Sir,

A 26-year-old male patient reported with a complaint of frequent painful ulceration of oral cavity since 3 years. He tolerated a normal diet but frequent occurrence of oral ulcers and dysphagia limited his feed to liquid diet often. Trismus and inability to protrude his tongue was also noticed. His parents gave history of skin erosions on the back and arms at the time of birth. Since then erosions appeared all over his body at the slightest trauma and healed by scar formation. The patient was diagnosed as epidermolysis bullosa (EB) since birth. Family and personal history was non-contributory.

General examination revealed that the patient was poorly built and nourished, measured 157.48 cm and weighted 48 kg. Erosions following rupture of bullae were present all over his body mainly on the back and arms, which healed by either hypo- or hyper-pigmented scars [Figures 1 and 2]. His finger and toenails were absent. Intra orally there was gingival inflammation with punched out interdental lesions and bleeding on probing. Buccal mucosa showed multiple, irregular map, like ulcerations varying from 0.5 to 0.8 cm in size, with tissue tags at the periphery, inflamed, and edematous edges [Figure 3]. Angular chelitis was present. Complete depapillation of the tongue was noticed. Oral hygiene was poor. Dental caries was present with respect to upper right first and second premolar, lower left second molar, lower right first and second premolar (14, 15, 37, 45, 44, 45). Upper right second molar, lower left first molar, and lower right second molar (17, 36, 47) were missing following extraction due to dental caries. Biopsy specimen was obtained from back of the patient by creating a fresh lesion and was sent for light and electron microscopic examination.

Figure 1.

Complete dystrophy of toe and finger nails

Figure 2.

Hypo - or hyper-pigmented healed scar marks and ulcerations present on upper arm

Figure 3.

