Abstract

This study tested a hypothesized social interaction learning (SIL) model of confidant support and paternal parenting. The latent growth curve analysis employed 230 recently divorced fathers, of which 177 enrolled support confidants, to test confidant support as a predictor of problem solving outcomes and problem solving outcomes as predictors of change in fathers’ parenting. Fathers’ parenting was hypothesized to predict growth in child behavior. Observational measures of support behaviors and problem solving outcomes were obtained from structured discussions of personal and parenting issues faced by the fathers. Findings replicated and extended prior cross-sectional studies with divorced mothers and their confidants. Confidant support predicted better problem solving outcomes, problem solving predicted more effective parenting, and parenting in turn predicted growth in children’s reduced total problem behavior T scores over 18 months. Supporting a homophily perspective, fathers’ antisociality was associated with confidant antisociality but only fathers’ antisociality influenced the support process model. Intervention implications are discussed regarding SIL parent training and social support.

Keywords: fathers, divorce, social support, problem solving, parenting, observation

Childrearing can be challenging in socially disadvantaged environments and with stressful events like divorce that can interfere with parenting (Ceballo & McLoyd, 2002; Green, Furrer, & McAllister, 2007). Availability of quality social support can mitigate effects of stress on parenting (Leinonen, Solantaus, & Punamäki, 2003). Conversely, social isolation and the lack of social resources are key factors that lead to compromised parenting (Castillo, 2009).

With federal fatherhood initiatives, more attention is being paid to the impact of social support on paternal involvement for adolescent fathers (Fagan, Bernd, Whiteman, 2007), socially disadvantaged nonresidential fathers (Castillo & Fenzl-Crossman, 2010; Coley & Hernandez, 2006), and divorced fathers (DeGarmo, Patras, & Eap, 2008). Social networks become increasingly important over time and become the principal source parenting support for single parents (Belsky, 1984). Evidence also shows that marital separation can lead to atrophy in social networks with divorced individuals’ networks shorter in duration and lower in density than married persons (Hurlburt & Acock, 1990; Sprecher et al., 2006). For parenting needs, divorced fathers depend upon new partners and extended kin networks more heavily than do their divorced mother counterparts (Stone, 2002). Given the relevance of support for fathers, it is important to understand support processes. Further, the majority of prior parenting research has focused on social support for disadvantaged single mothers (Andresen & Telleen, 1992).

In this paper, we extend prior research in important ways. The majority of divorced father research has focused on fathers’ involvement with children measured as amount or quality of contact and less so on ways in which fathers’ parenting behaviors. Second, studies involving formal and informal support have focused on perceived support availability and less so on support transactions. Fathering support research has focused on two general categories; informal perceived support, and formal occupational or support services (Castillo, 2009; DeMaris & Greif, 1997). Two recent studies measured reports of support for specific fathering needs such as childcare, transportation, or advice (Castillo & Fenzl-Crossman, 2010; DeGarmo et al., 2008).

Here, we employ a social interaction learning model focusing on interactions between divorced fathers and their confidants with regard to support and problem solving discussions. From this perspective, it is presumed that key persons within the social environment shape and support patterns of behavior that contribute to healthy or dysfunctional adjustment. For youngsters, parents and peers are seen as being most influential. For divorced parents, confidants assume this role and can include extended family, co-workers, friends, and lovers. Using established behavioral paradigms, fathers and confidants in the present study are assessed during discussions of stressful issues facing the father including parenting.

Social Interactional Learning (SIL) View of Support and Parenting

The present theoretical framework is a social interaction learning (SIL) model of social support, problem solving, and parenting (Forgatch, 1989; Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1997) applied to the context of fathers after divorce. We propose that quality advice and emotional support provided by adult confidants will yield effective problem solving outcomes, and problem solving outcomes will promote effective parenting. Confidants, their personal characteristics, and quality of their social interactions are predicted to affect problem solving outcomes that either promote well-being or become part of stress-maintenance processes (Patterson & Forgatch, 1990).

The SIL perspective focuses on observed interchanges between people rather than reported appraisals that generally assess support satisfaction or perception that support is available. Perceived support is typically demonstrated to be contingent on problems and is presumed to have a stress-buffering or moderating effect on stressors. Support behaviors refer to the beneficial transactions and interactions within networks (Burleson, 1990). Appraisals are poorly understood because most studies have documented that support receipt is either associated with poor adjustment or, at best, leaves the recipient no better off than having reported no support received (Schwarzer & Leppin, 1991).

Testing an SIL model, a prior cross-sectional study with single mothers showed that effects of observed confidant support on parenting practices were mediated by the quality of problem solving outcomes achieved during problem solving discussions (Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1997). Findings supported a sequence from support behaviors to problem solving outcomes to effective parenting practices for divorced mothers. We extend the model here to test a longitudinal sequence for divorced fathers and their confidants.

Antisociality and Individual Characteristics

Support provider and recipient characteristics influence the support process. A selection or homophily perspective (Kandel, Davies, & Baydar, 1988) suggests that antisocial fathers may select confidants who are similarly antisocial. Instead of serving as a resource, antisocial or highly distressed confidants can lead to poor outcomes, including increased stress (Burleson, 1990). Conversely, prosocial confidants may provide more appropriate and effective feedback, support and guidance. Testing the SIL model, Patterson and Forgatch (1990) showed that high rates of maternal irritability observed with confidants during problem solving discussions led to poor problem solving outcomes. We hypothesize that antisociality of fathers and confidants will predict lower levels of confidant support and lower levels of problem solving outcomes.

Antisociality is particularly relevant to parenting of divorced fathers. For clinically-referred children, Pfiffner, McBurnett, and Rathouz (2001) found that father-absent families, compared with father-present families, had higher levels of antisociality in children, mothers, and fathers. Antisociality among mothers and children was highest if the father could not be located or recruited, and this problem was not mitigated by presence of stepfathers. Studies of adolescents (Jaffee, Moffitt, Caspi, & Taylor, 2003) and younger children (DeGarmo, 2010) have shown that involvement of nonresidential fathers has beneficial impact on children’s developmental outcomes, however, that benefits of father involvement are conditioned by antisociality. These findings are consistent with Patterson’s (1982) family coercion model suggesting that parent antisociality contributes to children’s poor developmental outcomes via over-learned and reinforced patterns of negative interaction between parents and children.

