Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the present study was to develop a short, easy-to-use, and acceptable psychosocial screening instrument specific for breast cancer patients.

Methods

Before the start of adjuvant chemotherapy, 164 (98.8%) women completed the Psychosocial Distress Questionnaire-Breast Cancer (PDQ-BC) as part of routine care. The PDQ-BC consists of questions about psychological risk factors (i.e., trait anxiety and (lack of) social support), psychosocial problems (i.e., state anxiety and depressive symptoms), social problems, physical problems, body image, financial problems, sexual problems, clinical factors (type of surgery, adjuvant treatment other than chemotherapy and psychiatric morbidity), and demographic factors (marital status, age, and age of children).

Results

On average, patients indicated that they needed 5 min to complete the PDQ-BC. All subscales were significantly correlated with each other, except the correlations of social support with physical problems and body image. Confirmatory factor analysis supported the internal structure of the PDQ-BC (comparative fit index = 0.95 (χ 2(24) = 43.3), p = 0.009; non-normed fit index = 0.91; root mean square error of approximation = 0.073). The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas) of the subscales trait anxiety, state anxiety, depressive symptoms, body image, social problems, and physical problems were 0.88, 0.85, 0.86, 0.79, 0.42, and 0.69, respectively.

Conclusion

The PDQ-BC is an easy-to-complete, acceptable, non-burdensome, and short screening instrument for routine use in breast cancer patient care. This instrument facilitates a greater awareness of the concerns and needs for breast cancer patients care during treatment with chemotherapy and the follow-up. It is linked to a good referral system to guide allocation to the different levels of psychosocial care providers.

Keywords: Oncology, Cancer, Psychosocial, Breast cancer, Screening, Psychosocial problems

Introduction

Among women, breast cancer is the most common type of malignancy worldwide. Every year, more than 1.2 million patients are diagnosed with breast cancer [1]. In the Netherlands, one in every nine women will be diagnosed with breast cancer during her life [2]. The prevalence rate of breast cancer has increased over the recent years as a result of earlier detection and the use of better adjuvant treatments [3]. Multimodality treatment regimens improve survival outcome but also contribute to a prolonged period of medical interventions with concurrent psychosocial problems. Patients may experience a number of psychosocial problems (i.e., a combination of psychological and social problems), notably psychological problems (i.e., anxiety, depressive symptoms) [4, 5], psychosexual functioning (i.e., impairments in sexual functioning, decreased libido, and relational problems) [5–7], body image [8, 9], physical functioning (fatigue) [10, 11], social problems (i.e., household activities and job) [12], and financial problems [13]. These psychosocial problems are experienced by 10% to 50% of the breast cancer patients shortly after diagnosis and medical treatment [4, 14–16]. Concerning the psychological problems, different studies reported prevalence rates ranging from 14% to 54% for depression [15, 17] and prevalence rates for anxiety ranging from 8.6% to 49% [5]. This variation in prevalence reflects differences in screening instruments, assessment times, definitions of anxiety and depression, and the stages of disease [18].

Studies have shown that several factors are associated with an increased risk for developing psychosocial problems, e.g., trait anxiety. Women with high scores on trait anxiety have the tendency to respond to situations perceived as threatening with a rise in anxiety intensity [19]. These women scored low on quality of life (QoL) [20, 21] and high on fatigue and depressive symptoms [22], irrespective of diagnosis. Furthermore, lower levels of depressive symptoms and a greater sense of well-being were reported when patients experienced adequate social support, especially from family and close friends [23]. This indicates that a lack of social support could be a risk factor for depressive symptoms.

After treatment, patients frequently report a loss of sexual interest and sexual enjoyment [5]. These problems may be directly caused by the side effects of adjuvant therapies, especially chemotherapy [6] and hormonal therapy [7]. Higher degree of impairment of body image is reported in patients after mastectomy compared with patients having had breast conserving therapy [8, 9], although the impact of the type of surgery may be related to the patient’s age [24].

Fatigue and pain are the most common physical side effects of treatment of breast cancer. Berger and Higginbottham [10] found that greater levels of fatigue were associated with reporting experiencing more symptoms. Moreover, breast cancer survivors who received chemotherapy may be at higher risk for severe fatigue, which has been associated with depression, pain, and sleep disturbance [11]. Finally, the first year after diagnosis, especially young women seem to suffer from psychosocial problems. One of the explanations is that younger women with breast cancer undergo more aggressive treatment [13]. These well-documented side effects can have devastating short- and long-term psychosocial consequences for patients.

