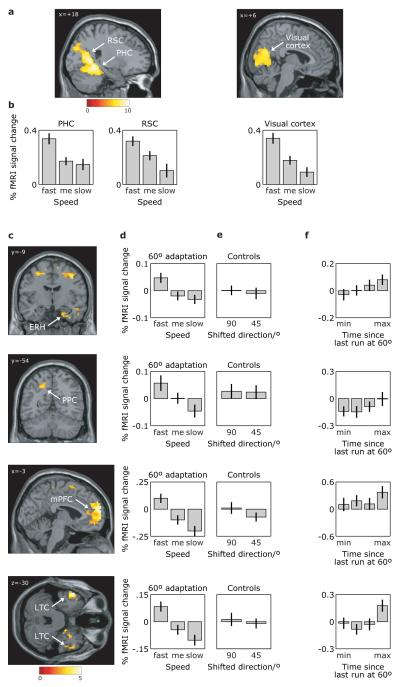

Figure 4. fMRI adaptation to running direction and to runs at 60° from it.

a, Activity in parahippocampal (PHC; 24/−48/−12; z=7.13), retrosplenial (RSC; 18/−57/18; z=7.16), and visual (peak at 18/−69/15; z=7.11) cortices shows adaptation to absolute running direction. Plot shows the t-statistic for the parameter estimate of the adaptation regressor (log(time since last run in current direction)). b, Adaptation is greater for faster runs, showing the adaptation effect for the peak voxels in the three regions for fast, medium, and slow runs. c, fMRI adaptation to runs at 60° from the current direction (regressor: log(time since last run at 60° from the current direction)) is seen in a network of regions, including: entorhinal cortex extending into subiculum (ERH; 21/−9/−30; z=3.28), anterior entorhinal/perirhinal (33/0/−27; z=3.69); posterior parietal (PPC; −18/−54/45; z=3.24); medial prefrontal (mPFC; −3/63/15; z=4.96), lateral temporal cortices (LTC; left: −54/9/−30; z=4.99; right: 42/15/−36; z=3.48) and precentral gyrus/superior frontal gyrus/motor cortex. These effects are independent of any basic (360°) directional adaptation (images are exclusively masked by the effects of basic directional adaptation at threshold P<0.05, uncorrected). d, The 60° adaptation effect is specific to fast runs. e, No significant adaptation is seen for fast running at 45° or 90° from the current direction. f, fMRI activity as a function of time since last fast run at 60° from the current direction (log(time) binned in quartiles), illustrating the adaptation effect. Signal in (d)-(f) shown for the peak voxel in (c). All effects significant at P<0.001, uncorrected; For display purposes, t-images are thresholded at P<0.000001 in (a) and P<0.01 in (c).