Abstract

Upon starvation, individual Dictyostelium discoideum cells enter a developmental program that leads to collective migration and the formation of a multicellular organism. The process is mediated by extracellular cAMP binding to the G protein-coupled cAMP receptor 1, which initiates a signaling cascade leading to the activation of adenylyl cyclase A (ACA), the synthesis and secretion of additional cAMP, and an autocrine and paracrine activation loop. The release of cAMP allows neighboring cells to polarize and migrate directionally and form characteristic chains of cells called streams. We now report that cAMP relay can be measured biochemically by assessing ACA, ERK2, and TORC2 activities at successive time points in development after stimulating cells with subsaturating concentrations of cAMP. We also find that the activation profiles of ACA, ERK2, and TORC2 change in the course of development, with later developed cells showing a loss of sensitivity to the relayed signal. We examined mutants in PKA activity that have been associated with precocious development and find that this loss in responsiveness occurs earlier in these mutants. Remarkably, we show that this loss in sensitivity correlates with a switch in migration patterns as cells transition from streams to aggregates. We propose that as cells proceed through development, the cAMP-induced desensitization and down-regulation of cAMP receptor 1 impacts the sensitivities of chemotactic signaling cascades leading to changes in migration patterns.

Keywords: Camp, Chemotaxis, Development, Dictyostelium, Signaling

Introduction

The directed migration of individual cells or chains or sheets of cells requires cells to transduce external cues into internal signals that regulate cytoskeletal reorganization and cell polarity. Signal transduction is important during development where the transition from single to collective cell migration is regulated by multiple external cues (1). Cell-cell communication, a process that can be manifested through the relay of external chemical signals (2, 3), is critical for a wide range of developmental processes including the survival of the social amoebae Dictyostelium discoideum.

Upon starvation, Dictyostelium cells enter a developmental program leading to the transition from cells operating individually to groups of cells operating as a population. Aggregation of starving cells is controlled by signaling centers that emit periodic pulses of 3′-5′-cAMP. This process is mediated by the binding of extracellular cAMP to the G protein-coupled receptor cAR1,3 which initiates a signaling cascade leading to, among other things, the activation of ACA (4). When ACA is first activated, rapid cAMP synthesis leads to a burst in internal cAMP levels. Although part of the synthesized cAMP remains inside cells to activate PKA and regulate gene expression, the majority of it is rapidly secreted (5–7). The secreted cAMP binds to cAR1 and, in an autocrine and paracrine amplification step, results in the production and secretion of more cAMP (2, 3). For a spatially extended cell population, the stimulated release of cAMP results in propagating spiral waves of cAMP secretion, allowing neighboring cells to polarize and migrate directionally and form characteristic chains of cells called streams as they move toward an aggregation center. The binding of cAMP also triggers the phosphorylation of the C-terminal tail of cAR1, which leads to a decrease in cAR1 affinity (8, 9). In addition, cAMP binding leads to adaptation processes where, after a short delay (30 s to 2 min), cells become desensitized to cAMP and do not signal to effectors (4). On the other hand, prolonged cAMP exposure (hours) results in sequestration and down-regulation of cAR1 (10–12).

The pathway leading to ACA activation is mediated through Gβγ subunits (13, 14) and requires input from both PI3K (15) and the target of rapamycin complex 2 (TORC2) (16–20). In addition, once synthesized, cAMP levels are regulated directly by the intracellular phosphodiesterase, RegA (21), and indirectly by the MAP kinase ERK2, which is thought to inhibit RegA (22). Intriguingly, PKA has also been reported to be part of this pathway by inhibiting ERK2 activity (22), although this remains controversial (23, 24).

Although the signaling pathways leading to ACA activation have been extensively studied, the timing of these events during development and how cAMP levels modulate the sensitivities of effectors during signal relay has not been investigated. In this study, we measured cAMP relay at successive time points during development. We used cells lacking either RegA (regA−) or the regulatory subunit of PKA (pkaR−) (25–27), which exhibit altered rates of development, and a combination of biochemical and functional assays to understand how the cAMP regulatory circuit controls signal relay. We show that as cells go through development, they lose sensitivity to relayed cAMP signals, which leads to changes in their migration patterns from streaming to aggregation. We envision that similar mechanisms are at play during embryonic development, where the transition from single cells to tissues is highly regulated.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Antibodies

Caffeine, ATP, cAMP, DTT, Sp-cAMPS (adenosine 3′-5′-monophosphorothioate Sp-isomer), and all other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise noted. [α-32P]ATP was purchased from MP Biomedical. cAR1 antibody (28) was a generous gift from Peter Devreotes (Johns Hopkins University). Antibodies recognizing specific phosphorylated sites were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-phospho-PKC (pan) antibody (190D10 rabbit monoclonal antibody, catalogue number 2060) was used to detect the phosphorylation of the activation loops of PKBR1. Anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) (Thr-202/Tyr-204) antibody (rabbit monoclonal antibody, catalogue number 4370) was used to detect the phosphorylation of ERK2.

Cell Culture and Differentiation

WT (AX3), regA−, and pkaR− cells were grown in shaking cultures to ∼5 × 106 cells/ml in HL5 medium (29). They were harvested by centrifugation, washed once in developmental buffer (5 mm Na2PO4, 5 mm NaH2PO4, pH 6.2, 2 mm MgS04, and 200 μm CaCl2) and finally resuspended in developmental buffer at 2 × 107 cells/ml. To allow development, the cells were orbitally shaken at 100 rpm for 3–7 h with repeated pulses of 75 nm cAMP every 6 min (30). The cells were then processed according to the assay performed.

