Background: Cathepsins participate to the release of endostatin, a potent anti-angiogenic protein.

Results: Both cathepsins L and S generate two peptides from human endostatin with increased angiostatic properties.

Conclusion: Endostatin-derived peptides reduce tube formation of endothelial cells.

Significance: Endostatin-derived peptides may represent novel molecular links between cysteine cathepsins and aminopeptidase N in the regulation of angiogenesis.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Cysteine Protease, Endothelial Cell, Protein Degradation, Proteolytic Enzymes, Aminopeptidase N, Cathepsin, Collagen XVIII, Endostatin, NGR Motif

Abstract

Human endostatin, a potent anti-angiogenic protein, is generated by release of the C terminus of collagen XVIII. Here, we propose that cysteine cathepsins are involved in both the liberation and activation of bioactive endostatin fragments, thus regulating their anti-angiogenic properties. Cathepsins B, S, and L efficiently cleaved in vitro FRET peptides that encompass the hinge region corresponding to the N terminus of endostatin. However, in human umbilical vein endothelial cell-based assays, silencing of cathepsins S and L, but not cathepsin B, impaired the generation of the ∼22-kDa endostatin species. Moreover, cathepsins L and S released two peptides from endostatin with increased angiostatic properties and both encompassing the NGR sequence, a vasculature homing motif. The G10T peptide (residues 1455–1464: collagen XVIII numbering) displayed compelling anti-proliferative (EC50 = 0.23 nm) and proapoptotic properties. G10T inhibited aminopeptidase N (APN/CD13) and reduced tube formation of endothelial cells in a manner similar to bestatin. Combination of G10T with bestatin resulted in no further increase in anti-angiogenic activity. Taken together, these data suggest that endostatin-derived peptides may represent novel molecular links between cathepsins and APN/CD13 in the regulation of angiogenesis.

Introduction

Endostatin, first discovered by Folkman and collaborators (1), is a potent therapeutic agent through its ability to inhibit the formation of new blood vessels and reduce tumor growth as a single drug or in combination with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy (2, 3). Endostatin, which corresponds to the C-terminal domain of collagen XVIII (NC-1 domain), is released by cleavage of a proteolysis-sensitive unstructured hinge region. Endostatin prevents the proliferation, migration, and adhesion of endothelial cells, blocks cell intravasation, and may also induce apoptosis (4–6). Inhibition of the migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)3 occurs in response to VEGF (7). The various effects that endostatin elicits on cells is indicative of its multiple modes of action and molecular partners (e.g. integrin αVβ3 and integrin α5β1, glypicans, heparin and heparan sulfates) that form the so-called “endostatin interaction network” (8).

Alterations in endostatin levels that are frequently observed in pathophysiological processes are of crucial importance. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanisms involved in the production and catabolism of endostatin remains poorly characterized. Although endostatin is generally described as a single protein of ∼20 kDa, several forms of varying lengths have been identified in vivo in both humans and mice (9). The first protease identified as responsible for the release of murine endostatin (20-kDa form) was cathepsin L (10). Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) have also been implicated in the release of high molecular mass endostatin forms (24–30 kDa) (11). Despite high primary structural identity in collagen XVIII between human and mice, their hinge regions display some critical differences in their amino acid sequences (9, 12). Consequently, the proteases involved in the release of human endostatin from collagen XVIII have not been clearly identified.

The aim of this study was to delineate the role of cysteine cathepsins in the production and/or degradation of human collagen XVIII-derived endostatin and to analyze the consequences in its anti-angiogenic properties on endothelial cells. Our results suggest that cathepsins may finely tune release and breakdown of endostatin and give new molecular insights into its angiogenic mechanisms. These data also advocate that through endostatin-derived peptides, cysteine cathepsins and aminopeptidase N (APN/CD13) may both participate in the multidirectional network of proteolytic interactions that occur during angiogenesis (13).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Enzymes, Inhibitors, and Peptides

Human cathepsins B, L, H, and S were from Calbiochem (VWR Intl., Libourne, France). Aminopeptidase N was from R&D Systems Europe (Lille, France). Bestatin, l-trans-epoxysuccinyl-leucylamido-(4-guanidio)butane (E-64), N-(l-3-trans-propylcarbomoyl-oxirane-2-carbonyl)-l-isoleucyl-l-proline (CA-074), methylmethanethiosulfonate, pepstatin A, and PMSF were from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Quentin Fallavier, France). EDTA was from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Ac-DEVD-FMK (FMK, fluoromethyl ketone) was from Calbiochem, and bestatin was R&D Systems Europe. DTT was from Bachem (Weil am Rhein, Germany). Z-FR-AMC, Z-GPR-AMC, Z-LR-AMC, H-R-AMC, and Ac-DEVD-AMC were from Calbiochem, whereas H-A-AMC was supplied by Bachem. Cathepsins were titrated by E-64 in their activity buffer (0.1 m sodium acetate, pH 5.5, 2 mm EDTA, 2 mm DTT, and Brij 35 0.01%). FRET peptides (Endo-01 to Endo-10) were prepared as described previously (14). G10T (GSDPNGRRLT), Sc-G10T (i.e. scrambled G10T; GNPTDLRSRG), and K15T (KSVWHGSDPNGRRLT) peptides were synthesized by Eurogentec SA (Seraing, Belgium).

Kinetics Measurement

The hydrolysis of Endo-01 to Endo-10 substrates was followed by measuring fluorescence release (Kontron SFM 25 spectrofluorimeter; excitation wavelength, 320 nm; emission wavelength, 420 nm). The system was formerly standardized using Abz-FR-OH prepared by the total tryptic hydrolysis of an Abz-FR-pNA solution, with ϵ410 nm = 8,800 m−1 cm−1 for p-nitroanilide as reported previously (15). Final enzyme concentrations were 1–5 nm for cathepsins L and S, 5–10 nm for cathepsin B, and 10–100 nm for cathepsin H. Assays (triplicate) were carried out at 37 °C by adding cathepsins to intramolecularly quenched fluorescent peptides (0.5 μm) in their activity buffer. Second-order rate constants (kcat/Km) for the hydrolysis of Endo-01 to Endo-10 were determined under pseudo-first order conditions, i.e. using a substrate concentration far below the Km). Under these conditions, the Michaelis-Menten equation is reduced to: v = kobs·S, where kobs = Vm/Km. Integrating this equation over time gives ln [S] = −kobs·t + ln[S]0, where [S]0 and [S] are the substrate concentrations at time 0 and time t, respectively. Because Vm = kcat·[E]t, where [E]t is the final enzyme concentration, dividing kobs by [E]t yields the kcat/Km ratio. The kobs for the first-order substrate hydrolysis was calculated by fitting experimental data to the first-order equation using the Enzfitter software (Biosoft, Cambridge, UK). Kinetics data (i.e. specificity constants) are reported as means ± S.D. Additionally, enzymes (10 nm) were incubated with peptides (100 μm) for 60 min at 37 °C in the assay buffer before RP-HPLC analysis (Purospher star RP18 column, Merck) using a 20-min linear (0–60%) gradient of acetonitrile in 0.1% TFA (λ = 220 nm). Cleavage sites were identified by mass spectrometry (Valérie Labas, Proteomics Facilities, Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique Tours).

