Abstract

Articles may be retracted when their findings are no longer considered trustworthy due to scientific misconduct or error, they plagiarize previously published work, or they are found to violate ethical guidelines. Using a novel measure that we call the “retraction index,” we found that the frequency of retraction varies among journals and shows a strong correlation with the journal impact factor. Although retractions are relatively rare, the retraction process is essential for correcting the literature and maintaining trust in the scientific process.

EDITORIAL

“A man who has committed a mistake, and doesn't correct it, is committing another mistake.”

—attributed to Confucius

Of more than 28,000 articles in its 40-year history, Infection and Immunity has issued only 15 retractions. Six of these were issued this year and arose from a single laboratory (52–55, 87, 89). This has prompted us to reflect on the process of manuscript retraction and its importance for science and to add to our essay series commenting on the descriptors and qualifiers of present-day science (13–16, 27, 28).

Reasons for retraction.

Eight of the articles retracted by Infection and Immunity, including the six most recent instances, were found to contain digital figures that had been inappropriately manipulated (51–55, 78, 87, 89). Six of the others were retracted by the authors after they determined their previously reported findings to be unreliable: two were unable to confirm their original results (42, 67), one discovered that a cDNA library was actually obtained from another organism (38), and three found a critical reagent to be impure (19, 49, 61). The remaining article was retracted due to extensive plagiarism (43). This is a reasonably representative sample of the reasons for manuscript retraction discussed in guidelines from the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (93, 94). A COPE survey of Medline retractions from 1988 to 2004 found 40% of retracted articles to be attributed to honest error or nonreplicable findings, 28% to research misconduct, 17% to redundant publication, and 15% to other or unstated reasons. Research misconduct is classified as falsification or fabrication, with falsification defined as the manipulation of materials, processes, or data to misrepresent results and fabrication defined as reporting the results of experiments that were not actually performed (57). Plagiarism refers to the misrepresentation of another's ideas or words as one's own and includes self-plagiarism, sometimes referred to as redundant publication. While some have criticized the term “self-plagiarism” on semantic grounds (7), it has nevertheless proven to be a useful way to describe the practices of publishing the same article in more than one journal or recycling large sections of text in more than one article.

Are retractions becoming more frequent?

Overall, manuscript retraction appears to be occurring more frequently, although it is uncertain whether this is a result of increasing misconduct or simply increasing detection due to enhanced vigilance. Steen reviewed 742 retracted articles and found that the number of retracted articles has risen approximately 10-fold over the past decade, with the greatest increase among those retracted due to misconduct (83). Although errors certainly account for the greatest proportion of retracted articles (56), Steen has argued that many retractions are a consequence of deliberate attempts by an author to deceive (84). Most scientists feel that research misconduct is uncommon. However, a meta-analysis of survey data reported that 2% of scientists report having committed serious research misconduct at least once, and one-third admit to having engaged in questionable research practices (26). Given the stigma associated with retractions and the challenges in detecting misconduct, it is likely that retractions represent only the tip of the iceberg (65). Last year, the journalists Ivan Oransky and Adam Marcus launched a blog called “Retraction Watch,” which is devoted to the examination of retracted articles “as a window into the scientific process” (60); sadly, they seem to have no trouble finding material.

ASM ethical guidelines and retraction policy.

A 2004 survey found that many scientific journals lack formal retraction policies (5). However, the journals of the American Society for Microbiology have specific guidelines for ethical conduct and retractions, which are detailed in the Instructions to Authors (3). These guidelines define plagiarism as well as the fabrication, manipulation, or falsification of data. In addition, the ASM guidelines distinguish between retractions, which are reserved for major errors or misconduct that call the conclusions of an article into question, and errata or authors' corrections, which rectify minor errors. The issue of manipulation of computer-generated images is specifically addressed, with image processing acceptable only if applied to all parts of an image. The interested reader is referred to an excellent commentary by the editors of the Journal of Cell Biology for an extensive discussion of inappropriate digital-image manipulation (68).

