Abstract

Background

While most individuals initiate their use of tobacco prior to onset of cannabis use, recent reports have identified a smaller subset of youth who report onset of cannabis use prior to tobacco use. In this study, we characterize patterns of cannabis and tobacco use (tobacco but not cannabis, cannabis but not tobacco or both) and compare the factors associated with onset of tobacco before cannabis and cannabis before tobacco.

Methods

Data on 1812 offspring aged 12–32 years, drawn from two related offspring of Vietnam Era twin studies, were used. Individuals were divided into tobacco but not cannabis (T), cannabis but not tobacco (C) and users of both substances (CT). Those who used both could be further classified by the timing of onset of tobacco and cannabis use. Multinomial logistic regression was used to characterize the groups using socio-demographic and psychiatric covariates. Furthermore, data on parental smoking and drug use was used to identify whether certain groups represented greater genetic or environmental vulnerability.

Results

22% (n=398) reported T, 3% (n=55) reported C and 44% reported CT (n=801). Of the 801 CT individuals, 72.8% (n=583), 9.9% (n=77) and 17.3% (n=139) reported onset of tobacco before cannabis, cannabis before tobacco and onsets at the same age. C users were as likely as CT users to report peer drug use and psychopathology, such as conduct problems while CT was associated with increased tobacco use relative to T. Onset of tobacco prior to cannabis, when compared onset of cannabis before tobacco or reporting initiation at the same age was associated with greater cigarettes smoked per day, however no distinct factors distinguished the group with onset of cannabis before tobacco from those with initiation at the same age.

Conclusion

A small subset of individuals report cannabis without tobacco use. Of those who use both cannabis and tobacco, a small group report cannabis use prior to tobacco use. Follow-up analyses that chart the trajectories of these individuals will be required to delineate their course of substance involvement.

Keywords: Cannabis, Tobacco, Reverse Gateways

1. INTRODUCTION

Rates of lifetime cannabis use in those with a lifetime history of tobacco use, particularly cigarette smoking, are elevated (Agrawal et al., 2008a; Agrawal et al., 2007; Creemers et al., 2009; Duhig et al., 2005; Hofler et al., 1999; Korhonen et al., 2008a; Korhonen et al., 2010; Lewinsohn et al., 1999; Patton et al., 2006). Most trajectories involving cannabis and tobacco use begin in adolescence, commonly with tobacco use preceding or coinciding with onset of cannabis use. Due to the sequence of onsets (tobacco before cannabis) and increased likelihood of cannabis use in tobacco users, tobacco smoking has been posited as a putative `gateway' (Hawkins et al., 2002; Kandel, 1975; Kandel et al., 1993) to cannabis use. However, recent studies have begun to also identify `reverse gateways' – onsets of cannabis prior to tobacco use. For instance, a study of Australian adolescents found that regular cannabis use was associated with an 8-fold increase in likelihood of tobacco initiation in never smokers (Patton et al., 2005).

The gateway hypothesis (Kandel, 1975) posits that the relationship between a putative “gateway” drug and other drugs has three key features: sequence, association and causation (Kandel, 2003). Sequence indicates that the gateway drug must have a lower age at initiation than other drugs. Association reflects a higher risk of using those other drugs in gateway drug users. Causation, controversially, implies that the gateway drug has a direct, causal impact on the subsequent likelihood of other drug use.

The gateway theory is fairly well studied, with cannabis being implicated as a potential “gateway” to use of other illicit drugs, such as cocaine (Grant et al., 2010; Lessem et al., 2006; Lynskey et al., 2006; Lynskey et al., 2003) and tobacco use, particularly cigarette smoking serving as a potential gateway to cannabis use (Kandel, 2002). Recently, however, investigators have begun to investigate and characterize “reverse gateways” (Patton et al., 2005; Van et al., 2010). These reflect a scenario where the sequence of onset of a set of psychoactive substances occurs in an order that is reverse to normative patterns. For instance, while in a majority of instances, tobacco use precedes cannabis use, reverse gateways reflect scenarios in which onset of cannabis precedes onset of tobacco. For instance, Tarter and colleagues (Tarter et al., 2006) found that a subset of youth initiated use of cannabis prior to use of alcohol/tobacco and that this “reverse” pattern was associated with neighborhood disadvantage, greater drug accessibility and neglectful parents.

While the concept of reverse gateways relies primarily on sequence of onsets, there is also growing support for association in both gateways and reverse gateways. For instance, tobacco smokers who use cannabis are more likely to be daily smokers and develop nicotine dependence (Agrawal et al., 2008a; Degenhardt et al., 2010; Korhonen et al., 2008a; Korhonen et al., 2010; Timberlake et al., 2007b). Likewise, tobacco and blunt users are more likely to progress beyond the preliminary stages of cannabis experimentation to more frequent use (Ream et al., 2008; Timberlake, 2009). Given the ease of availability and fairly common use of both psychoactive substances and the public health challenges they impose, the goal of the present study is to replicate and extend prior research on identification and characterization of the sequence of onsets of cannabis and tobacco use. We replicate prior evidence for the presence of both gateways and reverse gateways and extend the extant literature by characterizing these groups using numerous psychiatric covariates and an index of genetic vulnerability. The study has two goals:

-

(a)

First, we identify groups of individuals who use tobacco but not cannabis (T), cannabis but not tobacco (C) and those who report lifetime use of both cannabis and tobacco (CT). We, then, distinguish C, T and CT individuals in terms of socio-demographic characteristics, comorbid psychopathology and genetic vulnerability.

-

(b)

Second, we classify the CT individuals into 3 groups: those using tobacco before cannabis (gateways), cannabis before tobacco (reverse gateways) and those using both substances for the first time at the same age. Socio-demographic, psychopathology and genetically informative measures are used to distinguish individuals in these groups from each other.

