Abstract

Cell transplantation has been well explored for cartilage regeneration. We recently showed that the entire articular surface of a synovial joint can regenerate by endogenous cell homing and without cell transplantation. However, the sources of endogenous cells that regenerate articular cartilage remain elusive. Here, we studied whether cytokines not only chemotactically recruit adipose stem cells (ASCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and synovium stem cells (SSCs) but also induce chondrogenesis of the recruited cells. Recombinant human transforming growth factor-β3 (TGF-β3; 100 ng) and/or recombinant human stromal derived factor-1β (SDF-1β; 100 ng) was control released into an acellular collagen sponge cube with underlying ASCs, MSCs, or SSCs in monolayer culture. Although all cell types randomly migrated into the acellular collagen sponge cube, TGF-β3 and/or SDF-1β recruited significantly more cells than the cytokine-free control group. In 6 wk, TGF-β3 alone recruited substantial numbers of ASCs (558±65) and MSCs (302±52), whereas codelivery of TGF-β3 and SDF-1β was particularly chemotactic to SSCs (400±120). Proliferation of the recruited cells accounted for some, but far from all, of the observed cellularity. TGF-β3 and SDF-1β codelivery induced significantly higher aggrecan gene expression than the cytokine-free group for ASCs, MSCs, and SSCs. Type II collagen gene expression was also significantly higher for ASCs and SSCs by SDF-1 and TGF-β3 codelivery. Remarkably, the expression of aggrecan and type II collagen was detected among all cell types. Thus, homing of multiple stem/progenitor cell populations may potentially serve as an alternative or adjunctive approach to cell transplantation for cartilage regeneration.—Mendelson, A., Frank, E., Allred, C., Jones, E., Chen, M., Zhao, W., Mao, J. J. Chondrogenesis by chemotactic homing of synovium, bone marrow, and adipose stem cells in vitro.

Keywords: tissue engineering, TGF-β3, SDF-1, chondrocytes

Articular cartilage is recalcitrant to regeneration, owing largely to the scarcity of native stem and progenitor cells (1). Despite the presence of stem and progenitor cells in postnatal articular cartilage (2), it is difficult to conceive that they would serve as autologous cell sources for articular cartilage regeneration. Accordingly, chondrocytes or stem or progenitor cells from bone marrow, adipose tissue, synovium, and other sources have been investigated as cartilage-regenerating cells (3). The most prevalent model for articular cartilage regeneration has been focal defects that are filled with cartilage-forming cells with or without biomaterial scaffolds (4). Despite its scientific merit, cell transplantation for cartilage regeneration is associated with complicated, costly, and multistep procedures including donor site trauma, potential contamination, and possible immune rejection for allogeneic or xenogeneic cells (5). Long-term ex vivo manipulation of cells, including stem and progenitor cells, may lead to tumorigenesis (6–8). Culture and expansion of adult stem cells is not only time consuming but also limited to finite passages (9). Furthermore, culture of chondrocytes in a monolayer can lead to dedifferentiation and decreased proteoglycan and type II collagen production (10).

Tissue regeneration by cell homing is substantially underinvestigated in comparison to regeneration by cell transplantation. We recently showed that transforming growth factor β-3 (TGF-β3) acts as a cell homing cue that not only recruited endogenous cells but also prompted the regeneration of articular cartilage with structural and mechanical properties on par with native articular cartilage in a rabbit model (11). However, the sources of endogenous cells that regenerate articular cartilage remain elusive in cell homing models. Several stem or progenitor cell populations exist in tissues adjacent to articular cartilage defects, including bone marrow, adipose, synovium, periosteum, and skeletal muscle (12). Stem and progenitor cells have been isolated from these tissues, including mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), adipose stem cells (ASCs), and synovium stem cells (SSCs) (12). However, whether ASCs, MSCs, and SSCs serve as effective cell sources for in situ cell homing to regenerate articular cartilage has rarely been investigated.

In a cell homing approach for articular cartilage regeneration, one or more bioactive cues may be required for cell recruitment. Stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1) has gained significant interest as a cell homing factor in experimental studies. SDF-1 binds to the CXCR4 receptor present on membrane surfaces of multiple cell types, including embryonic stem cells, cord blood CD34+ cells, MSCs, ASCs, chondrocytes, osteoblasts, and SSCs (13–18). Notably, SDF-1 promotes cell migration within hours following receptor binding (19) and has been shown to improve the migration distance of MSCs in a biomaterial scaffold (20). For the present study, we speculated that the recruitment of cartilage-forming cells may need to be supplemented by factors to induce chondrogenesis. Accordingly, we incorporated TGF-β3, which has been shown to play a pivotal role in the chondrogenic differentiation of ASCs, MSCs, and SSCs (21). The objective of the present study was to devise a strategy for both the recruitment and chondrogenesis of ASCs, MSCs, and SSCs, all of which are adjacent to a full-size articular cartilage defect. A bioactive scaffold was devised with control-released TGF-β3 and/or SDF-1β from gelatin microspheres into an underlying porous collagen sponge cube for in situ cell recruitment and chondrogenesis. In this work, we show that the recruited cells expressed marked genes and proteins, including aggrecan and type II collagen, two primary macromolecules in articular cartilage. Thus these findings suggest that in situ cell homing for cartilage regeneration with bioactive scaffolds can be an alternative or adjunctive approach to the current approach of cartilage regeneration by cell transplantation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design and fabrication of the bioactive scaffold

