Abstract

Low-income children perform better in school when school-focused future identities are a salient aspect of their possible self for the coming year and these school-focused future identities are linked to behavioral strategies (Oyserman et al., 2006). Hierarchical linear modeling of data from a four-state low-income neighborhood sample of eighth-graders suggests two central consequences of family and neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation on children’s school-focused possible identities and strategies. First, higher neighborhood disadvantage is associated with greater salience of school in children’s possible self for the coming year. Second, disadvantage clouds the path to school-success; controlling for salience of school-focused possible identities, children living in lower socioeconomic status families and boys living in more economically disadvantaged neighborhoods were less likely to have strategies to attain their school-focused possible identities. The influence of family socioeconomic status was seen particularly with regard to strategies to attain academic success and teacher engagement aspects of school-focused identities.

In the United States there is a clear disjuncture between the expectations and outcomes of low-income and minority children. Almost half of low-income and minority students do not graduate from high school (Orfield, 2004, 2006). Risk of school failure is higher in neighborhoods (Aronson, 1997; Brooks-Gunn et al., 1993; Corcoran, Gordon, Laren, & Solon, 1992; Dornbusch, Ritter, Steinberg, 1991; Duncan, 1994; Entwisle et al., 1994; Halpern-Felsher et al., 1997) and families (DeGarmo et al., 1999; Mercy & Steelman, 1982; Scarr & Weinberg, 1978) with fewer socioeconomic resources. Yet, when asked, low-income children expect to do well in school. Most low-income and minority eighth graders in nationally representative U.S. samples report that they expect to attend college (Mello, 2009), whether or not they are currently at grade-level in their schoolwork or planning to take a college preparation track in high school (Mello, 2009; Trusty, 2000).

We interpret this contrast between children’s outcomes and aspirations as meaning that low income and minority children do see school success as an important destination, but that for these children, the path to school success may not be clear. That is, children from socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts may be less aware that attaining the college-bound aspect of their distal (but possible) self requires sustained current school-focused effort, and because the path is not clear, they may fail to devote sufficient school-focused effort toward achieving academic success (for related conceptualizations, see Cook et al., 1996; Mickelson, 1990). If so, children from socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts may be less in need of intervention to raise their long-term expectations for school-success than in need of intervention to link these expectations to more proximal goals (e.g., doing well in school this year) and current behavioral strategies (e.g., studying every night). To better understand how children from socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts articulate school-focused possible identities and strategies to attain them within their proximal possible self, research is needed that focuses explicitly on these children and the factors associated with their school-focused possible identities and strategies. Therefore, in the current study, we focus on the expected possible self of children from socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts and examine an aspect of this possible self – children’s school-focused possible identities and strategies.

An expected possible self is the generally positive image children have of who they would like to be in the future (Oyserman & Markus, 1990a, 1990b). Possible selves differ from general expectations or aspirations in that they are vivid images of the self attaining a future state, rather than simply thoughts, wishes, or desires about the future (Markus & Nurius, 1986; Seignor, 2009). Possible selves are composed of various specific possible identities (e.g. “good student”) which can be linked to behavioral strategies or steps one is currently taking to make progress toward a particular possible identity (Oyserman & James, in press). Strategies are assessed by simply asking children if they are doing anything to work toward a particular possible identity (Oyserman & Saltz, 1993). Prior research demonstrates that the identities that make up children’s expected possible selves focus on their everyday contexts, including school, and that expected possible selves can focus on the near or far future (Oyserman & Fryberg, 2006). Like other expectations and aspirations, a possible self does not always affect behavior. Evidence that school-focused possible identities positively influence current behavior -- doing homework and paying attention in class, comes specifically from research on possible selves that are about the near future (e.g., next year) and contain school-focused possible identities linked to behavioral strategies (Oyserman et al., 2004; Oyserman, Bybee, Terry, 2006).

Indeed, an intervention focused on triggering school-focused possible identities and linking these possible identities to behavioral strategies has proven effective (Oyserman, et al., 2006; Oyserman, Terry, Bybee, 2002). Specifically, African American, Latino and White children from socioeconomically deprived contexts were randomly assigned either to an intervention or school-as-usual control. Those in the intervention group attended a brief class in which they participated in activities designed to make school-focused possible identities and strategies to attain them feel more salient. Indeed, children randomly assigned to the intervention group later reported more school-focused identities and strategies to attain them and this mediated the influence of the intervention on school performance outcomes including grades and attendance over a two-year follow-up (Oyserman, et al., 2006).

These results underscore the importance of having school-focused possible identities linked with behavioral strategies for the academic outcomes of children from socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts. However, they do not address the question of context effects. 1 One possibility is that relative socioeconomic deprivation (operationalized at either the neighborhood or family level) influences both how salient school-success identities are within a possible self and whether these school-focused future identities are linked to behavioral strategies (for theoretical arguments see Oyserman, Gant, & Ager, 1995; Oyserman & Saltz, 1993). Unfortunately, prior research on aspirations and expectations often merge goal and strategy questions by asking about educational or occupational expectations or aspirations (Massey et al., 2008). In these studies, participants are asked closed- or open-ended questions about how far they expect to go in school or the occupation they aspire to (e.g. Cook et al., 1996).

A strength of these studies is that they demonstrate an association between socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts and lower youth aspirations and expectations (e.g. for a review, Massey, Gebhardt & Garnefski, 2008; see also, Mello, 2009; Mello & Swanson, 2007; Sampson, 1997; Wilson, 1987). However, these studies also have a number of limitations. First, they do not distinguish between future expected outcomes (what we term the “destination”) and behavioral strategies (what we term the “path”), even though this distinction is clearly relevant given the gap between expectations and outcomes. Second, by focusing explicitly on adult education and occupation, these studies do not provide insight into the centrality of school-focused possible identities and the availability of strategies for attaining success in school in children’s proximal possible selves. Moreover, although family and neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation are likely to have differing effects on aspirations, expectations, and behavioral strategies, studies often confound neighborhood-level and family-level factors and race-ethnicity (e.g. Brooks-Gunn et al., 1993).