Degradation of Human Endostatin by Cysteine Cathepsins

Recombinant human endostatin (1 mm, Sigma-Aldrich) was incubated for 4 h at 37 °C in 0.1 m sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.5, 2 mm DTT in the presence of proteases (enzyme/substrate molar ratio, 1:200 to 1:5). Hydrolysis products were separated by RP-HPLC (Purospher star RP8 column, Merck) using a 35-min linear (0–60%) gradient of acetonitrile in 0.1% TFA and analyzed by mass spectrometry. In parallel samples were submitted to a 15% SDS-PAGE then electroblotted. The nitrocellulose membrane was incubated with a rabbit anti-endostatin antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) (dilution of 1:1000) and then with a anti-rabbit IgG-peroxidase conjugate (Sigma-Aldrich) (dilution: 1: 5000) and revealed (ECL kit from Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). In addition, endostatin was incubated with cathepsins (enzyme/substrate ratio of 1:10) for 0–120 min, and samples were analyzed by 15% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue, and the level of uncleaved residual endostatin was estimated by densitometry (NIH ImageJ software). Control was performed in the presence of E-64 (10 mm).

Silencing of Cathepsins B, L, and S by RNA Interference

HUVECs (PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany) were grown in endothelial cell growth medium, containing 2% FCS at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Small interfering RNAs for cathepsin L (siCatL), cathepsin S (siCatS), cathepsin B (siCatB), and a negative control siRNA (siCTL) were obtained from Qiagen SA (Courtaboeuf, France) (Table 1). At 80% confluence, cells were transfected with 40 nm siRNA in endothelial basal medium using HiPerFect transfection agent (Qiagen SA). Total RNAs were extracted at different times (24, 48, 72, and 96 h) (RNeasy Mini Kit, Qiagen SA), and reverse transcription was performed on total RNA (1 mg) using RevertAid M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (GmbH, Germany). Reduction of cathepsins transcripts was determined by quantitative real-time PCR using the MyiQ system (Bio-Rad) in the presence of SyberGreen Mix (ABgene, Epsom, UK). Sense and antisense primers for cathepsins were reported in Table 1. For quantification of relative expression levels, the ΔΔCt method was used (normalization gene, human ribosomal protein S16 (RPS16)).

TABLE 1.

siRNA sequences and primers used for quantitative PCR experiments

Cat, cathepsin.

| Protein | Sequences of siRNA (5′–3′) | Sequences of PCR primers (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Cat S | ||

| Sense | GGAUAUAUUCGGAUGGCAA | GCTTCACAACCTGGAGCATTC |

| Antisense | UUGCCAUCCGAAUAUAUCC | GGCAATATCCGATTAGGGTTTGA |

| Cat L | ||

| Sense | GAUCCGAGUGUGAUUUGAA | GGAAAACTGGGAGGCTTATCTC |

| Antisense | UUCAAUCACACUCGGAUC | AGCATAATCCATTAGGCCACCA |

| Cat B | ||

| Sense | GCAUGAUUCUUUAAUAGAA | AGAGTTATGTTTACCGAGGACCT |

| Antisense | UUCUAUUAAAGAAUCAUGC | GCAGATCCGGTCAGAGATGG |

| RPS16 | ||

| Sense | ACGTGGCCCAGATTTATGCTAT | |

| Antisense | TGGAAGCCTCATCCACATATTTC |

At various post-transfection times, cells were rinsed in PBS, lysed (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, Nonidet P40 1% in the presence of 100 μm E-64, 0.5 mm PMSF, 40 μm pepstatin A, and 0.5 mm EDTA) and centrifuged, and the protein concentration was measured (BCA protein assay kit, Interchim, Montluçon, France). Following running by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, Western blots were accomplished as described earlier using rabbit polyclonal antibodies (dilution of 1:1000) directed, respectively, against endostatin (Abcam), cathepsin L, cathepsin S, and cathepsin B (Calbiochem). Furthermore, proteolytic activities of cathepsins were measured at 37 °C in both supernatants and cell lysates. Assays were performed in 0.1 m sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.5, 2 mm DTT, 2 mm EDTA, using Z-FR-AMC (50 mm) as a substrate for both cathepsins B and L and Z-LR-AMC (50 mm) as a preferred substrate for cathepsins S and K (Spectramax Gemini, Molecular Devices; excitation wavelength = 350 nm, emission wavelength = 460 nm) (16). Assay for specific cathepsin K activity was achieved by using Z-GPR-AMC (50 μm) in the presence of CA-074. Alternatively, because only cathepsin S retains its proteolytic activity under mildly alkaline conditions, sample was incubated in a 100 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, for 1 h at 37 °C before the residual specific activity of cathepsin S was measured using Z-LR-AMC (50 μm). Overall cathepsin activity was determined by E-64 titration, whereas cathepsin B was titrated by CA-074.

Cell Culture

Proliferation Assays

HUVEC cells were seeded in a 96-well plate (10,000 cells/well) for 24 h in complete medium before adding VEGF (20 ng/ml) in basal medium (PromoCell). Moreover, either 0.1 mm endostatin, 0.1 mm hydrolysis products, or peptides G10T and K15T (10−14 to 10−7 m) were combined to the medium in the presence of 20 mm E-64. 24 h later, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (Promega) was added (20 ml/well), and absorbance was measured after a 2-h incubation (l = 490 nm; Thermomax microplate reader, Molecular Devices). Correspondingly, HUVEC cells were seeded 24 h after siRNA transfection. 24 h later, the medium was replaced by basal medium in the presence or not of 20 mm E-64. After 2 h, both VEGF (20 ng/ml) and endostatin (10−14 to 10−6 m) were added. Cell proliferation was determined as described previously.