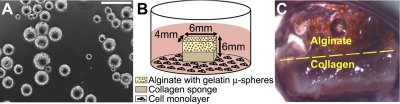

Gelatin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) microspheres were fabricated by water-in-oil emulsion and washed with acetone to remove residual oil (Fig. 1A), similar to previously published approaches (22, 23). Subsequently, microspheres were chemically cross-linked with 0.5% w/v glutaraldehyde and washed with 0.75% w/v glycine containing Tween to block residual aldehyde groups on unreacted glutaraldehyde. Microspheres were visualized by light microscopy to ensure shape uniformity. Following lyophilization, gelatin microspheres were sterilized using ethylene oxide. Microsphere aliquots (30 mg) were rehydrated in 30 μl PBS containing 100 ng recombinant human TGF-β3 (Cell BioSciences, Santa Clara, CA, USA), 100 ng recombinant human SDF-1β (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), or PBS. At pH 7.4, the positively charged TGF-β3 and SDF-1β were electrostatically bound to the negatively charged gelatin microspheres. Growth factor concentrations were based on their efficacy in previous work (20, 24, 25). Calcium alginate (2% w/v; FMC BioPolymer, Philadelphia, PA, USA) was mixed with 30 mg (dry wt) of microspheres, deposited over a type I and III collagen sponge (Helistat; Integra LifeSciences, Plainsboro, NJ, USA; ref. 26), and cross-linked with calcium chloride. The total dimensions of the bilayered bioscaffold were 6 × 6 × 4 mm (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Experimental schematics and tissue morphology. A) Light microscopy of microspheres with an average diameter of 70.8 ± 21.5 μm. Scale bar = 200 μm. B) Bilayered scaffold with an alginate layer containing gelatin microspheres overlaying a collagen sponge cube. Overall scaffold dimensions were 6 × 6 × 4 mm. Scaffolds were placed in the culture of ASCs, MSCs, and SSCs. C) Gross scaffold morphology following 3 wk culture. Glistening white tissue can be seen in the scaffold's collagen region.

Isolation of primary human ASCs, MSCs, and SSCs

Human bone marrow MSCs (AllCells, Emeryville, CA, USA), human ASCs, and human SSCs were isolated from fresh adult donor samples using previously established methods (27–31). MSCs were purified from bone marrow using the RosetteSep Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Enrichment Cocktail (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, the bone marrow sample was mixed with the RosetteSep Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Enrichment Cocktail containing antibodies directed against cell surface antigens on hematopoietic cells and glycophorin A on red blood cells. Following 20 min of incubation, the bone marrow mixture was diluted with PBS containing 2% FBS and 1 mM EDTA. The diluted sample was subsequently placed on top of Ficoll-Paque and centrifuged to form a density gradient. The enriched MSCs were collected from the Ficoll-Paque interface, washed with PBS containing 2% FBS and 1 mM EDTA, and plated. To ensure multilineage potential, MSCs were differentiated into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes for quality control (data not shown). Ethical approval for isolating SSCs was obtained from the Leeds Teaching Hospitals National Health Service Trust Ethics Committee. Synovial membranes were isolated aseptically, finely minced, washed in PBS, and digested in 0.25% collagenase (Stem Cell Technologies). After incubation in a rotator at 37°C for 5 h, the collagenase solution was filtered through a 70-μm filter (BD, Oxford, UK). The liquid fraction containing the cells was centrifuged and plated (28, 31). Synovium cells were subjected to extended phenotyping (12, 32) and were shown to differentiate into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes (33). ASCs were isolated from subcutaneous liposuction aspirates and digested with 0.25 mg collagenase (200 U/mg)/ml of Krebs-Ringer-bicarbonate solution (Sigma) at 37°C for 40 min. Following centrifugation, the stromal-vascular fraction was isolated and plated, per our prior methods (34).

In vitro chondrogenesis by cell homing

ASCs and MSCs were cultured with DMEM (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 10% FBS (Life Technologies), and 5% antibiotics/antimicrotics. SSCs were cultured using Mesencult (Stem Cell Technologies). ASCs, MSCs, and SSCs were expanded to passage 3 and seeded in 6-well plates with 105 cells/well. Four conditions were tested: cytokine free, TGF-β3 alone, SDF-1β alone, and combined TGF-β3 and SDF-1β. SDF-1β was selected because it promotes the migration of multiple cell types (20). TGF-β3 was investigated for its ability to induce chondrogenesis (35–38). The combined SDF-1β and TGF-β3 condition consisted of 15 mg SDF-1β microspheres and 15 mg TGF-β3 microspheres (100 ng TGF-β3 or SDF-1β 1/15 mg microspheres). All scaffolds were placed in culture wells and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 with medium changed every 3 d. Scaffolds were harvested after 3 h (n=6), 1 wk (n=6), 3 wk (n=6), and 6 wk (n=6) and cut vertically, with one part used for real-time PCR and the other for histology and immunohistochemistry.

TGF-β3 and SDF-1β release kinetics

In a separate experiment, 30 mg of microspheres (dry wt%) containing either 100 ng SDF-1β or 100 ng TGF-β3 was placed in separate wells containing PBS and 1% BSA (n=3). As the gelatin microsphere matrix degraded, the encapsulated growth factor was speculated to be released. To ascertain this, samples of PBS were collected after 0, 1, 2, 4, 9, 12, 18, 24, 29, 34, 38, and 42 d and replaced with fresh PBS containing 1% BSA. Total released SDF-1β or TGF-β3 from microspheres per time point was determined by ELISA.

