Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are an abundant class of small RNAs that regulate expressions of most genes. miRNAs play important roles in the pituitary, the “master” endocrine organ.However, we still don't know which role miRNAs play in the development of pituitary tissue or how much they contribute to the pituitary function. By applying a combination of microarray analysis and Solexa sequencing, we detected a total of 450 miRNAs in the porcine pituitary. Verification with RT-PCR showed a high degree of confidence for the obtained data. According to the current miRBase release17.0, the detected miRNAs included 169 known porcine miRNAs, 163 conserved miRNAs not yet identified in the pig, and 12 potentially new miRNAs not yet identified in any species, three of which were revealed using Northern blot. The pituitary might contain about 80.17% miRNA types belonging to the animal. Analysis of 10 highly expressed miRNAs with the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) indicated that the enriched miRNAs were involved not only in the development of the organ but also in a variety of inter-cell and inner cell processes or pathways that are involved in the function of the organ.

We have revealed the existence of a large number of porcine miRNAs as well as some potentially new miRNAs and established for the first time a comprehensive miRNA expression profile of the pituitary. The pituitary gland contains unexpectedly many miRNA types and miRNA actions are involved in important processes for both the development and function of the organ.

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a family of small RNAs that function as regulators of messenger RNAs [1]. Their discovery has revealed a new level of gene regulation in eukaryotes [2]. In animals, miRNAs regulate gene expression mainly by sequence-specific targeting of the 3′untranslated regions of target mRNAs, which usually results in repression of the gene expression [3]. Occasionally, miRNAs can suppress or activate genes by causing histone modification and DNA methylation of promoter sites [4], [5], or by targeting gene promoters [6]. miRNAs may target about 60% of mammalian genes [7] and have been shown to be involved in a wide range of biological processes including development, differentiation, proliferation, and immune response [8], [9], [10], [11]. Most interestingly, animal miRNAs target some developmental genes specifically [12] and many miRNAs are expressed in a temporal or tissue-specific pattern [13]. Therefore, miRNAs may be particularly involved in regulating development and function of tissues and organs.

The pig (Sus scrofa) is an important animal not only for meat production but also as a model organism for comparative studies [14]. Despite the significant role of the animal, the current miRBase release 17.0 [15] listed only 228 distinct miRNA sequences in pigs [16], [17], [18], which is substantially less compared with human and mouse miRNAs (1424 and 720 respectively). MiRNAs were first studied in pigs by Wernersson et al [19], and Sawera et al. identified the first porcine miRNA cluster [20]. At the beginning, new porcine miRNAs were found using a homology search [21]. With the emergence of microarray and Solexa sequencing, the abundance of porcine miRNA was found, most of them focused on porcine miRNAs from the skeletal muscle and adipose tissuein all life stages [18], [22], [23], [24]. One study focused on the developing brain [17], but none has focused on miRNAs from the pituitary.

The pituitary is a pea-sized gland located at the base of the brain and attached to the hypothalamus by nerve fibers. It is the “master” endocrine organ as it receives signals from the brain and uses these messages to produce hormones that affect many body processes, including animal growth, bone metabolism, and the cell generation cycle [25], [26], [27]. Profiling pituitary miRNAs may thus enable us to elucidate not only how miRNAs are involved in regulating the development and function of the organ but also how miRNAs are involved in regulating the development of the individual or species characteristics of an animal. Thus far, only a few studies have addressed the involvement of miRNAs in the functions of the pituitary; miR-26 has recently been reported to be critical for anterior pituitary development [28], and most others are related to the development of tumors. For example, miR-15 and miR-16 were found to be down-regulated in pituitary adenomas and correlated with the secretion of P43, a precursor of the inflammatory cytokine endothelial monocyte-activating polypeptide II [29]. The expression of the miR-30 family strongly increased while miR-26a and miR-212 were strongly down-regulated in the pituitary gland with ACTH-secreting adenomas [30]. miRNAs actions in the pituitary remain largely unknown.

We conducted an investigation of miRNAs in the porcine pituitary through microarray, Solexa sequencing and real-time PCR. With these powerful technologies, we have identified a large number of porcine miRNAs that are not registered in the Sus scrofa miRBase and some new potential porcine miRNAs that have not yet been identified in any species. We have obtained for the first time a comprehensive profile of miRNAs in the porcine pituitary, which provides fundamental information on the miRNAs actions in this “master” endocrine organ.

Results

miRNAs and their expressions in the porcine pituitary detected by microarray assay

We applied miRCURY™ LNA Arrays to examine the expression of miRNAs in the porcine pituitary. The chips contain probes for 2500 miRNAs identified in all species including the pig but excluding humans, rats, mice and viruses. With this microarray, we detected a total of 418 miRNAs in the porcine pituitary. According to the miRBase17.0, we have detected 154 known porcine miRNAs (Table 1) and 264 conserved porcine miRNAs by the microarray assay (Table 2). Among the detected miRNAs, 53 had an expression signal greater than 1, 26 reached a signal greater than 2, and 18 reached a signal greater than 3, each with the miR-7 on the top (16.8), which was significantly higher than the expression in skeletal muscles and adipose tissues (data unpublished). These enriched miRNAs should be the main active players of miRNA regulation in the porcine pituitary.

Table 1. Known porcine miRNAs# detected in pituitary by microarray.

