Abstract

Background:

Setting priorities is critical to ensure guidelines are relevant and acceptable to users, and that time, resources and expertise are used cost-effectively in their development. Stakeholder engagement and the use of an explicit procedure for developing recommendations are critical components in this process.

Methods:

We used a modified Delphi consensus process to select 20 high-priority conditions for guideline development. Canadian primary care practitioners who care for immigrants and refugees used criteria that emphasize inequities in health to identify clinical care gaps.

Results:

Nine infectious diseases were selected, as well as four mental health conditions, three maternal and child health issues, caries and periodontal disease, iron-deficiency anemia, diabetes and vision screening.

Interpretation:

Immigrant and refugee medicine covers the full spectrum of primary care, and although infectious disease continues to be an important area of concern, we are now seeing mental health and chronic diseases as key considerations for recently arriving immigrants and refugees.

Canada consistently receives more than 239 000 immigrants yearly, up to 35 000 of whom are refugees.1 Many arrive with similar or better self-reported health than the general Canadian population reports, a phenomenon described as the “healthy immigrant effect.”2–6 However, subgroups of immigrants, for example refugees, face health disparities and often a greater burden of infectious diseases.7,8 These health issues sometimes differ from the general population because of differing disease exposures, vulnerabilities, social determinants of health and access to health services before, during and after migration. Cultural and linguistic differences combined with lack of evidence-based guidelines can contribute to poor delivery of services.9,10

Community-based primary health care practitioners see most of the immigrants and refugees who arrive in Canada. This is not only because Canada’s health system centres on primary care practice, but also because people with lower socioeconomic status, language barriers and less familiarity with the system are much less likely to receive specialist care.11

Guideline development can be costly in terms of time, resources and expertise.12 Setting priorities is critical, particularly when dealing with complex situations and limited resources.13 There is no standard algorithm on who should and how they should determine top priorities for guidelines, although burden of illness, feasibility and economic considerations are all important.14 Stakeholder engagement to ensure relevance and acceptability, and the use of an explicit procedure for developing recommendations are critical in guideline development.15–17 We chose primary care practitioners, particularly those who care for immigrants and refugees, to help the guideline committee select conditions for clinical preventive guidelines for immigrants and refugees with a focus on the first five years of settlement.

Methods

We used a modified Delphi consensus process to select 20 high-priority conditions for guideline development.13,18,19 To begin, we identified key health conditions using an environmental scan, literature review and input from key informants from the Canadian Initiative to Optimize Preventive Care for Immigrants national network, a nascent network of immigrant health providers. This initial step identified 31 conditions. During the ranking process, survey participants were invited to list additional conditions. These conditions, if associated with potentially effective clinical preventive actions, were integrated into the pool of conditions for subsequent ranking.

We developed priority-setting criteria that emphasize addressing inequities in health, building on a process developed for primary care guidelines affecting disabled adults.13,20 Importance or burden of illness is often used for setting priorities; usefulness or effectiveness is frequently used; and disparity is now a well-recognized component of many public health measures.21 We defined our criteria as importance, usefulness and disparity:

Importance: conditions that are the most prevalent health issues for newly arriving immigrants and refugees. Conditions with a high burden of illness (e.g., morbidity and mortality).

Usefulness: conditions for which guidelines could be practically implemented and evaluated. These guidelines refer to health problems that are easy to detect, for which the means of prevention and care are readily available, are feasible, and for which health outcomes can be monitored.

Disparity: conditions that might not be currently addressed or are poorly addressed by public health initiatives or illness-prevention measures that target the general population.

We (HS, KP, MR, LN) purposively selected 45 primary care practitioners, including family physicians and nurse practitioners, recently or currently working in a setting serving recent immigrants and refugees. We sampled clinical settings from 14 urban centres across Canada to ensure in-depth experience with a variety of migrants. The settings also covered a range of health service funding models: community health centres/centres local de services communautaires, refugee clinics, group and solo practices, and ethnic community practices. We aimed to select practitioners with substantial experience, academic expertise or local leadership roles who were willing to commit to offering future input into guideline development and dissemination.

