Abstract

Pituitary tumor-transforming gene (PTTG) is an oncogene with its expression levels correlating with tumor development and metastasis. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a crucial step in tumor progression and metastasis. Using ovarian epithelial tumor cell line (A2780) for loss-of-function or gain-of-function of PTTG in our experiments, we observed up regulation of TGF-β, twist, snail, slug, vimentin and down regulation of E-cadherin on infection of cells with Ad-PTTG cDNA. In contrast reverse phenomena was observed on depletion of PTTG on infection of cells with Ad-PTTG siRNA, suggesting an important role of PTTG in induction of EMT in ovarian cancer cells.

Keywords: PTTG, EMT, Ovarian cancer, TGF-β

1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the most common cause of death from gynecologic malignancies and ranks as the fifth most common cause of cancer deaths in women in the United States [1]. In 2010, approximately 21,880 new cases of ovarian cancer are expected to be diagnosed and 13,850 deaths from ovarian cancer [1]. Due to a lack of appropriate diagnosis and treatment for ovarian cancer, death rate from ovarian cancer remains unchanged for the last thirty years.

The human pituitary tumor transforming gene (PTTG), also known as securin, was first identified from a rat pituitary tumor cell line [2] followed by its cloning from humans [3–5]. High levels of PTTG expression has been described in a variety of human tumors, including thyroid, ovarian, breast, liver, lung, and various tumor cell lines reviewed in [6]. PTTG is an oncogene and its introduction into normal cells results in an increase in cell proliferation, induction of cellular transformation, and promotion of tumor in nude mice [2,7,8]. With respect to oncogenic function of PTTG, several studies reveal that PTTG plays a crucial role in cell-cycle progression, cell division, and chromosomal instability in addition to its involvement in tumor angiogenesis, malignant transformation and metastasis [9–12] implying that PTTG may be a fundamental oncogene involved in tumorigenesis.

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) was initially reported to be an important process in embryonic development, particularly during gastrulation and neural crest migration [13]. In EMT process epithelial cells lose their epithelial characteristics and acquire the properties of mesenchymal cells, and is reported to be associated with the progression and metastasis of cancer [14,15]. Loss of E-cadherin is a key initial step in the transdifferentiation of epithelial cells to a mesenchymal phenotype, which occurs when tumor epithelial cells invade into surrounding tissues [16]. Several transcription factors have been reported to be involved in EMT via repression of E-cadherin, and some of these include Twist, Snail, and Slug [17–20]. Several studies have shown that over expression of Snail and Slug lead to a reduction of E-cadherin expression. Similarly, an over expression of Twist also results in decrease of E-cadherin expression [21]. Analysis of the expression patterns of Slug, Snail, and E-cadherin in breast cancer cell lines demonstrated that the expression of Slug strongly correlated with a loss of E-cadherin transcripts.

TGF-β has long been known to be a major inducer of EMT, particularly in heart formation and palate fusion in mice, as well as in some mammary cells in mouse models of skin carcinogenesis [22,23]. TGF-β pathway has been studied in many metastatic processes and has been shown to be associated with tumor cells gaining the ability to spread throughout the body [24,25]. TGF-β has also been shown to regulate the expression of several transcription genes such as Twist, Snail, and Slug that repress expression of E-cadherin leading to induction of EMT [26]. TGF-β has also been described to induce EMT in ovarian adenosarcoma cells [27], mouse NMuMG breast epithelial tumor cells [28] and human lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549 [29].

In the present study, we showed for the first time role of PTTG in induction of EMT in human ovarian epithelial cancer cells. Such effects of PTTG are achieved through the regulation of TGF-β, Twist, Snail, Slug, E-cadherin, and vimentin.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Cell lines and cell culture

Human epithelial ovarian tumor cell line (A2780) was obtained from Dr. Denise Connolly (Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA). Cell line was cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and maintained in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C and 5% CO2. The cell line was cultured on a routine basis every 3–4 days.

2.2 Generation of plasmid and adenovirus constructs

The full length PTTG cDNA, PTTG siRNA, and control siRNA [30] were sub-cloned into adenovirus shuttle vector (pShuttle). Positive clones were sequenced to confirm the authenticity and orientation of sequence. The adenovirus expression systems were generated and purified in association with the Gene Therapy Center, Virus Vector Core Facility, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill as described previously [31].

2.3 Preparation of total RNA and synthesis of first strand cDNA

Cells after 48 h of infection with appropriate adenovirus were harvested and total RNA was purified using TRI-BD (Sigma, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as described previously [32]. The yield of total RNA was measured using a spectrophotometer, and the quality of RNA was assessed by electrophoresis through a 1% agarose gel. First strand cDNA was synthesized using the iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA) [31].

2.4 Quantitative real-time PCR

The real-time PCR reaction mixture was prepared in a Light Cycler® 480 (Roche Diagnostics) Multiwell 96 wells plate containing 1 µM of each primer, 10 µl of 2× master mix and 1µl of cDNA template, in a final reaction volume of 20 µl. The real-time PCR amplification was performed using the specific primers for PTTG, Twist, Snail, Slug, GAPDH, E-cadherin, vimentin and TGF-β (Table 1) using the following cycle parameters: enzyme activation at 95°C for 10 min; 45 cycles at 95°C for 10 s, 62°C for 10 s, and 65°C for 10 s. Following the amplification phase, a cooling step was performed at 40°C for 10 s (ramp rate of 1.5°C/s). Acquisitions of the fluorescence signal was performed using the Mono Hydrolysis Probe setting (483–523 nm) followed by 65°C extension phase of each cycle. GAPDH primers were included to normalize variation from sample to sample. All amplifications were repeated three times using cDNA prepared from three independent experiments.

Table I.

Primers Sequences for various genes

| Gene | Sequences |

|---|---|

| GAPDH | Sense 5’-TGA TGA CAT CAA GAA GGT GGT-3’ |

| Antisense 5’-TCC TTG GAG GCC ATG TGG GCC-3’ | |

| Twist | Sense 5’-GGA GTC CGC AGT CTT ACG AG-3’ |

| Antisense 5’-TCT GGA GGA CCT GGT AGA GG-3’ | |

| Snail | Sense 5’-CGC GCT CTT TCC TCG TCA G-3’ |

| Antisense 5’-TCC CAG ATG AGC ATT GGC AG-3’ | |

| Slug | Sense 5’-TTC GGA CCC ACA CAT TAC CT-3’ |

| Antisense 5’-GCA GTG AGG GCA AGA AAA AG-3’ | |

| E-Cadherin | Sense 5’-TGA CAC CCG GGA CAA CGT TTA TTA-3’ |

| Antisense 5’-CTA GTC TAG ACC CCT AGT GGT CCT CG-3’ | |

| Vimentin | Sense 5’-GAC AAT GCG TCT CTG GCA CGT CTT-3’ |

| Antisense 5’-TCC TCC GCC TCC TGC AGG TTC TT-3’ | |

| TGF-β | Sense 5’-TGA GCC AGA GGC GGA CTA CT-3’ |

| Antisense 5’-TGC CGT ATT CCA CCA TTA GCA-3’ |

2.5 Measurement of TGF-β

Effect of PTTG on TGF-β1 secretion in the culture medium was determined by enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) kit from Genzyme Diagnostics (Cambridge, MA), using natural human TGF-β1 as a standard. Approximately, 100,000 cells were plated in each well of 6-well plates. After 24 h of plating, cells were infected with Ad-PTTG cDNA, Ad-PTTG siRNA, Ad-GFP or Ad-control siRNA. After 24 h of infection, the medium was replaced by serum free medium. After 48 h of incubation, the medium was collected and centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 5 min to remove cell debris. The supernatants were stored at −20°C. All supernatants were acidified to pH 2 before TGF-β1 measurement. Cross-reactivity with other TGF-β isoforms was calculated be less than 2%.

