Abstract

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are fundamental components of the plant innate immune system. MPK3 and MPK6 are Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) MAPKs activated by pathogens and elicitors such as oligogalacturonides (OGs), which function as damage-associated molecular patterns, and flg22, a well-known microbe-associated molecular pattern. However, the specific contribution of MPK3 and MPK6 to the regulation of elicitor-induced defense responses is not completely defined. In this work we have investigated the roles played by these MAPKs in elicitor-induced resistance against the fungal pathogen Botrytis cinerea. Analysis of single mapk mutants revealed that lack of MPK3 increases basal susceptibility to the fungus, as previously reported, but does not significantly affect elicitor-induced resistance. Instead, lack of MPK6 has no effect on basal resistance but suppresses OG- and flg22-induced resistance to B. cinerea. Overexpression of the AP2C1 phosphatase leads to impaired OG- and flg22-induced phosphorylation of both MPK3 and MPK6, and to phenotypes that recapitulate those of the single mapk mutants. These data indicate that OG- and flg22-induced defense responses effective against B. cinerea are mainly dependent on MAPKs, with a greater contribution of MPK6.

Plants are constantly exposed to potential pathogenic microorganisms, and a prompt recognition of attempted attacks is necessary to mount effective defense responses and restrict infection. In particular, detection of different microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), which are molecules conserved in a wide range of microbial organisms, is essential to trigger immunity against bacteria and fungi (Schwessinger and Zipfel, 2008). A well-known case of MAMP recognition is the perception of the 22-amino acid peptide flg22, present in bacterial flagellin, by the receptor kinase FLS2 (Gómez-Gómez and Boller, 2000). Besides MAMPs, plant cells are able to recognize endogenous molecules that are generated during pathogen infection or mechanical damage (damage-associated molecular patterns [DAMPs]). Well-characterized DAMPs are the oligogalacturonides (OGs), pectin fragments released from the plant cell wall by fungal polygalacturonases (Hahn et al., 1981; Ridley et al., 2001). The accumulation of active OGs, with a degree of polymerization between 10 and 15, is favored by the presence of polygalacturonase-inhibiting proteins in the apoplast (De Lorenzo and Ferrari, 2002; Casasoli et al., 2009). OGs elicit a variety of responses, including the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS; Bellincampi et al., 2000; Galletti et al., 2008), a rapid modification of membrane polarization and ion fluxes (Mathieu et al., 1991; Thain et al., 1995), the induction of defense-related genes, and the accumulation of phytoalexins (Davis et al., 1986). Activation of defense responses by OGs increases resistance of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and grape (Vitis vinifera) leaves against the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea (Aziz et al., 2004; Ferrari et al., 2007). Recently, the wall-associated kinase WAK1 has been identified as a receptor of OGs (Brutus et al., 2010; De Lorenzo et al., 2011).

Early responses induced by DAMPs and MAMPs largely overlap (Denoux et al., 2008). One of the earliest events occurring upon DAMP or MAMP perception is the phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs). MAPK cascades are used by all eukaryotes to convey signals generated from the perception of both extra- and intracellular stimuli, and generally involve three kinds of protein kinases: upstream MAP triple kinases (MAPKKKs), intermediate MAPK kinases (MAPKKs), and MAPKs. Plant MAPKs show the highest homology to the extracellular signal-regulated kinase subfamily of animal MAPKs (Ligterink and Hirt, 2001), whose activity is tightly controlled by dual phosphorylation of a TXY motif in the activation loop (Jonak et al., 2002). Once phosphorylated, a MAPK may activate cellular responses by phosphorylating transcription factors, either directly or via downstream effector proteins (Andreasson et al., 2005; Menke et al., 2005; Djamei et al., 2007; Qiu et al., 2008; Yoo et al., 2008; Bethke et al., 2009; Ishihama et al., 2011; Mao et al., 2011).

In Arabidopsis, three MAPKs (MPK3, MPK4, and MPK6) have been implicated in defense against pathogens (Asai et al., 2002; Ichimura et al., 2006; Qiu et al., 2008). An early investigation, performed by using a protoplast transient expression system, identified a complete Arabidopsis MAPK cascade activated by flg22 and including the MAPKKK MEKK1, the functionally redundant MAPKKs MKK4 and MKK5, and MPK3 and MPK6. Activation of this cascade was shown to positively regulate the expression of several defense-related genes and to confer resistance to both bacterial and fungal pathogens (Asai et al., 2002). However, subsequent studies showed that MPK3 and MPK6 are activated by flg22 also in absence of a functional MEKK1, indicating that other MAPKKKs, besides MEKK1, are involved in the activation of these MAPKs (Ichimura et al., 2006; Nakagami et al., 2006; Suarez-Rodriguez et al., 2007).

More recently, a signaling module involving MEKK1, the MAPKKs MKK1 and MKK2, and MPK4 was shown to negatively, rather than positively, regulate salicylic acid (SA) and ROS production (Gao et al., 2008). Consistently, loss-of-function mpk4 mutants accumulate elevated levels of SA and ROS, constitutively express defense-related genes, and show increased resistance to pathogens (Petersen et al., 2000). In contrast to MPK4, increasing evidence indicates that MPK3 and MPK6 exert a positive role on the activation of Arabidopsis defense responses. For instance, they have been shown to regulate camalexin accumulation (Ren et al., 2008) and ethylene (ET) production during fungal infection, and to be required for chemically induced priming of stress responses (Beckers et al., 2009).

Although the involvement of MPK3, MPK4, and MPK6 in the activation of Arabidopsis defense responses is now evident, a clear picture of their specific contribution to DAMP- and MAMP-induced resistance against pathogens is still missing. In this work we have investigated the specific roles played by MPK3 and MPK6 in elicitor-induced resistance to B. cinerea. We show that MPK6 plays a fundamental role in elicitor-induced resistance, whereas it is dispensable for basal resistance to the fungus. On the other hand, lack of MPK3 increases basal susceptibility, as previously reported (Ren et al., 2008), but does not significantly affect elicitor-induced resistance. Consistently, simultaneous dephosphorylation of MPK3 and MPK6 in transgenic plants overexpressing the Arabidopsis MAPK Ser/Thr phosphatase AP2C1 (Schweighofer et al., 2007) impairs both basal and induced resistance to B. cinerea, recapitulating the phenotypes observed in single mapk mutants.