Although journals have an important role to play, they do not have primary responsibility for investigating possible scientific misconduct. That responsibility rests with the author's institution (79, 82) and, if funding from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is involved, the Office of Research Integrity. Nevertheless, if an editor has concerns about the validity of data in a submitted manuscript, the editor has the prerogative to request that authors provide their raw data for review. If misconduct is suspected, the journal should contact the institution and recommend an inquiry. Once an institution has determined that misconduct involving research publications has occurred, journals are obligated to consider retraction of the work. In the case involving repeated instances of digital-figure manipulation that resulted in six retracted Infection and Immunity articles earlier this year, another journal initially raised the question of misconduct, and the author's institution performed a thorough investigation before informing Infection and Immunity of its concerns. After receiving this notification, Infection and Immunity performed an independent review of the evidence, requested a response from the author(s), and then reached a decision to retract the articles in question after consultation with multiple editors and members of the ASM Publications Board.

Either publishers or authors may initiate a retraction (50, 93). Retraction notices are posted in PubMed and available free of charge, and the pdf versions of retracted articles now carry a watermark to inform readers that the article has been retracted. Authors are consulted regarding the wording of a retraction, but final decisions are at the discretion of the journal. Some journals appear to give authors considerable latitude in wording a retraction notice (23), but this is probably inadvisable (81). The bloggers at Retraction Watch have advocated transparency in retraction notices (59). We concur with the COPE guidelines that notices should state who is issuing the retraction and the reason for the retraction in order to distinguish misconduct from error. The goal in writing a retraction notice is to be clear, accurate, and fair, with fairness applying to both the authors and journal readership. However, beyond this basic information, we are reminded of William Galston's observation that some things must be shrouded “for the same reason that middle-aged people should be clothed” (10).

As a reader once commented to us, “there is no statute of limitation on retractions.” In 1955, Homer Jacobson published an article called “Information, Reproduction and the Origin of Life” in the journal American Scientist (41). Fifty-two years later, after learning that creationists were citing his article as evidence for the divine origin of life, he decided to retract the article (20). Similarly, in 1920 the New York Times published an editorial mocking the aerospace pioneer Robert Goddard for suggesting that a rocket could function in the vacuum of space, stating that Goddard “seems to lack the knowledge ladled out daily in high schools.” The newspaper later retracted their article on 17 July 1969, following the successful launch of Apollo 11 (58).

Can retracted articles be republished?

In theory, a retracted article may be revised and republished, with removal of any erroneous, falsified, fabricated, or plagiarized content. In practice, however, authors of a retracted article may find republication to be a challenge. If misconduct has taken place, the authors may be subject to sanctions from the journal, which prohibit resubmission within a specified time frame. Misconduct compromises the trust between author and editor, and in such cases, authors may find it awkward to later approach the same journal to request consideration of a previously retracted article. In addition, the passage of time may have reduced the significance of the reported findings such that the article is no longer assigned high priority by the journal. Nevertheless, there are instances in which a retracted article has been corrected and republished by the same or another journal (17, 30, 43, 44, 46, 47). Scientists, it would seem, also believe in redemption.

Journals differ in retraction frequency.

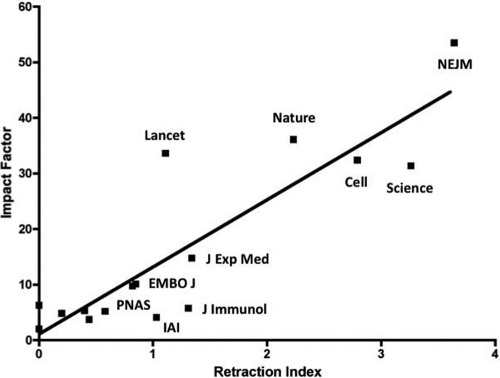

To determine whether journals differ in frequency of retracted articles and whether there is a relationship between retraction frequency and journal impact factor, we carried out a PubMed search for retracted articles among 17 journals ranging in impact factor between 2.00 to 53.484. We defined a “retraction index” for each journal as the number of retractions in the time interval from 2001 to 2010, multiplied by 1,000, and divided by the number of published articles with abstracts. A plot of the journal retraction index versus the impact factor revealed a surprisingly robust correlation between the journal retraction index and its impact factor (P < 0.0001 by Spearman rank correlation) (Fig. 1). Although correlation does not imply causality, this preliminary investigation suggests that the probability that an article published in a higher-impact journal will be retracted is higher than that for an article published in a lower-impact journal.

Fig. 1.