Cytokine effects on cell proliferation

Cell metabolic activity was measured to appreciate the potential contribution of cell proliferation on SDF-1β and/or TGF-β3 delivery to the overall cellularity in the collagen sponge. A 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) assay was conducted with the CellTiter 96 Aqueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Multiple plates were seeded with 4000 cells each and treated with basal medium supplemented with SDF-1β or TGF-β3 (concentrations: 1, 10, or 100 ng), with cytokine-free basal medium as a control. The absorbance was assessed at 490 nm after 0, 24, 48, and 96 h using a standard curve.

Histology and quantification of cell migration

Scaffolds were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 μm thickness. Sections from the top, middle, and bottom of each scaffold were stained with DAPI (Vectorshield, Burlingame, CA, USA) to visualize cell nuclei and subsequently quantified to derive the numbers of cells that were recruited into the collagen sponges. Additional sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and 0.1% toluidine blue (Sigma) to assess cartilage matrix formation and sulfated polysaccharides. For aggrecan immunohistochemistry, sections were digested with pepsin (0.6% w/v) and 3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS, blocked with 3% normal horse serum (v/v), and then incubated with primary antibody (1:300) for 90 min at room temperature. A biotinylated secondary anti-mouse antibody (1:200) was used to detect immunoreactivity. For collagen type II immunohistochemistry, sections were digested with pepsin (0.6% w/v) and 3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS, blocked with 10% normal goat serum (v/v), and then incubated with primary antibody (1:80) for 90 min at room temperature. Envision system labeled polymer-horseradish-peroxidase (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) was used to detect immunoreactivity. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. Normal healthy human articular cartilage served as a positive control.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Scaffolds were homogenized using a Powergen 125 (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), and total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 0.2 ml chloroform was added to the homogenized scaffold and centrifuged. The aqueous, RNA-containing phase was separated and mixed with 0.5 ml isopropyl alcohol and 20 μg glycogen. Following 10 min incubation, samples were centrifuged to form a pellet, washed with 75% ethanol, and resuspended in dH20. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). RT-PCR was performed using the TaqMan Assay Protocol (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA): hold for 2 min at 50°C, hold for 10 min at 95°C, and 50 cycles of melt for 15 s at 95°C and anneal/extend for 1 min at 60°C. All reactions were run in triplicate. Primers from Applied Biosystems were Hs00202971_m1 for aggrecan, Hs01060344_g1 for type II collagen, and Hs99999901_s1 for 18S. Aggrecan and collagen type II expression was normalized to 18S and subsequently normalized to the negative control.

Statistical analysis

For each condition, the results were pooled from 2 independent sets of experiments, with each experiment performed in at least triplicate. On confirmation of a normal data distribution, a 1-way ANOVA with post hoc least significant difference test was used to detect significant differences using a value of P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Cytokine release kinetics from gelatin microspheres

The average diameter of the gelatin microspheres was 70.8 ± 21.5 μm (Fig. 1A). Microencapsulated SDF-1β and TGF-β3 were control released over the tested 42 d and displayed similar release patterns but at different amplitudes (Supplemental Fig. S1). By 42 d, 42.3% SDF-1β and 60.8% TGF-β3 were released, primarily as a function of their different molecular weights.

Chemotaxis of stem and progenitor cells by control-released TGF-β3 and/or SDF-1β

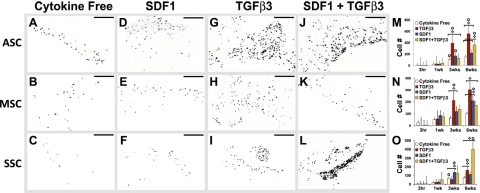

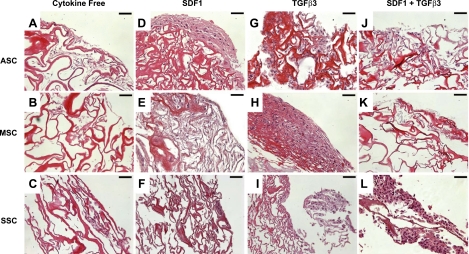

Scaffolds with control-released TGF-β3 and/or SDF-1β were cultured over primary human ASCs, MSCs, or SSCs (Fig. 1B). A uniform layer of glistening white tissue was formed by the recruited cells in the collagen sponge cube as early as 3 wk (Fig. 1C). DAPI staining (inverted for demonstration) revealed the nuclei of the cells that had migrated into the collagen sponge cubes from the underlying and adjacent ASCs, MSCs, or SSCs (Fig. 2A–L). Sections from the top, middle, and bottom of the scaffolds were DAPI stained and pooled to calculate quantitative data (Fig. 2M–O). A general increase in cellularity was observed in the tested scaffolds at 6 wk regardless of cell type or cytokines (Fig. 2M–O). TGF-β3 recruited significantly more ASCs (558±65) than all other conditions, followed by SDF-1β and TGF-β3 codelivery (363±46.2; Fig. 2M). TGF-β3 recruited significantly more MSCs (302±52) than SDF-1β (208±37; Fig. 2N). SDF-1β and TGF-β3 codelivery recruited significantly more SSCs (400±120) than all other conditions, followed by TGF-β3 alone (157±18; Fig. 2O). For all 3 cell types, significantly fewer cells were present in the cytokine-free group than all other groups (Fig. 2M–O). Matrix synthesis was evident in some, but not all, groups (Fig. 3). In contrast to little matrix synthesis in cytokine-free samples (Fig. 3A–C), tissue was formed in vitro by the recruited ASCs, MSCs, or SSCs in SDF-1β delivery, TGF-β3 delivery, or SDF-1β and TGF-β3 codelivery samples (Fig. 3D–F, G–I, J–L, respectively).