2. METHODS

2.1. Sample

Data for this study come from 1919 offspring of fathers who were members of the Vietnam Era Twins Registry (VETR) (Eisen et al., 1987; Goldberg et al., 1987; Henderson et al., 1990). In 1992, twins were interviewed by telephone with the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS-IIIR) (Robins et al., 1988). In 2001 and 2004 respectively, data collection was initiated from two offspring-of-twins (OOT) studies, which aimed to examine outcomes in the children of VETR twin fathers (and their spouses) who (a) were concordant or discordant for alcohol dependence (AD, Project 1), and (b) were concordant or discordant for illicit drug dependence (DD, Project 2), along with (c) unaffected control twin pairs. Both OOT projects used an adaptation of the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA)(Bucholz et al., 1994b) to collect data from mothers and offspring via telephone administration. For both projects, biological mothers or custodial mothers (e.g. step mothers) were eligible to participate if twins provided permission to contact them. Offspring were eligible to participate if the VETR twin father and biological and/or custodial mothers gave permission to contact them (In Project 2, permission was granted by the VETR twin father). Parents provided written consent for their minor aged offspring to be interviewed. Consent rates for the OOT studies ranged from 81% (for mothers) to 85.4% (for offspring with consent from both parents) – details may be found in a related publication (Scherrer et al., 2004).

Descriptions of survey contents and response rates may be found in related publications (Duncan et al., 2008; Jacob et al., 2003; Scherrer et al., 2004). A total of 1919 (50.5% female) offspring aged 12–32 years (mean 21.3, SD=4.3) completed the interviews. However, for these analyses, we excluded 107 subjects who were not queried about their age at first cannabis use due to an inadvertent skip out (that excluded individuals reporting < 6 instances of cannabis use from reporting an age at 1st use) that occurred early in the interview process and was subsequently corrected. Thus, analyses are presented here on 1812 subjects.

2.2 Measures

Measures were assessed using self-reported responses to an interview based on the Semi-Structured Assessment of the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA) (Bucholz et al., 1994a).

2.2.1. Cannabis and tobacco use

Lifetime use (ever used even once) of cannabis and cigarettes, along with age at 1st use is used. For tobacco use, only cigarette use was queried.

2.2.2. Covariates

Multiple covariates were used to distinguish C, T and CT individuals and further to, distinguish between those who used cannabis before tobacco from those who used tobacco before cannabis. Detailed covariate descriptions are available in Table 1. Briefly, the covariates could be classified as:

-

(a)

Socio-demographic (age at interview, born after 1981, sex, Caucasian ethnicity);

-

(b)

Peer and parenting measures (current peer smoking, current peer drug use, perceived strictness of parents during childhood);

-

(c)

Smoking-related measures (age at 1st cigarette, DSM-IV nicotine dependence diagnosis, current smoking, maximum cigarettes smoked in a 24 hour period, 40 or more cigarettes per day and 3 or more attempts to quit for 2 weeks or longer);

-

(d)

Cannabis-related covariates (age at 1st use, DSM-IV cannabis abuse/dependence, used 40+ times and current cannabis use);

-

(e)

Psychopathology (other illicit drug use, conduct problems and DSM-IV diagnoses of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, alcohol abuse/dependence, ever got drunk, weekly got drunk, panic disorder and social phobia);

-

(f)

Familial history of nicotine or drug dependence which could be further disentangled into genetic versus familial environmental vulnerability using the offspring-of-twins design.

Regarding (f), the OOT design assigns offspring to 4 groups: offspring whose father is nicotine dependent (or drug dependent) are at high genetic and high environmental risk. In comparison, offspring whose father are unaffected but their father's identical/monozygotic twin is affected are at high genetic (as their MZ uncle shares all his genes identical-by-descent with their father) and low environmental (as they do not share family environment with the affected uncle) risk. Likewise, if the offspring's father in unaffected by their father's fraternal/dizygotic twin in affected then the offspring is at intermediate genetic and low environmental risk. These offspring are compared to offspring from pairs of twin fathers where neither twin father is affected (low genetic and low environmental risk) to determine the relative contributions of genetic and familial environmental vulnerability to each group of C, T and CT users.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 1812 offspring of Vietnam Era Twins, stratified by their cannabis and tobacco use behaviors.

| Covariate | Neither Tobacco nor Cannabis (N=558) | Cigarettes only (N=398) | Cannabis only (N=55) | Both (N=801) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco 1st (N=583) | Cannabis 1st (N=79) | ||||