For example, in one of the few studies distinguishing between youth aspirations and expectations, Cook and colleagues (Cook et al., 1996) ask open- and close-ended questions about occupational aspirations and expectations but do not ask boys if they are doing anything to attain these expectations or aspirations. They contrast African American boys attending school in a low-income Census tract with White boys attending school in a higher income Census tract, finding both a larger gap between aspirations and expectations among boys from the low- than from the higher-income Census tract school and a greater between-group difference for expectations than for aspirations. Perhaps the high aspirations of boys from the low income Census tract were not as easily translated into high expectations because their neighborhood or family contexts do not foster knowledge of strategies and consequently, their desires were not translated into expectations. 2 However, because only boys were assessed and only two tracts compared, it is possible that between-group effects are due to neighborhood factors or to other factors – such as parental socioeconomic differences attributed to neighborhood economic factors or gender by neighborhood interaction effects.

In the current study, we aim to pinpoint these effects by examining the next year possible selves of middle school boys and girls living in relatively low-income neighborhoods and differing in family socioeconomic status. Specifically, we will examine the salience of school-focused possible identities and the extent that these identities are linked to behavioral strategies. For the reasons outlined below, we expect that family and neighborhood relative socioeconomic deprivation will be more strongly associated with strategies than school-focused possible identities per se. First, school may be central to all youth, in developed societies, school attendance is mandatory through middle school, making graduating middle school a universal expectation. Second, school-success is a nearly universal aspiration of American children across background variables (Mello, 2009). Thus school-focused possible identities are likely to be part of most youth’s next year possible self whether or not the youth has a real-life role model of how to attain academic success. However, desiring school-success as a possible identity (destination) does not clarify how to do well in school (the path). We hypothesize that youth in more disadvantaged contexts will be less likely to have strategies to attain their school-focused possible identities.

The Current Study

We examine the association between relative economic disadvantage and the nature of children’s school-focused possible selves and linked behavioral strategies, assessing relative economic deprivation at both the neighborhood-level (poverty, unemployment) and the family-level (parental education, occupational prestige) so that unique effects at each level can be described, partialing out effects of the other level (e.g. Brooks-Gunn et al., 1993). We expect effects at both family and neighborhood levels. At the parent-level, higher socioeconomic status parents may be able to suggest or model strategies to attain school-focused possible identities even if the family resides in a high-poverty neighborhood. At the neighborhood-level, lower poverty and higher employment neighborhoods may expose youth to more successful strategies to attain school-focused possible identities or highlight the need to have school-focused possible identities, even if parents do not. We included prior grade point average (GPA) in all analyses as a control variable as prior research points to an association between educational expectations and prior academic achievement (e.g., Eccles & Wigfield, 2002). Controlling for prior GPA enabled us to compare expectations among children with similar prior academic achievement.

We hypothesize that children living in more socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts will have fewer behavioral strategies to attain their school-focused possible identities. Given prior evidence of high expectations (Mello, 2009; Trusty, 2000), we expect stronger context effects on behavioral strategies than on school-focused possible identities. While no gender difference in aspiration is reported (Trusty, 200), boys are more at risk of school failure than girls (Orfield, 2006) and may be more sensitive to neighborhood conditions than girls (Crowder & South, 2003; Entwisle et al, 1994; Halpern-Felsher et al, 1997; Mello & Swanson, 2007), resulting in two gender-based hypotheses: first that gender will be negatively associated with strategies to attain school-focused possible identities, and second that gender will moderate the effect of context. Specifically, we predict stronger neighborhood effects for boys. Prior research has not argued for a stronger effect of family socioeconomic status on boys, so none was hypothesized, though this possibility was explored. Because our sample is drawn from lower income neighborhoods, we will be able to examine whether effects can be found in relatively small gradations at the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum.

We operationalized our hypotheses about the effect of gender and socioeconomic context on strategies in two ways. First, we examined effects of gender and socioeconomic context controlling for the salience of school-focused possible identities. Second, we asked if socioeconomic context moderates the relationship between salience of school-focused possible identities and number of behavioral strategies, such that children in more disadvantaged contexts are less likely to generate strategies even when they have school-focused possible identities. As detailed below, we not only counted the number of strategies to attain school-focused possible identities overall but also by specific content domain (academic performance, school sports and activities, engagement with teachers and other school staff).

Method

Sample and Procedure

We used the normative control group data collected by the Fast Track program (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1992). The sample was drawn in four states during children’s kindergarten year using a multi-stage sampling procedure whereby communities were selected first, followed by schools, and finally, children within schools. Primarily low-income communities were sampled and children were selected to be representative of the full range of kindergarten behavior from non-problematic to problematic. When children were in the eighth grade, the open-ended possible self and behavioral strategy measure (Oyserman et al., 1995; Oyserman, et al., 2002) was administered in participants’ homes by the Fast Track Project staff (Durham, North Carolina n = 75, Nashville, Tennessee n = 69, Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, n = 83, Seattle, Washington n = 57; African American n = 117, European American n = 161, Hispanic or Asian American n = 6; n = 138 male, n = 146 female) as part of a larger tracking interview.3 Parental socioeconomic status, neighborhood Census tract, and school record of grade point average were collected the previous year.

Measures

Possible self and strategies

The open-ended format of the possible self and strategy measure is user-friendly (“In the lines below, write what you expect you will be like and what you expect to be doing next year.”). The stem allowed youth to include action-focused, state-focused, or trait-focused content of their expected possible self. Youth were asked to describe up to six possible self goals and then indicate whether or not (Yes/No) they were currently working on each and, if so, to articulate what they were doing (“For each expected goal that you marked ‘Yes’, use the space to the right to write what you are doing this year to attain that goal. Use the first space for the first expected goal, the second space for the second expected goal and so on.”). There was sufficient space for students to write as many strategies as they wanted for each possible self goal. Raw possible self and strategy data were provided by the Fast Track project and content coded by University of Michigan research assistants blind to sample source and study aims. The possible self and strategy questionnaire is available at http://www.sitemaker.umich.edu/culture.self/files/possible_selves_measure.doc. Responses to the possible self stem were coded as possible identities following Oyserman and Markus’s (1990a) content coding scheme (school-achievement, interpersonal, intrapsychic traits, physical health, and material-lifestyle). Responses to the strategy stem for each possible identity were counted following Oyserman, Gant, and Ager (1995). All responses were double coded and inter-rater reliability was high (94%). Disagreements were discussed to agreement.

