Abstract

Immunohistochemistry for Fos was used to determine the role of the superior laryngeal nerve in conscious rats following water deprivation and rehydration. Adult male rats were subjected to either unilateral superior laryngeal nerve section (SLNX) or sham surgery. Two weeks later rats from each surgical group were water deprived for 48 h or water deprived for 46 h hours and given access to water for 2 h prior to perfusion. Controls were allowed ad libitum access to water. Brains were processed for Fos using a commercially available antibody. Changes in plasma osmolality and hematocrit were not significantly different between SLNX and sham following any of the treatments. Water intake in rats was not significantly affected by SLNX. In the supraoptic nucleus (SON) of sham rats, water deprivation significantly increased Fos staining while water intake following dehydration prevented this increase. Water deprivation significantly increased Fos staining in the SON of SLNX rats. Following water intake after 46 h water deprivation in SLNX rats, Fos staining in the ipsilateral SON was significantly greater than the contralateral SON and significantly lower than 48 h water deprivation. In the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) of sham rats, both water deprivation and water intake produced significant increases in Fos staining bilaterally compared to euhydrated controls. In SLNX rats, water deprivation significantly increased Fos in both ipsilateral and contralateral NTS that was not different from sham rats. SLNX significantly decreased Fos staining in the ipsilateral NTS of rats given access to water after dehydration compared to the corresponding sham treated rats. Fos staining was not affected in the contralateral NTS of SLNX rats given access to water after dehydration. This suggests that the superior laryngeal nerve contributes to changes in Fos staining in the NTS and SON following water intake in dehydrated rats.

Keywords: Supraoptic, nucleus of the solitary tract, vasopressin, oxytocin, vagus nerve

1. Introduction

The supraoptic (SON) and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus contain magnocellular neurosecretory cells that release the hormones vasopressin and oxytocin into the systemic circulation from nerve terminals in the posterior pituitary [1-3]. The regulation of the electrical activity of these neurons is critical for determining the circulating levels of both peptide hormones [4]. The physiological control of vasopressin release from the posterior pituitary is vital for the maintenance of body fluid homeostasis, and inappropriate vasopressin release contributes to the pathophysiology of several chronic disease states including congestive heart failure and hepatic cirrhosis [5-8]. Neurohypophyseal oxytocin is involved in lactation and parturition and may also play a role in sodium homeostasis [9-11]. In some species, both vasopressin and oxytocin release are regulated by plasma osmolality [4]. A number of other non-osmotic factors also influence vasopressin and oxytocin release but these mechanisms are not as well characterized.

A number of studies has demonstrated that water intake can rapidly reduce plasma vasopressin in several species including humans [12-20]. The central nervous system mechanisms mediating these effects have not been defined. Oropharyngeal cues appear to play an important role in the inhibition of vasopressin associated with water intake in many of these species [12-14, 17-19]. In contrast, the inhibition of vasopressin release after water intake is reportedly mediated by the post-absorptive signals in the rat [20, 21]. However, there have been a few observations that suggest oropharnygeal afferents participate in the regulation of magnocellular neurons in the rat. For example, a study by Shingai et al [22] demonstrated that infusions of water into the oral cavity of anesthetized rats produced an increase in urine flow and that these results were dependent on the integrity of the superior laryngeal nerves. Other investigators have shown that the application of hypertonic or hypotonic solutions into the oral cavity of anesthetized rats will increase or decrease the activity of putative magnocellular neurosecretory cells [23, 24]. We have recently observed that sham rehydration with water significantly attenuates the reduction in Fos staining in the SON that is produced when dehydrated rats drink water [25]. This suggests that pre-absorptive signals from the gastrointestinal tract or the oral cavity related to water intake do influence the activity of neurons in the SON in the rat.

The major afferents of the oral cavity include the chorda tympani branch of cranial nerve VII, the laryngeal and pharyngeal branches of cranial nerve IX in addition to the superior laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve [26]. The nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) is the primary site of termination for these afferents [26-30] and previous studies have shown that Fos staining in this region is increased by water deprivation and further increased by fluid intake [31, 32]. Preabsorptive signals related to fluid intake from the superior laryngeal nerve or other oropharyngeal and gustatory afferents would be relayed to the NTS and could contribute to the increase in Fos staining that has been observed in the NTS following water or saline ingestion.