RESULTS

Contribution of MPK3 and MPK6 to Elicitor-Induced Resistance to B. cinerea

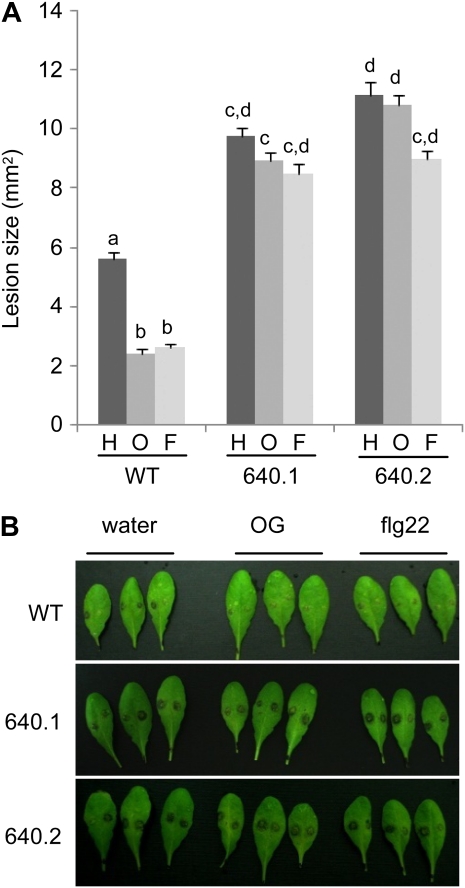

Pretreatment with OGs or flg22 protects Arabidopsis plants against B. cinerea infection (Ferrari et al., 2007), and this effect is independent of signaling pathways mediated by ET, jasmonate, and SA (Ferrari et al., 2007). To evaluate the specific contribution of MPK3 and MPK6 in elicitor-induced protection, we analyzed the response to B. cinerea upon pretreatment with OGs or flg22 in homozygous mpk3-1 and mpk6-2 single mutants, which lack detectable transcripts of MPK3 and MPK6, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Leaves from wild-type or mutant plants were infiltrated with OGs (100 μg mL−1), flg22 (10 nm, a nonsaturating dose that provides a degree of protection similar to that achieved with 100 μg mL−1 OGs), or water, and subsequently inoculated with the fungus. As a control, we included in the analysis the camalexin biosynthetic mutant pad3 (Zhou et al., 1999), which was previously shown to be impaired in both basal and induced resistance to B. cinerea (Ferrari et al., 2003, 2007). Basal resistance to B. cinerea was not affected in the mpk6-2 mutant, whereas it was decreased in the mpk3-1 mutant (Fig. 1), in agreement with what previously reported (Ren et al., 2008). As expected, elicitor-treated wild-type leaves developed smaller lesions with respect to leaves treated with water, whereas the pad3 mutant was significantly more susceptible to the fungus and was not protected by either OGs or flg22 (Fig. 1). Notably, resistance to B. cinerea induced by either OGs or flg22 was lost in mpk6-2 plants, whereas it was maintained in mpk3-1, compared to wild-type plants (Fig. 1). Remarkably, a lesser degree of protection was observed in mpk3-1; indeed, the mean lesion area in elicitor-treated mpk3-1 plants was reduced by 30% to 35%, with respect to control-treated plants, whereas a 60% to 65% reduction was observed in wild-type plants (Fig. 1). To rule out the possibility that the observed phenotypes are due to the insertion of extra T-DNA copies in the genome of mpk3-1 and mpk6-2 mutants, we tested elicitor-induced resistance in one additional mutant allele for each MAPK, namely MPK3-DG, a mutant obtained by fast neutron bombardment, in which a 6.3-kb deletion removed the two last exons and the 3′-untranslated region of MPK3, and a MPK6-RNAi transgenic line expressing an interfering RNA construct of 300 bp spanning a portion of the 5′-untranslated region and adjacent coding region of MPK6 (Miles et al., 2005). These lines did not accumulate detectable transcripts of the corresponding genes in adult leaves (Supplemental Fig. S1B). MPK3-DG plants displayed enhanced susceptibility to B. cinerea and were protected by pretreatment with OGs at an extent similar to that observed in mpk3-1 plants (Supplemental Fig. S2). MPK6-RNAi plants, like mpk6-2 plants, showed wild-type-like basal resistance to the fungus but had lost OG-induced resistance (Supplemental Fig. S2). These results confirm that loss of MPK3 affects basal, but not induced resistance to B. cinerea, whereas loss of MPK6 specifically impairs elicitor-induced protection.

Figure 1.

Elicitor-induced resistance to B. cinerea in mapk mutants. Col-0 (WT), mpk6-2, mpk3-1, and pad3 mutants were infiltrated with water (H), 100 μg mL−1 OGs (O), or 10 nm flg22 (F) and inoculated with B. cinerea 24 h after treatment. Lesion areas were measured 48 h after inoculation. Values are means ± se (n ≥ 10). Different letters above bars indicate statistically significant differences between samples, according to one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (P ≤ 0.05). The experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

Mutations in MPK3 and MPK6 Do Not Impair Sensitivity to ET

The plant hormone ET is required for basal resistance to B. cinerea (Thomma et al., 1999; Díaz et al., 2002; Ferrari et al., 2003). Since MPK3 and MPK6 were suggested to play a role in ET signal transduction (Yoo et al., 2008), we wondered whether the increased basal susceptibility to B. cinerea of mpk3 mutants was due to a defective responsiveness to this hormone. To answer this question, we examined the triple response, a typical response to ET exposure, in etiolated wild-type and mutant seedlings grown in presence of different concentrations of 1-aminocyclo-propane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC). All tested doses of ACC induced a wild-type-like triple response in mpk3-1 and mpk6-2 seedlings (Fig. 2). As expected, ACC did not induce any effect in the ethylene insensitive2-1 (ein2-1) mutant (Guzmán and Ecker, 1990), which is compromised in ET signaling (Fig. 2). These results indicate that both mapk mutants respond normally to ET, and therefore that the increased basal susceptibility of mpk3 plants to B. cinerea cannot be explained with an altered signal transduction of this hormone.

Figure 2.

Triple response in transgenic and mutant seedlings. Col-0 untransformed seedlings (WT), transgenic seedlings overexpressing AP2C1 (640.1 and 640.2), and mutant mpk3-1 (m3), mpk6-2 (m6), and ein2-1 seedlings were grown vertically in the dark on Murashige and Skoog (MS) solid medium supplemented or not with the indicated ACC concentrations. Bars represent average hypocotyl length ± se. Differences between control- and ACC-treated plants were statistically significant for all genotypes at both ACC concentrations, according to Student’s t test (P < 0.001), with the exception of ein2-1. For each genotype, the percentage of hypocotyl length of ACC-treated seedlings, with respect to Murashige and Skoog-grown seedlings (100%), is indicated by the numbers above bars. The number of samples analyzed for each condition was n ≥ 23, with the exception of mpk6-2 (n ≥ 15) and ein2-1 (n ≥ 10). This experiment was repeated three times with similar results. Picture shows two representative seedlings of the indicated genotypes for each treatment.

Role of MPK3 and MPK6 in Elicitor-Induced Responses

Since MPK3 and MPK6 appear to play different roles in elicitor-induced resistance to pathogen infection, we next investigated their individual contribution to additional responses activated by OGs or flg22. Wild-type and mutant seedlings were incubated for 30 min with OGs, flg22, or water, and the expression of different elicitor-responsive genes was analyzed. In particular, we monitored the expression of FLG22-INDUCED RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE1 (FRK1), which is specifically regulated by MAPKs, of At1g26380 (RetOx), which is activated by both calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs) and MAPKs but with a dominant contribution of MAPKs, and of PHOSPHATE-INDUCED1 (PHI1), a gene specifically activated by CDPKs (Boudsocq et al., 2010). The expression of these genes was previously shown to be induced by either OGs or flg22 (Denoux et al., 2008).

