Abstract

Background:

Melasma is an acquired increased pigmentation of the skin, characterized by gray-brown symmetrical patches, mostly in the sun-exposed areas of the skin. The pathogenesis is unknown, but genetic or hormonal influences with UV radiation are important.

Aims:

Our present research aims to study the clinico-epidemiological pattern and the precipitating or provocation factors in melasma.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 312 patients were enrolled for the study over a period of one year.

Results:

The mean age of patients with melasma was 33.45 years, ranging from 14 to 54 years. There was female preponderance with a female to male ratio of approximately 4 : 1. The mean age of onset was 29.99 years, with the youngest and oldest being 11 and 49 years, respectively. The patients sought medical treatment on an average of 3.59 years after appearance of melasma. About 55.12% of our patients reported that their disease exacerbated during sun exposure. Among 250 female patients, 56 reported pregnancy and 46 reported oral contraceptive as the precipitating factors. Only 34 patients had given history of exacerbation of melasma during pregnancy. A positive family history of melasma was observed in 104 (33.33%) patients. Centrofacial was the most common pattern (55.44%) observed in the present study. Wood light examination showed the dermal type being the most common in 54.48% and epidermal and mixed were seen in 21.47% and 24.03% of the cases, respectively. We tried to find an association with endocrinal diseases and observed that 20 of them had hypothyroidism.

Conclusion:

The exact cause of melasma is unknown. However, many factors have been implicated in the etiopathogenesis of this disorder. Here we try to identify the causative factors and provocation to develop melasma.

Keywords: Clinical, epidemiological, melasma

Introduction

Melasma (a term derived from the Greek word ‘melas’ meaning black) is a common, acquired hypermelanosis that occurs in sun-exposed areas, mostly on the face, occasionally on the neck, and rarely on the forearms. The term, ‘chloasma’ (from the Greek word, ‘chloazein’ meaning ‘to be green’) is often used to describe melasma developing during pregnancy; but the pigmentation never appears to be green, therefore the term, ‘melasma’ is preferred.[1]

The exact prevalence of melasma is unknown in most of the countries. Melasma is a very common cutaneous disorder, accounting for 0.25 to 4% of the patients seen in Dermatology Clinics in South East Asia, and is the most common pigment disorder among Indians.[2,3] The disease affects all races, but there is a particular prominence among Hispanics and Asians.[4] Although women are predominantly affected, men are not excluded from melasma, representing approximately 10% of the cases.[5] It is rarely reported before puberty.

The exact causes of melasma are unknown. However, multiple factors are implicated in its etiopathogenesis, mainly sunlight, genetic predisposition, and role of female hormonal activity. Exacerbation of melasma is almost inevitably seen after uncontrolled sun exposure and conversely melasma gradually fades during a period of sun avoidance. Genetic factors are also involved, as suggested by familial occurrence and the higher prevalence of the disease among Hispanics and Asians. Other factors incriminated in the pathogenesis of melasma include pregnancy, oral contraceptives, estrogen progesterone therapies, thyroid dysfunction, certain cosmetics, and phototoxic and anti-seizure drugs.[6]

The hyperpigmented patches may range from single to multiple, usually symmetrical on the face and occasionally V-neck area. According to the distribution of lesions, three clinical patterns of melasma are recognized.[7] The centrofacial pattern is the most common pattern and involves the forehead, cheeks, upper lip, nose, and chin. The malar pattern involves the cheeks and nose. The mandibular pattern involves the ramus of the mandible.

Using the Wood's light examination, melasma can be classified into four major histological types depending upon the depth of pigment deposition.[8] The epidermal type, in which the pigmentation is intensified under Wood's light, is the most common type. Melanin is increased in all epidermal layers. In the dermal type the pigmentation is not intensified. It has many melanophages throughout the entire dermis.[3] In the mixed type the pigmentation becomes more apparent in some areas, while in others there is no change. Indeterminate type is where the pigment is apparent in the Wood's light, in individuals with skin type VI.[9]

This study is aimed at studying the epidemiology, clinical presentation, and precipitating and / or provocation factors associated with melasma.

Materials and Methods

The present study was carried out on the clinico-epidemiology of melasma patients between January 2009 and December 2009. Three hundred and twelve consecutive patients with a clinical diagnosis of melasma were enrolled for the study.