Immigrant and refugee health is a new subdiscipline. The skills, knowledge and experience that define expertise have not yet been determined; there are no examinations, certification or developed courses that can be used as a proxy for expertise. We believed contextual knowledge, experience that comes from engaged care of immigrants and refugees in Canada, and related international health work experience were important factors in determining expertise. As a measure for expertise, we adapted a formula used by Médecins Sans Frontières. This criterion combines work with Médecins Sans Frontières in developed countries and in the field. Our criterion for experience was set at seven years or more and includes all work in underdeveloped countries. It is calculated as: years of experience with migrants in Canada + two (years of experience working in underdeveloped countries).

As prompts for decision-making, we asked our practitioner panel to make choices based on the defined criteria, imagining that the guidelines under development might be used at a clinic serving new immigrants or by physicians who do not often see immigrant and refugee patients. Just as clinical practice does, these criteria challenged practitioners to make choices based on competing demands.

This first round of the Delphi survey aimed to ensure that we had the appropriate health conditions under consideration and to begin to develop some consensus as to priorities. Participants were asked to rank the 31 conditions identified initially and to propose conditions that were not on the initial list. We chose an a priori cut-off of 80% consensus for inclusion in the top 20. In the second round, we presented an unranked, modified version of this list, excluding all conditions that had already reached 80% consensus and adding newly proposed conditions. The remaining conditions to be included in the top 20 were determined by overall ranking in the second round. This list was reviewed by the codirectors of the Edmonton Multicultural Health Brokers Co-operative (www.mchb.org/OldWebsite2008/default.htm), a group representing over 16 ethnic communities that had initially requested preventive health guidance relevant for immigrant communities. In addition, the panel of experts who would be developing the guidelines reviewed the list. Following this, the final round requested approval through a simple agree/disagree vote of the process and the resulting list of priorities, with one-on-one interviews to resolve concerns in the two months following the ranking process.

Consent to participate in the Delphi survey was determined by completion of the questionnaire. Demographic questions elicited personal, professional and practice characteristics of the study participants. With each round, the participants were emailed an explanation of the process to date, the priority-setting criteria, instructions for filling out the survey and a link to the QuestionPro survey. Telephone follow-up was used to maximize response rate. We used Microsoft Excel for the analysis.

Results

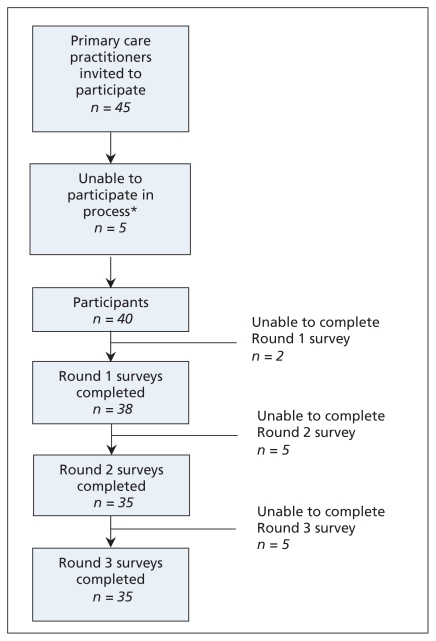

Ninety per cent (40/45) of the selected practitioners agreed to participate. Four of the five participants who chose not to participate cited reasons of leave of absence or sabbatical leave and the fifth cited workload. Ninety-five per cent of the consenting participants completed the first round of the survey; 88% completed the second and third (Figure 1). The first two rounds of the Delphi consensus process took place between Mar. 5 and May 31, 2007.

Figure 1:

Participant sampling and response rate. *One sabbatical, three leave of absence, one workload.

The 40 participants included 35 physicians and five nurse practitioners or nurses with expanded roles. Participants were predominantly women and had been in practice an average of 14 years. They worked an average of 16 hours per week with immigrants and refugees. More than 80% spoke two or more languages (Table 1).