Figure 2.

Chemokine-mediated recruitment of ASCs, MSCs, and SSCs. After 6 wk in the culture of ASCs, MSCs, and SSCs, scaffolds were sectioned and stained with DAPI to visualize the cell nuclei. Sections from the top, middle, and bottom of the scaffold were stained (n=8–12). Four conditions were tested: cytokine free (A–C), SDF-1β (D–F), TGF-β3 (G–I), and TGF-β3 + SDF-1β (J–L) for ASCs (A, D, G, J), MSCs (B, E, H, K), and SSCs (C, F, I, L). All sections were quantified to determine the chemotactic effects of SDF-1β and/or TGF-β3 on ASCs (M), MSCs (N), and SSCs (O). Scale bars = 200 μm. Values shown are means ± se. Diamonds indicate significant difference over other conditions at same time point (P<0.05); circles indicate significant difference over previous time point (P<0.05).

Figure 3.

Tissue formation on cytokine-induced cell recruitment. After 6 wk, scaffolds were stained with H&E for each of the 4 conditions tested: cytokine free (A–C), SDF-1β (D–F), TGF-β3 (G–I), and TGF-β3+SDF-1 (J–L) for ASCs (A, D, G, J), MSCs (B, E, H, K), and SSCs (C, F, I, L). Significant matrix deposition can be seen in ASCs due to SDF-1β (D), MSCs due to TGF-β3 (H), and SSCs due to SDF-1 + TGF-β3 (L), indicating that the scaffold substrate is conducive to cell attachment. Scale bars 50 μm.

Chondrogenesis of recruited stem and progenitor cells

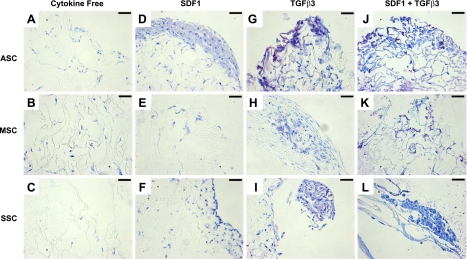

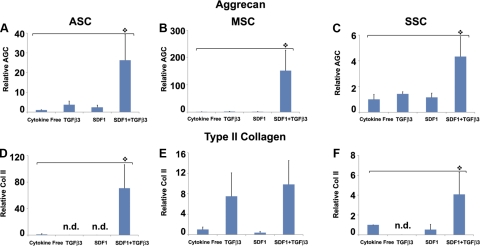

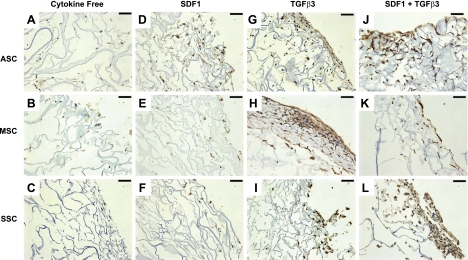

Cartilage regeneration by cell homing not only requires cell recruitment into an anatomic compartment but also chondrogenesis of the recruited cells. After 6 wk, toluidine blue staining was most notable in the TGF-β3 group (Fig. 4G–I) and the TGF-β3 and SDF-1β codelivery group (Fig. 4J–L) for all 3 cell types. In contrast, there was little positive toluidine blue staining in the cytokine-free groups for all 3 cell types (Fig. 4A–C). Aggrecan and type II collagen are two predominant macromolecules in articular cartilage (39). Quantitative real-time PCR showed significantly higher aggrecan expression on TGF-β3 and SDF-1β codelivery than the cytokine-free group for ASCs, MSCs, and SSCs (Fig. 5A–C). Type II collagen mRNA was significantly higher for ASCs and SSCs on TGF-β3 and SDF-1β codelivery than other groups (Fig. 5D, F).

Figure 4.

Chondrogenic differentiation of chemokine-recruited cells. After 6 wk, sections were stained with toluidine blue for each of the 4 conditions tested: cytokine free (A–C), SDF-1β (D–F), TGF-β3 (G–I), and TGF-β3 + SDF-1β (J–L) for ASCs (A, D, G, J), MSCs (B, E, H, K), and SSCs (C, F, I, L). Scale bars = 50 μm. Positive staining reveals chondrogenesis among the TGF-β3-only group (G–I) and the SDF-1β + TGF-β3 (J–L) group for all 3 cell types.

Figure 5.

Gene expression of aggrecan and type II collagen. After 6 wk, scaffolds were digested, and encapsulated cells were tested for aggrecan expression (A–C) and type II collagen (Col II; D–F) using RT-PCR (n=3). Relative aggrecan expression was significantly higher on TGF-β3 + SDF-1β codelivery for ASCs (A), MSCs (B), and SSCs (C) than the cytokine-free groups. TGF-β3 + SDF-1β codelivery also induced significantly higher Col II expression for ASCs (D) and SSCs (F) than the cytokine-free group. n.d., not detected (expression below detection limit).