In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that oropharyngeal afferents associated with the superior laryngeal nerve contribute to the regulation of SON magnocellular neurons and the NTS by testing the effects of chronic unilateral superior laryngeal nerve section (SLNX) on Fos staining in unanesthetized rats given access to water for 2 h after 46 h water deprivation.

2. Material and Methods

All experiments were conducted on adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (200-300 g b w, Charles Rivers). Prior to surgery, the rats were individually housed in a temperature controlled room on a 12:12 light/dark cycle with light onset at 700 h. Food and water were available ad libitum except during the experiments. All experiments using unanesthetized rats were conducted during the light phase of the LD cycle in the rat’s home cage. All procedures involving animals were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio according to NIH guidelines.

2.1 Chronic Unilateral SLNX

Each rat was anesthetized with isofluorane (drop jar) and maintained with 2% isoflurone delivered by an atomizer with O2. The left superior laryngeal nerve was accessed using a ventral midline approach. Blunt dissection was used to isolate the trachea and identify the left recurrent superior laryngeal nerve. The dorsal aspect of the superior laryngeal nerve that emerges from the distal end of the trachea was isolated and sectioned [33-35]. Controls were subjected to the same surgical procedure except the left superior laryngeal nerve was not sectioned. Water intake and body weight were monitored for 1 week following surgery. Rats were allowed a 2 week recovery period before being used in the experiments.

2.2 Protocol

Sham and unilateral SLNX rats were randomly divided into three treatment groups: euhydrated controls, 48 h water deprivation, and 46 h water deprivation with 2 h access to water prior to perfusion. The rats given water to drink prior to perfusion did not have access to food. At the end of the protocol, each rat was anesthetized with inactin (100 mg/kg ip) and perfused with 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 300-500 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Prior to the start of the perfusion, a 1-2 ml sample of whole blood was collected via cardiac puncture for measuring plasma osmolality, hematocrit, and plasma protein as previously described [31, 36]. Rats were also dissected to verify the nerve sections. The brains were removed and placed in PBS with 30% sucrose for 2-3 days. Each brain was marked on the left side (ipsilateral to the SLNX) and sectioned in a cryostat. Three sets of coronal 40 um sections were collected in cryoprotectant and store at 20°C until they were processed for immunohistochemistry. Serial sections from each forebrain and brainstem were stained for c-Fos (Rabbit anti-c-Fos Ab5, Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) as previously described [31, 36, 37]. Sections were incubated with the primary antibody (1:30,000) for 72 h at 4°C. After rinsing, the sections were processed with a biotyinlated horse anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories, Berlingame, CA) diluted 1:200 in PBS for 2 h at room temperature. Sections were reacted with an avidin-peroxidase conjugate (Vectastain ABC Kit; Vector Laboratories) and PBS containing 0.04% 3,3’–diaminobenzidine hydrochloride and 0.04% nickel ammonium sulfate for 10 to 11 minutes. Separate sets of forebrain sections also were processed for oxytocin immunofluorescence using an anti-mouse primary antibody and a Cy3 label anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:250, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). Sections were mounted on gelatin coated slides, air dried for 1-2 days and the slides were cover slipped with Permount.

Tissue sections containing regions of interest were inspected using an Olympus microscope (BX41) equipped for epifluorescence. Digital images were acquired using an Olympus DP70 camera connected to a Pentium computer running imaging software (Digital Photo Plus, v.2.2.1.227). Images were adjusted to standardize brightness and contrast. Regions of interest were identified using the rat brain stereotaxic atlas of Paxinos and Watson [38]. Four to six sections from each region were analyzed from each rat. The number of Fos positive cells in the SON or NTS was recorded bilaterally for each section. The number of Fos + oxytocin labeled cells in the SON were also averaged and analyzed for the water deprived groups. Colocalization was determined by capturing separate images using an IX50 Olympus converted to a DSU confocal microscope with an attached mercury lamp for fluorescence. The bright field Fos image was inverted and adjusted to remove background artifacts, pseudocolored green, and merged with the dark field oxytocin image to observe colocalization as previously described [25]. Artifacts placed in each brain ipsilateral to the SLNX section were used to determine whether the region was from the intact or denervated side. Data from the side of the brain ipsilateral to the nerve section were collected separately from the contralateral, intact side of the brain for later analysis.