2.6 Western blot analysis

Cells were plated in 6-well plates and infected with Ad-GFP, Ad-PTTG cDNA, Ad-PTTG siRNA or control Ad-siRNA as described above. After 48 h of infection, cells were washed with PBS and lysed in chilled lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 1 mM NaF] supplemented with Complete Mini Protease Inhibitor tablets (Roche Molecular Biochemical, Indianapolis, IN). Protein was quantitated using BSA as standard. Equal amounts of protein extracts (40 µg) from each sample was resolved on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel, and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Blots were probed with PTTG antiserum at a dilution of 1:1,500 as described previously [32]. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using the Enhanced Chemiluminescent Detection system (ECL) kit from GE Health System (Piscataway, NJ) according to instructions provided by the supplier. The membrane was stripped by using western blot stripping reagent (BioRad, Hercules, CA) and reprobed with monoclonal GAPDH antibody (Santa Cruz, CA) to normalize the variation in loading of samples.

2.7 Immunofluorescence

Cells were cultured in chamber slides and infected with adenovirus as described above. After 48 h of infection, cells were fixed with 2.0% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min and then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature. After intermediate washes with PBS, cells were incubated for 1 h with a polyclonal antibody for PTTG at a dilution of (1:1,000) or monoclonal antibody for E-cadherin at a dilution of (1:500) (BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA) or vimentin at a dilution of (1:1,000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, San Diego, CA, USA). After successive washes, cells were then exposed to Alexa Fluor 594 anti-rabbit for PTTG or Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse for E-cadherin and Alexa Fluor 594 anti-mouse for vimentin secondary antibodies. After incubation of secondary antibodies for 45 min, cells were washed with PBS and nuclei were labeled with DAPI for 20 min. The cover slips were then mounted with aquapolymount antifading solution and observed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus X-50) or with a MRC 600 confocal laser scanning microscope (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA).

2.8. Treatment with TGF-b1 neutralizing antibody

After 24 h of plating, cellswere infected with Ad-GFP and Ad-PTTG cDNA. After 24 h of infection, the medium was replaced by serum free medium and treated with TGF-b1 neutralizing antibody (Sigma, USA) at a final concentration of 2 lg/ml. Cells after 48 h of treatment were harvested and total RNA was purified using TRI-BD according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as described previously [32].

2.9 Statistical analysis

Data to compare differences between two groups were statistically analyzed using unpaired Student’s t-test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Overexpression and down-regulation of PTTG in A2780 cells