Psychosocial problems are thought to limit the daily activities and influence the overall QoL of breast cancer patients. It is essential that psychosocial problems in patients are recognized at an early stage since early intervention improves outcome [25–27]. This is the main reason why it is very important to assess these problems and to try to facilitate patients to improve QoL. Thus, good oncological care needs to aim at preventing psychosocial problems by timely detection and offering help when needed. A screening instrument to reveal psychosocial problems is, therefore, important.

Nowadays, screening for psychosocial problems in cancer patients receives much attention. The Dutch National Cancer Control Programme has stated as their goal to develop a screening program for psychosocial problems in the Dutch guidelines before the year 2010 [28]. Regarding follow-up in oncology, the National Health Council strongly advocates that psychosocial care should be a regular part of follow-up [29]. To assess psychosocial problems, a number of screening instruments exist [30, 31] of which most are not validated in a Dutch cancer population or only assess psychological problems (i.e., anxiety and depressive symptoms). Two screening instruments have been used and validated in the Netherlands: first, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), which is a 14-item scale inquiring into anxiety and depressive symptoms during the previous week. This scale has shown to be reliable and valid [32]. However, the HADS only assesses two specific psychological factors, which is depression and anxiety. Other relevant aspects have not been incorporated in this screening instrument. Second, the Distress Thermometer (DT) was developed by the American National Comprehensive Cancer Network [26]. It is a frequently used measure to evaluate emotional distress (i.e., social, psychological, and spiritual/religious aspects) in cancer patients. At this moment, it is the instrument of choice in the Netherlands. On a visual analog scale, called the thermometer, patients can indicate their level of distress by indicating a number on a scale from 0 (no distress) to 10 (unbearable distress). Recently, the DT is validated in a Dutch cancer population [33]. The DT has acceptable levels of sensitivity and specificity [34–36]. The DT performs best in relation to distress, but modestly with regard to anxiety and depression [37].

However, the thermometer of the DT is generic and cannot be used for specific referral to various levels of psychosocial care providers, i.e., social worker, psychologist, or psychiatrist. Apart from the thermometer, the DT contains a number of questions regarding physical, psychological, social, and spiritual/religious concerns. The answers provided are only yes/no and do not explore the extent of these problems. In addition, neither the HADS nor the DT identifies risk factors for psychological problems. Moreover, these instruments are not linked to a referral system based on norm scores for referral to the various levels of psychosocial care providers. Therefore, the project group “Verwijs-Wijzer” of the St. Elisabeth Hospital in Tilburg (EZT), the Netherlands, in collaboration with Tilburg University, has developed the Psychosocial Distress Questionnaire-Breast Cancer (PDQ-BC). The aim of the project group was to develop a screening instrument that is multi-dimensional and assesses the most important psychosocial problems and risk factors in breast cancer patients. Moreover, this screening instrument aims to optimize the care providers’ conversation with patients regarding all psychosocial aspects and to give cut-off scores for referral to various levels of psychosocial care providers. The project group consisted of experts in psychosocial care, i.e., social worker, psychologist, psychiatrist, oncology nurse, nurse practitioner, and a member of the psychosocial care department of the Comprehensive Cancer Centre South.

Based on the literature [4–16, 20–23], the PDQ-BC consists of nine scales assessing psychological risk factors (i.e., trait anxiety and (lack of) social support) and state anxiety, depressive symptoms, social problems, physical problems, body image, financial problems, and sexual problems. Scores on the PDQ-BC are linked to a decision tree for referral to the various levels of psychosocial care providers.

The aim of this study was to develop a short, easy-to-use psychosocial screening instrument specific for breast cancer patients (PDQ-BC) and to examine the acceptability, preliminary reliability, and validity of the PDQ-BC. In addition, this study examined whether the referral advice based on the PDQ-BC to the various psychosocial care providers was justified.

Methods

Patients

The pilot study was done from December 2006 until December 2009 at the Department of Medical Oncology of EZT. All breast cancer patients at the outpatient clinic scheduled for adjuvant chemotherapy without a history of a psychiatric disorder were eligible for this study. Patients with a psychiatric disorder often already have coaching by a care provider for psychosocial problems. It was decided that this group was excluded from this study. One hundred and sixty-six women visited the nurse practitioner before chemotherapy was started. One woman was not eligible for participation in this study due to a known psychiatric disease, and one patient was excluded because she found it too difficult to complete the questionnaire. Therefore, 164 women completed the PDQ-BC. This study was approved by the local ethics committee.

