Abstract

This work compares the photoinduced unimolecular electron transfer rate constants for two different solute molecules (D-SSS-A and D-SRR-A) in water and DMSO solvents. The D-SSS-A solute has a cleft between the electron donor and electron acceptor unit, which is able to contain a water molecule but is too small for DMSO. The rate constant for D-SSS-A in water is significantly higher than that for D-SRR-A, which lacks a cleft, and significantly higher for either solute in DMSO. The enhancement of the rate constant is explained by an electron tunneling pathway that involves water molecule(s).

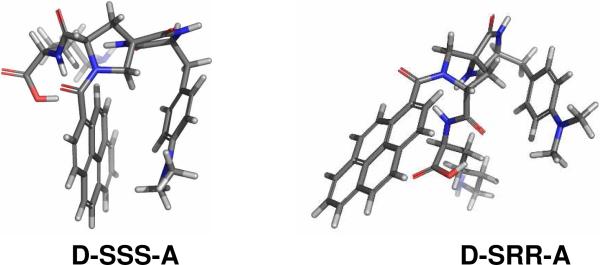

Water molecules influence electron transport in biomolecules and play a key role in biologically vital processes in living cells.1-3 The importance of water in determining the activation energy for electron transfer (ET) reactions is well appreciated. Recent theoretical work shows that placement of a few water molecules between electron donor and acceptor moieties can change the electronic tunneling probability between them.4-6 Although some experimental studies have probed electron tunneling in frozen water7,8 the experimental study of electron tunneling through water molecules under ambient conditions is lacking. This work investigates the role of water molecules by studying the photoinduced electron transfer rate in two Donor-Bridge-Acceptor (DBA) bis-amino acid oligomers that contain a pyrene carboxamide group as an acceptor unit and dimethylaniline (DMA) as a donor unit in water and DMSO. The DBA molecules differ by their bridge stereochemistry (Figure 1). One amide rotamer of the D-SSS-A bridge forms a cleft between the donor and acceptor whereas the D-SRR-A bridge geometry does not form any well defined cleft. Here SSS and SRR indicate the stereochemistry at the α-carbon of the dimethylaminophenylalanine residue and the 2 and 4 positions of the pyrrolidine ring respectively. This difference in geometry also provides two different “line-of-sight” donor to acceptor distances 4.6 Å and 9.7 Å, respectively, but the same number and types of covalent bonds through the bridge.9

Figure 1.

Structures of bis-amino acid DBA molecules with different bridge stereochemistry are shown.

Work in organic solvents shows that photoinduced electron transfer in DBA supermolecules with a cleft between the donor and acceptor moieties can proceed by electron tunneling through solvent molecules residing in the cleft.10-13 The ET rates of the two compounds in Figure 1 were studied in two different solvents, water and dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO), as a function of temperature to probe the effect of water molecules on the ET kinetics and compare to DMSO as a ‘control’ solvent. Synthesis of the bis-amino acid oligomers with different length has been reported elsewhere14 (see Supporting Information).

One-dimensional 1H NMR experiments indicate that D-SSS-A in both D2O and DMSO and D-SRR-A in D2O at 330 - 333 K each occupy two rotameric conformations with essentially identical average population ratios (see Table 1). In both solvents, the more populated conformation of D-SSS-A is the cleft conformation shown in Fig. 1, in which the pyrene is rotated close to the dimethylaniline hydrogens resulting in upfield chemical shifts of the DMA peaks. These data indicate that the conformational preferences of the DBA molecules are similar in DMSO and H2O.

Table 1.

Electron transfer parameters (|V|, ΔrG, λS) and rotamer populations for D-SSS-A and D-SRR-A

| DBA/solvent | |V|(cm-1)b | ΔrG (eV)b | λS (eV)26 | Pop.a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-SSS-A/H2O | 35 ± 6 | -0.66 ± 0.02 | 1.42 | 63:37 |

| D-SRR-A/H2O | 12 ± 2 | -0.54 ± 0.01 | 1.12 | 63:37 |

| D-SSS-A/DMSO | 11 ± 2 | -0.55 ± 0.01 | 1.12 | 65:35 |

| D-SRR-A/DMSO | 13 ± 2 | -0.36 ± 0.01 | 0.91 | n/d |

Population ratio of two amide rotamers at 330 – 333K

Error shows effect of a ±0.1 eV variation in λS

The molecules in Figure 1 have the same donor and acceptor unit, and ET occurs when the pyrene carboxamide moiety is electronically excited by 330 nm light. This donor and acceptor pair has been used for intramolecular ET studies in different organic solvents in the past.15, The fluorescence decay law is well described by a double exponential and the two time components are ascribed to the two rotamers; the longer decay time is the less populated conformer (donor and acceptor far apart) and the short decay time is the more populated conformer; those shown in Fig. 1. The short lifetime component was used to determine the electron transfer rate constant, kET, for the cleft rotamer (details in Supplemental Information).16 The pH of the water solution was kept ~7 to avoid any protonation of the amine group of the dimethylaniline donor unit.17