Chemotaxis Assay

The EZ-Taxiscan chamber (Effector Cell Institute, Tokyo, Japan) was assembled as described by the manufacturer. The cells pulsed for the indicated time period were extensively washed in phosphate buffer (5 mm Na2PO4, 5 mm NaH2PO4, pH 6.2) and resuspended to 1 × 106 cells/ml. When cAMP is added to one side of each channel, a linear cAMP gradient forms and is maintained for >1 h. Cells introduced into the opposite wells were free to migrate within each channel. Images were recorded every 10 s for 30 min to assess chemotaxis and streaming. Cell migration analysis was conducted with MATLAB software. Briefly, bright field images were passed through a variance filter; the average image was subtracted to avoid tracking dead cells, clumps, or other stationary features. The subsequent images were binarized and segmented. Single cells were identified by their size and tracked from frame to frame by finding the maximum overlap with the next image. Cell tracks that persisted for more than 60 frames and displaced at least one cell length were used to compute chemotaxis index (CI) and speed for each tracked cells (31). The CI is defined as the ratio of a cell motion in the imposed gradient direction over the total cell motion.

Adenylyl Cyclase Assay

The cAR1-mediated activation of ACA was carried out as previously described (30). Briefly, developed cells were resuspended in phosphate magnesium buffer (5 mm Na2HPO4, 5 mm KH2PO4, pH 6.2, 2 mm MgSO4), stimulated with 1 nm or 10 μm cAMP, and filter lysed at the indicated time points into a Tris buffer containing [α-32P]ATP diluted with unlabeled ATP to a final concentration of ∼150 Ci/mol. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 1 min and stopped with SDS/ATP, and the [32P]cAMP was purified by sequential Dowex-AG 50W X-4 and alumina column chromatography. In the experiments with phosphodiesterase (PdsA), partially purified PdsA (32) was added 45 s after stimulation with cAMP.

Live Cell FRET Imaging and Analysis

FRET images were collected at different time points in development as previously described (33). Briefly, to measure FRET, three images were acquired for each set of measurements: (i) YFP fluorescence (514-nm excitation, 530-nm LP emission filter); (ii) CFP fluorescence (458-nm excitation, 475–505-nm BP emission filter); and (iii) FRET (458-nm excitation, 530-nm LP emission filter). To obtain a corrected FRET image, we acquired reference images from CFP-YFP expressing cells, which do not display FRET, and processed them using the pFRET software (Circusoft Instrumentation LLC, Hockessin, DE). The FRET efficiency images were used to obtain percentage FRET efficiency, and the results were averaged over many different single cells.

Immunoblotting and cAR1 Phosphorylation Assay

The cells were developed for the indicated time, treated with 5 mm caffeine for 30 min at 200 rpm on an orbital shaker, washed twice with ice-cold phosphate magnesium, resuspended to 2 × 107 cells/ml in phosphate magnesium, and kept on ice. The cells were stimulated with cAMP, lysed in SDS Laemmli buffer (34), and boiled for 5min. Supernatant samples were subjected to 4–20% Tris-Cl gradient SDS-PAGE analysis and transferred to Immobilon-P. The Immobilon-P was blotted with specific antibodies, and detection was performed by chemiluminescence using a donkey anti-mouse or anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-coupled antibody (Amersham Biosciences). For cAR1 phosphorylation analysis, caffeine-treated cells were stimulated with 1 nm or 10 μm cAMP for 15 min at room temperature, and cell lysates were electrophoresed on 7.5% Bis-Tris-Cl SDS-PAGE and then transferred to Immobilon-P as described above. The blots were probed with cAR1-specific antibody to look for mobility shifts in phosphorylated cAR1-specific signal.

RESULTS

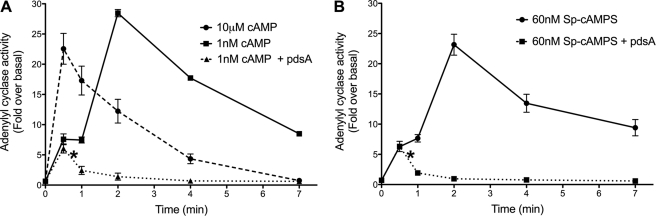

ACA Activity Measured following Subsaturating cAMP Stimulations Is a Biochemical Measurement of Signal Relay

ACA activity in Dictyostelium cells developed for 5 h has been mainly measured in response to saturating concentrations of cAMP (10 μm); the Kd of cAR1 for cAMP is reported to be ∼30 nm (35, 36). At this high 10 μm cAMP concentration, the adaptation of ACA activity is evident; the enzyme shows a fast rise in catalytic activity, peaking between 30 s and 1 min, followed by a return to basal activity within ∼3 min (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, when cells are stimulated with a subsaturating concentration of cAMP (1 nm), the activity pattern is different. We observe the expected small initial activation at 30 s to 1 min, followed by a near saturation response that peaks between 2 and 3 min and a delayed return to basal levels (Fig. 1A). We hypothesize that the later ACA activity is due to cAMP synthesized and secreted in response to the initial subsaturating stimulus. To test this, we added partially purified extracellular PdsA (32) to cells 45 s after the initial stimulus and measured ACA activity. We reasoned that the added PdsA would degrade the secreted cAMP and eliminate the second ACA activity peak. As predicted, we find that the later peak is completely abrogated in PdsA-treated cells (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, an identical result was obtained in cells stimulated with a subsaturating dose of the nonhydrolyzable cAMP analog, Sp-cAMPS, showing that the later peak is not due to a slow response to the initial subsaturating stimulus (Fig. 1B). We conclude that the sequential ACA activity measured under subsaturating conditions is a consequence of newly secreted cAMP and provides biochemical readout of signal relay.

