Abstract

Defective coupling between sarcoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria during control of intracellular Ca2+ signaling has been implicated in the progression of neuromuscular diseases. Our previous study showed that skeletal muscles derived from an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) mouse model displayed segmental loss of mitochondrial function that was coupled with elevated and uncontrolled sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release activity. The localized mitochondrial defect in the ALS muscle allows for examination of the mitochondrial contribution to Ca2+ removal during excitation-contraction coupling by comparing Ca2+ transients in regions with normal and defective mitochondria in the same muscle fiber. Here we show that Ca2+ transients elicited by membrane depolarization in fiber segments with defective mitochondria display an ∼10% increased amplitude. These regional differences in Ca2+ transients were abolished by the application of 1,2-bis(O-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, a fast Ca2+ chelator that reduces mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Using a mitochondria-targeted Ca2+ biosensor (mt11-YC3.6) expressed in ALS muscle fibers, we monitored the dynamic change of mitochondrial Ca2+ levels during voltage-induced Ca2+ release and detected a reduced Ca2+ uptake by mitochondria in the fiber segment with defective mitochondria, which mirrored the elevated Ca2+ transients in the cytosol. Our study constitutes a direct demonstration of the importance of mitochondria in shaping the cytosolic Ca2+ signaling in skeletal muscle during excitation-contraction coupling and establishes that malfunction of this mechanism may contribute to neuromuscular degeneration in ALS.

Keywords: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (Lou Gehrig's Disease), Calcium, Calcium Imaging, Mitochondria, Skeletal Muscle

Introduction

In skeletal muscle, mitochondria occupy 10–15% of the fiber volume and are located largely within the I-bands, surrounding the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR)2 network (1). This intimate juxtaposition of the SR and mitochondria, together with the ability of mitochondria to take up Ca2+ from their surroundings, results in movement of Ca2+ between these organelle systems (2–5). These movements are believed to help tailor mitochondrial metabolism and synthesis of ATP to the demand of muscle contraction (6). Reciprocally, Ca2+ flux into mitochondria could modify the Ca2+ transient that activates the muscle contractile proteins.

In non-muscle cells, mitochondria dynamically transport Ca2+ and modify Ca2+ flux into the endoplasmic reticulum, the nucleus, and across the plasma membrane to such an extent that they have been named “the hub of cellular Ca2+ signaling” (7). Evidence is mounting for a similar role for mitochondria in muscle cells; however, controversies remain regarding the quantitative aspects of Ca2+ transport between the SR and mitochondria (8, 9). Furthermore, little is known on the role of defective coupling between mitochondria and SR in control of intracellular Ca2+ signaling and how this contributes to pathological conditions in skeletal muscle.

Our recent study of skeletal muscle from a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) revealed localized mitochondrial defects involving loss of inner membrane potential that is linked to an elevated and poorly controlled intracellular Ca2+ release activity in the affected region (10). This ALS muscle presents a unique opportunity to quantify the contribution of mitochondria-mediated Ca2+ uptake in shaping the Ca2+ transients during excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling by comparing Ca2+ transients in regions with normal or defective mitochondria in the same muscle fiber. In this study, we present evidence that mitochondria can buffer up to 10–18% of the Ca2+ released from the SR during E-C coupling. Using a combination of pharmacological and molecular biosensor approaches, we demonstrate that a deficit in mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is a major cause for the elevated and uncontrolled Ca2+ transients in ALS muscle fibers during voltage-induced Ca2+ release. Because these mitochondrial defects were largely localized to the neuromuscular junction, our data suggest that changes in mitochondrial control of Ca2+ signaling could be linked to the activity-dependent progression of muscle atrophy in ALS.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Muscle Fiber Preparation

Normal and G93A3 mice (11) at the age of 2–3 months were used in this study. Protocols on usage of mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Rush University. Individual muscle fibers were isolated from these mice following the protocols of Refs. 12 and 10. Briefly, flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscles were digested in modified Krebs solution (0 Ca2+) plus 0.2% type I collagenase for 55 min at 37 °C. Following collagenase treatment, fibers were stored in an enzyme-free Krebs solution at 4 °C and used for functional studies within 36 h.

Constructing pcDNA3/mt11-YC3.6

The plasmid pcDNA3/YC3.6 (13) was used to construct pcDNA3/mt11-YC3.6. The mitochondrial targeting sequence consists of 11 amino acids (LSLRQSIRFFK) of cytochrome oxidase subunit IV (14). The corresponding cDNA of this mitochondrial targeting sequence was synthesized by Invitrogen and fused to the 5′ end of YC3.6 using the restriction enzyme HindIII. The final construct was verified by DNA sequencing.

Electroporation and Gene Expression in FDB Muscle of Adult Mice

The protocol was modified from Refs. 15 and 16. The anesthetized mice were injected with 10 μl of 2 mg/ml hyaluronidase dissolved in sterile saline at the ventral side of the hind paws through a 29-gauge needle. 1 h later, 5–10 μg of plasmid DNA of pCDNA3/mt11-YC3.6 in 10 μl of sterile saline were injected into the same sites. 15 min later, two electrodes (gold-plated stainless steel acupuncture needles) were placed at the starting lines of paw and toes, separated ∼9 mm. 20 pulses of 100 V/cm and 20 ms were applied at 1 Hz (ECM 830 Electro Square Porator, BTX Harvard Apparatus). 7–14 days later, the animal was euthanized by CO2 inhalation, and FDB muscles were removed for imaging or functional studies.