| miRNA | signal | miRNA | signal | miRNA | signal | miRNA | signal |

| miR-7 | 16.7999 | miR-500 | 0.7153 | miR-181d | 0.1607 | miR-499 | 0.0394 |

| let-7a | 9.1408 | miR-149 | 0.6334 | miR-98 | 0.1460 | miR-455 | 0.0378 |

| miR-125b | 8.6723 | miR-99a | 0.5987 | miR-365 | 0.1460 | miR-542 | 0.0368 |

| let-7c | 7.8025 | miR-143 | 0.5704 | miR-15b | 0.1366 | miR-532 | 0.0368 |

| miR-125a | 7.2379 | miR-432 | 0.5625 | miR-128 | 0.1350 | miR-217 | 0.0362 |

| let-7e | 6.8955 | miR-152 | 0.5242 | miR-378 | 0.1308 | miR-652 | 0.0357 |

| miR-26a | 5.3472 | miR-23b | 0.5158 | miR-324 | 0.1297 | miR-92a | 0.0347 |

| miR-29a | 4.5877 | miR-429 | 0.5116 | miR-204 | 0.1292 | miR-155 | 0.0320 |

| miR-30a | 4.1003 | miR-184 | 0.5084 | miR-146b | 0.1261 | miR-122 | 0.0310 |

| miR-22 | 3.1544 | miR-423 | 0.4932 | miR-708 | 0.1218 | miR-342 | 0.0268 |

| let-7i | 3.1497 | miR-101b | 0.4932 | miR-1306 | 0.1203 | miR-376a | 0.0263 |

| miR-30b | 2.8398 | miR-15a | 0.4874 | miR-338 | 0.1171 | miR-195 | 0.0252 |

| miR-135a | 2.4706 | miR-221 | 0.4706 | miR-133b | 0.1145 | miR-505 | 0.0236 |

| miR-491 | 2.1712 | miR-758 | 0.4690 | miR-193a | 0.1124 | miR-18a | 0.0236 |

| let-7g | 2.1460 | miR-28 | 0.4585 | miR-140 | 0.1019 | miR-34c | 0.0215 |

| miR-191 | 2.0021 | miR-362 | 0.4554 | miR-95 | 0.1003 | miR-328 | 0.0184 |

| miR-30c | 1.9685 | miR-503 | 0.4501 | miR-424 | 0.0977 | miR-27a | 0.0168 |

| miR-136 | 1.6886 | miR-339 | 0.4443 | miR-10b | 0.0961 | miR-490 | 0.0163 |

| miR-335 | 1.5935 | miR-299 | 0.3803 | miR-615 | 0.0956 | miR-1307 | 0.0126 |

| miR-222 | 1.5011 | miR-185 | 0.3640 | miR-363 | 0.0956 | miR-381 | 0.0110 |

| miR-101a | 1.4816 | miR-99b | 0.3424 | miR-484 | 0.0903 | miR-18b | 0.0110 |

| miR-30d | 1.4359 | miR-382 | 0.3062 | miR-20 | 0.0872 | miR-301c | 0.0100 |

| miR-127 | 1.4359 | miR-340 | 0.3041 | miR-885 | 0.0867 | miR-107 | 0.0095 |

| miR-19b | 1.4296 | miR-411 | 0.2983 | miR-628 | 0.0840 | miR-301b | 0.0084 |

| miR-30e | 1.4265 | miR-130a | 0.2946 | miR-19a | 0.0783 | miR-451 | 0.0079 |

| miR-23a | 1.3829 | miR-10a | 0.2873 | miR-17 | 0.0772 | miR-190 | 0.0079 |

| miR-100 | 1.3025 | miR-369 | 0.2742 | miR-181c | 0.0767 | miR-219 | 0.0063 |

| miR-29b | 1.1849 | miR-374b | 0.2731 | miR-130b | 0.0709 | miR-146a | 0.0063 |

| miR-24 | 1.1239 | miR-425 | 0.2642 | miR-106a | 0.0678 | miR-504 | 0.0058 |

| miR-151 | 1.1113 | miR-133a | 0.2631 | miR-1 | 0.0662 | miR-1271 | 0.0053 |

| miR-361 | 1.0336 | miR-664 | 0.2384 | miR-16 | 0.0625 | miR-183 | 0.0047 |

| miR-376c | 1.0152 | miR-450a | 0.2384 | miR-486 | 0.0614 | let-7f | 0.0032 |

| miR-320 | 0.8824 | miR-487b | 0.2353 | miR-214 | 0.0572 | miR-32 | 0.0026 |

| miR-331 | 0.8314 | miR-92b | 0.2048 | miR-202 | 0.0557 | miR-301a | 0.0026 |

| miR-186 | 0.8078 | miR-145 | 0.1943 | miR-199b | 0.0541 | miR-574 | 0.0021 |

| miR-181a | 0.7868 | miR-142b | 0.1901 | miR-383 | 0.0520 | miR-124a | 0.0011 |

| miR-21 | 0.7857 | miR-376b | 0.1770 | miR-9 | 0.0515 | miR-1224 | 0.0011 |

| miR-148b | 0.7847 | miR-181b | 0.1723 | miR-421 | 0.0499 | ||

| miR-494 | 0.7600 | miR-148a | 0.1612 | miR-323 | 0.0431 |

Note: # porcine miRNAs deposited in miRBase release 17.0.

Table 2. Conserved porcine miRNAs# newly detected in porcine pituitary by microarray.

| miRNA | signal | miRNA | signal | miRNA | signal | miRNA | signal |

| miR-997 | 0.0504 | miR-642 | 0.1056 | miR-296-5p | 0.1465 | miR-1494 | 0.0152 |

| miR-993 | 0.0005 | miR-638 | 0.0121 | miR-296-3p | 0.2337 | miR-1493 | 0.0657 |

| miR-989 | 0.1660 | miR-63 | 0.0515 | miR-285 | 0.0357 | miR-142a-5p | 0.1922 |

| miR-987 | 0.0047 | miR-625 | 0.0053 | miR-282 | 0.0930 | miR-133d | 0.0032 |

| miR-974 | 0.1481 | miR-611 | 0.0184 | miR-269 | 0.0625 | miR-129 | 2.5861 |

| miR-965 | 0.1161 | miR-605 | 0.0625 | miR-268 | 0.0011 | miR-126 | 0.6933 |

| miR-964 | 0.2143 | miR-589 | 0.0021 | miR-265 | 0.0074 | miR-1239 | 0.4569 |

| miR-962 | 0.0016 | miR-587 | 0.0074 | miR-263 | 0.0793 | miR-1235 | 0.0242 |

| miR-940 | 0.1050 | miR-582 | 0.0404 | miR-256 | 0.0457 | miR-1232 | 0.1964 |

| miR-939 | 0.4013 | miR-56 | 0.2279 | miR-255 | 0.1371 | miR-1230 | 0.2532 |

| miR-936 | 1.0509 | miR-557 | 0.1597 | miR-253 | 0.0546 | miR-1225-3p | 0.0110 |