FIGURE 1.

The ACA activity measured following subsaturating cAMP stimulations is a biochemical measurement of signal relay. A, ACA activity was measured after the addition of 1 nm or 10 μm cAMP in 5-h developed WT cells. Partially purified PdsA was added to cells 45 s after the initial cAMP stimulus (indicated by the asterisk). The absolute basal ACA activity (pmol/min/mg) value is 2.8 ± 0.6 S.D. (n = 3). B, ACA activity was measured after the addition of subsaturating concentration of the nonhydrolyzable cAMP analog Sp-cAMPS in WT cells. Partially purified PdsA was added to cells 45 s after the initial Sp-cAMPS stimulus (indicated by the asterisk). The absolute basal ACA activity (pmol/min/mg) value is 4.8 ± 0.2 S.D. (n = 3). The results represent the averages (± S.D.) of three independent experiments.

Subsaturating cAMP Stimulations Reveal Developmental Time-dependent Differences in ACA Activation

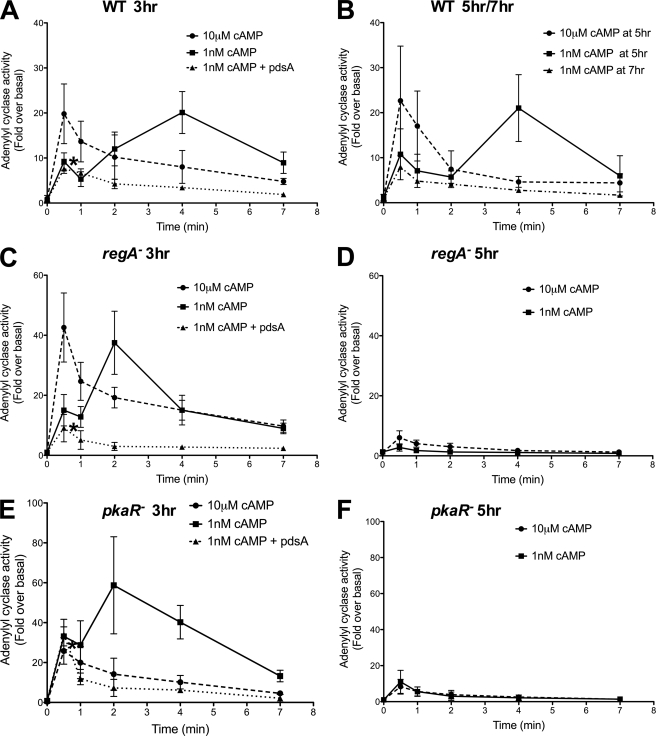

It has been previously reported that regA− cells develop rapidly with an early onset of wave activity (peaking at 3 h) compared with WT cells (peaking at 4.5 h) (37). Similarly, pkaR− cells have been reported to oscillate as early as 1–2 h after the initiation of starvation and then precociously form aggregates (24). Consistent with this data, we find that regA− and pkaR− cells show steady expression of the developmental marker cAR1 between 3 to 5 h of development (supplemental Fig. S1). To determine the consequence of these changes in cAR1 expression on the activity of ACA, we examined the ACA activity profile of 3 and 5 h developed WT, regA−, and pkaR− cells following saturating and subsaturating stimulation of cAMP. With 3-h developed cells, all three cell lines responded and adapted to a saturating 10 μm cAMP stimulus (Fig. 2, A, C, and E) and showed a sequential ACA activity to a subsaturating 1 nm cAMP stimulus (Fig. 2, A, C, and E). Moreover, in all three cell lines, the addition of PdsA 45 s following the exogenous 1 nm cAMP stimulus abrogated the secondary ACA response (Fig. 2, A, C, and E). With 5-h developed cells, although all three cell lines responded and adapted to a saturating 10 μm cAMP stimulus, the fold over basal stimulated ACA activity was substantially reduced in both regA− and pkaR− cells, compared with 3-h cells (Fig. 2, B, D, and F). Surprisingly, we also found that in response to the 1 nm cAMP stimulus, regA− and pkaR− cells did not exhibit the second ACA activity response observed in WT cells and only showed the initial, small ACA response (Fig. 2, B, D, and F). The second ACA activity peak associated with the secreted cAMP varied from 2 to 4 min in all cell lines and conditioned tested. Because regA− and pkaR− cells develop faster than WT cells, we measured ACA activity in WT cells developed for 7 h and found that, like the 5-h mutant cell lines, these more developed WT cells lose the sequential ACA activity profile (Fig. 2B). Together, these findings show that as cells progress through development, their ability to respond to relayed cAMP signals and subsequently stimulate ACA activity subsides.

FIGURE 2.

Subsaturating cAMP stimulations reveal developmental time-dependent differences in ACA activation. A, C, and E, ACA activity was measured in 3-h developed WT (A), regA− (C), and pkaR− (E) cells following 1 nm or 10 μm cAMP stimulations. Partially purified PdsA was added to cells 1 min after the initial stimulus (indicated by the asterisk) in each case as described in Fig. 1. The absolute basal ACA activity (pmol/min/mg) values are: 3.2 ± 0.8 S.D. (n = 3) for WT, 4.3 ± 0.9 S.D. (n = 3) for regA−, 4.9 ± 1.1 S.D. (n = 3) for pkaR−. B, D, and F, ACA activity was measured in 5-h developed WT (B), regA− (D), and pkaR− (F) cells following 1 nm or 10 μm cAMP stimulations. In addition, ACA activity was measured in 7-h developed WT cells (B) following a 10 μm cAMP stimulation. The absolute basal ACA activity (pmol/min/mg) values at 5 h are: 3.1 ± 0.6 S.D. (n = 3) for WT, 8.1 ± 1.15 S.D. (n = 3) for regA−, and 9.8 ± 0.9 S.D. (n = 3) for pkaR−, and the value at 7 h for WT is 9.1 ± 1.13 S.D. (n = 1). The results represent the average (± S.D.) of three independent experiments.