| Socio-demographic | |||||

| Age at interview < 21 years | 69.7 | 46.7 | 52.7 | 39.3 | 36.7 |

| Born after 1981 | 62.3 | 33.2 | 36.4 | 25.6 | 24.1 |

| Sex (Male) | 45.9 | 48.0 | 58.2 | 51.3 | 62.0 |

| Caucasian | 91.9 | 92.7 | 89.1 | 93.3 | 96.2 |

| Peers and parenting | |||||

| Current Peer smoking (yes/no) | 27.0 | 54.7 | 49.1 | 80.4 | 69.2 |

| Current Peer drug use (yes/no) | 34.4 | 57.4 | 85.5 | 93.3 | 84.6 |

| Parents were strict when child | 52.0 | 62.1 | 61.8 | 53.7 | 59.5 |

| Smoking related covariates # | |||||

| Age at 1st cigarette < 13 years | - | 20.1 | - | 34.3 | 2.5 |

| DSM-IV Nicotine dependence | - | 6.5 | - | 24.7 | 13.9 |

| Current smoker (in past 12 months) | - | 78.2 | - | 84.8 | 88.6 |

| Maximum cigarettes in 24 hours (40 or more) | - | 6.3 | - | 23.7 | 13.9 |

| Cigarettes per day (40 or more) | - | 2.8 | - | 12.0 | 7.8 |

| Quit for 2 or more weeks (3 or more times) | - | 37.6 | - | 41.6 | 47.1 |

| Cannabis related covariates # | |||||

| Age at 1st cannabis use < 15 years | - | - | 14.6 | 22.1 | 43.0 |

| DSM-IV cannabis abuse/dependence | - | - | 12.7 | 33.3 | 33.0 |

| Current cannabis use (in past 12 months) | - | - | 43.4 | 44.2 | 49.3 |

| Used cannabis 40+ times lifetime | - | - | 10.9 | 38.1 | 39.2 |

| Other psychopathology | |||||

| Other illicit drug use | 2.7 | 4.5 | 36.4 | 58.8 | 63.3 |

| DSM-IV conduct problems | 3.1 | 6.5 | 23.6 | 27.3 | 31.7 |

| DSM-IV ADHD (maternal report) | 11.1 | 16.1 | 15.6 | 18.8 | 17.5 |

| DSM-IV major depressive disorder | 9.1 | 11.3 | 18.2 | 23.5 | 21.5 |

| DSM-IV Generalized anxiety disorder | 1.8 | 5.3 | 9.1 | 7.9 | 3.8 |

| DSM-IV alcohol abuse/dependence | 2.9 | 21.7 | 32.7 | 55.3 | 45.6 |

| Ever got drunk | 22.8 | 66.1 | 74.6 | 93.7 | 89.9 |

| Weekly drunkenness | 1.1 | 12.3 | 20.0 | 32.9 | 29.1 |

| DSM-IV panic disorder | 6.0 | 8.3 | 10.9 | 14.6 | 15.2 |

| DSM-IV social phobia | 26.7 | 30.2 | 23.6 | 34.1 | 32.9 |

| Familial Vulnerability to Nicotine Dependence | |||||

| High genetic & High environmental risk | 71.8 | 68.0 | 73.3 | 65.3 | 81.0 |

| High genetic & Low environmental risk | 24.9 | 21.6 | 29.4 | 22.1 | 40.0 |

| Intermediate genetic & high environmental risk | 29.4 | 28.1 | 29.4 | 25.6 | 40.0 |

| Familial Vulnerability to Drug Dependence | |||||

| High genetic & High environmental risk | 24.3 | 24.5 | 30.4 | 18.9 | 17.9 |

| High genetic & Low environmental risk | 10.5 | 10.4 | 18.0 | 6.2 | 11.3 |

| Intermediate genetic & high environmental risk | 7.3 | 8.2 | 5.9 | 6.6 | 8.3 |

2.3 Analyses

The goal of this study was to identify and distinguish C, T and CT users and further, in the CT users to identify correlates of those using cannabis and tobacco at the same age versus cannabis before tobacco and tobacco before cannabis. All statistical analyses were conducted in STATA, using multinomial logistic regression. Robust standard errors were computed using a variance estimator that allowed for familial clustering due to inclusion of siblings.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Sample characteristics

In our sample, 66.2% (n=1199) and 47.2% (n=856) of the participants reported lifetime use (even once) of cigarettes and cannabis respectively. Twenty-nine percent (n=558) of the participants used neither substance while 44.2% (N=801) used both (CT). Of those who had ever smoked, 66.8% reported lifetime smoking 21+ cigarettes, 8.3% reported ever smoking 40 cigarettes/day and 17.7 % met criteria for DSM-IV nicotine dependence. Of those who had smoked at least 21 cigarettes, 83.6% reported smoking in the past 12 months.

Of those who used cannabis even once, 45% reported use in the past 12 months, 37.7% reported using cannabis 40+ times during their lifetime and 34.2% met criteria for DSM-IV abuse/dependence.

3.2 Correlates of lifetime cannabis and/or tobacco use?

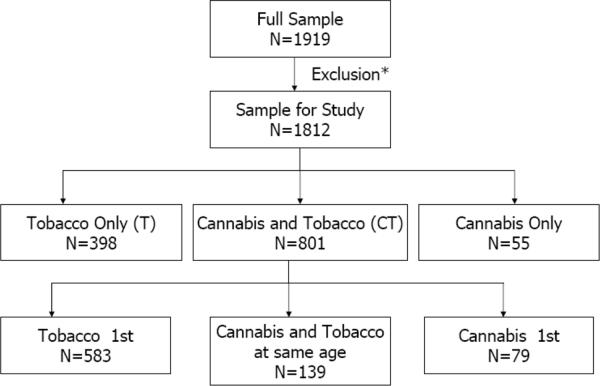

Figure 1 shows the number of individuals who could be classified as cannabis only (C), tobacco cigarettes only (T) and users of both cannabis and tobacco (CT). Table 1 shows the prevalence of, while Table 2 shows associations with putative correlates of cannabis and tobacco use. Those who used neither substance serve as the reference group. With rare exception, when contrasted with using neither, CT was most highly associated with covariates indexing peer substance use and psychopathology. Comparisons of C and T users revealed stronger associations with covariates such as current peer drug use, other illicit drug use as well as several measures of psychopathology, including conduct problems, major depressive disorder and alcohol abuse/dependence in C compared with T. For instance, current peer drug use, conduct disorder and major depressive disorder were equally associated with C and CT but were associated with T to a considerably lesser degree. In contrast, peer cigarette smoking was equally associated with C and T but considerably more common in CT. Importantly, compared with C or T, those reporting CT were significantly more likely to report earlier age at initiation of cannabis and/or tobacco and demonstrate elevated likelihood of heavier smoking (cigarettes per day and maximum cigarettes in a 24 hour period), nicotine dependence and cannabis abuse/dependence.

Figure 1.

Patterns of cannabis of tobacco use in 1812 offspring, aged 12–32 years of Vietnam Era Twins.

*We excluded 107 subjects who were not queried about their age at first cannabis use due to an inadvertent skip out.

Table 2.