| miR-933 | 3.3461 | miR-552 | 0.0200 | miR-24b | 0.0888 | miR-1175 | 0.1801 |

| miR-922 | 0.3104 | miR-550 | 1.6166 | miR-247 | 0.0100 | miR-1174 | 0.0788 |

| miR-901 | 1.3209 | miR-55 | 0.5021 | miR-246 | 0.0011 | miR-1144a | 0.0783 |

| miR-90 | 0.1660 | miR-548b | 0.0032 | miR-245 | 0.1318 | miR-1066 | 0.1329 |

| miR-889 | 0.0310 | miR-542-5p | 0.0221 | miR-243 | 0.0704 | miR-105b | 0.0368 |

| miR-887 | 0.4632 | miR-525 | 0.0704 | miR-241 | 0.0551 | miR-83 | 0.0425 |

| miR-877 | 0.0226 | miR-52 | 0.1518 | miR-237 | 0.0289 | miR-767 | 0.0315 |

| miR-875 | 0.0762 | miR-519a | 0.0068 | miR-235 | 0.1045 | miR-649 | 0.0714 |

| miR-863-3p | 0.0383 | miR-518b | 0.1176 | miR-231 | 0.0011 | miR-616 | 0.2416 |

| miR-82 | 0.1292 | miR-518a | 0.0667 | miR-230 | 0.3062 | miR-523 | 0.0021 |

| miR-81 | 0.0935 | miR-513c | 0.1124 | miR-223 | 0.0599 | miR-519d | 0.0095 |

| miR-80 | 0.0116 | miR-513b | 0.0362 | miR-220d | 0.0005 | miR-38 | 0.0961 |

| miR-8 | 0.4632 | miR-513b | 0.0236 | miR-220b | 0.0525 | miR-34b | 0.0720 |

| miR-7c | 2.1050 | miR-513a | 0.1434 | miR-220a | 0.0688 | miR-2a | 0.1213 |

| miR-799 | 0.0152 | miR-508 | 0.0436 | miR-205b | 0.3030 | miR-260 | 0.0053 |

| miR-795 | 0.3803 | miR-502a | 0.0352 | miR-199a | 0.2353 | miR-240 | 0.1197 |

| miR-789b | 0.0184 | miR-501 | 0.0026 | miR-199 | 0.1738 | miR-218a | 0.1003 |

| miR-786 | 0.0074 | miR-498 | 0.1786 | miR-198 | 0.0184 | miR-1b | 0.0478 |

| miR-765 | 0.0184 | miR-489 | 0.0142 | miR-1841 | 0.0053 | miR-1844 | 0.2495 |

| miR-757 | 0.0037 | miR-466 | 0.1854 | miR-1832 | 0.3230 | miR-166c | 0.1071 |

| miR-748 | 0.2521 | miR-412 | 0.0042 | miR-1824 | 0.1670 | miR-1496 | 0.2883 |

| miR-738 | 0.0604 | miR-41 | 0.0011 | miR-1822 | 0.0089 | miR-1240 | 0.0042 |

| miR-735 | 0.0042 | miR-399f | 1.0551 | miR-17-3p | 0.0247 | miR-1036 | 0.1203 |

| miR-731 | 0.0032 | miR-399a | 0.0373 | miR-166a | 0.0557 | miR-103 | 0.8214 |

| miR-73 | 0.0194 | miR-395c | 1.0425 | miR-1545 | 0.0110 | miR-1023a-5p | 0.1014 |

| miR-727 | 0.0037 | miR-375 | 2.2085 | miR-153b | 0.0011 | miR-1022 | 0.1775 |

| miR-71c | 0.0053 | miR-374a | 0.8971 | miR-1506 | 0.0047 | miR-1013 | 0.0362 |

| miR-675 | 0.1549 | miR-33 | 0.0016 | miR-1497h | 0.1597 | miR-1012 | 0.0956 |

| miR-67-3p | 0.0121 | miR-31b | 0.0074 | miR-1497f | 0.3839 | miR-101 | 1.0000 |

| miR-668 | 0.0341 | miR-29d | 0.0593 | miR-1497e | 0.0011 |

Note: # porcine miRNAs not yet deposited in miRBase release 17.0;

miRNAs identified in the porcine pituitary via Solexa sequencing

Considering that the miRNAs known in the pig are far fewer than those known in human or mice, and our microarray chips contained only 120 porcine probes, we conducted Solexa sequencing to discover some miRNAs that our microarray might fail to detect and obtain the porcine miRNA sequences that are not yet available. A total of 11,209,341 clean reads were sequenced from the pituitary tissue (Figure S1). These reads contained 744,371 unique sequences, and 109,524 of them can be mapped to the genome (Illumina Genome Analyzer System). After eliminating the unknown and repeat sequences as well as other small RNA reads such as tRNA, rRNA, snoRNA, and piRNA, the remaining 8507 mapped sequences were “blasted” to the miRBase (release17.0) and the matched sequences were annotated according to their similarities with known mature miRNA sequences deposited in the miRBase. As a result, 1312 unique sequences representing 105 mature miRNAs were identified (Table S1), each miRNA include multiple mature variants (Table S2), called isomiRs as other literatures reported [16], [24]. Most of these miRNAs were 18–25 nt long with the peak at 22 nt in the length distribution curve (Fig. 1). Among these cloned and sequenced porcine miRNAs, there were 20 miRNAs that had not been detected by the microarray analysis (Table 3). These miRNAs were either not included in the available commercial microarray chips (underlined in the Table 3), or had a low expression as determined by their low sequencing frequency (lower than 125) except miR-139 (378) and miR-210 (346). Eight miRNAs have not yet been deposited in the Sus scrofa miRNA database, but their sequences displayed a perfect or nearly perfect match (mismatch≤1) to orthologous miRNAs of other organisms. They were thus porcine conserved miRNAs. Six of them were identified by Li et al. [24], two (miR-2366 and miR-3613) were identified by us for the first time (Table 4). Of them, six have been also obtained from the skeletal muscle and adipose tissues in our previous work (data not published), and the other two miRNAs (underlined in the Table 4) were detected only in the pituitary but not in the skeletal muscle and adipose tissues.

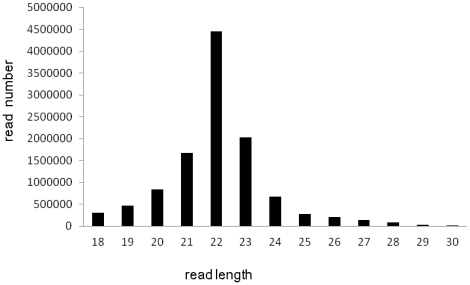

Figure 1. The size distribution of miRNA reads sequenced by solexa.