Questionnaire

The PDQ-BC consists of nine subscales assessed by 35 questions, of which 31 were selected from existing and valid questionnaires: Center of Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [38], World Health Organization Quality of Life instrument (WHOQOL-100) [39], European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire—Breast (EORTC QLQ BR-23) [40], and the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [19].

The scales trait anxiety (10 questions), depressive symptoms (seven questions), physical problems (four questions), body image (two questions), financial problems (one question), and sexual problems (one question) were developed by selecting items (highest factor loadings) from the above-mentioned existing questionnaires using factor analysis on data from a prospective follow-up study into the role of personality factors on QoL in breast cancer patients [20, 42, 43].

A distinction was made between trait anxiety (how one generally feels; personality factor), a psychological risk factor, and state anxiety (how one feels at the moment), a psychological problem. Therefore, we needed questions assessing trait anxiety and questions assessing state anxiety, thereby increasing the number of questions that assess anxiety. These questions were adapted from the STAI [19].

The questions concerning depressive symptoms were adapted from the CES-D. The CES-D consists of a 20-item self-report scale, assessing the presence and degree of depressive symptoms [38]. The reliability and criterion validity appear to be good for the Dutch population. The questions on physical, financial, and sexual problems are derived from the Dutch version of the WHOQOL-100 [39].

The questions on body image were adapted from the EORTC QLQ BR-23, a reliable and valid supplementary measure of the QOL in breast cancer patients [40, 41].

With regard to state anxiety, an existing and already shortened instrument was used (STAI short form). This reduction from 20 to six questions has been done and validated by others [40, 44, 45]. This shortened instrument has good psychometric properties. It is preferable to use validated scales; therefore, we made no changes to this existing short version.

The only question concerning social support was judged important by the project group for referral to the social worker because social support has shown to be a risk factor. This question was developed by the group and is a combination of two existing questions into social support from the WHOQOL. Because the two questions made a distinction between friends and family and we did not think that this distinction was important for screening, we made a more generic question, leaving out the specific referral to family and friends. Questions about social problems were judged by the project group as relevant for determining whether or not patients should be referred to a social worker. These questions were developed by the project group because no existing questionnaires assessed these topics.

A question on financial problems was added by the project group based on clinical experience of the social worker that problems in this area may increase other psychosocial problems. We have chosen to assess this issue with a question from the WHOQOL that has shown to be a good question in psychometric terms.

Clinical practice has shown that discussing sexuality was perceived not relevant soon after diagnosis and in this stage of adjuvant treatment. At this stage of treatment, patients sometimes get irritated when health professionals discuss sexual issues. Therefore, again, we have chosen one generic sexuality question from the WHOQOL to address the sexuality issue.

Thus, the PDQ-BC consists of nine subscales assessed by 35 questions, with items addressing trait anxiety (10 questions, e.g., “I worry too much over something that really doesn’t matter”), state anxiety (six questions, e.g., “I feel calm”), depressive symptoms (seven questions, e.g., “I feel depressed”), social problems (three questions, e.g., “There are practical problems with regard to my family as a result of the disease and treatment”), social support (one question, “I receive enough support from people around me”), physical problems (four questions, e.g., “I am satisfied with the energy that I have”), body image (two questions, e.g., “I find it difficult to see myself naked”), financial problems (one question, “I worry about money”), and sexual problems (one question, “I have problems with my sexual life”). The questions from the various existing measures were formulated differently. Some questions were formulated with I, and other with you; and other questions were statements. Questions were reformulated in order to get a uniform format. We have chosen to let all questions start with I, because when we asked patients, they found this a more pleasant way of posing the questions. We also wanted a uniform response scale for the entire PDQ-BC to make it easier to complete the measure. Therefore, the response options for all questions are now ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much).

In addition to the PDQ-BC, a number of questions concerned demographic (marital status, age, and age of children) and clinical factors (type of surgery, adjuvant treatment other than chemotherapy, and pre-treatment psychiatric morbidity). The questions on demographic factors and trait anxiety only have to be completed at baseline.