Multinomial odds-ratios (95% C.I.) between lifetime use of cigarettes, cannabis or both, relative to using neither (N=558) in 1812 participants from two offspring of twin studies.

| Covariate | BOTH (N=801) | Cigarettes only (N=398) | Cannabis only (N=55) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic | |||

| Age at interview < 21 years | 0.29 (0.23 – 0.37)*a | 0.38 (0.29 – 0.50)*b | 0.48 (0.28 – 0.85)*a,b |

| Sex (Male) | 1.28 (1.03 – 1.58)* | 1.09 (0.84 – 1.41) | 1.64 (0.94 – 2.87) |

| Caucasian | 1.17 (0.78 – 1.76) | 0.97 (0.61 – 1.55) | 0.72 (0.29– 1.76) |

| Born after 1981 | 0.22 (0.18–0.28)*b | 0.30 (0.23–0.40)*a | 0.35 (0.20–0.62)*ab |

| Peers and parenting | |||

| Current Peer smoking (yes/no) | 9.38 (7.64 – 12.65)* | 3.26 (2.49 – 4.28)*b | 2.61 (1.49 – 4.57)*b |

| Current Peer drug use (yes/no) | 23.87 (17.37 – 32.80)*a | 2.58 (1.98 – 3.36)* | 11.23 (5.19 – 24.25)*a |

| Parents were strict when child | 1.10 (0.89 – 1.37) | 1.51 (1.16 – 1.96)*b | 1.50 (0.85 – 2.64)b |

| Smoking related covariates # | |||

| Age at 1st cigarette < 13 years | 1.44 (1.08 – 1.91)* | Ref | - |

| DSM-IV Nicotine dependence | 4.06 (2.65 – 6.23)* | Ref | - |

| #DSM-IV ND symptoms | 1.53 (1.41 – 1.65)* | Ref | - |

| Current smoker (in past 12 months) | 1.59 (1.00 – 2.52)* | Ref | - |

| Maximum cigarettes in 24 hours (40 or more) | 4.11 (2.65 – 6.37)* | Ref | - |

| Cigarettes per day (40 or more) | 4.29 (2.27 – 8.09)* | Ref | - |

| Quit for 2 or more weeks (3 or more times) | 1.16 (0.77 – 1.75) | Ref | - |

| Cannabis related covariates # | Ref | ||

| Age at 1st cannabis use < 15 years | 2.44 (1.15 – 5.18)* | - | Ref |

| DSM-IV cannabis abuse/dependence | 2.68 (1.46 – 4.94)* | - | Ref |

| Current cannabis use (in past 12 months) | 1.09 (0.62 – 1.89) | - | Ref |

| Used cannabis 40+ times lifetime | 5.35 (2.26–12.63)* | - | Ref |

| Other psychopathology | |||

| Other illicit drug use | 54.13 (31.79–92.17)* | 1.72 (0.85–3.44) | 20.69 (9.75–43.87)* |

| DSM-IV conduct problems | 11.98 (7.21 – 19.90)*a | 2.20 (1.17 – 4.14)* | 9.79 (4.46 – 21.53)*a |

| DSM-IV ADHD (maternal report) | 1.73 (1.21 – 2.46)*a | 1.54 (1.01 – 2.33)*a | 1.48 (0.63 – 3.48) |

| DSM-IV major depressive disorder | 3.13 (21.5–4.40)*a | 1.27 (0.83 – 1.94) | 2.21 (1.10 – 4.64)*a |

| DSM-IV Generalized anxiety disorder | 4.60 (2.34 – 9.05)*a | 3.05 (1.42 – 6.56)*a | 5.48 (1.81 – 16.66)*a |

| DSM-IV alcohol abuse/dependence | 38.8 (23.20–65.18)* | 9.40 (5.41–16.32)* | 16.48 (7.77–34.94)* |

| Ever got drunk | 44.3 (31.71 – 61.88)* | 6.61 (4.96 – 8.81)*a | 9.94 (5.25 – 18.82)*a |

| Frequency of drinking to intoxication | 42.48 (18.74 – 96.28)*b | 12.92 (5.48 – 30.48)*a | 23.0 (8.12 – 65.18)*ab |

| DSM-IV panic disorder | 2.65(1.77–4.00)* | 1.43 (0.86 – 2.37) | 1.93 (0.77 – 4.84) |

| DSM-IV social phobia | 1.39(1.09 – 1.76)* | 1.18 (0.89 – 1.58) | 0.85 (0.44 – 1.63) |

| Familial Vulnerability to Nicotine Dependence | |||

| High genetic & High environmental risk | 0.82 (0.63–1.05) | 0.83 (0.61–1.14) | 1.08 (0.54–2.16) |

| High genetic & Low environmental risk | 0.88 (0.57–1.38) | 0.83 (0.49–1.43) | 1.26 (0.42–3.78) |

| Intermediate genetic & high environmental risk | 0.85 (0.56–1.28) | 0.94 (0.58–1.52) | 1.00 (1.00–2.99)$ |

| Familial Vulnerability to Drug Dependence | |||

| High genetic & High environmental risk | 0.79 (0.59–1.03) | 1.01 (0.73–1.40) | 1.36 (0.70–2.64)$ |

| High genetic & Low environmental risk | 0.73 (0.59–1.03) | 0.99 (0.73–1.40) | 1.87 (0.77–4.50)$ |

| Intermediate genetic & high environmental risk | 1.01 (0.63–1.64) | 1.13 (0.64–1.99) | 0.79 (0.18–3.48) |

statistically significant at p < 0.05

p<0.10

identical numerical superscripts indicate odds-ratios that are statistically equal to each other.

identical numerical superscripts indicate odds-ratios that are statistically equal to each other.

As these odds-ratios cannot be computed by using the never-user group as the reference group (e.g. those who never use cannabis always have a '0' for cannabis abuse/dependence), comparisons are made using the solo-user group as the reference group (indicated as 'Ref').

We also examined whether offspring at varying degrees of genetic and environmental risk (due to their father or uncle's nicotine or drug dependence) were overrepresented in any one group relative to the group of individuals using neither cannabis nor tobacco. None of the associations approached significance at p < 0.05, however there was suggestive evidence that the C group represented individuals with higher genetic (and environmental) vulnerability to drug dependence.