Table 1:

Demographic characteristics of 40 participants in Delphi consensus process

| Characteristic | No. (%) of participants |

|---|---|

| Sex, female (n = 40) | 25 (62) |

| Age, yr, mean | 42.5 |

| Length of practice, yr, mean | 14.0 |

| Province of practice (n = 40) | |

| British Columbia | 7 (18) |

| Prairies (Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba) | 4 (10) |

| Ontario | 17 (42) |

| Quebec | 8 (20) |

| Maritime (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador) | 4 (10) |

| Type of practice (n = 39) | |

| Solo | 2 (5) |

| Group (excluding those in a community health centre) | 19 (49) |

| Community health centre | 18 (46) |

| Level of cross-cultural exposure and expertise | |

| Experience working with immigrants or refugees, yr, mean | 7.5 |

| Medical experience in low- and middle-income countries (n = 39) | 25 (64) |

| ≥ 7 years’ experience (criteria adapted from Médecins Sans Frontières) (n = 40) | 26 (65) |

| Bilingual (n = 40) | 33 (82) |

| Speaks more than two languages (n = 40) | 17 (42) |

The average length of experience working with refugees and immigrants in Canada was 7.5 years; 64% of participants had some experience working in underdeveloped countries, with a median overseas duration of 16 (range 1–120) months. Thirty-one per cent of primary care practitioners self-identified as being an immigrant or refugee; of the remainder, 38% self-identified as being the child of an immigrant or refugee (of 35 practitioners who responded to this optional question).

Forty-five per cent of participants identified themselves as having had prior training in the field — ranging from accredited tropical medicine courses, designated rotations during residency, work exposures before becoming a health care practitioner, conferences and self-directed studies in multicultural or cross-cultural medicine.

Refugees and immigrants came from all parts of the world for most practitioners; using an average of straight ranking (1–6) of regions, south and central Africa was estimated as the most frequent source region of immigrants for these practitioners. Children formed, on average, 30% of clientele, and women, 41%. Seventy-one per cent of migrants were estimated to have been in Canada less than five years; 73% were involuntary migrants. Involuntary migrants include refugee claimants and convention refugees and technically internally displaced persons (although this is not really an issue for Canada) (Table 2).

Table 2:

Region of origin for immigrants in practices of participants: average of straight ranking (1–6)

| Region of origin | Average rank |

|---|---|

| Africa (south and central) | 2.8 |

| Middle East and north Africa | 3.0 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 3.2 |

| South Asia | 3.7 |

| East Asia and Pacific | 4.4 |

| Europe and central Asia | 4.6 |

Box 1 lists the top 20 conditions for which practitioners identified a current need for guidelines on the basis of our criteria. In the first round, 80% consensus was reached to include 11 conditions. Eighty per cent consensus was also reached to exclude three conditions from the process: Chagas disease, colon cancer and prostate cancer. Three well-defined and unique conditions were proposed for the second round of ranking: osteoporosis, contraception and vision screening. The nine conditions selected in the second round were based on average ranking (Box 1).

Box 1: High-priority conditions.

Abuse and domestic violence*

Anxiety and adjustment disorder*

Cancer of the cervix

Contraception

Dental caries, periodontal diseases*

Depression*

Diabetes mellitus*

Hepatitis B*

Hepatitis C

HIV/AIDS*

Intestinal parasites*

Iron-deficiency anemia*

Malaria

Measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio and Hib disease

Pregnancy screening

Syphilis

Torture and post-traumatic stress disorder*

Tuberculosis*

Varicella (chicken pox)

Vision screening

Conditions identified by consensus in first round. (The rest were selected in the second round.)

The list of top 20 conditions was reviewed and approved with one modification by the panel of key experts who would be developing the guidelines: Routine vaccine-preventable diseases were considered a single priority, combining tetanus, diphtheria and polio (TdP) with measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) for guideline development. As a final step, survey participants were sent the identified 20 conditions for approval and discussion; 35/35 who participated in this round approved (88% of the 40 original participants).

Discussion

Refugees and many immigrants may have poor or deteriorating health, because of conditions experienced before, during or after arrival to Canada. A health care system that is poorly adapted to their needs compounds this situation, resulting in further marginalization. Our Delphi consensus process used practitioners’ years of field experience strategically to identify preventable and often unrecognized clinical care gaps that can result from such majority-system biases.