Caspase-3 Activity

HUVEC cells were seeded in a 24-well plate (100,000 cells/well) for 24 h before addition of VEGF (20 ng/ml) in basal medium together with endostatin or its hydrolysis products (0.1 mm) or endostatin-derived peptides (G10T and K15T, 10−8 to 10−6 m). After 10 h, cells were rinsed with PBS and then lysed (buffer lysis, 20 mm Tris buffer, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 2 ml of EGTA, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 100 mm PMSF, 10 mg/ml leupeptin, 10 mg/ml aprotinin, 5 mg/ml pepstatin, and 0.2% Nonidet P40). The proteolytic activity of caspase-3 was measured in the presence of 50 mm Z-DEVD-AMC (excitation wavelength = 380 nm, emission wavelength = 450 nm; Spectramax Gemini) in 0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 0.1 m NaCl, 5% sucrose, 0.1% CHAPS, 10 mm DTT. Assays were repeated in the presence of 50 mm Z-DEVD-FMK, an irreversible caspase-3 inhibitor.

Migration Assays

Fibronectin-coated (50 ng/ml, 1 h, 37 °C) filter inserts (pores, 8-mm diameter) were positioned on 24-well plates (Becton Dickinson) in the presence of VEGF (20 ng/ml) as chemoattractant. Control was performed in the absence of VEGF. Trypsinized HUVEC cells (250,000 cells/ml) were treated for 15 min at 37 °C with endostatin (0.1 mm) or its hydrolysis fragments (0.1 mm) and then placed in inserts (50,000 cells/insert) for 5 h. After fixation for 10 min in methanol and staining with hematoxylin for 2 min, cells present in the lower section were counted (median of three fields/insert) using an inverted microscope (magnification ×200). Experiments were repeated with both G10T and K15T (10−8 to 10−6 m). Alternatively, siRNA-transfected cells were seeded 24 h after transfection in 24-well plates (250,000 cells per well). After 24 h, complete medium was replaced with basal medium in the presence or absence of E-64 (20 mm) and recombinant endostatin was added (10−9 to 10−7 m). After 12 h, cells were taken off and placed on inserts, and migration assays were carried out as described previously.

Aminopeptidase N Assay

Assays were carried out by preincubating APN (20 ng) for 15 min at 37 °C in 50 mm Tris buffer, pH 7.0, prior adding H-Ala-AMC (100 mm) as recommended by the supplier (excitation wavelength, 380 nm; emission wavelength, 460 nm; Spectramax Gemini). Inhibitory assays were performed in the presence of bestatin, G10T, and Sc-G10T (0–200 mm), and results were reported as means ± S.D. (triplicate experiments).

Endothelial Tube Formation Assay

Two hundred microliters of Matrigel (10 mg/ml, BD Biosciences) was applied to pre-cooled 48-well plates, incubated for 10 min at 4 °C, and then allowed to polymerize for 1 h at 37 °C. HUVECs (1 × 105 cells per well, TCS Cellworks, Buckingham, England) were incubated with a range of predetermined concentrations of bestatin, G10T, Sc-G10T, or vehicle-only controls. After incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 16 h, cells were viewed using a Nikon Eclipse TE300 microscope and images taken using a Nikon DXM1200 digital camera (×20 magnification). Total tubule branching was counted, and results were expressed as the total length of tubule formation per field of view. All variables were performed in duplicate, and seven images were taken from each replicate before analysis (17).

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of cell proliferation, migration, apoptosis, and tube formation assays were performed by using a non-parametric multiple comparison test (Kruskal and Wallis test). Data were presented as median ± lower and upper quartile (*, p < 0.1; **, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001).

RESULTS

In Vitro Release of Human Endostatin by Cysteine Cathepsins

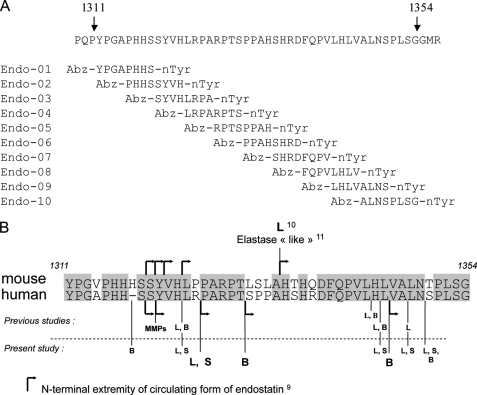

Although the proteases responsible for the liberation of endostatin in mice have been partially characterized, the processing mechanisms for human endostatin remain unresolved (10). One of the likely reasons for the differences observed between human and mouse endostatin may depend on key amino acid substitutions (e.g. substitution of non-polar Leu-1323 by Pro, a constrained residue), hence influencing cathepsin specificity especially at the S2 subsite, its major specificity determinant (18). Given the lack of a commercial source of purified or recombinant collagen XVIII, 10 overlapping FRET peptides (Endo-01 to Endo-10) corresponding to the hinge region of the NC-1 domain were synthesized (Fig. 1A). Although peptides Endo-01, Endo-02, Endo-06, and Endo-07 were resistant or weakly susceptible to hydrolysis by cysteine cathepsins, two regions were particularly sensitive to proteolysis, albeit with different specificity constants (kcat/Km) (Table 2). The first region corresponded to peptides Endo-03 to Endo-05, and the second region corresponded to peptides Endo-08 to Endo-10, with higher specificity constants for the latter. Cathepsins L and S cleaved Endo-08 and Endo-09 between residues His-1344 and Leu-1345, and Endo-10 between Ala-1347 and Leu-1348 (human collagen XVIII numbering). These findings are in agreement with the previously proposed cleavage sites of the NC-1 domain, but they do not match any of N-terminal forms of circulating endostatin that have been characterized (9, 19, 20). However, cathepsin B cleaved Endo-09 between Leu-1345 and Val-1346, which does correspond to the N terminus of the shorter molecular variety of endostatin (∼20 kDa) found in human plasma for which no other candidate protease has been identified to date (9). Furthermore, cathepsin B cleaved peptides Endo-04 and Endo-05 between Thr-1329 and Ser-1330, which also corresponds to a physiological form of endostatin in circulation. In addition to the effects of cathepsin B, our data also highlighted that the Endo-03 peptide was susceptible to both cathepsins L and S at the same cleavage site (His-1322–Leu-1323) as observed for murine endostatin. A secondary cleavage site (Arg-1324–Pro-1325) in Endo-03 was identified for cathepsins L and S, which was of particular interest because it corresponds to the N terminus of the circulating ∼22-kDa form of human endostatin (Fig. 1B). Likewise, cathepsin V that is highly expressed in corneal epithelium and participates in the generation of endostatin in human limbocorneal epithelial cells (21) displayed peptidase properties similar to the closely related cathepsins L and S (44). Cathepsin H did not hydrolyze peptides Endo-01 to Endo-10.