Possible identities

Following the Oyserman and Markus (1990a, 1990b) coding, a school possible identity coded whenever school was mentioned. These responses were the focus of our analyses and by far the most common content, with 67% of all expected possible self content focused on school.4 While most school-focused responses were explicitly about academic performance (e.g., “a good student, getting all A’s”), other aspects of school, particularly school sports and activities (e.g., “on the basketball team”, “participate in school activities”) and social engagement with school (e.g., “close with my teachers”) were also articulated. We coded each component -- ‘academic’ (39.4% of all possible self content), ‘school sports’ (23.6% of all possible self content), and ‘teacher-engagement’ (3.6% of all possible self content). Note that the latter categories require some academic focus (i.e., participation in extracurricular school activities and sports is contingent on maintaining a minimum grade point average and teachers are less likely to befriend marginal and failing students) but differ in the centrality of academic achievement per se. For clarity, we expressed salience as the percentage of possible identities focused on school generally or on academics, school sports, or teacher-engagement specifically as a function of all the possible self content generated by youth (e.g., a youth who generated a total of 4 possible identities, 2 of which were related to school, would receive a school-focused salience score of 50%).

Strategies

Following Oyserman, Gant and Ager (1995, Study 1), we counted each response to the strategy stem following a school-focused possible identity (whether about academics, school-sports or teacher-engagement). The total number of school-focused strategies (e.g., “do all my homework”, “study harder”, or “pay attention to instructions”) youth generated ranged from 0 to 6, M = 1.66, SD = 1.20, only 6% of youth wrote 4 or more strategies. To handle skew, strategy variables were log transformed following the standard procedure of adding 1 to the raw score prior to computing the log. This resulted in the following: total number of school-focused strategies range = 0–1.95, M = 0.87, SD = 0.48, strategies for academic performance range = 0–1.79, M = 0. 58, SD = 0.46, strategies for school-sports and activities range = 0–1.79, M = 0.33, SD = 0.44, and strategies for teacher-engagement range = 0–1.61, M = 0.08, SD = 0.26. We examined the specific content of strategies children wrote for possible sub-group differences in content or detail of strategies, but did not find evidence for qualitative differences in the kind of strategies children wrote. Across family and neighborhood contexts, common strategies were “study every night” and “do all my work”, less common were strategies such as “not talk back to the teacher” and “pay attention to what my teacher says”.

Family socioeconomic status (SES)

Using Hollingshead (1975), the Fast Track Project operationalized family SES as the weighted mean of parent-reported education (weighted by 3) and parent-reported occupation (weighted by 5), with equal weight to both parents if both worked. Parents provided information the year prior to administration of the possible self and strategy measure. SES clustered in the upper end of the “semiskilled laborers” category (range = 3–66, M = 28.9, SD = 13.6) and was below the national average of 43.76 (Rieppi et al., 2002).

Neighborhood disadvantage index (NDI)

Neighborhood-level data -- poverty, unemployment, public assistance, female-headed households, and racial concentration (operationalized as percentage African American), were obtained by geocoding participants’ seventh grade addresses and linking Census tract numbers to data from the 2000 Census. Preliminary analyses indicated that all variables were highly correlated; unemployment was correlated with poverty (r = .88, p < .01), public assistance (r = .83, p < .01), and female-headed households (r = .81, p < .01). A mean of these four variables formed our Neighborhood Disadvantage Index (NDI). NDI scores were then log transformed to reduce skew (M = 2.5, SD = 0.6). We did not include the racial concentration variable in our Neighborhood Disadvantage Index because it was highly correlated with child race (r = .78, p < .01), which was already included as a control variable.

Prior grade point average

Prior grade point average (GPA) from school records obtained the year before possible self and strategy data collection was included in analyses as a control variable. Grades in math, language arts, social studies, and science were coded on a 13-point scale by the Fast Track Project (1= an “F” grade, 13 = an A+ grade, M = 8.0, SD = 3.2, approximately a B-). We computed an average GPA.

Analytic Strategy

Data were analyzed using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM 6.03, Raudenbush, Bryk, & Congdon, 2005) to accommodate the multilevel structure of the data and to examine the extent to which child-level (including parental SES) and neighborhood-level variables predict differences in salience of school-focused possible identities and linked behavioral strategies. HLM allows for explicit modeling of effects at both the individual and neighborhood levels while appropriately adjusting for dependencies among observations for children nested within the same Census tract. In our sample, 4 in 10 (37%) children were nested in Census tracts that contained 5 or more children and 72% of children were nested in Census tracts that contained at least two children. Although there are relatively few children in each of the remaining tracts, HLM is the appropriate statistical framework for the analyses as the large number of tracts (n = 134) provides sufficient statistical power at level 2 (Snijders & Bosker, 1999).

Salience scores were modeled separately as a function of child gender, race, family SES, NDI, and NDI by gender interaction, with prior GPA as a control. Strategy scores were modeled twice, first with an additional control for the salience of the relevant possible identity (e.g., for overall school-focused strategies, we controlled for overall school-focused possible identities while for academic strategies, we controlled for academic possible identities) and second by including two interaction effects, possible identity by family SES and possible identity by NDI.5

Preliminary analyses explored the possibility of a gender by family SES interaction. No effects were found; for parsimony these null effects are not presented in the results section. To facilitate comparison across variables we used standardized coefficients. These were obtained by standardizing all continuous variables prior to entering them into the HLM analysis. Bivariate relationships are detailed in Table 1, Table 2 presents the HLM models predicting salience of possible identities and Table 3 presents the first set of HLM models predicting strategies. Tables 2 and 3 present the size and significance of each predictor variable, controlling for the presence of the other predictor variables. Because Tables 1–3 provide full information we restrict discussion of results to presentation of significant findings. For parsimony, we present the significant interaction effects from the second set of HLM models predicting strategies in the text only and do not provide an additional table.