Fluorescence Dye Loading and Confocal Microscopic Imaging

FDB muscle fibers were incubated with 50 nm TMRE for 10 min at 25 °C for visualization of mitochondrial inner membrane potential (ΔΨ). For simultaneous monitoring of mitochondria and the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) of the FDB muscle fibers, 1.5 mg/ml α-bungarotoxin (bungarotoxin conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647) was added to the cell culture dish with TMRE at the same time. Fluo-4 AM, fluo-4, or x-rhod-1 was used to monitor intracellular Ca2+ at various conditions. The YC3.6 protein functions as a ratiometric Ca2+ probe (13) because its fluorescence changes in opposite directions at two wavelengths in response to a change of [Ca2+]. mt11-YC3.6 was expressed in muscle fibers for monitoring mitochondrial Ca2+. Separated excitation and emission wavelengths were applied for simultaneous recording of cytosolic Ca2+ (x-rhod-1). x-rhod-1 was excited at 594 nm, and its fluorescence was collected at 600–680 nm, whereas mt11-YC3.6 was excited at 458 nm, and its fluorescence F1 was collected at 470–520 nm and F2 at 520–580 nm. For simultaneous recording of the fluorescence of fluo-4 and TMRE, fluo-4 was excited at 488 nm with the fluorescence collected at 490–540 nm, whereas TMRE was excited at 543 nm with the fluorescence collected and at 560–620 nm. A confocal microscope capable of line-interleaving images excited with different lasers (SP2-AOBS, Leica Microsystems, Germany) with a 63×, 1.2 NA water immersion objective was used. Chemicals were purchased from Sigma, and fluorescent dyes were purchased from Invitrogen.

Live Cell Imaging of Osmotic Shock-induced Local Ca2+ Release in FDB Muscle Fibers

G93A FDB muscle fibers were first incubated with 3 μm fluo-4 AM for 60 min and then with 50 nm TMRE for 10 min at 25 °C. Muscle fibers loaded with the indicators in Krebs solution were exposed to a 170 mosm hypotonic solution containing (in mm) 64 NaCl, 5 KCl, 10 Hepes, 10 glucose, 2.5 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, pH 7.2, for 2 min and then returned to Krebs solution. Ca2+ signals were monitored before, during, and after the osmotic shock following the protocol of Ref. 10.

Voltage Clamp of FDB Muscle Fibers

G93A fibers were first incubated with 50 nm TMRE for 10 min to select fibers with regionally defective mitochondria. Cells with depolarized mitochondria were patched with 0.6–1.0-megaohm pipettes filled with a cesium glutamate-based solution containing: 120 mm cesium glutamate, 10 mm EGTA (5 or 15 mm BAPTA in different cases as indicated under “Results”), 10 mm glucose, 10 mm Tris base, 5 mm ATP, 10 mm phosphocreatine, 1 mm Mg2+, 100 nm Ca2+, and 50 μm fluo-4. An Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) was used for whole-cell patch clamp. The fiber was clamped at −80 mV, and changes in cytosolic Ca2+ transients were recorded following application of depolarizing voltages. The external solution contained 140 mm triethanolamine CH3SO3H, 10 mm Hepes, 1 mm CaCl2, 3.5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm 4-aminopyridine, 0.3 mm LaCl3, 0.5 mm CdCl2, 0.5 μm tetrodotoxin, and 50 μm N-benzyl-p-toluenesulfonamide. The method was modified from our previous study (16). In the case of voltage-clamping FDB fibers with expression of mt11-YC3.6, 50 μm x-rhod-1 was included in the pipette solution for simultaneous recording of cytosolic changes of Ca2+.

Image Processing and Data Analysis

IDL 7.0 (ITT Visual Information Solutions) was used for image processing. SigmaPlot 11.0 and Microsoft Excel were used for data analysis. Data were represented as mean ± S.E. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t test.

RESULTS

Voltage-induced Ca2+ Transients Are Elevated at the Neuromuscular Junction Region with Defective Mitochondria in G93A Muscle Fibers

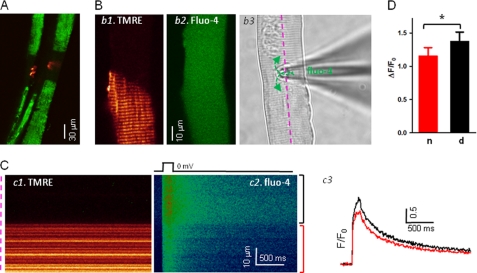

FDB muscle fibers isolated from the ALS transgenic mouse model harboring the G93A mutation were stained with both TMRE (a probe for monitoring mitochondrial inner membrane potential) and α-bungarotoxin (a ligand of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in postsynaptic membranes of the NMJ). Fig. 1A shows an example with overlay of TMRE (green) and α-bungarotoxin (red) fluorescence in G93A fibers, where reduced staining with TMRE corresponds to defective mitochondria that overlap with the area near the NMJ. In multiple preparations, we frequently observed that defective mitochondria were largely localized to the NMJ region (10).

