Abstract

The complement system is a critical component of innate immunity that requires regulation to avoid inappropriate activation. This regulation is provided by many proteins, including complement factor H (CFH), a critical regulator of the alternative pathway of complement activation. Given its regulatory function, mutations in CFH have been implicated in diseases such as age-related macular degeneration and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, and central nervous system diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and a demyelinating murine model, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). There have been few investigations on the transcriptional regulation of CFH in the brain and CNS. Our studies show that CFH mRNA is present in several CNS cell types. The murine CFH (mCFH) promoter was cloned and examined through truncation constructs and we show that specific regions throughout the promoter contain enhancers and repressors that are positively regulated by inflammatory cytokines in astrocytes. Database mining of these regions indicated transcription factor binding sites conserved between different species, which led to the investigation of specific transcription factor binding interactions in a 241 base pair (bp) region at −416 bp to −175 bp that showed the strongest activity. Through supershift analysis it was determined that c-Jun and c-Fos interact with the CFH promoter in astrocytes in this region. These results suggest a relationship between cell cycle and complement regulation, and how these transcription factors and CFH affect disease will be a valuable area of investigation.

Keywords: Complement, Complement Factor H, astrocyte, c-Jun, c-Fos, transcription

1. Introduction

The complement cascade is an inflammatory response of the innate immune system, made up of three pathways. These pathways are the classical, mannose-binding lectin (MBL) and alternative complement cascades. Despite different forms of initiation, all three pathways converge at the central C3 convertase molecule. At this point in the complement cascade, inflammatory cell recruitment, opsonization, and cell lysis are initiated. Specific proteins for each pathway regulate the complement system at multiple points along the cascade, which is crucial to prevent damage to host tissues from unnecessary inflammatory activation.

Even if complement is initially activated by the classical or MBL pathway, the alternative pathway can account for 80–90% of total complement activation (Harboe et al., 2004), due to the feedback loop or ‘tickover’ of C3b deposition that in turn creates more C3 convertases. This suggests that the regulation of the alternative pathway is critical for avoiding inappropriate complement activation. The primary regulatory protein of the alternative pathway is complement factor H (CFH), the main discriminator between foreign and host cell surfaces. It is a soluble 155 kiloDalton (kDa) protein with multiple binding sites for heparin and C3b (Meri and Pangburn, 1990), which aid in its ability to differentiate host and foreign particles and facilitate its role as cofactor for factor I (CFI), respectively (Whaley and Ruddy, 1976a). With CFH bound to C3b, factor B is prevented from binding to C3b and forming the alternative pathway C3 convertase, C3bBb (Weiler et al., 1976). CFI can then cleave C3b and form inactive C3b fragments. Additionally, CFH has its own C3 convertase decay accelerating factor activity to further prevent more C3 convertase from forming (Sim et al., 1986; Weiler et al., 1976; Whaley and Ruddy, 1976b).

CFH is also known to hold other functions as well; in addition to regulating the alternative pathway of complement activation, studies indicate that it also can inhibit the classical pathway (Ajona et al., 2007) by its cofactor ability to aid in the inactivation of C3b after binding by CFH (Ollert et al., 1995) or by blocking C1q binding to anionic phospholipids, an antibody-independent route of classical activation (Tan et al., 2011). CFH also functions in immune cell recruitment (Mihlan et al., 2009), chemotaxis for monocytes (Imamura et al., 1992; Kim et al., 2009; Nabil et al., 1997; Strohmeyer et al., 2002), cell signaling (DiScipio et al., 1998) and adhesion as a ligand for L-selectin (Malhotra et al., 1999) or through a potential CFH receptor on polymorphonuclear leukocytes (Avery and Gordon, 1993; Dierich et al., 1987). These studies indicate the significant value of CFH as an important component of innate immunity.

While the liver is known to be a primary source for many complement proteins, all of the effector and regulatory complement proteins in the complement cascade are known to be produced locally in the central nervous system (CNS) by glial cells and neurons (Gasque et al., 1993; Gasque et al., 1992; Gordon et al., 1992). This local production thus contributes to the immune system’s homeostasis. However, which cells produce which complement proteins is not widely known.

Glial cells are the resident brain cells, made up of astrocytes, oligodendrocytes and microglia, which all can possess dendritic processes that branch out from the cell body. Astrocytes are the largest glial cell and make up a portion of the structure of the blood brain barrier which protects the brain from immune components that could be potentially damaging. They also have numerous other roles, such as in metabolism and synaptic function (Panickar and Norenberg, 2005; Schousboe et al., 1977). All of these functions are not surprising when it has been determined that due to their highly branched processes, one astrocyte can make as many as 30,000 connections with neighboring cells (Smith, 2010), which also aids in the proposed antigen-presenting cell function (Constantinescu et al., 2005; Fierz et al., 1985; Fontana et al., 1984; Girvin et al., 2002). Oligodendrocytes produce and maintain the myelin that lines the axons of the neurons. It is thought that the destruction of these cells is a primary contributor in many demyelinating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis (Lucchinetti et al., 2000). Lastly, microglia are the glial immune system component and the tissue equivalent of macrophages. They possess phagocytic function important in clearing debris from cell lysis as well as from normal apoptotic events (Perry et al., 1985). These cells also have a role in antigen presentation and inflammatory cell recruitment (Bo et al., 2003; Charo and Ransohoff, 2006; Hickey and Kimura, 1988).

Astrocytes and microglia are known to produce a number of inflammatory cytokines (Benveniste et al., 1994; Benveniste et al., 1990; Iwama et al., 2011), and CFH production and activity can be affected by cytokines that are present in inflammatory situations, such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-lβ and IL-6, and also by LPS stimulation (Ault et al., 1997; Brooimans et al., 1990; Buhe et al., 2010; Minta, 1988; Munoz-Canoves et al., 1989). It follows that diseases that invoke these cytokine responses from the immune system might alter CFH production. Despite the upregulation or mutations of CFH in many diseases involving the CNS, little is known about how CFH functions in the CNS.

CFH promoter and gene polymorphisms have been associated with a number of immune-mediated diseases, including atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (Caprioli et al., 2003; Perez-Caballero et al., 2001), membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis type II (Pickering et al., 2002), and recently, systemic lupus erythematosus (Bao et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2011). In addition to that, CFH has been shown to be involved in diseases affecting the brain and CNS, including age-related macular degeneration (Hageman et al., 2005; Klein et al., 2005), Alzheimer’s (Strohmeyer et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2011), and Parkinson’s disease (Wang et al., 2011). This non-exhaustive list underscores the far-reaching range of CFH activity throughout the body, and thus indicates the importance of understanding its regulation and function.