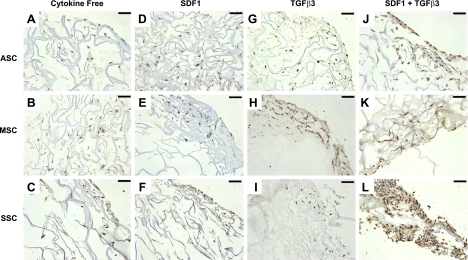

Immunohistochemistry staining revealed aggrecan (Fig. 6) and type II collagen (Fig. 7) expression for ASCs, MSCs, and SSCs, confirming protein synthesis in addition to mRNA expression. Aggrecan antibody staining was present in the extracellular matrix for all 3 cell types in the TGF-β3 and SDF-1β codelivery group for ASCs, MSCs, and SSCs (Fig. 6J–L) and the TGF-β3 alone group for ASCs and MSCs (Fig. 6G, H). However, aggrecan antibody staining was minimal among the cytokine-free and SDF-1β-only samples for all 3 cell types (Fig. 6A–F). There was marked collagen type II antibody staining for the TGF-β3 and SDF-1β codelivery samples (Fig. 7J–L), as well as the TGF-β3 group for MSCs (Fig. 7H). Positive immunohistochemical staining of aggrecan and collagen type II on TGF-β3 delivery or combined TGF-β3 and SDF-1β codelivery suggests that TGF-β3 was essential for chondrogenic differentiation of recruited ASCs, MSCs and SSCs.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry staining of aggrecan expression. After 6 wk, scaffold samples were immunostained with aggrecan antibody for each of the 4 conditions tested: cytokine free (A–C), SDF-1β (D–F), TGF-β3 (G–I), and TGF-β3 + SDF-1β (J–L) for ASCs (A, D, G, J), MSCs (B, E, H, K), and SSCs (C, F, I, L). Positive aggrecan staining revealed chondrogenesis among the TGF-β3-only group (G–I) and the SDF-1β + TGF-β3 group (J–L) for all 3 cell types. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Figure 7.

Immunohistochemistry staining of type II collagen. After 6 wk, scaffold samples were immunostained with Col II for each of the 4 conditions: cytokine free (A–C), SDF-1β (D–F), TGF-β3 (G–I), and TGF-β3 + SDF-1β (J–L) for ASCs (A, D, G, J), MSCs (B, E, H, K), and SSCs (C, F, I, L). Positive Col II staining revealed chondrogenesis among the TGF-β3-only group for MSCs (H) and the SDF-1β + TGF-β3 group (J–L) for all 3 cell types. Scale bars = 50 μm.

TGF-β3 and SDF-1β have a modest effect on cell proliferation

MTS assay revealed that TGF-β3 and/or SDF-1β delivery had modest effects on cell proliferation (Supplemental Fig. S2). Three doses of TGF-β3 or SDF-1β were separately supplemented in ASC, MSC, and SSC cultures for up to 96 h. Cell proliferation was significantly higher for 1 ng TGF-β3-treated MSCs than the control (n=3; P<0.05). There was also a significant increase in ASC proliferation when treated with 100 ng TGF-β3 (n=3; P<0.05) over the control. Cell proliferation rates of SSCs increased significantly (n=3; P<0.05) over the control in response to 10 ng SDF-1β, 100 ng SDF-1β, and all 3 doses of TGF-β3.

DISCUSSION

One of the key findings of the present work is that TGF-β3 not only effectively recruited both ASCs and MSCs into the scaffold but also induced the recruited cells to undergo chondrogenesis. Interestingly, TGF-β3 had somewhat modest effects on the recruitment of SSCs in this in vitro system, with the exception of the later time course. The robustness of TGF-β3 in cell recruitment confirms its efficacy in the regeneration of an entire articular surface in vivo by cell homing in our recent work (11). Thus, TGF-β3 appears to act as a potent chemotactic molecule and is capable of recruiting at least mesenchymal cells of bone marrow, adipose tissue, and perhaps synovium. Given the presently designed slow release rate of TGF-β3, it is conceivable that the initially released TGF-β3 was responsible for cell recruitment, whereas later released TGF-β3 induced chondrogenesis. In contrast, the capacity of SDF-1β in the recruitment of ASCs and MSCs is below its expected potency as a highly potent chemotactic cytokine for other cell types, such as lymphocytes and macrophages (13). The significant effects of SDF-1β in the recruitment of MSCs by 6 wk in our current in vitro model are consistent with previous reports of MSC migration by SDF-1β (40, 41). Remarkably, the combined effects of TGF-β3 and SDF-1β in the recruitment of ASCs, MSCs, and SSCs suggest their potential synergistic actions. In particular, codelivery of TGF-β3 and SDF-1β seems quite chemotactic for SSCs.

