signaling polarizes an early C. elegans blastomere to distinguish endoderm from mesoderm. Cell. 1997;90:695–705. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80530-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis A, Amsterdam A, Belanger C, Grosschedl R. Lef-1, a gene encoding a lymphoid-specific protein with an HMG domain, regulates T-cell receptor α enhancer function. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:880–894. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.5.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trent C, Tsung N, Horvitz HR. Egg-laying defective mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1983;104:619–647. doi: 10.1093/genetics/104.4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SF, Strauss E, Orkin SH. Functional analysis and in vivo footprinting implicate the erythroid transcription factor GATA-1 as a positive regulator of its own promoter. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:919–931. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.6.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BD, Schrank B, Huynh C, Shownkeen R, Waterston RH. A genetic-mapping system in Caenorhabditis elegans based on polymorphic sequence-tagged sites. Genetics. 1992;131:609–624. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.3.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zon LI, Mather C, Burgess S, Bolce ME, Harland RM, Orkin SH. Expression of GATA-binding proteins during embryonic development in Xenopus laevis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:10642–10646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorio D, Cheng N, Blumenthal T, Speith J. Operons as a common form of chromosomal organization in C. elegans. Nature. 1994;372:270–272. doi: 10.1038/372270a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]