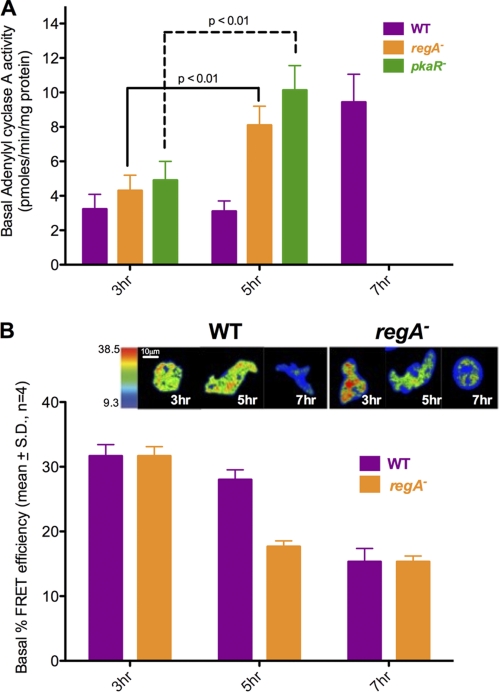

In Later Development, Cells Display High Basal ACA Activity and Intracellular cAMP Levels

We wondered whether the low level of ACA activation measured in cells developed for longer times could result from higher basal ACA activity and cAMP levels. We compared the basal ACA activity in WT, regA−, and pkaR− cells and found that 5-h regA− and pkaR− cells show significantly higher basal ACA activity levels compared with 3-h cells (Fig. 3A). This prompted us to measure the basal intracellular cAMP levels in WT and regA− cells developed for 5–7 or 3–5 h, respectively. For this purpose, we used a previously characterized cAMP FRET sensor, which harbors the PKA regulatory subunit cAMP-binding domain (B domain) flanked by eYFP and eCFP (33). At low cAMP levels, the probe remains in a closed state, and the FRET response is maximal. However, in the presence of cAMP, a conformational change occurs, and the FRET response is lost. WT and regA− cells stably expressing the cAMP probe were developed at different time points, and their basal FRET responses were measured. Fig. 3B depicts images of the basal FRET signal observed in both cell lines. As expected from our biochemical ACA measurements (Fig. 3A), the 5-h developed regA− cells show a robust decrease in FRET efficiency (corresponding to higher cAMP levels) compared with 3-h cells. Similarly, WT cells developed for 7 h exhibit high cAMP levels compared with 5-h cells (Fig. 3B). Together, these findings indicate that basal ACA activity is lowest at earlier stages of development, which leads to low intracellular cAMP levels and optimal ACA activation in response to chemoattractant addition. As cells go through development, this balance is altered, and high basal ACA activity gives rise to higher intracellular cAMP levels, which dampens the extent by which chemoattractants can further stimulate ACA by binding to cAR1.

FIGURE 3.

In later development, cells display high basal ACA activity and intracellular cAMP levels. A, the absolute basal ACA activity in pmol/min/mg was measured at indicated developmental time points as described in Fig. 1 in the absence of cAMP stimulation. The results represent the averages (± S.D.) of three independent experiments. B, basal FRET efficiency images represented in pseudo-color for 3–7-h developed WT and regA− cells. Percentage basal FRET efficiency was calculated from the FRET efficiency images, and results represent the averages ± S.D. from four independent experiments.

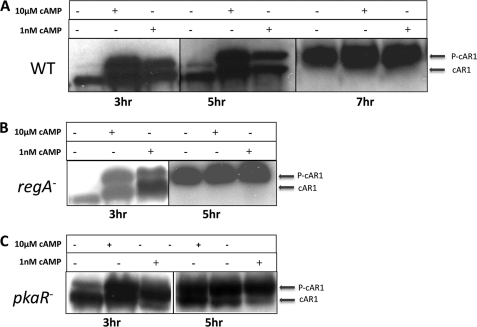

Basal cAR1 Phosphorylation Increases during Dictyostelium Development

It is well established that prolonged exposure of Dictyostelium cells to saturating doses of cAMP induces the phosphorylation of the C-terminal tail of cAR1, which is readily measured on Western blots by the presence of a slower migrating cAR1 band (9). Interestingly, it has been shown that upon prolonged high cAMP exposure, cAR1 phosphorylation is the first step in a sequential process that leads to inactivation and desensitization of cAR1 (12, 38). To explore how high basal ACA activity and higher basal cAMP levels in later developed cells might influence cAR1 activity, we measured the cAR1 phosphorylation (P-cAR1) status in 3- and 5-h developed cells. As depicted in Fig. 4, 3- and 5-h WT as well as 3-h regA− and pkaR− cells show a dramatic increase in P-cAR1 levels following both subsaturating and saturating cAMP stimulus. In these cells, caffeine pretreatment that inhibits ACA activation (39), resulted in a complete dephosphorylation of the receptor. In contrast, in 7-h WT cells (40) and 5-h regA− and pkaR− cells, a large proportion of cAR1 is found in its phosphorylated form, even before cAMP addition. These results show that as cAMP levels increase during development, the extent of P-cAR1 is enhanced to a point where P-cAR1 levels become insensitive to external increases in cAMP levels.