Most cell migration assays are performed in monolayer cell cultures, transwells, or Boyden chambers. The present 3-D cell migration system is designed to create an acellular bioscaffold to be populated by cells, including stem and progenitor cells that are purposefully recruited by specific bioactive cues. The motivation for the design of such a system is as follows. First, specific cells that are recruited into an acellular bioscaffold may generate tissues in a cell-homing approach for tissue regeneration. It is conceivable that different cell types may be recruited by specific bioactive cues, including peptides, proteins, or chemical compounds. This approach may have applications in both tissue regeneration and drug development. Second, identification of bioactive cues in the recruitment of specific cell types may constitute a novel approach for tissue regeneration by cell homing. Cell recruitment into a predesigned bioscaffold in vivo may serve as an alternative or adjunctive approach to tissue regeneration by cell transplantation. If certain tissues can be regenerated by chemotaxis of endogenous cells without cell transplantation, development of regenerative therapies may be simplified by circumventing cell isolation, ex vivo manipulation, packing, shipping, and sterilization. It is known that most of the tissues and organs thus studied in the body harbor stem/progenitor cells. Targeted chemotaxis of endogenous tissue-forming cells, including stem/progenitor cells, may be capable of regenerating tissues, perhaps without cell transplantation. Initial examples of tissue regeneration by endogenous stem cell homing include regeneration of cartilage, bone, dermal, and neuromuscular tissues in severed digits, dental pulp, and periodontium (11, 42, 43). Amphibians, such as salamanders, are well recognized for their ability to spontaneously regenerate severed limbs, whereas this ability may have been deprived in evolutionally advanced species (44). However, it remains to be studied whether endogenous regenerative capacity can be reinvigorated by specific, interventional bioactive cues that are delivered at critical times in wound healing. On the other hand, reservations about tissue regeneration by endogenous cell homing, without cell transplantation, include skepticism of the complexity of tissues regenerated, potential toxicity of concentrated bioactive cues, and specificity of a hypothetical match between a given cell type and a bioactive cue. Nevertheless, the presently adopted control-release system, similar to previous work in this area by us and others (45, 46), addresses several potential pitfalls of bioactive cue delivery, such as premature cytokine denature and diffusion. Furthermore, the amount of cross-linking of gelatin, which serves as the shell of encapsulated growth factors in the present study, can be adjusted to modulate release kinetics as a function of biological needs.

A number of cytokines are known to induce cell migration, including SDF-1β, stem cell factor, insulin-like growth factor-1, and granulocyte colony stimulating factor (24, 47, 48). The data described here substantiate our recent study (11) reporting that TGF-β3 has potent cell homing capacity, in addition to its reported roles in chondrogenesis and fetal wound healing (49). Strikingly, we discovered that TGF-β3 is able to recruit both ASCs and MSCs, which natively occupy different anatomic compartments. Remarkably, the TGF-β3 and SDF-1β axis appears particularly potent in the recruitment of SSCs. Positive toluidine blue staining in combination with positive gene expression and protein synthesis of aggrecan and type II collagen suggests in vitro chondrogenesis in 3-D scaffolds by ASCs, MSCs, and SSCs, none of which are known to spontaneously differentiate into chondrocytes in monolayer culture. Notably, the present findings indicate that SDF-1β has little chondrogenic potential. TGF-β3, in addition to its broad effect on cell recruitment, induces chondrogenesis of recruited stem and progenitor cells. Mitogenic effects of SDF-1β and/or TGF-β3 in the present work, most notably for SSCs, are superimposed with cell recruitment and can be further distinguished from cell migration in future studies. However, the net effects of cell proliferation and cell recruitment may be facilitative for tissue regeneration given the frequent shortage of tissue-forming cells in wound healing environments, including cartilage and/or osteochondral defects. Although ASCs, MSCs, and SSCs have been investigated as candidate cells for transplantation in the healing of cartilage and osteochondral defects, our present findings provide a strong rationale for additional in vivo studies to test the efficacy of homing ASCs, MSCs, and SSCs, all of which are natively found near a synovial joint, for cartilage regeneration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ryan V. Maneevese, Brian H. Sybo, Brandon R. Knapp, Stephanie Bohaczuk, and Andrew Chang for technical assistance. Adipose stem cells were a generous gift from Dr. Jeffrey M. Gimble (Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University, Baton Rogue, LA, USA).

The present study is funded in part by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants RC2-D-E020767 and R01-EB-0062621.