Little research has been completed on the regulation of CFH, especially in the brain. With the knowledge that CFH is often induced in pathological conditions, is significant in certain diseases, and is potentially protective in the demyelinating disease model experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (Griffiths et al., 2009), it is important to investigate the roles CFH transcriptional regulation plays in the CNS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Glial cell lines and enrichment of glial cultures

The murine astrocyte 2.1 (Ast 2.1) cell line was obtained from Scott Zamvil (Soos et al., 1998). Primary astrocytes as well as microglia and oligodendrocytes were harvested from one to three-day old C57BL/6 mouse pups as described (Hellendall and Ting, 1997; McCarthy and de Vellis, 1980). Briefly, the brains of 1–3-day-old mice were dissected, the meninges were removed and cells were dissociated in trypsin-EDTA. Mixed glial cells were cultured for 10–14 days after which microglial precursors were mechanically separated by shaking at 160 rpm for one hour at 37°C and then allowed to adhere to non-tissue culture treated plastic, grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 0.5% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen). The microglial population was >90% CD-11b positive by FACS analysis, with astrocytes being the contaminating cell source (data not shown). Oligodendrocyte and astrocyte precursors were shaken at 225 rpm at 37°C overnight and oligodendrocyte precursors were collected in the supernatant and grown on poly-D-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) treated plates in DMEM supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 10% fetal bovine serum, N-2 and T-3 supplements (Invitrogen) and platelet-derived growth factor (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ). Astrocyte precursors were treated with trypsin-EDTA and cultured on new plates in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Enriched astrocytes were >95% GFAP positive by FACS analysis, with the remainder of the cells being mixed glia of unknown origin (data not shown). All animals were housed in the Laboratory of Animal Resources facilities at Iowa State University and all mouse protocols were approved by Iowa State University Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

RNA was isolated from primary glial cells using the Trizol liquid samples reagent (Invitrogen). For PCR reactions, primers were designed for the murine CFH gene and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), as shown in Table 1. Utilizing 200–400 ng RNA from glial cells, RT-PCR was performed using the Superscript One-step RT-PCR enzyme mix with platinum Taq (Invitrogen). At three cycle intervals, samples were removed and run on a 1% agarose gel, starting at cycle 21 and continuing through cycle 30. Cycling set was as follows: 94°C for 15s, 60°C for 30s, 68°C for 35s.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides

| GAPDH sense | AAGAGGAACATCGTGGTAAAG |

| GAPDH antisense | AAGGATGAAGGAAGTGATTTG |

| CFH sense | ATGTCACTTGTTCTCCTGTCC |

| CFH antisense | AGAGATTCCATTGAGTCCAGC |

| CFH RACE | AGATCCAACTGCCAGCCTAAAGGACCC |

| 597 bp sense | GGCTAGCCCTGCTTCCCTACCCAC |

| 416 bp sense | GGCTAGCATGACAATCTTTTCAAC |

| 250 bp sense | GGCTAGCCCTTGCTCACATTTCCAG |

| 71 bp sense | GGCTAGCAATCCTGATTTCCTAAAC |

| pGL2 antisense | ATCTCGAGGTCACAGCAGGG |

| Mutagenesis Sp-1sense | TTGGTCCTGAAAACACACCTAACTGAAGTTC |

| Mutagenesis Sp-1antisense | GAACTTCAGTTAGGTGTGTTTTCAGGACCAA |

| Mutagenesis AML-1/Cebp/β sense | CATGCTTTCTGTTCTGTCCATTGTCCACAG |

| Mutagenesis AML-1/Cebp/β antisense | CTGTGGACAATGGACAGAACAGAAAGCATG |

| Mutagenesis GATA-1 sense | AAAGGATTATGCCCTCCAGCCCTTGCTC |

| Mutagenesis GATA-1 antisense | GAGCAAGGGCTGGAGGGCATAATCCTTT |

| EMSA sense | CTTCATGCTTTCTGTTCTGTGGTTTGTCCACAGTAGAACACAATTTAAAGGATT |

| EMSA antisense | AATCCTTTAAATTGTGTTCTACTGTGGACAAACCACAGAACAGAAAGCATGAAG |

| EMSA mutant sense | CTTCATGCTTTCTGTTCTGTCCATTGTCCACAGTAGAACACAATTTAAAGGATT |

| EMSA mutant antisense | AATCCTTTAAATTGTGTTCTACTGTGGACAATGGACAGAACAGAAAGCATGAA |

2.3. Western blot

Primary astrocytes and ast 2.1 cells were maintained in the absence of serum for 24 hours prior to experimentation. Aftewards, primary liver, primary astrocyte, and ast 2.1 cell line samples were homogenized in RIPA buffer, maintained at 4°C throughout, and measured for concentration using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, ThermoFisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) and Protein Assay reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The samples were loaded onto Nupage Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris Gels (Invitrogen) under reducing conditions at a 40 μg concentration per sample for two hours at 200 volts. The gel was transferred onto Immobilon (Millipore, Billerica, MA) membranes in the X-cell Sure Lock (Invitrogen) tank blotting system for two hours at 30 volts. The blot was then blocked for an hour in 5% dry milk in 1X TBS with 0.1%Tween and stained overnight with goat anti-human CFH (Quidel, San Diego, CA) primary antibody at 1:750 dilution in 5% dry milk in 1X TBS with 0.1% Tween at room temperature. The following day, the secondary antibody HRP-rabbit anti-goat IgG (Invitrogen) and HRP-conjugated anti-biotin (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) was administered at 1:1000 for an hour at room temperature in 5% dry milk in 1X TBS with 0.1%Tween. The blot was washed in 1X TBS with 0.1%Tween, developed with the Lumiglo detection reagent (Cell Signaling) and viewed on the mini LAS 4000 Imaging System (General Electric Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ).

2.4. Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE)

RNA previously isolated from primary astrocytes, microglia and liver tissue via the Trizol liquid samples reagent (Invitrogen) was utilized in a RACE reaction utilizing a primer shown in Table 1 via the SMARTer RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). cDNA was then cloned into the pCR2.1-TOPO plasmid (Invitrogen), plasmid prepped for DNA extraction (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and sequenced to identify and compare CFH transcription start sites.

2.5. Promoter constructs

Using endogenous restriction enzyme sites or primers designed with the ‘Nhe I’ recognition sequence on the 5′ end of the desired product (Table 1), seven deletion constructs were created from the murine CFH (mCFH) promoter, with increasing numbers of nucleotides deleted from the 5′ untranslated region. In specified constructs, point mutations were made to three central nucleotides in identified transcription factor binding sites from transcription factor search engines such as TFsearch (http://www.cbrc.jp/research/db/TFSEARCH.html), Vista.com, and Generegulation.com. The site-directed mutations were made by creating DNA primers (Table 1) as directed in the Quikchange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). These mutants were then plasmid prepped for DNA extraction (Qiagen) and sequenced to verify the mutation.