FIGURE 4.

Basal cAR1 phosphorylation increases during Dictyostelium development. cAR1 phosphorylation was measured in 3- or 5-h developed WT (A), regA− (B), and pkaR− (C) cells 15 min after 1 nm or 10 μm cAMP stimulations. In addition, cAR1 phosphorylation was measured in 7-h developed WT cells (A) 15 min after 1 nm or 10 μm cAMP stimulations. The data shown are representative of results from three independent experiments.

Subsaturating Doses of cAMP Induce a Relay Response for Both TORC2 and ERK2 Activity

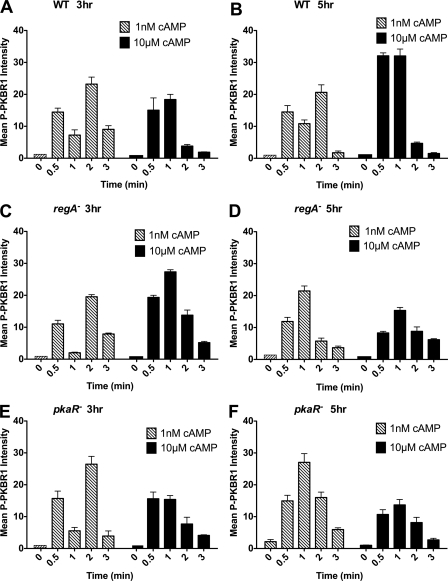

We have shown that cAMP relay can be observed biochemically by measuring ACA activity. We next explored whether signal relay can also be measured in other cAR1-mediated signaling pathways. Because TORC2 activation is necessary for ACA activity, we first examined the cAMP-mediated phosphorylation of PKBR1 at different developmental time points in WT and mutant cell lines. TORC2 mediates the phosphorylation of the hydrophobic motif of PKBR1 within its C-terminal regulatory domain (19, 41). In agreement with what we observed for ACA activation, we found that in 3- and 5-h developed WT cells, a saturating cAMP stimulus triggers a rapid phosphorylation of the hydrophobic motif of PKBR1, which peaks at 30–60 s and declines to basal levels by 2–3 min (Fig. 5, A and B; see supplemental Fig. S2 for a representative Western blot). In contrast, with a subsaturating cAMP input, both 3- and 5-h developed WT cells show an initial transient phosphorylation at 30 s followed by a secondary activation peak at 2 min, again very similar to the ACA activation profile under similar conditions (Fig. 5, A and B). Also in agreement with the ACA activity measurements, the sequential response is only observed under subsaturating conditions in 3-h regA− and pkaR− cells (Fig. 5, C–F). These findings establish that signal relay can be assessed through TORC2 activation in a developmental-dependent manner, much like ACA activation.

FIGURE 5.

Subsaturating stimulations induce a TORC2 relay response. A, C, and E, PKBR1 phosphorylation was used as a readout of TORC2 activity and was measured in 3-h developed WT (A), regA− (C), and pkaR− (E) cells following 1 nm or 10 μm cAMP stimulations. B, D, and F, PKBR1 phosphorylation was measured in 5-h developed WT (B), regA− (D), and pkaR− (F) cells following 1 nm or 10 μm cAMP stimulations. The results represent the averages (± S.D.) of three independent experiments. Also see supplemental Fig. S2 for a typical Western blot.

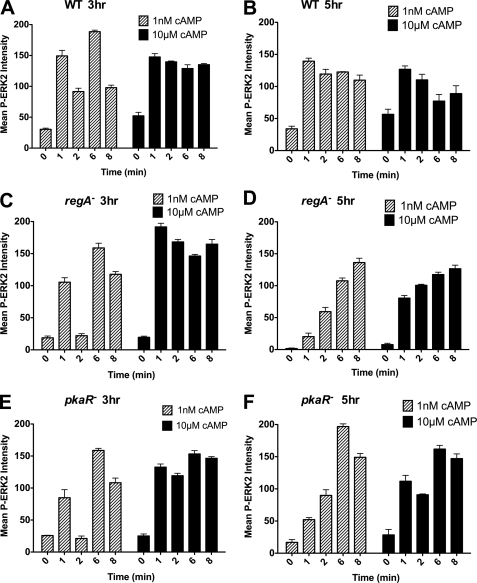

cAMP-bound cAR1 also leads to the phosphorylation of ERK2 in a G protein-independent manner, providing a readout for cAR1 occupancy (23, 42, 43). We find that a saturating cAMP stimulus gives rise to the phosphorylation of ERK2 in 3- and 5-h WT cells, peaking between 30 s and 1 min but persisting for at least 8 min (Fig. 6, A and B; see supplemental Fig. S3 for a representative Western blot), suggesting that cAR1 is persistently occupied under saturating conditions. However, in contrast to our ACA and TORC2 measurements, with a subsaturating cAMP stimulus, we observe a clear sequential ERK2 phosphorylation only in 3-h developed WT cells (Fig. 6A). Indeed, we found the ERK2 phosphorylation response to be very sensitive in WT cells, where the first peak of activity with 1 nm cAMP is comparable to the maximal response with a 10 μm stimulus. Similar observations were made with the mutants, although in the 5-h mutant cells, ERK2 phosphorylation steadily increased reaching a plateau at ∼6 min with a subsaturating cAMP stimulus (Fig. 6, C–F). We conclude that ERK2 activation represents a measure of signal relay in less developed cells.

FIGURE 6.