Elicitor-induced expression of RetOx and FRK1 was similar in wild-type and mpk3-1 seedlings (Fig. 3A; Supplemental Fig. S3), but it was reduced in the mpk6-2 mutant (Fig. 3B). On the contrary, elicitor-induced expression of PHI1 was unaffected in both mpk3-1 and mpk6-2 mutants (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Figs. S3 and S4), consistently with the observation that this gene is not regulated by MAPKs (Boudsocq et al., 2010). Notably, basal levels of RetOx, but not of PHI1, were also slightly reduced in mpk6-2 seedlings (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Expression of elicitor-responsive genes in mpk3-1 and mpk6-2 mutant seedlings. Col-0 (WT) and mpk3-1 (A) or mpk6-2 (B) seedlings were treated with water (H), 100 μg mL−1 OGs (O), or 10 nm flg22 (F) for 30 min. Expression of the indicated genes was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. Bars indicate average expression ± sd of three technical replicates. These experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

We also investigated flg22-induced inhibition of seedling growth, a long-term response induced by this MAMP (Gómez-Gómez and Boller, 2000). No major differences between wild-type, mpk3-1, and mpk6-2 seedlings grown in presence of 10 or 100 nm flg22 were observed (Fig. 4). As expected, Wassilewskija wild-type seedlings, which lack a functional FLS2 (Zipfel et al., 2004), were completely insensitive to flg22 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of growth in response to flg22 in mutant and transgenic seedlings. Untransformed Col-0 and Wassilewskija (Ws) seedlings, transgenic seedlings overexpressing AP2C1 (640.1 and 640.2), and mpk3-1 (m3) and mpk6-2 (m6) mutant seedlings were grown for 10 d in Murashige and Skoog (MS) in presence or not of flg22 (n ≥ 10 for each treatment). The experiment shown is representative of at least two biological replicates for each condition.

Elicitor-Induced Phosphorylation of Both MPK3 and MPK6 Is Prevented by the Overexpression of the Phosphatase AP2C1

A previous report demonstrated that MPK6 can be dephosphorylated by the Arabidopsis PP2C Ser/Thr protein phosphatase AP2C1 (Schweighofer et al., 2007). The expression of AP2C1 gene is up-regulated in response to several MAMPs, as shown by publicly available microarray data (Supplemental Fig. S5), and we also observed that it is transiently up-regulated in response to OGs and flg22 (Supplemental Fig. S1D). These observations prompted us to investigate whether AP2C1 acts as a negative regulator of MAPKs in DAMP- and MAMP-triggered immunity.

Elicitor-induced MAPK phosphorylation was therefore analyzed in two independent transgenic lines overexpressing AP2C1 fused to the GFP (lines 640.1 and 640.2; Schweighofer et al., 2007). The overexpression of AP2C1 in 640.1 and 640.2 seedlings was confirmed by both reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (Supplemental Fig. S1C) and immunoblot analyses (Fig. 5). Seedlings were treated with OGs, flg22, or water, as a negative control, and immunoblot analyses were performed using total protein extracts and an antiphospho-p44/p42 antibody that specifically recognizes the phosphorylated forms of MPK3 and MPK6 (Saijo et al., 2009) as well as an anti-GFP antibody to detect the AP2C1-GFP fusion protein. The null mpk3-1 and mpk6-2 mutants were also included in this analysis, to verify that elicitor treatment did not activate the corresponding missing kinase and confirm the identity of the bands detected with the antiphospho-p44/p42 antibody. AP2C1-GFP was expressed at similar levels in lines 640.1 and 640.2 plants (Fig. 5). Treatment of wild-type seedlings with either OGs or flg22 led to a strong activation of MPK3 and MPK6, whereas phosphorylation of both MAPKs was severely reduced in lines 640.1 and 640.2 (Fig. 5; Supplemental Fig. S6). Since AP2C1 was previously shown to specifically dephosphorylate MPK6 and MPK4, but not MPK3 (Schweighofer et al., 2007), we wondered whether the reduced levels of MPK3 phosphorylation in the elicitor-treated transgenic seedlings could be due to alterations in total levels of the two proteins. However, levels of both MPK3 and MPK6 were comparable in wild-type and transgenic seedlings (Fig. 5), as determined incubating the same membrane with antibodies against total MPK3 and MPK6. This indicates that the observed reduction of MPK3 phosphorylation was not due to reduced protein levels.

Figure 5.

Phosphorylation of MAPKs in response to elicitors in transgenic and mutant seedlings. Seedlings of Col-0 (WT), transgenic lines overexpressing AP2C1 (640.1 and 640.2), mpk3-1 (m3), and mpk6-2 (m6) null mutants were treated with water for 15 min (−) or with 100 μg mL−1 OGs (A) or 10 nm flg22 (B) for the indicated times. Samples were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies against phospho-p44/p42 (α-pTEpY), MPK3, and MPK6 total proteins (α-M3 + α-M6) or GFP (α-GFP). Bands corresponding to MPK3 and MPK6 total proteins, phosphorylated MAPKs (pMPK3 or pMPK6), and AP2C1-GFP protein are indicated by arrowheads. Rubisco large subunit was used as loading control. These experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

Expression of Only a Subset of Elicitor-Induced Defense Responses Is Negatively Regulated by AP2C1

To assess whether overexpression of AP2C1 affects responses induced by elicitors, wild-type and AP2C1-overexpressing seedlings were incubated with OGs, flg22, or water, and transcript levels of the same set of marker genes analyzed in single mapk mutants were determined. Up-regulation of RetOx and FRK1 in response to either OGs or flg22 was significantly hampered in both 640.1 and 640.2 transgenic lines, compared to wild-type seedlings (Fig. 6). A similar trend was observed in time-course experiments, where both RetOx and CYP81F2, another gene whose expression is mainly regulated by MAPKs (Boudsocq et al., 2010), showed reduced induction by OGs in the transgenic lines (Supplemental Fig. S7, A and B). Interestingly, basal levels of RetOx and FRK1 transcripts were also reduced (Fig. 6; Supplemental Fig. S7A, inset). A reduction of the basal levels of MAPK-dependent marker genes is likely a consequence of the constitutive presence of AP2C1, which may target MAPKs even in absence of stimuli. On the contrary, overexpression of AP2C1 did not impair basal or elicitor-induced expression of PHI1 (Fig. 6). These results show that expression of the marker genes in the AP2C1 plants mirrors that observed in the mpk6-2 single mutant.

Figure 6.