Procedure

All women who were eligible for participation were asked by the nurse practitioner to answer the questions of the PDQ-BC at their own home.

During the visit with the nurse practitioner, the scores were calculated and accompanied by an advice regarding the need for additional psychosocial care. This advice was based on patients’ scores that were compared with predetermined cut-off values. Possible outcomes of the instrument were as follows: no referral, referral to a medical social worker, referral to a psychologist, or referral to a psychiatrist. An advice concerning a referral for psychosocial counseling was discussed with the patient by the nurse practitioner. If needed and after approval by the patient, the patient was seen by one of the psychosocial care providers, depending on the advice that originated from the scores on the various parts of the screening instrument. In case patients were referred to a psychosocial care provider, this care provider was asked to indicate whether the referral was appropriate. The cut-off scores for trait anxiety, state anxiety, and depressive symptoms were derived for the cut-off scores of the original, longer questionnaires. The cut-off scores for the questions taken from the WHOQOL (financial, physical, and sexual problems) [39] and the EORTC-BR23 (body image) [40, 41] were derived from the norm scores. The cut-off scores for the remaining aspects (social problems and social support) were determined during discussions within the project group. These cut-off scores were subsequently tested with 10 patients to see whether these scores resulted in a correct referral. In addition, the project group also decided which combination of scores above the cut-off scores let to a referral to social work, psychology, or psychiatry. For instance, a score slightly above the cut-off value on state anxiety (or depressive symptoms) results in an advice for referral to social work, whereas a combination of scores above the cut-off values for both trait anxiety and state anxiety (or depressive symptoms) resulted in an advice to visit a psychologist. When a patient has extreme high scores on trait anxiety or depressive symptoms, she is referred to psychiatry.

Statistical procedure

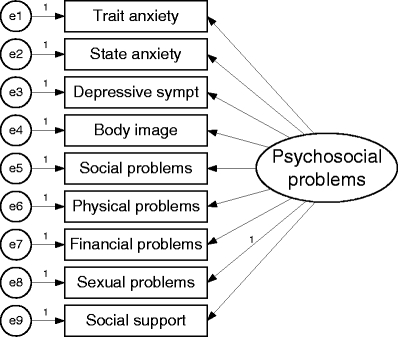

Correlations were calculated between the subscales. For each of the six scales of the PDQ-BC that consists of more than one item, an exploratory factor analysis (method PCA) was performed to examine whether each scale constitutes one factor. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to test whether the a priori structure of the PDQ-BC is suited to a population with breast cancer patients. The hypothesized model is presented in Fig. 1. Goodness of fit was verified by the following fit indices: the comparative fit index (CFI), the non-normed fit index (NNFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The models have a satisfactory to good fit when CFI and NNFI is at least 0.90 and RMSEA is 0.06 or smaller [46]. Internal consistency was examined with Cronbach’s alpha in the total population. Depending on the number of questions in a (sub)scale, Cronbach’s alpha should be at least 0.70 in case of four items or more [47]. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 17.0 was used for all calculations, except for the CFA; these data were processed by AMOS.

Fig. 1.

The hypothesized model

Results

Patient and clinical characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants (N = 164)

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 50.3 ± 8.9 (range 29–69) |

| Living with partner (yes/no) | 138 (84.1)/26 (15.9) |

| Kids at home (yes/no) | 85 (51.8)/79 (48.2) |

| Previously diagnosed with breast cancer (yes/no) | 6 (3.7)/158 (96.3) |

| Previous psychosocial treatment (yes/no) | 33 (20.1)/131 (79.9) |

| Type of surgery | |

| BCT | 47 (28.7) |

| MTC | 116 (70.7) |

| No surgical treatment (due to neoadjuvant chemotherapy) | 1 (0.6) |

| Axillary dissection (yes/no) | 113 (68.9)/51 (31.1) |

Percentages are provided in brackets, except for age

SD standard deviation, BCT breast conserving therapy, MTC mastectomy

Internal structure

Correlations between the subscales are shown in Table 2. All correlations were statistically significant, except the correlations of social support with physical problems and body image are not statistically significant. The subscales trait anxiety, state anxiety, and depressive symptoms have the highest correlations with each other (r’s between 0.70 and 0.80).

Table 2.