A total of 11,209,341 reads ranging from 18 to 30 base pair [46] in length. The length distribution peaked at 22 bp, which is consisted with commonly expected for miRNAs' length.)

Table 3. Conserved porcine miRNAs identified in pituitary by Solexa sequencing but not by microarray analysis.

| Name | Count | Name | Count | Name | Count | Name | Count |

| miR-744 | 2821 | miR-2483 | 143 | miR-450c | 28 | miR-1296 | 10 |

| miR-139 | 978 | miR-325 | 96 | miR-215 | 27 | miR-190a* | 6 |

| miR-210 | 346 | miR-2366# | 274 | miR-224 | 21 | miR-326 | 4 |

| miR-1277 | 214 | miR-206 | 83 | miR-217 | 13 | miR-216 | 1 |

| miR-1839# | 123 | miR-760 # | 55 | miR-205 | 12 | miR-3613# | 12 |

Notes: porcine miRNA not yet deposited in miRBase release 17.0;

*miRNA processed from the hairpin arm opposite of the mature miRNA; the underline indicates no probes included in the microarray chips.

Table 4. Conserved porcine miRNAs# newly identified in pituitary by Solexa sequencing.

| Name | Count | Sequence(5′–3′) | Size | Conservation | Match |

| miR-31 | 20578 | AGGCAAGATGCTGGCATAGCTGT | 23 | cfa | perfect |

| miR-137 | 2053 | TTATTGCTTAAGAATACGCGTA | 22 | hsa,mmu,rno,dre,fru,mml,oan,prt,bta,eca,tgu,ppy,gga,xtr,mdo,cfa | perfect |

| miR-660 | 1961 | TACCCATTGCATATCGGAGTTG | 22 | cfa,mml,hsa,ptr,eca | perfect |

| miR-1468 | 317 | CTCCGTTTGCCTGTTTTGCTGA | 22 | bta | perfect |

| miR-2366 | 274 | TGGGTCACAGAAGAGGGTCTGG | 22 | bta | perfect |

| miR-2483 | 143 | AACATCTGGTTGGTTGAGAGA | 21 | bta | 1 nt insersionless |

| miR-760 | 55 | CGGCTCTGGGTCTGTGGGGAG | 20 | hsa,mmu,rno,ptr,mml, ppy | perfect |

| miR-3613-5P | 12 | TGTTGTACTTTTTTTTTTGTT | 21 | hsa | perfect |

bta, Bos taurus; cfa, Canis familiaris; dre, Danio rerio; eca,Equus caballus; fru, Fugu rubripes; gga, Gallus gallus;hsa, Homo sapiens; mdo, Monodelphis domestica; mml, Macaca mulatta; mmu, Mus musculus; oan, Ornithorhynchus anatinus; ppy, Pongo pygmaeus; ptr,Pan troglodytes; rno, Rattus norvegicus; tgu,Taeniopygia guttata; xtr, Xenopus tropicalis.

Note: # Porcine miRNAs not yet deposited in miRBase release 17.0; the underlined miRNAs were detected only in the porcine pituitary but not in the skeletal muscle and in adipose tissues.

The ability of the pre-miRNA sequence to form a canonical stem-loop hairpin structure is one of the critical features that distinguish miRNAs from other small endogenous RNAs [31], [32]. We thus used the remaining 7227 sequences that were mapped to the pig genome but did not match any sequences in miRBase 17.0 to search for potentially new miRNAs by structural reconstruction with their flanking sequence. As a result, 12 potentially new porcine miRNAs were identified by the Mfold and MiReap programs; the precursors can form secondary structures containing stable stem-loops with a minimum free energy less than −20 kcal/mol (Table S3). Among them, ssc-miR-new5 and ssc-miR-new10 has the same seed sequences with miR-2287 and miR-3275, respectively. Other miRNAs represent either porcine-specific or conserved miRNAs not yet discovered in other organisms.

Validation of miRNA expression via stem-loop real-time PCR

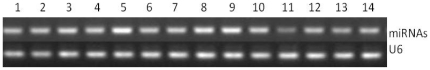

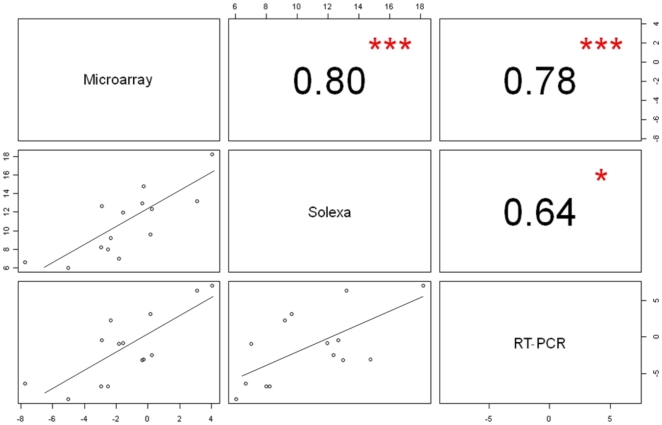

To verify and evaluate the reliability of the results from the two platforms, we selected 14 miRNAs for stem-loop real-time PCR assay. These miRNAs were selected from the 81 miRNAs that could be detected by both microarray analysis and Solexa sequencing at different levels of expression. The selection included miR-7, which was ranked at the top for its expression by both methods and miRNAs that had a microarray fold change as low as 0.0047 and a Solexa sequencing frequency count as low as 168. All the miRNAs were successfully detected by the real-time PCR, suggesting that the miRNAs identified by our microarray analysis and Solexa sequencing were reliable for their existence. However, the expression levels detected with the 3 platforms differ to some extent for certain miRNAs. As shown in Figure 2, the expression levels determined by microarray analysis were quite consistent with those determined by real-time PCR assay and Solexa sequencing with Pearson correlation coefficients (R) of 0.80 and 0.78, respectively; whereas the levels determined by Solexa sequencing were a little inconsistent with those determined by real-time PCR (R = 0.64)(Figure 3). This suggested that Solexa sequencing is a more advanced technique for discovering novel miRNAs, but it is somewhat inferior to the microarray method in miRNA quantification.