Table 1.

Correlations among dependent (possible self, strategy), predictor and control variables

| School- focused (total) PI |

Academic PI |

School Sports PI |

Teacher PI |

School- focused Strategies |

Academic Strategies |

School Sports Strategies |

Teacher Strategies |

Male Gender |

White Race |

SES | GPA | NDI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School-focused (total) PI |

1 | ||||||||||||

| Academic PI | .51** | 1 | |||||||||||

| School Sports PI | .41** | −.50** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Teacher PI | .10 | −.14* | −.14* | 1 | |||||||||

| School-focused Strategies |

.43** | .18** | .17** | .23** | 1 | ||||||||

| Academic Strategies |

.27** | .60** | −.37** | −.00 | .64** | 1 | |||||||

| School Sports Strategies |

.24** | −.40** | .71** | −.09 | .50** | −.19** | 1 | ||||||

| Teacher Strategies |

.05 | −.11 | −.12* | .80** | .31** | .01 | −.04 | 1 | |||||

| Male Gender | .08 | .12* | −.01 | −.08 | −.08 | −.05 | .02 | −.12* | 1 | ||||

| White Race | −.13* | −.05 | −.08 | −.03 | −.06 | −.06 | .04 | 0.04 | −.00 | 1 | |||

| SES | .00 | .06 | −.08 | .02 | .16** | .14* | .05 | .06 | .10 | .29** | 1 | ||

| GPA | −.09 | −.08 | −.03 | .05 | .05 | −.01 | .06 | .02 | −.21** | .35** | .32** | 1 | |

| NDI | .22** | .06 | .14 | −.02 | −.01 | −.03 | −.02 | −.01 | −.01 | −.49** | −.36** | −.33** | 1 |

Notes:

Notes: p < .05,

p < .01,

PI = possible identities; School-focused possible identities contain three content foci, these are academic performance-focused possible identities (academic), school sports and activities-focused possible identities (school sports), and teacher-engagement-focused possible identities (teacher); Strategies = Strategies to attain a possible identity; SES = Family Socioeconomic Status, GPA = Grade Point Average; NDI = Neighborhood Disadvantage Index

Table 2.

Effect of child gender and race, family and neighborhood socioeconomic context on salience of school-focused possible identities, controlling for prior grade point average (HLM analyses, Beta coefficients with standard errors)

| Salience of School- Focused Possible Identities (total of academic, sports and activities and teacher engagement) β (SE) |

Salience of Academic- Performance Focused Possible Identities β (SE) |

Salience of School-Sports and Activities Focused Possible Identities β (SE) |

Salience of Teacher- Engagement Possible Identities β (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child and Family | ||||

| Gender (Male) | 0.15 (0.12) | 0.20 (0.13) | −0.02 (0.12) | −0.22 (0.15) |

| Race (White) | −0.07 (0.14) | −0.06 (0.15) | −0.02 (0.15) | −0.03 (0.14) |

| Family SES | 0.09 (0.07) | 0.08 (0.07) | −0.02 (0.07) | 0.02 (0.06) |

| Prior Year GPA | −0.02 (0.07) | −0.02 (0.07) | −0.00 (0.07) | 0.01 (0.89) |

| Neighborhood | ||||

| Disadvantage Index | 0.26 (0.09)** | 0.04 (0.09) | 0.15 (0.09) | 0.15 (0.14) |

| Disadvantage X Gender | −0.06 (0.12) | −0.02 (0.12) | 0.02 (0.12) | −0.28 (0.15)† |

Notes: Salience is the percentage of all possible self content that includes the particular possible identity (school overall or each component). For ease, statistically significant and trend level significant results are bolded.

p < .01,

p < .10.

Table 3.

Effect of child gender and race, family and neighborhood socioeconomic status on strategies to attain school-focused possible identities, controlling for possible identity salience and prior grade point average (HLM analyses, Beta coefficients with standard errors)

| Number of School- Focused Strategies (overall) β (SE) |

Number of Academic- Performance Focused Strategies β (SE) |

Number of School-Sports and Activities Focused Strategies β (SE) |

Number of Teacher- Engagement Strategies β (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child and Family | ||||

| Gender (Male) | −0.24 (0.11)* | −0.27 (0.11)* | 00.07 (0.09) | −0.18 (0.09)* |

| Race (White) | −0.11 (0.13) | −0.16 (0.11) | 0.09 (0.10) | −0.07 (0.08) |

| Family SES | 0.16 (0.06)** | 0.12 (0.05)* | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.09 (0.03)* |

| Prior Year GPA | 0.02 (0.06) | −0.00 (0.05) | 0.03 (0.05) | −0.04 (0.04) |

| Possible Identity Salience | 0.44 (0.05)** | 0.64 (0.05)** | 0.72 (0.04)** | 0.78 (0.04)** |

| Neighborhood | ||||

| Disadvantage Index | 0.00 (0.08) | 0.02 (0.07) | −0.04 (0.07) | −0.01 (0.08) |

| Disadvantage * Gender | −0.21 (0.10)* | −0.18 (0.10) | −0.06 (0.09) | 0.05 (0.09) |

Notes: For ease, statistically significant effects are presented in bold,

p < .01,

p < .05,

< .10

Results

Bivariate Associations

Correlations among dependent (possible identity salience, strategy) and predictor variables are presented in Table 1. We inspected the relevant bivariate associations, finding modest associations that did not preclude simultaneous inclusion of all the predictor and control variables in the model. Specifically family SES correlated modestly with neighborhood deprivation index (NDI, r = −.36, p < .01), prior year GPA (r = −.33, p < .01) and child race (dummy coded as white vs. other) (r = .29, p < .01). Neighborhood deprivation (NDI) also correlated modestly with prior year GPA (r = .32, p < .01) and race (r = −.49, p < .01). Prior year GPA correlated modestly with gender (dummy coded as male vs. other) (r = −.21, p < .01) and race (r = .35, p < .01).