3.3 Order of onset of tobacco and cannabis use

The mean age of tobacco and cannabis initiation was 14.3 [SD 3.1, range 5–25 years] and 16.0 [SD 2.4, range 3–27 years] respectively. As shown in Figure 1, of the 801 CT individuals, 17.3% (n=139) reported onset of cannabis and tobacco use in the same year (i.e. at the same age), 72.8% (n=583) reported initiating tobacco use before cannabis use while 9.9% (n=77) reported using cannabis at an earlier age than tobacco. Onsets were, on average, 3.1 (tobacco before cannabis) and 2.2 (cannabis before tobacco) years apart, respectively.

3.4 Correlates of cannabis before tobacco and tobacco before cannabis use

Table 1 shows the prevalence of, while Table 3 shows the association between multiple covariates and onset orders – those initiating at the same age serve as the reference group. There were limited statistical differences between those reporting cannabis and tobacco initiation at the same age compared with those reporting onset of tobacco before cannabis and cannabis before tobacco. Onset of tobacco use before cannabis use was associated with lower age at first cigarette use (and a corresponding higher age at cannabis use)and a greater number of cigarettes smoked per day. On the other hand, onset of cannabis prior to tobacco was associated with fewer nicotine dependence symptoms and a lower likelihood of perceived current peer drug use. None of these differences could be attributed to an earlier age at initiation (e.g. fewer nicotine dependence symptoms were noted even after adjusting for later age at 1st cigarette use on these individuals). Compared with those initiating cannabis and tobacco use at the same age, those using cannabis before tobacco were less likely to be offspring at high genetic risk for drug dependence.

Table 3.

Multinomial odds ratios (95% C.I.) between exhibiting gateways (onset of cigarettes before cannabis) or reverse gateways (onset of cannabis before cigarettes), relative to onset at the same age (N=139) in 801 participants reporting a lifetime history of both cannabis and cigarette use.

| Covariate | Gateway (N=583) | Reverse (N=79) |

|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic | ||

| Age at interview < 21 years | 0.76 (0.52 – 1.11) | 0.68 (0.39 – 1.20) |

| Sex (Male) | 1.04 (0.72 – 1.51) | 1.61 (0.92 – 2.83) |

| Caucasian | 1.57 (0.82 – 2.97) | 2.84 (0.79 – 10.20) |

| Born after 1981 | 0.67 (0.45–1.00)*a | 0.62 (0.33–1.16)a |

| Peers and parenting | ||

| Peer smoking (yes/no) | 1.34 (0.87 –1.34) | 0.74 (0.40 – 1.36) |

| Peer drug use (yes/no) | 0.86 (0.39 – 1.87) | 0.34 (0.13 – 0.87)* |

| Parents are strict | 0.86 (0.59 – 1.25) | 1.12 (0.64 – 1.96) |

| Cigarette smoking related covariates | ||

| Age at 1st cigarette < 13 years | 6.07 (3.21 – 11.52)* | 0.30 (0.07 – 1.40) |

| DSM-IV Nicotine Dependence | 1.13 (0.73 – 1.76) | 0.56 (0.26 – 1.18) |

| #DSM-IV ND symptoms | 1.03 (0.94 – 1.13) | 0.80 (0.69 – 0.94)* |

| Current smoker (in past 12 months) | 1.02 (0.55 – 1.88) | 1.43 (0.48 – 1.21) |

| Maximum cigarettes in 24 hours (40 or more) | 1.49 (0.92 – 2.41) | 0.78 (0.36 –1.68) |

| Cigarettes per day (40 or more) | 1.36 (1.02 – 1.82)* | 1.09 (0.67 – 1.76) |

| Quit for 2 or more weeks (3 or more times) | 1.11 (0.68 – 1.82) | 1.39 (0.62 – 3.11) |

| Cannabis related covariate | ||

| Age at 1st cannabis use < 15 years | 0.49 (0.33 – 0.73)* | 1.30 (0.74 – 2.29) |

| DSM-IV cannabis abuse/dependence | 0.81 (0.68 – 0.97)* | 0.77 (0.58 – 1.06) |

| Current cannabis use (in past 12 months) | 0.85 (0.54–1.23) | 1.05 (0.59–1.86) |

| Used cannabis 40+ times lifetime | 0.72 (0.50–1.05) | 0.76 (0.43–1.33) |

| Other psychopathology | ||

| Other illicit drug use | 0.85 (0.58–1.25) | 1.03 (0.58–1.83) |

| DSM-IV conduct problems | 1.07 (0.70 – 1.63) | 1.32 (0.72 – 2.43) |

| DSM-IV ADHD | 1.51 (0.82 – 2.78) | 1.40 (0.58 – 3.39) |

| DSM-IV major depressive disorder | 0.73 (0.38 – 1.40) | 0.82 (0.54 – 1.24) |

| DSM-IV Generalized anxiety disorder | 0.83 (0.43 – 1.58) | 0.38 (0.11 – 1.39) |

| DSM-IV alcohol abuse/dependence | 0.83 (0.48 – 1.44) | 1.22 (0.84 – 1.76) |

| Ever got drunk | 1.39 (0.71–2.75) | 0.84 (0.33–2.15) |

| Frequency of drinking to intoxication | 1.31 (0.87–1.97) | 1.09 (0.59–2.01) |

| DSM-IV panic disorder | 1.21 (0.55 – 1.65) | 1.15 (0.66 – 1.99) |

| DSM-IV social phobia | 1.06 (0.59– 1.91) | 1.12 (0.75 – 1.66) |

| Familial Vulnerability to Smoking | ||

| High genetic & High environmental risk | 1.56 (0.84–2.88)$ | 0.78 (0.53–1.14) |

| High genetic & Low environmental risk | 1.79 (0.91–3.49)$ | 0.82 (0.55–1.23) |

| Intermediate genetic & high environmental risk | 2.30 (0.75–7.06) | 1.19 (0.57–2.48) |

| Familial Vulnerability to Drug Dependence | ||

| High genetic & High environmental risk | 0.62 (0.29–1.31) | 0.66 (0.41–1.06)$ |

| High genetic & Low environmental risk | 0.82 (0.31–2.22) | 0.43 (0.21–0.87)* |

| Intermediate genetic & high environmental risk | 0.77 (0.25–2.38) | 0.60 (0.28–1.27) |

statistically significant at p < 0.05

p<0.10

identical numerical superscripts indicate odds-ratios that are statistically equal to each other.

identical numerical superscripts indicate odds-ratios that are statistically equal to each other.