Figure 2. RT-PCR verification of miRNAs detected by microarray and solexa sequencing.

The selected miRNAs for the analysis include: miR-99b, miR-204, miR-27a, miR-24, miR-7, miR-145, miR-124, miR-21, miR-125b, miR-30b, miR-128a, miR-122, miR-183, and miR-103.

Figure 3. Correlation coefficient matrix for microarray analysis, Solexa sequencing, and RT-PCR.

The selected miRNAs for the analysis include: miR-99b, miR-204, miR-27a, miR-24, miR-7, miR-145, miR-124, miR-21, miR-125b, miR-30b, miR-128a, miR-122, miR-183, and miR-103.

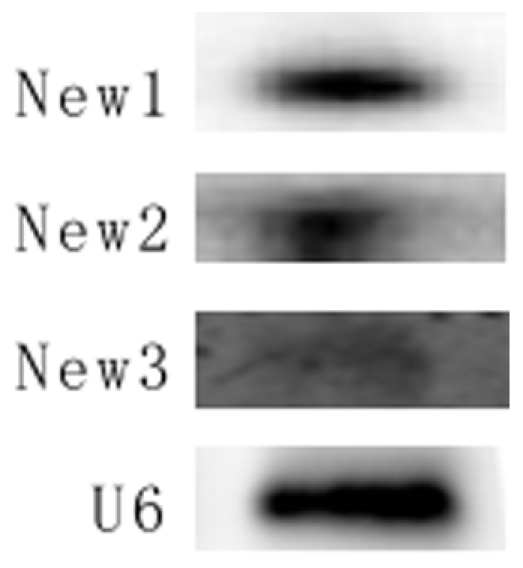

Validation of new miRNAs using Northern blot

The top three highly expressed new miRNAs were confirmed by Northern blot, all of them have been detected in the pituitary tissue (Figure 4).

Figure 4. New potential miRNAs in pig pituitary revealed via northern blot.

Three new potential miRNAs in pig pituitary were successfully revealed using northern blot, U6 was control. New1, new2 and new3 were listed in Table S3.

miRNA target predictions and KEGG pathway analysis

To gain insight into the general functions of miRNAs in the pituitary, the 10 most abundant miRNAs, except for the let-7 family that is well known to be ubiquitously expressed, were selected for predicting target genes and classified according to KEGG functional annotation using DAVID bioinformatics resources [33]. A total of 2099 target genes were predicted and 12 possible pathways were revealed (Table 5). It appeared that the enriched miRNAs in the pituitary were intensively involved in not only the development of the nervous system such as axonal guidance neurotrophin-signaling, but also the function of the organ such as long-term potentiation and sodium reabsorption. Their roles involved regulations of important inner cell processes such as actin-cytoskeleton regulation, ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, and regulation of important signaling pathways including MAPK and mTOR pathways and pathways in cancer, as well as regulations of intercellular activities such as focal adhesion.

Table 5. Pathways probably regulated by top10 enriched miRNAs in porcine pituitary.

| Term | Count | P Value | Benjamini |

| hsa04360: Axon guidance | 42 | 1.59E-09 | 2.53E-07 |

| hsa04510: Focal adhesion | 53 | 3.19E-08 | 2.54E-06 |

| hsa04720: Long-term potentiation | 26 | 1.12E-07 | 5.96E-06 |

| hsa05200: Pathways in cancer | 71 | 5.67E-07 | 2.25E-05 |

| hsa04722: Neurotrophin-signaling pathway | 35 | 2.04E-06 | 6.50E-05 |

| hsa05211: Renal cell carcinoma | 23 | 1.29E-05 | 3.42E-04 |

| hsa05214: Glioma | 21 | 2.71E-05 | 6.16E-04 |

| hsa04010: MAPK-signaling pathway | 56 | 2.99E-05 | 5.95E-04 |

| hsa04960: Aldosterone-regulated sodium reabsorption | 16 | 4.34E-05 | 7.66E-04 |

| hsa04810: Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | 47 | 5.19E-05 | 8.25E-04 |

| hsa04120: Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis | 34 | 5.52E-05 | 7.98E-04 |

| hsa04150: mTOR-signaling pathway | 18 | 7.15E-05 | 9.47E-04 |

Note: Probabilities were evaluated by Bonferroni correction and values less than 1E-03 were considered significant. Count represents targeted genes involved in the term.

Discussion

In this study, we applied microarray analysis and Solexa sequencing to identify the miRNA expression in the porcine pituitary, and the stem-loop real time RT-PCR to verify and evaluate the data sets obtained via the two high-throughput platforms. We found that the Solexa sequencing could be used to identify novel miRNAs with high accuracy and efficiency. However, microarray analysis appeared to surpass the “next-generation” sequencing methods in quantification. This is also the point of view of Chen et al. and Willenbrock et al. [34], [35]. This limitation of the deep-sequencing approach might be because of the cloning bias or sequencing bias that intrinsically exists in the approach. In addition, multiplexed high-throughput expression sequencing may have affected data quality [35], and fragments with the same seed sequence were regarded as the same miRNA. Further, physical properties or post-transcriptional modifications may make some miRNAs difficult for sequencing. All these factors may decrease the accuracy of the quantification.

By applying two powerful and related technologies, we have obtained a rather comprehensive expression profile of miRNAs in porcine pituitary. The profile included 450 miRNAs, of which 169 were known porcine miRNAs, 269 were conserved miRNAs that can't find in the miRBase porcine data and 12 potentially new miRNAs that have not yet been identified in any species. Of the conserved miRNAs, 106 have been reported in other research [16], [17], [18], [22], [24], and 163 were not yet identified in the pig.