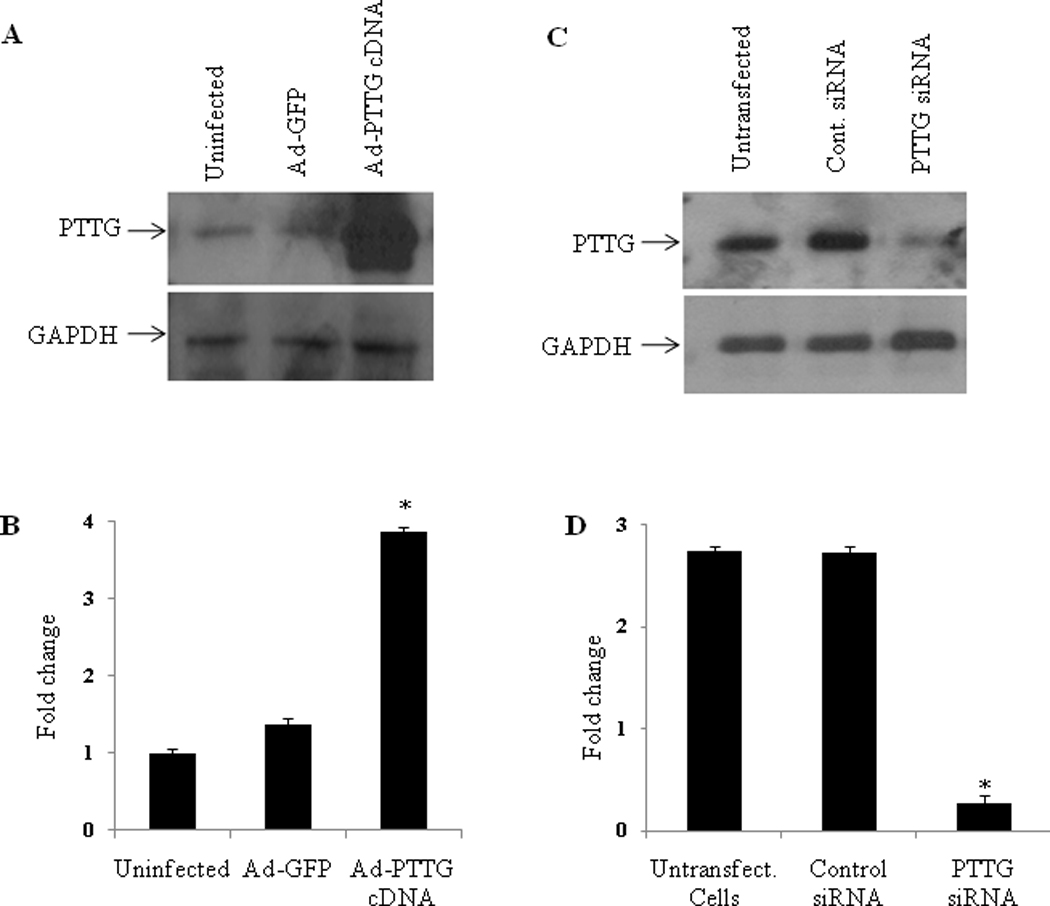

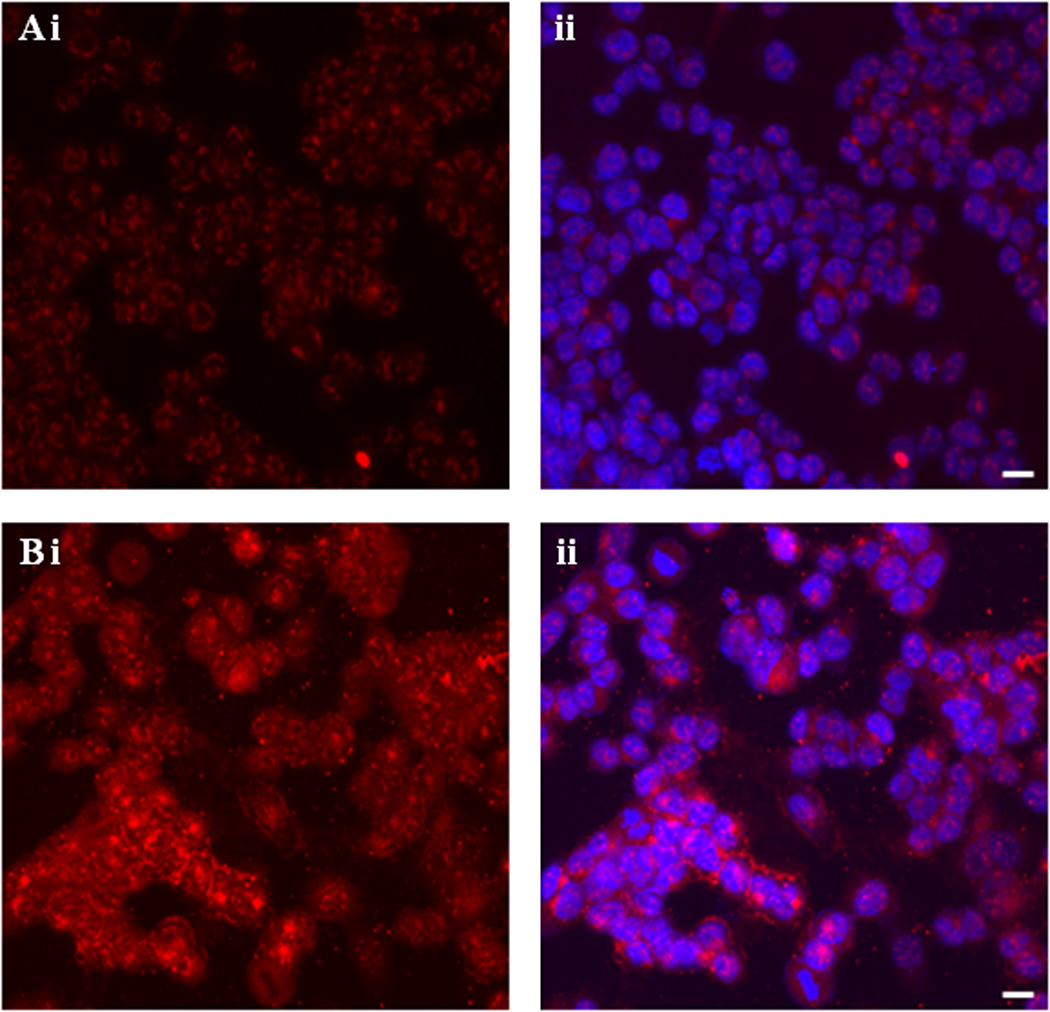

EMT is a crucial process in tumor progression and metastasis. Therefore, in the present study, we used in vitro experiments to understand the molecular mechanisms involved in induction of EMT by PTTG. For this purpose we generated adenovirus expression system expressing PTTG cDNA (Ad-PTTG cDNA) to overexpress PTTG and adenovirus expressing PTTG siRNA (Ad-PTTG siRNA) to down-regulate the expression of PTTG. As shown in Fig. 1 (A, B), Western blot analysis of A2780 cells infected with Ad-PTTG or Ad-PTTG siRNA using PTTG-specific polyclonal antibody [6], showed a significantly higher level of PTTG protein in A2780 cells infected with Ad-PTTG cDNA compared to uninfected cells or cells infected with control Ad-GFP vector. These results were confirmed by using immunohistochemical analysis. As shown in Fig. 2, infection of cells with Ad-PTTG cDNA resulted in a higher level of immunoreactive staining for PTTG protein (Fig. 2 Bi) compared to uninfected cells (Fig. 2 Ai). In contrast, Western blot analysis of A2780 cells infected with Ad-PTTG siRNA resulted in a significant down regulation of PTTG protein compared to uninfected cells or cells infected with control Ad-siRNA (Fig. 1C, D).

Figure 1.

Overexpression and downregulation of PTTG in A2780 cells. A: Western blot analysis for PTTG and GAPDH in A2780 cells. Cells were infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-PTTG cDNA for 48 h. Forty µg of protein from each sample was used for analysis. B: Densitometric analysis of PTTG expression in A2780 cells represented in A. Columns, mean (n = 3); bars, SEM. *P < 0.05. Values were normalized with GAPDH used as an internal control. C: Knockout of PTTG in A2780 cells. Western blot analysis for PTTG and GAPDH in A2780. Cells were infected with control Ad-siRNA or Ad-PTTG siRNA for 48 h. Forty µg of protein from each sample was used for analysis. D: Densitometric analysis of PTTG expression in A2780 cells represented in C. Columns, mean (n = 3); bars, SEM. *P < 0.05. Values were normalized with GAPDH used as an internal control.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence microscopy of A2780 cells. A: Uninfected cells. B: Cells infected with Ad-PTTG cDNA (i) PTTG protein was detected using Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody, (ii) double staining with Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody for PTTG and DAPI for nuclei. Bar shown in the right panels is 20 µM.

Morphological analysis of A2780 cells using a phase contrast microscope revealed changes in cells morphology from flat and elongated to round and spherical upon infection of A2780 cells with Ad-PTTG cDNA. These cells also showed formation of lamellipodia and filopodia (Fig. 3C), indicative of dissemination of cells to secondary sites and increase in invasive characteristics observed in EMT. These results support the hypothesis that overexpression of PTTG induces EMT in epithelial tumor cells.

Figure 3.

Induction of EMT by PTTG. A2780 cells after infection with Ad-PTTG cDNA for 48 h were examined under phase contrast microscope. Morphological changes from flat and elongated form to round and spherical shape, and appearance of lamellipodia and filopodia which extend from the leading edge of migrating cells indicating the step towards EMT are shown by arrows. A: Uninfected cells. B: Cells infected with Ad-GFP vector. C. Cells infected with Ad-PTTG cDNA.