Intraoral ulcerations on right buccal mucosa

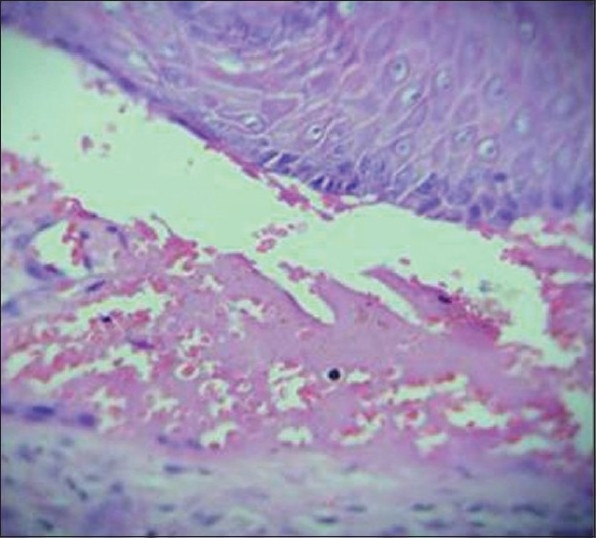

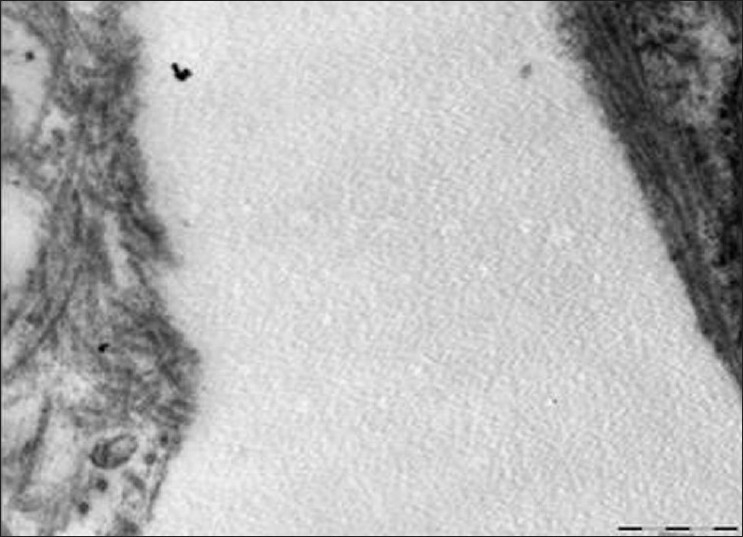

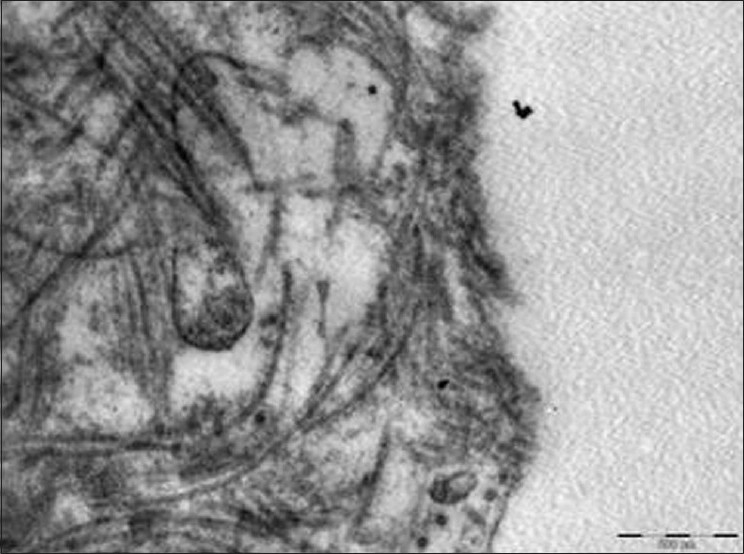

Light microscopy examination of a skin biopsy demonstrated a subepithelial cleft [Figure 4]. Electron microscopy (EM) demonstrated one area of intact dermoepidermal junction with hypoplastic hemidesmosomes. EM showed blister formation below the basement membrane zone (×30,000) [Figure 5], just beneath the level of lamina densa with diminished anchoring fibrils and normal hemidesmosomes. [Figure 6] shows floor of the blister (×30,000).

Figure 4.

Light microscopic view demonstrated a subepithelial cleft (H and E)

Figure 5.

Electron micrograph showing split below the lamina densa (×30,000)

Figure 6.

Electron micrograph showing floor of blister with collagen fibers of connective tissue

An intensive preventive program including diet counseling and oral hygiene instruction was instituted, and restoration of carious teeth was undertaken using local anesthesia. Analgesic and antibacterial mouthwash, oral prophylaxis, and periodic topical fluoride application was advised. For skin lesions, dermatological consultation was taken and topical application of fusidic acid cream was advised. Fixed partial denture was given in relation to lower right first and second molar. Patient was instructed to avoid trauma as much as possible. Patient was referred to gastroenterologist for dysphagia where barium swallow revealed proximal esophageal narrowing consistent with strictures. Patient was diagnosed as having esophageal strictures for which he underwent esophageal dilatation procedure and his condition improved. Ophthalmologic consultation showed only a refractive error without any ocular surface abnormality. Patient is under follow up.

EB is a heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by profound skin fragility with blister formation occurring spontaneously or after minor trauma. It often manifests at birth or during the first year of life. It has no ethnic, racial or gender predilection and has an incidence of approximately one in 300,000 births for recessive EB, and for dominant EB, the figure is one in 50,000.[1] At least 23 subtypes of EB have been recognized, but their precise etio-pathogenesis remain obscure (Wright et al. 1993, Fine et al. 1994). Bullae leave painful ulcers on rupturing; and healing is often followed by scarring and tissue contraction. Contractures and pseudosyndactyly of digits may result in the formation of claw-like hands. Involvement of mucosal or basement membranes can result in esophageal strictures, urethral and anal stenosis, phimosis, and conjunctivocorneal scarring. Frequently the upper esophagus may become stenotic, leading to dysphagia. Oral features include repeated blistering and scar formation leading to limited oral opening, ankyloglossia, elimination of buccal and vestibular sulci, perioral stricture, severe periodontal disease and alveolar bone resorption, atrophy of the maxilla with mandibular prognathism, increased mandibular angle, and predisposition to oral carcinoma. There have also been reports of enamel hypoplasia,[2,3] nail and hair dystrophy, and alopecia in affected individuals. Although major advances have been made recently in elucidating the molecular basis of EB, EM still is the gold standard for classifying EB into its major categories.