FIGURE 1.

Voltage-induced Ca2+ transients are elevated at the NMJ region with defective mitochondria in ALS muscle fiber. A, simultaneous imaging of mitochondrial function (TMRE, green) and the NMJ area (α-bungarotoxin, red) of G93A fibers. Note that the fiber segments with depolarized mitochondria are overlapped with the NMJ area. B, voltage clamp configuration. G93A fibers were first loaded with TMRE to identify the fiber segment with depolarized mitochondria (panel b1). The patch pipette was placed at the interface of the regions with or without TMRE staining (panel b3). fluo-4 diffused into the fiber through the pipette (panel b2). C, simultaneously recorded xt line scan images of TMRE (panel c1) and fluo-4 fluorescence (panel c2) during a depolarizing pulse. The pipette solution contained 10 mm EGTA. Panel c3, Ca2+ transients reported by normalized fluo-4 fluorescence changes (F/F0), in the region with normal mitochondria (red), and in the region with depolarized mitochondria (black). Note the elevated Ca2+ transients in the area with defective mitochondria. D, averaged ΔF/F0 in the fiber region with or without defective mitochondria. n, fiber segments with normal mitochondria; d, fiber segments with depolarized mitochondria. *, p < 0.001.

Based on the staining pattern of TMRE (Fig. 1B, panel b1), a patch pipette was placed at the interface between the fiber segments containing normal or defective mitochondria (Fig. 1B, panel b3). This configuration limited potential errors in detection of Ca2+ transients between those two segments due to possible uneven voltage clamping along the fiber during membrane depolarization. Near-uniform distribution of the fluo-4 Ca2+ indicator could be achieved throughout the muscle fiber 15–20 min after successful formation of a gigaohm seal (Fig. 1B, panel b2). Line scan (xt) images of TMRE (Fig. 1C, panel c1) and fluo-4 (panel c2) were simultaneously recorded along the fiber (panel b3, pink line) when a depolarization pulse was applied. The TMRE image distinguishes the fiber segment with defective mitochondria (Fig. 1C, black bracket) from the segment with normal mitochondria (red bracket). Normalized fluorescence traces (F/F0) for the two fiber regions were then derived from the line scan images of fluo-4 (Fig. 1C, panel c2). Clearly, the fiber segment with depolarized mitochondria had a greater fluorescence increase (panel c3, black trace) in response to a membrane depolarization when compared with the region in the same fiber containing normal mitochondria (red trace). On average, a 10.1 ± 1.7% increase in the peak fluorescence of fluo-4 was measured in fiber segments with defective mitochondria (n = 8 fibers from six G93A mice, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1D).

Inhibition of the Mitochondrial Uniporter Promotes Propagation of Ca2+ Events beyond the Defective Mitochondrial Region

Mitochondria maintain a large negative inner membrane potential (ΔΨ = ∼−180 mV) that provides the driving force for Ca2+ uptake into the mitochondria. ALS muscle with reduced ΔΨ should in principle have reduced capacity to buffer cytosolic Ca2+.

Ru360 has been shown to be a potent blocker of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (mCU) (17, 18). To test whether direct inhibition of mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter can affect the intracellular Ca2+ release activity, Ru360 was applied to the G93A muscle fiber in which the Ca2+ release events were first induced by osmotic shock. Osmotic stress-induced Ca2+ activity has been previously established as an index for the integrity of the intracellular Ca2+ release machinery of skeletal muscle cells (10, 12, 19, 20).

As shown in Fig. 2, G93A muscle fibers were dually loaded with TMRE and fluo-4 AM. TMRE staining identified the G93A fibers with mitochondrial defects (Fig. 2, panel 1). In the resting condition, skeletal muscle fibers from wild type or G93A mice show few spontaneous Ca2+ sparks (10, 12, 19–21). Brief exposure of muscle fibers to hypotonic solution caused cell swelling and frequent Ca2+ release events upon return to isotonic solution. As observed in our previous study (10), the G93A muscle fiber displays osmotic stress-induced Ca2+ sparks specifically within the area of defective TMRE labeling (Fig. 2, panels 2 and 3). Application of 20 μm Ru360 in the external solution caused an immediate increase in Ca2+ release activity that propagated beyond the region with defective mitochondria. The data shown in Fig. 2 were representative of four experiments. Thus, pharmacological inhibition of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake exacerbates the osmotic stress-induced Ca2+ response and allows for propagation of Ca2+ release activity beyond the region with defective mitochondria in ALS muscle.

FIGURE 2.

Ru360 promotes propagation of stress-induced Ca2+ release events beyond the defective mitochondrial region. The G93A fiber was loaded with both TMRE (panel 1) and fluo-4 AM (panels 2-5). Following a brief (2-min) hypotonic shock, the stress-induced Ca2+ release events stay mainly in the fiber segment with depolarized mitochondria (panels 2 and 3). Perfusion of Ru360, an inhibitor of mitochondrial uniporter, caused propagation of those osmotic stress-induced Ca2+ release events beyond the defective mitochondrial region (panels 4 and 5).