Correlation between impact factor and retraction index. The 2010 journal impact factor (37) is plotted against the retraction index as a measure of the frequency of retracted articles from 2001 to 2010 (see text for details). Journals analyzed were Cell, EMBO Journal, FEMS Microbiology Letters, Infection and Immunity, Journal of Bacteriology, Journal of Biological Chemistry, Journal of Experimental Medicine, Journal of Immunology, Journal of Infectious Diseases, Journal of Virology, Lancet, Microbial Pathogenesis, Molecular Microbiology, Nature, New England Journal of Medicine, PNAS, and Science.

The correlation between a journal's retraction index and its impact factor suggests that there may be systemic aspects of the scientific publication process that can affect the likelihood of retraction. When considering various explanations, it is important to note that the economics and sociology of the current scientific enterprise dictate that publication in high-impact journals can confer a disproportionate benefit to authors relative to publication of the same material in a journal with a lower impact factor. For example, publication in journals with high impact factors can be associated with improved job opportunities, grant success, peer recognition, and honorific rewards, despite widespread acknowledgment that impact factor is a flawed measure of scientific quality and importance (8, 29, 33, 77, 80, 86). Hence, one possibility is that fraud and scientific misconduct are higher in papers submitted and accepted to higher-impact journals. In this regard, the disproportionally high payoff associated with publishing in higher-impact journals could encourage risk-taking behavior by authors in study design, data presentation, data analysis, and interpretation that subsequently leads to the retraction of the work. Another possibility is that the desire of high-impact journals for clear and definitive reports may encourage authors to manipulate their data to meet this expectation. In contradistinction to the crisp, orderly results of a typical manuscript in a high-impact journal, the reality of everyday science is often a messy affair littered with nonreproducible experiments, outlier data points, unexplained results, and observations that fail to fit into a neat story. In such situations, desperate authors may be enticed to take short cuts, withhold data from the review process, overinterpret results, manipulate images, and engage in behavior ranging from questionable practices to outright fraud (26). Alternatively, publications in high-impact journals have increased visibility and may accordingly attract greater scrutiny that results in the discovery of problems eventually leading to retraction. It is possible that each of these explanations contributes to the correlation between retraction index and impact factor. Whatever the explanation, the phenomenon appears deserving of further study. The relationship between retraction index and impact factor is yet another reason to be wary of simple bibliometric measures of scientific performance, such as impact factor.

Impact of research misconduct.

Science must try to be self-correcting, and retractions provide a critically important function by rectifying the scientific record. However, the system is far from perfect. As we have already noted, it is likely that only a small percentage of scientific misconduct results in retraction. Sensational new claims attract scrutiny and are more likely to be refuted by subsequent research (2, 34, 35, 64, 69–76, 95). However, reports based on falsified or fabricated data may be more difficult to detect if the conclusions happen to be true. Retractions often do not occur for years after publication (1, 18, 21, 90), which is perhaps understandable given the time required for other researchers to attempt to replicate results and for institutions to perform thorough investigations (100), but this means that erroneous information remains in circulation for prolonged periods before correction (62). Moreover, it is disheartening that retracted articles continue to be cited, sometimes for decades afterward (11, 24, 45, 63, 66, 88, 96).

It is not difficult to surmise the underlying causes of research misconduct. Misconduct represents the dark side of the hypercompetitive environment of contemporary science, with its emphasis on funding, numbers of publications, and impact factor (39). With such potent incentives for cheating, it is not surprising that some scientists succumb to temptation. As Eric Poehlman, an obesity researcher sentenced to jail for research misconduct, said at his sentencing hearing, “I had placed myself…in an academic position in which the amount of grants that you held basically determined one's self worth…everything flowed from that” (36). Funding agencies and journals provide regulations and disincentives for misconduct, but these may be inadequate if the incentives are too great and even counterproductive if the penalties are excessively harsh. Another response to misconduct has been to increase formal ethics instruction for research trainees. While this effort may be worthwhile, there is little evidence of its effectiveness (31). When a prominent article is retracted, a common refrain is, “Why didn't the reviewers catch that?” In fact, many would-be retractions are caught during the review process. However, without access to raw data, it is unrealistic to expect that even careful and highly motivated reviewers can detect all instances of falsification or fabrication.

