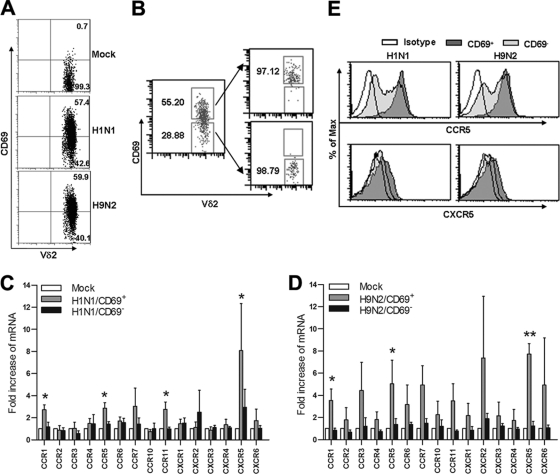

Fig. 2.

FluA virus-activated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells express type 1 chemokine receptors. (A and B) PBMCs were infected with mock, H1N1, or H9N2 virus at an MOI of 2. At 18 h p.i., the cells were stained for CD3, Vδ2, and CD69 and then analyzed by flow cytometry. CD69 expression in Vγ9Vδ2 T cells is shown after virus stimulation. Data shown are representative of five separate experiments. CD3+ Vδ2+ cells were sorted from mock-infected PBMCs, while CD3+ Vδ2+ CD69+ and CD3+ Vδ2+ CD69− cells were sorted from virus-infected PBMCs by FACSAria (B). (C and D) Total RNA was extracted from sorted cells, and gene expression levels of chemokine receptors were determined by relative quantitative real-time RT-PCR. The fold increase of chemokine receptor mRNA relative to the level in mock-treated γδ T cells (mean ± SEM) was calculated from CT values using the formula 2−ΔCT. A Newman-Keuls one-way ANOVA test was used to compare chemokine receptor expression levels in mock-treated cells and in virus-reactive CD69+ and CD69− subsets (n = 4). (E) PBMCs were infected by mock, H1N1, or H9N2 virus for 24 h. The cells were stained for CD3, Vδ2, CD69, CCR5, and CXCR5. Histogram plots of CCR5 and CXCR5 expression in CD69+ and CD69− Vδ2 T subsets are representative for four separate experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Max, maximum.