Using mt11-YC3.6 to Evaluate the Dynamic Change of Ca2+ inside Mitochondria

Although our studies illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2 indicate that a deficit in mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake can contribute to elevated and uncontrolled Ca2+ response during E-C coupling, an important and yet unanswered question is whether mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is altered in G93A muscle fibers during the rapid phase of Ca2+ release from the SR. Addressing this question requires direct monitoring of the dynamic change of Ca2+ inside mitochondria.

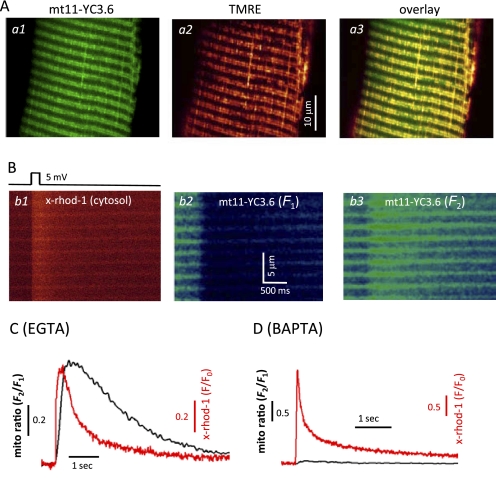

Previous studies used rhod-2 AM to monitor [Ca2+] inside mitochondria in various cell types (22–25). Interpretation of rhod-2 results in intact cells can be difficult because a portion of the dye remains in the cytosol or enters other organelles. In skeletal muscle, it is even harder to distinguish the signal of mitochondria from that of the SR as both organelles are spatially intertwined (26). Recently, organelle-targeted Ca2+ biosensors have been developed to directly monitor Ca2+ inside the SR or mitochondria in skeletal muscle fibers (27, 28). We utilized the biosensor protein YC3.6, which displays an improved dynamic range (13) when compared with the earlier version (YC2) (28).

By adding a mitochondrial targeting sequence (14) to the C terminus of the cDNA of YC3.6, we constructed a mitochondrion-targeted biosensor named mt11-YC3.6. We first tested this new construct expressed in FDB skeletal muscle in wild-type mice. 2 weeks after injection of the plasmid, the transfected FDB muscle fibers showed mt11-YC3.6 in a mitochondrial expression pattern (Fig. 3A, panel a1) as co-staining with TMRE (panel a2) revealed an overlapping pattern with mt11-YC3.6 fluorescence (panel a3). We next performed voltage clamp experiments to simultaneously measure changes in cytosolic [Ca2+] and mitochondrial [Ca2+] during a brief membrane depolarization (Fig. 3B). The patch pipette solution contained x-rhod-1, a fast cytosolic Ca2+ indicator with excitation and emission spectra distinct from those of mt11-YC3.6. Application of a depolarizing pulse induced Ca2+ release from the SR measured as an increase in the fluorescence of x-rhod-1 (Fig. 3B, panel b1). The YC3.6 protein functions as a ratiometric Ca2+ probe (13) because its fluorescence changes in opposite directions at two wavelengths (F1 and F2) as shown in Fig. 3B, panels b2 and b3, in response to Ca2+ release from the SR. The calculated ratio of F2/F1 (mito ratio) indicates an increase in [Ca2+] inside mitochondria upon voltage-induced Ca2+ release (Fig. 3C). To confirm that the changes of mt11-YC3.6 fluorescence are a quantitative indication of mitochondrial [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]mito), we replaced 5 mm EGTA with 5 mm BAPTA inside the pipette solution. BAPTA, a fast Ca2+ chelator, has been used to suppress mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (25, 29). Indeed, application of 5 mm BAPTA dramatically reduced the signal of mt11-YC3.6 during a voltage-induced Ca2+ release event, indicating that the signal of mt11-YC3.6 emanates from mitochondria. A representative experiment is shown in Fig. 3D.

FIGURE 3.

Measurement of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake using mt11-YC3. 6 biosensor. A, a live muscle fiber expressing mt11-YC3.6 (panel a1) was also incubated with TMRE (panel a2). The overlay (panel a3) shows that mt11-YC3.6 targeted to mitochondria very well. The expression of this biosensor does not change the mitochondrial membrane potential. B, simultaneous recording of cytosolic Ca2+ transient (panel b1) and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (panels b2 and b3) during a voltage-induced Ca2+ release. The experiment was done with 5 mm EGTA inside the pipette solution. C, plot of the cytosolic Ca2+ transient presented by the fluorescence change (F/F0) of x-rhod-1 from panel b1 and the change of the mito ratio (F2/F1) of mt11-YC3.6 from panels b3 and b2, which represents the corresponding dynamic change of Ca2+ inside mitochondria during voltage-induced Ca2+ release. D, replacing 5 mm EGTA with 5 mm BAPTA inside the pipette solution dramatically reduced the signal of mt11-YC3.6, indicating that mito ratio in C indeed is an indication of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. A 20-mV 50-ms depolarization pulse was applied to induce the Ca2+ release.