2.6. Transient transfections and luciferase studies

The promoter deletion constructs created as described above were cloned into the pGL2 luciferase reporter vector (Promega, Madison, WI) and transfected into Ast 2.1 cells or primary astrocytes via the Ex-Gen transfection reagent (Fermentas, Thermofisher Scientific, Glen Burnie, MD) or Lipofectin reagent (Invitrogen), respectively. Each transfection was repeated at least three times. Briefly, the cells were plated at 6.5×104 cells for Ast 2.1 and 1×105 cells for primary astrocytes. Sixteen hours later, the cells were washed with PBS and treated with one μg of promoter construct DNA (for full-length constructs; smaller constructs were transfected in equimolar ratios relative to the full length construct) and 0.25 μg of the transfection control plasmid, pRL-null (Promega) to 3.3 μl of either Ex-Gen or Lipofectin. pRL-null was used to normalize transfection and cell lysis efficiency. The Lipofectin treated cells were transfected in Optimem serum-free media for six hours and then the media was replaced with DMEM (Gibco, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. In the case of the interferon-gamma studies, serum-free DMEM with 1% penicillin-streptomycin was utilized. The cells were cultured for 48 hours at 37°C and then harvested using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Kit (Promega), and the lysates were read via luminometer (Nichols Institute Diagnostics).

2.7 Phylogenetic footprinting

The CFH promoter was analyzed between six different species. The website ensembl (www.ensembl.org) was used to obtain the documented CFH sequences for each species, clustal w (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) was used to align the promoters of each species, and box shade 3.21 (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/BOX_form.html) was used to determine the sequence similarities and differences between nucleotides.

2.8. Cytokines

Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), as well as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1-beta (IL-lβ) and interleukin-6 (IL-6; all from Peprotech) were added to Ast 2.1 or primary astrocyte cultures for three hours (IFN-γ) or twenty-four hours prior to harvesting, maintained in the absence of serum. The cytokines were added in concentrations of 500 U/ml for IFN-γ and TNF-α, 200 U/ml for IL-6 and 1000 U/ml for IL-β.

2.9. Mobility Shift Assays

Nuclear extracts were prepared from Ast 2.1 cells utilizing the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent Kit (Pierce, ThermoFisher Scientific). The electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) oligonucleotide listed in Table 1 was labeled with biotin utilizing the Biotin 3′ End DNA Labeling Kit (Pierce, ThermoFisher Scientific). Unlabeled binding reactions were prepared using the Lightshift EMSA Optimization and Control Kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) in the absence or presence of 100-fold excess of unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides (Table 1). These unlabeled binding reactions were incubated at room temperature for ten minutes prior to labeled probe introduction. A 54 base pair oligonucleotide (Table 1; Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) that had been biotin-labeled (as described above) was incubated at ten μmoles with the nuclear extract for 20 minutes at room temperature. The reactions were then electrophoresed through a 6% DNA retardation gel (Invitrogen) in 0.5X TBE buffer (Ambion, Austin, TX) at 100 V at 4°C for 95 minutes and transferred onto Hybond N+ nylon membrane (Amersham/GE Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) for 80 minutes at 190 mA at 4°C in the X-cell Sure Lock (Invitrogen) tank blotting system. The membrane was then crosslinked twice via UV radiation (UV Stratalinker 2400, Stratagene, Agilent Technologies) and developed by the Chemiluminescent Nucleic Acid Detection Module (Pierce, ThermoFisher Scientific) and the ImageQuant LAS 4000 mini imager (GE Life Sciences). For supershift analysis, antibodies to c-Jun and c-Fos as well as nonspecific antibody CBF-α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) were introduced at a concentration of two μg/μl. These antibodies were incubated with the binding reactions for 30 minutes at room temperature concurrent with introduction of the labeled oligonucleotide (as listed above), before electrophoresis, transfer, crosslinking, and development as described above.

2.10 Statistical analysis

The student’s unpaired t-test (two-tailed distribution, homoscedastic, Microsoft Excel) was used to examine the probability that differences between transfection treatments were statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of CFH mRNA and protein in glial cells

In order to determine whether the glial cells of the CNS produce CFH mRNA, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes and microglia were separately analyzed by RT-PCR. These enriched cultures all expressed CFH at varying RT-PCR cycles, which suggest that CFH is produced locally by these cells (Figure 1a). To ensure that protein was also being produced by glial cells in the CNS, primary astrocytes as well as Ast 2.1 and Hepatocyte 3b cell lines (data not shown) were utilized to determine protein expression via western blotting. Primary liver tissue samples were included as a positive control for CFH staining, and staining at ~155 kDa by both liver and astrocyte samples indicate that CFH protein can also be produced locally in the CNS (Figure 1b). Additional protein species at lower weights were also identified; these bands likely represent other CFH family members, such as the CFH-related proteins and CFH-like 1, as these genes share sequence homology with CFH (Zipfel et al., 1999). Note that CFH-like 1 is likely expressed via the same promoter as is the CFH gene itself. These data suggest that CFH mRNA and protein are expressed in measurable levels in glial cell cultures.

Figure 1. RT-PCR analysis for murine CFH in cultures enriched for glial cells and protein analysis of CFH in astrocytes.

A. Messenger RNA was prepared from glial cell cultures and utilized in a one-step RT-PCR assay to measure CFH expression. All oligonucleotides spanned an exon to exclude genomic DNA amplification. B. Protein was prepared from murine liver samples (lane 1), primary astrocytes (lane 2), and murine astrocyte 2.1 cells (lane 3) (both astrocyte cultures were performed under serum free conditions) and analyzed for CFH expression via Western blot. Arrow shown corresponds to ~155 kDa.

3.2. Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE)

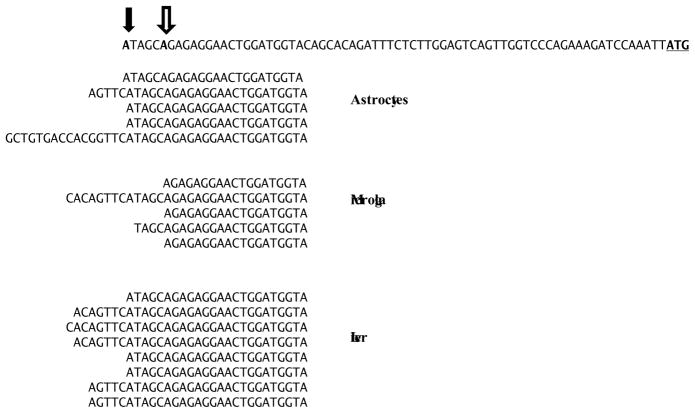

Since we determined CFH gene expression in glial cells, it was of interest to establish if the start site differed in CNS-specific cells from the already published liver start site. It was determined that between astrocytes, microglia and liver cells, a common CFH start site remained very similar amongst the three, all with initial adenosines. These start sites are located about 35 base pairs downstream from the previously published report (Figure 2). However, multiple start sites were cloned and sequenced which terminated further upstream from the most common start sites listed for astrocytes, microglia, and liver tissue. These data demonstrate that the cloned region represents the transcription start site.