Support provider gender and status as romantic partner are also factors identified with the quantity and quality of support. Females generally provide more support than do males and females tend to be more socially skilled (Sarason, Sarason, Hacker, & Basham, 1985). However, marital studies have shown that women are more likely than men to engage in negative behaviors during problem solving and men are more likely than women to withdraw from negative exchanges (Markman, Silvern, Clements, & Kraft-Hanak 1993). For single mothers, Forgatch and DeGarmo (1997) found that females provided more positive support behaviors than males, but mothers interacting with new romantic partners achieved better problem solving than those interacting with family members or friends. We predict females will provide greater levels of support behaviors and fathers with new partners will yield better problem solving outcomes.

Study Hypotheses

Based on findings above, we formed the following hypotheses (H1–H4):

H1. Confidant Characteristics

Female confidants will exhibit higher levels of support behaviors. Romantic partner status will be associated with better problem solving outcomes.

H2. Longitudinal Support Process

Support behaviors will predict better problem solving outcomes. Problem solving outcomes, in turn, will predict decreased levels of coercive fathering. Coercive fathering in turn will be associated with increases in children’s problem behaviors.

H3. Homophily Hypothesis

Antisocial characteristics of fathers will be associated with antisocial characteristics of confidants.

H4. Antisociality Hypothesis

Antisocial characteristics of fathers and confidants will be associated with lower support and problem solving; fathers’ antisociality with poor parenting.

Method

The present study consists of 230 fathers from the Oregon Divorced Father Study (ODFS) recruited to participate in a study focusing on father and child adjustment to divorce. A unique aspect of the study was to evaluate adjustment for divorced fathers including a range of categories specifying father-child contact including custodial and noncustodial fathers. All divorced fathers with children in the focal age range were eligible for selection within the county sampling frame. Fathers were recruited through public divorce court records. Eligible fathers had a boy or girl focal child between the ages of 4 and 11 and had obtained a divorce decree within 24 months. Court records were screened, if more than one child was eligible within a family, we used random selection for the focal child.

After selecting eligible records, fathers were invited to participate with their child through a recruitment letter explaining the study and how they were selected. Informed consents were obtained at the first center visit after explaining the study and potential risks and benefits. Among the 230 enrolled fathers, 180 (78%) chose to and were able to enroll the focal child. For comparison of nonparticipants, custody status was defined as legal custody reported in the court records. We found that 92% of full-custody and 95% of shared-custody fathers enrolled the targeted focal child, while 41% of no-custody fathers enrolled their focal child. Therefore, not all full- and shared-custody fathers had their children participate in the center assessments. However, all fathers, including no custody, completed questionnaires and interviews regarding their children’s behavior and their own parenting. The large majority of fathers (96%) reported contact with the focal child with in-person visitation, email, telephone, or correspondence.

All fathers were invited to enroll an adult confidant to study support processes. One-hundred seventy-seven (77%) fathers enrolled a confidant, 26 fathers could not identify a support person and reported no support providers in their lives, and 27 reported on support providers and a confidant relationship but did not enroll a confidant. No significant differences were obtained for parenting indicators, child behavior problems, and antisociality when comparing fathers with and without confidants. Confidants’ ages ranged from 17.7 to 83.0 (M = 38.6, SD = 12.7), 70% were female, 12% self-identified as a racial/ethnic minority. Confidant relationships were broadly distributed as fathers’ own mother (11%), own father (2%), co-workers (6%), friends (15%), sons (1%), daughters (3%), other relatives (7%), former spouses (4%), former relatives (1%), new romantic partners (50%), and professionals (e.g., priest/minister, counselor) (1%).

Fathers’ age ranged from 22.9 to 63.4 years (M = 37.8, SD = 7.7), education from 1 (< 8thgrade) to 13 (advanced doctorate) (M = 7.2, SD = 2.9), and income from 1 (< $5K) to 10 (> $100K) (M = 5.4, SD =2.2). Children’s age ranged from 4.0 to 12.0 (M = 7.6, SD = 2.0), 47% were girls. Fathers self-identified as European American (87%), multiracial (5%), Hispanic (4%), Native American (2%), African American (1%), and Asian (1%). Children were reported as European American (83%), multiracial (14%), Hispanic (1%), Native American (1%), and less than one percent African American and Asian. The county sampling frame consisted of 37% no-, 54% shared-, and 10% full-custody. The ODFS comprised 32% no-, 53% shared-, and 14% full-custody fathers. Originally, 867 recruitment letters were mailed of which 572 were located and eligible for an overall participation rate of 40% (35% no-, 41% shared-, and 55% for full-custody). No differences were found between participants and nonparticipants on neighborhood characteristics from census tract and geo-coded police call response data near the father’s address (e.g., unemployment rates, proportion homeownership, poverty rates, racial makeup, and police call frequency and severity ratings). To generalize to the county level, sample weights were obtained as correction factors for selection bias using plausibly correlated characteristics procedures outlined by Braver and Bay (1992) for court records-based studies adjusting for differential participation, eligibility, and location rates by custody and potential threats of selection bias (computations provided in DeGarmo et al., 2008).

Assessment Procedures and Measures

Multiple method data were collected for the study. Longitudinal data were collected at three waves: Baseline, Time 1 (T1), a 9-month follow up (T2), and an 18-month follow up (T3). Retention rates for were 84% and 82% respectively for T2 and T3 with no differential rates of attrition (n = 83%, 84%, and 77%, respectively for full, shared, and no custody fathers).

Data were collected during two center visits, one with the father and confidant and one with father and focal child. Participants completed face-to-face interviews, paper and pencil questionnaires, computer-assisted interviews, and self-administered questionnaires. Data from direct observations were obtained from structured interaction tasks. Participants and teachers were paid approximately $25 an hour for their time. Each center visit was approximately 2.5 hours. All participants were provided childcare, transportation, and a meal if requested.