Predictors of Possible Identity Salience

We first examined the hypothesized main and interaction effects of family SES and neighborhood disadvantage (NDI) on the salience of school-focused possible identities overall and then by specific content category (academics, school-sports, teacher-engaged). Results are detailed in Table 2, with the total school-focused salience variable presented at the left, followed by the salience of specific contents of school-focused possible identity variables. We found one main effect, neighborhood disadvantage (NDI β = 0.26, SE = 0.09, p < .01) predicted salience of school-focused possible identities. Youth living in neighborhoods with greater economic disadvantage were more likely to have school-focused possible identities. Looking at the effect of NDI on salience of each of the specific school-focused possible identity content domains, we found an interaction effect of gender and NDI for possible identities focused on teacher engagement, which was significant at trend-level, (β= −0.28, SE = 0.15, p = .06). The salience of school-focused possible identities describing teacher-engagement was lower (at trend-level) among boys from more economically disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Predictors of Strategies

Next, we examined the hypothesized main and interaction effects of gender and socioeconomic deprivation on the number of strategies youth generated for attaining their school-focused possible identities overall and by specific content domain. First, we examined these effects controlling for the salience of school-focused possible identities, as detailed in Table 3. The first column on the left presents results for the total school-focused possible identity strategy count variable and in the next columns are results for strategies to attain each of the three specific school-focused possible identity components. As can be seen, gender and family SES predicted students’ number of school-focused strategies. Boys were less likely to generate strategies than girls (β = −0.24, SE = 0.11, p < .05) and this effect was also found for strategies to attain possible identities specifically focused on academic performance (β = −0.27, SE = 0.11, p < .05) and teacher-engagement (β = −0.18, SE = 0.09, p < .05). Moreover, even in this relatively low SES sample in which average SES corresponded to semiskilled labor, higher SES children were more likely to have school-focused strategies overall (β = 0.16, SE = 0.06, p < .01). This effect was also found for strategies to attain possible identities specifically focused on academic performance (β = 0.12, SE = 0.05, p < .05) and teacher-engagement (β = 0.09, SE = 0.03, p < .05).

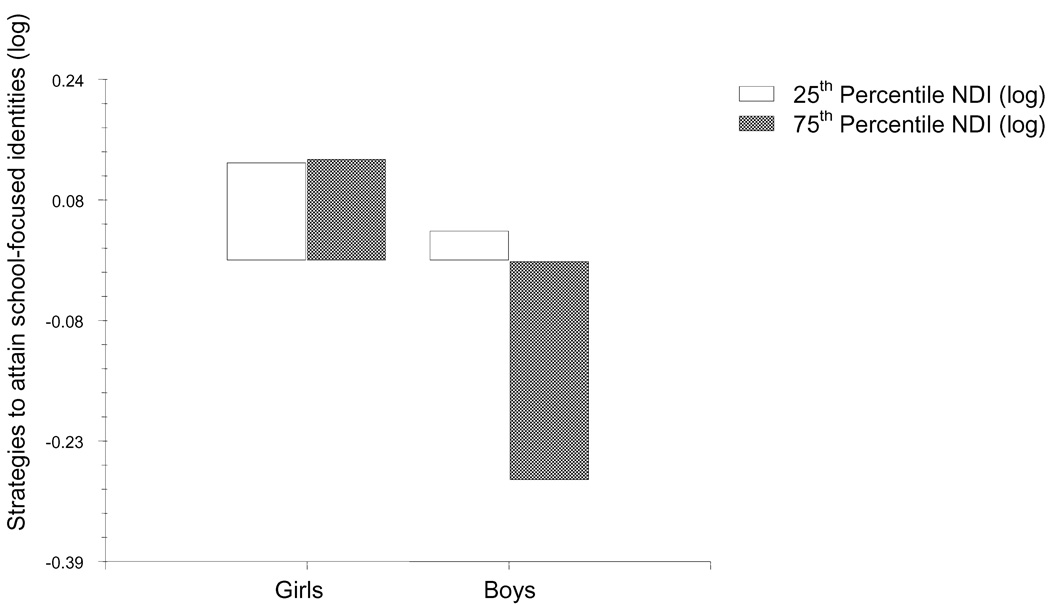

A significant neighborhood deprivation by gender effect was also found for the overall number of school-focused strategies generated (β = −0.21, SE = 0.10, p = .05). We examine this interaction graphically in Figure 1. As can be seen, boys living in more economically disadvantaged neighborhoods have fewer strategies to attain their school-focused possible identities. Neighborhood disadvantage has no such negative effect on girls. To clarify this pattern, we separately estimated regression models for boys and girls, finding that neighborhood disadvantage was not significantly associated with girls’ school-focused strategies (β = 0.06, SE = 0.09, p = .49), but was significantly and negatively associated with boys’ school-focused strategies (β = −0.26, SE = 0.09, p < .01). Thus, findings suggest that neighborhood disadvantage has more of an undermining effect on boys’ ability to generate strategies to attain their school-focused possible identities than it does on girls’ ability to generate such strategies.

Figure 1.

Differential effect of neighborhood disadvantage on strategies for attaining school-focused possible identities by gender and level of disadvantage: displayed at low (25th percentile) and high (75th percentile) levels of disadvantage

Notes: Standardized effects are presented. NDI = Neighborhood Disadvantage Index; graph displays the relationship between child gender and level of neighborhood disadvantage based on the final HLM analytic results.

Next, we considered whether either neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation or family SES moderates the relationship between school-focused possible identities and strategies. One statistically significant interaction effect was found at the neighborhood level, neighborhood disadvantage moderates the relationship between possible identities and strategies for engaging in school-sports and extracurricular activities (β = −0.11, SE = 0.05, p < .05). Two statistically significant interaction effects were found at the family level, family socioeconomic status moderates the relationship between possible identities and strategies for engaging in school-sports and extracurricular activities (β = 0.18, SE = 0.04, p < .01) and the relationship between possible identities and strategies focused on engaging teachers and principals (β = 0.21, SE = 0.03, p < .01). In each case, socioeconomic disadvantage undermines the relationship between the salience of a possible identity and the number of strategies youth generate to work toward the identity.