2.3 Statistics

Data were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance with Student Newman-Keuls t-test for posthoc analysis of significant main effects (SigmaStat, v. 2.03, Systat Software Inc., Point Richmond, CA). Significance was set at P < 0.05. All values are presented as mean ± one simple SEM.

3. Results

3.1 Water Intake and Plasma Measurements

Chronic, unilateral SLNX did not significantly affect basal plasma osmolality, hematocrit or plasma protein concentration (Table 1). Water deprivation produced comparable increases in plasma osmolality, hematocrit and plasma proteins in both intact and SLNX rats (Table 1). Following water deprivation, intact and SLNX rats drank comparable amounts of water (intact 27 ± 2 ml, SLNX 24 ± 1 ml, P > 0.05) while plasma osmolality, hematocrit and plasma proteins were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Measurements of plasma osmolality, hematocrit and plasma protein from rats with ad libitum water (Cont.), 48 h water deprivation (48 h), and 46 h water deprivation followed by 2 h of rehydration (46 H + W).

| n | Osmolality mOsm | Hematocrit % | Plasma Protein (g/dL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | ||||

| Cont | 7 | 293 ± 2 | 42.7 ± 1 | 5.9 ± 0.3 |

| 48 h | 7 | 302 ± 2* | 48.0 ± 1* | 6.6 ± 0.2* |

| 46 h + W | 7 | 279 ± 1*# | 46.3 ± 1* | 5.7 ± 0.2 |

| SLNX | ||||

| Cont | 9 | 296 ± 3 | 44.6 ± 1 | 5.9 ± 0.2 |

| 48 h | 11 | 304 ± 2* | 48.7 ± 0.5* | 6.9 ± 0.2* |

| 46 h + W | 10 | 283 ± 1*# | 47.4 ± 0.5* | 6.1 ± 0.2 |

significantly different from control.

significantly different from 48 h groups. All significant differences are P < 0.05 by Student Newman-Keuls t-test.

