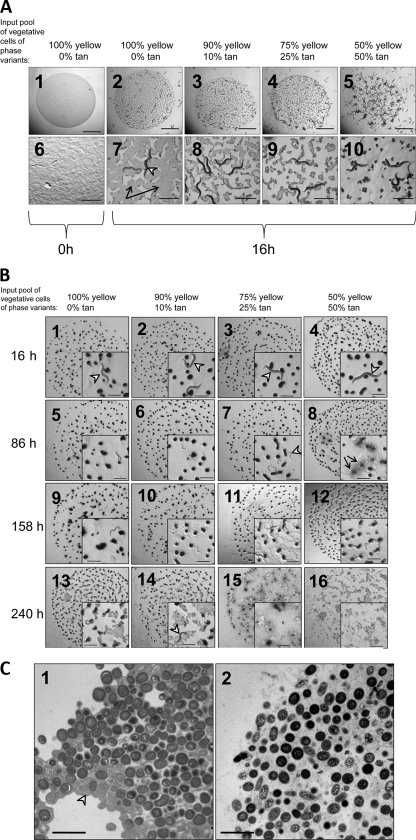

Fig. 4.

C. elegans worms preferentially digest tan fruiting body spores. (A) Fruiting bodies from TPM starvation plates were harvested and then sonicated (setting 1.5) to dispersed spores into homogeneous solutions that were spotted onto agar plates in 20-μl aliquots (panels 1 and 6). Bars, 5 mm for panel 1 and 1 mm for panel 6. The same number of C. elegans worms was added to each mixture of fruiting body spores and allowed to feed for 16 h (panels 2 to 5 and 7 to 10). In panel 7, the arrows indicate the still existing lawn of spores and the arrowhead indicates a C. elegans L4 larva/adult feeding on bacteria. Bars, 5 mm for panels 2 to 5 and 1 mm for panels 7 to 10. (B) Fruiting bodies were allowed to form from various mixtures of phase variants on TPM starvation agar containing cholesterol and CaCl2 to support nematode replication. After 5 days of starvation-induced sporulation, intact and attached fruiting bodies were subjected to feeding by C. elegans. Appearances of fruiting bodies present in 20-μl aliquots were recorded after 16, 86, 158, and 240 h of nematode feeding. The more fruiting bodies were composed of tan variants, the more susceptible the fruiting bodies were to disruption by C. elegans (Fig. 4B, compare panel 16 inset with panel 13 to 15 insets). (C) TEM (magnification, ×30,000) analysis of a 5-day-old fruiting body from an input population of 100% yellow cells (panel 1) or 50% yellow and 50% tan cells (panel 2). The greater number of yellow cells corresponds to a greater electron-dense ECM packaging spores together (panel 1, arrowhead). Bars, 5 μm.