3.2 PTTG up-regulates the expression of Twist, Snail, and Slug

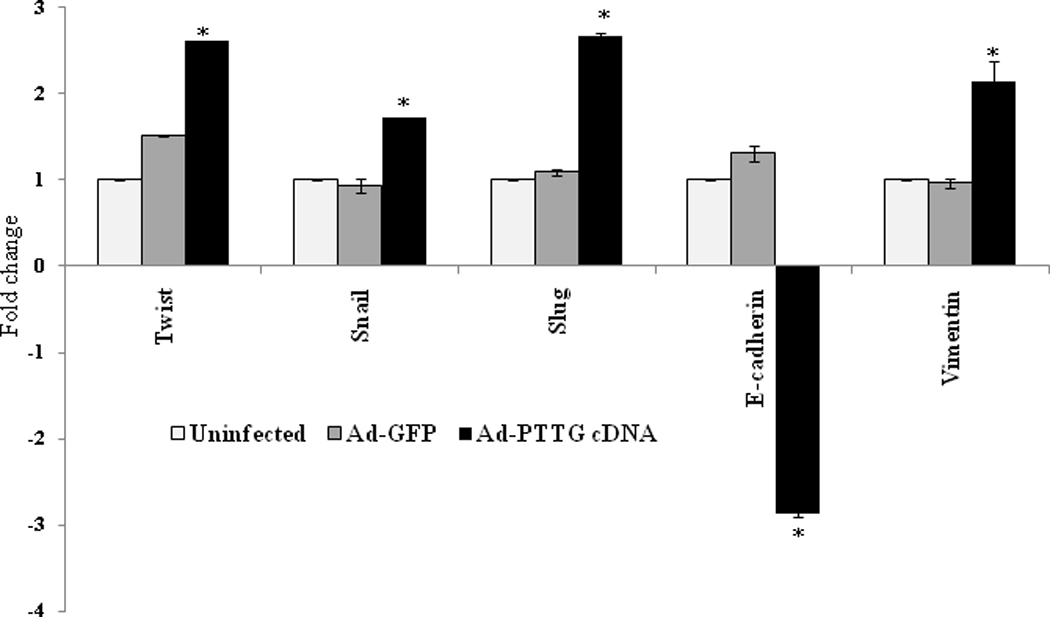

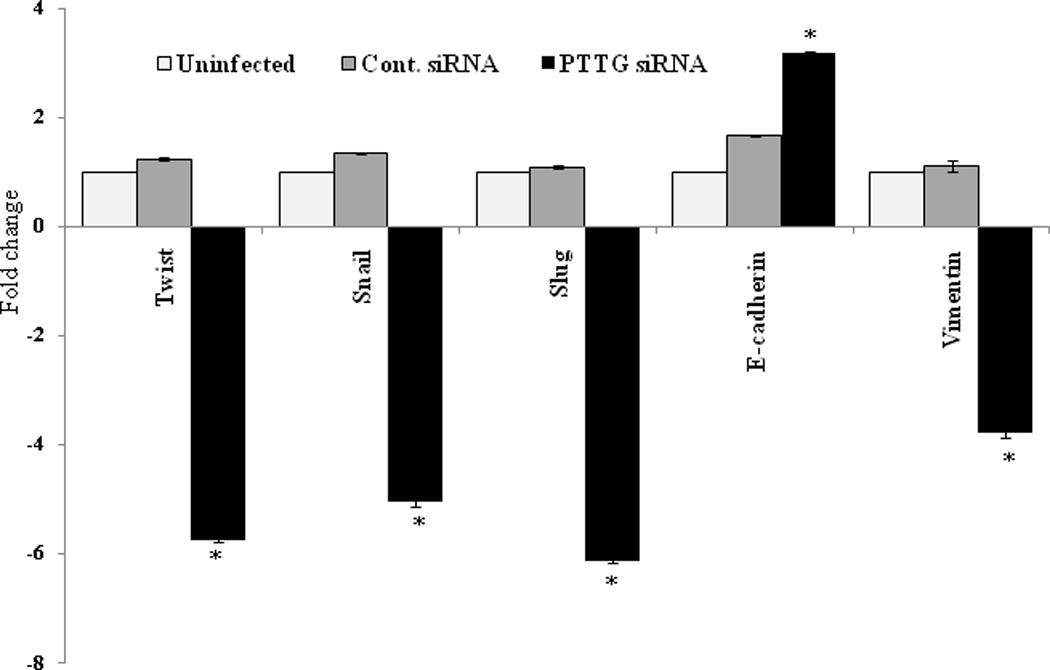

Loss of E-cadherin gene expression is frequently found during tumor progression in most epithelial cancers. Therefore, loss of E-cadherin function is a critical indicator for poor prognosis and metastasis. E-cadherin expression is regulated by multiple factors. At the transcriptional level, Twist, Snail and Slug have been reported to repress E-cadherin expression leading to induction of EMT [26]. To determine the effect of PTTG on expression of Twist, Snail, Slug, vimentin and E-cadherin, we overexpressed PTTG in A2780 by infecting the cells with Ad-PTTG cDNA. Levels of expression of these genes were analyzed using quantitative real-time PCR. As shown in Fig. 4, infection of A2780 cells with Ad-PTTG cDNA resulted in a significant increase in the expression of Twist, Snail and Slug (2.6, 1.7 and 2.6-fold, respectively) compared to uninfected cells or cells infected with control Ad-GFP. Loss of E-cadherin and gain of vimentin are reported to serve as markers for the induction of EMT [16]. Infection of cells with Ad-PTTG cDNA showed up-regulation of vimentin mRNA and down regulation of E-cadherin mRNA (Fig. 4). Loss of E-cadherin expression and gain of vimentin by PTTG was further confirmed by immunohistochemical analysis of E-cadherin and vimentin that showed a significant reduction of E-cadherin specific staining in A2780 cells compared to uninfected cells (Fig. 5A), and a significant increase in vimentin specific staining compared to uninfected cells (Fig. 5B). To confirm our results and to determine if down-regulation of PTTG expression can reverse the effects, we performed knockout experiments by infecting A2780 cells with Ad-PTTG siRNA. As shown in Fig. 6, down-regulation of PTTG expression in A2780 cells resulted in a significant suppression of Twist, Snail, and Slug expression (5.7-, 5.0-, and 6.1-fold, respectively). E-cadherin was significantly up-regulated (3.2-fold) whereas vimentin was significantly down regulated (3.8-fold) in cells infected with Ad-PTTG siRNA compared to uninfected cells or cells infected with control Ad-siRNA.

Figure 4.

Regulation of expression of Twist, Snail, Slug, E-cadherin and vimentin by PTTG. Cells were infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-PTTG cDNA, expression of Twist, Snail, Slug, E-cadherin and vimentin was analyzed by using quantitative real-time PCR. Values were normalized with GAPDH used as an internal control. Columns, mean (n = 3); bars, SEM. *P < 0.05.

Figure 5.