Discussion

Prior literature has conceptualized possible selves in general and school-focused possible identities and strategies in particular as independent variables that predict youth outcomes (for a review, Oyserman & Fryberg, 2006). Across a variety of methods (cross-sectional correlational, longitudinal, experimental and intervention research) positive effects of school-focused possible identities on academic outcomes have been demonstrated even in low-income neighborhoods when these identities are linked with behavioral strategies or in other ways made to feel proximal (for a review, Oyserman & Destin, in press). The current study takes a different perspective, treating possible identities and behavioral strategies as dependent variables, and examining the extent to which family SES and neighborhood economic disadvantage predict differences in school-focused possible identities and behavioral strategies. While research on the effects of disadvantage on children’s outcomes has examined either family or neighborhood effects (and therefore is vulnerable to the possibility of confounding one with the other), we include both in our model, allowing us to distinguish between unique effects of family and neighborhood context in a relatively disadvantaged sample. Because prior research suggests that all children have high educational aspirations, we were particularly interested in the undermining effect of socioeconomic deprivation at the neighborhood-level as well as at the family-level on the strategies children had to attain their school-focused possible identities.

We found that children in more disadvantaged neighborhoods were more likely to have school-focused possible identities than children in less disadvantaged neighborhoods, implying that educational attainment was at least as salient as an important destination for these children compared to others in the sample. However, we also found that both family and neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage predicted having fewer strategies to attain school-focused possible identities, implying that socioeconomic disadvantage undermines children’s ability to clearly see the path toward their school-focused aspirations. In our sample, average parental occupation and education was equivalent to that of a semi-skilled laborer, yet even in this sample, higher family SES predicted more strategies to attain school-focused possible identities both overall and for possible identities focused on academic attainment and teacher-engagement in particular. Moreover, when the interaction between family SES and possible identities was added to the equation, we found that family SES moderated the relationship between strategies and possible identities, such that only children from relatively higher SES families had strategies to attain salient school sports and activities and teacher-engagement focused possible identities.

We also found two separate effects of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage on strategies. First, congruent with our hypothesis that boys may be more vulnerable to the undermining effect of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage on strategies to attain elements of one’s possible self, boys in our sample who lived in more disadvantaged neighborhoods generated fewer strategies to attain their school-focused possible identities. Second, neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage undermined the relationship between content of possible self and strategies such that children from more economically disadvantaged neighborhoods had fewer strategies to attain their school-activities focused possible identities even if these aspects of their possible self were quite central and salient to them.

The current study takes a first step in demonstrating that family SES and neighborhood economic disadvantage affect youth academic outcomes by influencing whether school-focused possible identities are linked with behavioral strategies. Clearly, future longitudinal research is needed to show the full mediated pathway and the size of the effect over time. For example, neighborhood disadvantage may matter more as children move from elementary school to middle and then to high school and require more sophisticated behavioral strategies to attain their school-focused possible identities. Moreover, linking neighborhood economic disadvantage to peer networks would allow for analyses of the pathways through which gender differences occur.

Our dataset did not allow for demonstration of the full meditational pathway from neighborhood and family to academic outcomes via possible identities and strategies. However, because our analyses separately examined the effects of disadvantage on possible identities and on behavioral strategies, we are able to specify how family-level and neighborhood-level disadvantage separately affect children’s possible identities and strategies. Our results demonstrate that even among children living in low-income neighborhoods, both the family-level and the neighborhood-level disadvantage matters. Each separately undermines the likelihood that children will have behavioral strategies to attain their school-focused possible identities. While we also find neighborhood effects, our results demonstrate that family SES is particularly important when considering strategies to attain school-focused possible identities. Children growing up with parents with more education and occupational prestige are more likely to have strategies to attain their academic-achievement focused and their teacher-engagement focused possible identities. These are the strategies most likely to lead to academic achievement. Note that our sample was of lower socio-economic status than the U.S. national average, with the average being semi-skilled labor. Even at this lower end of the spectrum, as parental education and occupational status increase, parents may be more able to model specific strategies – for example continued effort and getting along with teachers and others at school, which can support students’ academic efforts. These results imply that efforts to involve parents in school are especially likely to help by modeling strategies to achieve academic success in school.

Children living in disadvantaged neighborhoods expressed at least as many school-focused possible identities as did other children. They were more, not less, likely to have some form of school-focused possible identity. These results are congruent with the high aspirations noted in national samples (Mello, 2009; Trusty, 2000) and suggest that even as disadvantage increases, doing well in school is still a salient component of children’s possible self. Economically disadvantaged children care about school, but are less likely than more advantaged children to have salient behavioral strategies to make their school-focused possible identities come to fruition. Behavioral strategies are important because they cue immediate action to attain the possible identity, without them, a school-focused possible identity may feel farther in the future and less likely to require immediate action.

Children living in disadvantaged neighborhoods are also less likely to benefit from neighborhood-level focus on strategies (e.g. set homework times or enforcement of limits to television time) that benefit all children when they are collective norms (for general discussions see Sampson, 1997; Wilson, 1987). A number of studies suggest that children of low-education and low-income parents are especially likely to turn to alternative models such as television sports and entertainment models (King & Multon, 1996). These models may inspire lofty goals, but they do not articulate a path to school success. Indeed, experimental evidence demonstrates that children in low-income neighborhoods assume that the path to college is closed unless primed to think of it as open (Destin & Oyserman, 2009). In two studies, Destin and Oyserman (2009) demonstrate that low income children as young as twelve years of age plan to work more on their homework when primed to think of the path to college as open due to financial aid compared to a control condition or a condition in which the cost of college is made salient. Family and/or neighborhood role models can “open” the path to college by modeling how to get needed grades and funding. A follow-up experiment replicates this effect when low income children are primed to think of their future as education-dependent (contingent on how well they do in school now) rather than education independent (Destin & Oyserman, 2010). Here too, children plan to work harder and spend more time on homework when school-work provides a path to success.