Correlations between the subscales of the PDQ-BC

| TAtot | SAtot | DEtot | SOtot | PHYtot | BOtot | Support | Financ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAtot | 0.72 | |||||||

| DEtot | 0.72 | 0.79 | ||||||

| SOtot | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.41 | |||||

| PHYtot | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.41 | ||||

| BOtot | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.27 | 0.32 | |||

| Support | −0.28 | −0.20 | −0.16 | −0.20 | −0.07 | −0.04 | ||

| Financ | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.24 | −0.08 | |

| Sex | 0.35 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.30 | −0.29 | 0.14 |

All correlations are significant, except that the correlations of Support with PHYtot and BOtot are not significant

TAtot subscale score trait anxiety, SAtot subscale score state anxiety, DEtot subscale score depressive symptoms, SOtot subscale score social problems, PHYtot subscale physical problems, BOtot subscale score body image, Financ question concerning financial problems, Sex problems with sexual life

In general, the results of the principle components analyses supported the one factor structure of each scale. With the exception of the scale trait anxiety, which had two factors (one method factor consisting of all recoded items), all scales showed to consist of one factor using the Eigenvalue >1 criterion, a criterion known to quickly overestimate the number of factors. The structure of the PDQ-BC was examined with confirmatory factor analysis. The model without allowing for any correlated error terms had a CFI of 0.87, a NNFI of 0.821, and a RMSEA of 0.116 (χ 2(27) = 82.19) To reach a better fit, the model required two correlations of two error terms (social problems with financial problems and social problems with physical problems) to reach a CFI of 0.93 (χ 2(25) = 54.3, p = 0.001; NNFI = 0.88; RMSEA = 0.088). This fit further is improved by adding another correlation between two error terms (body image with problems with sexual life) to reach a CFI of 0.95 (χ 2(24) = 43.3, p = 0.009; NNFI = 0.91; RMSEA = 0.073).

Reliability

The Cronbach’s alphas of the subscales trait anxiety, state anxiety, depressive symptoms, body image, social problems, and physical problems were 0.88, 0.85, 0.86, 0.79, 0.42, and 0.69, respectively.

Referral

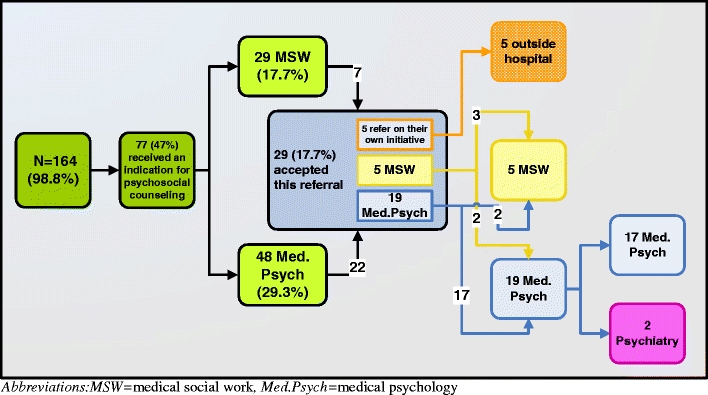

Figure 2 shows the percentage of patients receiving a referral advice. The scores of 77 patients (47%) indicated a referral for psychosocial counseling (i.e., 29 to medical social work and 48 to medical psychology). Of the latter group, five patients already had psychosocial therapy in a mental care setting outside the hospital. Twenty-nine patients (17.7%) agreed to be referred for social counseling, five to a medical social worker, 19 to a medical psychologist, and five to a professional outside the hospital. Two patients with a referral advice to medical psychology preferred medical social work. Two patients with a referral to a psychologist preferred medical social work. Also, two patients with a referral for medical psychologist were referred to a psychiatrist before they had any contact with a psychologist. Thus, of all participants, 14.6% was actually referred for psychosocial counseling within the hospital. Forty-eight (29.3%) with an advice for referral did not want to be referred because they have not (yet) experienced the need. Based on the discussions in the multidisciplinary meeting between health care professionals, it was concluded that all referrals based on the PDQ-BC were correctly made.

Fig. 2.

The percentage of patients receiving a referral advice. MSW medical social work, Med.Psych psychology

Acceptability of the PDQ-BC

One hundred and sixty-four patients completed the PDQ-BC. Only one patient was unable to fill in the screening instrument due to limited mental capacities. On average, patients indicated that they needed the 5-min range to complete the PDQ-BC.