Observational data for the father-confidant support and problem solving were obtained from two 7-minute problem solving discussions; a personal issue and a parenting issue selected by the father. Data for parenting behaviors were obtained from a total of 24 minutes of interaction scored across 4 structured tasks during the father-child visit: 5 minute refreshment task, 7 minute problem solving discussion regarding a current conflict issue, 7 minute play task, and 5 minute academically challenging teaching task. All interactions were scored by trained coders using the Family and Peer Process Code (FPP: Stubbs, Crosby, Forgatch, & Capaldi, 1998). Behavior Kappa = .79 T1, .79 T2, Affect Kappa = .80 T1, .78 T2.

Confidant Support Behaviors was a latent construct with three T1 indicators. Two scales were coder ratings of interpersonal support provided during the parenting and personal problem solving discussions. Each scale consisted of 12 Likert-type items rated on 5- and 7-point scales scored to reflect higher levels of support (e.g., gave advice and guidance, showed genuine interest, displayed emotional support, reframed things positively, confidant was supportive). Three items were semantic differentials (e.g., critical-encouraging, rejecting-accepting, disrespectful-respectful). All items were rescaled on a range of 1 to 5 and averaged, α = .92 and .91 respectively for parenting and general issue, inter-rater intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was .72 and .75, respectively. The third indicator was comprised of four FPP indicators: frequency of positive support behaviors directed to the father, rate-per-minute, mean duration, and frequency proportion of positive behaviors relative to all other behaviors (α = .88). The resulting FPP factor score was previously validated (DeGarmo & Forgatch, 1997).

Problem Solving Outcome was a scale consisting of 11 items rated from 1 (very untrue) to 7 (very true) at Time 1. Sample items were: problem was defined in a way to facilitate resolution, at least one good solution was proposed, a plan was developed, several good solutions were proposed, extent of resolution, likelihood of follow through, α = .93 and .95, respectively for parenting and personal discussions (ICCs = .69 and .73).

Coercive Fathering was an observation-based latent variable with two previously validated indicators (DeGarmo et al., 2008), coercive parenting and prosocial parenting measured at Times 1 and 2. To compute construct scores combining count frequencies and Likert ratings, each construct indicator was rescaled to a continuous common metric (0 to 1) and then averaged. The first coercive parenting indicator was computed from the mean of two variables. Harsh discipline ratings comprised of 5 globally-rated items on a scale of 1 (very untrue) to 5 (very true). Items were overly strict, authoritarian, expressed hostility during discipline, used nagging, hovered too closely, and used inappropriate discipline (α = .86 and .88 at Times 1 and 2). Father total aversive was a behavior cluster score of FPP father-initiated behaviors directed to the child that included physical and verbal behaviors (e.g., physical aggression, verbal aggression, negative tease, negative interpersonal, physical attack, and verbal attack). The second parenting indicator was observed prosocial parenting, the mean of two globally-rated scales. Positive involvement was obtained from 14 items rated after each father-child interaction task. Items included: extent to which parent treated the child with warmth, empathy, affection, and respect, maintained good eye contact and interactive posture (α = .94 and .95 at Times 1 and 2). Skill encouragement was ratings of fathers’ ability to promote children’s skill development through contingent encouragement and scaffolding strategies observed during the teaching and construction play tasks. The scale includes 11 items, such as: breaks task into manageable steps; reinforces success; prompts; corrects appropriately (α = .92 and .91 at Times 1 and 2).

Child Problem Behaviors was the father-reported Total Problems T score from the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA: Achenbach, & Rescorla, 2000; 2001). Subscales for the total problems score include internalizing, externalizing, thought problems, attention problems, and other behavior problems (α = .84, .86, and .83, respectively across time for ASEBA problem behavior subscales).

Antisocial Personality was measured at Time 1 using 3 validated instruments. The first indicator was the 20-item Acting Out subscale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-TRI (MMPI-TRI: Swanson, Templer, Streiner, Reynolds, & Miller, 1995). Statements were rated true or false and then summed (e.g., was suspended from school; when people do me wrong I feel I should pay them back; when I was young I stole things; at times I feel like picking a fist fight; I can easily make people afraid of me (α = .82 for fathers and .77 for confidants). The second measure was the 12-item Agreeableness subscale (NEO-A) from the NEO-Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI: Costa & McCrae, 1995). Rated from 5 (disagree) to 1 (strongly agree), sample items were: I try to be courteous of everyone I meet; most people I know like me; I often get into arguments with my family and co-workers; if I don’t like people I let them know it (α = .82 for fathers and .76 for confidants). The NEO-A has been validated with the DSM IV as a marker of antisocial personality for men scoring low in agreeableness. The third indicator was a Substance Use construct of 4 scores rescaled 0–1 and averaged: Alcohol Use: (a) frequency (e.g., How often do you drink, wine, beer, hard liquor, or any other alcoholic beverage?, 0 (never use) to 12 (three or more times a day), (b) quantity (e.g., how often do you have as many as 5 or 6 drinks? … 3 or 4 drinks? etc.), 1 (never) to 5 (nearly every time), and (c) Risk, sum of 4 “yes-no” items (e.g., become argumentative when drinking?); Smoking frequency (e.g., how many cigarettes or cigars a day?); Marijuana frequency (e.g., how often do you smoke marijuana?, 0 (never tried) to 12 (three or more times a day)); and Hard drug use, the average of 8 items, 0 (never tried) to 12 (three or more times a day) including cocaine, speed, LSD, heroin, etc.

Control Variables

Confidant relationship type was coded 1 for friend/coworker, 2 for relative or former relative, and 3 for intimate partner. Sex of confidant was 0 for female, 1 for male. Age of child was computed in years from date of birth. Sex of child was coded 0 for girls and 1 for boys. Fathers’ reported monthly contact was the mean number of weekday and weekend days per month of contacts with the child and the number of overnight stays and visits during the typical school year. The mean number of days of contact per month were 25.71 (SD = 6.72), 15.39 (SD = 6.60), and 11.91 (SD = 7.39) for full-, shared-, and no-custody fathers, respectively. The mean overnight stays were 25.50 (SD = 7.19), 12.41(SD = 6.31), and 6.91(SD = 6.04), respectively.