Fluorescence microscopy of A2780 cells. A: i and ii, uninfected cells. iii and iv, cells infected with Ad-PTTG cDNA. i and iii, E-cadherin was detected using Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated secondary goat anti-mouse antibody. ii and iv, double staining of cells with Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated secondary goat anti-mouse antibody for E-cadherin and DAPI for nuclei. Calibration bar in the right panels is 20 µM. B: i and ii, uninfected cells. iii and iv, cells infected with Ad-PTTG cDNA. i and iii, vimentin was detected using Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated secondary goat anti-mouse antibody. ii and iv, double staining with Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated secondary goat anti-mouse antibody for vimentin and DAPI for nuclei. Calibration bar in the right panels is 20 µM.

Figure 6.

Regulation of expression of Twist, Snail, Slug, E-cadherin and vimentin in A2780 cells. Cells were infected with Ad-PTTG siRNA or control Ad-siRNA. Expression of Twist, Snail, Slung, E-cadherin and vimentin was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR. Values were normalized with GAPDH used as an internal control. Columns, mean (n = 3); bars, SEM. *P < 0.05.

Taken together our results clearly suggest that PTTG induces EMT in ovarian epithelial tumor cells through the up-regulation of Twist, Snail, and Slug, accompanied by the loss of EMT marker E-cadherin, and gain of mesenchymal marker vimentin.

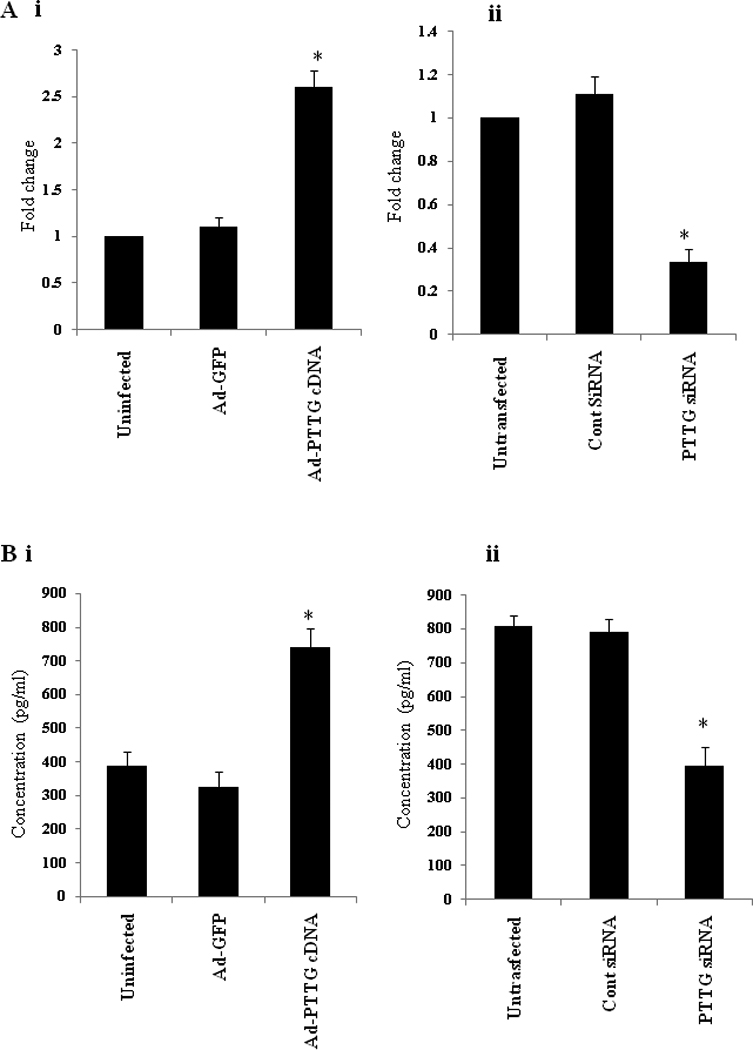

3.3 PTTG increases TGF-β mRNA expression and secretion leading to induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition

The TGF-β pathway has been studied in many metastatic processes prior to tumor cells spreading throughout the body [24]. To determine the mechanism by which PTTG regulates the induction of EMT, we determined the levels of TGF-β mRNA in cells infected with Ad-PTTG cDNA or Ad-PTTG siRNA and secretion of TGF-β in conditioned culture medium from A2780 cells infected with Ad-PTTG cDNA or Ad-PTTG siRNA. As shown in Fig. 7 i, A2780 cells infected with Ad-PTTG cDNA showed a significantly higher level (2.6-fold) of TGF-β mRNA expression compared to cells infected with Ad-GFP or uninfected cells. In contrast, cells infected with Ad-PTTG siRNA showed significantly decrease in level (0.3-fold) of TGF-β mRNA expression compared to cells infected with control Ad-siRNA or uninfected cells (Fig. 7 ii). Measurement of TGF-β secretion in medium after infecting cells with Ad-PTTG cDNA or Ad-GFP and Ad-PTTG siRNA or control Ad-siRNA, showed significant increase in level of TGF-β in medium collected from A2780 cells infected with Ad-PTTG cDNA (Fig. 7B i) compared to cells infected with Ad-GFP or uninfected cells. Interestingly, cells infected with PTTG siRNA showed significantly lower level of TGF-β in the medium compared to cells infected with control siRNA or uninfected cells (Fig. 7 B ii).

Figure 7.

Expression and secretion of TGF-β in A2780 cells infected with Ad-PTTG cDNA, Ad-GFP or Ad-control siRNA or Ad-PTTG siRNA. A: i, mRNA expression of TGF-β in A2780 cells infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-PTTG cDNA. ii, mRNA expression of TGF-β in A2780 cells infected with Ad-control siRNA or Ad-PTTG siRNA. B: Measurement of secretion of TGF-β in conditioned medium. i, cells infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-PTTG cDNA. ii, cells infected with Ad-PTTG siRNA or Ad-control siRNA. Columns, mean (n = 3); bars, SEM. *P < 0.05.