Figure 2. RACE plot of the murine CFH promoter for astrocytes, microglia, and liver tissue.

Messenger RNA prepared from glial cell cultures was utilized in RACE reactions; the products are presented here. The likely transcriptional start site is represented with a filled arrow (astrocytes, liver) or an unfilled arrow (microglia).

3.3. Luciferase studies of the mCFH promoter

To study different regions of the mCFH promoter, the promoter was divided into deletion constructs of various lengths, created using endogenous restriction sites (Figure 3) or via primers (Table 1). These constructs were ligated into a luciferase reporter vector and transfected into the astrocyte cell line, Ast 2.1, or into primary astrocytes, and measured for luciferase activity. These studies indicate varying levels of luciferase activity in the promoter as compared to the non-truncated 2,076 base pair (bp) mCFH promoter used as a template for these constructs. The differing amounts of luciferase activity in the reporter vector (firefly luciferase) relative to the control vector (renilla luciferase) indicate that significant transcription factor enhancers and repressors exist in specific regions of the mCFH promoter (Figure 4). These data suggest that there are possible enhancers within the non-truncated promoter and the −1531 construct, and between the ends of the −416 and −250 bp constructs. Due to the significant increase in luciferase activity, repressors are likely acting between the −1531 and −841 and the −250 and −175 bp constructs.

Figure 3. Murine CFH promoter deletion construct map.

Roughly 2000 base pairs of the murine CFH promoter upstream from the start codon were utilized as a template, and different constructs were truncated at the 5′ end through restriction enzyme digest (as indicated) or through PCR (Nhe I). The position of each construct with respect to the transcription start site is indicated on the right-hand side. Not to scale.

Figure 4. Luciferase measurements of mCFH promoter constructs in primary astrocytes and astrocyte 2.1 cells.

The mCFH promoter constructs (Figure 3) were ligated into the pGL2 luciferase reporter vector, transfected into A. primary astrocytes or B. astrocyte 2.1 cells and assayed for luciferase activity. In all assays, luciferase activity was normalized to the activity of the control renilla luciferase plasmid. Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean for 3 replicates per treatment *p<0.03, #p<0.01.

Through database searches and phylogenetic alignments of different mammalian species (Figure 5), certain transcription factors, such as runt-related transcription factor 1/acute myeloid leukemia 1 (RunX1/AML-1), CCAAT enhancer binding protein beta (C/EBp-β), globin transcription factor 1 (GATA-1), and octamer-1 (Oct-1) were some of the attractive options as binding site candidates in the 241 bp region at −416 to −175 bp. Those sequences common to the most species suggest evolutionary significance and were further investigated utilizing mutagenesis and transcription factor binding studies.

Figure 5. Phylogenetic footprinting of CFH in six different species.

The −416 to −175 region of the mCFH promoter was analyzed among six different species utilizing the ensembl, clustalw and boxshade 3.21 websites. The nucleotides conserved in one or more species are boxed in black. Different transcription factor binding sites are underlined and labeled.

3.4. Cytokine studies

Due to the fact that inflammatory cytokines have a noted effect on CFH transcription in other tissues, the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β and IFN-γ were added to Ast 2.1 cell cultures or primary astrocytes prior to cell harvest for 24 hours, or 3 hours in the case of IFN-γ. It was determined that IFN-γ had effects on the transcriptional activity of the murine CFH promoter ranging from a 20% to 400% increase (Figure 6), while the rest of the cytokines assayed indicated no significant changes in promoter activity (data not shown). However, the two smallest constructs (−71 and −175 bp) were not affected by IFN-γ addition. This is likely due to the fact that the gamma-interferon activation sites are not located within these smallest constructs. These data indicate that the inflammatory cytokine IFN-γ can act alone on the CFH promoter to increase its transcriptional activity.

Figure 6. Cytokine effect on the murine CFH promoter in primary astrocytes and astrocyte 2.1 cells.

The mCFH promoter constructs (Figure 3) were ligated into pGL2 luciferase reporter vector and then transfected into A. primary astrocytes or B. astrocyte 2.1 cells. After treatment with IFN-γ for 3 hours, they were assayed for luciferase activity. In all assays, luciferase activity was normalized to the activity of the renilla luciferase reporter plasmid. Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean for 3 replicates per treatment. Data was normalized so untreated constructs were set to 100% luciferase activity.

3.5. Mutagenesis

Point mutations were made to six potential transcription factor binding sites found in the −416 to −175 bp region to determine their contribution to CFH promoter activity (Figure 7a). These mutated promoter constructs were then ligated into the pGL2 luciferase reporter vector and transfected into the Ast 2.1 cell line or primary astrocytes. The mutation at −295 bp was found to reduce activity in the mCFH promoter by ~90% (Figure 7b,c) and subsequently used to form the oligonucleotide for the EMSA assay (Table 1). The other five mutations did not change the luciferase activity in the CFH promoter (three not shown) and thus those corresponding transcription factor binding sites are not likely critical for CFH regulation in astrocytes.

Figure 7. Luciferase measurements of mCFH promoter mutant constructs in primary astrocytes and astrocyte 2.1 cells.

A. The sequence of the −416 bp region of the murine CFH promoter with specified mutations. The −416 bp wildtype and mutated constructs were ligated into the pGL2 luciferase reporter vector, transfected into B. primary astrocytes or C. astrocyte 2.1 cells and assayed for luciferase activity. In all assays, luciferase activity was normalized to the activity of the control renilla luciferase plasmid. Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean for 3 replicates per treatment.

3.6. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) and Supershift Assay

To better determine which transcription factor binding sites on the mCFH promoter are most likely to bind to cells of the CNS, more specifically, astrocytes, an EMSA was performed utilizing probes designed for the CFH promoter region of −416 to −175 (Table 1). The unlabeled competitor for the 54 bp probe successfully competed for binding with the biotin-labeled probe of the same sequence. However, an unlabeled competitor with the same three nucleotide mutation that was made in the site-directed mutagenesis study above (3.5) competed only partially for binding with the biotin-labeled oligonucleotide, suggesting that this is a transcription factor binding site of interest (Figure 8a). Further investigation with different truncations in the 54 bp oligonucleotide sequence suggest that the region of interest is located in the 3′ region of the nucleotide (data not shown), and that region was studied for potential transcription factor binding site candidates.

Figure 8. EMSA analysis and RT-PCR of transcription factors in murine CFH.