3.2 Supraoptic Nucleus

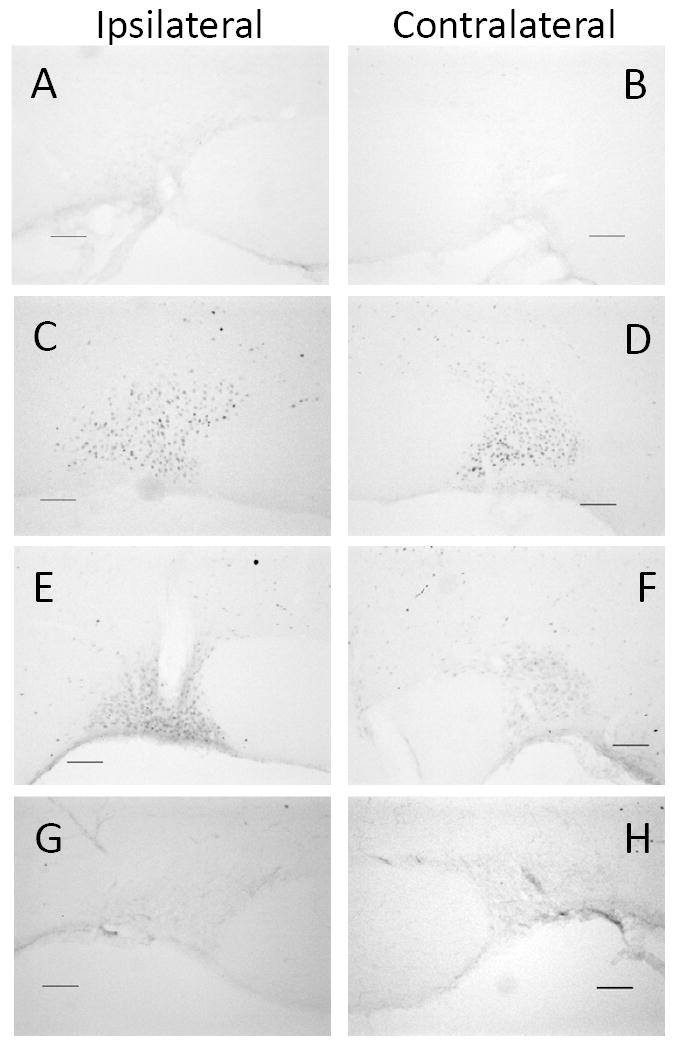

Unilateral SLNX did not appear to influence Fos staining in the SON of euhydrated controls (Figure 1 A & B) or following 48 h water deprivation (Figure 1 C & D). In both treatment conditions, Fos staining in the SON ipsilateral to the SLNX was not significantly different from either the contralateral regions from the same brains or staining observed in intact (Sham) controls (Figure 2). In contrast, Fos staining in the SON ipsilateral to the SLNX was increased as compared to the contralateral SON in rats allowed to rehydrate with water following dehydration (Figure 1 E & F) and this increase was statistically significant (Figure 2). In rats with unilateral SLNX, Fos staining in the SON on the denervated side was also increased compared to sham treated rats given water to drink (Figure 1 E & G). In water deprived rats with SLNX, 45 ± 4% of the Fos positive cells ipsilateral to the nerve section were also positive for oxytocin while 46 ± 5% of Fos positive cells on the contralateral side were oxytocin. In the SLNX rats that were water deprived for 46 h and given access to water for 2 h, Fos + oxytocin double labeling decreased to 28 ± 5% of the Fos positive cells. Representative images of Fos and oxytocin colocalization are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 1.

Digital images of representative examples of Fos staining in the supraoptic nucleus from euhydrated controls (A & B), 48 h water deprivation (C & D), and rats water deprived for 46 h and given access to water for 2 h (E-H). Images A-F are from unilateral left superior laryngeal nerve sectioned rats and G-H are from a sham surgical control. The supraoptic nuclei ipsilateral to surgical procedure are in the left column and the contralateral supraoptic nuclei are in the right column. Scale bar is 100 μm.

Figure 2.

Effects of 48 h water deprivation (48 h) and 46 h water deprivation with 2 h access to water (46 + W) on Fos staining in the supraoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus (SON) in sham surgical controls (Sham) and rats with left unilateral superior laryngeal nerve section (SLNX). Data from the SON ipsilateral to the surgical treatment (top) are presented separately from the contralateral SON (bottom). * is significantly different from euhydrated controls (Control) in the same graph. # is significantly different from 46 + W Sham and 48 h in the same graph and 46 + W SLNX in the graph below. (n = 7-11 rats per group)

Figure 3.

Representative oxytocin and Fos immunohistochemistry in the supraoptic nucleus ipsilateral to superior laryngeal nerve section following 48 h water deprivation (top) and 46 h water deprivation with 2 h access to water (bottom). Cells with both cytosolic oxytocin staining and nuclear staining for Fos are indicated by arrows. Scale bar is 10 μm.

3.3 Nucleus of the Solitary Tract

In the NTS, there was little to no Fos staining in euhydrated controls (Figure 4A & B). Water deprivation was associated with a significant increase in Fos staining in SLNX treated rats (Figure 4C & D). Unilateral SLNX did not significantly affect Fos staining observed in euhydrated controls or associated with water deprivation (Figure 5). Unilateral SLNX attenuated Fos staining in the ipsilateral NTS of rats rehydrated with water (Figure 4F) as compared to the contralateral NTS (Figure 4E) and to NTS sham treated controls (Figure 4G & H) were statistically significant (Figure 5). In the NTS contralateral to the SLNX, Fos staining in the SLNX rats was not different from sham treated rats (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Digital images of representative examples of Fos staining in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) from euhydrated controls (A & B), 48 h water deprivation (C & D), and rats water deprived for 46 h and given access to water for 2 h (E-H). Images A-F are from unilateral left superior laryngeal nerve sectioned rats and G-H are from a sham surgical control. NTS ipsilateral to surgical procedure are in the left column and the contralateral NTS are in the right column. Scale bar is 100 μm.

Figure 5.

Effects of 48 h water deprivation (48 h) and 46 h water deprivation with 2 h access to water (46 + W) on Fos staining in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) in sham surgical controls (Sham) and rats with left unilateral superior laryngeal nerve section (SLNX). Data from the NTS ipsilateral to the surgical treatment (top) are presented separately from the contralateral NTS (bottom). * is significantly different from euhydrated controls (Control) in the same graph. ˆ is significantly different from 46 + W Sham in the same graph and 46 + W SLNX and in the graph below. # is significantly different from 48 h. (n = 7-11 rats per group)

4. Discussion

The results of this study indicate that oropharyngeal afferents associated with the superior laryngeal nerve may contribute to homeostatic reflexes associated with ingestion of water. Water deprivation significantly increased Fos staining in both the SON and the NTS, while water deprivation followed by rehydration with water for two hours significantly decreased water deprivation-induced Fos staining in SON and increases Fos in NTS [31, 32]. This decrease in Fos in the SON is consistent with a decrease in plasma arginine vasopressin levels observed in our previous work [31]. Sham rehydration in the rats attenuated the decreased Fos in the SON associated with water intake suggesting that pre-absorptive and post-absorptive mechanisms contribute to this effect [25].