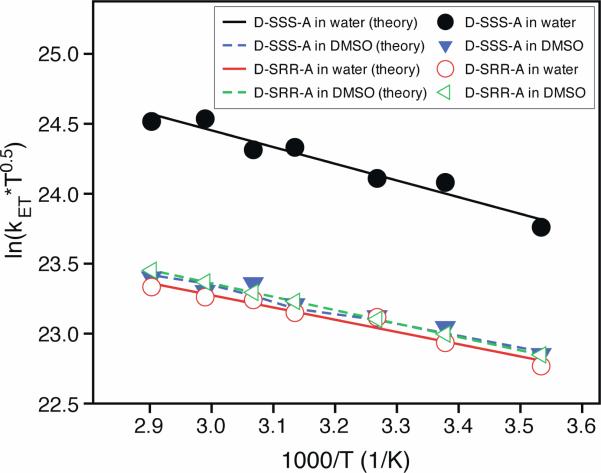

Figure 2 shows how kET for D-SRR-A and D-SSS-A depend on temperature, in water and DMSO. The activation energies are very similar (ranging from 1.5 kJ/mol to 2.1 kJ/mol). For D-SSS-A kET is about three times larger in water than in DMSO and is three times larger than the kET measured for D-SRR-A.

Figure 2.

These plots show the temperature dependence of the kET for D-SSS-A in water (filled circle) and DMSO (filled triangle) and for D-SRR-A in water (open circle) and DMSO (open triangle). The lines represent fits by the semiclassical ET model.

The semiclassical electron transfer theory expresses the electron transfer rate constant as the product of the square of the electronic coupling, |V|2, and the Franck-Condon weighted density of states (FCWDS). Using the semiclassical Marcus equation18,19 to calculate the rate constant requires knowledge of the electronic coupling (|V|), the Gibbs free energy (ΔrG), the solvent reorganization energy (λS), and the internal reorganization energy parameters.20,21 The internal reorganization energy parameters (λV and ν) are primarily determined by the molecular characteristics of the donor and acceptor, and the values for pyrene and dimethylaniline were taken from a previous study15 to be λV = 0.19 eV and ν = 1400 cm-1. The lines in Fig 2 show fits of the experimental rate data by this model with ΔrG and |V| as adjustable parameters. The solvent reorganization energy λS was calculated using a continuum model.22,23 The values for the reorganization energies were kept constant throughout the analysis; i.e., no temperature dependence was included.

The ΔrG and |V| obtained from the fit are reported in Table 1. The ΔrG is found to be more negative for compound D-SSS-A than D-SRR-A in water and DMSO. The difference in Gibbs energy for D-SSS-A and D-SRR-A likely reflects the difference in Coulomb stabilization of the charge separated state, however an accurate assessment will require modeling that includes the electrostatic properties and polarizability of the solvent molecules, as well as the solute.24,25 The |V| obtained from the fits are very similar for the two solutes in DMSO, however the |V| obtained for D-SSS-A in water is significantly higher than that found for D-SRR-A in water. In all cases the coupling values are modest and consistent with a nonadiabatic coupling mechanism.

The enhancement in |V| for D-SSS-A in water, over that for D-SRR-A, may reflect a change in the tunneling pathway, from a bridge mediated process to a solvent mediated process. The similarity of the electronic coupling for D-SRR-A in DMSO and H2O suggests that the coupling is determined by a bridge mediated superexchange interaction, hence it is solvent independent. In contrast, the cleft molecule D-SSS-A shows a solvent dependence (a larger |V| for H2O than for DMSO). For a donor to acceptor distance of 4.5 Å and accounting for the π-cloud extents, the space available in the cleft is about 1.2 Å.27 This value is comparable to the van der Waals radius of H2O (ca. 1.4 Å) but significantly smaller than that of a DMSO molecule (ca. 2.5 Å).28 Hence we postulate that for DMSO the electron tunneling must occur through the ‘empty’ cleft or by way of the bridge, whereas in water an H2O molecule can reside in the cleft and mediate the electron tunneling or bind alongside the cleft to act as a short bridge/tunneling pathway.

An alternative mechanism to explain the observations involves proton motion that is coupled to the ET,29-31 i.e., a proton coupled electron transfer (PCET). To evaluate this possibility, kET was determined for the DBA compounds in deuterium oxide (D2O). A significant normal kinetic isotope effect was observed (kET,H2O/kET, D2O = 1.49 for D-SSS-A and kET, H2O/kET, D2O = 1.17 for D-SRR-A at 295K). Both molecules display an isotope effect, however it is more pronounced in D-SSS-A. The detailed origin of the enhancement of the rate for D-SSS-A in water requires further investigation.