A. EMSA analysis of the murine CFH promoter utilizing Ast 2.1 cell nuclear protein extracts. A double-stranded probe encompassing the site significant in the mutagenesis studies was run alone (lane 1) or bound to the Ast 2.1 extract (lane 2), and unlabeled competitors (self, mutated) were additionally introduced in lanes 3 and 4, respectively. B. Supershift analysis of potential transcription factor binding site candidates. A double-stranded probe encompassing the site significant in the mutagenesis studies was run alone (lane 1) or bound to the Ast 2.1 extract (lane 2), and supershift antibodies c-Jun (lane 3), c-Fos (lane 4), CBF-α (lane 5), or unlabeled competitor (lane 6) was included.

The transcription factor binding site was then verified with the use of antibodies in a supershift assay (Figure 8b). An extra band is seen to be shifted up from the common oligonucleotide bands when the c-Jun kinase antibody is utilized. Additionally, when c-Fos is included in the binding reactions to the astrocyte nuclear extract, an extra band is seen that does not match the original oligonucleotide binding pattern. These data correspond to the activating protein 1 (AP-1) dimer that c-Jun and c-Fos form. Since c-Jun is known to interact with RunX1/AML-1 (D’Alonzo et al., 2002; Hess et al., 2001) the core binding factor-alpha (CBF-α antibody was also administered. CBF-α is a subunit of the RunX1/AML-1 transcription factor, and when it was included in the supershift analysis, no change occurred to the band arrangement relative to the oligonucleotide binding pattern. Additionally, another RUNX1 antibody and a C/EBp-β antibody were tested, as the mutated nucleotides in the original probe lie within the consensus sequences to these two transcription factors. No differences in the EMSA pattern were observed with these antibodies (data not shown). These data suggest that c-Jun and c-Fos bind to the 54 bp sequence of the mCFH promoter in astrocytes.

4. Discussion

In this report, we have demonstrated that CFH mRNA and protein are produced in CNS-specific cells, and in certain CNS cells, namely astrocytes, the CFH promoter is greatly influenced by the c-Jun and c-Fos transcription factors in a non-canonical binding site (Hope and Struhl, 1985). To our knowledge, this is the first report linking c-Jun and c-Fos to CFH. C-Jun and c-Fos are members of the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling pathway and form the heterodimeric transcription factor activating protein-1 (AP-1). AP-1 plays a significant role in cell proliferation and survival, with influence on apoptosis (Colotta et al., 1992; Karin et al., 1997; Kovary and Bravo, 1991). C-Jun and c-Fos are thought to be involved in apoptotic cell death in Alzheimer’s disease (Anderson et al., 1996; Marcus et al., 1998), which suggests that irregular expression of these transcription factors may impact the clearance of apoptotic neurons. Thus, a further understanding of how c-Jun, c-Fos and AP-1 interact with the CFH promoter in healthy and diseased individuals is extremely valuable to more precise and effective treatment options in pathology such as Alzheimer’s disease Additionally, a better understanding of cell cycle regulators interacting with complement and its regulators will be useful to understand how CFH is controlled in the CNS and the rest of the body.

The transcription start site of the CFH promoter had been documented decades ago utilizing the RNAse protection and S1 nuclease assays to determine the CFH start of transcription (Munoz-Canoves et al., 1989; Williams and Vik, 1997). Our analysis using the SMARTer RACE kit technology indicates an alternate start site in astrocytes and microglia, as well as in liver tissue. This method of investigation utilizes PCR to more easily and effectively document the upstream RNA sequences of the CFH promoter, unencumbered by faint autoradiographic signals, and unlimited by the size of the original probes. Many of the clones shared the same start site, lending support to a common start site among different cell types. The most common sequence was used to determine the start site; it is not clear whether the multiple clones determined in the CFH promoter of some of the cell types was due to inefficient extension of the reverse transcriptase to the end of the mRNA, or if there are several start sites, which is often the case in promoters lacking TATA boxes (Smale, 1997). It is common for a promoter without a canonical TATA box, as the murine CFH promoter is lacking, to have an initiator element that begins with the adenosine nucleotide and a cytosine base directly upstream of it, in the −1 position (Lodish, 2008). We found this to be true in our RACE studies.

Despite the fact that TNF-α, IL-6, IL-lβ and IFN-γ have all been implicated in CFH expression (Julen et al., 1992; Klein et al., 2005), our finding that IFN-γ is the one cytokine of the four to make an impact on CFH production in murine astrocytes is established in the literature for other cell types, such as hepatocytes, lung cells and human astroglioma cell lines (Gasque et al., 1995; Gasque et al., 1992; Williams and Vik, 1997). These data correspond to two IFN-γ activation sites (GAS), TTCNNGAA and TTNCNNNAA (Darnell et al., 1994) located at positions −237 to −228 and positions −194 to −185 within the mCFH promoter. These sites lie upstream of the two smallest mCFH promoter constructs labeled −175 and −71, which did not display any change to IFN-γ treatment.

This discrepancy in cytokine action on CFH may have to do with the cytokine receptors on astrocytes, although astrocytes do express TNFR1, IL-1R1 and IFN-γR (Hansson and Ronnback, 2004; Tada et al., 1994). Astrocytes do not respond to IL-6 well and not every astrocyte has the IL-6 receptor subunit gp130 (Van Wagoner and Benveniste, 1999), and this might be due to the fact that IL-6 needs to be administered with nerve growth factor to elicit a response (Jauneau et al., 2006). TNF-α has been thought to have no affect (Friese et al., 1999) or decrease CFH mRNA production that had been previously stimulated by IFN-γ (Williams and Vik, 1997). Additionally, in RPE cells, TNF-α and IL-6 were thought to downregulate CFH expression (Chen et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2009), indicating that TNF-α likely has a negative effect on CFH regulation but requires other cytokines. IL-1 has also been found to inhibit CFH secretion but not mRNA production (Brooimans et al., 1990). But perhaps these nonresponsive cytokines do not interact alone with astrocytes in vivo and a test utilizing multiple and potentially additional inflammatory cytokines together may yield a better result, as inflammatory situations never involve one cytokine in isolation.

The promoter studies utilizing the deletion constructs indicate specific regions of the CFH promoter that contain regulatory activity. While it has been documented that transcriptional enhancers and repressors can act on the transcriptional regulation of a promoter thousands of base pairs away from the transcriptional start site, we chose to focus our attention closer to the start site. Our findings that the region between −416 and −175 bps contains many important regulatory sites has been confirmed with the finding of major late transcription factor/upstream stimulatory factor binding site in liver cells (Kain et al., 1998). We saw similar results in both the primary astrocytes and the astrocyte cell line which lends strong support to this region being of significance to the mCFH promoter. Additionally, the comparison of multiple species in the phylogenetic footprint also suggests that the sequence of this region is highly conserved among species, suggesting evolutionary importance to the c-Jun and c-Fos transcription factor binding sites for CFH function.