Analytic Strategy

For mean comparisons by relationship and gender, we employed standard normal Analysis of Variance and t tests. For the main support process hypothesis we employed structural equation path modeling (SEM) using the Mplus 6.1 program (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Along with mismatching method indicators for the SEM path model, we minimized potential specification error by using time-ordered model specification for the longitudinal data. First, confidant support and problem solving at T1 were specified as predictors of change in fathers’ parenting from T1 to T2. Change in fathers’ parenting in turn was specified as predictors of change in child behavior problems from T1 to T3 specified as a linear growth model. Furthermore, to minimize potential monomethod or reporter bias, we mismatched indicators of latent variables in the longitudinal prediction model. For example, observational data focusing on father-confidant interactions were predictors of father-child interactions scored by different coders and collected during separate center visits as well as different coders across time. The dependent variable was then a validated measure of father-reported child behavior problems.

As a special case of SEM, we specified latent growth models (LGM) for the three-wave repeated measure of child behavior problems. Growth models provide advantages for modeling developmental change over time and are a special case of multi-level modeling in the SEM framework in which repeated measure outcomes at Level 1 are nested within individuals at Level 2. At Level 1, individual differences or variation in levels of child problem behaviors are estimated as well as the increases or decreases in problem trajectories as growth. The individual intercepts and slopes are then summarized as latent variable factor components at Level 2 representing the sample means and variances for an intercept factor and a growth factor. Specifically, child problem behaviors were modeled as a baseline intercept and as linear growth or slope factor. This was obtained by fixing the three random intercept factor loadings at 1 for T1, T2, and T3, and by specifying the chronometric time weights for the slope factor at 0, 1, and 2 (see Biesanz, Deeb-Sossa, Papadakis, Bollen, & Curran, 2004 for a discussion).

Little’s test of missing data revealed the longitudinal SEM covariance data could be assumed missing completely at random [Little’s MCAR Chi-Square (384) = 412.91, p = . 15], indicating missing values were randomly distributed across all observations and missingness were not dependent on observed values of the dependent variables. Following recommendations, data were then estimated using full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) which uses all available information from the observed data. FIML estimates are computed by maximizing the likelihood of a missing value based on observed values in the data (Jeličić, Phelps, & Lerner, 2009). FIML provides more statistically reliable standard errors than mean-imputation, list-wise, or pair-wise models. Individuals with one time point contribute nothing to the likelihood of estimates and are effectively excluded from longitudinal analyses (Brown et al., 2008).

Findings

Means and standard deviations for indicators of confidant support and problem solving are presented in Table 1 by confidant relationship types. Hypothesis 1 stated females would be higher on support behaviors and romantic partners would have higher problem solving outcomes. Contrary to expectations, romantic partners did not have higher support behaviors or problem solving outcomes. Findings provided mixed support for gender with female confidants scoring higher than males on the support behaviors factor score (M = .10, SD = 1.02 for females and M = −.38, SD = .81 for males, t = 2.42, p = .02). However, female confidants were not rated higher on the interpersonal support scale during the respective problem solving discussions (M = 5.19, SD = .96 and M = 5.09, SD = .98, respectively for female and male confidants, and M = 5.29, SD = .97 and M = 5.36, SD = .90, respectively for females and males).

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations, and Confidant Type Contrasts for Observed Support and Problem Solving Outcome Indicators

| (1) Friend/ Coworker | (2) Relative/ Former Relative | (3) Romantic Partner | Significant Contrasts | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | F(2) | ||

| Observed Confidant Support | ||||||||

| Coder Ratings - Parenting Problem | 5.21 | (0.93) | 5.25 | (0.80) | 5.11 | (1.06) | 0.32 | n.s. |

| Coder Ratings - Personal Problem | 5.35 | (0.81) | 5.40 | (0.79) | 5.22 | (1.07) | 0.63 | n.s. |

| FPP Support Behaviors Factor Score | −0.16 | (1.17) | −.22 | (0.70) | 0.11 | (1.04) | 1.68 | n.s. |

| Problem Solving Outcomes | ||||||||

| Parenting Problem | 4.11 | (1.19) | 4.03 | (1.41) | 3.97 | (1.25) | 0.18 | n.s. |

| Personal Problem | 3.71 | (1.38) | 4.16 | (1.31) | 4.24 | (1.34) | 2.01 | n.s. |

p < .001;

p < .001;

p < .05;