On the basis of the level of skin cleavage leading to blister formation and electron microscopic (EM) examination, EB has been divided into three broad categories: Simplex forms (in which blisters develop intra epidermally at the level of the basal keratinocytes above the basement membrane BM), junctional forms (in which blisters develop within the BM), and the term “dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa” (DEB) is used to describe forms of the disease in which blisters form beneath the BM. Our patient was diagnosed as DEB with severe oral and skin involvement.

Electron microscopy is gold standard for diagnosis of EB, but it has some limitations like inappropriate handling of the biopsy specimen or problem with fixation can induce artifacts which results in error of diagnosis.[4] Electron microscopic examination is a relatively expensive and not readily available to most dermatopathologists performing routine diagnosis. Recently, immunoreagents have been developed to map antigens in the basement membrane zone (BMZ). Some of these reagents are reactive in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections, and offer a potential diagnostic alternative to EM in the routine diagnosis of EB. Monoclonal antibody studies can be used to confirm the classification established by electron microscopy and immunofluorescence antigenic mapping.

In addition to repeated oral blistering and ulcer formation, studies have shown that the caries prevalence and gingivitis among individuals with dystrophic EB and junctional EB is significantly higher than among healthy people.[5] In our case also multiple carious teeth were found and few teeth had been extracted due to deep caries and pain.

Exact causes of EB remain obscure and, accordingly, there is no specific treatment; only palliative therapy exists. Treatment involves a multidisciplinary approach involving dermatologist; oral physician and general physician. Surgical reconstruction is sometimes indicated to improve function and appearance. Maintenance of the dentition is imperative since prosthetic replacement is usually contraindicated (Carroll et al., 1983).

Preventive strategies must be aimed at plaque-related diseases of dental caries and periodontal disease.[6] Diminished mouth opening and progressive obliteration of the labial sulcus make oral hygiene difficult. Physical removal of bacterial plaque may be supplemented with chemical inhibition by the use of chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash daily. The use of fluoride to prevent dental caries is another vital component in prevention. Neutral pH sodium fluoride mouthwashes are useful, while acidic fluoride preparations cause discomfort when oral ulceration occurs. Nutritional advice may be indicated as coarse foods are not well-tolerated, and a high caries rate is often the norm.[7]

Restorative needs may be undertaken under local anesthesia if only small and relatively atraumatic procedures are needed. Extensive dental treatments are better conducted under endotracheal intubation or deep sedation.[8]

EB is incurable and the treatment is palliative and non-specific. Dermatologist and dentists should provide a better quality of life for these patients. Dental treatment should be aimed at improving oral health, and it is important that the natural dentition be maintained as it helps the patient socially, psychologically, and nutritionally.

References

- 1.Davidson BC. Epidermolysis bullosa. J Med Genet. 1965;2:233–42. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2.4.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright JT, Johnson LB, Fine JD. Development defects of enamel in humans with hereditary epidermolysis bullosa. Arch Oral Biol. 1993;38:945–55. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(93)90107-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirkham J, Robinson C, Strafford SM, Shore RC, Bonass WA, Brookes SJ, et al. The chemical composition of tooth enamel in junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Arch Oral Biol. 2000;45:377–86. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(00)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puvabanditsin S, Garrow E, Kim DU, Tirakitsoontorn P, Luan J. Junctional epidermolysis bullosa associated with congenital localized absence of skin, and pyloric atresia in two newborn siblings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:330–5. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.105480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright JT, Fine JD, Johnson L. Dental caries risk in hereditary epidermolysis bullosa. Pediatr Dent. 1994;16:427–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winter G. Dental problems in epidermolysis bullosa. In: Priestly GC, Tidman MJ, Weiss JB, Eady RA, editors. Epidermolysis bullosa: A comprehensive review of classification, management, and laboratory studies. Crowthorne, Berkshire, UK: Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Association; 1990. pp. 21–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright TJ, Fine JD, Johnson L. Hereditary epidermolysis bullosa: Oral manifestations and dental management. Pediatr Dent. 1993;15:242–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright TJ. Comprehensive dental care and general anesthetic management of hereditary epidermolysis bullosa: A review of 14 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;70:573–8. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90401-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]