Patients indicated that the PDQ-BC was easy to complete and the questions were perceived as relevant. They did not find it burdensome to complete the instrument, but found it normal that these topics were discussed.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop a short, easy-to-use psychosocial screening instrument specific for breast cancer patients (PDQ-BC) and to examine the acceptability, preliminary reliability, and validity of the PDQ-BC. In addition, this study examined whether the referral advice based on the PDQ-BC to the various psychosocial care providers was justified.

Apart from these primary goals, there are several benefits to develop a short and comprehensive, yet easy, screening tool. First, about 10% to 50% of the women with breast cancer suffer from psychosocial problems [4, 14–16]. The recent national guidelines state that psychosocial care for cancer patients is obligatory and screening measures should be implemented as part of the regular care of breast cancer patients. As such, patients with extended psychosocial problems can be identified and professional psychosocial support can be offered. Secondly, a brief questionnaire will be easy to incorporate into the regular care because it takes little time to complete and to score the results. Thus, a short screening tool can be completed several times during treatment and during the follow-up program without additional burden to patients and health professionals, making implementation more probable.

Patients indicated that the PDQ-BC was easy to complete and the questions were perceived as relevant. They did not find it burdensome to complete the instrument. Only one patient was unable to complete the screening instrument due to limited mental capacities.

The nurse practitioner experienced that the PDQ-BC was a good tool to systematically discuss a range of relevant psychosocial problems. In this way, no problem areas were neglected, and the nurse practitioner could spend attention solely on those areas in which patients experienced problem(s), which makes the discussion of these problems more patient-tailored and, thus, more efficient. The instrument facilitates a greater awareness of the concerns and needs for breast cancer patients during treatment and regular follow-up. Based on this experience, our findings underline the acceptability and usefulness of the PDQ-BC in clinical practice.

The PDQ-BC appears to have a good internal consistency. According to Cohen [47], internal consistency of a scale is considered good when it is above 0.70. Following this, the internal consistency of the most subscales was good. However, the subscale social problems had a much lower Cronbach’s alpha. There are two probable reasons why the alpha of the scale social problem is low. First, all scales with less than four questions will have an instable and often too low alpha. This is caused by the way an alpha is calculated. Second, the low alpha for social problems may be caused by the fact that each item was designed to tap into a different aspect of social problems (i.e., practical problems concerning family, practical problems with regard to work, and my medical situation/treatment has impaired me in my social functioning), which makes a high alpha less likely. This provides a broad picture of patients’ social problems. In addition, structural equation modeling showed that the structure of the PDQ-BC had a good fit.

The PDQ-BC assesses psychological risk factors (trait anxiety and lack of social support) and a range of problems in breast cancer patients in the adjuvant setting (social problems, physical problems, financial problems, body image, sexual problems, and demographic information). Forty-seven percent of patients were indicated for counseling. This prevalence of psychosocial problems was comparable with that reported in previous studies [4, 14–16]. In line with previous studies, we also found that not all patients with an increased level of these problems agreed to the suggested referral. This study showed similar rates of declination as compared with other studies [33].

Another screening instrument used in the Netherlands is the DT. This measure and the PDQ-BC are comparable concerning the percentage of patients that scored above the cut-off score. There are also several differences between both measures. One difference is that the PDQ-BC is tailored for breast cancer patients, thereby not including problems that are irrelevant for patients, such as difficulty with speaking as a physical dysfunction. The cut-off scores of the PDQ-BC concern specific aspects. Thus, the PDQ-BC provides cut-off scores for all nine scales. Moreover, the PDQ-BC has a differentiated outcome measure and not dichotomous (yes/no), which assesses the extent to which patients experience problems instead of a more undifferentiated yes/no response. Based on this information, the PDQ-BC results in a clear cut-off value for referral to the various specific psychosocial care providers. From the 164 patients, 77 patients (47%) have an indication for counseling, of whom 24 patients (31%) were actually referred: five patients to the medical social worker and 19 to the psychologist. Besides the care from the treating physician and nurse practitioner, most of the other patients refused referral except for five patients who preferred care from a social care provider outside the hospital.