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mao J. J. (2005) Stem-cell-driven regeneration of synovial joints. Biol. Cell 97, 289–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dowthwaite G. P., Bishop J. C., Redman S. N., Khan I. M., Rooney P., Evans D. J., Haughton L., Bayram Z., Boyer S., Thomson B., Wolfe M. S., Archer C. W. (2004) The surface of articular cartilage contains a progenitor cell population. J. Cell Sci. 117, 889–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Raghunath J., Salacinski H. J., Sales K. M., Butler P. E., Seifalian A. M. (2005) Advancing cartilage tissue engineering: the application of stem cell technology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 16, 503–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chung C., Burdick J. A. (2008) Engineering cartilage tissue. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 60, 243–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fodor W. L. (2003) Tissue engineering and cell based therapies, from the bench to the clinic: the potential to replace, repair and regenerate. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 1, 102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim J., Kang J. W., Park J. H., Choi Y., Choi K. S., Park K. D., Baek D. H., Seong S. K., Min H. K., Kim H. S. (2009) Biological characterization of long-term cultured human mesenchymal stem cells. Arch. Pharm. Res. 32, 117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lepperdinger G., Brunauer R., Jamnig A., Laschober G., Kassem M. (2008) Controversial issue: is it safe to employ mesenchymal stem cells in cell-based therapies? Exp. Gerontol. 43, 1018–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rubio D., Garcia-Castro J., Martín M. C., de la Fuente R., Cigudosa J. C., Lloyd A. C., Bernad A. (2005) Spontaneous human adult stem cell transformation. Cancer Res. 65, 3035–3039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bladergroen B. A., Siebum B., Siebers-Vermeulen K. G., Van Kuppevelt T. H., Poot A. A., Feijen J., Figdor C. G., Torensma R. (2009) In vivo recruitment of hematopoietic cells using stromal cell-derived factor 1 alpha-loaded heparinized three-dimensional collagen scaffolds. Tissue Eng. A 15, 1591–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Benya P. D., Shaffer J. D. (1982) Dedifferentiated chondrocytes reexpress the differentiated collagen phenotype when cultured in agarose gels. Cell 30, 215–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee C. H., Cook J. L., Mendelson A., Moioli E. K., Yao H., Mao J. J. (2010) Regeneration of the articular surface of the rabbit synovial joint by cell homing: a proof of concept study. Lancet 376, 440–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jones E. A., English A., Henshaw K., Kinsey S. E., Markham A. F., Emery P., McGonagle D. (2004) Enumeration and phenotypic characterization of synovial fluid multipotential mesenchymal progenitor cells in inflammatory and degenerative arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 50, 817–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Son B. R., Marquez-Curtis L. A., Kucia M., Wysoczynski M., Turner A. R., Ratajczak J., Ratajczak M. Z., Janowska-Wieczorek A. (2006) Migration of bone marrow and cord blood mesenchymal stem cells in vitro is regulated by stromal-derived factor-1-CXCR4 and hepatocyte growth factor-c-met axes and involves matrix metalloproteinases. Stem Cells 24, 1254–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mazzetti I., Magagnoli G., Paoletti S., Uguccioni M., Olivotto E., Vitellozzi R., Cattini L., Facchini A., Borzì R. M. (2004) A role for chemokines in the induction of chondrocyte phenotype modulation. Arthritis Rheum. 50, 112–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thangarajah H., Vial I. N., Chang E., El-Ftesi S., Januszyk M., Chang E. I., Paterno J., Neofytou E., Longaker M. T., Gurtner G. C. (2009) IFATS collection: adipose stromal cells adopt a proangiogenic phenotype under the influence of hypoxia. Stem Cells 27, 266–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen T., Bai H., Shao Y., Arzigian M., Janzen V., Attar E., Xie Y., Scadden D. T., Wang Z. Z. (2007) Stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4 signaling modifies the capillary-like organization of human embryonic stem cell-derived endothelium in vitro. Stem Cells 25, 392–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Burger J. A., Zvaifler N. J., Tsukada N., Firestein G. S., Kipps T. J. (2001) Fibroblast-like synoviocytes support B-cell pseudoemperipolesis via a stromal cell-derived factor-1- and CD106 (VCAM-1)-dependent mechanism. J. Clin. Invest. 107, 305–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Christopher M. J., Liu F., Hilton M. J., Long F., Link D. C. (2009) Suppression of CXCL12 production by bone marrow osteoblasts is a common and critical pathway for cytokine-induced mobilization. Blood 114, 1331–1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schaefer D., Martin I., Jundt G., Seidel J., Heberer M., Grodzinsky A., Bergin I., Vunjak-Novakovic G., Freed L. E. (2002) Tissue-engineered composites for the repair of large osteochondral defects. Arthritis Rheum. 46, 2524–2534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schantz J. T., Chim H., Whiteman M. (2007) Cell guidance in tissue engineering: SDF-1 mediates site-directed homing of mesenchymal stem cells within three-dimensional polycaprolactone scaffolds. Tissue Eng. 13, p. 2615–2624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gao J., Yao J. Q., Caplan A. I. (2007) Stem cells for tissue engineering of articular cartilage. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H 221, 441–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fan H., Hu Y., Qin L., Li X., Wu H., Lv R. (2006) Porous gelatin-chondroitin-hyaluronate tri-copolymer scaffold containing microspheres loaded with TGF-beta1 induces differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in vivo for enhancing cartilage repair. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 77, 785–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kimura Y., Ozeki M., Inamoto T., Tabata Y. (2003) Adipose tissue engineering based on human preadipocytes combined with gelatin microspheres containing basic fibroblast growth factor. Biomaterials 24, 2513–2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li Y., Yu X., Lin S., Li X., Zhang S., Song Y. H. (2007) Insulin-like growth factor 1 enhances the migratory capacity of mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 356, 780–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yun K., Moon H. T. (2008) Inducing chondrogenic differentiation in injectable hydrogels embedded with rabbit chondrocytes and growth factor for neocartilage formation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 105, 122–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lutolf M. P., Weber F. E., Schmoekel H. G., Schense J. C., Kohler T., Müller R., Hubbell J. A. (2003) Repair of bone defects using synthetic mimetics of collagenous extracellular matrices. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 513–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marion N. W., Mao J. J. (2006) Mesenchymal stem cells and tissue engineering. Meth. Enzymol. 420, 339–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Karystinou A., Dell'Accio F., Kurth T. B., Wackerhage H., Khan I. M., Archer C. W., Jones E. A., Mitsiadis T. A., De Bari C. (2009) Distinct mesenchymal progenitor cell subsets in the adult human synovium. Rheumatology 48, 1057–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alhadlaq A., Elisseeff J. H., Hong L., Williams C. G., Caplan A. I., Sharma B., Kopher R. A., Tomkoria S., Lennon D. P., Lopez A., Mao J. J. (2004) Adult stem cell driven genesis of human-shaped articular condyle. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 32, 911–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Awad H. A., Halvorsen Y. D., Gimble J. M., Guilak F. (2004) Chondrogenic differentiation of adipose-derived adult stem cells in agarose, alginate, and gelatin scaffolds. Biomaterials 25, 3211–3222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. De Bari C., Dell'Accio F., Tylzanowski P., Luyten F. P. (2001) Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells from adult human synovial membrane. Arthritis Rheum. 44, 1928–1942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. De Bari C., Dell'Accio F., Karystinou A., Guillot P. V., Fisk N. M., Jones E. A., McGonagle D., Khan I. M., Archer C. W., Mitsiadis T. A., Donaldson A. N., Luyten F. P., Pitzalis C. (2008) A biomarker-based mathematical model to predict bone-forming potency of human synovial and periosteal mesenchymal stem cells. Arthritis Rheum. 58, 240–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jones E., Churchman S. M., English A., Buch M. H., Horner E. A., Burgoyne C. H., Reece R., Kinsey S., Emery P., McGonagle D., Ponchel F. (2009) Mesenchymal stem cells in rheumatoid synovium: enumeration and functional assessment in relation to synovial inflammation level. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 450–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moioli E. K., Chen M., Yang R., Shah B., Wu J., Mao J. J. Hybrid adipogenic implants from adipose stem cells for soft tissue reconstruction in vivo. Tissue Eng. A 16, 3299–3307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee C. H., Marion N. W, Hollister S., Mao J. J. (2009) Tissue formation and vascularization in anatomically shaped human joint condyle ectopically in vivo. Tissue Eng. A 15, 3923–3930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thorpe S. D., Buckley C. T., Vinardell T., O'Brien F. J., Campbell V. A., Kelly D. J. (2010) The response of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells to dynamic compression following TGF-beta3 induced chondrogenic differentiation. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 38, 2896–2909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hildner F., Peterbauer A., Wolbank S., Nürnberger S., Marlovits S., Redl H., van Griensven M., Gabriel C. (2010) FGF-2 abolishes the chondrogenic effect of combined BMP-6 and TGF-beta in human adipose derived stem cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 94, 978–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Varshney R. R., Zhou R., Hao J., Yeo S. S., Chooi W. H., Fan J., Wang D. A. (2010) Chondrogenesis of synovium-derived mesenchymal stem cells in gene-transferred co-culture system. Biomaterials 31, 6876–6891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Knudson C. B., Knudson W. (2001) Cartilage proteoglycans. Semin. Cell. Dev. Biol. 12, 69–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shen W., Chen X., Chen J., Yin Z., Heng B. C., Chen W., Ouyang H. W. (2010) The effect of incorporation of exogenous stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha within a knitted silk-collagen sponge scaffold on tendon regeneration. Biomaterials 31, 7239–7249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. He X., Ma J., Jabbari E. (2010) Migration of marrow stromal cells in response to sustained release of stromal-derived factor-1alpha from poly(lactide ethylene oxide fumarate) hydrogels. Int. J. Pharm. 390, 107–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kim J. Y., Xin X., Moioli E. K., Chung J., Lee C. H., Chen M., Fu S. Y., Koch P. D., Mao J. J. (2010) Regeneration of dental-pulp-like tissue by chemotaxis-induced cell homing. Tissue Eng. A 16, 3023–3031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Agrawal V., Johnson S. A., Reing J., Zhang L., Tottey S., Wang G., Hirschi K. K., Braunhut S., Gudas L. J., Badylak S. F. Epimorphic regeneration approach to tissue replacement in adult mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 3351–3355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kumar A., Gates P. B., Brockes J. P. (2007) Positional identity of adult stem cells in salamander limb regeneration. C. R. Biol. 330, 485–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee C. H., Shah B., Moioli E. K., Mao J. J. CTGF directs fibroblast differentiation from human mesenchymal stem/stromal cells and defines connective tissue healing in a rodent injury model. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 3340–3349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mao J. J., Stosich M. S., Moioli E., Lee C. H., Fu S. Y., Bastian B., Eisig S. B., Zemnick C., Ascherman J., Wu J., Rohde C., Ascherman J. (2010) Facial reconstruction by biosurgery: cell transplantation vs. cell homing. Tiss. Eng. B 16, 257–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pelus L. M., Fukuda S. (2008) Chemokine-mobilized adult stem cells; defining a better hematopoietic graft. Leukemia 22, 466–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aiuti A., Webb I. J., Bleul C., Springer T., Gutierrez-Ramos J. C. (1997) The chemokine SDF-1 is a chemoattractant for human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells and provides a new mechanism to explain the mobilization of CD34+ progenitors to peripheral blood. J. Exp. Med. 185, 111–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zheng Z., Nguyen C., Zhang X., Khorasani H., Wang J. Z., Zara J. N., Chu F., Yin W., Pang S., Le A., Ting K., Soo C. (2011) Delayed wound closure in fibromodulin-deficient mice is associated with increased TGF-beta3 signaling. J. Invest. Dermatol. 131, 769–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.