Mitochondrial Ca2+ Uptake Affects Voltage-induced Ca2+ Transients

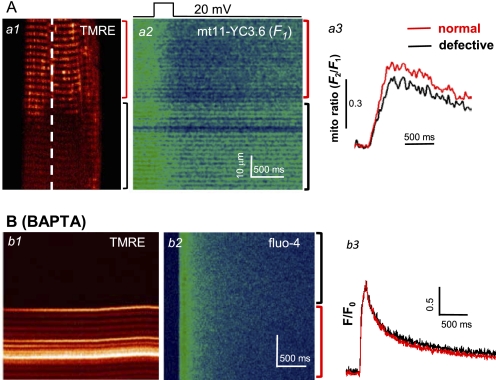

Using mt11-YC3.6 to measure [Ca2+]mito, we were able to directly test whether defective mitochondria in G93A muscle fibers have reduced capacity to take up Ca2+ during E-C coupling. First, the mt11-YC3.6 expression plasmid was electroporated into the FDB muscles of G93A mice. Isolated FDB fibers were voltage-clamped with the patch pipette placed at the boundary of the normal and defective regions, based on TMRE staining (Fig. 4A). Following a brief membrane depolarization, the fluorescence images F1 and F2 of mt11-YC3.6 were recorded. A representative image of F1 is shown in Fig. 4A, panel a2. Clearly, the fiber segment with defective mitochondria (black bracket) displayed a reduced fluorescence change in response to membrane depolarization when compared with the region in the same fiber containing normal mitochondria (red bracket). The calculated mito ratio (F2/F1) is shown in panel a3. On average, a 14.6 ± 1.9% decrease of the maximum change of mito ratio was measured in fiber segments with defective mitochondria (n = 4 fibers from two G93A mice, p = 0.002). The reduced mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (Fig. 4A, panel a3, black trace) mirrors the increased cytosolic Ca2+ transient observed in the defective fiber region of the G93A muscle cell (Fig. 1C). These data suggest that the increased Ca2+ transient in the defective fiber region is due to a reduced Ca2+ removal by defective mitochondria in this region.

FIGURE 4.

Deficit in mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake elevates the voltage-induced Ca2+ transients in ALS skeletal muscle. A, panel a1, a G93A muscle fiber expressing mt11-YC3.6 was loaded with TMRE to distinguish the normal fiber region (red bracket) from the defective region (black bracket). Panel a2, the same fiber was voltage-clamped, and xt line scan signal for mt11-YC3.6 was recorded along the dashed line in panel a1 during a membrane depolarization pulse. F1 of mt11-YC3.6 signal was shown in the figure. Panel a3, the calculated mito ratio (F2/F1) in both normal (red) and defective (black) regions. Note the reduced mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in the fiber region with depolarized mitochondria. B, simultaneously recorded line scan images of TMRE (panel b1) and fluo-4 (panel b2) of a G93A fiber during a depolarizing pulse when the pipette solution contained 15 mm BAPTA. Note that intracellular BAPTA, a fast Ca2+ chelator that is known to reduce mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, diminished the difference in the Ca2+ transients in normal and defective regions (panel b3).

We next tested whether suppressing mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake could eliminate the difference in Ca2+ transients between the normal and defective regions during voltage-induced Ca2+ release. For this purpose, we included BAPTA inside the pipette solution at a high concentration (15 mm). Fig. 4B shows a representative line scan image and derived F/F0 of a G93A muscle fiber during voltage-induced Ca2+ release in the presence of BAPTA. Clearly, under this condition, there were no significant differences in Ca2+ transients between the normal and defective regions recorded from seven fibers derived from three different G93A mice. Averaged F/F0 is 1.78 ± 0.39 in the region with normal mitochondria and 1.79 ± 0.39 in the defective region (p = 0.943). Thus, a smaller Ca2+ transient in the normal region recorded in the presence of EGTA is likely due to Ca2+ removal by mitochondria, a phenomenon that appears to be reduced in the region containing defective mitochondria.

Calculation of Mitochondrial Contribution to Ca2+ Removal during Voltage-induced Ca2+ Release

For quantitative assessment of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake associated with voltage-induced Ca2+ release in skeletal muscle, the following analyses were performed. First, dynamic changes of intracellular free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]cyto(t)) were derived from the fluorescence intensity F(t) of fluo-4 (as shown in Fig. 1C, panel c3) using the formula previously established in Refs. 16 and 30, with parameters of koff fluo-4 = 0.08 ms−1 (31); F0 is the average value of F(t) during times before the pulse, and [Ca2+]cyto(0) = 100 nm, the free [Ca2+] inside the solution of patching pipette. Calculated Ca2+ transients in both normal and defective segments in a representative G93A fiber are shown in Fig. 5A. Averaged data show that the peak Ca2+ transient in the defective mitochondria region is 15.6 ± 2.9% larger than that in the normal mitochondria region (n = 8, p < 0.05).

FIGURE 5.

Quantitative assessment of mitochondrial contribution on Ca2+ removal during voltage-induced Ca2+ release. A, dynamic changes of cytosolic [Ca2+] derived from fluorescence changes in the region with normally polarized mitochondria (red trace), and in the region with depolarized mitochondria (black trace) using the method described in Ref. 30. B, Ca2+ release fluxes derived from Ca2+ transients as shown in A by applying the removal method (34). The parameters used are koff-fluo-4 = 0.09 ms−1, kon-egta = 0.015 (μm,ms)−1, koff-egta = 0.0075 ms−1, and SR pump rate kuptake = 11 ms (32–34). Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake flux (green trace in B) was derived by calculating the difference of fluxes between defective and normal regions. C, comparing the kinetics of increased cytosolic Ca2+ transient (Δ[Ca2+]cyto, black trace) in the defective region and the mitochondrial Ca2+ change ([Ca2+]mito, red trace) in the normal fiber region. [Ca2+]mito was calculated by applying the modified method (35). Note the similar time course of those two.