Subsaturating stimulations induce an ERK2 relay response. A, C, and E, ERK2 phosphorylation was measured in 3 h developed WT (A), regA− (C), and pkaR− (E) cells following 1 nm or 10 μm cAMP stimulations. B, D, and F, ERK2 phosphorylation was measured in 5-h developed WT (B), regA− (D), and pkaR− (F) cells following 1 nm or 10 μm cAMP stimulations. The results represent the averages (± S.D.) of three independent experiments. Also see supplemental Fig. S3 for a typical Western blot.

In Early Development, Signal Relay Directs Cells during Chemotaxis

The developmental differences in the ACA, PKBR1, and ERK2 activity profiles prompted us to assess the chemotactic and streaming ability of the WT, regA−, and pkaR− cells under various conditions. To assess the effect of prolonged development on directed migration, we examined the chemotactic behavior of 3-, 5-, and 7-h pulsed cells using the EZ-Taxiscan chemotaxis chamber, where cells are exposed to stable linear chemoattractant gradients ranging from 0 to 4 nm or 0 to 40 nm cAMP (44). We found that 3-h WT cells do not significantly migrate under all gradient conditions tested (Table 1 and supplemental Movie S1), with only a fraction of cells moving at an average speed of only 10 μm/min. We reason that after 3 h of starvation, the chemotactic machinery is not optimally expressed. However, 3-h regA− and pkaR− cells showed robust migration to both gradient conditions examined, moving with an average speed of 14–16 μm/min. To quantitatively compare the directedness of cell migration along the exogenous gradient, we computed the CI from cell tracks measured after 10 min of exposure to the gradient, when the cells had enough time to respond to the gradient and migrate accordingly. During this time, 3-h WT cells only weakly oriented with the external gradient (CI = ∼0.3), whereas the pkaR− and regA− cells migrated efficiently up both gradients conditions (CI = ∼0.7). As developmental time progressed, 5-h WT cells rapidly polarized and traversed the observation area efficiently (mean speed of ∼16 μm/min) and formed characteristic streams (supplemental Movie S1). The single cell directedness along the imposed gradient increased slightly with gradient strength (CI of 0.63 and 0.76, respectively; Table 1). Although 5-h regA− and pkaR− cells polarized and migrated with similar speeds as 3-h mutant and 5-h WT cells, the measured CI decreased by 20%. The mutant cells tended to migrate in clumps that coarsened with time into large aggregates (supplemental Movies S2 and S3). The reduction in CI correlated with cells moving toward the clumps and appears consistent with cells maintaining the ability to migrate directionally toward the gradient emanating from neighboring cells as opposed to the exogenous gradient. Similarly, 7-h WT cells initially showed robust migration (mean speed, 15 μm/min); however, in contrast to 5-h WT cells, these cells migrated toward each other to form aggregates resulting in a low CI of about 0.5 (supplemental Movie S1 and Table 1). The shift toward aggregation in cells that are developed for longer times clearly demonstrates that cells continue to secrete cAMP during later development, despite the lack of detection of the secondary response in the biochemical assays. Collectively, these results show that as cells develop, their ability to migrate and transition from single to group is altered in a way that promotes aggregation as opposed to streaming.

TABLE 1.

Chemotactic index and mean speeds of WT and mutants under different cAMP gradients during development

The results are expressed as the means and standard error of all local track speeds (determined from their displacement over three frames for >100 cell tracks). Individual cell tracks have marked speed ranging from 0 to twice the mean speed; the reported error is not indicative of the fluctuations in a single cell speed over time. However, the average speed over all local cell trajectories for a given condition is reproducible from experiment to experiment within the standard error reported. CI, chemotactic index.

| WT |

pkaR− |

regA− |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–4 nm cAMP | 0–40 nm cAMP | 0–4 nm cAMP | 0–40 nm cAMP | 0–4 nm cAMP | 0–40 nm cAMP | |

| 3 h | ||||||

| CI | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.73 ± 0.03 | 0.75 ± 0.03 | 0.75 ± 0.03 | 0.66 ± 0.03 |

| Mean speed (μm/min) | 10.0 ± 0.1 | 11.0 ± 0.1 | 17.2 ± 0.2 | 16.9 ± 0.1 | 15.6 ± 0.2 | 14.3 ± 0.2 |

| 5 h | ||||||

| CI | 0.63 ± 0.04 | 0.76 ± 0.03 | 0.60 ± 0.06 | 0.65 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.03 | 0.54 ± 0.04 |

| Mean speed (μm/min) | 15.7 ± 0.2 | 17.7 ± 0.2 | 17.3 ± 0.2 | 15.4 ± 0.2 | 17.3 ± 0.2 | 15.2 ± 0.2 |