In the current study, SLNX did not influence Fos staining in SON of either 48 h water deprived rats or euhydrated controls. Fos staining in the SON ipsilateral to the SLNX of rats that were dehydrated and given access to water had significantly more Fos positive cells than either the contralateral SON from the same animals or similarly treated sham operated controls. This difference was not likely due to changes in water intake during the 2 h access period since SLNX and sham operated controls drank similar amounts of water and demonstrated similar changes in plasma osmolality, hematocrit, and plasma protein. Furthermore, we observed these differences between the contralateral and isplateral SONs in the SLNX treated rats. This suggests that water intake in the SLNX rats still effectively reduced Fos staining in the contralateral SON and that the putative pathway from the SLN to the SON is primarily unilateral. It should be noted that Fos staining in the SON of unilateral SLNX treated rats was still significantly reduced compared to water deprivation. This result suggests that SLNX did not eliminate all of inhibitory effects of water intake in the SON and could indicate that additional visceral afferents not related to the superior laryngeal nerve were still able to significantly influence the SON.

Our results also suggest that the role of the superior laryngeal nerve in the regulation of SON neurons associated with water intake may be greater in vasopressin than for oxytocin neurons. In sham and SLNX treated 48 h water deprived rats, nearly half of the Fos positive neurons were also oxytocin positive. In the SLNX rats exposed to water deprivation and given water, the percentage of Fos positive cells that were also oxytocin positive decreased to 28%. This suggests that SLNX may play a greater role in inhibiting vasopressin neurons than oxytocin neurons in the SON or that other pre-absorptive and post-absorptive signals related to fluid ingestion have more influence on oxytocin neurons.

Similar results were observed in the NTS. Unilateral SLNX did not influence Fos staining in either euhydrated controls or 48 h water deprived rats. SLNX significantly attenuated the increase in Fos staining in the NTS associated with water intake. The results support a role for superior laryngeal afferents in the possible activation of NTS neurons associated with fluid intake that may affect the activity of other regions of the CNS including SON.

It has recently been demonstrated that superior laryngeal afferents express both transient receptor potential channels TRPV1 and TRPV2 [39]. These channels have been shown to be activated by osmotic stimulation [40] and may provide a substrate for fluid intake to activate the superior laryngeal nerve and influence both the SON and the NTS. The superior laryngeal nerve of the rat also contains baroreceptor afferents [33, 41]. An acute increase in blood pressure is associated with water intake in rats [42]. Therefore, it is also possible that the activation of baroreceptor afferents in the superior laryngeal nerve due to the drinking pressor response contribute to the activation of the NTS and inhibition of vasopressin neurons in the SON related to water intake.

Osmo-sensitive or baroreceptor afferents from the superior laryngeal nerve would influence the NTS directly through the vagus nerve [27, 29]. The inhibitory effects of baroreceptors on the SON would involve a pathway from the NTS that could include the perinuclear zone of the SON (PNZ) and the diagonal band of Broca [43]. Information from osmo-sensitive superior laryngeal afferents also would influence the SON through the NTS and possibly the PNZ as well [25]. The NTS projects directly to the PNZ [44] but also has an extensive afferent network that includes the parabrachial nucleus and the lamina terminalis [45]. The full extent and nature of these pathways remain to be determined.

4.1 Conclusion

This study tested the role of the superior laryngeal nerve in the activation of SON and NTS neurons by water intake. Left unilateral superior laryngeal nerve section or sham treated rats were water deprived for 46 h to stimulate thirst and given access to water for 2 h. While water deprivation alone increases Fos staining in the SON and NTS, water intake following water deprivation is associated with a significant decrease in Fos in SON and a further increase in the NTS. Unilateral superior laryngeal section significantly attenuated both of these responses associated with water intake. These results suggest that afferents associated with the superior laryngeal nerve contribute to the regulation of neurohypophyseal hormone release via the NTS.

Highlights.