To assess the magnitude of Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria, we adapted the Ca2+ release flux calculations developed in Ref. 32 that were modified in Refs. 33 and 34. The Ca2+ release flux can be described by the following equation

where the removal flux contains two terms: buffering by EGTA and the uptake of Ca2+ into the SR by the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) pump. Fig. 5B shows calculated Ca2+ release fluxes in the defective region (black trace), which is larger than that in the normal region (red trace). However, there is no reason to believe that the release flux is actually different in the two regions as when the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake was blocked by intracellular application of BAPTA, the Ca2+ transients at both normal and defective regions were identical (Fig. 4B). Thus, the SR Ca2+ release machinery is likely to be similar in all regions of a particular G93A muscle fiber. Considering that this original calculation of flux did not include the removal of Ca2+ by mitochondria, the difference in calculated release flux (Fig. 5B, green trace) is in principle attributable to the removal by mitochondria in the normal fiber region. Averaged mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in the normal region contributes to 18.6 ± 2.4% (n = 8, p < 0.05) of the total Ca2+ removal at the peak during voltage-induced Ca2+ release. The averaged mitochondrial Ca2+ influx is 4.1 ± 1.0 μm/ms at the peak Ca2+ release (n = 8).

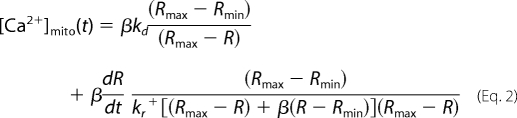

Unless Ca2+ buffering is very non-linear, the increase in the Ca2+ transient in the defective fiber region should mirror kinetically the Ca2+ removal by mitochondria in the normal region. We tested the prediction by comparing the kinetics of the increased Ca2+ transient in the defective fiber region (Δ[Ca2+]cyto) and the dynamic change of mitochondrial Ca2+ ([Ca2+]mito) in the normal region. Δ[Ca2+]cyto (Fig. 5C, black trace) was calculated by subtracting the Ca2+ transient in the normal region from the one in the defective region of a G93A muscle fiber. [Ca2+]mito in the normal fiber region of a G93A fiber expressing mt11-YC3.6 was calculated from the mito ratio (R) change by using the standard formula established by Grynkiewicz et al. (35) with kinetic correction

|

in which, β = 4.1 (F1 at 0 Ca2+/F1 at saturated Ca2+), Rmax = 5.2, Rmin = 0.9 (in situ calibration of mt11-YC3.6 expressed in skeletal muscle fibers), kd = 0.25 μm (13), kr+ = 0.02 mm−1, ms−1 (36). As shown in Fig. 5C, Δ[Ca2+]cyto in the defective fiber region and the dynamic change of [Ca2+]mito at the normal fiber region have similar kinetics, although they are not identical. This difference may be explained by an imperfect calibration or buffer non-linearity. Taken as a whole, our analysis of the data supports that a reduced capacity of mitochondria to buffer Ca2+ is a major cause of the increased Ca2+ transients during voltage-induced Ca2+ release in fiber regions containing defective mitochondria in ALS skeletal muscle.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that mitochondria rapidly capture Ca2+ to shape the intracellular Ca2+ transients in skeletal muscle during E-C coupling. Using voltage clamp measurements, we found that muscle fiber segments with defective mitochondria showed elevated Ca2+ transients due to reduced mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in the G93A muscle fibers. Interference with mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake by either Ru360 or BAPTA could influence the intracellular Ca2+ transient during E-C coupling. As the fiber region with defective mitochondria always includes the muscle side of NMJ, our data demonstrate that a deficit in mitochondrial participation during intracellular Ca2+ signaling may contribute to degeneration of the ALS muscle.

The mechanism of mitochondrial controlling of intracellular Ca2+ signals in various cell types has been extensively studied (see reviews in Refs. 2, 4, and 5). Due to the central role of mitochondria in controlling cell metabolism and cell death, many studies have been conducted in cardiac muscle to examine the role of mitochondria in shaping cytosolic Ca2+ transients in both physiological and pathophysiological conditions (23, 37–40). Fewer studies have been done in skeletal muscle research. Although several studies have suggested a role for mitochondria in control of Ca2+ signaling in skeletal muscle (25, 28, 41), we, for the first time, show that mitochondria can shape rapid Ca2+ transients during voltage-induced Ca2+ release from the SR.