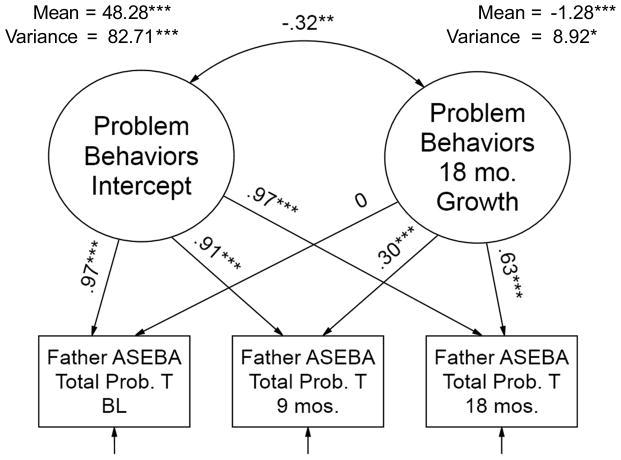

In the next step of the analyses we specified an SEM path model to test Hypothesis 2 stating that confidant support would predict better problem solving, which in turn would predict fathers’ parenting and this in turn would predict change in child behaviors. The first step in the LGM growth analysis was to estimate the unconditional model which describes individual and sample patterns of change in child problem behaviors. The longitudinal means and standard deviations for the ASEBA T scores are provided in Table 2 along with fathers’ coercive and prosocial parenting indicators. The unconditional model specified an initial status factor and a linear growth factor. Results are shown in Figure 1 in the form of standardized beta paths. The LGM provided excellent fit to the observed data with a nonsignificant chi-square minimization, a comparative fit index (CFI) above .95, a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) below .10, and a chi-square ratio (χ2/df) below 2.0 [χ2(1) = .22, p = .64; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00; χ2/df =.22]. The estimated mean intercept level for the sample at baseline was significantly different from zero (M = 48.28, p < .001) and there were significant individual differences at baseline (VAR = 82.71, p < .001). Over time, children showed decreases in problem behaviors as a sample (M = −1.28, p < .001) and showed significant individual differences (VAR = 8.92, p =.02). The significant growth variance indicated that the sample was characterized by children with decreasing trajectories of problem behaviors as well as children with increases in problem behaviors following divorce of their parents.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for Fathering Indicators and Child Behavior Over Time.

| Baseline | 9 mos. | 18 mos. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | ||||

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | |

| Father’s Parenting Behaviors | ||||||

| Observed Coercive Indicator | .68 | (.11) | .89 | (.12) | ||

| Observed Prosocial Indicator | .83 | (.09) | .82 | (.11) | ||

| Child Total Behavior Problems | ||||||

| ASEBA T score | 48.23 | (9.56) | 46.96 | (9.87) | 46.05 | (9.36) |

Note: ASEBA is Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment.

Figure 1.

Unconditional latent variable growth model for change in child’s total problem behaviors T score from baseline to 18 months. Paths are standardized solution. χ2 = .22, df = 1, p = .64, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00; χ2/df = .22. ***p < .001; **p < .001; *p < .05.

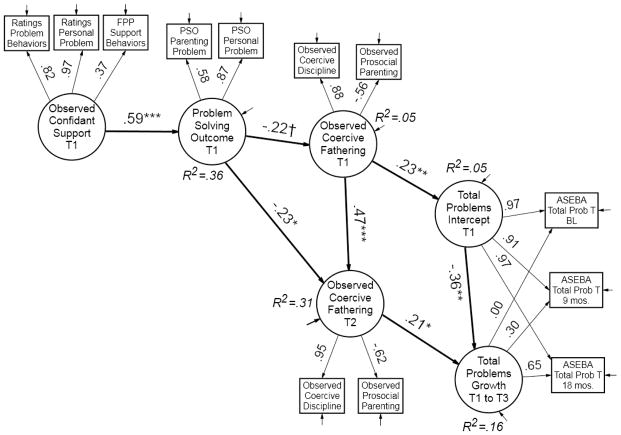

The next model entered time ordered hypothesized predictors of growth in child behavior problems. Because change in fathering behaviors was assessed at two waves, change in fathering was models as an auto-regressive latent variable at Time 2 controlling for Time 1. Change in child behavior was models as the LGM shown above. The model was evaluated with simultaneous and stepwise entry of covariates including confidant relationship type, gender, and amount of contact with children. Results of the longitudinal path model are shown in Figure 2 using standardized regression paths with nonsignificant paths constrained to zero from left to right. Control covariates are not displayed for clarity. The data supported H2, extending prior cross-sectional studies. From left to right, confidant support behaviors predicted higher levels of problem solving outcomes (β = .59, p < .001), problem solving outcomes at T1 in turn were associated with decreases in coercive fathering from T1 to T2 (β = −.23, p = .05). Increases in coercive fathering behaviors in turn predicted increases or growth in child behavior problems (β = .21, p = .02). Sixteen percent of the variance in growth in problem behaviors was explained.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal test of confidant support and problem solving as predictors of change in fathers’ parenting and growth in child problem behaviors. χ2 = 119.27, df = 59, p = .00, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .06; χ2/df = 2.02. ***p < .001; **p < .001; *p < .05; †p <.10

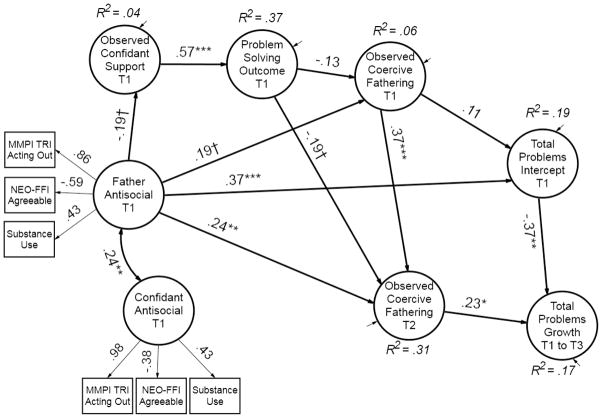

The last step of the analyses first tested the Hypothesis 3 homophily perspective stating father and confidant antisociality would be correlated and tested Hypothesis 4 stating that antisociality would predict the support and problem solving process. Results are shown in Figure 3. For visual clarity, only new information for the antisociality factors were displayed, factor loading measurement paths from previous models were not displayed. Supporting the homophily selection perspective, father and confidant antisociality constructs were significantly correlated .24, p = .01. Surprisingly, confidant antisociality did not contribute prediction to support behaviors or problem solving outcomes as expected. Fathers’ antisocial characteristics provided marginal influence on the support process. Father antisociality predicted lower support (β = −.19, p =.06), increases in fathers’ coercive parenting (β = .24, p = .01), and father reported problem behaviors at baseline (β = .37, p < .001). Furthermore, entering father and confidant antisociality reduced the impact of problem solving outcome on change in fathers’ coercive parenting to β = −.19, p = .06. Therefore, controlling for father and confidant antisociality, the hypothesized longitudinal sequence remained significant at or below a p .06 significance level.

Figure 3.