Expression of elicitor-responsive genes in seedlings overexpressing AP2C1. Col-0 untransformed seedlings (WT) and transgenic seedlings overexpressing AP2C1 (640.1 and 640.2) were treated with water (−) or 100 μg mL−1 OGs (A) or 10 nm flg22 (B; +) for 30 min. Expression of the indicated genes was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR, using UBQ5 as a reference. Bars indicate average expression ± sd of three technical replicates. These experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

Analysis of mapk single mutants suggests either a minor role or functional redundancy of MPK3 and MPK6 in the early oxidative burst induced by elicitors (Mersmann et al., 2010; Ranf et al., 2011). For this reason, this response was here analyzed in the AP2C1-overexpressing lines, which are affected in phosphorylation of both MAPKs. Hydrogen peroxide production was measured in response to water or flg22 in leaf disks of these plants and compared to that of wild-type and atrbohD knock-out (KO) plants, used as positive and negative controls, respectively. AtrbohD encodes a NADPH-oxidase required for elicitor-induced production of ROS (Torres et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2007; Galletti et al., 2008). As shown in Figure 7, both 640.1 and 640.2 plants produced wild-type-like levels of hydrogen peroxide upon stimulation with 10 nm flg22, whereas, as expected, the oxidative burst was completely abolished in leaf disks from atrbohD plants. These data strengthen the conclusion that the activation of MPK3 and MPK6 is not required for the early elicitor-triggered oxidative burst, and support the hypothesis that this response is independent of MAPK activation (Boudsocq et al., 2010) and may be instead regulated by CDPK phosphorylation (Benschop et al., 2007; Kobayashi et al., 2007).

Figure 7.

Oxidative burst in response to flg22 in mutant and transgenic plants. Leaf disks from adult Col-0 plants (WT), from transgenic plants overexpressing AP2C1 (640.1 and 640.2), and from the atrbohD mutant were treated with water, as control, or with 10 nm flg22. ROS production was measured with a luminol-based assay. Luminescence is shown as relative light units (RLU). Results are averages ± se (n ≥ 6 or n ≥ 10 for water- or elicitor-treated disks, respectively). This experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

We finally investigated flg22-induced seedling growth inhibition in the AP2C1-overexpressing lines. Seedlings from both lines (640.1 and 640.2) showed a response to 10 and 100 nm flg22 similar to that of the wild type, with an average growth inhibition of 25% and 60%, respectively, compared to control-treated seedlings (Fig. 4). Thus, flg22-induced seedling growth inhibition is not affected by AP2C1 overexpression.

Overexpression of AP2C1 Affects Basal Resistance and Suppresses Elicitor-Induced Protection against B. cinerea

The overexpression of AP2C1 and the concurrent dephosphorylation of MPK3 and MPK6 is likely to affect also elicitor-induced resistance. To verify this, adult leaves of wild-type, 640.1, and 640.2 plants were infiltrated with water, OGs, or flg22 and, after 24 h, were inoculated with B. cinerea. Both transgenic lines, like mpk6-2 and MPK6-RNAi plants, failed to display a reduction of lesion development after pretreatment with either elicitor (Fig. 8). Additionally, they showed an increase of basal susceptibility to B. cinerea, similar to what was observed in the mpk3-1 and MPK3-DG plants (Fig. 8) and in agreement with a previous report (Schweighofer et al., 2007). Like in mpk3 single mutants, the increased basal susceptibility is unlikely due to defects in ET perception and/or transduction, since both transgenic lines overexpressing AP2C1 showed a wild-type-like triple response when grown in presence of ACC (Fig. 2).

Figure 8.

Elicitor-induced resistance to B. cinerea in plants overexpressing AP2C1. Col-0 untransformed plants (WT) and transgenic plants overexpressing AP2C1 (640.1 and 640.2) were infiltrated with water (H), 100 μg mL−1 OGs (O), or 10 nm flg22 (F) and inoculated with B. cinerea 24 h after treatment. A, Lesion areas were measured 48 h after inoculation. Values are means ± se (n ≥ 14). Different letters above bars indicate statistically significant differences between samples, according to one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (P ≤ 0.05). The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. B, Representative pictures of infected leaves.

We also generated mpk3-1 plants overexpressing AP2C1-GFP (hereafter indicated as m3 × 640.1 plants) by crossing the mpk3-1 null mutant with the transgenic line 640.1 (Supplemental Fig. S8, A and B). The presence of AP2C1-GFP and the absence of MPK3 protein in m3 × 640.1 plants were verified by immunoblot analysis using anti-GFP and antitotal MPK3 antibodies, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S8C). Immunoblot analysis with the antiphospho-p44/p42 antibody confirmed a dramatic reduction of MPK6 phosphorylation in response to elicitors with respect to the wild type and, as expected, the absence of a signal for the phosphorylated form of MPK3 (Supplemental Fig. S8C). When infected with B. cinerea, m3 × 640.1 plants exhibited both increased basal susceptibility to the fungus and absence of OG-induced protection, a phenotype similar to that of the parental line 640.1 (Supplemental Fig. S9). Notably, the reduction of basal resistance observed in m3 × 640.1 plants was comparable to that observed in mpk3-1 and 640.1 plants, showing that the susceptibility of AP2C1-overexpressing plants is not further increased when MPK3 is lacking. Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that MPK3 play a major role in basal resistance against B. cinerea, whereas MPK6 is more important for elicitor-induced resistance.

Finally, OG-induced resistance to B. cinerea was determined in an ap2c1 null mutant (Supplemental Fig. S1D), which was previously shown to have unaltered basal resistance to this pathogen (Schweighofer et al., 2007), but increased phosphorylation of MPK3, MPK4, and MPK6 in response to flg22 (Brock et al., 2010). As expected, fungal lesion development in water-treated wild-type and ap2c1 plants was not significantly different; OG-induced resistance to B. cinerea was also similar to that of the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S10). Furthermore, expression of RetOx, PHI1, and CYP81F2 induced by OGs in wild-type and ap2c1 seedlings was not significantly different (Supplemental Fig. S11). These data suggest that AP2C1 is dispensable for these elicitor-induced responses.

DISCUSSION

Comprehension of the role of MAPKs in plant responses to internal and external stimuli is a challenging task. Functional redundancy, pleiotropic phenotypes caused by simultaneous mutations in multiple kinases, positive and negative regulatory interactions, as well as methodological pitfalls complicate the study of MAPK modules. In this work, we used plants mutated or silenced in single MAPK genes as well as plants overexpressing a MAPK phosphatase to investigate the specific role and the contribution of MPK3 and MPK6 to elicitor-induced resistance against the necrotrophic fungus B. cinerea.

Many observations indicate that MPK3 and MPK6 do not play completely overlapping roles in defense. For instance, MPK3 is an important regulator of benzothiadiazole-induced priming of defense gene activation, while MPK6 appears to play a minor role in this response (Beckers et al., 2009). Furthermore, MPK6 has a stronger effect on the up-regulation of genes involved in camalexin biosynthesis that are induced by the expression of a constitutively active MAPKKK, while MPK3 plays a major role in camalexin accumulation and disease development during B. cinerea infection (Ren et al., 2008). Moreover, ET production during infection with this fungus is unaffected in the mpk3 single mutant, slightly decreased in mpk6, but severely compromised in the double mutant mpk3 mpk6 (Han et al., 2010), indicating a redundant function, but again different contributions, of the two kinases.