4. DISCUSSION

In a sample of 1812 offspring of twins, we identified individuals who used tobacco but not cannabis (T), cannabis but not tobacco (C) and those who used both cannabis and tobacco (CT) during their lifetime. Using both cannabis and tobacco was associated with heavier and more problematic tobacco and cannabis use as well as with higher rates of psychopathology. Cannabis (but not tobacco) use was strongly associated with conduct disorder, major depression and peer drug use. In those reporting cannabis and tobacco use, a minority reported using cannabis prior to tobacco (reverse gateways) – these individuals were distinguished by fewer nicotine dependence symptoms.

4.1 Patterns and correlates of cannabis and tobacco use

Consistent with the literature, we found support for increased associations between CT and psychopathology (Korhonen et al., 2010). Compared with C and T, those who reported CT were also more likely to report cannabis and nicotine dependence respectively – this has been reported across multiple samples (Agrawal et al., 2008a; Agrawal et al., 2008b; Agrawal et al., 2010; Degenhardt et al., 2010; Huizink et al., 2010; Timberlake et al., 2007a; Wittchen et al., 2007). However, we also found that C was associated with other drug use and conduct disorder to the same degree as CT. This is somewhat contradictory to the findings of Suris et al (Suris et al., 2007) – while we do find comparably higher rates of problem behaviors when comparing C to those using neither cannabis nor tobacco, unlike Suris and colleagues, in our study, C was not associated with an appreciable decrease in problem behaviors. However, T users did show a somewhat lower vulnerability to comorbid psychopathology compared with CT users.

4.2 Gateways and Reverse Gateways

To our knowledge, this is one of few studies that aims to distinguish gateways from reverse gateways. Initiation of tobacco use before cannabis (gateways) was associated with lower age at first cigarette smoking [13.1 vs 14 years in the full sample] and with greater likelihood of smoking 40+ cigarettes per day. Genetic vulnerability to nicotine dependence, as indexed by a history of nicotine dependence in the biological father or his identical co-twin, was more likely to contribute to using tobacco prior to cannabis. In contrast, despite early age at cannabis initiation [mean of 14.7 years, compared with 16 years in the full sample], onset of cannabis prior to tobacco use (reverse gateways) appeared to only be related to fewer nicotine dependence symptoms and a lower likelihood of peer drug use. Perhaps the most intriguing association distinguishing reverse gateways was with self-reported peer substance use. Compared to those starting to use cannabis and tobacco at the same age, those using cannabis before tobacco were 0.3 times less likely to report current peer drug use. This is consistent with the pivotal and often overwhelming influence of perceived peer substance involvement over other competing covariates in predicting concomitant use of cannabis and tobacco (Agrawal et al., 2007; Creemers et al., 2010; Ellickson et al., 2004; Korhonen et al., 2008a). However, unlike Tarter et al., 2006, we did not find a clear excess of risk in those showing reverse gateways. This may be attributable to absence of covariates such as neighborhood deprivation and parental neglect that were informative in distinguishing reverse gateways in that study. In these data, there is no consistent indication of systematic associations between covariates and initiation of cannabis prior to tobacco. Whether this indicates that these individuals simply have “unusual” patterns of drug use or that other unmeasured influences act on reverse gateways, remains to be seen. Here, it will be important to examine the substance use trajectories of individuals who use cannabis prior to tobacco and vice versa to examine whether differential outcomes emerge in these individuals across the lifespan.

4.3 Mechanisms underlying cannabis and tobacco (co)-use

While it is relatively uncommon for adolescents to use cannabis without a prior history of tobacco use (Kandel et al., 1993), our analyses suggest that cannabis without tobacco use is associated with other problem behaviors. However, even the lifetime use of both substances is associated with greater likelihood of nicotine and cannabis abuse/dependence. This cross-substance risk has been variously attributed to (a) shared genetic and environmental vulnerabilities to tobacco and cannabis use (Agrawal et al., 2008b; Agrawal et al., 2010; Huizink et al., 2010; Neale et al., 2006); (b) other shared risk factors, such as a vulnerability to externalizing problems (Korhonen et al., 2008b; Korhonen et al., 2010) or environmental risks, such as delinquent peer affiliations (Andrews et al., 2002); (c) a common route of administration (i.e. via inhalation) (Agrawal et al., 2009) and the consequent adaptation of the respiratory system facilitating more frequent use (Aldington et al., 2007); (d) co-use of the two substances in joints and blunts (Kelly, 2005) and (e) more controversially, to causal influences.

Despite evidence for shared risk and protective influences on cannabis and tobacco (particularly, smoked forms), the relationship between these drugs appears to extend well beyond overlapping etiologies. For instance, in a recent study, Korhonen and colleagues (2010) noted that even after adjusting for externalizing behaviors and familial risk, initiation of cigarette use prior to age 12 was associated with a significantly increased risk of cannabis initiation. This is also consistent with findings in a U.S. sample where cannabis-using women were more likely to progress from cigarette use to regular smoking and further, to dependence, and that this elevation in risk persisted after control for multiple psychiatric covariates (Agrawal et al., 2008a). Thus, while shared factors may contribute to drug comorbidity, to some extent, the robust associations between cannabis and tobacco are unique.