The demographic data regarding age at present, age of onset of melasma, sex, duration of the disease, and family history were noted. The data of different predisposing factors like sun-exposure, pregnancy, cosmetics, ovarian tumor, and other endocrinal diseases were included, and relevant investigations were carried out to rule out the same.

Clinical evaluation was done and depending upon the distributions of lesions, they were divided into centrofacial, malar, or mandibular. Wood's light examination was done to determine the histological pattern.

Results

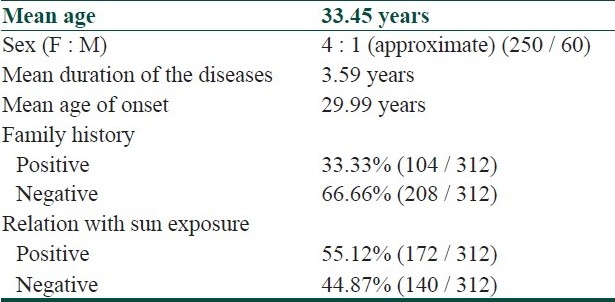

The study comprised of 312 patients of melasma; the demographic features of which are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic distribution of study population (n=312)

There were 250 females and 62 males with an age range of 14 to 54 years. It was more common in women, with a female to male ratio of 4 : 1 approximately. It mostly presented after the fourth decade of life. The mean age of onset of melasma was 29.99 years, ranging from 11 years to 49 years. Most of them sought medical treatment only 3.59 years after the appearance of their melasma. A positive family history of melasma was observed in 104 (33.33%) patients.

Of the total of 312 patients, 172 gave a history of their melasma exacerbation during sun-exposure and the remaining 140 patients did not notice any exacerbation of their disease. Out of 250 female patients, 56 (22.4%) of them reported that their disease precipitated during pregnancy and 34 (13.6%) patients explained that their disease exacerbated during pregnancy. Only 18.4% of the female patients took oral contraceptive pills during the disease process in our study, and no patients had ovarian tumors. Seventy-three patients (23.39%) used different types of cosmetics on a regular basis (at least five days in a week). There was no other autoimmune disease noted, except hypothyroidism in 20 patients out of 312 cases of melasma.

According to the distribution of lesions, three clinical patterns of melasma were observed and among these, the centrofacial type was the most common; seen in 173 (54.44%) cases. Other types noted were malar 135 (43.26%) and mandibular five (1.60%), respectively.

Under the Wood's light examination dermal was the most common pattern seen in 170 patients; and in 67 and 75 cases, the patterns were epidermal and mixed type, respectively.

Discussion

Melasma is an acquired increased pigmentation of the skin. It is a commonly seen entity in clinical practice. Few studies show that melasma accounts for 4 – 10% of the new cases in the dermatology hospital, as a referral.[10,11] Similarly it is found to be the third most common pigmentary disorder of the skin, confirmed in a survey of 2000 black people, at a private clinic in Washington DC.[12]

The average age of melasma patients was 33.45 years in our study, compared to 42.3 years, reported in a study from Singapore.[13] Melasma is more common in women. We found about 19.87% involvement of men in our study compared to 10% in a different study.[5] This study showed that the mean age of onset was 29.99 years and most patients consulted the doctor after 3.59 years of their disease, contrary to an earlier study, which noticed a later age of onset (38 years), but the duration of the disease for attending the clinic was the same.[12] A positive family history was observed, 33.33%, in the present study, which was in correlation with an earlier reported study, in which it varied from 20 to 70%.[14,15]

Multiple causative factors have been implicated in the etiology of melasma, including, ultraviolet light (sunlight), hormones (oral contraceptives), and pregnancy. There appears to be an increase in the number and activity of melanocytes in the epidermis of patients with melasma. The melanocytes appear to be functionally altered.[16] We have noticed that about 55.12% of our patients had sun exposure, which they felt was an aggravating factor. It is in great contrast to Pathak's report, which suggests that sunlight exacerbates melasma in all patients.[17]

In this study only 22.4 and 13.6% of the female patients noted pregnancy as a precipitating and aggravating factor, respectively. Only18.4% of them were taking oral contraceptives during their disease process, which was not related to the precipitating or aggravating symptoms / signs. These figures are lower than those reported earlier.[17] Few other studies have also reported a minimum relation with either pregnancy or oral contraceptives.[16,17] It appears that oral contraceptives or even pregnancy may not be a significant contributing factor in melasma. We could not find any association with ovarian tumor, but we noticed 6.41% of our patients having thyroid dysfunction. Seventy-three patients confirmed the association of cosmetics and melasma. Previously also, this association was found by Grime et al., in 1995.[6]

According to the distribution of the lesions we recognized three clinical patterns and among these, centrofacial was the most common, like other studies from India and abroad.[7,18] However, studies from Singapore and South India observed that malar distribution was the most common.[13,18] This variation of results might be due to environmental or regional differences.