From the known porcine miRNA data, it can be estimated that the porcine pituitary contains at least 74% (169/228) of all miRNA types found in the animal. Although most of them have very low expressions, we have detected 18 miRNAs with more than 3-fold enrichment (signal>3) in the porcine pituitary. Bak et al. reported 8 miRNAs (mir-7, mir-7b, mir-375, mir-141 , mir-200a, mir-200c, mir-25and mir-152) with more than 3-fold enrichment in the pituitary of adult mice in a profile of the miRNAs in the central nervous system [36]; and Farh et al. and Landgraf et al. reported 6 (mir-7, mir-212, mir-26a, mir-191, mir-375 and mir-29) when comparing the miRNAs in normal and tumor pituitary cells [37], [38]. Although those reported data were quite incomplete for miRNA profiles in pituitary; it appeared that miR-7 is the most highly expressed miRNA in the pituitary in all the three species. The up-regulation of miR-141, miR-200a, miR-200c, miR-26a, and miR-29 we detected were also accordant either with mice or with humans. However, there equally were miRNAs that showed discordant in different organisms. For example, miR-375, which was enriched 3-fold in mouse and human pituitary, showed only 2.2-fold in the porcine pituitary; and miR-212 had threefold expression in humans but not in pigs or in mice; miR-25, in mice but not in humans or pigs. These findings indicated that different species could have varying miRNA expressions within the same tissue and/or organ. One should thus be careful in implicating miRNA information from one animal to another. It is certainly one of the most attractive and challenging questions that whether and how such conservation and variation of miRNA expressions are linked to the conserved but varying functions of the pituitaries in different animals or individuals with characterized physiologies.

Compared with skeletal muscles and adipose tissue from the same slaughtered animal (data not published), 19 miRNAs were only detected in the pituitary, suggesting these miRNAs may play important roles in pituitary-specific functions. The most up-regulated miRNA that was expressed in the pituitary relative to skeletal muscle was miR-222, and miR-1 was the most down-regulated. miR-135 was most differently expressed between the pituitary and adipose tissue, as much as 373 folds higher in pituitary, while miR-20a was the most down-regulated one that expressed in the pituitary relative to adipose tissue.

With the Solexa sequencing, four miRNAs, miR-760, miR-1296, miR-137, and miR-362, have been detected only in the pituitary but not muscle or adipose tissue. These four miRNAs also have not been deposited in the Sus scrofa database; they were first reported by Li et al. using tissues from the whole body [24]. In humans or mice, these miRNAs have been mostly associated with cancer. miR-760 is regulated by the hormone 17-beta-estradiol along with other miRNAs that can target estrogen-responsive transcripts, which is associated with the luminal-like breast tumor [39]. miR-1296 can down-regulate genes of the minichromosome maintenance (MCM) gene family, which are frequently up-regulated in various cancers [40]. miR-137 induces differentiation of adult mouse neural stem cells and stem cells derived from human glioblastoma multiform; it also regulates neuronal maturation by targeting ubiquitin ligase mind bomb-1 protein [41], [42]. The down-regulation of the miR-362 expression may obstruct the development of cultured embryos [43]. Future detail studies are required to reveal the regulation and functions of these pituitary-specific miRNAs. Furthermore, we have identified 12 new potential porcine miRNAs by Solexa sequencing and computational predictions; these miRNAs have not been found in any other species thus far. Further studies of these miRNAs could bring about new insight on miRNA actions.

Finally, the pathway analysis of the top 10 enriched miRNAs has highlighted 12 processes or pathways that the enriched miRNAs may target. These processes or pathways are crucial not only for the development of the nervous system but also for survival, growth, proliferation and motility of the cell, as well as for the development of certain tumors. All these are possible directions for future research on the roles of miRNA regulation in the pituitary.

Conclusions

We have revealed the existence of 269 porcine conserved miRNAs in addition to those deposited in the current miRBase, of which 154 by array and 2 by Solexa have been newly identified, and we have identified 12 other potentially new porcine miRNAs with their pre-mRNA predicted, which provides important complementary information to the current miRNA database. With the verification and evaluation of the data, we have established for the first time a comprehensive miRNA expression profile of the pituitary gland, which provides fundamental information on miRNA regulation and functions in the porcine pituitary. We found that the pituitary contained particularly many miRNA types relative to its small size and limited cell types in the animal; and miRNAs were dramatically regulated in the pituitary, which showed both accordant and discordant in different species. Actions involving miRNAs in the pituitary are important not only for the development but also for the function of this master endocrine organ, which could contribute to the establishment of individual and species characteristics.

Methods

Tissue collection and RNA extraction

Eight 180-day-old Lantang pigs (local strain in China) were slaughtered in a legal slaughterhouse, and the pituitary tissues were collected within half an hour and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen to ensure RNA quality. Before homogenization, pituitary tissue samples from eight animals were pooled, and total RNA was isolated from the pooled samples by using the Trizol (Invitrogen, USA) reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol. The quality of RNA was examined by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and with BioPhotometer 6131 (Eppendorf, Germany).

Ethics Statement

All of the animal slaughter experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of Guangdong Province on the Review of Welfare and Ethics of Laboratory Animals approved by the Guangdong Province Administration Office of Laboratory Animals (GPAOLA). All animal procedures were conducted under the protolcol (SCAU-AEC-2010-0416) approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of South China Agricultural University.

Computational analyses of Solexa sequencing data

All unique reads (744,371 unique in total 11,209,341 sequenced reads were sequenced in our library) were perfect mapped to pig genome using bowtie. The assembed of the pig genome (susScr2, SGSC Sscrofa9.2) were download from UCSC (http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath). Total 7,232,270 (unique 290,998 reads ) can map to genome(5,192,324 reads as 220,778 unique reads mapped to genome uniquely). All reads were align to known miRNA sequences which were download from miRBase (Release16) (http://microrna.sanger.ac.uk/sequences/), ncRNA database which was downloaded from the Rfam database (Release 10.0, http://rfam.janelia.org/), piRNA sequences which were download from RNAdb (http://jsm-research.imb.uq.edu.au/rnadb/default.aspx) respectively. Considering some reads could be mapped to multiple kinds of RNA, the reads can mapped to one kind were removed the dataset which were use to mapped to other sequences.

Map were all allow 0 mismatch, using bowtie with the following Parameter: bowtie -f –v0. Sequences that did not overlap any of these annotations were classified as “unknow”. These “unknow” sequences which mapped at most 5 times to genome were further considered as novel miRNAs candidates. To identify potential miRNA genes, the MIREAP algorithm (http://sourceforge.net/projects/mireap) was employed to obtain all candidate precursors with hairpin-like structures that would perfectly match the sequencing tags [44].