There was also suggestion of a potential repressive element in the promoter of CFH in liver and kidney cells in a 300 bp region upstream and including the −416 to −175 bp region (Friese et al., 2003). This element was found to be active in kidney and liver cell lines but not fibroblasts, indicating the importance of cell specificity studies in gene promoters. The luciferase gene reporter analyses of the −416 to −175 bp region of the CFH promoter in astrocytes also suggest a repressor acts on the CFH promoter there (Figure 4), but the prior finding by Friese et al did not identify the transcription factor in question. Additonally, our studies indicated potential enhancers in the region between the −2,076 bp and −1531 bp constructs and possible repressors between the −1531 bp and −841 bp that we did not investigate. These regions may contain additional regulators important to CFH function that warrant future examination, as the deletion constructs suggested significant changes in luciferase reporter activity in both the primary and cell line studies.

Previously, there have been two specific sites in the CFH promoter where a mutation has been associated with disease. The site listed as C-257T has been associated with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) in nearly half of patients (Caprioli et al., 2003), and the site C-496T has been documented (Warwicker et al., 1997) and associated with Neisseria meningitidis (Haralambous et al., 2006). The existing documented cases of CFH and specifically the CFH promoter implicated in disease has begun a renewed interest in the study of CFH. The study of the transcriptional regulation of CFH is just one facet of investigation. CFH knockout mice studies as well as studies utilizing the transgenic c-Jun mouse c-JunAA and c-Fos deficient mouse in demyelinating disease models will be important steps in understanding the magnitude of CFH function in the CNS and the rest of the body. Cohort studies of CFH mutations involved in other diseases is another avenue of research to determine how important these mutations are to the human population. The regulation of the complement system remains a significant component of the immune system’s balance to maintain a healthy body, and the study of CFH is just one important protein to understand.

Highlights.

Complement Factor H mRNA and protein are expressed in glial cells.

Novel transcription start sites for factor H in glia and liver cells are reported.

Its promoter contains enhancers and repressors affected by inflammatory cytokines.

c-Jun and c-Fos can bind the factor H promoter in astrocytes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Scott Zamvil for providing the Astrocyte 2.1 cells.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- CFH