Longitudinal test of confidant support and problem solving as predictors of change in fathers’ parenting entering father and confidant antisociality. χ2 = 215.91, df = 135, p = .00, CFI = .92, RMSEA = .05; χ2/df = 1.59. Paths are standardized solution.***p < .001; **p < .001; *p < .05; †p <.10

Discussion

The present study advances prior models of social support for parenting by focusing on confidant support behaviors and problem solving outcomes as predictors of divorced fathers’ observed parenting practices. We extended SIL models and findings for prior studies of divorced mother families by testing a hypothesized longitudinal model within a county representative study of divorced father families. The results replicated a sequence delineating contributions of confidant support behaviors to problem solving outcomes observed during discussions of personal and parenting issues raised by the divorced fathers. Moderate levels of explained variance were obtained for problem solving outcomes, parenting practices, and child behaviors.

Divorced fathers’ antisocial characteristics were significantly associated with their confidant’s antisocial characteristics, as hypothesized. Fathers’ antisociality, however, and not confidant antisociality, displayed influence on the support process. Although the data were not experimental, and therefore, causality cannot be inferred, we chose temporal ordering of the longitudinal data and factor indicators mismatched by coders or data collection method to minimize specification error or potential monomethod bias.

Over two-thirds of the confidants were female. Consistent with prior research, females displayed higher levels of coded support behaviors but they did not exhibit higher levels of rated interpersonal support as expected. Thus, hypotheses were not supported regarding expected differences among confidant relationship types. In fact, there were no differences for romantic partners relative to friends or relatives for the fathers. Prior studies with single mothers showed that romantic partners exhibited better problem solving outcomes in interactions with mothers (Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1997) and friends displayed higher levels of support (DeGarmo & Forgatch, 1997). It was reasoned that friends may display a higher frequency of more unconditionally supportive behaviors while romantic partners may be more intimate and able to display relatively more negative behaviors along with more conditional support. Romantic partners may be more familiar with the circumstances related to selected topics by the parent.

Gender of divorced parent may play a factor in this lack of replication in terms of communication skill or perhaps problem identification and help seeking behaviors of parents. For example, consistent with prior studies of help seeking, Redmond, Spoth, and Trudeau (2002) found that mothers engaged in more formal and informal support seeking for parenting than did fathers in a large community sample of parents of sixth graders. In a recent innovative study of problem solving among same-sex and cross-sex, married and unmarried couples, Baucom, McFarland, and Christensen (2010) found that females made demands at higher levels than men and that men withdrew at higher levels, consistent with cross-sex marital studies. For all couples, they found partners were more likely to be in a demanding role during their own topic than their partners’, and polarization was greater in female-selected topics than male selected topics. More content-focused analysis of the selected issues and future research blocking by gender of parent and marital status is needed to address these questions for divorced parents and parenting needs.

Prevention and Practice Implications

Quality involvement of resident and non-resident fathers benefits children’s developmental outcomes. Antisociality and coercive parenting condition this beneficial effect. Given the present findings, however, we underscore results that replicated prior research with single-mother confidant models. Confidant support and problem solving processes were associated with better parenting of divorced fathers.

Divorce places a parent at the epicenter of many minor, chronic, and potentially devastating events. In fact, recent national evidence indicates that health differentials between divorced and married adults have actually increased over the last several decades (Liu & Umberson, 2008). For fathers, changing roles, loss of social support, sole or partial parenting, and separation from children explain observed declines in mental and physical health from a divorce crisis model (Braver, Shapiro, & Goodman, 2006). There is a need for more specified work on translating programs and intervention technologies demonstrated effective for mothers and two-parent families for fathers for whom relatively few evidence-based programs exist. Naturalistic support providers could be an effective focus for enhancing such interventions. Divorced fathers are likely to benefit from parent training programs designed to address stress management, problem solving skills, and effective noncoercive parenting strategies. The data also imply fathers are also likely to benefit from social support interventions with adult support providers (Lakey & Lutz, 1996).

The Oregon Model of Parent Training (PMTO: Patterson, 2005) is a theory-based evidence based program from an SIL model, A critical finding from a stepfamily study was that PMTO produced a larger effect size on improved parenting behaviors for stepfathers compared to biological mothers (DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2007). An untested assumption is that PMTO would also greatly benefit divorced fathers and in turn their children. Additionally, recent attention to never married, cohabiting, nonresidential, and underemployed fathers has shown that institutional supports are important for fathers’ compliance with child support obligations and establishing support orders (Castillo, 2009). Given that fathers are less likely to seek formal supports for parenting, formal support services may also play an important role in prevention programs for shared custody and nonresidential divorced fathers.

Perspectives focused on the beneficial and positive experiences associated with childrearing may be helpful in delivering prevention programs to antisocial fathers. Because of their desire to stay involved with their children, effective programs may benefit from father-oriented components increasing men’s awareness of child-centered needs, coparenting, and influence of fathers’ behaviors (Brotherson, Dollahite, & Hawkins, 2005). Presently there are few evidence based programs for divorced or nonresidential fathers. Two examples are the Dads for Life (DFL) program (Braver, Griffin, & Cookston, 2005) and the Strengthening Father Involvement (SFI) program (Cowan, Cowan, Pruett, Pruett, & Wong, 2009). Relevant for antisociality, each have focused on the reduction of coparenting conflict. Dishion, Owen, and Bullock (2004) state that it is likely that deviant fathers are underrepresented in prevention research and currently little research exists on how antisocial fathers respond to parenting interventions. Examples from clinical treatment work with maltreating and abusive fathers have shown that fathers are more responsive to interventions pointing out the welfare and needs of the children as a focal point for addressing harmful interactions with spouses and children (Scott & Crooks, 2004). Extending Dishion and colleague’s prevention work with deviant peers (Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003), social support interventions with confidants and support providers in the adult domain could be effective for addressing antisocial fathers’ coping abilities.