FIGURE 1.

Sequences of overlapping FRET peptides and proteolysis-sensitive hinge region of the NC-1 domain of human and mouse collagen XVIII. A, design of FRET-peptides. Ten overlapping 10-mer peptides (Endo-01 to Endo-10), with a four-residue stagger and spanning the proteolysis-sensitive hinge region of the NC-1 domain of collagen XVIII, were synthesized as FRET peptides and are flanked by an N-terminal fluorescence donor (Abz), and a C-terminal quenching acceptor (3-Tyr-NO2). B, hinge region of both murine and human NC-1 domains. Positions of cleavage sites identified by in vitro assays are compared with in vivo circulating endostatin (identified by N-terminal sequencing) found in human plasma (residues 1311–1354: human collagen XVIII numbering: Swissprot access no. 39060). Upper characters for cathepsins L, S, and B relate to cleavage sites matching with previously described circulating forms of human endostatin (9); their corresponding N-terminal residues are Pro-1325, Ser-1330, and Val-1346.

TABLE 2.

Specificity constants for the hydrolysis of FRET peptides (Endo-01 to Endo-10) corresponding to the hinge region of the C-terminal domain of collagen XVIII

Second-order rate constants (kcat/Km) were measured under pseudo-first order conditions (see “Experimental Procedures” for details) and were reported as means ± S.D. (experiments done in triplicate). Hydrolysis products were separated by reverse-phase HPLC, and cleavage sites were identified by mass spectrometry. N.H., no hydrolysis; Cat, cathepsin. Cleavage of Endo-03 by cathepsin B had no relevance (between Ala-1326 at the C terminus and 3-nitro-tyrosine, the extra fluorescence quencher group).

| Peptides |

kcat/Km |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cat L | Cat S | Cat B | |

| mm−1·s−1 | |||

| 01 | N.H. | N.H. | 17 ± 1 |

| 02 | <10 | N.H. | N.H. |

| 03 | 730 ± 60 | 154 ± 10 | 121 ± 22 |

| 04 | N.H. | N.H. | 399 ± 25 |

| 05 | <10 | <10 | 132 ± 18 |

| 06 | N.H. | N.H. | N.H. |

| 07 | N.H. | N.H. | N.H. |

| 08 | 266 ± 23 | 2049 ± 16 | N.H. |

| 09 | 3490 ± 355 | 2659 ± 362 | 170 ± 21 |

| 10 | 713 ± 87 | 276 ± 24 | 260 ± 36 |

Gene Silencing by Specific siRNAs of Cathepsins L and S Impairs Release of 22-kDa Endostatin in HUVECs

HUVECs were chosen as a model to examine the functional significance of endostatin hydrolysis by the cysteine cathepsins. Endothelial cells expressed active cathepsins B and L and to a lesser amount, cathepsin S, although we did not detect cathepsin K, which is in agreement with previous studies (22). Compared with the proteolytic activity determined in the presence of the broad spectrum inhibitor, E-64, titration by CA-074 showed that the predominant cysteine protease was cathepsin B (∼100 nm). Transient knockdown of cathepsins B, L, and S was achieved by transfection of HUVECs by specific small interfering RNAs. Inhibition of transcription was determined to be optimal at 24 h for cathepsin B and at 24–48 h for both cathepsins L and S as determined by quantitative real-time PCR (supplemental Fig. 1A). This message knockdown was further validated by reduced protein levels of mature cathepsins (supplemental Fig. 1B) as well as proteolytic activities (data not shown). No immunoreactive endostatin was found in the cell-free supernatants, whereas several species were detected in cell lysates, in agreement with previous reports showing that endostatin remains associated with the endothelial membrane surface after its release from collagen XVIII (23), most probably via tight interactions with membrane molecular partners (e.g. integrins, transglutaminase-2, or VEGF-receptor) (8). Depletion of cathepsins B, L, and S by siRNA did not impair the presence of the high molecular mass (∼37–38 kDa) endostatin form (Fig. 2A), in agreement with an earlier observation that MMPs, but not cathepsins, predominantly hydrolyze the hinge region of the NC-1 domain for the generation of >30-kDa endostatin species (19). Conversely, the major band corresponding to the ∼22-kDa endostatin species (Fig. 2A, siCTL) was diminished noticeably in cells depleted of cathepsins L or S but remained unaffected by the knockdown of cathepsin B. Whereas cathepsin L was described to directly release ∼20-kDa endostatin in mice (10), these results support that both cathepsins S and L play a key role in mediating the production of the ∼22-kDa human endostatin species, in agreement with the in vitro FRET peptides assays.

FIGURE 2.

Consequences of gene silencing of cathepsins L and S. A, consequences of transient inhibition of cathepsins L, S, and B on level of endogenous 22-kDa endostatin. At 48 h post-transfection, HUVECs were lysed, and the protein level of endogenous endostatin was analyzed by Western blot in the presence of siRNAs. siCTL, control siRNA; siCatB, siRNA directed against cathepsin B; siCatL, siRNA directed against cathepsin L; siCatS, siRNA directed against cathepsin S. B, proliferation assays: At 48 h post-transfection, proliferative properties of HUVECs were analyzed in the presence of VEGF (20 ng/ml). Assays were conducted in the presence of exogenous human endostatin as described under “Experimental Procedures.” E-64 (20 μm) was added in the medium for a control (CTL) experiment (n = 6, results are expressed as median). C, migration assays. At 48-h post-transfection with siRNAs directed against cathepsins, anti-migrative properties of exogenous endostatin were analyzed in a Boyden chamber. VEGF (20 ng/ml) was used as chemoattractant. A control experiment was made in the presence of E-64 (20 μm) (n = 6, results are expressed as median).