Our results confirm the greater contribution of MPK3 to the maintenance of basal resistance to B. cinerea and reveal that the main player in elicitor-triggered resistance is MPK6. These data support the notion that MPK3 and MPK6 do not play equivalent roles in the immune response and differentially contribute to resistance against B. cinerea. To corroborate the importance of MPK6 in elicitor-triggered resistance, we also analyzed plants overexpressing the Arabidopsis PP2C phosphatase A2PC1, which was previously shown to block phosphorylation of MPK6 and MPK4 during wounding (Schweighofer et al., 2007). These plants, differently from mpk6 single mutants, also show increased basal susceptibility to B. cinerea (Schweighofer et al., 2007), a phenotype shown by mpk3 plants (Ren et al., 2008). Our observation that AP2C1-overexpressing plants display a strongly reduced phosphorylation of both MPK6 and MPK3 in response to elicitation helps explain these results. Indeed, phenotypes of AP2C1-overexpressing plants recapitulate that observed in the single mapk mutants, with both an increase in basal susceptibility to B. cinerea and a loss of elicitor-induced resistance, and this phenotype is not exacerbated when AP2C1 is overexpressed in the mpk3-1 background. However, since MPK4 is also a substrate for AP2C1 (Schweighofer et al., 2007), we cannot exclude that a reduced phosphorylation of this MAPK may also contribute to the phenotypes observed in the transgenic lines.

The lack of protection observed in the in AP2C1-overexpressing plants, as well as in mpk6 single mutants, cannot be explained with a decreased ET production during infection since an intact ET-dependent signaling is not required for elicitor-induced protection against B. cinerea (Ferrari et al., 2007). Therefore, other defense mechanisms downstream of MPK6 activation, for example camalexin accumulation (Ren et al., 2008), may play a more relevant role. Lack of MPK3 in mpk3-1 and MPK3-DG mutants and dephosphorylation of this MAPK by overexpression of AP2C1 impair basal resistance to B. cinerea to a similar degree, suggesting that MPK3 is almost completely inactivated when high levels of AP2C2 are present. It has been recently shown that lack of either AP2C1 or of the closely related PP2C5 results in increased activity of MPK3 and MPK6 in response to Flg22 (Brock et al., 2010), supporting our conclusion that AP2C1 is a negative regulator of both MAPKs. On the other hand, lack of AP2C1 is not sufficient to significantly increase activation of defense responses effective against B. cinerea, since both basal (Schweighofer et al., 2007) and induced resistance to this pathogen are not affected in ap2c1 null plants.

The ectopic expression of AP2C1 significantly hampers also elicitor-induced expression of MAPK-specific marker genes, such as FRK1, RetOx, or CYP81F2, whereas has no effect on the expression of PHI1, whose activation in response to flg22 is dependent on CDPKs (Boudsocq et al., 2010). FRK1 and RetOx expression is altered, although to a lesser extent, also in mpk6-2 plants, but not in the mpk3-1 mutant, supporting our observation that MPK6 plays a predominant role in the activation of some defense responses upon elicitor treatment. Recent evidence indicates that the early oxidative burst induced by flg22 or elf8 is not impaired, or it is even slightly enhanced, in single mpk3 or mpk6 mutants (Mersmann et al., 2010; Ranf et al., 2011). These data suggest that either MPK3 and MPK6 have a fully redundant role in this elicitor-triggered response or, conversely, that they are not required at all for this response; the latter hypothesis is supported by the wild-type-like oxidative burst observed in AP2C1-overexpressing plants treated with flg22 (this work).

Taken together, our results support a recently proposed model, according to which only a subset of elicitor-induced responses requires the activation of a MAPK cascade, whereas other responses, including PHI1 expression and production of ROS, rather depend on CDPKs (Boudsocq et al., 2010). Our findings also indicate that both elicitor-triggered MAPK activation and elicitor-induced resistance against B. cinerea can be uncoupled from the oxidative burst, consistently with our previous work showing that elicitor-induced protection against B. cinerea occurs independently of the plasma membrane NADPH oxidase AtrbohD, which is the main source of ROS produced within minutes in response to OGs (Galletti et al., 2008) and flg22 (Zhang et al., 2007).

Finally, we have shown that MPK3 and MPK6 do not play a major role also in flg22-induced seedling growth. This response was shown to be dependent on flg22-induced stabilization of DELLA proteins, which are plant growth repressors whose degradation is promoted by the phytohormone GA (Navarro et al., 2008). Since one of the fastest responses to GA is an increase in the concentration of cytosolic Ca2+ (Kuo et al., 1996), and CDPKs have been implicated in GA-mediated signaling (Ishida et al., 2008), it is tempting to speculate that flg22-mediated stabilization of DELLA proteins may be downstream of CDPKs, rather than of MPK3 and MPK6.

In conclusion, our results indicate that MPK3 and MPK6 are differently required for the activation of responses important for basal resistance to B. cinerea and for elicitor-triggered responses effective against this fungus, and that only the simultaneous inactivation of both MAPKs strongly compromises both lines of defense.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) Columbia-0 (Col-0) and Wassilewskija wild-type seeds were purchased from Lehle Seeds. Arabidopsis transgenic lines 640.1 and 640.2, ectopically expressing AP2C1 fused to GFP, and the ap2c1 KO mutant were kindly donated by Irute Meskiene (Max F. Perutz Laboratories, University of Vienna). The atrbohD KO line (Torres et al., 2002) was kindly provided by Jonathan G.D. Jones (Sainsbury Laboratory, John Innes Centre). Seeds of ein2-1 were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (Ohio State University). The pad3-1 mutant was previously described (Glazebrook and Ausubel, 1994). The MPK3-DG deletion mutant and the MPK6-RNAi line (Miles et al., 2005) were a kind gift of B.E. Ellis (University of British Columbia, Vancouver).

Seeds of the T-DNA insertional mutants mpk6-2 (SALK_073907) and mpk3-1 (SALK_151594) were obtained from Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (School of Biosciences, University of Nottingham, United Kingdom; Alonso et al., 2003). T-DNA insertion lines were genotyped using T-DNA left border (Lba1) and gene-specific primers (mpk3-1 LP: ATTTTTGTCAACAATGGCCTG; mpk3-1 RP: TCTGCCTTTTCACGGAATATG; mpk6-2 LP: CTCTGGCTCATCGCTTATGTC; mpk6-2 RP: ATCTATGTTGGCGTTTGCAAC).

To generate m3 × 640.1 plants, mpk3-1 homozygous plants were crossed with the transgenic line 640.1. F2 plants homozygous for the mpk3-1 mutation and carrying the AP2C1-GFP transgene were identified by PCR, performed as in Galletti et al. (2008), using genomic DNA as template. Genomic DNA was extracted from leaf tissues with the Edward’s method (Edwards et al., 1991). The T-DNA insertion in MPK3 was verified with the same primer pairs used for the parental line. The presence of the AP2C1-GFP transgene was verified by PCR using previously described primers (AP1-Fw and AP2C1-Rev) spanning the intron of the endogenous gene (Schweighofer et al., 2007) and resulting in a product of 1,145 bp in the case of the transgene and of 1,423 bp in the case of the endogenous gene.

All mutant and transgenic lines used in this work are in the Col-0 background.

Growth Conditions and Plant Treatments

Plants were grown on soil (Einheitserde) at 22°C and 70% relative humidity under a 16 h/8 h light/dark cycle (approximately 120 μmol m−2 s−1). For seedling treatments, seeds were surface sterilized and germinated in multiwell plates (approximately 10 seeds per well) containing 1 mL per well of Murashige and Skoog medium (Sigma-Aldrich; Murashige and Skoog, 1962) supplemented with 0.5% Suc. Plates were incubated at 22°C with a 16 h/8 h light/dark cycle and a light intensity of 120 μmol m−2 s−1.