More patients were referred to a psychologist than a social worker. An explanation could be that the PDQ-BC assesses risk factors for psychosocial problems. That is, an increased level of trait anxiety in combination with an increased level of state anxiety or depressive symptoms on the PDQ-BC is an indication for referral to a medical psychologist. Patients high on trait anxiety have a tendency to respond with a rise in anxiety in stressful situations and are at risk of experiencing, for instance, more fatigue [20] and a low QoL [20, 39]. These patients may benefit from psychotherapy [26, 48]. According to the health professionals, patients were correctly referred to medical social work or medical psychology.

It is conceivable that during the phase of treatment, the need for psychosocial support changes and as a result the rate of patients who seek referral also changes. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the referral information for psychosocial care across time. We do not yet have information on test–retest reliability and sensitivity to change. Future studies will need to focus on examining these features of the PDQ-BC as well as the sensitivity and specificity.

In conclusion, the PDQ-BC is developed with special attention to specific issues relevant for breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. It seems to be a useful instrument for selecting and referring those breast cancer patients who experience psychosocial problems and also seek to be referred. Patients who refrain from psychosocial care are monitored. The PDQ-BC is an easy-to-complete questionnaire and its psychometric properties are promising.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any conflict of interest that could inadvertently influence this work.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Benson JR, Jatoi I, Keisch M, Esteva FJ, Makris A, Jordan VC. Early breast cancer. Lancet. 2009;373(9673):1463–1479. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van de Velde CJH. Oncologie. 7. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenlee RT, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo PA. Cancer statistics, 2000. CA Cancer J Clin. 2000;50(1):7–33. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.50.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Somerset W, Stout SC, Miller AH, Musselman D. Breast cancer and depression. Oncology. 2004;18:1021–1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kissane DW, Clarke DM, Ikin J, Bloch S, Smith GC, Vitetta L, et al. Psychological morbidity and quality of life in Australian women with early-stage breast cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Med J Aust. 1998;169(4):192–196. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb140220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, Krupnick JL, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, et al. Quality of life at the end of primary treatment of breast cancer: first results from the moving beyond cancer randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(5):376–387. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schover LR. The impact of breast cancer on sexuality, body image, and intimate relationships. CA Cancer J Clin. 1991;41(2):112–120. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.41.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiebert GM, de Haes JC, Van de Velde CJH. The impact of breast-conserving treatment and mastectomy on the quality of life of early-stage breast cancer patients: a review. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9(6):1059–1070. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.6.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poulsen B, Graversen HP, Beckmann J, Blichert-Toft M. A comparative study of post-operative psychosocial function in women with primary operable breast cancer randomized to breast conservation therapy or mastectomy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1997;23(4):327–334. doi: 10.1016/S0748-7983(97)90804-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger AM, Higginbotham P. Correlates of fatigue during and following adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy: a pilot study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2000;27(9):1443–1448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(4):743–753. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimozuma K, Ganz PA, Petersen L, Hirji K. Quality of life in the first year after breast cancer surgery: rehabilitation needs and patterns of recovery. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;56(1):45–57. doi: 10.1023/A:1006214830854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arndt V, Merx H, Sturmer T, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H. Age-specific detriments to quality of life among breast cancer patients one year after diagnosis. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(5):673–680. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kornblith AB, Ligibel J. Psychosocial and sexual functioning of survivors of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2003;30(6):799–813. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall A, A'Hern R, Fallowfield L. Are we using appropriate self-report questionnaires for detecting anxiety and depression in women with early breast cancer? Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(98)00308-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, Graham J, Richards M, Ramirez A. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: five year observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330(7493):702. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38343.670868.D3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akechi T, Okuyama T, Imoto S, Yamawaki S, Uchitomi Y. Biomedical and psychosocial determinants of psychiatric morbidity among postoperative ambulatory breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;65(3):195–202. doi: 10.1023/A:1010661530585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newport DJ, Nemeroff CB. Assessment and treatment of depression in the cancer patient. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45(3):215–237. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(98)00011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. STAI manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (“self-evaluation questionnaire”) Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van der Steeg AF, De Vries J, van der Ent FW, Roukema JA. Personality predicts quality of life six months after the diagnosis and treatment of breast disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(2):678–685. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van der Steeg AF, De VJ, Roukema JA. Anxious personality and breast cancer: possible negative impact on quality of life after breast-conserving therapy. World J Surg. 2010;34:1453–1460. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0526-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Vries J, Van der Steeg AF, Roukema JA. Determinants of fatigue 6 and 12 months after surgery in women with early-stage breast cancer: a comparison with women with benign breast problems. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66(6):495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlsson M, Hamrin E. Psychological and psychosocial aspects of breast cancer and breast cancer treatment. A literature review. Cancer Nurs. 1994;17(5):418–428. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199410000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pusic A, Thompson TA, Kerrigan CL, Sargeant R, Slezak S, Chang BW, et al. Surgical options for the early-stage breast cancer: factors associated with patient choice and postoperative quality of life. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(5):1325–1333. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199910000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arving C, Sjoden PO, Bergh J, Hellbom M, Johansson B, Glimelius B, et al. Individual psychosocial support for breast cancer patients: a randomized study of nurse versus psychologist interventions and standard care. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30(3):E10–E19. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000270709.64790.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN practice guidelines for the management of psychosocial distress. Oncology (Willist. Park) 1999;13(5A):113–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheier MF, Helgeson VS, Schulz R, Colvin S, Berga S, Bridges MW, et al. Interventions to enhance physical and psychological functioning among younger women who are ending nonhormonal adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(19):4298–4311. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Cancer Control Programme (2004) NPK vision and summary. http://www.npknet.nl/share/files/4_901102/PDF%20file%20Engelse%20vertaling%20NPK.pdf