complement factor H

- MBL

Mannose-Binding Lectin

- kDa

kiloDalton

- CNS

central nervous system

- Ast 2.1

cell line astrocyte 2.1

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- RACE

Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends

- IFN-γ

Interferon-gamma

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- IL-1β

Interleukin-1-beta

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- mCFH

murine complement factor H

- bp

base pair

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- RunX1

runt-related transcription factor 1

- AML-1

Acute Myeloid Leukemia 1

- C/EBp-β

CCAAT enhancer binding protein-beta

- GATA-1

globin transcription factor 1

- Oct-1

Octamer-1

- CBF-α

Core Binding Factor-alpha

- MAP

mitogen-activation protein

- AP-1

activating protein-1

- GAS

IFN-Gamma Activation Site

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ajona D, Hsu YF, Corrales L, Montuenga LM, Pio R. Down-regulation of human complement factor H sensitizes non-small cell lung cancer cells to complement attack and reduces in vivo tumor growth. J Immunol. 2007;178:5991–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AJ, Su JH, Cotman CW. DNA damage and apoptosis in Alzheimer’s disease: colocalization with c-Jun immunoreactivity, relationship to brain area, and effect of postmortem delay. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1996;16:1710–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01710.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ault BH, Schmidt BZ, Fowler NL, Kashtan CE, Ahmed AE, Vogt BA, Colten HR. Human factor H deficiency. Mutations in framework cysteine residues and block in H protein secretion and intracellular catabolism. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997;272:25168–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery VM, Gordon DL. Characterization of factor H binding to human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Immunol. 1993;151:5545–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao L, Haas M, Quigg RJ. Complement factor H deficiency accelerates development of lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:285–95. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010060647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste EN, Kwon J, Chung WJ, Sampson J, Pandya K, Tang LP. Differential modulation of astrocyte cytokine gene expression by TGF-beta. Journal of immunology. 1994;153:5210–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste EN, Sparacio SM, Norris JG, Grenett HE, Fuller GM. Induction and regulation of interleukin-6 gene expression in rat astrocytes. Journal of neuroimmunology. 1990;30:201–12. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(90)90104-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bo L, Vedeler CA, Nyland HI, Trapp BD, Mork SJ. Subpial demyelination in the cerebral cortex of multiple sclerosis patients. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2003;62:723–32. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.7.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooimans RA, van der Ark AA, Buurman WA, van Es LA, Daha MR. Differential regulation of complement factor H and C3 production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells by IFN-gamma and IL-1. J Immunol. 1990;144:3835–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhe V, Loisel S, Pers JO, Le Ster K, Berthou C, Youinou P. Updating the physiology, exploration and disease relevance of complement factor H. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2010;23:397–404. doi: 10.1177/039463201002300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprioli J, Castelletti F, Bucchioni S, Bettinaglio P, Bresin E, Pianetti G, Gamba S, Brioschi S, Daina E, Remuzzi G, Noris M. Complement factor H mutations and gene polymorphisms in haemolytic uraemic syndrome: the C-257T, the A2089G and the G2881T polymorphisms are strongly associated with the disease. Human molecular genetics. 2003;12:3385–95. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charo IF, Ransohoff RM. The many roles of chemokines and chemokine receptors in inflammation. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;354:610–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Forrester JV, Xu H. Synthesis of complement factor H by retinal pigment epithelial cells is down-regulated by oxidized photoreceptor outer segments. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84:635–45. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colotta F, Polentarutti N, Sironi M, Mantovani A. Expression and involvement of c-fos and c-jun protooncogenes in programmed cell death induced by growth factor deprivation in lymphoid cell lines. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1992;267:18278–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu CS, Tani M, Ransohoff RM, Wysocka M, Hilliard B, Fujioka T, Murphy S, Tighe PJ, Das Sarma J, Trinchieri G, Rostami A. Astrocytes as antigen-presenting cells: expression of IL-12/IL-23. Journal of neurochemistry. 2005;95:331–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alonzo RC, Selvamurugan N, Karsenty G, Partridge NC. Physical interaction of the activator protein-1 factors c-Fos and c-Jun with Cbfa1 for collagenase-3 promoter activation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:816–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107082200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JE, Jr, Kerr IM, Stark GR. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science. 1994;264:1415–21. doi: 10.1126/science.8197455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierich MP, Erdei A, Gergely J, Myones BL, Schulz TF. T-cells and macrophages. Behring Institute; Mitteilungen: 1987. Complement-dependent triggering of B-cells; pp. 128–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiScipio RG, Daffern PJ, Schraufstatter IU, Sriramarao P. Human polymorphonuclear leukocytes adhere to complement factor H through an interaction that involves alphaMbeta2 (CD11b/CD18) J Immunol. 1998;160:4057–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierz W, Endler B, Reske K, Wekerle H, Fontana A. Astrocytes as antigen-presenting cells. I. Induction of Ia antigen expression on astrocytes by T cells via immune interferon and its effect on antigen presentation. J Immunol. 1985;134:3785–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana A, Fierz W, Wekerle H. Astrocytes present myelin basic protein to encephalitogenic T-cell lines. Nature. 1984;307:273–6. doi: 10.1038/307273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese MA, Hellwage J, Jokiranta TS, Meri S, Peter HH, Eibel H, Zipfel PF. FHL-1/reconectin and factor H: two human complement regulators which are encoded by the same gene are differently expressed and regulated. Molecular immunology. 1999;36:809–18. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(99)00101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese MA, Manuelian T, Junnikkala S, Hellwage J, Meri S, Peter HH, Gordon DL, Eibel H, Zipfel PF. Release of endogenous anti-inflammatory complement regulators FHL-1 and factor H protects synovial fibroblasts during rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2003;132:485–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02173.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasque P, Fontaine M, Morgan BP. Complement expression in human brain. Biosynthesis of terminal pathway components and regulators in human glial cells and cell lines. J Immunol. 1995;154:4726–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasque P, Ischenko A, Legoedec J, Mauger C, Schouft MT, Fontaine M. Expression of the complement classical pathway by human glioma in culture. A model for complement expression by nerve cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1993;268:25068–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasque P, Julen N, Ischenko AM, Picot C, Mauger C, Chauzy C, Ripoche J, Fontaine M. Expression of complement components of the alternative pathway by glioma cell lines. Journal of immunology. 1992;149:1381–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girvin AM, Gordon KB, Welsh CJ, Clipstone NA, Miller SD. Differential abilities of central nervous system resident endothelial cells and astrocytes to serve as inducible antigen-presenting cells. Blood. 2002;99:3692–701. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon DL, Avery VM, Adrian DL, Sadlon TA. Detection of complement protein mRNA in human astrocytes by the polymerase chain reaction. J Neurosci Methods. 1992;45:191–7. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(92)90076-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths MR, Neal JW, Fontaine M, Das T, Gasque P. Complement factor H, a marker of self protects against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2009;182:4368–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hageman GS, Anderson DH, Johnson LV, Hancox LS, Taiber AJ, Hardisty LI, Hageman JL, Stockman HA, Borchardt JD, Gehrs KM, Smith RJ, Silvestri G, Russell SR, Klaver CC, Barbazetto I, Chang S, Yannuzzi LA, Barile GR, Merriam JC, Smith RT, Olsh AK, Bergeron J, Zernant J, Merriam JE, Gold B, Dean M, Allikmets R. A common haplotype in the complement regulatory gene factor H (HF1/CFH) predisposes individuals to age-related macular degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:7227–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501536102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson E, Ronnback L. Glial-neuronal signaling and astroglial swelling in physiology and pathology. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2004;559:313–23. doi: 10.1007/0-387-23752-6_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haralambous E, Dolly SO, Hibberd ML, Litt DJ, Udalova IA, O’Dwyer C, Langford PR, Simon Kroll J, Levin M. Factor H, a regulator of complement activity, is a major determinant of meningococcal disease susceptibility in UK Caucasian patients. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38:764–71. doi: 10.1080/00365540600643203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harboe M, Ulvund G, Vien L, Fung M, Mollnes TE. The quantitative role of alternative pathway amplification in classical pathway induced terminal complement activation. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2004;138:439–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02627.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellendall RP, Ting JP. Differential regulation of cytokine-induced major histocompatibility complex class II expression and nitric oxide release in rat microglia and astrocytes by effectors of tyrosine kinase, protein kinase C, and cAMP. Journal of neuroimmunology. 1997;74:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(96)00202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess J, Porte D, Munz C, Angel P. AP-1 and Cbfa/runt physically interact and regulate parathyroid hormone-dependent MMP13 expression in osteoblasts through a new osteoblast-specific element 2/AP-1 composite element. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:20029–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey WF, Kimura H. Perivascular microglial cells of the CNS are bone marrow-derived and present antigen in vivo. Science. 