-

>

Unilateral section of the superior laryngeal nerve altered Fos staining related to water intake in conscious rats.

-

>

Inhibition of Fos in the supraoptic nucleus was decreased.

-

>

Increased Fos produced in the nucleus of the solitary tract was attenuated.

-

>

The superior laryngeal nerve may be a source of preabsorptive afferents related to water intake.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the technical assistance of Lisa L. Ji and Joel T. Little. This study was supported by NIH HL062579 (J.T.C).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Armstrong WE. Hypothalamic Supraoptic and Paraventricular Nuclie. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. Second Edition. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 377–90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leng G, Brown CH, Russell JA. Physiological pathways regulating the activity of magnocellular neurosecretory cells. Progress in Neurobiology. 1999;57:625–55. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renaud LP. Hypothalamic magnocellular neurosecretory neurons: intrinsic membrane properties and synaptic connections. Progress in Brain Research. 1994;100:133–7. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)60778-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourque CW. Central mechanisms of osmosensation and systemic osmoregulation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:519–31. doi: 10.1038/nrn2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oren RM. Hyponatremia in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:2B–7B. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schrier RW. Water and sodium retention in edematous disorders: role of vasopressin and aldosterone. Am J Med. 2006;119:S47–S53. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schrier RW, Fassett RG, Ohara M, Martin PY. Vasopressin release, water channels, and vasopressin antagonism in cardiac failure, cirrhosis, and pregnancy. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1998;110:407–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson HJ, Shutt LE. Syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion in a woman with preeclampsia. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2007;16:360–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amico JA, Morris M, Vollmer RR. Mice deficient in oxytocin manifest increased saline consumption following overnight fluid deprivation. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2001;281:R1368–R73. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.5.R1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bealer SL, Armstrong WE, Crowley WR. Oxytocin release in magnocellular nuclei: neurochemical mediators and functional significance during gestation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299:R452–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00217.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blackburn RE, Samson WK, Fulton RJ, Stricker EM, Verbalis JG. Central oxytocin inhibition of salt appetite in rats: evidence for differential sensing of plasma sodium and osmolality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1993;90:10380–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Appelgren BH, Thrasher TN, Keil LC, Ramsay DJ. Mechanism of drinking-induced inhibition of vasopressin secretion in dehydrated dogs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1991;261:R1226–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.5.R1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blair-West JR, Gibson AP, Sheather SJ, Woods RL, Brook AH. Vasopressin release in sheep following various degrees of rehydration. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;253:R640–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.253.4.R640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geelen G, Keil LC, Kravik SE, Wade CE, Thrasher TN, Barnes PR, et al. Inhibition of plasma vasopressin after drinking in dehydrated humans. American Journal of Physiology. 1984;247:R968–71. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.247.6.R968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang W, Sved AF, Stricker EM. Water ingestion provides an early signal inhibiting osmotically stimulated vasopressin secretion in rats. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory Integrative & Comparative Physiology. 2000;279:R756–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.3.R756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ji LL, Fleming T, Penny ML, Toney GM, Cunningham JT. Effects of water deprivation and rehydration on c-Fos and FosB staining in the rat supraoptic nucleus and lamina terminalis region. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004 doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00399.2004. 00399.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salata RA, Verbalis JG, Robinson AG. Cold water stimulation of oropharyngeal receptors in man inhibits release of vasopressin. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1987;65:561–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem-65-3-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thrasher TN, Keil LC, Ramsay DJ. Drinking, oropharyngeal signals, and inhibition of vasopressin secretion in dogs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1987;253:R509–15. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.253.3.R509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thrasher TN, Nistal-Herrera JF, Keil LC, Ramsay DJ. Satiety and inhibition of vasopressin secretion after drinking in dehydrated dogs. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1981;240:E394–401. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1981.240.4.E394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stricker EM, Hoffmann ML. Inhibition of vasopressin secretion when dehydrated rats drink water. American Journal of Physioliology: Regulatory Integrative Comparative Physiology. 2005;289:R1238–43. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00182.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stricker EM, Hoffmann ML. Presystemic signals in the control of thirst, salt appetite, and vasopressin secretion. Physiol Behav. 2007;91:404–12. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shingai T, Miyaoka Y, Shimada K. Diuresis mediated by the superior laryngeal nerve in rats. Physiol Behav. 1988;44:431–3. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(88)90048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akaishi T, Homma S. Properties of oropharyngeal/laryngeal afferents regulating vasopressin release. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1993;689:455–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb55567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saphier D. Vasopressin-secreting neurones of the paraventricular nucleus respond to oropharyngeal application of hypertonic saline. Neurosci Lett. 1990;109:97–101. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90544-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knight WD, Ji LL, Little JT, Cunningham JT. Dehydration followed by sham rehydration contributes to reduced neuronal activation in vasopressinergic supraoptic neurons after water deprivation. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2010;299:R1232–R40. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00066.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Travers JB, Travers SP, Norgren R. Gustatory neural processing in the hindbrain. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1987;10:595–632. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.10.030187.003115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalia M, Sullivan JM. Brainstem projections of sensory and motor components of the vagus nerve in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1982;211:248–65. doi: 10.1002/cne.902110304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Contreras RJ, Beckstead RM, Norgren R. The central projections of the trigeminal, facial, glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves: an autoradiographic study in the rat. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1982;6:303–22. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(82)90003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayakawa T, Takanaga A, Maeda S, Seki M, Yajima Y. Subnuclear distribution of afferents from the oral, pharyngeal and laryngeal regions in the nucleus tractus solitarii of the rat: a study using transganglionic transport of cholera toxin. Neuroscience Research. 2001;39:221–32. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(00)00218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayakawa T, Takanaga A, Tanaka K, Maeda S, Seki M. Ultrastructure of the central subnucleus of the nucleus tractus solitarii and the esophageal afferent terminals in the rat. Anatomy & Embryology. 2003;206:273–81. doi: 10.1007/s00429-002-0288-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gottlieb HB, Ji LL, Jones H, Penny ML, Fleming T, Cunningham JT. Differential effects of water and saline intake on water deprivation-induced c-Fos staining in the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1251–61. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00727.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ji LL, Gottlieb HB, Penny ML, Fleming T, Toney GM, Cunningham JT. Differential effects of water deprivation and rehydration on Fos and FosB/DeltaFosB staining in the rat brainstem. Experimental Neurology. 2007;203:445–56. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faber JE, Brody MJ. Reflex hemodynamic response to superior laryngeal nerve stimulation in the rat. 1983;9:607. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(83)90117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith DV, Hanamori T. Organization of gustatory sensitivities in hamster superior laryngeal nerve fibers. J Neurophysiol. 1991;65:1098–114. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.5.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanamori T, Kunitake T, Kato K, Kannan H. Fiber types of the lingual branch of the trigeminal nerve, chorda tympani, lingual-tonsillar and pharyngeal branches of the glossopharyngeal nerve, and superior laryngeal nerve and their relation to the cardiovascular responses in rats. Neuroscience Letters. 1996;219:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(96)13172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ji LL, Fleming T, Penny ML, Toney GM, Cunningham JT. Effects of water deprivation and rehydration on c-Fos and FosB staining in the rat supraoptic nucleus and lamina terminalis region. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R311–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00399.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howe BM, Bruno SB, Higgs KA, Stigers RL, Cunningham JT. FosB expression in the central nervous system following isotonic volume expansion in unanesthetized rats. Exp Neurol. 2004;187:190–8. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 2. New York: Academic Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okano H, Koike S, Bamba H, Toyoda K, Uno T, Hisa Y. Participation of TRPV1 and TRPV2 in the rat laryngeal sensory innervation. Neurosci Lett. 2006;400:35–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christensen AP, Corey DP. TRP channels in mechanosensation: direct or indirect activation? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:510–21. doi: 10.1038/nrn2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andrew BL. A laryngeal pathway for aortic baroceptor impulses. The Journal of Physiology. 1954;125:352–60. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoffman WE, Phillips MI, Wilson E, Schmid PG. A pressor response associated with drinking in rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1977;154:121–4. doi: 10.3181/00379727-154-39617a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grindstaff RR, Cunningham JT. Cardiovascular regulation of vasopressin neurons in the supraoptic nucleus. Experimental Neurology. 2001;171:219–26. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tribollet E, Armstrong WE, Dubois-Dauphin M, Dreifuss JJ. Extra-hypothalamic afferent inputs to the supraoptic nucleus area of the rat as determined by retrograde and anterograde tracing techniques. Neuroscience. 1985;15:135–48. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saper CB. Central Autonomic System. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. second. New York: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 107–35. [Google Scholar]