Although some level of generalizability could be drawn from the present data, several limitations need to be noted. The sample was relatively small and was limited in racial and ethnic diversity. Longitudinal multiple method data including direct observation of support transactions and parent-child interactions were an advantage. However, larger and more regionally diverse samples are needed to replicate the importance of support for fathering using samples in culturally diverse settings. Prior studies have shown variation in challenges for residential and nonresidential fathers from diverse neighborhoods (Coley & Medeiros, 2007). It is important to note that the present sample was based on public court records with a divorce decree from a county sampling frame including rural and urban areas. There are known limitations to court records based studies involving participation of families who separate and do not file for divorce and inferences based on families in which the marital dissolution and disruptions to social interactional may have occurred long before filing. Related, the present study was limited because it was not a prospective study of divorce and did not have measures of children’s pre-divorce functioning, parenting, or estimates of mothers’ parenting; all of which factors are likely to influence children’s problem behaviors and growth. Given these limitations, a strength of the present study involved use of father-child and father-confidant observations that replicated and extended prior divorced mother studies using a longitudinal evaluation.

Appendix.

Bivariate Correlation Matrix for All Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | .11 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | .03 | −.50 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | .02 | −.10 | −.03 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | −.04 | −.19 | .13 | .09 | |||||||||||||||||

| 6 | .09 | −.05 | −.07 | −.06 | .33 | ||||||||||||||||

| 7 | .04 | .03 | −.09 | −.07 | .35 | .82 | |||||||||||||||

| 8 | .09 | .01 | −.04 | .00 | .31 | .34 | .30 | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | .09 | −.14 | .11 | .09 | .27 | .41 | .53 | .50 | |||||||||||||

| 10 | .05 | .02 | .02 | .08 | −.17 | −.25 | −.31 | −.14 | −.10 | ||||||||||||

| 11 | .03 | .01 | .04 | .17 | .00 | −.10 | −.18 | −.05 | −.24 | .43 | |||||||||||

| 12 | −.24 | −.04 | −.09 | −.15 | .11 | .19 | .28 | .23 | .13 | −.49 | −.22 | ||||||||||

| 13 | −.36 | −.09 | .01 | −.16 | −.08 | .10 | .13 | .09 | .25 | −.23 | −.59 | .36 | |||||||||

| 14 | .07 | −.06 | −.06 | −.01 | −.02 | .02 | .01 | .02 | .02 | .17 | .19 | −.12 | −.11 | ||||||||

| 15 | .01 | .04 | −.05 | .04 | .01 | −.11 | −.05 | .10 | .07 | .17 | .17 | −.10 | −.10 | .78 | |||||||

| 16 | .05 | −.05 | −.12 | .11 | −.04 | −.06 | −.05 | .08 | −.01 | .14 | .25 | −.07 | −.12 | .74 | .78 | ||||||

| 17 | −.15 | −.06 | .08 | .07 | .02 | −.19 | −.11 | −.10 | −.18 | .12 | .26 | −.14 | −.16 | .33 | .38 | .32 | |||||

| 18 | .12 | .00 | −.07 | −.07 | .03 | .22 | .15 | .20 | .18 | −.23 | −.33 | .19 | .21 | −.15 | −.19 | −.21 | −.49 | ||||

| 19 | −.06 | .01 | −.13 | .07 | −.04 | .04 | .10 | .08 | .03 | .07 | .08 | .01 | −.11 | .23 | .23 | .23 | .37 | −.21 | |||

| 20 | .07 | .01 | −.07 | .02 | .00 | −.07 | −.03 | −.01 | −.04 | −.00 | −.05 | −.12 | −.05 | .13 | .19 | .19 | .21 | .03 | .16 | ||

| 21 | .07 | −.11 | .11 | .06 | .03 | .09 | .04 | −.02 | −.07 | .02 | .03 | .04 | −.15 | −.04 | −.11 | −.13 | −.15 | −.01 | −.10 | −.38 | |

| 22 | .08 | .14 | −.10 | −.04 | −.08 | .00 | .02 | −.03 | −.01 | .12 | −.04 | −.18 | .01 | .09 | .11 | .15 | .04 | .05 | .33 | .42 | −.08 |

Note:

1- Child age, 2-Confidant Gender, 3-Confidant Partner, 4-Father Contact, 5-FPP Support Behaviors, 6-Support Parenting Problem, 7-Support Personal Problem, 8-Problem Solving Outcome Parenting Issue, 9-Problem Solving Outcome Personal Issue, 10-T1 Coercive Discipline, 11-T2 Coercive Discipline, 12-T1 Prosocial Parenting, 13-T2 Prosocial Parenting, 14-T1 ASEBA T, 15-T2 ASEBA T, 16-T3 ASEBA T, 17-Father MMPI Tri, 18-Father NEO Agree, 19-Father Substance Use, 20-Confidant MMPI Tri, 21-Confidant NEO Agree, 22-Confidant Substance Use

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number R01 HD 42115 funded by the Demographic and Behavioral Sciences Branch of the NICHD, and in part, by grants P30 DA 023920, Division of Epidemiology, Services and Prevention Branch, NIDA and R01 DA 16097 Prevention Research Branch, NIDA. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The final publication is available at www.springerlink.com

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Andresen PA, Telleen SL. The relationship between social support and maternal behaviors and attitudes: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1992;20(6):751–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baucom BR, McFarland PT, Christensen A. Gender, Topic, and Time in Observed Demand–Withdraw Interaction in Cross- and Same-Sex Couples. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24(3):233–242. doi: 10.1037/a0019717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesanz JC, Deeb-Sossa N, Papadakis AA, Bollen KA, Curran PJ. The role of coding time in estimating and interpreting growth curve models. Psychological Methods. 2004;9(1):30–52. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braver SL, Bay RC. Assessing and compensating for self-selection bias (Non-representativeness) of the family research sample. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1992;54:925–939. [Google Scholar]

- Braver SL, Griffin WA, Cookston JT. Prevention programs for divorced nonresident fathers. Family Court Review. 2005;43(1):81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Braver SL, Shapiro JR, Goodman MR. Consequences of divorce for parents. In: Fine MA, Harvey JH, editors. Handbook of Divorce and Relationship Dissolution. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006. pp. 313–337. [Google Scholar]