Whichever mechanism operates, it seems clear that electron transfer for D-SSS-A involves one or more H2O molecules. The higher kET for D-SSS-A/H2O, as compared to the similar rates for D-SRR-A/ H2O and both solutes in DMSO, suggests that water molecules play a special role for D-SSS-A/H2O. The observation of an isotope effect that is stronger for D-SSS-A than for the D-SRR-A system suggests that hydrogen bonded network(s) protons play a role. In terms of the semiclassical model, the higher kET for D-SSS-A/H2O as compared to DMSO can be attributed to a higher |V|. An analysis using this model and a dielectric continuum description for the solvent reorganization energy indicates that the electronic coupling values for D-SRR-A and for either solute in DMSO are very similar (see Table 1), whereas that for D-SSS-A in water is three times larger. It is important to note that many solvent/solute conformations are possible and thermally sampled, so that the |V| in Table 1 should be considered a root mean square value (see reference 10). These experimental results in water substantiate earlier theoretical predictions that water molecules located in the vicinity of donor and acceptor units can mediate the electronic coupling; i.e., electron transfer can proceed by tunneling through water molecule(s).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge financial support from the US National Science Foundation (CHE-0415457 and CHE-0718755). This research was supported by the NIH/NIGMS (GM067866) to C.E.S. Mr. Chris Morgan contributed to this work in its early stages.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Synthesis of D-SSS-A, D-SRR-A and acceptor only (control) molecules; table of kET for D-SSS-A and D-SRR-A in different solvents; and details of continuum model calculation. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Beratan DN, Onuchic JN. In: Protein Electron Transfer. Bendall DS, editor. BIOS Scientific Publishers Ltd.; Oxford: 1996. p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg JM, Stryer L, Tymoczko JL. Biochemistry. 5th Ed. Freeman; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Page CC, Moser CC, Chen X, Dutton PL. Nature. 1999;402:47. doi: 10.1038/46972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin J, Balabin IA, Beratan DN. Science. 2005;310:1311. doi: 10.1126/science.1118316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Balabin IA, Beratan DN, Skourtis SS. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;201:158102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.158102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Migliore A, Corni S, Felice RD, Molinari E. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:23796. doi: 10.1021/jp064690q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyashita O, Okamura MY, Onuchic JN. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:3558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409600102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wenger OS, Leigh RM, Villahermosa HB, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Science. 2005;307:99. doi: 10.1126/science.1103818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponce HB, Gray HB, Winkler JR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:8187. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The distances are center to center distances between the pyrene and dimethylaniline group found by molecular mechanics minimization of the molecular geometries in vacuo.

- 10.Zimmt MB, Waldeck DH. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003;107:3580. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Read I, Napper A, Kaplan R, Zimmt MB, Waldeck DH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:10976. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar K, Kurnikov I, Beratan DN, Waldeck DH, Zimmt MB. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998;102:5529. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Troisi A, Ratner MA, Zimmt MB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:2215. doi: 10.1021/ja038905a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levins CG, Schafmeister CE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4702. doi: 10.1021/ja0293958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nadeau JM, Liu M, Waldeck DH, Zimmt MB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:15973. doi: 10.1021/ja0372917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galoppini E, Fox MA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:2299. [Google Scholar]

- 17.The pKa of the dimethylaniline is 5.1. Around pH 7 100% of the molecule will be free amine whereas at pH 4.5 only 20% of the molecules will contain free amine group in the dimethylamine donor unit.

- 18.Marcus RA, Sutin N. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;811:265. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bixon M, Jortner J. Adv. Chem. Phys. 1999;106:35. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu M, Chakrabarti S, Waldeck DH, Oliver AM, Paddon-Row MN. Chem. Phys. 2006;324:72. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chakrabarti S, Liu M, Waldeck DH, Oliver AM, Paddon-Row MN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:3247. doi: 10.1021/ja067266b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharp K, Honig B. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Chem. 1990;19:301. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.19.060190.001505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newton MD, Basilevsky MV, Rostov IV. Chem. Phys. 1998;232:201. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matyushov DV, Voth GA. J. Chem. Phys. 1999;111:3630. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Read I, Napper AM, Zimmt MB, Waldeck DH. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2000;104:9385. [Google Scholar]

- 26.The reorganization energies were calculated using a continuum model that considers the solute as an ellipsoidal cavity; see Chem. Phys. Lett, 1977, 49, 299-304 & JPC, 1986, 90, 3657-3668). The equation and the calculation are shown in the supporting information.

- 27.The thickness of an aromatic ring is approximately 3.4 Å. Thus the π-orbitals of each aromatic chromophore in the D-SSS-A molecule extend into the cleft by about 1.7 Å, leaving a 1.2 Å gap between the donor and the acceptor.

- 28.The molecular radii were estimated from volume increments given by Bondi A. J. Phys. Chem. 1964:68, 441.

- 29.Turro C, Chang CK, Leroi GE, Cukier RI, Nocera DG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:4013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cukier RI, Nocera DG. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1998;49:337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.49.1.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hodgkiss JM, Damrauer NH, Presse S, Rosenthal J, Nocera DG. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:18853. doi: 10.1021/jp056703q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.