Microarray assay with miRNA chips

miRCURY™ LNA Array was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Exiqon, Denmark). Briefly, after determining the RNA concentration on a NanoDrop instrument, 10 µg of total RNA from the pooled sample was labeled by using the miRCURY™ Hy3™/Hy5™ Power labeling kit and hybridized on the miRCURY™ LNA Array (v.14.0). The array was scanned using the Axon GenePix 4000B microarray scanner. GenePix pro Version 6.0 (Axon Instruments) was used to read the raw intensity of the image. All data used for analysis had a signal-to-noise ratio of >5 and an average sum intensity of 50% higher than that of the background. Expression data were normalized using the lowess (Locally Weighted Scatter plot Smoothing) regression algorithm (MIDAS, TIGR Microarray Data Analysis System), which can produce within-slide normalization to minimize the intensity-dependent differences between the dyes. After normalization, replicated miRNAs were averaged. Differentially expressed miRNAs were identified through Fold Change filtering. Hierarchical clustering was performed using MEV software (v4.6, TIGR).

Real-time quantification of miRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR

Six pituitaries were collected from slauthereed Lantang pigs, and total RNA were seperated as discribed above. Stem-loop RT-PCR was performed as previously described [8]. In brief, 1 µg of total RNA from each sample was reverse-transcribed into cDNA by the M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Guanzhou, China) with looped antisense primers. After 1 hour of incubation at 42°C and 10 min of deactivation at 75°C, the reaction mixes was used as the templates for PCR. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed with standard protocols on a STRATAGENE Mx3005P sequence detection system. The PCR mixture contained 1 µl of cDNA (1∶10 dilution of a RT-reaction mix), 10 µl of 2× SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, 1.5 µM of each primer, and water to make up the final volume to 20 µl. The reaction was performed in a 96-well optical plate at 95°C for 1 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 56°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 40 s. All reactions were run in duplicates, and a negative control without template was included for each gene. The cycle threshold (Ct) was recorded for each reaction and the amount of each miRNA relative to that of U6 RNA was described using the expression 2−(CtmiRNA−CtU6RNA). Primers were designed on the basis of the sequenced miRNA by using Premier 5.0. (Table S4 for primer sequences).

Northern blot

RNA was extracted from the pituitary tissue of Lantang pig using the same method above. Total RNA was separated on a denaturing 15% polyacrylamideurea gels using TBE buffer, then electroblotted onto the positively charged nylon membrane (Hybond N+ nylon filter, Amersham). After transfer finished, RNA was crosslinked with ultraviolet light (Stratagene). The probes targeting ssc-new-1, ssc-new-2, ssc-new-3 miRNA were labelled with biotin and hybridized to the filter using the MiRNA Northern Blot Assay Kit according to the manufacturer's introduction (Signosis).

miRNA target predictions and KEGG pathway analysis

miRGen 2.0 database was used to predict the miRNA targets [45]. The predictions were based on human genes as Sus scrofa genes are not included in the current versions of miRGen. This approach assumes that the sequences of the miRNA target sites are conserved between orthologues.

The functional annotation of target human genes in the KEGG pathway was performd using DAVID bioinformatics resources [33]. Probabilities were evaluated by Bonferroni correction and values less than 0.001 were considered significant. The relationships between human and pig genes were based on Ensembl release 58 (http://www.ensembl.org/) and retrieved using BioMart (http://www.biomart.org/). We used orthologs between human and pig (S. scrofa) to select the pig miRNA target genes.

Statistics

Pearson's correlation coefficient R was used to measure the product-moment coefficient of correlation between the quantitative variables. All data were normalized by the Log2 (data) transformation. A scatter plot for each paired data sets was then used to analyze the linearity. The Pearson's correlation coefficient R may have any value from 0 to 1. All statistical analyses were performed with the R.

Supporting Information

Reads distribution of sRNAs sequenced by solexa.

(TIF)

Known miRNAs identified in porcine pituitary via Solexa sequencing.

(DOC)

IsomiR of porcine pituitary.

(XLS)

Potential new miRNAs# discovered in porcine pituitary.

(DOC)

