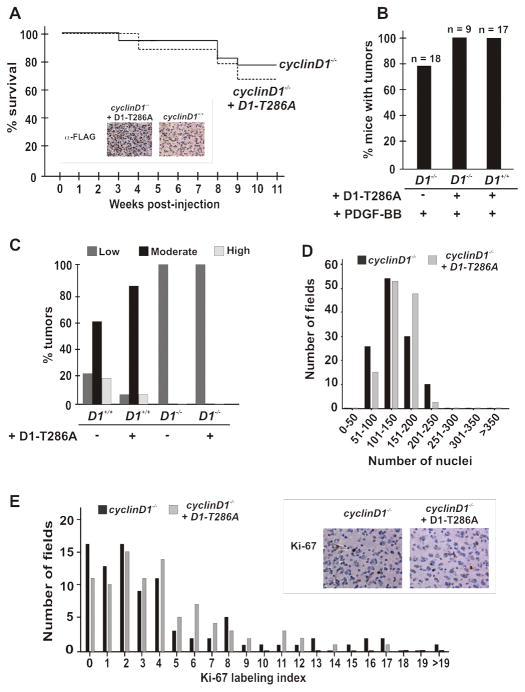

Figure 4. Expression of cyclin D1 in cyclin D1 knockout glial cells does not restore progression of PDGF-mediated gliomagenesis.

(A) Neonatal cyclin D1 knockout (n=9) nestin-tvA mice were injected intracranially with DF-1 chicken cells expressing RCAS-HA-PDGF or RCAS-cycD1-T286A, either singly or in combination. Mice were subsequently followed over the course of 11 weeks for the development of symptoms of gliomagenesis, at which time they were sacrificed. The original cyclinD1 knockout survival curve is depicted for comparison: cyclinD1−/− versus cyclinD1−/− + D1-T286A; log rank, p=0.41. Inset; Immunohistochemistry shows re-expression of the exogenous cyclinD1 allele in cyclinD1 knockout glial tumor cells following gene transfer of activated cyclinD1-T286A in cyclinD1 knockout animals. Tumors from wild type animals challenged with PDGF alone do not show reactivity. (B) Gross tumor formation was determined by H & E stain. (C) Exogenous cyclin D1 does not correct the histological grade of oligodendroglioma. (D) Re-expression of cyclin D1 does not affect tumor cellularity. The original plot for cyclin D1 knockout mice is shown for comparison. (E) Re-expression of cyclin D1 does not affect Ki-67 staining. The original cyclinD1 knockout data is plotted for comparison. cyclinD1−/− versus cyclinD1−/− + D1-T286A; log rank p = 0.93.