Although our data support the idea that compromised mitochondrial function could be a principal factor contributing to the augmented Ca2+ release activity in the ALS muscle, it is also possible that the enhanced Ca2+ transient includes contributions from increased SR Ca2+ release in the defective fiber segment due to a greater activity of ryanodine receptor/Ca2+ release channels (RyR). It is known that the activity of the ryanodine receptor channel can be modified by reactive oxygen and/or nitrogen species (20, 42–45). The depolarized mitochondria in the defective fiber segment may have modified the status of the local release channels. At this point, we cannot biochemically separate the release channels from the different segments of muscle fibers or directly test the activity of the release channels in the different fiber segments in vivo. However, we tested our hypothesis by using BAPTA at a high concentration to block mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in the normal fiber segment in our voltage clamp experiments. If mitochondria function as an additional buffer for Ca2+ release from the SR, application of BAPTA, a fast Ca2+ chelator, should reduce Ca2+ uptake by mitochondria in the normal fiber segment. Thus, Ca2+ transients derived from both normal and defective fiber segments should be similar in the presence of BAPTA, as we observed in Fig. 4B. These results suggest that the function of Ca2+ release machinery is comparable in all regions of a given G93A muscle fiber. Thus, our data support the hypothesis that loss of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is a major cause of the enhanced Ca2+ transients observed in the segment of G93A muscle fibers displaying defective mitochondria.

Quantitative measurement of mitochondrial Ca2+ in intact skeletal muscle cells is challenging as the commercially available fluorescent dye for such applications, i.e. rhod-2 AM, is not a ratiometric dye and does not specifically target to mitochondria. Organelle-targeted ratiometric Ca2+ biosensors are a better choice. With expression of a mitochondrion-targeted biosensor (2mtYC2) in muscle, Rudolf et al. (28) demonstrated that [Ca2+]mito could measurably increase in a single twitch. This earlier version of the biosensor had a small dynamic range with a maximal 20% increase of emission ratio when calibrated in the cytosol during a tetanic stimulation. In these studies, we used an improved biosensor YC3.6 with a dynamic range around 6 (in vitro calibration) (13). Our in situ calibration of mt11-YC3.6 showed a similar dynamic range (Rmax/Rmin = 5.7) in muscle cells. We demonstrate that mt11-YC3.6 is an improved mitochondrial Ca2+ sensor, which can be used to evaluate the dynamic changes of [Ca2+]mito under physiological conditions. To our knowledge, this is the first time that mitochondrial Ca2+ levels were directly recorded in skeletal muscle under voltage clamp configuration. By expressing mt11-YC3.6 in G93A skeletal muscle, we detected a reduced mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in the fiber region with defective mitochondria during a voltage-induced Ca2+ release. This reduced mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in the defective fiber region mirrors the elevated Ca2+ transients in the same area (Fig. 5C). Thus, a reduced capacity of mitochondria to capture Ca2+ during muscle contraction is responsible for the elevated Ca2+ signaling in G93A skeletal muscle. As the areas of defective mitochondria always face the NMJ, the deficit in mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and consequent increase in Ca2+ transients may contribute to the neuromuscular degeneration in the progression of ALS.

By comparing the Ca2+ transients and mitochondrial Ca2+ influxes in fiber regions with normal or defective mitochondrial function, we evaluated the contribution of mitochondria to buffer Ca2+ during voltage-induced Ca2+ release. The estimated contribution of mitochondria to Ca2+ removal amounts to a range of 10–18% at the peak release, which is not inconsistent with the study by Pacher et al. (22) who showed that in cardiac muscle, mitochondria can buffer up to 26% of intracellular Ca2+ released from the SR. The smaller uptake of mitochondria may well be due to lesser total mitochondrial volume in skeletal muscle (46). In addition, mitochondria in the fiber region marked by reduced fluorescence of TMRE may not be completely depolarized and may still reserve some ability to accumulate Ca2+. As shown in Fig. 4A, the G93A muscle fiber expressing mt11-YC3.6 showed Ca2+ uptake by mitochondria in the defective region. Thus, it is possible that total mitochondrial Ca2+ removal in skeletal muscle may be underestimated in our experimental conditions.

In summary, our results provide direct evidence that mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake can modulate rapid Ca2+ transients associated with E-C coupling. The contribution of mitochondria to Ca2+ removal amounts to a range of 10–18% at the peak release in skeletal muscle under our experimental conditions. This sizable contribution to intracellular Ca2+ handling may play an important role in muscle physiology. Consequently, disruption of mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering should be an important component of the pathophysiology of neuromuscular diseases such as ALS.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. A. Miyawaki (RIKEN Brain Science Institute, Japan) and Dr. N. Demaurex (University of Geneva, Switzerland) for providing plasmid YC3.6 and Dr. R. T. Dirksen (University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry) for valuable discussions on this manuscript.

This work was fully supported by Muscular Dystrophy Association Grant MDA-4351 and NIAMS/National Institutes of Health Grant AR057404 (to J. Z.) and partially supported by NIAMS/National Institutes of Health Grants AR032808 and AR049184 (to E. R.) AG28614 (to J. M.), and AR054793 (to N. W.).

G93A indicates a SOD1 Gly to Ala mutation at position 93.

- SR

- sarcoplasmic reticulum

- ALS

- amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- BAPTA

- 1,2-bis(O-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- E-C

- excitation-contraction

- FDB

- flexor digitorum brevis

- SERCA

- sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase

- TMRE

- tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester

- NMJ

- neuromuscular junction

- cyto

- cytosolic

- mito

- mitochondrial.