Primers used in real-time PCR.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Professor Shouquan Zhang and Banling swine breeding farm in Guangdong Province for providing collection of tissue samples.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the Chinese Key Basic Plan (No. 2009CB941601), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31072105), the national Key project 2009ZX0890-024B, the Joint Funds of National Natural Science Foundation of China, u0731004. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ambros V. microRNAs: tiny regulators with great potential. Cell. 2001;107:823–826. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00616-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He L, Hannon GJ. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:522–531. doi: 10.1038/nrg1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawkins PG, Morris KV. RNA and transcriptional modulation of gene expression. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:602–607. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.5.5522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan Y, Zhang B, Wu T, Skogerbo G, Zhu X, et al. Transcriptional inhibiton of Hoxd4 expression by miRNA-10a in human breast cancer cells. BMC Mol Biol. 2009;10:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-10-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Younger ST, Corey DR. Transcriptional gene silencing in mammalian cells by miRNA mimics that target gene promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman RC, Farh KKH, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Research. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C, Ridzon DA, Broomer AJ, Zhou Z, Lee DH, et al. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e179. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez A, Vigorito E, Clare S, Warren MV, Couttet P, et al. Requirement of bic/microRNA-155 for normal immune function. Science. 2007;316:608–611. doi: 10.1126/science.1139253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyun S, Lee JH, Jin H, Nam J, Namkoong B, et al. Conserved MicroRNA miR-8/miR-200 and its target USH/FOG2 control growth by regulating PI3K. Cell. 2009;139:1096–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lal A, Navarro F, Maher CA, Maliszewski LE, Yan N, et al. miR-24 Inhibits cell proliferation by targeting E2F2, MYC, and other cell-cycle genes via binding to “seedless” 3′UTR microRNA recognition elements. Mol Cell. 2009;35:610–625. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stark A, Brennecke J, Bushati N, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Animal microRNAs confer robustness to gene expression and have a significant impact on 3 ′ UTR evolution. Cell. 2005;123:1133–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Yalcin A, Meyer J, Lendeckel W, et al. Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr Biol. 2002;12:735–739. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lunney JK. Advances in swine biomedical model genomics. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2007;3:179–184. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.3.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D152–157. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie SS, Li XY, Liu T, Cao JH, Zhong Q, et al. Discovery of porcine microRNAs in multiple tissues by a Solexa deep sequencing approach. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Podolska A, Kaczkowski B, Kamp Busk P, Sokilde R, Litman T, et al. MicroRNA expression profiling of the porcine developing brain. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14494. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li G, Li Y, Li X, Ning X, Li M, et al. MicroRNA identity and abundance in developing swine adipose tissue as determined by Solexa sequencing. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:1318–1328. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wernersson R, Schierup MH, Jorgensen FG, Gorodkin J, Panitz F, et al. Pigs in sequence space: a 0.66× coverage pig genome survey based on shotgun sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sawera M, Gorodkin J, Cirera S, Fredholm M. Mapping and expression studies of the mir17–92 cluster on pig Chromosome 11. Mammalian Genome. 2005;16:594–598. doi: 10.1007/s00335-005-0013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim; H-JKX-SCE-J. New porcine microRNA genes found by homology search. ProQuest Biology Journals. 2006:4. doi: 10.1139/g06-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang TH, Zhu MJ, Li XY, Zhao SH. Discovery of porcine microRNAs and profiling from skeletal muscle tissues during development. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nielsen M, Hansen JH, Hedegaard J, Nielsen RO, Panitz F, et al. MicroRNA identity and abundance in porcine skeletal muscles determined by deep sequencing. Anim Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2009.01981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li M, Xia Y, Gu Y, Zhang K, Lang Q, et al. MicroRNAome of porcine pre- and postnatal development. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rocha KM, Forti FL, Lepique AP, Armelin HA. Deconstructing the molecular mechanisms of cell cycle control in a mouse adrenocortical cell line: roles of ACTH. Microsc Res Tech. 2003;61:268–274. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeuchi Y. [Hormones and osteoporosis update. Possible roles of pituitary hormones, TSH and FSH, for bone metabolism]. Clin Calcium. 2009;19:977–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiss S, Bergland R, Page R, Turpen C, Hymer WC. Pituitary cell transplants to the cerebral ventricles promote growth of hypophysectomized rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1978;159:409–413. doi: 10.3181/00379727-159-40359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Z, Florez S, Gutierrez-Hartmann A, Martin JF, Amendt BA. MicroRNAs regulate pituitary development, and microRNA 26b specifically targets lymphoid enhancer factor 1 (Lef-1), which modulates pituitary transcription factor 1 (Pit-1) expression. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:34718–34728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.126441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bottoni A, Piccin D, Tagliati F, Luchin A, Zatelli MC, et al. miR-15a and miR-16-1 down-regulation in pituitary adenomas. J Cell Physiol. 2005;204:280–285. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amaral FC, Torres N, Saggioro F, Neder L, Machado HR, et al. MicroRNAs differentially expressed in ACTH-secreting pituitary tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:320–323. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ambros V, Bartel B, Bartel DP, Burge CB, Carrington JC, et al. A uniform system for microRNA annotation. RNA. 2003;9:277–279. doi: 10.1261/rna.2183803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yousef M, Showe L, Showe M. A study of microRNAs in silico and in vivo: bioinformatics approaches to microRNA discovery and target identification. FEBS J. 2009;276:2150–2156. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, et al. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Gelfond JA, McManus LM, Shireman PK. Reproducibility of quantitative RT-PCR array in miRNA expression profiling and comparison with microarray analysis. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:407. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willenbrock H, Salomon J, Sokilde R, Barken KB, Hansen TN, et al. Quantitative miRNA expression analysis: comparing microarrays with next-generation sequencing. RNA. 2009;15:2028–2034. doi: 10.1261/rna.1699809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bak M, Silahtaroglu A, Moller M, Christensen M, Rath MF, et al. MicroRNA expression in the adult mouse central nervous system. RNA. 2008;14:432–444. doi: 10.1261/rna.783108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farh KK, Grimson A, Jan C, Lewis BP, Johnston WK, et al. The widespread impact of mammalian MicroRNAs on mRNA repression and evolution. Science. 2005;310:1817–1821. doi: 10.1126/science.1121158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Landgraf P, Rusu M, Sheridan R, Sewer A, Iovino N, et al. A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell. 2007;129:1401–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cicatiello L, Mutarelli M, Grober OM, Paris O, Ferraro L, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha controls a gene network in luminal-like breast cancer cells comprising multiple transcription factors and microRNAs. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2113–2130. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Majid S, Dar AA, Saini S, Chen Y, Shahryari V, et al. Regulation of minichromosome maintenance gene family by microRNA-1296 and genistein in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2809–2818. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silber J, Lim DA, Petritsch C, Persson AI, Maunakea AK, et al. miR-124 and miR-137 inhibit proliferation of glioblastoma multiforme cells and induce differentiation of brain tumor stem cells. BMC Med. 2008;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smrt RD, Szulwach KE, Pfeiffer RL, Li X, Guo W, et al. MicroRNA miR-137 Regulates Neuronal Maturation by Targeting Ubiquitin Ligase Mind Bomb-1. Stem Cells. 2010 doi: 10.1002/stem.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang LL, Zhang Z, Li Q, Yang R, Pei X, et al. Ethanol exposure induces differential microRNA and target gene expression and teratogenic effects which can be suppressed by folic acid supplementation. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:562–579. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friedlander MR, Chen W, Adamidi C, Maaskola J, Einspanier R, et al. Discovering microRNAs from deep sequencing data using miRDeep. Nature Biotechnology. 2008;26:407–415. doi: 10.1038/nbt1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alexiou P, Vergoulis T, Gleditzsch M, Prekas G, Dalamagas T, et al. miRGen 2.0: a database of microRNA genomic information and regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;38:D137–141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harding CJ, Kunz S, Habibpour V, Heiz U. Microkinetic simulations of the oxidation of CO on Pd based nanocatalysis: a model including co-dependent support interactions. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2008;10:5875–5881. doi: 10.1039/b805688a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Reads distribution of sRNAs sequenced by solexa.

(TIF)

Known miRNAs identified in porcine pituitary via Solexa sequencing.

(DOC)

IsomiR of porcine pituitary.

(XLS)

Potential new miRNAs# discovered in porcine pituitary.

(DOC)

Primers used in real-time PCR.

(DOC)