Production of OGs and flg22 and plant treatments were performed as described in Galletti et al. (2008). OGs and flg22 concentrations were 100 μg mL−1 and 10 nm, respectively, in all experiments, unless otherwise stated.

Gene Expression Analysis

Seedlings were frozen in liquid nitrogen, homogenized with a mortar and pestle, and total RNA was extracted with Isol-RNA lysis reagent (5 Prime) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega) and first-strand cDNA was synthesized using ImProm-II reverse transcriptase (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Real-time quantitative PCR analysis was performed using a CFX96 real-time system (Bio-Rad). One microliter of a 1:5 dilution of cDNA (corresponding to 30 ng of total RNA) was amplified in 30 μL of reaction mix containing 1X SYBR Green JumpStar Taq ReadyMix (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.4 mm of each primer. Expression levels of each gene, relative to UBQ5, were determined using a modification of the Pfaffl method (Pfaffl, 2001) as previously described (Ferrari et al., 2006).

RT-PCR analysis was performed as described in Galletti et al. (2008). Primers for UBQ5, RetOx, and CYP81F2, used for transcript analyses, were the same as in Galletti et al. (2008). Primers for PHI1 and AP2C1 were previously described by Boudsocq et al. (2010) and Schweighofer et al. (2007), respectively. Primers for analysis of FRK1, MPK3, and MPK6 transcripts were the following: FRK1 F: TGCACTTACCCTCCTTCG; FRK1 R: GACAGTAGAAGCCGGTTGGT; MPK3 F: CCAGCTACTTCGAGGACTGA; MPK3 R: TGAGTGCTATGGCTTCTTGG; MPK6 F: ATGGACGGTGGTTCAGGTCAAC; and MPK6 R: TAAAGAAAATACTGGCAATGTTC.

Analyses of public microarray data were performed by using Genevestigator tools (Zimmermann et al., 2004).

Measurement of ROS

Leaf discs (0.125 cm2) from 5-week-old plants were incubated overnight in sterile water in a 96-well titer plate (Thermo Scientific NUNC), using one disc per well. ROS production was measured by a luminol-based assay in an aqueous solution containing 30 μg mL−1 luminol (Sigma-Aldrich) and 20 μg mL−1 type VI-A horseradish peroxidase (Sigma-Aldrich). Luminescence, indicated in relative light units, was measured by using a GloMax 96 microplate luminometer with dual injectors (Promega), and signal integration time was 1 s.

Protein Extraction and Immunoblot Analysis

Seedlings were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and proteins were extracted with a buffer containing 50 mm Tris at pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm NaF, 2 mm sodium orthovanadate, 1 mm sodium molybdate, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1% Tween 20, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail P9599 (Sigma-Aldrich).

Equal amounts of proteins (from 15–20 μg) were resolved on 7.5% polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto a nylon membrane (Biorad). Primary antibodies against MPK3 and MPK6 (Sigma-Aldrich), against phospho-p44/42 MAP kinase (Cell Signaling Technologies), and against GFP (Sigma-Aldrich) were used with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antirabbit as secondary antibody. Signal detection was performed using the ECL western detection kit (GE Healthcare).

Growth Inhibition Assay

Seedlings were grown for 5 d on half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar plates supplemented with 0.5% Suc, and were then transferred to 24-well plates containing liquid Murashige and Skoog medium supplemented with 0.5% Suc alone or containing 10 or 100 nm flg22 (one seedling in 500 μL of medium per well). After 10 d of incubation, fresh weight of each seedling was determined.

Protection Assay

Botrytis cinerea growth and protection assays on detached leaves were performed as previously described (Ferrari et al., 2007) with slight modifications. Intact rosette leaves were syringe infiltrated with water, OGs (100 μg mL−1), or flg22 (10 nm), or sprayed until run off with water or OGs (200 μg mL−1), as indicated in the figure legends. After 24 h, leaves were detached and inoculated with the fungus; lesion area was determined at 48 h post inoculation.

ET Sensitivity Assay

Arabidopsis seeds were surface sterilized, stratified for 2 d at +4°C in the dark, and sown in a single row on Murashige and Skoog agar plates supplemented with 0.5% (w/v) Suc alone or containing different concentrations of ACC (Sigma-Aldrich).

To allow seeds germination, plates were kept for 4 h under continuous white light (120 μmol m−2 s−1), then wrapped in three aluminum foils and incubated vertically for 4 d in a growth chamber at 22°C. As previously reported (Müller et al., 2010), we found that about the 26% to 43% of mpk6-2 seedlings showed major developmental defects with a no root or short root phenotype, that were recovered after 10 to 12 d. Noteworthy, dark-grown mpk6-2 mutants displaying the no root-short root phenotypes also had a very short hypocotyl, suggesting an overall effect of the mpk6-2 mutation on seedling development, though with incomplete penetrance (Supplemental Fig. S12). We did not include morphologically altered seedlings in the analyses.

Photographs were taken with a digital camera and hypocotyls length was measured by using ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/index.html).

Accession numbers of sequences relevant for this article are as follows: At3g62250 (UBQ5), At1g26380 (RetOx), At5g57220 (CYP81F2), At2g19190 (FRK1), At1g35140 (PHI1), At3g45640 (MPK3), At2g43790 (MPK6), At2g30020 (AP2C1), and At3g26830 (PAD3).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Characterization of mutant and transgenic lines.

Supplemental Figure S2. Elicitor-induced resistance to B. cinerea in the MPK6-RNAi line and in the MPK3-DG deletion mutant.

Supplemental Figure S3. Expression of elicitor-responsive genes in mpk3-1 and mpk6-2 mutant seedlings.

Supplemental Figure S4. Expression of PHI1 in mpk3-1 mutant seedlings.

Supplemental Figure S5. Expression of AP2C1 gene in response to elicitors.

Supplemental Figure S6. MAPK activation in response to OGs in mutant and transgenic lines.

Supplemental Figure S7. Time-course expression analysis of elicitor-responsive genes in AP2C1-overexpressing seedlings.

Supplemental Figure S8. Characterization of mpk3-1 × 640.1 plants.

Supplemental Figure S9. Elicitor-induced resistance to B. cinerea in mpk3-1 × 640.1 plants.

Supplemental Figure S10. Elicitor-induced resistance to B. cinerea in ap2c1 plants.

Supplemental Figure S11. Expression of elicitor-responsive genes in ap2c1 seedlings.

Supplemental Figure S12. Phenotypes of etiolated mpk6-2 seedlings.

Acknowledgments

We thank Irute Meskiene (Max F. Perutz Laboratories, University of Vienna) for kindly providing seeds of Arabidopsis plants ectopically expressing AP2C1 and Brian E. Ellis (University of British Columbia, Vancouver) for the MPK3-DG deletion mutant and the MPK6-RNAi line. We also thank Michela Cassetta (Dipartimento di Biologia e Biotecnologie “Charles Darwin,” Sapienza Università di Roma) for technical assistance.