Plagiarism is a more complex matter, as it is based upon a modern concept of intellectual property that dates back only to 18th-century Europe (12). The rise of the internet has facilitated plagiarism, but technology has also arisen to facilitate the detection of plagiarism or redundant publication (25, 32, 48, 92). Some have suggested that plagiarism is a culturally relative concept, which is less likely to be regarded as an unethical practice by some scientists in non-Western countries or those belonging to the younger generation (9, 22, 40, 91, 97–99). However, we do not share this view. Scientists must be explorers, and it is best if they do not precisely follow the wagon ruts left by their predecessors but instead strike out on their own paths, using their own words. The ASM journals strictly prohibit plagiarism and self-plagiarism.

Conclusions.

The increasing rate of retracted scientific articles is a disturbing trend. Although correction of the scientific record is laudable per se, erroneous or fraudulent research can cause enormous harm, diverting other scientists to unproductive lines of investigation, leading to the unfair distribution of scientific resources, and in the worst cases, even resulting in inappropriate medical treatment of patients (6, 85). Furthermore, retractions can erode public confidence in science. Any retraction represents a tremendous waste of scientific resources that are often supported with public funding, and the retraction of published work can undermine the faith of the public in science and their willingness to provide continued support. The corrosive impact of retracted science is disproportionate to the relatively small number of retracted articles. The scientific process is heavily dependent on trust. To the extent that misconduct erodes scientists' confidence in the literature and in each other, it seriously damages science itself. As Arst has noted, “All honest scientists are victims of scientists who commit misconduct” (4). Yet, retractions also have tremendous value. They signify that science corrects its mistakes.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

It has recently been brought to our attention that previous independent analyses have also concluded that articles in journals with higher impact factors are more likely to be retracted (Liu, S. V. Top journals' top retraction rates. Sci. Ethics 1:91–93, 2006; Cokol, M., I. lossifov, R. Rodriguez-Esteban, and A. Rzhetsky. How many scientific papers should be retracted? EMBO Rep. 8:422–423, 2007).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 August 2011.

The views expressed in this Editorial do not necessarily reflect the views of the journal or of ASM.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abbott A., Schwarz J. 2002. Dubious data remain in print two years after misconduct inquiry. Nature 418:113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ahluwalia J., et al. 2004. The large-conductance Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channel is essential for innate immunity. Nature 427:853–858 (Retraction, 468:122, 2010.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 3. American Society for Microbiology December 2010, posting date. IAI instructions to authors. http://iai.asm.org/misc/ifora.dtl

- 4. Arst H. N. J. 2000. Apathy rewards misconduct—and everybody suffers. Nature 403:478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Atlas M. C. 2004. Retraction policies of high-impact biomedical journals. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 92:242–250 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Avery S. 9 January 2011. Flawed research appalls cancer patient. News & Observer, Raleigh, NC [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bird S. J. 2002. Self-plagiarism and dual and redundant publications: what is the problem? Commentary on ‘Seven ways to plagiarize: handling real allegations of research misconduct.’ Sci. Eng. Ethics 8:543–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bloch S., Walter G. 2001. The impact factor: time for change. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 35:563–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brentlinger P. E., et al. 2009. Plagiarism. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 103:855 (Author reply, 855-856.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brooks D., Collins G. 27 January 2010. What Obama should say tonight. New York Times, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 11. Budd J. M., Sievert M., Schultz T. R. 1998. Phenomena of retraction: reasons for retraction and citations to the publications. JAMA 280:296–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buranen L., Roy A. M. (ed.). 1999. Perspectives on plagiarism and intellectual property in a postmodern world. SUNY Press, Albany, NY [Google Scholar]