We next considered the phenotypic alterations on endothelial cells as a result of the cathepsin species depletion by siRNA. Gene silencing of cathepsin S but neither cathepsins B nor L resulted in a decrease of proliferation of HUVECs (supplemental Fig. 2A), whereas knockdown of either cathepsins L or S, but not cathepsin B, abrogated their ability to migrate on fibronectin-coated surfaces (supplemental Fig. 2B). These results are in agreement with previous reports supporting that cathepsins may have partially overlapping but also distinctive roles in invasion and proliferation (see Refs. 17 and 24–26 for examples).

On the basis of these findings, we next examined the effect of cathepsin knockdown on the anti-angiogenic potency of endostatin. Recombinant endostatin (10−14 to 10−6 m) was added to the cell medium in cells depleted of each cathepsin species (Fig. 2, B and C). The anti-proliferative properties of exogenous endostatin (EC50 = 170 pm) were not significantly affected by the silencing of cathepsin B (EC50 = 80 pm) but were markedly reduced by the down-regulation of both cathepsins L and S (EC50 = 9.3 and 40 nm, respectively). This decrease in the anti-angiogenic activity of endostatin compared with control in the presence of E-64, which is a poor cell-permeable irreversible cathepsin inhibitor (EC50 = 18 nm) (Fig. 2B). Further dose-response assays showed that the amount of endostatin necessary to achieve maximal anti-proliferative activity toward HUVECs must be significantly increased after addition of E-64 or transfection by siCatL and siCatS but not by siCatB. Conversely, silencing of cathepsins B, L, or S or treatment with E-64 did not modify dose-dependent anti-migrative properties of endostatin (Fig. 2C), indicating that endostatin is a potent anti-proliferative but a weakly anti-migrative molecule. Moreover, these results also suggest that both human cathepsin L and S may be involved in the direct release of the ∼22-kDa endostatin species, unlike that observed for the murine counterpart that only requires cathepsin L (10).

The demonstration that cathepsins L and S, at least in vitro, can further degrade endostatin, suggests that a subtle mechanistic regulation of its angiostatic properties may occur (19). In agreement with this hypothesis, synthetic endostatin-derived peptides with potent anti-angiogenic properties have been described previously (27, 28). Therefore, we postulated that the subsequent proteolysis of the ∼22-kDa endostatin by cathepsins L and S may lead to the release of endostatin fragments with more potent anti-proliferative properties than the parental molecule.

Anti-angiogenic Properties of Hydrolysis Products of Endostatin

To examine the possibility that cathepsins L and S could potentiate endostatin through further processing, recombinant endostatin was incubated in the presence of cathepsin L, S, or B and analyzed by Western blot. Conversely to cathepsin B, cathepsins L and S hydrolyzed endostatin efficiently in vitro (see supplemental Fig. 3, A and B), whereas cathepsin H did not display any discernable effects. Cleavage sites, identified by RP-HPLC and mass spectrometry analyses, correspond to the release of several ∼15-mer peptidyl fragments (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Hydrolysis of human endostatin by cathepsins L and S: location of cleavage sites. Following incubation with cathepsins L and S, hydrolysis products were separated by reverse-phase HPLC and identified by mass spectrometry, and cleavage sites were deduced from mass analysis (human collagen XVIII numbering: Swissprot access no. 39060). Positions of both 10-mer G10T (1455GSDPNGRRLT1464) and 15-mer K15T (1450KSVWHGSDPNGRRLT1464) peptides are highlighted in gray and light gray, respectively. Arrowheads correspond to identified cleavage sites.

We next examined whether any of these peptides were capable of eliciting the angiostatic properties of the parent molecule. HUVECs were first incubated with the whole endostatin hydrolysate (where the cathepsin species had been inactivated with E-64), in the culture medium. A cell proliferation assay was performed in the presence of VEGF to induce effective proliferation as 0.1 μm endostatin alone had no discernable effect (Fig. 4A). The cathepsin B-generated hydrolysate had no anti-proliferative effects on HUVECs. Conversely and compellingly, hydrolysis products generated by cathepsin L fully inhibited cell proliferation (p < 0.05), clearly demonstrating that one (or more) endostatin-derived peptide(s) displayed potent anti-proliferative effects. Under the same experimental conditions, the cathepsin S hydrolysate, which has a proteolysis pattern close to that of cathepsin L, inhibited proliferation ∼60%. The ability of hydrolysis products to modulate caspase-dependent apoptosis was then analyzed. As observed for proliferation assays, 0.1 mm endostatin did not modulate caspase-3 activity. In contrast, cathepsins L and S hydrolysates stimulated caspase-3 like activity (Fig. 4B). Finally, migration of HUVECs was restored following preincubation of endostatin with cathepsins, using VEGF as chemo-attractant, pointing out that cleavage of endostatin impaired its anti-migrative potency (Fig. 4, C and D).

FIGURE 4.

Anti-angiogenic properties of hydrolysis products of human endostatin. A, proliferation assays. Following incubation for 4 h at 37 °C in the presence of cysteine cathepsins (enzyme/substrate molar ratio, 1:5), hydrolysis products of endostatin (0.1 mm) were assayed on HUVECs in the presence of VEGF (20 ng/ml). Native recombinant endostatin (0.1 mm) was used as control. After a 2-h incubation in the presence of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium,absorbance was measured (A = 490 nm). Results are expressed as the percentage of the difference in absorbance observed in the presence or not of VEGF (n = 12, data reported as median ± quartiles). B, caspase-3 activity: Experiments were done in the presence of VEGF (20 ng/ml). Ability of native endostatin (0.1 mm) or its hydrolysis products (0.1 mm) to induce apoptosis in HUVECs was determined by measurement of the proteolytic activity of caspase toward Z-DEVD-AMC (50 mm). Results were normalized with respect to the hydrolysis of Z-DEVD-AMC in the presence of VEGF alone. The specificity of caspase-dependent AMC release was checked by addition of 50 mm Z-DEVD-FMK (not shown here) (n = 6, data expressed as median ± quartiles). C, migration assays. Briefly, HUVEC cells were treated for 15 min at 37 °C with endostatin (0.1 mm) or its hydrolysis fragments (0.1 mm) and then placed in fibronectin-coated filter inserts for 5 h (24-well plates) in the presence of VEGF (20 ng/ml). Cells that have migrated in the lower section of the Boyden chamber were counted as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Results are expressed as the ratio of cells that have migrated in the absence of chemoattractant (n = 6, data expressed as median ± quartiles). D, immunoblotting analysis. Residual uncleaved endostatin was revealed by an anti-endostatin antibody following its incubation with cathepsins. *, p < 0.1; **, p < 0.05.