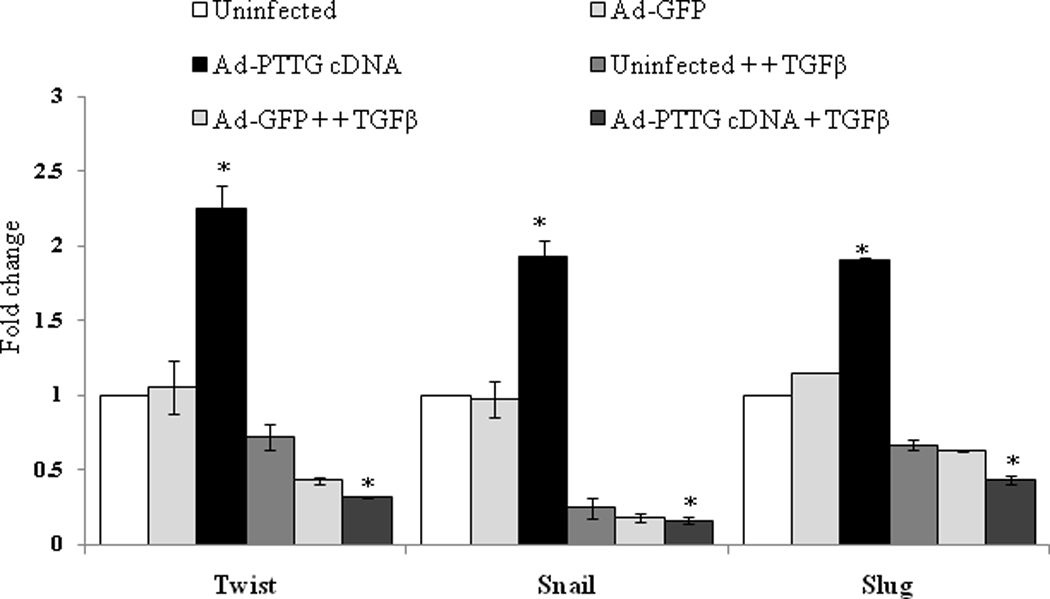

3.4. Blocking of TGF-beta down regulates the expression of Twist, Snail, and Slug

To confirm that the up-regulation of Twist, Snail and Slug by PTTG is mediated through the regulation of TGF-b, we blocked TGF-b by using TGF-b neutralizing antibody and examined the effect of PTTG on Twist, Snail and Slug expression. As shown in Fig. 8, infection of A2780 cells with Ad-PTTG cDNA resulted in a significant increase in the expression of Twist, Snail and Slug compared to uninfected cells or cells infected with control Ad-GFP. Blocking of TGF-b with TGFb neutralizing antibody resulted in a complete blockage of expression of Twist, Snail and Slug induced by PTTG, indicating the important role of TGF-b in mediating the regulation of Twist, Snail and Slug by PTTG resulting in induction of EMT.

Figure 8.

Effect of blocking of TGF-b by neutralizing antibody. A2780 cells were infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-PTTG cDNA. After 24 h of infection, cells were treated with TGF-b neutralizing antibody. After 48 h of treatment of cells with antibody, expression of Twist, Snail and Slug was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR. Values were normalized with GAPDH used as an internal control. Columns, mean (n = 3); bars, SEM. *P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

EMT is an essential step in tumor progression and metastasis. The various steps involved in tumor progression and metastasis include detachment of tumor cells from primary tumor site, attachment and invasion at distant sites, followed by subsequent growth. These steps require a transcriptional reprogramming that are characterized by the combined loss of epithelial cell-junction proteins and cell polarity, including loss of epithelial marker, E-cadherin, the gain of mesenchymal markers such as vimentin and fibronectin mobility, invasiveness of tumor cells, and increase in angiogenesis [20].

PTTG has been identified as an oncogene [2,3,7]. Its over expression has been reported in various cancers including ovarian cancer reviewed in [6]. Over expression of PTTG has been reported to increase cell proliferation, induce cellular transformation, and promote tumorigenesis in nude mice [2,7,8]. In vivo, Melmed and his colleagues [33] showed that over expression of PTTG in the pituitary of transgenic animals using the α-GSU promoter leads to enlargement of the pituitary, development of pituitary adenomas, and hyperplasia of the prostate. In our studies using mullerin inhibitory substance type II receptor (MISIIR) gene promoter to target PTTG expression in ovary, we observed enlargement of ovaries, cystic glandular hyperplasia of the myometrium, and hyperplasia of the endometrium, suggesting development of precancerous conditions by PTTG [34]. Levels of PTTG expression correlate with stage of tumorigenesis, angiogenesis, and metastasis [11,12]. EMT is an important process in tumor progression and metastasis. To define the role of PTTG in regulation of EMT, we determined the mechanism for the regulation of expression of E-cadherin. As shown in Fig.4, infection of A2780 cells with PTTG cDNA resulted in down-regulation of expression of epithelial marker, E-cadherin, and up-regulation of mesenchymal marker, vimentin. Induction of EMT by PTTG was further confirmed by morphological analysis of the cells infected with Ad-PTTG cDNA, which showed morphological changes from flat and elongated to circular and spherical with the appearance of lamellipodia and filopodia (Fig. 3), which are indicative of invasiveness [35].

Twist, Snail, and Slug serve as transcription repressors for the expression of E-cadherin. Loss of E-cadherin expression has been shown to be key event of EMT, which is induced by slug and Snail [36]. Twist, a transcription factor containing a helix-loop-helix DNA binding domain, is known to trigger EMT by initiation of N-cadherin expression in Drosophila [37]. Twist is also shown to be up-regulated in several types of epithelial cancers, including breast, prostate, and gastric carcinomas [38–40]. Terauchi et al. [41] demonstrated that the suppression of Twist expression alters cellular morphology and inhibits migration in ovarian cancer cells in vitro. Snail has been shown to be a strong repressor of transcription of the E-cadherin gene and evokes tumorigenic and invasive properties in epithelial cells upon overexpression [19]. Kurrey et al. [42] reported that the ectopic expression of Snail resulted in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and enhanced motility and invasiveness. High expressions of Snail and Slug are often found in metastatic ovarian tumor cells compared with primary tumors [43]. Inverse correlation of Snail and E-cadherin was detected in hepatocellular carcinoma-derived cell lines [44], in oral squamous cell carcinomas [45], and human primary melanocytes [46]. Examination of expression of Twist, Snail, and Slug in A2780 cells with Ad-PTTG cDNA infection revealed a significant increase in the expression of Twist, Snail, and Slug, leading to loss of E-cadherin resulting in the induction of EMT. These results are consistent with the mechanism of induction of EMT. Overexpression of vimentin by PTTG further confirms the induction of EMT by PTTG.

In our previous studies, we showed that down-regulation of PTTG expression in ovarian tumor cell line A2780 or lung cancer cell line H1299 inhibits cell proliferation, cellular transformation, and tumor development in nude mice [30,32]. Mice lacking PTTG are viable and fertile, but showed diminished pancreatic β-cell mass, with impaired glucose homeostasis leading to diabetes during late adulthood, suggesting a defect in β-cell division [47]. Cross breeding of PTTG (−/−) and Rb (+/−) animals results in a reduction of tumor development from 86% in Rb (+/−)/PTTG (+/+) to 30% in Rb (+/−)/PTTG (−/−) animals. In addition, Rb (+/−)/PTTG (−/−) animals showed pituitary hypoplasia associated with suppression of cell proliferation and a prevention of high penetrance of pituitary tumors in Rb+/− animals, suggesting a requirement of PTTG in tumor development and its prevention upon loss of PTTG [48]. To determine if down-regulation of PTTG prevents the induction of EMT by down-regulating the genes responsible for the induction of EMT, we infected A2780 cells with Ad-PTTG siRNA and adenovirus carrying control siRNA. Our results showed down-regulation in the expression of Twist, Snail, and Slug, and up-regulation of EMT marker E-cadherin in A2780 cells infected with Ad-PTTG siRNA compared to uninfected cells or cells infected with control siRNA (Fig.6). In contrast mesenchymal marker vimentin was downregulated (Fig. 6). Taken together our results suggest PTTG induces EMT by down-regulating the expression of E-cadherin mediated by Twist, Snail, and Slug, which are up-regulated by PTTG.