- 13. Casadevall A., Fang F. C. 2008. Descriptive science. Infect. Immun. 76:3835–3836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Casadevall A., Fang F. C. 2009. Important science—it's all about the SPIN. Infect. Immun. 77:4177–4180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Casadevall A., Fang F. C. 2009. Mechanistic science. Infect. Immun. 77:3517–3519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Casadevall A., Fang F. C. 2010. Reproducible science. Infect. Immun. 78:4972–4975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cittadini E., Goadsby P. J. 2005. Psychiatric side effects during methysergide treatment. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 76:1037–1038 (Retraction, 77:426, 2006; retracted article reinstated, 81:942, 2010.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Couzin J., Unger K. 2006. Scientific misconduct. Cleaning up the paper trail. Science 312:38–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cue D. R., Cleary P. P. 1997. High-frequency invasion of epithelial cells by Streptococcus pyogenes can be activated by fibrinogen and peptides containing the sequence RGD. Infect. Immun. 65:2759–2764 (Retraction, 66:4577, 1998.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 20. Dean C. 25 October 2007. '55 ‘origin of life’ paper is retracted. New York Times, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 21. DeCoursey T. E. 2006. It's difficult to publish contradictory findings. Nature 439:784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Derby B. 2008. Duplication and plagiarism increasing among students. Nature 452:29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ding K. 2009. Letter of rebuttal and apology to editor on the retraction of “Velocity of polymer translocation through a pore.” Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 389:684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Drury N. E., Karamanou D. M. 2009. Citation of retracted articles: a call for vigilance. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 87(2):670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Errami M., Garner H. 2008. A tale of two citations. Nature 451:397–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fanelli D. 2009. How many scientists fabricate and falsify research? A systematic review and meta-analysis of survey data. PLoS One 4:e5738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fang F. C., Casadevall A. 2010. Lost in translation—basic science in the era of translational research. Infect. Immun. 78:563–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fang F. C., Casadevall A. 2011. Reductionistic and holistic science. Infect. Immun. 79:1401–1404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fersht A. 2009. The most influential journals: impact factor and Eigenfactor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:6883–6884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fontanarosa P. B., DeAngelis C. D. 2005. Correcting the literature—retraction and republication. JAMA 293:2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Funk C. L., Barrett K. A., Macrina F. L. 2007. Authorship and publication practices: evaluation of the effect of responsible conduct of research instruction to postdoctoral trainees. Account. Res. 14:269–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Giles J. 2005. Taking on the cheats. Nature 435:258–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hansson S. 1995. Impact factor as a misleading tool in evaluation of medical journals. Lancet 346(8979):906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hwang W. S., et al. 2004. Evidence of a pluripotent human embryonic stem cell line derived from a cloned blastocyst. Science 303:1669–1674(Retraction, 311:335, 2006.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hwang W. S., et al. 2005. Patient-specific embryonic stem cells derived from human SCNT blastocysts. Science 308:1777–1783(Retraction, 311:335, 2006.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Interlandi J. 22 October 2006. An unwelcome discovery. New York Times, New York, NY: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. ISI 2011. ISI journal citation reports 2010. Thomson Reuters, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ismail S. O., Skeiky Y. A., Bhatia A., Omara-Opyene L. A., Gedamu L. 1994. Molecular cloning, characterization, and expression in Escherichia coli of iron superoxide dismutase cDNA from Leishmania donovani chagasi. Infect. Immun. 