References

- Alonso JM, Stepanova AN, Leisse TJ, Kim CJ, Chen H, Shinn P, Stevenson DK, Zimmerman J, Barajas P, Cheuk R, et al. (2003) Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301: 653–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasson E, Jenkins T, Brodersen P, Thorgrimsen S, Petersen NH, Zhu S, Qiu JL, Micheelsen P, Rocher A, Petersen M, et al. (2005) The MAP kinase substrate MKS1 is a regulator of plant defense responses. EMBO J 24: 2579–2589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai T, Tena G, Plotnikova J, Willmann MR, Chiu WL, Gomez-Gomez L, Boller T, Ausubel FM, Sheen J. (2002) MAP kinase signalling cascade in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Nature 415: 977–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz A, Heyraud A, Lambert B. (2004) Oligogalacturonide signal transduction, induction of defense-related responses and protection of grapevine against Botrytis cinerea. Planta 218: 767–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckers GJ, Jaskiewicz M, Liu Y, Underwood WR, He SY, Zhang S, Conrath U. (2009) Mitogen-activated protein kinases 3 and 6 are required for full priming of stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 21: 944–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellincampi D, Dipierro N, Salvi G, Cervone F, De Lorenzo G. (2000) Extracellular H(2)O(2) induced by oligogalacturonides is not involved in the inhibition of the auxin-regulated rolB gene expression in tobacco leaf explants. Plant Physiol 122: 1379–1385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benschop JJ, Mohammed S, O’Flaherty M, Heck AJ, Slijper M, Menke FL. (2007) Quantitative phosphoproteomics of early elicitor signaling in Arabidopsis. Mol Cell Proteomics 6: 1198–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethke G, Unthan T, Uhrig JF, Pöschl Y, Gust AA, Scheel D, Lee J. (2009) Flg22 regulates the release of an ethylene response factor substrate from MAP kinase 6 in Arabidopsis thaliana via ethylene signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 8067–8072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudsocq M, Willmann MR, McCormack M, Lee H, Shan L, He P, Bush J, Cheng SH, Sheen J. (2010) Differential innate immune signalling via Ca(2+) sensor protein kinases. Nature 464: 418–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock AK, Willmann R, Kolb D, Grefen L, Lajunen HM, Bethke G, Lee J, Nürnberger T, Gust AA. (2010) The Arabidopsis mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase PP2C5 affects seed germination, stomatal aperture, and abscisic acid-inducible gene expression. Plant Physiol 153: 1098–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brutus A, Sicilia F, Macone A, Cervone F, De Lorenzo G. (2010) A domain swap approach reveals a role of the plant wall-associated kinase 1 (WAK1) as a receptor of oligogalacturonides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 9452–9457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casasoli M, Federici L, Spinelli F, Di Matteo A, Vella N, Scaloni F, Fernandez-Recio J, Cervone F, De Lorenzo G. (2009) Integration of evolutionary and desolvation energy analysis identifies functional sites in a plant immunity protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 7666–7671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KR, Darvill AG, Albersheim P, Dell A. (1986) Host-pathogen interactions. XXIX. Oligogalacturonides released from sodium polypectate by endopolygalacturonic acid lyase are elicitors of phytoalexins in soybean. Plant Physiol 80: 568–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lorenzo G, Brutus A, Savatin DV, Sicilia F, Cervone F. (2011) Engineering plant resistance by constructing chimeric receptors that recognize damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). FEBS Lett 585: 1521–1528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lorenzo G, Ferrari S. (2002) Polygalacturonase-inhibiting proteins in defense against phytopathogenic fungi. Curr Opin Plant Biol 5: 295–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denoux C, Galletti R, Mammarella N, Gopalan S, Werck D, De Lorenzo G, Ferrari S, Ausubel FM, Dewdney J. (2008) Activation of defense response pathways by OGs and Flg22 elicitors in Arabidopsis seedlings. Mol Plant 1: 423–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz J, ten Have A, van Kan JA. (2002) The role of ethylene and wound signaling in resistance of tomato to Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol 129: 1341–1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djamei A, Pitzschke A, Nakagami H, Rajh I, Hirt H. (2007) Trojan horse strategy in Agrobacterium transformation: abusing MAPK defense signaling. Science 318: 453–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards K, Johnstone C, Thompson C. (1991) A simple and rapid method for the preparation of plant genomic DNA for PCR analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 19: 1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari S, Galletti R, Denoux C, De Lorenzo G, Ausubel FM, Dewdney J. (2007) Resistance to Botrytis cinerea induced in Arabidopsis by elicitors is independent of salicylic acid, ethylene, or jasmonate signaling but requires PHYTOALEXIN DEFICIENT3. Plant Physiol 144: 367–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari S, Galletti R, Vairo D, Cervone F, De Lorenzo G. (2006) Antisense expression of the Arabidopsis thaliana AtPGIP1 gene reduces polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein accumulation and enhances susceptibility to Botrytis cinerea. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 19: 931–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari S, Plotnikova JM, De Lorenzo G, Ausubel FM. (2003) Arabidopsis local resistance to Botrytis cinerea involves salicylic acid and camalexin and requires EDS4 and PAD2, but not SID2, EDS5 or PAD4. Plant J 35: 193–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galletti R, Denoux C, Gambetta S, Dewdney J, Ausubel FM, De Lorenzo G, Ferrari S. (2008) The AtrbohD-mediated oxidative burst elicited by oligogalacturonides in Arabidopsis is dispensable for the activation of defense responses effective against Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol 148: 1695–1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Liu J, Bi D, Zhang Z, Cheng F, Chen S, Zhang Y. (2008) MEKK1, MKK1/MKK2 and MPK4 function together in a mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade to regulate innate immunity in plants. Cell Res 18: 1190–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook J, Ausubel FM. (1994) Isolation of phytoalexin-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana and characterization of their interactions with bacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 8955–8959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Gómez L, Boller T. (2000) FLS2: an LRR receptor-like kinase involved in the perception of the bacterial elicitor flagellin in Arabidopsis. Mol Cell 5: 1003–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán P, Ecker JR. (1990) Exploiting the triple response of Arabidopsis to identify ethylene-related mutants. Plant Cell 2: 513–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn MG, Darvill AG, Albersheim P. (1981) Host-pathogen interactions. XIX. The endogenous elicitor, a fragment of a plant cell wall polysaccharide that elicits phytoalexin accumulation in soybeans. Plant Physiol 68: 1161–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L, Li GJ, Yang KY, Mao G, Wang R, Liu Y, Zhang S. (2010) Mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 and 6 regulate Botrytis cinerea-induced ethylene production in Arabidopsis. Plant J 64: 114–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura K, Casais C, Peck SC, Shinozaki K, Shirasu K. (2006) MEKK1 is required for MPK4 activation and regulates tissue-specific and temperature-dependent cell death in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem 281: 36969–36976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida S, Yuasa T, Nakata M, Takahashi Y. (2008) A tobacco calcium-dependent protein kinase, CDPK1, regulates the transcription factor REPRESSION OF SHOOT GROWTH in response to gibberellins. Plant Cell 20: 3273–3288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihama N, Yamada R, Yoshioka M, Katou S, Yoshioka H. (2011) Phosphorylation of the Nicotiana benthamiana WRKY8 transcription factor by MAPK functions in the defense response. Plant Cell 23: 1153–1170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonak C, Okrész L, Bögre L, Hirt H. (2002) Complexity, cross talk and integration of plant MAP kinase signalling. Curr Opin Plant Biol 5: 415–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Ohura I, Kawakita K, Yokota N, Fujiwara M, Shimamoto K, Doke N, Yoshioka H. (2007) Calcium-dependent protein kinases regulate the production of reactive oxygen species by potato NADPH oxidase. Plant Cell 19: 1065–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo AL, Cappelluti S, Cervantes-Cervantes M, Rodriguez M, Bush DS. (1996) Okadaic acid, a protein phosphatase inhibitor, blocks calcium changes, gene expression, and cell death induced by gibberellin in wheat aleurone cells. Plant Cell 8: 259–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligterink W, Hirt H. (2001) Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways in plants: versatile signaling tools. Int Rev Cytol 201: 209–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao G, Meng X, Liu Y, Zheng Z, Chen Z, Zhang S. (2011) Phosphorylation of a WRKY transcription factor by two pathogen-responsive MAPKs drives phytoalexin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23: 1639–1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu Y, Kurkdijan A, Xia H, Guern J, Koller A, Spiro M, O'Neill M, Albersheim P, Darvill A. (1991) Membrane responses induced by oligogalacturonides in suspension-cultured tobacco cells. Plant J 1: 333–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menke FL, Kang HG, Chen Z, Park JM, Kumar D, Klessig DF. (2005) Tobacco transcription factor WRKY1 is phosphorylated by the MAP kinase SIPK and mediates HR-like cell death in tobacco. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 18: 1027–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersmann S, Bourdais G, Rietz S, Robatzek S. (2010) Ethylene signaling regulates accumulation of the FLS2 receptor and is required for the oxidative burst contributing to plant immunity. Plant Physiol 154: 391–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles GP, Samuel MA, Zhang Y, Ellis BE. (2005) RNA interference-based (RNAi) suppression of AtMPK6, an Arabidopsis mitogen-activated protein kinase, results in hypersensitivity to ozone and misregulation of AtMPK3. Environ Pollut 138: 230–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J, Beck M, Mettbach U, Komis G, Hause G, Menzel D, Samaj J. (2010) Arabidopsis MPK6 is involved in cell division plane control during early root development, and localizes to the pre-prophase band, phragmoplast, trans-Golgi network and plasma membrane. Plant J 61: 234–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. (1962) Revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco cultures. Physiol Plant 15: 437–479 [Google Scholar]