An overarching goal of our guideline development project is to supplement guidelines that exist for the general Canadian population22 by focusing on health inequities. We thus selected a high proportion of practitioners who work with refugees, a particularly vulnerable subgroup of immigrants prone to disparities. Using practitioners to select conditions ensured both that the needs of the future guideline users were given priority and that conditions presenting serious clinical challenges, but that might be under-represented in the literature, were included. In working with perceived needs of practitioners, we risked a reporting bias: overemphasizing popular stereotypes (e.g., the importance of infectious diseases); underemphasizing unrecognized or emerging conditions (e.g., vitamin D deficiency);23 and loss of precision in terms of specific populations (e.g., our list does not fully reflect the greatest needs of children).24 By deliberately selecting participants who work with refugees, we risked falsely stereotyping the health status of all immigrants by overemphasizing refugee-specific conditions and conversely by underemphasizing common heath risks, such as hypertension, that affect all immigrants.

The Delphi process selected 20 conditions for guideline development that reflect the needs and priorities of primary care practitioners working with immigrants and refugees. Although historically immigrant screening has focused on infectious diseases,25 the conditions selected by survey participants extend across a spectrum of diseases, including infectious disease, dentistry, nutrition, chronic disease, maternal and child health, and mental health. Mental health conditions were rated particularly high; all four of the proposed mental health conditions reached 80% consensus in the first round of the Delphi survey. Four infectious diseases and three chronic diseases also reached 80% consensus. The inclusion of dental caries and periodontal disease in the top 11 conditions is notable, reflecting important cultural, as well as socioeconomic, barriers that refugees and immigrants face in access to dental care.26 This range of conditions suggests that immigrant and refugee medicine covers the full spectrum of primary care; although infectious disease continues to be an important area of concern, we are now seeing mental health and chronic diseases as key considerations for recently arriving immigrants and refugees.

Conclusion

This evidence-based guideline initiative marks the evolution of immigrant and refugee medicine from a focus on infectious disease to a more inclusive consideration of such chronic diseases as mental illness, periodontal disease, diabetes and cancer. We used a practitioner-driven, equitable process to identify often-neglected conditions for which little evidence exists. There is very little published on the practitioners of immigrant and refugee medicine; the Delphi consensus process also provides a starting point for showing who these practitioners are and some of the knowledge and skills they possess. We hope this practitioner engagement process will improve the practicality of the evidence-based guidelines, will help practitioners who already work in the area target and streamline their efforts, and encourage new practitioners to enter this challenging and interesting discipline.

Key points

Preventable and treatable, but often-neglected, health conditions were selected for the development of guidelines for immigrant populations made vulnerable because of health system bias.

Criteria that emphasized addressing inequities in health helped identify gaps in clinical care.

Although infectious disease continues to be important, mental health and chronic diseases have emerged as areas of concern in the care of recently arriving immigrants and refugees.

Clinical preventive guidelines for newly arrived immigrants and refugees to Canada

This article is part of a series of guidelines for primary care practitioners who work with immigrants and refugees. The series was developed by the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the participation of the following practitioners: Jessica Audley (Toronto), Rolando Barrios (Vancouver), Denis Bedard (Québec), Glenn Campbell (Halifax), Juan Carlos Luis Chirgwin (Montréal), Tyler Curtis (Toronto), Gilles de Margerie (Montréal), Pierre Dongier (Montréal), Lynn Farrales (Vancouver), Susanne Fremming (Vancouver), Carol Geller (Ottawa), Doug Gruner (Ottawa), Reka Gustafson (Vancouver), Elisabeth Harvey (London), Susan Hoffman (Toronto), Lanice Jones (Calgary), Marie-Jo Ouimet (Montréal), Val Krinke (Edmonton), Kay Lee (Ottawa), Marie Munoz (Montréal), Bill Pegg (Toronto), Eva Purkey (Kingston), Leslie Rourke (St John’s), Millaray Sanchez (Ottawa), Kerry Telford (Vancouver), Patricia Topp (Ottawa), Gail Webber (Ottawa), Ed White (Charlottetown), Lise Loubert (Vancouver), Kathie McNally (Charlottetown), Angela Carol (Hamilton), Mike Dillon (Winnipeg).