We found that the effect of neighborhood disadvantage on strategies was moderated by gender. In more economically disadvantaged neighborhoods, boys reported fewer strategies to achieve their school-focused possible identities than did girls. These results suggest that prior findings of lower goal-setting in males, especially low-income males (Massey, Gebhardt & Garnefski, 2008; Mello & Swanson, 2007), may actually be due to a lack of behavioral strategies, rather than a lack of future self-images focused on school. Our results suggest some reasons that boys may fail. First, boys regardless of neighborhood and family disadvantage had fewer behavioral strategies to attain school-focused possible identities. Second, boys from more disadvantaged neighborhoods were less likely to have behavioral strategies to attain their school-focused possible identities. These gender differences are compounded by the fact that both boys and girls in socioeconomically economically disadvantaged neighborhoods tended to have more school-sports and activities focused possible identities. While generally focused on school, sports and activities-based possible identities may be insufficient to focus attention and resources on academics per se.

To understand why boys might be more sensitive to neighborhood context effects, we turned to research on gender differences in peer relationships (see Rose & Rudolph, 2006 for a comprehensive review). Early adolescent boys’ peer networks tend to be larger than girls and relied on for fun, social status and hierarchy ranking (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Sports may fulfill status and hierarchy purposes for boys, while other kinds of engagement with school may fail to do so, especially when adult male role models who would focus boys’ attention on school as a way to attain social status are lacking. Clearly, future research is needed to expose the processes by which neighborhood and family disadvantage specifically targets the strategies of boys to attain their school-focused possible identities. One possibility that we were not able to separately test is that boys in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to lack employed same sex role models than girls, both in their own home and in the homes of their neighbors. As we noted in the measures section, we could not separately test for the effect of father presence because neighborhood female-headed household correlated 0.81 with neighborhood unemployment. However, boys may be especially likely to lack gender-matched role models because teachers are more likely to be female (Dee, 2007) and households are more likely to be female-headed (see Zirkel, 2002 for evidence that gender-match of role models may matter).

Taken together our results converge with other reports that children in low-income contexts do envision possible identities of succeeding in school. Our results provide some insight into the process by which these high expectations fail to turn into educational success: children see the destination but not the path. Not seeing the path is particularly likely for children living in relatively more disadvantaged neighborhoods and in lower SES families. These children are less likely to have academic-performance or teacher-engagement focused strategies. A number of implications flow from our finding that disadvantaged children see the destination but not the path. First, our findings counter a common assumption is that low-income students require help in raising their expectations and setting ambitious long-term goals. Rather, our results suggest these students do see school as a goal, they need help seeing the path and would be better served by interventions that focus on linking their salient school-focused possible identities to behavioral strategies to attain these goals.

Acknowledgment

Funding for this work came in part from a program project within the African American Mental Health Research Program NIH P01 – MH58565 (James Jackson PI) and from the NIH Prevention Research Training Program (NIH T32 MH63057-03, Oyserman PI) in which Johnson and James were Fellows. We would like to thank Nick Yoder for help coding the possible-self data, the Fast Track and Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group for allowing us to use their possible self and neighborhood data and Michael Foster for providing details about the sampling process and sample retention in the Fast Track. The Fast Track project was funded by National Institute of Mental Health Grants R18 MH48043, R18 MH50951, R18 MH50952, and R18 MH5095, and includes, in alphabetical order: Karen L. Bierman, John D. Coie, Kenneth A. Dodge, Mark T. Greenberg, John E. Lochman, Robert J. McMahon, and Ellen E. Pinderhughes.

Footnotes

We focus on socioeconomic context rather than racial-ethnic identity context. Racial and ethnic heritage are often highly correlated with both family and neighborhood socioeconomic context variables, making separate estimation of effects effectively impossible. Moreover, there is some evidence that family and neighborhood contexts are the more important factors in predicting adolescent goal-setting (Massey et al, 2008). For example, longitudinal analyses of national data of children aged 14–26 (Mello, 2009, using the 1988 National Educational Longitudinal Study - NELS) shows effects for family SES on occupational and educational expectations controlling for race-ethnicity and few effects of race-ethnicity controlling for SES. Using a separate sample of adolescents from five ethnic groups, Phinney and colleagues (2001) found that after controlling for SES, there was no association between ethnicity and reported long-term goals and expected outcomes.

That this study focused only on boys and conflated race and SES is important for a number of reasons. In some studies, stronger neighborhood effects are found for boys than for girls when neighborhood SES is high (Connell & Halpern-Felsher, 1997; Duncan 1994; Ensminger et al., 1996; Ludwig, Duncan, & Hirschfield, 2001). Some studies also find effects by race-ethnicity, with stronger neighborhood effects on outcomes of European American compared to African American youth (Brooks-Gunn et al., 1993; Duncan, 1994; Halpern-Felscher et al., 1997). Taken together, these studies imply that the Cook (Cook et al., 1996) findings were more due to the positive effects of SES on the white middle class boys than to the negative effects of SES on the African American low-income boys.

Sample attrition was low, with 86% of the initial normative sample participating in the 8th grade possible self and strategy interview. Likelihood of participation in this interview did not vary as a function of race, gender, geographic location, or baseline measures of problem behaviors used to screen the children (χ2 = 5.36, df = 7, p = .62) (E.M. Foster, personal communication, February 18, 2006). Excluded from current analyses were the 34 youth with missing data on the possible self and strategies questions or on family or neighborhood socioeconomic measures, or grades.

Other categories were much less common, 17% of responses focused on peer relationships, 8% focused on personality traits, 5% focused on physical appearance or health, 2% were focused on off-track outcomes such as being involved with drugs, and 1% were focused on lifestyle or material possessions.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this additional control, which allows us to examine the effect of socioeconomic context on strategies separate from the dependence of strategies on having a possible identity in the domain of school.

Contributor Information

Daphna Oyserman, University of Michigan.

Elizabeth Johnson, University of Tennessee.