- Nakagami H, Soukupová H, Schikora A, Zárský V, Hirt H. (2006) A mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase mediates reactive oxygen species homeostasis in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem 281: 38697–38704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro L, Bari R, Achard P, Lisón P, Nemri A, Harberd NP, Jones JD. (2008) DELLAs control plant immune responses by modulating the balance of jasmonic acid and salicylic acid signaling. Curr Biol 18: 650–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen M, Brodersen P, Naested H, Andreasson E, Lindhart U, Johansen B, Nielsen HB, Lacy M, Austin MJ, Parker JE, et al. (2000) Arabidopsis map kinase 4 negatively regulates systemic acquired resistance. Cell 103: 1111–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. (2001) A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29: e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu JL, Fiil BK, Petersen K, Nielsen HB, Botanga CJ, Thorgrimsen S, Palma K, Suarez-Rodriguez MC, Sandbech-Clausen S, Lichota J, et al. (2008) Arabidopsis MAP kinase 4 regulates gene expression through transcription factor release in the nucleus. EMBO J 27: 2214–2221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranf S, Eschen-Lippold L, Pecher P, Lee J, Scheel D. (July 14, 2011) Interplay between calcium signalling and early signalling elements during defence responses to microbe- or damage-associated molecular patterns. Plant J http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04671.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren DT, Liu Y, Yang KY, Han L, Mao G, Glazebrook J, Zhang S. (2008) A fungal-responsive MAPK cascade regulates phytoalexin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 5638–5643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley BL, O’Neill MA, Mohnen D. (2001) Pectins: structure, biosynthesis, and oligogalacturonide-related signaling. Phytochemistry 57: 929–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijo Y, Tintor N, Lu XL, Rauf P, Pajerowska-Mukhtar K, Häweker H, Dong XN, Robatzek S, Schulze-Lefert P. (2009) Receptor quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum for plant innate immunity. EMBO J 28: 3439–3449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweighofer A, Kazanaviciute V, Scheikl E, Teige M, Doczi R, Hirt H, Schwanninger M, Kant M, Schuurink R, Mauch F, et al. (2007) The PP2C-type phosphatase AP2C1, which negatively regulates MPK4 and MPK6, modulates innate immunity, jasmonic acid, and ethylene levels in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19: 2213–2224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwessinger B, Zipfel C. (2008) News from the frontline: recent insights into PAMP-triggered immunity in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 11: 389–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Rodriguez MC, Adams-Phillips L, Liu Y, Wang H, Su SH, Jester PJ, Zhang S, Bent AF, Krysan PJ. (2007) MEKK1 is required for flg22-induced MPK4 activation in Arabidopsis plants. Plant Physiol 143: 661–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thain JF, Gubb IR, Wildon DC. (1995) Depolarization of tomato leaf cells by oligogalacturonide elicitors. Plant Cell Environ 18: 211–214 [Google Scholar]

- Thomma BP, Nelissen I, Eggermont K, Broekaert WF. (1999) Deficiency in phytoalexin production causes enhanced susceptibility of Arabidopsis thaliana to the fungus Alternaria brassicicola. Plant J 19: 163–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres MA, Dangl JL, Jones JD. (2002) Arabidopsis gp91phox homologues AtrbohD and AtrbohF are required for accumulation of reactive oxygen intermediates in the plant defense response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 517–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SD, Cho YH, Tena G, Xiong Y, Sheen J. (2008) Dual control of nuclear EIN3 by bifurcate MAPK cascades in C2H4 signalling. Nature 451: 789–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Shao F, Li Y, Cui H, Chen L, Li H, Zou Y, Long C, Lan L, Chai J, et al. (2007) A Pseudomonas syringae effector inactivates MAPKs to suppress PAMP-induced immunity in plants. Cell Host Microbe 1: 175–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou N, Tootle TL, Glazebrook J. (1999) Arabidopsis PAD3, a gene required for camalexin biosynthesis, encodes a putative cytochrome P450 monooxygenase. Plant Cell 11: 2419–2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P, Hirsch-Hoffmann M, Hennig L, Gruissem W. (2004) GENEVESTIGATOR: Arabidopsis microarray database and analysis toolbox. Plant Physiol 136: 2621–2632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel C, Robatzek S, Navarro L, Oakeley EJ, Jones JD, Felix G, Boller T. (2004) Bacterial disease resistance in Arabidopsis through flagellin perception. Nature 428: 764–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]