4.4 Limitations

Some limitations of this study are noteworthy. First, this is an offspring of twins design where biological fathers were alcohol or drug dependent (or unaffected). While this raises the possibility of lack of generalizability, the study design measures did not correlate with outcomes. Second, the age range of the participants was such that some younger individuals may not be past the risk period for onset of cannabis and tobacco. However, adjusting for young age (under 17 years, typically the median onset age for cannabis use) did not alter conclusions. Third, these results are reported on a U.S. sample and may not be observed in other countries (deKort, 1994). Fourth, cohort effects may have influenced patterns of substance use in this study — with the wide age spread and recent changes in social norms regarding both cigarettes and cannabis, future studies may find increased evidence for reverse gateways. Finally, these data are retrospective and cross-sectional in nature and as such, limited by recall biases. For instance, CT individuals may have used cannabis just once while smokers may have continued smoking — we propose to use longitudinal data to address this limitation in the future.

4.5 Conclusion

Cannabis continues to be the most commonly used illicit drug in developed nations (Degenhardt et al., 2008) while the highly addictive properties of nicotine make it a leading global health hazard (Mackay et al., 2006). Even when used separately, these substances appear to contribute widely to public health problems, but their co-occurring use is particularly problematic. In educating adolescents about general substance use, specific attention should be paid to the use of cigarettes and cannabis, separately and in tandem. Awareness regarding the exacerbation of the addictive potential of each of these substances when using the other should be underscored.

Highlights

In a sample of 1812 individuals, cannabis and tobacco use was reported by 44% of the sample.

A majority of those using both drugs reported onset of tobacco prior to cannabis.

Those using cannabis but not tobacco were equally likely as those using both to report other psychopathology.

There were no distinguishing characteristics of those who used cannabis prior to tobacco.

Acknowledgements

None

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health: DA23668, DA020810, DA18660, DA14363, DA18267 and from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), grants AA11667, AA11822, AA007580, and AA11998 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), and from a Merit Review Grant (Jacob) from the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Research Service. The United States Department of Veterans Affairs has provided financial support for the development and maintenance of the VET Registry. None of the funding agencies were involved in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors: AA, JFS, MTL and HX conceptualized, analyzed and prepared the first drafts of the manuscript. CES, JDG, JRH, PAFM, TJ and KKB provided feedback on covariate selection and interpretation of analyses. TJ and KKB also collected data for the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript prior to submission.

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- Agrawal A, Madden P, Bucholz K, Heath A, Lynskey M. Transitions to Regular Smoking and to Nicotine Dependence in Women using Cannabis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008a;95:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. Tobacco and cannabis co-occurrence: does route of administration matter? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, Heath AC. Correlates of cannabis initiation in a longitudinal sample of young women: the importance of peer influences. Prev Med. 2007;45:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT, Pergadia ML, Bucholz KK, Heath AC, Martin NG, Madden PA. Early cannabis use and DSM-IV nicotine dependence: a twin study. Addiction. 2008b;103:1896–1904. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Silberg JL, Lynskey MT, Maes HH, Eaves LJ. Mechanisms underlying the lifetime co-occurrence of tobacco and cannabis use in adolescent and young adult twins. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldington S, Williams M, Nowitz M, Weatherall M, Pritchard A, McNaughton A, Robinson G, Beasley R. Thorax. 2007. The effects of cannabis on pulmonary structure, function and symptoms. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Tildesley E, Hops H, Li F. The influence of peers on young adult substance use. Health Psychol. 2002;21:349–357. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, Jr., Reich T, Schmidt I, Schuckit MA. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. J Stud Alcohol. 1994a;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Cadoret RJ, Cloninger RC, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock V, Nurnberger JI, Reich T, Schmidt I, Schuckit MA. A New, Semi-Structured Psychiatric Interview For Use In Genetic Linkage Studies. J.Stud.Alcohol. 1994b;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creemers HE, Dijkstra JK, Vollebergh WA, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, Huizink AC. Predicting life-time and regular cannabis use during adolescence; the roles of temperament and peer substance use: the TRAILS study. Addiction. 2010;105:699–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creemers HE, Korhonen T, Kaprio J, Vollebergh WA, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, Huizink AC. The role of temperament in the relationship between early onset of tobacco and cannabis use: the TRAILS study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Chiu WT, Sampson N, Kessler RC, Anthony JC, Angermeyer M, Bruffaerts R, de GG, Gureje O, Huang Y, Karam A, Kostyuchenko S, Lepine JP, Mora ME, Neumark Y, Ormel JH, Pinto-Meza A, Posada-Villa J, Stein DJ, Takeshima T, Wells JE. Toward a global view of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine use: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys 1. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Swift W, Moore E, Patton GC. Outcomes of occasional cannabis use in adolescence: 10-year follow-up study in Victoria, Australia. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196:290–295. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.056952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deKort M. The Dutch cannabis debate. Journal of Drug Issues. 1994:417–418. [Google Scholar]