REFERENCES

- 1. Eisenberg B. R. (1983) Quantitative Ultrastructure of Mammalian Skeletal Muscle, American Physiological Society, Bethesda, MD [Google Scholar]

- 2. Csordás G., Hajnóczky G. (2009) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 1352–1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bianchi K., Rimessi A., Prandini A., Szabadkai G., Rizzuto R. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1742, 119–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rizzuto R., Pozzan T. (2006) Physiol. Rev. 86, 369–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Santo-Domingo J., Demaurex N. (2010) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1797, 907–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kavanagh N. I., Ainscow E. K., Brand M. D. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1457, 57–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Szabadkai G., Duchen M. R. (2008) Physiology 23, 84–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dirksen R. T. (2009) Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 34, 389–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. O'Rourke B., Blatter L. A. (2009) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 46, 767–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhou J., Yi J., Fu R., Liu E., Siddique T., Ríos E., Deng H. X. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 705–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gurney M. E., Pu H., Chiu A. Y., Dal Canto M. C., Polchow C. Y., Alexander D. D., Caliendo J., Hentati A., Kwon Y. W., Deng H. X. (1994) Science 264, 1772–1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang X., Weisleder N., Collet C., Zhou J., Chu Y., Hirata Y., Zhao X., Pan Z., Brotto M., Cheng H., Ma J. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 525–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nagai T., Yamada S., Tominaga T., Ichikawa M., Miyawaki A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 10554–10559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang W., Fang H., Groom L., Cheng A., Zhang W., Liu J., Wang X., Li K., Han P., Zheng M., Yin J., Wang W., Mattson M. P., Kao J. P., Lakatta E. G., Sheu S. S., Ouyang K., Chen J., Dirksen R. T., Cheng H. (2008) Cell 134, 279–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. DiFranco M., Woods C. E., Capote J., Vergara J. L. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 14698–14703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pouvreau S., Royer L., Yi J., Brum G., Meissner G., Ríos E., Zhou J. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 5235–5240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kirichok Y., Krapivinsky G., Clapham D. E. (2004) Nature 427, 360–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matlib M. A., Zhou Z., Knight S., Ahmed S., Choi K. M., Krause-Bauer J., Phillips R., Altschuld R., Katsube Y., Sperelakis N., Bers D. M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 10223–10231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weisleder N., Brotto M., Komazaki S., Pan Z., Zhao X., Nosek T., Parness J., Takeshima H., Ma J. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 174, 639–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martins A. S., Shkryl V. M., Nowycky M. C., Shirokova N. (2008) J. Physiol. 586, 197–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Csernoch L., Zhou J., Stern M. D., Brum G., Ríos E. (2004) J. Physiol. 557, 43–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pacher P., Csordás P., Schneider T., Hajnóczky G. (2000) J. Physiol. 529, 553–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Andrienko T. N., Picht E., Bers D. M. (2009) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 46, 1027–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lännergren J., Westerblad H., Bruton J. D. (2001) J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 22, 265–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shkryl V. M., Shirokova N. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 1547–1554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boncompagni S., Rossi A. E., Micaroni M., Beznoussenko G. V., Polishchuk R. S., Dirksen R. T., Protasi F. (2009) Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1058–1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rudolf R., Magalhães P. J., Pozzan T. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 173, 187–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rudolf R., Mongillo M., Magalhães P. J., Pozzan T. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 166, 527–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Csordás G., Hajnóczky G. (2001) Cell Calcium 29, 249–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Royer L., Pouvreau S., Ríos E. (2008) J. Physiol. 586, 4609–4629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shirokova N., García J., Pizarro G., Ríos E. (1996) J. Gen. Physiol. 107, 1–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Melzer W., Rios E., Schneider M. F. (1984) Biophys. J. 45, 637–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. González A., Ríos E. (1993) J. Gen. Physiol. 102, 373–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schuhmeier R. P., Melzer W. (2004) J. Gen. Physiol. 123, 33–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R. Y. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260, 3440–3450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Palmer A. E., Tsien R. Y. (2006) Nat. Protoc. 1, 1057–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Isenberg G., Han S., Schiefer A., Wendt-Gallitelli M. F. (1993) Cardiovasc. Res. 27, 1800–1809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maack C., Cortassa S., Aon M. A., Ganesan A. N., Liu T., O'Rourke B. (2006) Circ. Res. 99, 172–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhou Z., Matlib M. A., Bers D. M. (1998) J. Physiol. 507, 379–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sedova M., Dedkova E. N., Blatter L. A. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 291, C840–C850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bruton J., Tavi P., Aydin J., Westerblad H., Lännergren J. (2003) J. Physiol. 551, 179–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zaidi N. F., Lagenaur C. F., Abramson J. J., Pessah I., Salama G. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 21725–21736 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brookes P. S., Yoon Y., Robotham J. L., Anders M. W., Sheu S. S. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 287, C817–C833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Durham W. J., Aracena-Parks P., Long C., Rossi A. E., Goonasekera S. A., Boncompagni S., Galvan D. L., Gilman C. P., Baker M. R., Shirokova N., Protasi F., Dirksen R., Hamilton S. L. (2008) Cell 133, 53–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bellinger A. M., Reiken S., Carlson C., Mongillo M., Liu X., Rothman L., Matecki S., Lacampagne A., Marks A. R. (2009) Nat. Med. 15, 325–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bers D. M. (2001) Excitation-Contraction Coupling and Cardiac Contractile Force, Kluwer, Dordrecht, Boston, MA [Google Scholar]