The hydrolysis products were further separated by C18 RP-HPLC and the anti-proliferative potency of resulting individual peaks analyzed to identify bioactive peptides. Two peaks (eluted at 31.5 and 44% of acetonitrile, respectively, using a linear 0–60% gradient in the presence of 0.1% TFA) inhibited cell proliferation. These molecules, characterized by mass spectrometry, were, respectively, the decapeptide 1455GSDPNGRRLT1464 and the peptide 1450KSVWHGSDPNGRRLT1464 encompassing the same 10-mer sequence with a N-terminal extension (i.e. KSVWH) of five amino acids (Fig. 3C). Corresponding peptides, subsequently referred to as G10T and K15T, were synthesized, and their ability to modulate proliferation, apoptosis, and migration of endothelial cells were analyzed as done previously. Both peptides exhibited potent anti-proliferative properties on HUVECs (Fig. 5A), but the shorter G10T was significantly more effective (EC50 = 0.23 nm) than K15T (EC50 = 5.16 nm). When taken together with the fact that recombinant endostatin in the presence of E-64 had no significant effects on proliferation of HUVECs at this concentration range (10−12 to 10−7 m), suggests that the anti-proliferative activity of endostatin in fact results from endostatin-derived peptides generated by cathepsins L and S (Fig. 2D). Both peptides also exhibited significant proapoptotic properties, with G10T proving more potent (EC50 = 10−10 m; p < 0.05) than K15T (EC50 = 10−8 m; p < 0.05) on HUVECs (Fig. 5B). In contrast, and in agreement with findings presented above, both peptides displayed poor anti-migratory properties, as migration of HUVECs was not altered at 10−7 m and is reduced by ∼50% at 10−6 m (Fig. 5C). This set of experiments demonstrated that G10T and K15T, produced from proteolytic cleavage by cathepsins S and L, exhibit more potent proapoptotic and angiostatic effects than endostatin itself. However, these data also highlight that the anti-migratory effects of endostatin are impaired by the action of cathepsins L and S.

FIGURE 5.

Angiostatic activities of endostatin-derived G10T and K15T. A, proliferation assays of HUVECs. Dose-response effects of G10T and K15T peptides were determined in the presence of VEGF (20 ng/ml). EC50 were calculated by using GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA). Data are reported as median ± quartiles (n = 10). B, caspase-3 activity. Dose-response proapoptotic effects of peptides G10T and K15T were determined in the presence of VEGF (20 ng/ml) (n = 9, data expressed as median ± quartiles). C, migration assays. HUVECs were treated for 15 min at 37 °C with peptides G10T and K15T then placed in fibronectin-coated filter inserts for 5 h (24-well plates) in the presence of VEGF (20 ng/ml). Cells that have migrated in the Boyden chamber were counted, and results were reported as previously described (n = 9, data correspond to median ± quartiles). White bar, G10T; gray bar, K15T. *, p < 0.1; **, p < 0.05. Dashed lines correspond to control values (100%).

Endostatin-derived Peptide G10T Impairs Endothelial Tube Formation via Inhibition of Aminopeptidase N

Examination of their primary sequences showed that both G10T and K15T encompass an Asn-Gly-Arg motif that has been reported to home selectively to tumor vasculature in vivo (29). This sequence has been used to improve the efficacy of anti-angiogenic and anti-tumorigenic agents through targeting to tumor sites; this effect is facilitated through the ability of the NGR sequence to target and bind APN (CD13) (30, 31). APN is a zinc-binding type 2 transmembrane ectopeptidase of 150 kDa (Clan MA, family M1; Merops, the peptidase database) that is expressed selectively in vascular endothelial cells, including HUVECs and aortic endothelial cells (32). Previously, it has been shown that a synthetic NGR-containing peptide derived from endostatin (corresponding to the Ser-1451–Thr-1464 moiety and encompassing the sequence of presently identified peptides) binds to and inhibits APN more strongly than bestatin, which is its pharmacological inhibitor isolated from Streptomyces olivoreticuli and currently used as an anticancer drug (33, 34). Of major interest, endostatin itself was unable to bind to APN and induce these effects; moreover, APN inhibition is dependent on the correct presentation and/or accessibility of the NGR motif (34). We therefore hypothesized that the G10T and K15T peptides were eliciting their biological effect through binding to APN on the surface of the HUVECs and that the smaller peptide was more potent on the basis of weaker steric hindrance and therefore easier access of binding to APN.

Consequently, inhibition assays were performed in the presence of G10T (GSDPNGRRLT) and its scrambled control Sc-G10T (GNPTDLRSRG). G10T inhibited APN within a concentration range comparable with bestatin, whereas scrambled G10T did not (Fig. 6A), confirming that G10T has the ability to bind to and inhibit APN. We next examined whether G10T had a similar effect to bestatin, a known inhibitor of APN, using a tube formation model. HUVECs were treated with bestatin, G10T, Sc-G10T, or vehicle-only controls before counting total tubule branching. G10T specifically impaired tubule formation, whereas Sc-G10T exerted no anti-angiogenic effect (Fig. 6B). Total endothelial tube length was decreased by ∼25% in the presence of bestatin and G10T, respectively; conversely, no additional decrease of tube formation was observed in the presence of both bestatin and G10T (Fig. 6C). Given that bestatin and G10T inhibited tube formation to similar levels, and in the absence of any cumulative or synergistic effects, data support the hypothesis that NGR-containing G10T can bind to APN. In addition, these results are consistent with functional analysis showing that knockdown of APN resulted in a similar inhibition of capillary tube formation using HUVECs (32). Also, present data somewhat shed new light on apparently perplexing results regarding anti-proliferative versus anti-migratory effects of endostatin and/or its hydrolysis products, given that APN participates in cell motility and invasion processes (35). Conversely, its role in migration is still subject to discussion, as bestatin effectively induces caspase-dependent apoptosis and inhibits the invasion process of endothelial cells through Matrigel but not migration (36).

FIGURE 6.