- 29.Health Council of The Netherlands(2009) Follow-up in oncology. Identify objectives, substantiate actions. http://www.gezondheidsraadnl/en/publications/follow-oncology-identify-objectives-substantiate-actions

- 30.Garssen B, De Kok E, Kruijver I, Kuiper B, Honing C, Visser A. Het gebruik van signaleringslijsten voor psychosociale problemen in de oncologie. TSG : tijdschrift voor gezondheidswetenschappen. 2009;86(5):269. doi: 10.1007/BF03082096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, Fleishman SB, Zabora J, Baker F, et al. Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2005;103(7):1494–1502. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tuinman MA, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, Hoekstra-Weebers JE. Screening and referral for psychosocial distress in oncologic practice: use of the Distress Thermometer. Cancer. 2008;113(4):870–878. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gil F, Grassi L, Travado L, Tomamichel M, Gonzalez JR. Use of distress and depression thermometers to measure psychosocial morbidity among southern European cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13(8):600–606. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0780-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hegel MT, Collins ED, Kearing S, Gillock KL, Moore CP, Ahles TA. Sensitivity and specificity of the Distress Thermometer for depression in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2008;17(6):556–560. doi: 10.1002/pon.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauwens S, Baillon C, Distelmans W, Theuns P. The ‘Distress Barometer’: validation of method of combining the Distress Thermometer with a rated complaint scale. Psychooncology. 2009;18(5):534–542. doi: 10.1002/pon.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell AJ. Pooled results from 38 analyses of the accuracy of distress thermometer and other ultra-short methods of detecting cancer-related mood disorders. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(29):4670–4681. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Vries J, Van Heck GL. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment Instrument (WHOQOL-100): validation study with the Dutch version. Eur J Psychol Assess. 1997;13(3):164–178. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.13.3.164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sprangers MA, Groenvold M, Arraras JI, Franklin J, Te Velde A, Muller M, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire module: first results from a three-country field study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(10):2756–2768. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.10.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.EORTC (2010) Modules—why do we need modules? http://groups.eortc.be/qol/questionnaires_modules.htm

- 42.Van der Steeg AF, Roukema JA, Ent FWC, Schriek MJ, Schreurs DMA, De Vries J. De invloed van dispositionele angst op de kwaliteit van leven van vrouwen met borstkanker—The influence of trait anxiety on quality of life in women with breast cancer. Gedrag & gezondheid : tijdschrift voor psychologie & gezondheid. 2006;34(4):223–236. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michielsen HJ, Van der Steeg AF, Roukema JA, De Vries J. Personality and fatigue in patients with benign or malignant breast disease. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(9):1067–1073. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marteau TM, Bekker H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Br J Clin Psychol. 1992;31(Pt 3):301–306. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1992.tb00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van der Bij AK, de WS C, RJ SEA, Braspenning JC. Validation of the Dutch short form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: considerations for usage in screening outcomes. Community Genet. 2003;6(2):84–87. doi: 10.1159/000073003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 2009;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Helgeson VS, Cohen S, Schulz R, Yasko J. Long-term effects of educational and peer discussion group interventions on adjustment to breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2001;20(5):387–392. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.20.5.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]