| 7 h | ||||||

| CI | 0.51 ± 0.12 | 0.42 ± 0.08 | ||||

| Mean speed (μm/min) | 15.3 ± 0.1 | 13.2 ± 0.2 | ||||

DISCUSSION

Dictyostelium cells have evolved to use a sophisticated signal relay cascade that allows the generation of coordinated intercellular signals through pulses of cAMP, which are coupled to chemotaxis (4). However, the dynamics of signaling pathways during signal relay in the early stages of Dictyostelium aggregation has been relatively unexplored. In this report, we used key biochemical pathways as a direct read out of cell sensitivity to the signal relay loop. By probing a cell's response to a spatially uniform subsaturating cAMP stimulus, we show that signal relay can be monitored at various stages of development by studying effectors downstream to cAR1 such as ACA, TORC2, and ERK2. Our findings show a developmental time sensitivity of these effector pathways and go beyond previous studies, where cAMP production was most often used as readout of exogenous cAMP stimuli. First, we show that the short term cessation of ACA activity is normal in 3-, 5-, and 7-h WT cells as well as in 3- and 5-h mutant cell lines. These findings establish that ACA adaptation is not mediated through changes in intracellular cAMP levels or PKA activity, as previously suggested (21, 22, 45). Second, following subsaturating stimulations, we observed a strong burst of secondary ACA activity that corresponds to the relayed cAMP signal. This relayed response is present in WT and mutant cells and disappears as the cells age during development. Third, we measured higher basal ACA activity and intracellular cAMP levels in 5-h mutant cell lines as well as in 7-h WT cells. Previous studies on regA− cells also revealed higher levels of cAMP, compared with WT cells; however, these studies did not detect the sequential response we observed in our study (22). Similarly, pkaR− cells have been reported to exhibit developmental phenotypes suggestive of high cAMP levels, which include early onset of oscillations, aberrant spiral wave formation, and small aggregate size (24). Finally, we find that signal relay can be directly measured by monitoring TORC2 and ERK2 activities during development. However, unlike ACA activity, we did not detect higher basal TORC2 and ERK2 activities in later developed cells, leaving open the mechanism by which ACA activity is up-regulated as development proceeds.

We found it essential to assess cAMP-receptor dependent signaling pathways in both WT and mutants at multiple time points in the developmental cycle. Indeed, a comparison of 5-h developed cells may suggest a role for RegA and PKA in directly regulating ACA activity. However, an examination of other signaling pathways throughout the developmental cycle identified a secondary effect of internal cAMP levels on ACA activity through the PKA-dependent modulation of cAR1 sensitivity under persistent cAMP stimulus. In mammalian cells, G protein-coupled receptor phosphorylation is linked to receptor desensitization, a process by which the activity of effectors subsides in the presence of stimulus. In most cases, the desensitization process involves receptor uncoupling from their cognate G proteins and down-regulation (46). Similarly, in Dictyostelium, it has been shown that the cAMP-induced desensitization of cAR1 proceeds in at least two steps. The first step is rapid (min), is reversible, occurs at low cAMP concentrations, and involves a decrease in receptor affinity without down-regulation (8, 38, 47). The second step is essentially irreversible, requires prolonged cAMP exposure (hours), and leads to the down-regulation of receptors, which become either sequestered within the plasma membrane or internalized (10–12). Because this irreversible process of down-regulation has been shown to be a PKA-mediated event (12), we envisioned that the high cAMP levels and hence high PKA activity in regA− and pkaR− cells would drive cAR1 down-regulation to occur at a much earlier developmental stage compared with WT cells, leading to the observed decrease in cAR1-dependent signal transduction responses. We indeed measured a shift to higher P-cAR1 levels in earlier developmental time points in both regA− and pkaR− cells compared with WT cells. Most importantly, we found that higher P-cAR1 levels (in 5-h mutant cells or 7-h WT cells) correlate with the absence of secondary ACA/TORC2/ERK2 activity peaks, higher basal ACA activity, high cAMP levels, and weaker chemotactic abilities of cells toward an exogenous gradient.

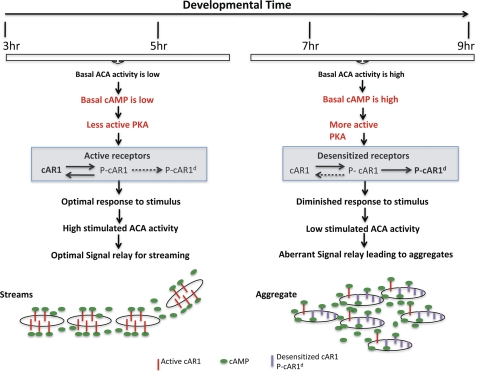

Together, these observations allow us to propose a model that explains how signal transduction cascades are regulated during development (Fig. 7). Optimal signal relay, observed in 3–5-h WT cells, occurs when basal activity of ACA is low, leading to low basal internal cAMP and PKA activity levels. Upon stimulation, ACA is activated and produces high cAMP levels compared with basal. Because of low basal PKA activity, the majority of cAR1 are sensitive and rapidly phosphorylated in a reversible manner, returning to their basal dephosphorylated state as extracellular PDE degrades the secreted pool of cAMP (48, 49). In a spatially extended system observed during chemotaxis, this optimal signaling induces neighboring cells to sense each other and align head-to-tail to form streams. As the cells age, the time-integrated exposure to cAMP results in higher average PKA activity, which leads to more down-regulated receptors. Under these conditions, the basal ACA activity and basal internal cAMP levels are higher. Upon stimulation, binding to the smaller pool of active receptors slightly increases ACA activity producing a relative smaller cAMP increase. We have previously proposed that cAMP secretion is a PKA-regulated event that occurs through the polarized release of exosomes expressing ACA (33, 50). We envision that in later development, high PKA activity leads to aberrant secretion, which leads to the formation of disorganized stream, poor chemotaxis to exogenous signals, and the formation of small aggregates. It therefore appears that changes in cell sensitivity to the relayed cAMP signal represent an important developmental switch to instruct cells to convert their migration pattern from the formation of head-to-tail streams to the aggregation in a tight mound, which is the entry event to later development leading to the formation of a multicellular structure.

FIGURE 7.

Schematic depicting the signal transduction events that lead to desensitized responses during the early development of Dictyostelium. See text for details.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The regA− and pkaR− cells were obtained through the Dicty Stock Center via dictybase.org. We thank the Parent laboratory members, as well as Wolfgang Losert for excellent discussions and suggestions and for valuable input on the manuscript. A special thanks goes to Drs. Philippe Afonso, Paul Kriebel, Michael Weiger, and Colin McCann for reading the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the National Institutes of Health NCI Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Movies S1–S3 and Figs. S1–S3.