Inhibition of APN/CD13 and impairment of tube formation by the G10T peptide. A, recombinant human APN (20 ng/assay) was incubated for 15 min at 37 °C in the presence of bestatin, G10T, and Sc-G10T (final concentration, 0–200 mm) before adding H-Ala-AMC (100 mm). Residual enzymatic activity of APN was deduced from the release of AMC (excitation wavelength, 380 nm; emission wavelength, 460 nm) (experiments done in triplicate; n = 3). Results were reported as means ± S.D. B, endothelial tube formation assay. 1 × 105 endothelial cells per well were applied to Matrigel-coated 48-well plates. Cells were further incubated with G10T peptide, its scrambled form (Sc-G10T), or a vehicle-only control. Total tubule branching was counted as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and results were expressed as the average tube length per field of view (×20 magnification) (16). **, p < 0.05. C, inhibition of tube formation by G10T and bestatin. The G10T peptide and bestatin were applied alone or in combination to evaluate additive effects of the two inhibitors. Results were normalized using as reference vehicle-only control. White bar, 100 nm; gray bar, 500 nm. **, p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Proteases are key players in angiogenesis due to their ability to activate and release cytokines and angiogenic factors (matrikines) from constituents of the basement membrane and extracellular matrix. As such, they are potential therapeutic targets in the regulation of neovascularization, particularly during neoplastic processes. However, the failure of early clinical trials using MMP inhibitors clearly indicates that the sustainable molecular mechanisms remain poorly understood. Since the late 1990s, an increasing number of anti-angiogenic factors released by proteases were identified, and most studies have focused on their therapeutic impact in high pharmaceutical doses, particularly in controlling tumor progression (37). In contrast, few studies have investigated their physiological and pathophysiological roles. These latter observations demonstrate the importance of studying the regulation of these anti-angiogenic factors and raise the question of the ambivalent role of proteases involved in their homeostasis. Cysteine cathepsins are commonly reported to participate to and enhance cell growth, migration, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis, and comprehensible relationships have been established between their deregulation and cancer progression (25, 26, 38). For instance, cathepsin S, which can degrade anti-angiogenic collagen IV-derived peptides and release proangiogenic fragments from laminin, has been described to favor angiogenesis and microvessel formation in physiological neovascularization (39). Nevertheless, our current perception of the role of cathepsins is evolving. In addition to digestive and executioner enzymes, cathepsins that are subject to complex and contrasting controls and checkpoints (transcription, translation, trafficking, and microenvironment) may also act as signaling and regulatory molecules (40). More than 30 proteases, including cysteine cathepsins, have been catalogued with beneficial tumor-suppressive roles in opposition to the currently established rule that their up-regulation is synonymous with tumor progression and poor clinical prognosis (41). Contrary to other previous studies, cathepsin L KO mice displayed early onset aggressive tumors and an hyperproliferation of keratinocytes in a skin carcinogenesis model, proving that cathepsin L may have a protective role in cancer in association with its critical role for the termination of growth factor signaling (42, 43). These statements emphasize that proteases may have dual roles and exert for instance opposing proangiogenic and angiostatic effects. Such proteases do not represent rare exceptions and, most probably, in a defined biological context, their number will grow depending on tissue type, cellular microenvironment, and surrounding signaling events (13, 41). As a consequence this also means a supplementary level of difficulty to delineate proangiogenic and anti-angiogenic properties of proteases with challenging activities and to assign a specific role to them. Our current findings support that cathepsins L and S release endostatin fragments with superior proapoptotic and angiostatic properties than its precursor, although they are both better known for their opposite action. Also our results suggest that, besides recycling properties with respect to the release and hydrolysis of the NC1 domain of collagen XVIII, cysteine cathepsins could have a likely regulatory function of angiogenesis via the generation of angiostatic peptides K15T and G10T. In conclusion, earlier reports have proposed that endostatin may be released proteolytically from collagen XVIII by various potential proteases including cathepsins, elastase, and MMPs. Furthermore, some cysteine cathepsins and acid cathepsin D, in contrast to MMPs, were also candidates to degrade endostatin, suggesting a complex role for cathepsins in the regulation of its anti-angiogenic potential (19). Here, we showed that cathepsins S and L liberate human endostatin by cleavage in the C-terminal sensitive hinge region of collagen XVIII (Fig. 7). Cathepsins L and S may then further cleave human endostatin and generate peptides (i.e. G10T and K15T), which display significantly increased angiostatic properties. Specifically, we have demonstrated that the endostatin-derived G10T peptide potently inhibits proliferation of HUVECs, is an effective proapoptotic molecule, and significantly impairs tube formation, suggesting that it could participate in the homeostasis of vascularization. In addition, we hypothesized that the bioactive NGR-containing G10T peptide act, at least in part, through targeting of aminopeptidase N.

FIGURE 7.

Release of angiostatic peptides by cysteine cathepsins S and L. Both G10T (1455GSDPNGRRLT1464) and K15T (1450KSVWHGSDPNGRRLT1464) peptides enclose an NGR tumor-homing motif (highlighted in light gray) with enhanced anti-proliferative and proapoptotic potencies compared with the parent endostatin toward endothelial cells (human collagen XVIII numbering). Experimental data also support that biological effects of G10T could be mediated by molecular interactions with APN/CD13, which is already known to be the pharmacological target of bestatin.

Given the superior anti-angiogenic efficacy of such peptides, they could be of enhanced therapeutic value compared with commercial full-size endostatin (also known as Endostar). Furthermore, due to the presence of the NGR neovasculature homing motif that targets and binds to APN as does bestatin, endostatin-derived peptides could also represent attractive cargos by conjugation to additional anticancer drugs to improve anti-angiogenic efficiency and bioavailability.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Valérie Labas (Laboratoire de Spectrométrie de Masse, Plateau d'analyze Intégrative des Biomarqueurs Cellulaires et Moléculaires, Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Tours-Nouzilly, France) for mass spectrometry analysis.

This work was supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM) and a grant from l'Institut Fédératif de Recherche “Imagerie Fonctionnelle” (IFR 135, Tours, France).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–3.

- HUVEC

- human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- AMC

- 7-amino-4-methyl coumarin

- APN/CD13

- aminopeptidase N

- CA-074

- N-(l-3-trans-propylcarbomoyl-oxirane-2-carbonyl)-l-isoleucyl-l-proline

- E-64

- L-trans-epoxysuccinyl-leucylamido-(4-guanidio)butane

- FMK

- fluoromethyl ketone

- MMP

- matrix metalloproteinase

- RP

- reverse phase

- Z

- benzyloxycarbonyl.