Increased TGF-β1 expression by tumor cells has been correlated with tumor progression in non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, and gastric carcinoma [49–51]. In our experiments, we showed an increase in TGF-β mRNA as well secretion in A2780 cells infected with Ad-PTTG cDNA compared to uninfected cells or cells infected with Ad-GFP (Fig. 7A i and 7B i). On the other hand, downregulation of PTTG by using PTTG siRNA resulted in decrease in mRNA and secretion of TGF-β compared to uninfected cells or cells infected with control siRNA (Fig. 7A ii and 7B ii). Blocking of TGF-β by neutralizing antibody resulted in a complete blockage of expression of Twist, Snail and Slug induced by PTTG, indicating the role of PTTG in induction of EMT through the regulation of TGF-β. TGF-β has long been known to be a major inducer of EMT, particularly in heart formation and palate fusion in mice, as well as in some mammary cell lines, and in mouse models of skin carcinogenesis [22,23]. Do et al. [52] showed that TGF-β at 10 ng/ml induced a fibroblast-like morphological change of OVCA429 cells, suggesting that TGF-β at higher concentrations is able to induce morphological change of EOC cells. During EMT, cell-to-cell junctions are disrupted, the actin cytoskeleton is extensively reorganized, and the cells acquire increased migratory characteristics which changes their morphology. These characteristics of EMT by TGF-β are consistent with those of PTTG whose increase in expression results in changes in the morphology of cells. During TGF-β-mediated EMT, E-cadherin expression is decreased while vimentin expression is increased [24,53]. These results are consistent with our present study: up-regulation of PTTG results in the significant decrease in E-cadherin and increase in vimentin expression, indicating a step towards EMT (Figs. 4 and 5). Recent work has identified that TGF-β signaling through Smad-mediated expression of high mobility group A2 (HMGA2) is an important for the induction of Snail and Slug, which are zinc-finger transcription factors known to repress the E-cadherin gene [54]. In our present study, we showed that increase in expression of PTTG in A2780 cells increases the expression of TGF-β (Fig. 7), suggesting that PTTG induces EMT through the regulation of TGF-β expression and secretion in ovarian cancer cells.

Conclusions

Our results suggest for the first time an important role of PTTG in induction of EMT by regulating TGF-β expression and secretion that results in regulating the expression of E-cadherin through the regulation of E-cadherin transcription repressor genes Twist, Snail, and Slug. (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Schematic presentation of regulation of EMT by PTTG.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by a grant from NCI CA 124630 (SSK).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

None

Contributor Information

Parag P. Shah, Email: ppshah04@louisville.edu.