- Duhig AM, Cavallo DA, McKee SA, George TP, Krishnan-Sarin S. Daily patterns of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use in adolescent smokers and nonsmokers. Addict Behav. 2005;30:271–283. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan AE, Sartor CE, Scherrer JF, Grant JD, Heath AC, Nelson EC, Jacob T, Bucholz KK. The association between cannabis abuse and dependence and childhood physical and sexual abuse: evidence from an offspring of twins design. Addiction. 2008;103:990–997. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen S, True W, Goldberg J, Henderson W, Robinette CD. The Vietnam Era Twin (VET) Registry: method of construction. Acta Genet Med Gemellol (Roma) 1987;36:61–66. doi: 10.1017/s0001566000004591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ, Saner H. Antecedents and outcomes of marijuana use initiation during adolescence. Prev Med. 2004;39:976–984. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg J, True W, Eisen S, Henderson W, Robinette CD. The Vietnam Era Twin (VET) Registry: ascertainment bias. Acta Genet Med Gemellol (Roma) 1987;36:67–78. doi: 10.1017/s0001566000004608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JD, Lynskey MT, Scherrer JF, Agrawal A, Heath AC, Bucholz KK. A cotwin-control analysis of drug use and abuse/dependence risk associated with early-onset cannabis use. Addict Behav. 2010;35:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Hill KG, Guo J, Battin-Pearson SR. Substance Use Norms and Transitions in Substance Use: Implications for the Gateway Hypothesis. In: Kandel D, editor. Stages and Pathways of Drug Involvement. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 2002. pp. 42–64. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson WG, Eisen S, Goldberg J, True WR, Barnes JE, Vitek ME. The Vietnam Era Twin Registry: a resource for medical research. Public Health Rep. 1990;105:368–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofler M, Lieb R, Perkonigg A, Schuster P, Sonntag H, Wittchen HU. Covariates of cannabis use progression in a representative population sample of adolescents: a prospective examination of vulnerability and risk factors. Addiction. 1999;94:1679–1694. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.941116796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizink AC, Levalahti E, Korhonen T, Dick DM, Pulkkinen L, Rose RJ, Kaprio J. Tobacco, cannabis, and other illicit drug use among finnish adolescent twins: causal relationship or correlated liabilities? J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:5–14. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Waterman B, Heath A, True W, Bucholz KK, Haber R, Scherrer J, Fu Q. Genetic and environmental effects on offspring alcoholism: new insights using an offspring-of-twins design. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1265–1272. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.12.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D. Stages in adolescent involvement in drug use. Science. 1975;190:912–914. doi: 10.1126/science.1188374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D. Stages and Pathways of Drug Involvement. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D, Yamaguchi K. From beer to crack: developmental patterns of drug involvement. Am.J.Public Health. 1993;83:851–855. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.6.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Does marijuana use cause the use of other drugs? JAMA. 2003;289:482–483. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BC. Bongs and blunts: notes from a suburban marijuana subculture 1. J Ethn.Subst Abuse. 2005;4:81–97. doi: 10.1300/J233v04n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen T, Huizink AC, Dick DM, Pulkkinen L, Rose RJ, Kaprio J. Role of individual, peer and family factors in the use of cannabis and other illicit drugs: a longitudinal analysis among Finnish adolescent twins. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008b;97:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen T, Huizink AC, Dick DM, Pulkkinen L, Rose RJ, Kaprio J. Role of individual, peer and family factors in the use of cannabis and other illicit drugs: a longitudinal analysis among Finnish adolescent twins. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008a;97:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen T, van Leeuwen AP, Reijneveld SA, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, Huizink AC. Externalizing behavior problems and cigarette smoking as predictors of cannabis use: the TRAILS Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:61–69. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201001000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessem JM, Hopfer CJ, Haberstick BC, Timberlake D, Ehringer MA, Smolen A, Hewitt JK. Behav Genet. 2006. Relationship between Adolescent Marijuana Use and Young Adult Illicit Drug Use. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Brown RA. Level of current and past adolescent cigarette smoking as predictors of future substance use disorders in young adulthood. Addiction. 1999;94:913–921. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94691313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey M, Vink JM, Boomsma DI. Early onset cannabis use and progression to other drug use in a sample of Dutch twins. Behav.Genet. 2006;36:195–200. doi: 10.1007/s10519-005-9023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, Slutske WS, Madden PA, Nelson EC, Statham DJ, Martin NG. Escalation of drug use in early-onset cannabis users vs co-twin controls. JAMA. 2003;289:427–433. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay J, Eriksen M, Shafey O. The Tobacco Atlas. Nyraid Editions Limited edn The American Cancer Society; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Harvey E, Maes HH, Sullivan PF, Kendler KS. Extensions to the modeling of initiation and progression: applications to substance use and abuse. Behav Genet. 2006;36:507–524. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Sawyer SM, Lynskey M. Reverse gateways? Frequent cannabis use as a predictor of tobacco initiation and nicotine dependence. Addiction. 2005;100:1518–1525. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Sawyer SM, Wakefield M. Teen smokers reach their mid twenties. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ream GL, Benoit E, Johnson BD, Dunlap E. Smoking tobacco along with marijuana increases symptoms of cannabis dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;95:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Cottler LB, Goldring E. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Version III Revised Washington University; Saint Louis: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer JF, Waterman BM, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, True WR, Jacob T. Are substance use, abuse and dependence associated with study participation? Predictors of offspring nonparticipation in a twin-family study. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65:140–144. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suris JC, Akre C, Berchtold A, Jeannin A, Michaud PA. Some go without a cigarette: characteristics of cannabis users who have never smoked tobacco 1. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:1042–1047. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.11.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Vanyukov M, Kirisci L, Reynolds M, Clark DB. Predictors of marijuana use in adolescents before and after licit drug use: examination of the gateway hypothesis. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:2134–2140. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake DS. A comparison of drug use and dependence between blunt smokers and other cannabis users. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44:401–415. doi: 10.1080/10826080802347651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake DS, Haberstick BC, Hopfer CJ, Bricker J, Sakai JT, Lessem JM, Hewitt JK. Progression from marijuana use to daily smoking and nicotine dependence in a national sample of U.S. adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007a;88:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake DS, Haberstick BC, Hopfer CJ, Bricker J, Sakai JT, Lessem JM, Hewitt JK. Progression from marijuana use to daily smoking and nicotine dependence in a national sample of U.S. adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007b;88:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van GK, Rebellon CJ. A Life-course Perspective on the “Gateway Hypothesis”. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51:244–259. doi: 10.1177/0022146510378238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Frohlich C, Behrendt S, Gunther A, Rehm J, Zimmermann P, Lieb R, Perkonigg A. Cannabis use and cannabis use disorders and their relationship to mental disorders: a 10-year prospective-longitudinal community study in adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(Suppl 1):S60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.013. Epub@2007 Jan 25., S60-S70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]