- Brotherson SE, Dollahite DC, Hawkins AJ. Generative fathering and the dynamics of connection between fathers and their children. Fathering. 2005;3(1):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Brown HC, Wang W, Kellam SG, Muthén BO, Petras H, Toyinbo P, et al. Methods for testing theory and evaluating impact in randomized field trials: Intent-to-treat analyses for integrating the perspectives of person, place, and time. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95(Suppl1):S74–S104. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleson BR. Comforting as social support: Relational consequences of supportive behaviors. In: Duck SW, Silver RC, editors. Personal relationships as social support. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. pp. 66–82. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo JT. The relationship between non-resident fathers’ social networks and social capital and the establishment of child support orders. Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31:533–540. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo JT, Fenzl-Crossman A. The relationship between non-marital fathers’ social networks and social capital and father involvement. Child & Family Social Work. 2010;15(1):66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballo R, McLoyd VC. Social support and parenting in poor, dangerous neighborhoods. Child Development. 2002;73(4):1310–1321. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley RL, Hernandez DC. Predictors of paternal involvement for resident and nonresident low-income fathers. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(6):1041–1056. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley RL, Medeiros BL. Reciprocal longitudinal relations between nonresident father involvement and adolescent delinquency. Child Development. 2007;78(1):132–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Domains and facets: Hierarchical personality assessment using the revised NEO personality inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1995;64:21–50. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6401_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cowan CP, Pruett MK, Pruett K, Wong JJ. Promoting fathers’ engagement with children: Preventive interventions for low-income families. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2009;71:663–679. [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS. Coercive and prosocial fathering, antisocial personality, and growth in children’s postdivorce noncompliance. Child Development. 2010;81(2):503–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Forgatch MS. Determinants of observed confidant support for divorced mothers. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1997;72(2):336–345. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Forgatch MS. Efficacy of parent training for stepfathers: From playful spectator and polite stranger to effective stepfathering. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2007;7(4):1–25. doi: 10.1080/15295190701665631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Patras J, Eap S. Social Support for divorced fathers’ parenting: Testing a stress buffering model. Family Relations. 2008;57:35–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMaris A, Greif GL. Single custodial fathers and their children: When things go well. In: Hawkins AJ, Dollahite DC, editors. Generative fathering: Beyond deficit perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. pp. 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K. Intervening in adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Owen LD, Bullock BM. Like father, like son: Toward a developmental model for the transmission of male deviance across generations. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2004;1(2):105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J, Bernd E, Whiteman V. Adolescent Fathers’ Parenting Stress, Social Support, and Involvement with Infants. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS. Patterns and outcome in family problem solving: The disrupting effect of negative emotion. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1989;51:115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, DeGarmo DS. Confidant contributions to parenting and child outcomes. Social Development. 1997;6(2):237–253. [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Furrer C, McAllister C. How do relationships support parenting? Effects of attachment style and social support on parenting behavior in an at-risk population. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;40:96–108. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9127-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbert JS, Acock AC. The effects of marital status on the form and composition of social networks. Social Science Quarterly. 1990;71:163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A. Life with (or without) father: The benefits of living with two biological parents depend on the father’s antisocial behavior. Child Development. 2003;74(1):109–126. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeličić H, Phelps E, Lerner RM. Use of missing data methods in longitudinal studies: The persistence of bad practices in developmental psychology. Developmental Psychobiology. 2009;45(4):1195–1199. doi: 10.1037/a0015665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D, Davies M, Baydar N. The creation of interpersonal contexts: Homophily in dyadic relationships in adolescence and young adulthood. In: Robins L, Rutter M, editors. Straight and devious pathways from childhood to adulthood. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 221–241. [Google Scholar]

- Lakey B, Lutz CJ. Social support and preventive and therapeutic interventions. In: Pierce GR, Sarason BR, Sarason IG, editors. Handbook of social support and the family. New York: Plenum Press; 1996. pp. 435–465. [Google Scholar]

- Leinonen JA, Solantaus TS, Punamäki RL. Social support and the quality of parenting under economic pressure and workload in Finland: The role of family structure and parental gender. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17(3):409–418. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Umberson DJ. The times they are a changing: Marital status and health differentials from 1972 to 2003. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2008;49:239–253. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman HJ, Silvern L, Clements M, Kraft-Hanak S. Men and women dealing with conflict in heterosexual relationships. Journal of Social Issues: Gender Differences and Emotional Expressiveness. 1993;49(3):107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castilia; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. The next generation of PMTO models. Behavior Therapist. 2005;28(2):25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Forgatch MS. Initiation and maintenance of process disrupting single-mother families. In: Patterson GR, editor. Depression and aggression in family interaction. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1990. pp. 209–245. [Google Scholar]

- Pfiffner LJ, McBurnett K, Rathouz PJ. Father absence and familial antisocial characteristics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29(5):357–367. doi: 10.1023/a:1010421301435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond C, Spoth R, Trudeau L. Family- and community-level predictors of parent support seeking. Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30(2):153–171. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Hacker TA, Basham RB. Concomitants of social support: Social skills, physical attractiveness and gender. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;49(2):469–480. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, Leppin A. Social support and health: A theoretical and empirical overview. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1991;8:99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Scott KL, Crooks CV. Effecting Change in Maltreating Fathers: Critical Principles for Intervention Planning. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11(1):95–111. [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S, Felmlee D, Schmeeckle M, Shu X, Fine MA, Harvey JH. No Breakup Occurs on an Island: Social Networks and Relationship Dissolution. In: Fine MA, Harvey JH, editors. Handbook of divorce and relationship dissolution. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 457–478. [Google Scholar]

- Stone G. Nonresidential father postdivorce well–being: The role of social supports. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage. 2002;36(3/4):139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs J, Crosby L, Forgatch MS, Capaldi DM. Family and peer process code: A synthesis of three Oregon Social Learning Center behavior codes (Training manual.) Oregon Social Learning Center; 10 Shelton McMurphey Blvd., Eugene, OR 97401: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson SC, Templer DI, Streiner DL, Reynolds RM, Miller HR. Development of a three-scale MMPI: The MMPI-TRI. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995;51(3):361–374. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199505)51:3<361::aid-jclp2270510307>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]