- cAR1

- cAMP receptor 1

- ACA

- adenylyl cyclase A

- TORC2

- target of rapamycin complex 2

- CI

- chemotaxis index

- PdsA

- phosphodiesterase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Weijer C. J. (2009) J. Cell Sci. 122, 3215–3223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McMains V. C., Liao X. H., Kimmel A. R. (2008) Ageing Res. Rev. 7, 234–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Garcia G. L., Parent C. A. (2008) J. Microsc. 231, 529–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Swaney K. F., Huang C. H., Devreotes P. N. (2010) Annu. Rev. Biophys. 39, 265–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dinauer M. C., MacKay S. A., Devreotes P. N. (1980) J. Cell Biol. 86, 537–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dinauer M. C., Steck T. L., Devreotes P. N. (1980) J. Cell Biol. 86, 545–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Devreotes P. N., Steck T. L. (1979) J. Cell Biol. 80, 300–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xiao Z., Yao Y., Long Y., Devreotes P. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 1440–1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caterina M. J., Devreotes P. N., Borleis J., Hereld D. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 8667–8672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang M., Van Haastert P. J., Devreotes P. N., Schaap P. (1988) Dev. Biol. 128, 72–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Van Haastert P. J. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 7700–7704 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Haastert P. J. (1994) Biochem. J. 303, 539–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang N., Long Y., Devreotes P. N. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 3204–3213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wu L., Valkema R., Van Haastert P. J., Devreotes P. N. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 129, 1667–1675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Comer F. I., Parent C. A. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 357–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen M. Y., Long Y., Devreotes P. N. (1997) Genes Dev. 11, 3218–3231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee S., Parent C. A., Insall R., Firtel R. A. (1999) Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 2829–2845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee S., Comer F. I., Sasaki A., McLeod I. X., Duong Y., Okumura K., Yates J. R., 3rd, Parent C. A., Firtel R. A. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 4572–4583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cai H., Das S., Kamimura Y., Long Y., Parent C. A., Devreotes P. N. (2010) J. Cell Biol. 190, 233–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Charest P. G., Shen Z., Lakoduk A., Sasaki A. T., Briggs S. P., Firtel R. A. (2010) Dev Cell 18, 737–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laub M. T., Loomis W. F. (1998) Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 3521–3532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maeda M., Lu S., Shaulsky G., Miyazaki Y., Kuwayama H., Tanaka Y., Kuspa A., Loomis W. F. (2004) Science 304, 875–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brzostowski J. A., Kimmel A. R. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 4220–4227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sawai S., Thomason P. A., Cox E. C. (2005) Nature 433, 323–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shaulsky G., Fuller D., Loomis W. F. (1998) Development 125, 691–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang H., Heid P. J., Wessels D., Daniels K. J., Pham T., Loomis W. F., Soll D. R. (2003) Eukaryot. Cell 2, 62–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aubry L., Firtel R. (1999) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 15, 469–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hereld D., Vaughan R., Kim J. Y., Borleis J., Devreotes P. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 7036–7044 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sussman M. (1987) Methods Cell Biol. 28, 9–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Parent C. A., Devreotes P. N. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 22693–22696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McCann C. P., Kriebel P. W., Parent C. A., Losert W. (2010) J. Cell Sci. 123, 1724–1731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Garcia G. L., Rericha E. C., Heger C. D., Goldsmith P. K., Parent C. A. (2009) Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 3295–3304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bagorda A., Das S., Rericha E. C., Chen D., Davidson J., Parent C. A. (2009) J. Cell Sci. 122, 3907–3914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Laemmli U. K. (1970) Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Johnson R. L., Vaughan R. A., Caterina M. J., Van Haastert P. J., Devreotes P. N. (1991) Biochemistry 30, 6982–6986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Johnson R. L., Van Haastert P. J., Kimmel A. R., Saxe C. L., 3rd, Jastorff B., Devreotes P. N. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 4600–4607 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thomason P. A., Traynor D., Stock J. B., Kay R. R. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 27379–27384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Caterina M. J., Hereld D., Devreotes P. N. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 4418–4423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brenner M., Thoms S. D. (1984) Dev. Biol. 101, 136–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Johnson R. L., Saxe C. L., 3rd, Gollop R., Kimmel A. R., Devreotes P. N. (1993) Genes Dev. 7, 273–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kamimura Y., Xiong Y., Iglesias P. A., Hoeller O., Bolourani P., Devreotes P. N. (2008) Curr. Biol. 18, 1034–1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brzostowski J. A., Kimmel A. R. (2001) Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 291–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Maeda M., Aubry L., Insall R., Gaskins C., Devreotes P. N., Firtel R. A. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 3351–3354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nitta N., Tsuchiya T., Yamauchi A., Tamatani T., Kanegasaki S. (2007) J. Immunol. Methods 320, 155–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mann S. K., Brown J. M., Briscoe C., Parent C., Pitt G., Devreotes P. N., Firtel R. A. (1997) Dev. Biol. 183, 208–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Luttrell L. M. (2006) Methods Mol. Biol. 332, 3–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Serge A., de Keijzer S., Van Hemert F., Hickman M. R., Hereld D., Spaink H. P., Schmidt T., Snaar-Jagalska B. E. (2011) Integr. Biol. 3, 675–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lacombe M. L., Podgorski G. J., Franke J., Kessin R. H. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261, 16811–16817 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bader S., Kortholt A., Van Haastert P. J. (2007) Biochem. J. 402, 153–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kriebel P. W., Barr V. A., Rericha E. C., Zhang G., Parent C. A. (2008) J. Cell Biol. 183, 949–961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.