Under the Wood's light examination, we found that the dermal type was the most common, in contrast to an earlier study, which suggested that the epidermal variety was the most common.[19] Even histopathologically there may not be a correlation between the findings of the Wood's light examination and the histopathological depth of the pigmentation.[20,21] The difference may be due to the non-attendance of patients with mild varieties of the disease.

Females were affected more commonly during their late third decade of life. Although we did not find the exact cause of melasma, we noticed that sun-exposure, pregnancy, and taking of oral contraceptive pills could precipitate or exacerbate the melasma. We found that some of our patient's relatives also had melasma and some of our patient's disease was associated with autoimmune disease, mainly thyroid dysfunction. These findings suggest some genetic implication in the development of melasma.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Bandyopadhyay D. Topical treatment of melasma. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:303–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.57602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasricha JS, Khaitan BK, Dash S. Pigmentary disorders in India. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:343–522. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sivayathorn A. Melasma in Orientals. Clin Drug Investig. 1995;10(Suppl 2):24–40. Q. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosher DB, Fitzpartick TB, Ortonne JP. Hypomelanoses and hypermelanoses. In: Freedburg IM, Eisen AZ, woeff k, editors. Dermatology in general medicine. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1999. pp. 945–1016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katsambas AD, Stratigos AJ, Lotti TM. Melasma. In: Katsambas AD, Lotti TM, editors. European handbook of dermatological treatments. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2003. pp. 336–41. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimes PE. Melasma: etiologic and therapeutic considerations. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1453–7. doi: 10.1001/archderm.131.12.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katasambas A, Antoniou C. Melasma: Classification and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1995;4:217–23. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapeere H, Boone B, Schepper SD. Hypomelanosis and hypermelanosis. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, editors. Dermatology in general medicine. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. p. 635. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pregnano F, Ortonne JP, Buggiani G, Lotti T. Therapeutic approach in melasma. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:337–42. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Estrada-Castanon R, Torres-Bibiano B, Alarcon-Hernandez H. Epidemiologia cutanea en dos sectores de atencion medica en Guerrero, Mexico. Dermatologia Rev Mex. 1992;36:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Failmezger C. Incidence of skin disease in Cazco, Peru. Int J Dermatol. 1992;36:29–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1992.tb02718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halder RN, Grimes PE, Mclaurin CI, Kress MA, Kennery JA., Jr Incidence of common dermatoes in a predominantly black dermatologic practice. Cutis. 1983;32:388–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goh CL, Dlova CN. A retrospective Study on the clinical presentation and treatment outcome of melasma in a tertiary dermatological referral centre in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 1999;40:455–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Resnik S. Melasma induced by oral contraceptive drug. JAMA. 1967;199:601–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vazquez M, Maldonado H, Benmaman C. Melasma in men, a clinical and histological study. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:25–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1988.tb02329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez NP, Pathak MA, Sato S, Fitzpatrick TB, Sanchez JL, Mihm MC., Jr Melasma: A clinical, light microscopic, ultrastructural and immunoflorescence study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:698–710. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pathak MA. Clinical and therapeutic aspects of Melasma: An overview. In: Fitz Patrick TB, Wick MM, Toda K, editors. Brown melanoderma. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press; 1986. pp. 161–72. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thappa DM. Melasma (chloasma): A review with current treatment options. Indian J Dermatol. 2004;49:165–76. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicolaidou E, Antoniou C, Katsambas AD. Origin, clinical presentation, and diagnoses of facial hypermelanoses. (8).Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:321–6. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hann SK, Im S, Chung WS, Kim do Y. Pigmentary disorders in the South East. (10).Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:431–8. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarvjot V, Sharma S, Mishra S, Singh A. Melasma: A clinicopathological study of 43 cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:357–9. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.54993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]