1988;239:290–2. doi: 10.1126/science.3276004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope IA, Struhl K. GCN4 protein, synthesized in vitro, binds HIS3 regulatory sequences: implications for general control of amino acid biosynthetic genes in yeast. Cell. 1985;43:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura T, Ohtsuka H, Matsushita M, Tsuruta J, Okada H, Kambara T. A new biological activity of the complement factor H: identification of the precursor of the major macrophage-chemotactic factor in delayed hypersensitivity reaction sites of guinea pigs. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1992;185:505–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91653-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwama S, Sugimura Y, Suzuki H, Murase T, Ozaki N, Nagasaki H, Arima H, Murata Y, Sawada M, Oiso Y. Time-dependent changes in proinflammatory and neurotrophic responses of microglia and astrocytes in a rat model of osmotic demyelination syndrome. Glia. 2011;59:452–62. doi: 10.1002/glia.21114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauneau AC, Ischenko A, Chatagner A, Benard M, Chan P, Schouft MT, Patte C, Vaudry H, Fontaine M. Interleukin-1beta and anaphylatoxins exert a synergistic effect on NGF expression by astrocytes. J Neuroinflammation. 2006;3:8. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julen N, Davrinche C, Ozanne D, Lebreton JP, Fontaine M, Ripoche J, Daveau M. Differential modulation of complement factor H and C3 expression by TNF-alpha in the rat. In vitro and in vivo studies. Molecular immunology. 1992;29:983–8. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(92)90137-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kain SJ, Maldonado MJ, Vik DP. Analysis of the promoter region of the murine complement factor H gene. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1998;1397:241–6. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Liu Z, Zandi E. AP-1 function and regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:240–6. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YH, He S, Kase S, Kitamura M, Ryan SJ, Hinton DR. Regulated secretion of complement factor H by RPE and its role in RPE migration. Graefe’s archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology. Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1049-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RJ, Zeiss C, Chew EY, Tsai JY, Sackler RS, Haynes C, Henning AK, SanGiovanni JP, Mane SM, Mayne ST, Bracken MB, Ferris FL, Ott J, Barnstable C, Hoh J. Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:385–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1109557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovary K, Bravo R. The jun and fos protein families are both required for cell cycle progression in fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:4466–72. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.9.4466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodish HF. Molecular cell biology. W.H. Freeman; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchinetti C, Bruck W, Parisi J, Scheithauer B, Rodriguez M, Lassmann H. Heterogeneity of multiple sclerosis lesions: implications for the pathogenesis of demyelination. Annals of neurology. 2000;47:707–17. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200006)47:6<707::aid-ana3>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra R, Ward M, Sim RB, Bird MI. Identification of human complement Factor H as a ligand for L-selectin. The Biochemical journal. 1999;341(Pt 1):61–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus DL, Strafaci JA, Miller DC, Masia S, Thomas CG, Rosman J, Hussain S, Freedman ML. Quantitative neuronal c-fos and c-jun expression in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1998;19:393–400. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(98)00077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy KD, de Vellis J. Preparation of separate astroglial and oligodendroglial cell cultures from rat cerebral tissue. J Cell Biol. 1980;85:890–902. doi: 10.1083/jcb.85.3.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meri S, Pangburn MK. Discrimination between activators and nonactivators of the alternative pathway of complement: regulation via a sialic acid/polyanion binding site on factor H. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87:3982–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihlan M, Hebecker M, Dahse HM, Halbich S, Huber-Lang M, Dahse R, Zipfel PF, Jozsi M. Human complement factor H-related protein 4 binds and recruits native pentameric C-reactive protein to necrotic cells. Molecular immunology. 2009;46:335–44. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minta JO. Regulation of complement factor H synthesis in U-937 cells by phorbol myristate acetate, lipopolysaccharide, and IL-1. J Immunol. 1988;141:1630–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Canoves P, Tack BF, Vik DP. Analysis of complement factor H mRNA expression: dexamethasone and IFN-gamma increase the level of H in L cells. Biochemistry. 1989;28:9891–7. doi: 10.1021/bi00452a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabil K, Rihn B, Jaurand MC, Vignaud JM, Ripoche J, Martinet Y, Martinet N. Identification of human complement factor H as a chemotactic protein for monocytes. The Biochemical journal. 1997;326(Pt 2):377–83. doi: 10.1042/bj3260377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollert MW, David K, Bredehorst R, Vogel CW. Classical complement pathway activation on nucleated cells. Role of factor H in the control of deposited C3b. J Immunol. 1995;155:4955–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panickar KS, Norenberg MD. Astrocytes in cerebral ischemic injury: morphological and general considerations. Glia. 2005;50:287–98. doi: 10.1002/glia.20181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Caballero D, Gonzalez-Rubio C, Gallardo ME, Vera M, Lopez-Trascasa M, Rodriguez de Cordoba S, Sanchez-Corral P. Clustering of missense mutations in the C-terminal region of factor H in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:478–84. doi: 10.1086/318201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry VH, Hume DA, Gordon S. Immunohistochemical localization of macrophages and microglia in the adult and developing mouse brain. Neuroscience. 1985;15:313–26. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering MC, Cook HT, Warren J, Bygrave AE, Moss J, Walport MJ, Botto M. Uncontrolled C3 activation causes membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in mice deficient in complement factor H. Nature genetics. 2002;31:424–8. doi: 10.1038/ng912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schousboe A, Svenneby G, Hertz L. Uptake and metabolism of glutamate in astrocytes cultured from dissociated mouse brain hemispheres. Journal of neurochemistry. 1977;29:999–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb06503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim RB, Malhotra V, Ripoche J, Day AJ, Micklem KJ, Sim E. Complement receptors and related complement control proteins. Biochemical Society symposium. 1986;51:83–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smale ST. Transcription initiation from TATA-less promoters within eukaryotic protein-coding genes. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1997;1351:73–88. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(96)00206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. Neuroscience: Settling the great glia debate. Nature. 2010;468:160–2. doi: 10.1038/468160a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soos JM, Morrow J, Ashley TA, Szente BE, Bikoff EK, Zamvil SS. Astrocytes express elements of the class II endocytic pathway and process central nervous system autoantigen for presentation to encephalitogenic T cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:5959–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohmeyer R, Ramirez M, Cole GJ, Mueller K, Rogers J. Association of factor H of the alternative pathway of complement with agrin and complement receptor 3 in the Alzheimer’s disease brain. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2002;131:135–46. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00272-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada M, Diserens AC, Desbaillets I, de Tribolet N. Analysis of cytokine receptor messenger RNA expression in human glioblastoma cells and normal astrocytes by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:1063–73. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.80.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan LA, Yang AC, Kishore U, Sim RB. Interactions of complement proteins C1q and factor H with lipid A and Escherichia coli: further evidence that factor H regulates the classical complement pathway. Protein Cell. 2011;2:320–32. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1029-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagoner NJ, Benveniste EN. Interleukin-6 expression and regulation in astrocytes. Journal of neuroimmunology. 1999;100:124–39. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Hancock AM, Bradner J, Chung KA, Quinn JF, Peskind ER, Galasko D, Jankovic J, Zabetian CP, Kim HM, Leverenz JB, Montine TJ, Ginghina C, Edwards KL, Snapinn KW, Goldstein DS, Shi M, Zhang J. Complement 3 and factor h in human cerebrospinal fluid in Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and multiple-system atrophy. The American journal of pathology. 2011;178:1509–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warwicker P, Goodship TH, Goodship JA. Three new polymorphisms in the human complement factor H gene and promoter region. Immunogenetics. 1997;46:437–8. doi: 10.1007/s002510050300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler JM, Daha MR, Austen KF, Fearon DT. Control of the amplification convertase of complement by the plasma protein beta1H. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1976;73:3268–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.9.3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whaley K, Ruddy S. Modulation of C3b hemolytic activity by a plasma protein distinct from C3b inactivator. Science. 1976a;193:1011–3. doi: 10.1126/science.948757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whaley K, Ruddy S. Modulation of the alternative complement pathways by beta 1 H globulin. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1976b;144:1147–63. doi: 10.1084/jem.144.5.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SA, Vik DP. Characterization of the 5′ flanking region of the human complement factor H gene. Scandinavian journal of immunology. 1997;45:7–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1997.d01-364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Wu H, Khosravi M, Cui H, Qian X, Kelly JA, Kaufman KM, Langefeld CD, Williams AH, Comeau ME, Ziegler JT, Marion MC, Adler A, Glenn SB, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Pons-Estel BA, Harley JB, Bae SC, Bang SY, Cho SK, Jacob CO, Vyse TJ, Niewold TB, Gaffney PM, Moser KL, Kimberly RP, Edberg JC, Brown EE, Alarcon GS, Petri MA, Ramsey-Goldman R, Vila LM, Reveille JD, James JA, Gilkeson GS, Kamen DL, Freedman BI, Anaya JM, Merrill JT, Criswell LA, Scofield RH, Stevens AM, Guthridge JM, Chang DM, Song YW, Park JA, Lee EY, Boackle SA, Grossman JM, Hahn BH, Goodship TH, Cantor RM, Yu CY, Shen N, Tsao BP. Association of genetic variants in complement factor h and factor h-related genes with systemic lupus erythematosus susceptibility. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002079. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel PF, Jokiranta TS, Hellwage J, Koistinen V, Meri S. The factor H protein family. Immunopharmacology. 1999;42:53–60. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]