Footnotes

Competing interests: Lavanya Narasiah received speaker fees from Glaxo-SmithKline for a travel health presentation. Peter Tugwell, chair of the CMA Journal Oversight Committee, is a coauthor of this article. He was not involved in the vetting of this article before publication. None declared for the other authors.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All authors contributed to conception and refinement of the study design and to analysis and interpretation of the data. Helena Swinkels drafted the initial manuscript, and all other authors provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final manuscript submitted for publication.

Funding: The Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health Steering Committee acknowledges the funding support of the Chronic Disease Branch of the Public Health Agency of Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Institute of Health Services and Policy Research), the Champlain Local Health Integration Networks, and the Calgary Refugee Program. The views expressed in this report are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders.

REFERENCES

- 1.Facts and figures: immigration overview permanent and temporary residents. Ottawa (ON): Citizenship and Immigration Canada; 2005. Cat. no. C&I-8113-06-06E [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen J, Ng E, Wilkins R. The health of Canada’s immigrants in 1994–95. Health Rep 1996;7:33–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng E, Wilkins R, Gendron F, et al. Dynamics of immigrants’ health in Canada: evidence from the National Population Health Survey. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunn JR, Dyck I. Social determinants of health in Canada’s immigrant population: results from the National Population Health Survey. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:1573–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newbold KB, Danforth J. Health status and Canada’s immigrant population. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:1981–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald JT, Kennedy S. Insights into the ‘healthy immigrant effect’: health status and health service use of immigrants to Canada. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1613–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DesMeules M, Gold J, Kazanjian A, et al. New approaches to immigrant health assessment. Can J Public Health 2004;95:I22–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beiser M. The health of immigrants and refugees in Canada. Can J Public Health 2005;96:S30–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beach MC, Gary TL, Price EG, et al. Improving health care quality for racial/ethnic minorities: a systematic review of the best evidence regarding provider and organization interventions. BMC Public Health 2006;6:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glazier RH, Bajcar J, Kennie NR, et al. A systematic review of interventions to improve diabetes care in socially disadvantaged populations. Diabetes Care 2006; 29:1675–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Doorslaer E, Masseria C, Koolman X. Inequalities in access to medical care by income in developed countries. CMAJ 2006;174:177–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schünemann HJ, Hill SR, Kakad M, et al. Transparent development of the WHO rapid advice guidelines. PLoS Med 2007;4:e119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oxman AD, Schunemann HJ, Fretheim A. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 2. Priority setting. Health Res Policy Syst 2006;4:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Battista RN, Hodge MJ. Setting priorities and selecting topics for clinical practice guidelines. CMAJ 1995;153:1233–7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AGREE Collaboration Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: the AGREE project. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:18–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schünemann H, Fretheim A, Oxman A. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 10. Integrating values and consumer involvement. Health Res Policy Syst 2006;4:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004;328:1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones J, Hunter D. Qualitative research: consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 1995;311:376–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loo R. The Delphi method: a powerful tool for strategic management. Int J Policy Strat Manage 2002;25:762–9 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sullivan WF, Heng J, Cameron D, et al. Consensus guidelines for primary health care of adults with developmental disabilities. Can Fam Physician 2006;52:1410–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Briss PA, Zasa S, Pappaioanou M, et al. Developing an evidence-based guide to community preventive services — methods. Am J Prev Med 2000;18:35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care Ottawa (ON); 2009. Available: www.canadiantaskforce.ca (accessed 2007 Sept. 25) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benson J, Skull S. Hiding from the sun — vitamin D deficiency in refugees. Aust Fam Physician 2007;36:355–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Canadian Paediatrics Society Children and youth new to Canada: a healthcare guide. Ottawa (ON): The Society; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gushulak BD, MacPherson DW. Population mobility and health: an overview of the relationships between movement and population health. J Travel Med 2004; 11:171–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selikowitz HS. Acknowledging cultural differences in the care of refugee and immigrants. Int Dent J 1994;44:59–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.