62:657–664(Retraction, 63:3749, 1995.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 39. Iyengar R., Wang Y., Chow J., Charney D. S. 2009. An integrated approach to evaluate faculty members' research performance. Acad. Med. 84:1610–1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jackson A. C., Ronald A. R., Steiner I. 2010. Plagiarism. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 104:173(Discussion, 173–174.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jacobson H. 1955. Information, reproduction and the origin of life. Am. Sci. 43:125 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kalia A., Enright M. C., Spratt B. G., Bessen D. E. 2001. Directional gene movement from human-pathogenic to commensal-like streptococci. Infect. Immun. 69:4858–4869(Retraction, 77:4688, 2009.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 43. Khatua B., et al. 22 December 2008. Sialic acids, important constituents and selective recognition factors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an opportunistic pathogen. Infect. Immun. [Epub ahead of print.] doi:10.1128/IAI.01083-08. (Retracted 29 January 2009.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Khatua B., et al. 2010. Sialic acids acquired by Pseudomonas aeruginosa are involved in reduced complement deposition and siglec mediated host-cell recognition. FEBS Lett. 584:555–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Korpela K. M. 2010. How long does it take for the scientific literature to purge itself of fraudulent material?: the Breuning case revisited. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 26:843–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Levin L. I., et al. 2005. Temporal relationship between elevation of Epstein-Barr virus antibody titers and initial onset of neurological symptoms in multiple sclerosis. JAMA 293:2496–2500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Levin L. I., et al. 2003. Multiple sclerosis and Epstein-Barr virus. JAMA 289:1533–1536(Retraction, 293:2466, 2005.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Long T. C., Errami M., George A. C., Sun Z., Garner H. R. 2009. Scientific integrity. Responding to possible plagiarism. Science 323:1293–1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Marcato P., Mulvey G., Armstrong G. D. 2002. Cloned Shiga toxin 2 B subunit induces apoptosis in Ramos Burkitt's lymphoma B cells. Infect. Immun. 70:1279–1286 (Retraction, 71:4828, 2003.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 50. Marcus E. 2005. Retraction controversy. Cell 123:173–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McNally A., et al. 2001. Differences in levels of secreted locus of enterocyte effacement proteins between human disease-associated and bovine Escherichia coli O157. Infect. Immun. 69:5107–5114 (Retraction, 73:2571, 2005.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 52. Mori N., et al. 1999. Essential role of transcription factor nuclear factor-kappaB in regulation of interleukin-8 gene expression by nitrite reductase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in respiratory epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 67:3872–3878(Retraction, 79:3473, 2011.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 53. Mori N., et al. 2000. Activation of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 expression by Helicobacter pylori is regulated by NF-kappaB in gastric epithelial cancer cells. Infect. Immun. 68:1806–1814(Retraction, 79:542, 2011.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 54. Mori N., et al. 2003. Helicobacter pylori induces RANTES through activation of NF-kappaB. Infect. Immun. 71:3748–3756(Retraction, 79:544, 2011.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 55. Mori N., et al. 2001. Induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 by Helicobacter pylori involves NF-kappaB. Infect. Immun. 69:1280–1286(Retraction, 79:543, 2011.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 56. Nath S. B., Marcus S. C., Druss B. G. 2006. Retractions in the research literature: misconduct or mistakes? Med. J. Aust. 185:152–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. National Science Foundation 2002. Research misconduct, 45 C.F.R. part 689.1. National Science Foundation, Arlington, VA [Google Scholar]