Sham S. Kakar, Email: sskaka01@louisville.edu.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer Statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pei L, Melmed S. Isolation and characterization of a pituitary tumor-transforming gene (PTTG) Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:433–441. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.4.9911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang X, Horwitz GA, Prezant TR, Valentini A, Nakashima M, Bronstein MD, Melmed S. Structure, expression, and function of human pituitary tumor-transforming gene (PTTG) Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:156–166. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.1.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee IA, Seong C, Choe IS. Cloning and expression of human cDNA encoding human homologue of pituitary tumor transforming gene. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1999;47:891–897. doi: 10.1080/15216549900201993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kakar SS, Jennes L. Molecular cloning and characterization of the tumor transforming gene (TUTR1): a novel gene in human tumorigenesis. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1999;84:211–216. doi: 10.1159/000015261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panguluri SK, Yeakel C, Kakar SS. PTTG: an important target gene for ovarian cancer therapy. J Ovarian Res. 2008;1:6. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kakar SS. Molecular cloning, genomic organization, and identification of the promoter for the human pituitary tumor transforming gene (PTTG) Gene. 1999;240:317–324. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00446-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamid T, Malik MT, Kakar SS. Ectopic expression of PTTG1/securin promotes tumorigenesis in human embryonic kidney cells. Mol Cancer. 2005;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zou H, McGarry TJ, Bernal T, Kirschner MW. Identification of a vertebrate sister-chromatid separation inhibitor involved in transformation and tumorigenesis. Science. 1999;285:418–422. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5426.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Z, Yu R, Melmed S. Mice lacking pituitary tumor transforming gene show testicular and splenic hypoplasia, thymic hyperplasia, thrombocytopenia, aberrant cell cycle progression, and premature centromere division. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1870–1879. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.11.0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishikawa H, Heaney AP, Yu R, Horwitz GA, Melmed S. Human pituitary tumor-transforming gene induces angiogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:867–874. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCabe CJ, Boelaert K, Tannahill LA, Heaney AP, Stratford AL, Khaira JS, Hussain S, Sheppard MC, Franklyn JA, Gittoes NJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor, its receptor KDR/Flk-1, and pituitary tumor transforming gene in pituitary tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4238–4244. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamashita S, Miyagi C, Fukada T, Kagara N, Che YS, Hirano T. Zinc transporter LIVI controls epithelial-mesenchymal transition in zebrafish gastrula organizer. Nature. 2004;429:298.N–302.N. doi: 10.1038/nature02545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed, Thompson EW, Quinn MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal interconversions in normal ovarian surface epithelium and ovarian carcinomas: an exception to the norm. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:581–588. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vergara D, Merlot B, Lucot JP, Collinet P, Vinatier D, Fournier I, Salzet M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in ovarian cancer. Cancer Lett. 291:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmalhofer O, Brabletz S, Brabletz T. E-cadherin, beta-catenin, and ZEB1 in malignant progression of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:151–166. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9179-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karreth F, Tuveson DA. Twist induces an epithelial-mesenchymal transition to facilitate tumor metastasis. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:1058–1059. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.11.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Batlle E, Sancho E, Franci C, Dominguez D, Monfar M, Baulida J, Garcia De Herreros A. The transcription factor snail is a repressor of E-cadherin gene expression in epithelial tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:84–89. doi: 10.1038/35000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cano A, Perez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, Portillo F, Nieto MA. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83. doi: 10.1038/35000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno-Bueno G, Cubillo E, Sarrio D, Peinado H, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Villa S, Bolos V, Jorda M, Fabra A, Portillo F, Palacios J, Cano A. Genetic profiling of epithelial cells expressing E-cadherin repressors reveals a distinct role for Snail, Slug, and E47 factors in epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9543–9556. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander NR, Tran NL, Rekapally H, Summers CE, Glackin C, Heimark RL. N-cadherin gene expression in prostate carcinoma is modulated by integrin-dependent nuclear translocation of Twist1. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3365–3369. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derynck R, Akhurst RJ. Differentiation plasticity regulated by TGF-beta family proteins in development and disease. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1000–1004. doi: 10.1038/ncb434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhowmick NA, Neilson EG, Moses HL. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression. Nature. 2004;432:332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature03096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murakami M, Suzuki M, Nishino Y, Funaba M. Regulatory expression of genes related to metastasis by TGF-beta and activin A in B16 murine melanoma cells. Mol Biol Rep. 37:1279–1286. doi: 10.1007/s11033-009-9502-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitagawa K, Murata A, Matsuura N, Tohya K, Takaichi S, Monden M, Inoue M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transformation of a newly established cell line from ovarian adenosarcoma by transforming growth factor-beta1. Int J Cancer. 1996;66:91–97. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960328)66:1<91::AID-IJC16>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piek E, Moustakas A, Kurisaki A, Heldin CH, ten Dijke P. TGF-(beta) type I receptor/ALK-5 and Smad proteins mediate epithelial to mesenchymal transdifferentiation in NMuMG breast epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 24):4557–4568. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.24.4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keshamouni VG, Michailidis G, Grasso CS, Anthwal S, Strahler JR, Walker A, Arenberg DA, Reddy RC, Akulapalli S, Thannickal VJ, Standiford TJ, Andrews PC, Omenn GS. Differential protein expression profiling by iTRAQ-2DLC-MS/MS of lung cancer cells undergoing epithelial-mesenchymal transition reveals a migratory/invasive phenotype. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:1143–1154. doi: 10.1021/pr050455t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kakar SS, Malik MT. Suppression of lung cancer with siRNA targeting PTTG. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:387–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panguluri SK, Kakar SS. Effect of PTTG on endogenous gene expression in HEK 293 cells. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:577. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Naggar SM, Malik MT, Kakar SS. Small interfering RNA against PTTG: a novel therapy for ovarian cancer. Int J Oncol. 2007;31:137–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbud RA, Takumi I, Barker EM, Ren SG, Chen DY, Wawrowsky K, Melmed S. Early multipotential pituitary focal hyperplasia in the alpha-subunit of glycoprotein hormone-driven pituitary tumor-transforming gene transgenic mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1383–1391. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El-Naggar SM, Malik MT, Martin A, Moore JP, Proctor M, Hamid T, Kakar SS. Development of cystic glandular hyperplasia of the endometrium in Mullerian inhibitory substance type II receptor-pituitary tumor transforming gene transgenic mice. J Endocrinol. 2007;194:179–191. doi: 10.1677/JOE-06-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yilmaz M, Christofori G. EMT, the cytoskeleton, and cancer cell invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:15–33. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thiery JP, Sleeman JP. Complex networks orchestrate epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:131–142. doi: 10.1038/nrm1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oda H, Tsukita S, Takeichi M. Dynamic behavior of the cadherin-based cell-cell adhesion system during Drosophila gastrulation. Dev Biol. 1998;203:435–450. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosivatz E, Becker I, Specht K, Fricke E, Luber B, Busch R, Hofler H, Becker KF. Differential expression of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition regulators snail, SIP1, and twist in gastric cancer. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1881–1891. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64464-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watanabe O, Imamura H, Shimizu T, Kinoshita J, Okabe T, Hirano A, Yoshimatsu K, Konno S, Aiba M, Ogawa K. Expression of twist and wnt in human breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:3851–3856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwok WK, Ling MT, Lee TW, Lau TC, Zhou C, Zhang X, Chua CW, Chan KW, Chan FL, Glackin C, Wong YC, Wang X. Up-regulation of TWIST in prostate cancer and its implication as a therapeutic target. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5153–5162. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terauchi M, Kajiyama H, Yamashita M, Kato M, Tsukamoto H, Umezu T, Hosono S, Yamamoto E, Shibata K, Ino K, Nawa A, Nagasaka T, Kikkawa F. Possible involvement of TWIST in enhanced peritoneal metastasis of epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2007;24:329–339. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kurrey NK, K A, Bapat SA. Snail and Slug are major determinants of ovarian cancer invasiveness at the transcription level. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elloul S, Silins I, Trope CG, Benshushan A, Davidson B, Reich R. Expression of E-cadherin transcriptional regulators in ovarian carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:520–528. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiao W, Miyazaki K, Kitajima Y. Inverse correlation between E-cadherin and Snail expression in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:98–101. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yokoyama K, Kamata N, Hayashi E, Hoteiya T, Ueda N, Fujimoto R, Nagayama M. Reverse correlation of E-cadherin and snail expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells in vitro. Oral Oncol. 2001;37:65–71. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poser I, Dominguez D, de Herreros AG, Varnai A, Buettner R, Bosserhoff AK. Loss of E-cadherin expression in melanoma cells involves up-regulation of the transcriptional repressor Snail. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24661–24666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011224200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Z, Moro E, Kovacs K, Yu R, Melmed S. Pituitary tumor transforming gene-null male mice exhibit impaired pancreatic beta cell proliferation and diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3428–3432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0638052100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chesnokova V, Kovacs K, Castro AV, Zonis S, Melmed S. Pituitary hypoplasia in Pttg−/− mice is protective for Rb+/− pituitary tumorigenesis. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2371–2379. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hasegawa Y, Takanashi S, Kanehira Y, Tsushima T, Imai T, Okumura K. Transforming growth factor-beta1 level correlates with angiogenesis, tumor progression, and prognosis in patients with nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;91:964–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saito H, Tsujitani S, Oka S, Kondo A, Ikeguchi M, Maeta M, Kaibara N. The expression of transforming growth factor-beta1 is significantly correlated with the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and poor prognosis of patients with advanced gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86:1455–1462. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991015)86:8<1455::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsushima H, Kawata S, Tamura S, Ito N, Shirai Y, Kiso S, Imai Y, Shimomukai H, Nomura Y, Matsuda Y, Matsuzawa Y. High levels of transforming growth factor beta 1 in patients with colorectal cancer: association with disease progression. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:375–382. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8566583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Do TV, Kubba LA, Du H, Sturgis CD, Woodruff TK. Transforming growth factor-beta1, transforming growth factor-beta2, and transforming growth factor-beta3 enhance ovarian cancer metastatic potential by inducing a Smad3-dependent epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:695–705. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grande M, Franzen A, Karlsson JO, Ericson LE, Heldin NE, Nilsson M. Transforming growth factor-beta and epidermal growth factor synergistically stimulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) through a MEK-dependent mechanism in primary cultured pig thyrocytes. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4227–4236. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siegel PM, Shu W, Cardiff RD, Muller WJ, Massague J. Transforming growth factor beta signaling impairs Neu-induced mammary tumorigenesis while promoting pulmonary metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8430–8435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932636100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]