Leah James, University of Michigan.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson D. Sibling estimates of neighborhood effects. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan G, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood poverty: Vol. 2. Policy implications in studying neighborhoods. New York: Russell Sage; 1997. pp. 80–93. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan G, Klebanov P, Sealand N. Do neighborhoods influence child and adolescent development? American Journal of Sociology. 1993;99:353–395. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. A developmental and clinical model for the prevention of conduct disorders: The Fast Track Program. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:509–527. [Google Scholar]

- Cook T, Church M, Ajanaku S, Shadish W, Kim J, Cohen R. The development of occupational aspirations and expectations among inner-city boys. Child Development. 1996;67:3368–3385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran M, Gordon R, Laren D, Solon G. The association between men's economic status and their family and community origins. Journal of Human Resources. 1992;27:575–601. [Google Scholar]

- Crowder K, South SJ. Neighborhood distress and school dropout: The variable significance of community context. Social Science Research. 2003;32:659–698. [Google Scholar]

- Dee T. Teachers and the gender gaps in student achievement. Journal of Human Resources. 2007;42:528–554. [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo D, Forgatch M, Martinez C. Parenting of divorced mothers as a link between social status and boys' academic outcomes: unpacking the effects of socioeconomic status. Child Development. 1999;70:1231–1245. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destin M, Oyserman D. From assets to school outcomes. Psychological Science. 2009;20:414–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destin M, Oyserman D. Incentivizing education: Seeing schoolwork as an investment, not a chore. Manuscript under editorial review. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornbusch S, Ritter P, Steinberg L. Community influences on the relation of family statuses to adolescent school performance: Differences between African Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites. American Journal of Education. 1991;99:543–567. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ. Families and neighbors as sources of disadvantage in the school decisions of White and Black adolescents. American Journal of Education. 1994;103:20–53. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J, Wigfield A. Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:109–130. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger ME, Lamkin R, Jacobson N. School leaving: A longitudinal perspective including neighborhood effects. Child Development. 1996;67:2400–2416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle D, Alexander K, Olson LS. The gender gap in math: Its possible origins in neighborhood effects. American Sociological Review. 1994;59:822–838. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern-Felsher B, Connell J, Spencer MB, Aber JL, Duncan G, Clifford E, Crichlow WE, Usinger PA, Cole SP, Allen L, Seidman E. Neighborhood and family factors predicting educational risk and attainment in African American and White children and adolescents. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan G, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood Poverty: Context and Consequences for Children. Volume 1. New York: Russell Sage; 1997. pp. 146–173. [Google Scholar]

- King M, Multon K. The effects of television role models on the career aspirations of African American junior high school students. Journal of Career Development. 1996;23:111–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig J, Duncan G, Hirschfield P. Urban Poverty and juvenile crime: Evidence from a randomized housing-mobility experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1998;116:655–679. [Google Scholar]

- Mason C, Cauce A, Gonzales N, Hiraga Y. Adolescent problem behavior: The effect of peers and the moderating role of father absence and the mother-child relationship. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1994;22:723–743. doi: 10.1007/BF02521556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey E, Gebhardt W, Garnefski N. Adolescent goal content and pursuit: A review of the literature from the past 16 years. Developmental Review. 2008;28:421–460. [Google Scholar]

- Mello Z. Racial/ethnic group and socioeconomic status variation in educational and occupational expectations from adolescence to adulthood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2009;30:494–504. [Google Scholar]

- Mello Z, Swanson D. Gender differences in African American adolescents' personal, educational, and occupational expectations and perceptions of neighborhood quality. Journal of Black Psychology. 2007;33:150–168. [Google Scholar]

- Mercy J, Steelman L. Familial influence on the intellectual attainment of children. American Sociological Review. 1982;47:532–542. [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson RA. The attitude-achievement paradox among black adolescents. Sociology of Education. 1990;63:44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Orfield G, Losen D, Wald J, Swanson C. Losing our future: How minority youth are being left behind by the graduation rate crisis. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Orfield G. Dropouts in America: Confronting the graduation rate crisis. Harvard University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Bybee D, Terry K. Possible selves and academic outcomes: How and when possible selves impel action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:188–204. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.1.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Fryberg SA. The possible selves of diverse adolescents: Content and function across gender, race and national origin. In: Dunkel C, Kerpelman J, editors. Possible selves: Theory, research, and applications. Huntington, NY: Nova; 2006. pp. 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Bybee D, Terry K, Hart-Johnson T. Possible selves as roadmaps. Journal of Research in Personality. 2004;38:130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Gant L, Ager J. A socially contextualized model of African American identity: Possible selves and school persistence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:1216–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, James L. Identity-based motivation and the future self: Content and consequences of possible identities. In: Schwartz S, Luyckx K, Vignoles V, editors. Handbook of Identity Theory and Research. Springer-Verlag; pp. 00–00. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Markus H. Possible selves and delinquency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990a;59:112–125. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Markus H. Possible selves in balance: Implications for delinquency. Journal of Social Issues. 1990b;46:141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Saltz E. Competence, delinquency, and attempts to attain possible selves. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:360–374. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Terry K, Bybee D. A possible selves intervention to enhance school involvement. Journal of Adolescence. 2002;25:313–326. doi: 10.1006/jado.2002.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parcel T, Dufur M. Capital at home and at school: Effects on student achievement. Social Forces. 2001;79:881–912. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J, Baumann K, Blanton S. Life goals and attributions for expected outcomes amongst adolescents from five ethnic groups. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2001;23:363–377. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Congdon R. Hierarchical Linear Modeling (Version 6.0) [Computer software] Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rieppi M, Laurence L, Greenhill, Ford R, Chuang S, Wu M, Davies M, Abikoff H, Wigeal T. Socioeconomic status as a moderator of ADHD treatment outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:269–277. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose A, Rudolph K. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. Collective regulations of adolescent misbehavior: Validation results from eighty Chicago neighborhoods. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1997;12:227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Scarr S, Weinberg R. The influence of "family background" on intellectual attainment. American Sociological Review. 1978;43:674–692. [Google Scholar]

- Seignor R. Future orientation: Developmental and ecological perspectives. NY: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Segal H, DeMeis D, Wood G, Smith H. Assessing future possible selves by gender and socioeconomic status using the anticipated life history measure. Journal of Personality. 2001;69:57–87. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel analysis. An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Trusty J. High educational expectations and low achievement: Stability of educational goals across adolescence. The Journal of Educational Research. 2000;93:356–365. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace J, Muroff J. Preventing substance abuse among African American children and youth: Race differences in risk factor exposure and vulnerability. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2002;22:235–261. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Zirker S. Is there a place for me? Role models and academic identity among white students and students of color. Teachers College Record. 2002;104:357–376. [Google Scholar]