- 58. New York Times 13 January 1920. Topics of the Times. New York Times, New York, NY: (Correction, 17 July 1969.) [Google Scholar]

- 59. Oransky I. 2011. Retraction watch. As last of 12 promised Bulfone-Paus retractions appears, a (disappointing) report card on journal transparency. http://retractionwatch.wordpress.com/2011/03/14/as-last-of-12-promised-bulfone-paus-retractions-appears-a-disappointing-report-card-on-journal-transparency/

- 60. Oransky I., Marcus A. 3 August 2010, launch date. Retraction watch. http://retractionwatch.wordpress.com [Google Scholar]

- 61. Orme I. M., et al. 1993. Inhibition of growth of Mycobacterium avium in murine and human mononuclear phagocytes by migration inhibitory factor. Infect. Immun. 61:338–342 (Retraction, 62:2141, 1994.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 62. Parrish D. M. 1999. Scientific misconduct and correcting the scientific literature. Acad. Med. 74:221–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Peterson G. M. 2010. The effectiveness of the practice of correction and republication in the biomedical literature. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 98:135–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Potti A., et al. 2006. A genomic strategy to refine prognosis in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer N. Engl. J. Med. 355:570–580 (Retraction, 364:1176, 2011.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Poulton A. 2007. Mistakes and misconduct in the research literature: retractions just the tip of the iceberg. Med. J. Aust. 186:323–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Redman B. K., Yarandi H. N., Merz J. F. 2008. Empirical developments in retraction. J. Med. Ethics 34:807–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Reynaud A., Federighi M., Licois D., Guillot J. F., Joly B. 1991. R plasmid in Escherichia coli O103 coding for colonization of the rabbit intestinal tract. Infect. Immun. 59:1888–1892 (Retraction, 61:4533, 1993.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 68. Rossner M., Yamada K. M. 2004. What's in a picture? The temptation of image manipulation. J. Cell Biol. 166:11–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Schon J. H., Meng H., Bao Z. 2001. Field-effect modulation of the conductance of single molecules. Science 294:2138–2140(Retraction, 298:961, 2002.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Schon J. H., Kloc C., Haddon R. C., Batlogg B. 2000. A superconducting field-effect switch. Science 288:656–658(Retraction, 298:961, 2002.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Schon J. H., Kloc C., Batlogg B. 2000. Fractional quantum hall effect in organic molecular semiconductors. Science 288:2339–2340(Retraction, 298:961, 2002.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Schon J. H., Kloc C., Dodabalapur A., Batlogg B. 2000. An organic solid state injection laser. Science 289:599–601(Retraction, 298:961, 2002.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Schon J. H., Berg S., Kloc C., Batlogg B. 2000. Ambipolar pentacene field-effect transistors and inverters. Science 287:1022–1023(Retraction, 298:961, 2002.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Schon J. H., Kloc C., Batlogg B. 2001. High-temperature superconductivity in lattice-expanded C60. Science 293:2432–2434(Retraction, 298:961, 2002.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Schon J. H., Dodabalapur A., Kloc C., Batlogg B. 2000. A light-emitting field-effect transistor. Science 290:963–966(Retraction, 298:961, 2002.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Schon J. H., Kloc C., Hwang H. Y., Batlogg B. 2001. Josephson junctions with tunable weak links. Science 292:252–254(Retraction, 298:961, 2002.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Seglen P. O. 1997. Why the impact factor of journals should not be used for evaluating research. BMJ 314:498–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Shin J. J., Bryksin A. V., Godfrey H. P., Cabello F. C. 2004. Localization of BmpA on the exposed outer membrane of Borrelia burgdorferi by monospecific anti-recombinant BmpA rabbit antibodies. Infect. Immun. 72:2280–2287(Retraction, 76:4792, 2008.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 79. Smith R. 2005. Investigating the previous studies of a fraudulent author. BMJ 331:288–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Smith R. 2008. Beware the tyranny of impact factors. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 90:125–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Souder L. 2010. A rhetorical analysis of apologies for scientific misconduct: do they really mean it? Sci. Eng. Ethics 16:175–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sox H. C., Rennie D. 2006. Research misconduct, retraction, and cleansing the medical literature: lessons from the Poehlman case. Ann. Intern. Med. 144:609–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Steen R. G. 2011. Retractions in the scientific literature: is the incidence of research fraud increasing? J. Med. Ethics 37:249–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Steen R. G. Misinformation in the medical literature: what role do error and fraud play? J. Med. Ethics. 2011 Feb 22; doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.041830. [Epub ahead of print.] doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.041830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Steen R. G. Retractions in the medical literature: how many patients are put at risk by flawed research? J. Med. Ethics. 2011 May 17; doi: 10.1136/jme.2011.043133. [Epub ahead of print.] doi: 10.1136/jme.2011.043133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Szklo M. 2008. Impact factor: good reasons for concern. Epidemiology 19:369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Takeshima E., et al. 2009. Helicobacter pylori-induced interleukin-12 p40 expression. Infect. Immun. 77:1337–1348(Retraction, 79:546, 2011.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 88. Tatsioni A., Bonitsis N. G., Ioannidis J. P. 2007. Persistence of contradicted claims in the literature. JAMA 298:2517–2526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Tomimori K., et al. 2007. Helicobacter pylori induces CCL20 expression. Infect. Immun. 75:5223–5232(Retraction, 79:545, 2011.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 90. Trikalinos N. A., Evangelou E., Ioannidis J. P. 2008. Falsified papers in high-impact journals were slow to retract and indistinguishable from nonfraudulent papers. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 61:464–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Vessal K., Habibzadeh F. 2007. Rules of the game of scientific writing: fair play and plagiarism. Lancet 369(9562):641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Vihinen M. 2009. Problems with anti-plagiarism database. Nature 457:26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Wager E., Barbour V., Yentis S., Kleinert S. 2010. Retractions: guidance from the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). Obes. Rev. 11:64–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Wager E., Williams P. 12 April 2011. Why and how do journals retract articles? An analysis of Medline retractions 1988-2008. J. Med. Ethics [Epub ahead of print.] doi:10.1136/jme.2010.040964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Wakefield A. J., et al. 1998. Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet 351:637–641(Retraction, 375:445, 2010.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Whitely W. P., Rennie D., Hafner A. W. 1994. The scientific community's response to evidence of fraudulent publication. The Robert Slutsky case. JAMA 272:170–173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Wicker P. 2007. Plagiarism: understanding and management. J. Perioper. Pract. 17:372, 377–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Yilmaz I. 2007. Plagiarism? No, we're just borrowing better English. Nature 449:658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Zhang Y. 2010. Chinese journal finds 31% of submissions plagiarized. Nature 467:153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Zimmer C. 2011. It's science, but not necessarily right. New York Times opinion. New York Times, New York, NY [Google Scholar]