REFERENCES

- 1. O'Reilly M. S., Boehm T., Shing Y., Fukai N., Vasios G., Lane W. S., Flynn E., Birkhead J. R., Olsen B. R., Folkman J. (1997) Cell 88, 277–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marneros A. G., Olsen B. R. (2001) Matrix Biol. 20, 337–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ling Y., Yang Y., Lu N., You Q. D., Wang S., Gao Y., Chen Y., Guo Q. L. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 361, 79–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dhanabal M., Volk R., Ramchandran R., Simons M., Sukhatme V. P. (1999) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 258, 345–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dixelius J., Cross M., Matsumoto T., Sasaki T., Timpl R., Claesson-Welsh L. (2002) Cancer Res. 62, 1944–1947 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Folkman J. (2006) Exp. Cell Res. 312, 594–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yamaguchi N., Anand-Apte B., Lee M., Sasaki T., Fukai N., Shapiro R., Que I., Lowik C., Timpl R., Olsen B. R. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 4414–4423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Faye C., Inforzato A., Bignon M., Hartmann D. J., Muller L., Ballut L., Olsen B. R., Day A. J., Ricard-Blum S. (2010) Biochem. J. 427, 467–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. John H., Preissner K. T., Forssmann W. G., Ständker L. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 10217–10224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Felbor U., Dreier L., Bryant R. A., Ploegh H. L., Olsen B. R., Mothes W. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 1187–1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wen W., Moses M. A., Wiederschain D., Arbiser J. L., Folkman J. (1999) Cancer Res. 59, 6052–6056 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ständker L., Schrader M., Kanse S. M., Jürgens M., Forssmann W. G., Preissner K. T. (1997) FEBS Lett. 420, 129–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mason S. D., Joyce J. A. (2011) Trends Cell Biol. 21, 228–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Godat E., Lecaille F., Desmazes C., Duchêne S., Weidauer E., Saftig P., Brömme D., Vandier C., Lalmanach G. (2004) Biochem. J. 383, 501–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Serveau C., Lalmanach G., Juliano M. A., Scharfstein J., Juliano L., Gauthier F. (1996) Biochem. J. 313, 951–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Serveau-Avesque C., Martino M. F., Hervé-Grépinet V., Hazouard E., Gauthier F., Diot E., Lalmanach G. (2006) Biol. Cell 98, 15–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Burden R. E., Gormley J. A., Jaquin T. J., Small D. M., Quinn D. J., Hegarty S. M., Ward C., Walker B., Johnston J. A., Olwill S. A., Scott C. J. (2009) Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 6042–6051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lecaille F., Kaleta J., Brömme D. (2002) Chem. Rev. 102, 4459–4488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferreras M., Felbor U., Lenhard T., Olsen B. R., Delaissé J. (2000) FEBS Lett. 486, 247–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Farias S. L., Sabatini R. A., Sampaio T. C., Hirata I. Y., Cezari M. H., Juliano M. A., Sturrock E. D., Carmona A. K., Juliano L. (2006) Biol. Chem. 387, 611–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ma D. H., Yao J. Y., Kuo M. T., See L. C., Lin K. Y., Chen S. C., Chen J. K., Chao A. S., Wang S. F., Lin K. K. (2007) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48, 644–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chang S. H., Kanasaki K., Gocheva V., Blum G., Harper J., Moses M. A., Shih S. C., Nagy J. A., Joyce J., Bogyo M., Kalluri R., Dvorak H. F. (2009) Cancer Res. 69, 4537–4544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Suhr F., Brixius K., Bloch W. (2009) Curr. Pharm. Des. 15, 389–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gocheva V., Zeng W., Ke D., Klimstra D., Reinheckel T., Peters C., Hanahan D., Joyce J. A. (2006) Genes Dev. 20, 543–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mohamed M. M., Sloane B. F. (2006) Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 764–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vasiljeva O., Reinheckel T., Peters C., Turk D., Turk V., Turk B. (2007) Curr. Pharm. Des. 13, 387–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iozzo R. V. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 646–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xu H. L., Tan H. N., Wang F. S., Tang W. (2008) Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 9, 275–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arap W., Pasqualini R., Ruoslahti E. (1998) Curr. Opin. Oncol. 10, 560–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pasqualini R., Koivunen E., Kain R., Lahdenranta J., Sakamoto M., Stryhn A., Ashmun R. A., Shapiro L. H., Arap W., Ruoslahti E. (2000) Cancer Res. 60, 722–727 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Corti A., Curnis F., Arap W., Pasqualini R. (2008) Blood 112, 2628–2635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fukasawa K., Fujii H., Saitoh Y., Koizumi K., Aozuka Y., Sekine K., Yamada M., Saiki I., Nishikawa K. (2006) Cancer Lett. 243, 135–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mucha A., Drag M., Dalton J. P., Kafarski P. (2010) Biochimie 92, 1509–1529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yokoyama Y., Ramakrishnan S. (2004) Br. J. Cancer 90, 1627–1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yoneda J., Saiki I., Fujii H., Abe F., Kojima Y., Azuma I. (1992) Clin. Exp. Metastasis 10, 49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bauvois B., Dauzonne D. (2006) Med. Res. Rev. 26, 88–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nyberg P., Xie L., Kalluri R. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 3967–3979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Turk B. (2006) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5, 785–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang B., Sun J., Kitamoto S., Yang M., Grubb A., Chapman H. A., Kalluri R., Shi G. P. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 6020–6029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Reiser J., Adair B., Reinheckel T. (2010) J. Clin. Invest. 120, 3421–3431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. López-Otín C., Matrisian L. M. (2007) Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 800–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Reinheckel T., Hagemann S., Dollwet-Mack S., Martinez E., Lohmüller T., Zlatkovic G., Tobin D. J., Maas-Szabowski N., Peters C. (2005) J. Cell Sci. 118, 3387–3395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dennemärker J., Lohmüller T., Mayerle J., Tacke M., Lerch M. M., Coussens L. M., Peters C., Reinheckel T. (2010) Oncogene 29, 1611–1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Veillard F. (2009) Inflammations pulmonaires et protéases à cystéine: Résistance des cathepsines au stress oxydatif et implication dans la régulation de l'angiogenèse. Ph.D. thesis, University François Rabelais, Tours, France [Google Scholar]